1. Introduction

The evolution of wireless communication networks has substantially reduced power consumption and extended the communication range for technologies that can enable implementation in Internet of Things (IoT) applications. Among these technologies, Low Power Wide Area Network (LPWAN) technology has emerged as a key enabler of scalable communication networks over large distances with minimal energy consumption (EC) requirements. Within the category of LPWANs, the long-range (LoRa) communication technology and its associated protocol stack, known as LoRa Wide Area Network (LoRaWAN), have become broadly accepted as crucial drivers of energy-efficient wireless connectivity over long distances across diverse IoT use cases.

Industry reports confirm LoRa technology’s dominant role within the LPWAN segment. According to recent LPWAN market data, LoRa accounted for 41% of all LPWAN connections outside China by the end of 2023. At the beginning of 2024, LoRa continued to be the dominant LPWAN technology in these regions, maintaining a clear lead over alternative technologies [

1]. This LoRa technology market dominance is projected to continue at an estimated compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 17% until 2027 [

1,

2]. Together with Narrowband Internet of Things (NB-IoT), LoRa and LoRaWAN jointly represented 87% of global LPWAN connections in 2023, a figure that, according to [

3], is expected to remain around 86% by 2030. Also, connections driven by LoRa networks are forecast to exceed 3.5 billion by the end of 2030 [

3].

The strong momentum in the practical implementation of LoRa/LoRaWAN technology is further reflected in LoRa technology hardware deployment and market expansion. The global LoRa/LoRaWAN IoT market is projected to grow from USD 8.0 billion in 2024 to USD 32.7 billion by 2029, with a CAGR of 32.4% [

4]. Other forecasts suggest similar dynamics, estimating growth from USD 8.66 billion in 2024 to USD 370 billion by 2037, driven by a CAGR of 33.5% [

5]. Regional analyses confirm these trends, with North America projected to capture 40.1% of the global LoRa/LoRaWAN IoT market in 2024 and to remain the largest regional market in 2025 [

6]. Therefore, estimates of LoRa technology market expansion indicate that LoRa technology will be massively implemented in future IoT networks.

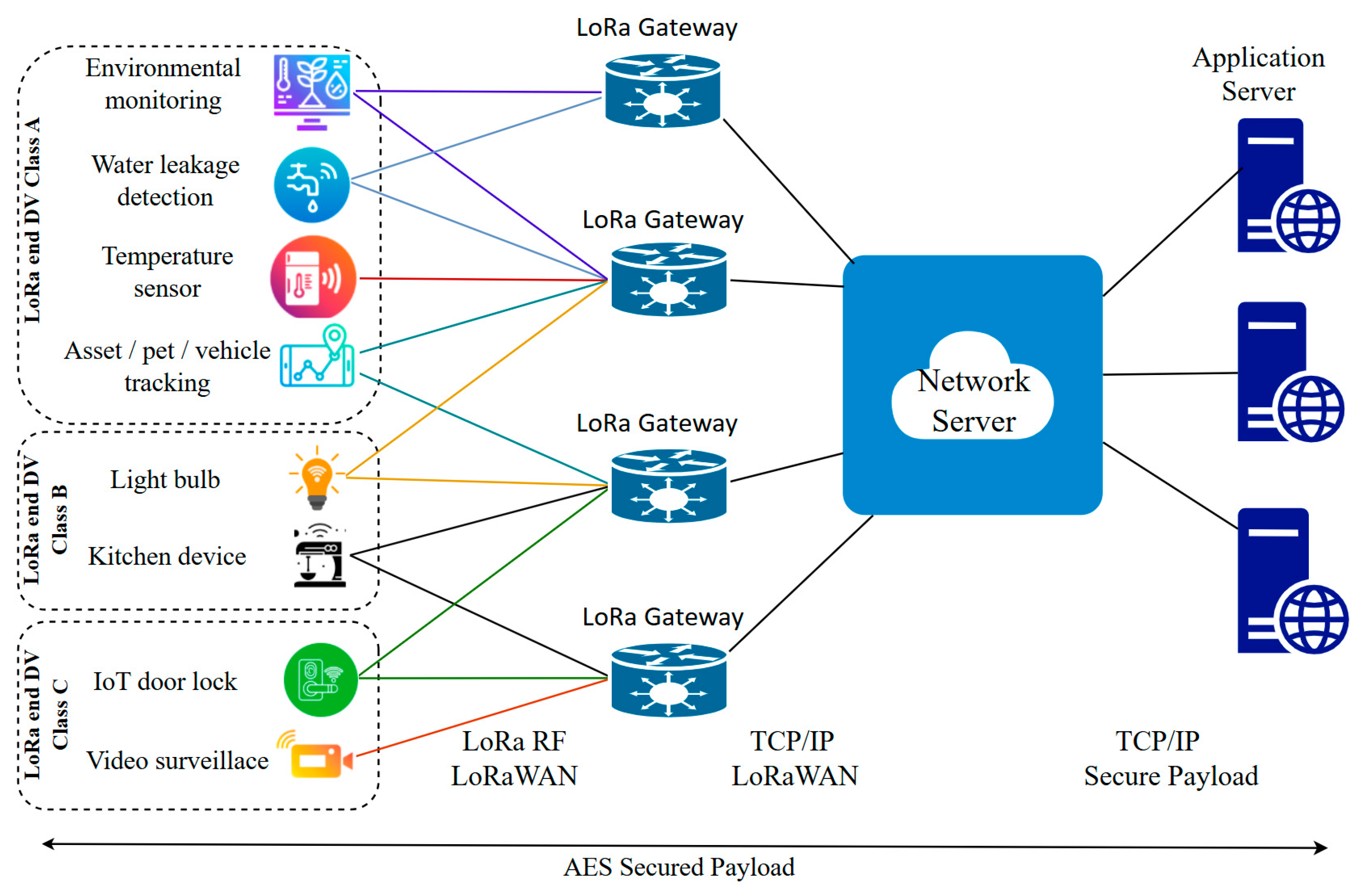

Figure 1 presents a typical LoRa network architecture, which consists of LoRa end devices (DVs) transmitting sensing data at low data rates to LoRa gateways (GWs) that act as access points. The GWs bridge the LoRa network with the wider wired network, by connecting network and application servers needed for ensuring a specific LoRa network IoT service. While the network server is a software component running on a server that manages the LoRa network and facilitates communication between end devices and applications (

Figure 1), the application server is another server-based software component responsible for processing and handling the application data. From a technical perspective, LoRa is a radio-frequency modulation technology for LPWANs based on Chirp Spread Spectrum (CSS) modulation [

7]. Its fundamental advantage lies in maintaining very low power consumption while enabling indoor wireless signal transmission [

8], and the long-range communication, which can be on average up to 5 km in urban areas and up to 15 km in rural environments [

9]. This is achieved through an architecture in which end devices remain predominantly in sleep mode, awakening only to transmit compact data packets at infrequent intervals, thereby achieving multi-year battery lifetimes under milliwatt-range instantaneous power consumption profiles [

7].

LoRaWAN, as the associated Medium Access Control (MAC) layer protocol, enables large-scale device deployments across various applications that include smart metering, industrial sensing, smart cities, precision agriculture, etc. Its operation in unlicensed industrial, scientific, and medical (ISM) frequency bands also enables indoor penetration, while its bidirectional communication capability makes it flexible and cost-effective for massive practical implementations. However, the EC of LoRa end devices (DVs) is strongly influenced by several transmission parameters, which include transmitted packet (payload) size (PS), spreading factor (SF), transmit (Tx) power, duty cycle (DC) period, retransmissions due to collisions and packet loss, and EC in the standby mode of operation [

10].

Understanding the relationship between the instantaneous EC of LoRa end DVs and key LoRa DV transmission parameters, such as SF, Tx power, and message PS, is essential for optimizing the energy efficiency (EE) of LoRa end DVs and LoRa networks. Multiple linear regression-based modeling can provide a systematic approach to quantifying the individual and combined effects of these parameters on LoRa end DV instantaneous EC, thus enabling the identification of LoRa DV transmission parameter configurations that balance performance with energy constraints. Given the energy-constrained nature of LoRa end DV, particularly in battery-powered and remote deployments, multiple linear regression-based models can be essential for identifying optimal LoRa end DV parameter configurations. Such configurations can contribute to minimizing EC without compromising communication reliability, which ultimately contributes to extending LoRa end DV lifespans and reduces maintenance costs. Also, LoRa end DV multiple linear regression EC models can be used in adaptive transmission schemes based on dynamically adjusting LoRa DV transmission parameters, which contributes to enhancing the energy sustainability and scalability of LoRa network deployments.

Thus, the objective of this paper is to analyze the EC characteristics of LoRa end DVs during a single transmission cycle, with a focus on identifying and quantifying the parameters that most significantly influence LoRa end DV EC. The main scientific contribution of this work lies in the development of multiple linear regression models that enable quantification of the impact of SF, PS, and Tx power on the instantaneous EC of LoRa DVs. These models provide a mathematical framework for projecting LoRa DV-level energy usage under various combinations of LoRa end DV transmission parameters and can be employed for EC planning and optimization of LoRaWAN-based IoT deployments.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents related work on modeling and analysis of the impact of transmission parameters on LoRa DVs EC.

Section 3 provides an overview of the LoRaWAN DV transmission parameters and DV classes.

Section 4 details the measured data collection and processing and describes the fundamentals of multiple linear regression modeling.

Section 5 presents the developed multiple linear regression models and the results of regression modeling analysis.

Section 6 discusses the obtained findings related to the impact of LoRa and DV transmission parameters on the EC, with an explanation of limitations related to the developed LoRa end DV EC regression models. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing the key conclusions while outlining potential directions for future research.

2. Related Work

LoRa technology and the LoRaWAN protocol, while designed for energy-efficient communications in IoT applications, are subject to significant variations in EC depending on the selection of LoRa end DVs transmission parameters such as SF, message PS, Tx power, coding rate (CR), operating frequency, and bandwidth. Different analytical, experimental, and optimization models related to quantifying the impact of these transmission parameters on LoRa end DVs EC have been proposed in the literature.

In ref. [

11], a general overview of LoRa technology was provided, including basic insights into how LoRa transmission parameters impact energy usage. In ref. [

12], the EC of the LoRa device was modeled by including uplink, downlink, and the first and second LoRa reception (Rx) windows. Analyses highlight that confirmed LoRa message acknowledgements (ACKs) substantially increase LoRa end DV EC, particularly when ACKs are transmitted through the second LoRa reception window at lower data rates.

In ref. [

12], the authors present one of the earliest analytical models that allow the characterization of periodic transmission of LoRaWAN Class A end DV lifetime, current consumption, and energy cost of data delivery. The analytical models were obtained, based on measurements that quantify the impact of relevant physical (PHY) and MAC layer LoRaWAN parameters and Bit Error Rate (BER) on energy performance.

In ref. [

13], the essential EC models for LoRaWAN sensor nodes were presented. Using both analytical derivations and experimental validation, the authors in ref. [

13] quantified the influence of Tx power, SF, CR, PS, and bandwidth on the overall LoRa end DV EC. Authors found that an increase in Tx power is more interesting in terms of consumed energy per useful bit than the increase in SF. However, a key finding of the study is that optimizing these transmission parameters is very important for reducing the EC of the LoRa sensor node. The work [

13] provided a foundation for subsequent LoRa end DV EC models, by showing that EC can be accurately predicted when transmission parameters are mapped to transmission duration and multiplied by the measured current draw of each LoRa ED operating state. Additionally, in ref. [

14], the LoRa end DV power consumption modeling is presented in a study that examines the relationship between SF, PS, CR, and EC in a LoRaWAN context.

In ref. [

15], a refined LoRa network EC model was proposed, incorporating network-level effects such as node density, collision probability, and retransmissions. This EC model provides a more realistic estimation of energy per delivered bit, particularly in dense deployments of LoRa end DVs with repeated transmissions. In refs. [

16,

17], a mathematical framework for evaluating LPWAN technologies with a focus on LoRaWAN was developed, optimizing SF, CR, and LoRa message PS under both acknowledged and unacknowledged transmission modes.

Experimental models also play a critical role in understanding the EE of LoRaWAN devices. Work in ref. [

18] analyzes EC of multiple LoRa prototyping boards and derived a power model linking transmission parameters (that include Tx power, data rate, and message PS) to measurable EC. The results showed significant differences across platforms, emphasizing the importance of hardware-level optimization. In ref. [

19], LoRa end DV battery lifetime was further evaluated by incorporating the microcontroller and sensor into the EC model. It was demonstrated that increasing BW shortens the ToA, enabling transmission of larger payloads with similar overall energy expenditure, which has a positive effect on LoRa DV lifetime. In addition, research presented in ref. [

20] proposes the LoRa end DV EC model that can be used to estimate the amount of energy each LoRa end DV consumes, with particular analyses on the impact on EC of LoRa end DV sensing interval and SF on battery lifetime.

Alongside analytical and experimental LoRa end DV EC models, the linear regression models have been extensively used for modeling the interdependence between the instantaneous power or EC and transmission parameters of wireless access network devices. In ref. [

21], authors based on obtained measurements developed linear power consumption models for mobile network base stations of different technology generations, which express a precise relationship between instantaneous power consumption and traffic load. Also, linear regression models have been developed based on performed continuous power consumption measurements in work [

22], for expressing the relationship between the base station’s instantaneous power consumption and specific transmission parameters such as base station Tx power.

However, despite the use of linear regression modeling of mobile network devices’ EC and a growing body of research focused on the energy performance of LoRa and LoRaWAN end DVs, a clear gap remains in the lack of formal statistical modeling of how the combination of specific LoRa DV transmission parameters influences instantaneous EC. Several studies, such as refs. [

13,

14,

20], have explored the impact of transmission parameters like SF, Tx power, and message PS on LoRa end DV energy usage, typically through empirical measurements or simulation-based evaluations. However, these works did not present a comprehensive multiple linear regression model that quantifies the combined and individual effects of these parameters within a unified statistical framework. As a result, there is limited quantitative insight into the magnitude and statistical significance of each parameter’s contribution to the EC variability of LoRa end DVs.

This study aims to address that gap by proposing and validating a set of multiple linear regression models, in which the instantaneous EC of LoRa end DVs is expressed as a function of key LoRa end DV transmission parameters, including SF, Tx power, and PS. Unlike prior works that analyze parameter influence in isolation or through heuristic estimation, in this work, multiple linear regression models are proposed to provide a systematic and interpretable expression for characterizing LoRa end DV trade-offs between a selected combination of transmission parameters and LoRa end DV energy-performance. The proposed models not only enable prediction of LoRa end DV EC for a specific combination of LoRa end DV transmission parameter configurations, but also contribute to the understanding of how these transmission parameters model the instantaneous EC of LoRa end DVs. Understanding these influences is essential for optimizing LoRa end DV operating autonomy and overall LoRa network EE.

3. LoRaWAN Transmission Parameters and End DV Classes

LoRaWAN is a low-power, wide-area networking protocol designed to enable long-range wireless communication between battery-powered LoRa end DVs and LoRa network infrastructure (GWs and servers) using the LoRa network PHY layer (

Figure 1).

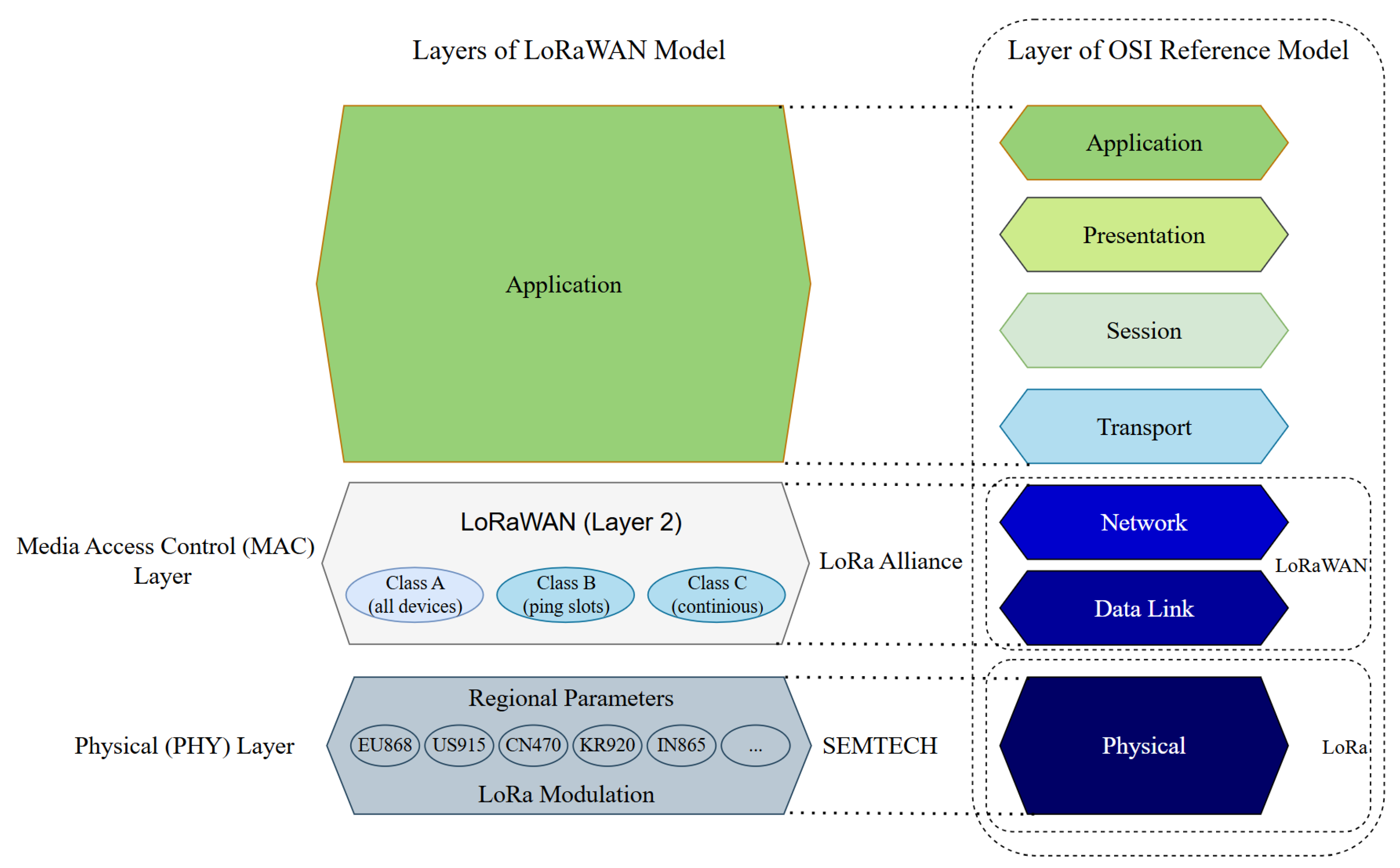

Figure 2 depicts the position of the LoRaWAN protocol in the Open System Interconnection (OSI) model. According to

Figure 2, LoRaWAN is a network protocol built on top of the LoRa technology, which operates at the second and third layers of the (OSI) reference model. Managed by the LoRa Alliance and standardized by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) under the recommendation ITU-T Y.4480 [

23], LoRaWAN supports features such as secure two-way communication, mobility support, encryption, and device authentication.

The main LoRaWAN transmission parameters that directly influence the instantaneous EC of LoRa end DVs are transmit (Tx) power, LoRa message packet (payload) size (PS), and the transmission spreading factor (SF). Together, these three parameters largely define the LoRa end DV radio’s active transmission and reception duration and output strength, which significantly impact LoRa end DV instantaneous EC and determine how quickly a battery-powered LoRa end DV depletes its energy resources. In addition, the LoRaWAN defines different classes of operating modes for LoRa end DVs. The different LoRaWAN end DV classes affect instantaneous EC primarily through how often the LoRaWAN end DV radio must wake up and listen for downlink messages. In subsequent sections, the main LoRa end DV transmission parameters and classes of operating modes dominantly impacting LoRa end DV EC are described.

3.1. LoRa Message Packet Size

LoRa networks are optimized for small and energy-efficient transmission of LoRa messages to maximize LoRa end DV battery duration and LoRa signal coverage. The LoRa message PS used in transmission is small, with a maximal PS of 250 bytes in case of LoRa end DV operating in not repeater-compatible mode, while for the case of LoRa end DV operating in repeater-compatible mode, the maximal PS is even smaller and can be up to 230 bytes [

24]. However, the maximal PS is additionally defined by the LoRa Alliance for different transmission parameters that include SF and BW. For example,

Table 1 presents regulatory LoRa Alliance maximal MAC layer PS and maximal application layer PS for different transmission parameter configurations of EU863–870 (EU868) and EU433 bands [

24]. The maximum MAC layer PS is derived from a limitation of the PHY layer (

Figure 2) and depends on the effective modulation rate used, taking into account a possible repeater encapsulation layer. The maximum application layer PS defines the maximum PS of the LoRa message set on the application layer (

Figure 2). According to

Table 1, LoRa end DV messages transmitted at higher SFs and at lower PHY bit data rates can have lower maximal PSs, and vice versa.

However, the PS directly influences the total data transmission duration, known as Time on Air (ToA). LoRa messages with larger PSs allow for more aggregated data transmission, but directly increase ToA and, consequently, device EC. The ToA or the LoRa DV message transmission time (T

message) is the time needed for message transmission by the LoRa end DV, and it is calculated as [

25]:

where T

preamble is the period of transmission of the preamble of a LoRa message, equal to

In relation (2), the n

preamble is the number of preambles, and T

s is the symbol duration expressed as

with SF representing the spreading factor level (from SF = 7 to SF = 12) and BW representing the LoRa channel bandwidth. The T

payload is the duration of transmission of the data payload of a LoRa DV message, expressed as

In relation (4), the PS represents the payload size, the CRC represents error correction cyclic redundancy check status (enabled = 1, disabled = 0), H represents LoRa message header type (implicit = 1, explicit = 0), DE represents low data rate optimization status (enabled = 1, disabled = 0), and CR represents coding rate value (1–4, default equal to 1).

Equations (1)–(4) show that higher PS in combination with increased SF, CR, and error correction CRC significantly extend ToA. This is desirable in reliability-oriented LoRa network deployments, while delay-sensitive or energy-constrained LoRa network deployments benefit from transmission of smaller payloads at lower SFs [

26]. Thus, PS directly affects how long the LoRa end DV must remain in transmit mode. The longer LoRa messages having higher PS require more bytes to be sent, which extends the transmission time and therefore increases total energy consumed by LoRa end DV, which can be expressed as

where P

Tx represents the Tx power of LoRa end DV. A longer ToA for the same Tx power leads to higher EC and increased spectrum occupancy, which also directly limits channel availability.

3.2. Overview of LoRa End DV Classes

An important characteristic of the LoRaWAN protocol is support for operation of different LoRa DV classes, known as LoRa DV Class A, B, and C (

Figure 2).

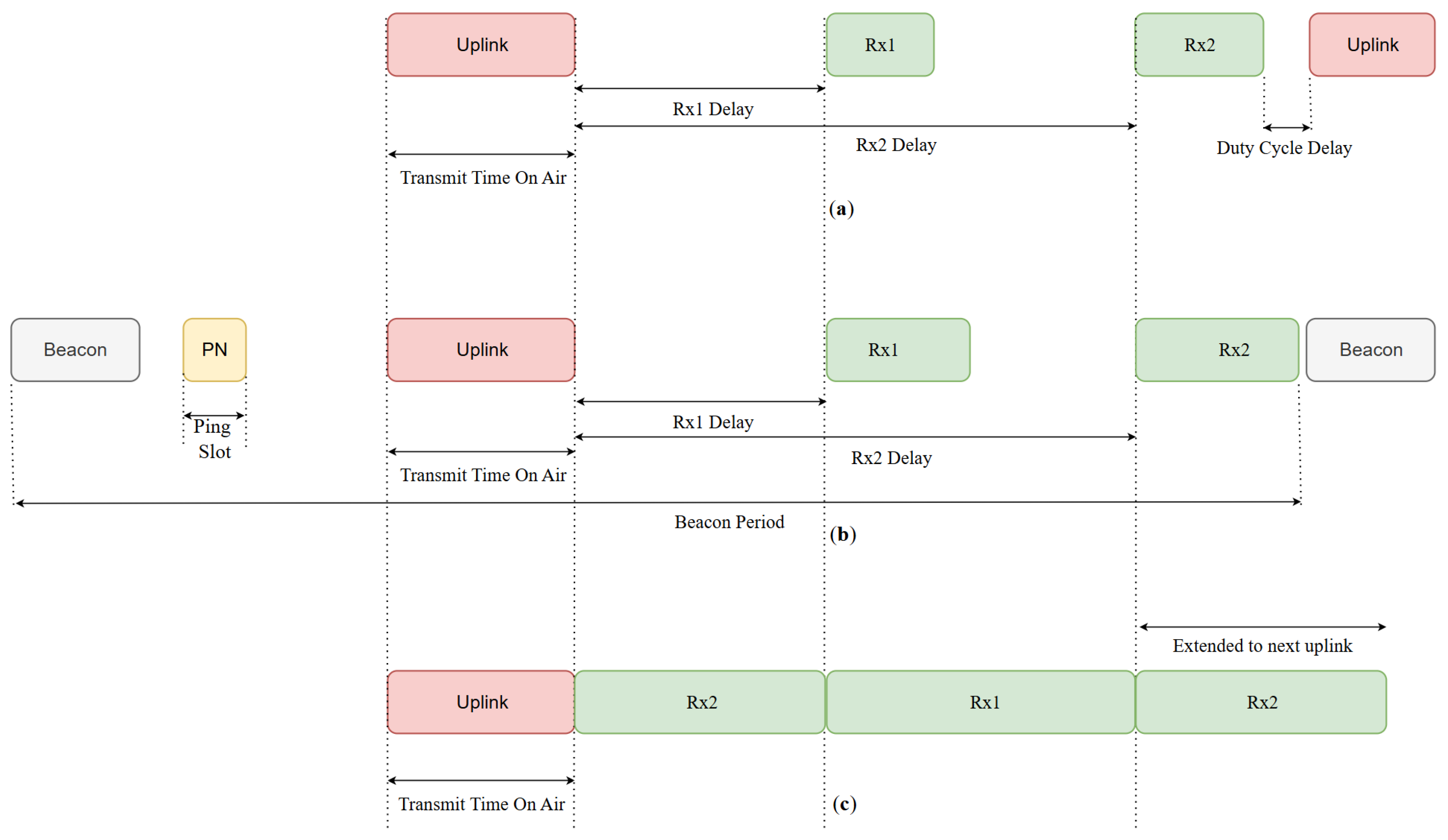

Figure 3 presents the operating principles during one transmission and reception cycle of these three LoRa end DV classes, where each class is optimized for different application scenarios. The LoRa end DV classes model decomposes the DVs operation into sleep and active operating phases, where the active part includes data transmission and reception, and the sleep state is characterized by minimal DV processing activity, which is aimed at LoRa DV energy savings. The LoRa end DV classes are designed to balance DV EE and data transmission latency requirements across a wide range of LoRa network applications.

3.2.1. Operating Principles of LoRa End DV Class A

The Class A LoRa end DV operating mode is mandated to be supported by default by all LoRa end DVs. It provides the highest EE among all LoRa end DV operating modes, since devices spend most of their operating time in sleep mode and only open short receive windows after performing an uplink transmission (

Figure 3a).

Communication is initiated by an uplink transmission, after which the two receive (Rx1 and Rx2) windows are sequentially opened. The duration of transmission in the uplink communication window is set by LoRa DV-specific transmission parameters that include SF, PS, and CR (Relations (1)–(4)). The LoRa end DV operating in Class A mode can send an uplink message at any time [

27].

When a network server wants to communicate with a LoRa end DV (

Figure 1), it has to wait for the end DV to open receive (Rx) windows (Rx1 and Rx2); therefore, it has to wait for the end DV to establish an uplink communication first (

Figure 3). If no downlink message is received within the Rx1 window, subsequently, a second receive window Rx2, is opened (

Figure 3a). The delay between uplink and receive (Rx1 and Rx2) windows is typically one second and two seconds, although this parameter can be programmable.

The length of the Rx1 and Rx2 windows must be at least as long as the time necessary for the LoRa end DV radio receiver to accurately identify the preamble of the downlink message. If the LoRa end DV detects the preamble of the downlink message, the receiver stays activated until the whole downlink message is demodulated; otherwise, the LoRa end DV transceiver returns to sleep state immediately (

Figure 3a) [

10]. If a downlink message is successfully received during the Rx1 window, the second Rx2 window is not activated, thereby reducing unnecessary EC. If LoRa end DV does not receive messages during these two Rx1 and Rx2 windows, the next downlink message can only be scheduled after the next LoRa end DV uplink transmission [

27].

In case of no expectation of receiving any downlink packets, the LoRa end DV will sequentially open both Rx windows, but only briefly enough to detect the lack of presence of a preamble of a downlink message (

Figure 3a). The shortest duration of Rx windows is 5.1 ms when operating at SF7. The maximum duration of the Rx windows is 164 ms when LoRa end DV operates at SF12. Conversely, if a downlink message is incoming to the LoRa end DV operating at SF7, the message demodulation process during the Rx window will take under 100 ms, and if LoRa end DV operates at SF12, the Rx window will last more than two seconds [

10].

Therefore, end LoRa Class A DVs remain predominantly in sleep mode (

Figure 3a), and only activate the transceiver when (i) sensor readings change or (ii) a predefined reporting interval expires. This operating mode minimizes LoRa end DV EC by ensuring that the radio unit remains inactive for the majority of the LoRa end DV lifetime. Since downlink communication from the network is only possible immediately following an uplink (

Figure 3a), this introduces latency but maximizes battery lifetime [

28]. Some of the possible use cases of Class A end DVs in practical implementations are smart metering (water, gas, electricity, etc.), environmental monitoring (air quality, temperature, humidity, etc.), agriculture sensing (soil moisture, irrigation control, etc.), asset/animal tracking, parking sensors, waste management (smart bins), etc.

3.2.2. Operating Principles of LoRa End DV Class B and Class C

The Class B is LoRa end DV operating mode in which LoRa end DVs synchronize with the network through reception of beacons sent periodically over LoRa GWs (

Figure 3b). Synchronizing with the network enables LoRa end DVs to periodically open ping slots, which represent additionally scheduled Rx windows for data reception (

Figure 3b). This allows the LoRa network server to know when to send a downlink message, which results in more frequent downlink communication at the cost of a higher EC of the LoRa end DV. While this mechanism decreases downlink latency in LoRa networks, it results in increased EC of LoRa end DVs compared to Class A, making it suitable for applications where moderate latency and extended battery life must be balanced [

28]. Some of the possible use cases of Class B end DVs in practical implementations are utility metering (of electrical, water, gas, etc.), management of street lighting, industrial monitoring, etc.

Class C is LoRa end DV operating mode in which LoRa end DVs keep their receivers continuously active, enabling immediate downlink access (

Figure 3c). Similar to the Class A operating mode, Class C has two Rx windows, with the Rx2 receive window that is continuously opened, after a short Rx2 window, and then the Rx1 window are sequentially opened (

Figure 3c). This enables LoRa Class C DVs to receive downlink messages at any time. While this minimizes data transmission latency, which is the lowest among LoRa end DV classes, it requires consumption of significantly more energy for DV operation and is generally used in applications where constant availability among communicating DVs is critical. The Cass C operating mode is especially advantageous for latency-sensitive applications such as industrial automation or critical infrastructure monitoring. However, the continuous activity of the transceiver significantly increases LoRa end DV power consumption, thereby limiting the applicability of Class C operating mode to LoRa end DVs with a reliable and constant power supply [

28]. Some of the possible use cases of Class C end DVs in practical implementations are smart grid equipment (transformer monitoring, grid control,…), industrial machines needing rapid commands, remote-controlled actuators (valves, pumps,…), safety and alarm systems, smart building control, etc.

This classification of LoRa end DVs operating modes allows LoRaWAN to adapt to different low-power use cases, such as occasional remote sensing applications, and demanding applications that require frequent or low-latency communication [

13]. Since Class B and Class C LoRa end DVs can also operate in Class A mode, and Class A DVs dominate in practical deployments due to their optimized low-power behavior, linear regression modeling analyses have been further performed in this work for Class A LoRa end DVs. Also, sending downlink messages in many practical LoRa network applications is used rarely and only when needed, since they are energy costly. This additionally motivates performing multiple linear regression modeling analyses of EC for only Class A LoRa end DVs, whose operation is characterized by the least frequent transmission of LoRa downlink messages in comparison with other LoRa end DV operating modes.

4. Measured Data Collection and Regression Modeling

The regression analysis in this study was performed with the aim of modeling the impact of varying transmission parameter configurations on EC of LoRaWAN end DVs. In this paper, the EC of LoRaWAN devices was analyzed, specifically during the period of one cycle of data transmission and reception. The focus is on analyzing the impact on LoRa DV EC of the SF, Tx power, and LoRa message PS, as key LoRa transmission parameters impacting EC. To perform such analyses, the precise and comprehensive measurements of instantaneous electric current for LoRa end DV operating with different combinations of transmission parameters have been performed. The obtained measurement results have been used for further multiple linear regression modeling and analyses of LoRa end DV EC.

4.1. Measurements and Data Collection

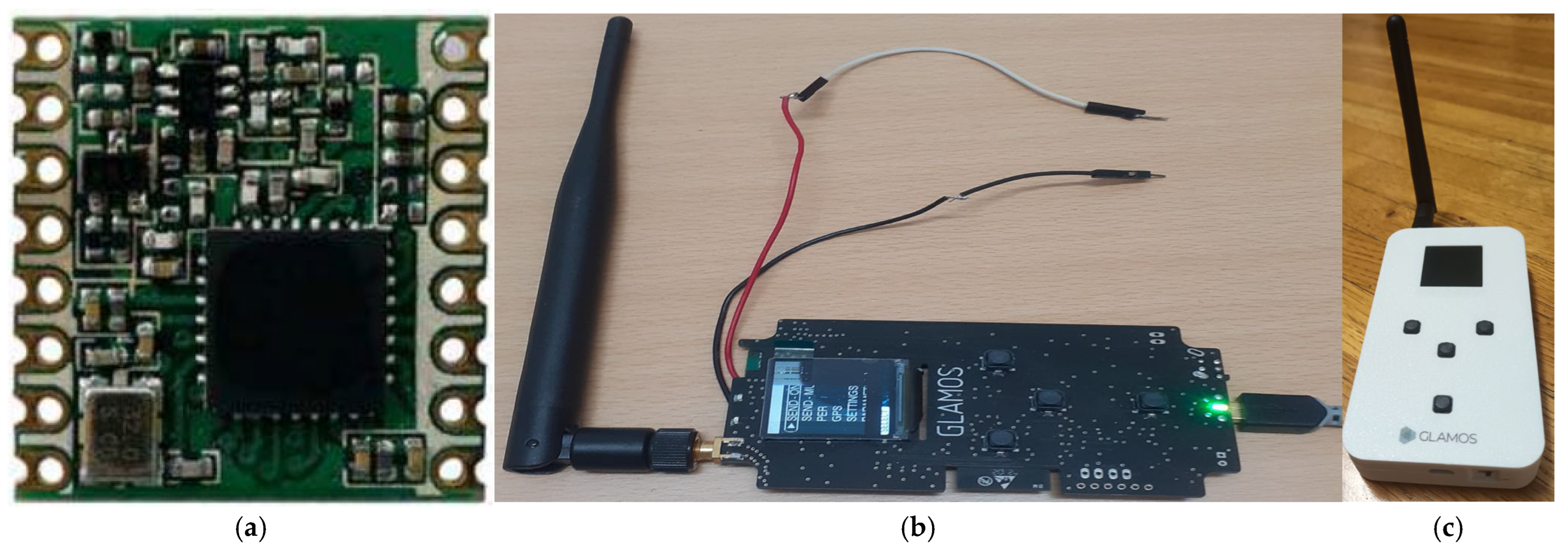

The comprehensive electric current measurements were conducted on a LoRaWAN end DV, realized with HOPERF Microelectronics RFM95W transceiver module having omnidirectional antenna [

29].

Figure 4a presents the transceiver module RFM95W of the LoRa end DV used in analyses, and

Figure 4b presents the analyzed LoRa end DV with antenna and configuration display. The technical specification of the LoRa end DV RFM95W transceiver module used in the analyses is presented in

Table 2 [

29].

The objective of the performed measurements was to quantify LoRa end DV variations in instantaneous electric current during one transmission and reception cycle of a LoRa message, which includes both active and sleep (standby) LoRa end DV operating states. Precise measurements were conducted for combinations of different LoRa end DV transmission parameters, and such combinatory were based on variable transmission parameters such as SFs, Tx powers, and PSs, and fixed transmission parameters related to transmission frequency, CR, and channel BW.

Table 3 presents all transmission parameters used in the measurements performed for different combinations of stated fixed and variable LoRa end DV transmission parameters. Each combination of transmission parameters represents one measuring set (MS). The variable transmission parameters, such as the level of SF, were varied from SF7 to SF12, the level of Tx power was changed to be 2 dBm, 10 dBm, and 20 dBm, and PSs were changed from 1 B to 200 B (

Table 3). In the analyses, the LoRa end DV operated with fixed channel BW, CR, and frequency equal to 125 kHz, 4/5, and 867.1 MHz, respectively.

Measurement results for a total of 69 MSs (combinations of transmission parameters) were collected for further regression analyses. Each of 69 MSs is compliant with the LoRa Alliance regulations, which are related to restrictions on PS for transmission with a specific SF, are presented in

Table 1. Therefore, the measurement results of each MS, characterized by the specific configuration of LoRa end DV transmission parameters in each MS, formed the experimental dataset for subsequent regression analyses.

The LoRa end DV used in analyses operated in Class A operating mode with unconfirmed messaging, which means that no LoRa acknowledgements and downlink messages were received during the measurements.

4.2. Measurement Setup

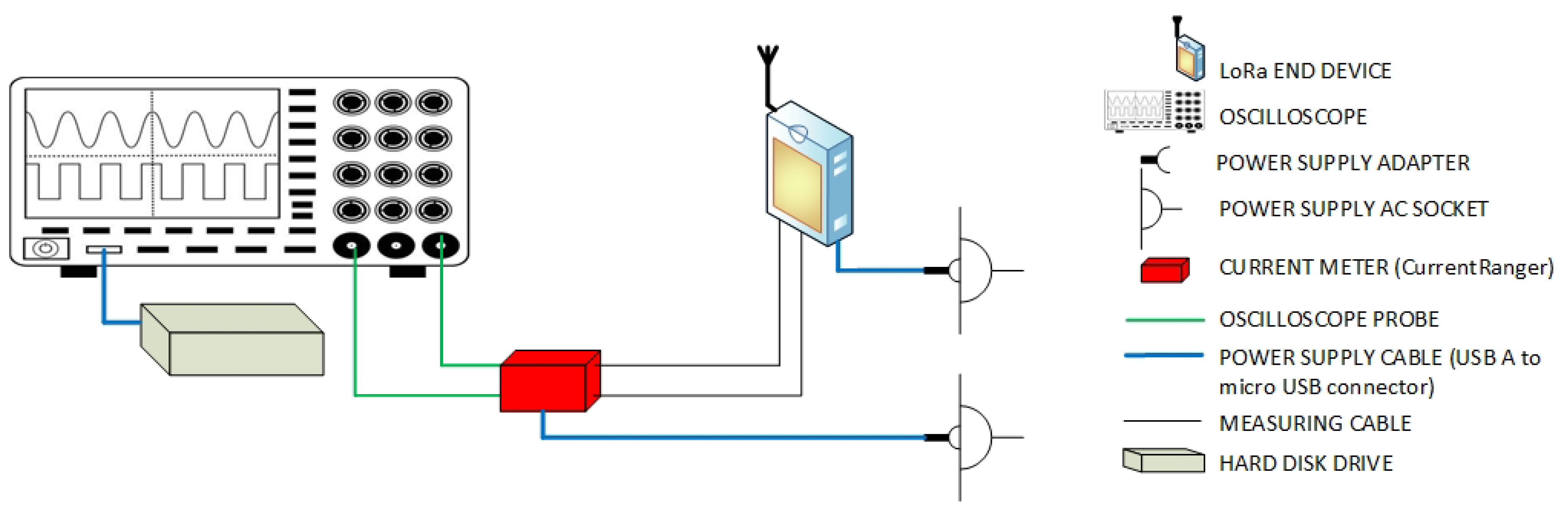

In

Figure 5, the measurement setup used for performing instantaneous electric current measurements during LoRa end DV operation at different transmission parameter combinations has been presented.

Table 4 presents an overview of devices and measurement configuration parameters used in measurements. The measuring setup presented in

Figure 5 enables precise measurement of the LoRa end DV instantaneous electric current using an oscilloscope connected to the current measuring device, which is further connected to the LoRa end DV. The LoRa end DV has a direct current (DC) power supply obtained from the alternate current (AC)/DC adapter plugged in a wall socket, which ensures an AC power supply.

For precise measuring of LoRa end DV low electric currents, the special current measuring device (CurrentRanger) powered from the AC grid over an AC/DC adapter was used [

30] (

Table 4,

Figure 5). The CurrentRanger is a configurable auto-ranging high-sensitivity current meter. It is used in measurements since it enables high electric current measuring precision and capturing fast electric current transients that are characteristic for LoRa end DV operation (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Overview of measurement devices and parameters.

Table 4.

Overview of measurement devices and parameters.

| Device/Parameter | Type/Value |

|---|

| Oscilloscope type | Keysight Technologies DSO1052B (50 MHz bandwidth) [31,32] |

| Measurement sampling frequency | 1 Gsps |

| Measurement DC gain accuracy | 2 mV/div, ±4.0% full scale |

| Oscilloscope memory record length | 16 kpts |

| LoRa end DV motherboard | HOPERF Microelectronics RFM95W [29] |

| Current meter | CurrentRanger (auto ranging 1 mV output per nA/µA/mA) [30] |

| Power supply adapter | 220 V AC/6 V DC (max.) |

| Hard disk drive | HDD 1 TB |

The measurements were visualized in an oscilloscope, which is also used for transferring the measured electric current data to the hard disc drive for permanent storage (

Table 4,

Figure 5). The oscilloscope’s electric current sampling rate used in measurements was 1 Gsps (1 billion samples per second) of the input electric current signal. Such a signal sampling rate of every 1 ns enables accurate observation of high-speed signals and fast electric current transients up to 50 MHz. The oscilloscope used for measurement has a DC gain accuracy of 2 mV/div with ± 4.0% full scale tolerance. The measured electric current data samples taken from the oscilloscope memory record, having a length of 16 kpts are permanently stored in a hard disk drive of 1 TB capacity for further data processing and analysis in the comma-separated values (CSV) format.

4.3. Processing of Electric Current Measurements

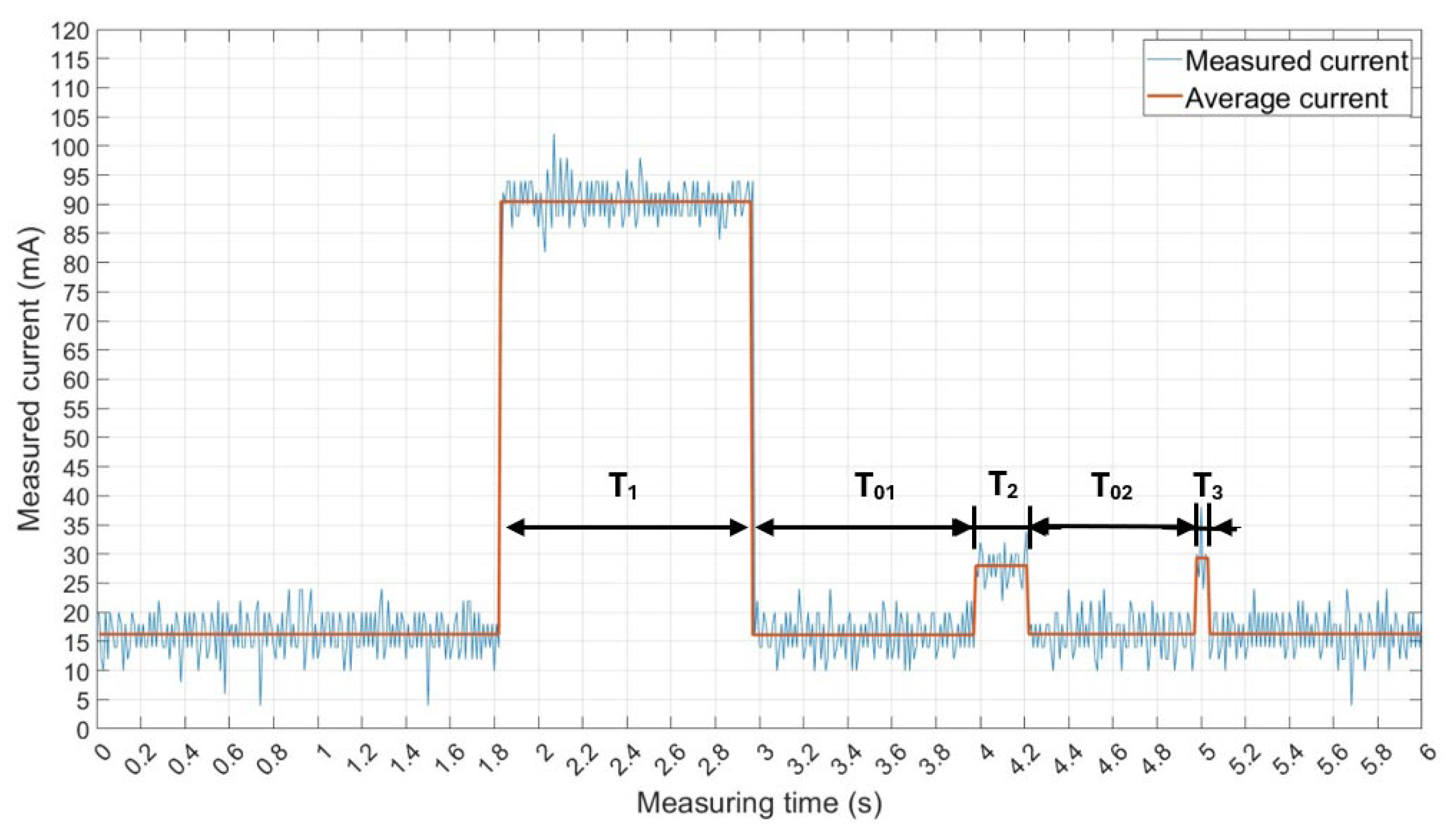

An example of the measured electric current trace for the MS9 is presented in

Figure 6, showing the instantaneous measured and averaged electric current values for one complete LoRa message transmission and reception cycle. Measurements of electric current were performed within the time period of one transmission and reception cycle lasting exactly 6 s (

Figure 6). The period of 6 s was selected for precise electric current measurements of LoRa end DV, due to the fact that even transmission and reception of the longest LoRa end DV message PSs at the highest SFs (SF12) can be performed in the interval lasting 6 s. Measurements of electric current presented in

Figure 6 reflect the behavior of one Tx and Rx cycle for the Class A LoRa end DV described in

Section 3.2.1.

To provide more precise insights into the measurement data for MS9,

Table 5 presents a detailed overview of the transmission parameters for MS9, with the time intervals and the values of the measured electric current across different Tx (uplink), Rx (downlink), and sleep (standby) state time intervals. An example provided in

Table 5 presents measuring results for MS9 with transmit parameters set to SF12, Tx = 20 dBm, PS = 1 B, CR = 4/5, BW = 125 kHz, and transmission frequency equal to 867.1 MHz (

Table 3).

According to

Table 5, the raw measurement data presented in

Figure 6 for MS9 were for each MS structured into time intervals with calculated mean, maximum, minimum, median, and standard deviation values of the measured electric current. The listed intervals capture the characteristic sleep (standby), uplink (Tx), and downlink (Rx) LoRa message transmission and reception pattern during one cycle of LoRa end DV communication (

Table 5). This pattern captured for a specific transmission parameter combination (MS) alternates between sleep (standby) phases, transmit bursts, followed by short reception periods (

Figure 6). This pattern reflects the characteristic duty cycle of LoRa end DV operating in Class A mode, in which extended periods of relative inactivity are periodically interrupted by short, but energy-intensive uplink transmissions and downlink receptions.

The sleep (standby) period summary row in

Table 5 represents aggregated statistics for all sleep (standby) operating intervals when the LoRa end DV does not transmit or receive. Although measured electric current levels in these phases are relatively low, their long duration means that they contribute to the overall LoRa end DV energy budget (

Table 5). In contrast,

Figure 6 shows that the period of the Tx window is different from the periods of Rx windows in one transmission and reception cycle, and it is characterized by much higher electric currents than those of sleep (standby) operating periods. This electric current in Tx and Rx periods represents the main drivers of LoRa end DV EC within the one communication cycle.

For all MSs, the shape of the measured current consumption pattern was the same as the one presented for the MS9 in

Figure 6. The measured electric current pattern for different MSs only differs in terms of measured electric current values for Tx and Rx windows and their durations. Those values are directly influenced by specific transmission parameter configuration, which is different for each one of the 69 MSs. Therefore, the presented structured electric current measurement breakdown highlights which LoRa end DV operating states are the most energy-demanding.

4.4. Energy Consumption Calculation

Based on the mean (average) measured electric current and precise knowledge of the time intervals’ duration characteristic for sleep (standby), Tx and Rx operating states of the LoRa end DV, calculation of LoRa end DV EC was performed within the time period of one LoRa message transmission and reception cycle. The duration of this time period is different for each MS, since every MS selected for analysis has different electric current measuring results for different combinations of LoRa end DV communication parameters. This results in different values of the overall EC of LoRa end DV for each combination of transmission parameter configuration.

From the measured data, the EC per one LoRa message transmission and reception cycle for each MS was calculated as the sum of the energy consumed during LoRa end DV operating in the Tx, Rx, and standby (sleep) periods (

Figure 6). The overall EC of LoRa end DV during one transmission and reception cycle for each MS was computed using the following relations:

where

is the measured supply voltage equal to 3.7 V (

Table 2), the

and

(i = 1, 2, 3) are the average electric current and precise durations of the i-th Tx or Rx period (window), respectively (

Figure 6). The

and

parameters represent the values of average electric current and precise duration of sleep (standby) intervals, respectively.

This formulation of LoRa and DV EC calculation ensures that all relevant operational states are represented in the calculation, providing a precise calculation of LoRa end DV EC for one LoRa message transmission and reception cycle. As an example,

Table 6 presents Lora end DV EC for some characteristic MSs obtained for different LoRa end DV transmission parameter combinations. The results presented for EC further illustrate how variations in Tx power, PS, and SF can affect the total EC for one LoRa message transmission and reception cycle.

4.5. Formulation of Regression Modeling

The structured dataset obtained based on comprehensive electric current measurements served as the basis for regression analyses, in which a total of 14 different multiple linear regression models were developed. Each multiple linear regression model is formulated to quantify the combined influence of two different transmission parameters, while keeping the third and remaining transmission parameters fixed. The general multiple linear regression model is expressed as:

where

represents the dependent variable, which is the LoRa end DV EC during one LoRa message transmission and reception cycle,

and

are the independent variables (transmission parameters),

is the intercept representing the expected value of y when all predictors are zero,

,

, etc., are the coefficients (parameters) representing the relationship between one or multiple independent variables (transmission parameters) and the dependent variable (EC). In relation (8),

and

quantify individual effects (slope) of variables (transmission parameters), while

(and higher-order terms) capture interaction or nonlinear effects of variables (transmission parameters) in a regression model, and

is the error term (residuals), which represents the variability in y that is not encompassed by the independent variables.

For cases requiring polynomial regression model representation, polynomial multiple linear regression models were developed in the standard form expressed as

where coefficients of nonlinear polynomial terms (e.g.,

) capture curvature in relationships and coefficients of interaction terms (e.g.,

) capture how predictors jointly influence the response. This enables a more accurate representation of real LoRa end DV EC behavior.

Proposed multiple linear regression models have been evaluated in terms of regression model accuracy (goodness of fit) and their predictive strength, by means of the key statistical parameters that include the F-statistics, the Prob (F-statistics), the coefficient R2, and the adjusted R2 coefficient. The F-statistic in regression analyses is a goodness-of-fit measure (statistics) that indicates whether the regression model provides a better fit to the data than a model that contains no independent variables. In essence, it tests if the regression model as a whole is useful.

The Prob(F-statistic), also called the p-value, is the probability of observing an F-statistic as large as (or larger than) the one computed from the sample under the null hypothesis, that all regression coefficients except the intercept are equal to zero. It measures the probability that the regression model provides no better explanatory power than a null model with no predictors (the intercept-only model). A smaller value of Prob(F-statistic) (lass < 0.05) indicates that the model fits the data significantly better than a null model. Also, p-values and values of standard errors (SEs) for estimated individual regression coefficients ( are calculated and presented in the analyses. The SE is the average distance between observed (actual) data points and the values predicted by the regression model. The p-value is the probability of observing results (or more extreme results) if the independent variable actually had no effect (the null hypothesis). In multiple linear regression modeling, the Ses measure prediction accuracy (smaller is better), while p-values indicate if a predictor’s effect is statistically significant (a small p < 0.05 means significant).

R-squared (R2), also known as the coefficient of determination, is a statistical measure that indicates how much of the variation in the dependent variable can be determined by the independent variables. For example, the R2 of 0.9 indicates that 90% of the variance is determined by the regression model, while the remaining 10% is attributed to error.

Adjusted R2 is a modified version of R2 that has been adjusted for the number of predictors in the regression model. The adjusted R2 metric penalizes inclusion of new variables in the model and gives a more reliable and conservative measure for comparing the goodness of fit. This provides a more accurate measure of fit for multiple regression models by accounting for the addition of irrelevant variables.

5. Results of Regression Modelling

The developed multiple linear regression models have been presented in this section. They provide mathematical expressions on how different combinations of LoRa end DV transmission parameters that include SF, Tx power, and LoRa message PS affect LoRa end DV instantaneous EC during one cycle of LoRa message uplink transmission and downlink reception. More specifically, for every developed multiple linear regression model, the dependent variable (EC) is expressed with two independent variables (transmission parameters) for the remaining fixed transmission parameters. Also, the goodness of fit statistical analyses have been presented for every developed multiple linear regression model, using standardized statistical parameters that include the F-statistic, the Prob (F-statistic), the coefficient R2, and the adjusted R2 coefficient.

The multiple linear regression models have been developed using Statsmodels and Scikit-learn open-source Python version 3.12.3. statistical modeling library. These libraries enable classical statistical analyses, including linear regression, generalized linear models, and produce p-values, confidence intervals, F-tests, etc. for developed regression models.

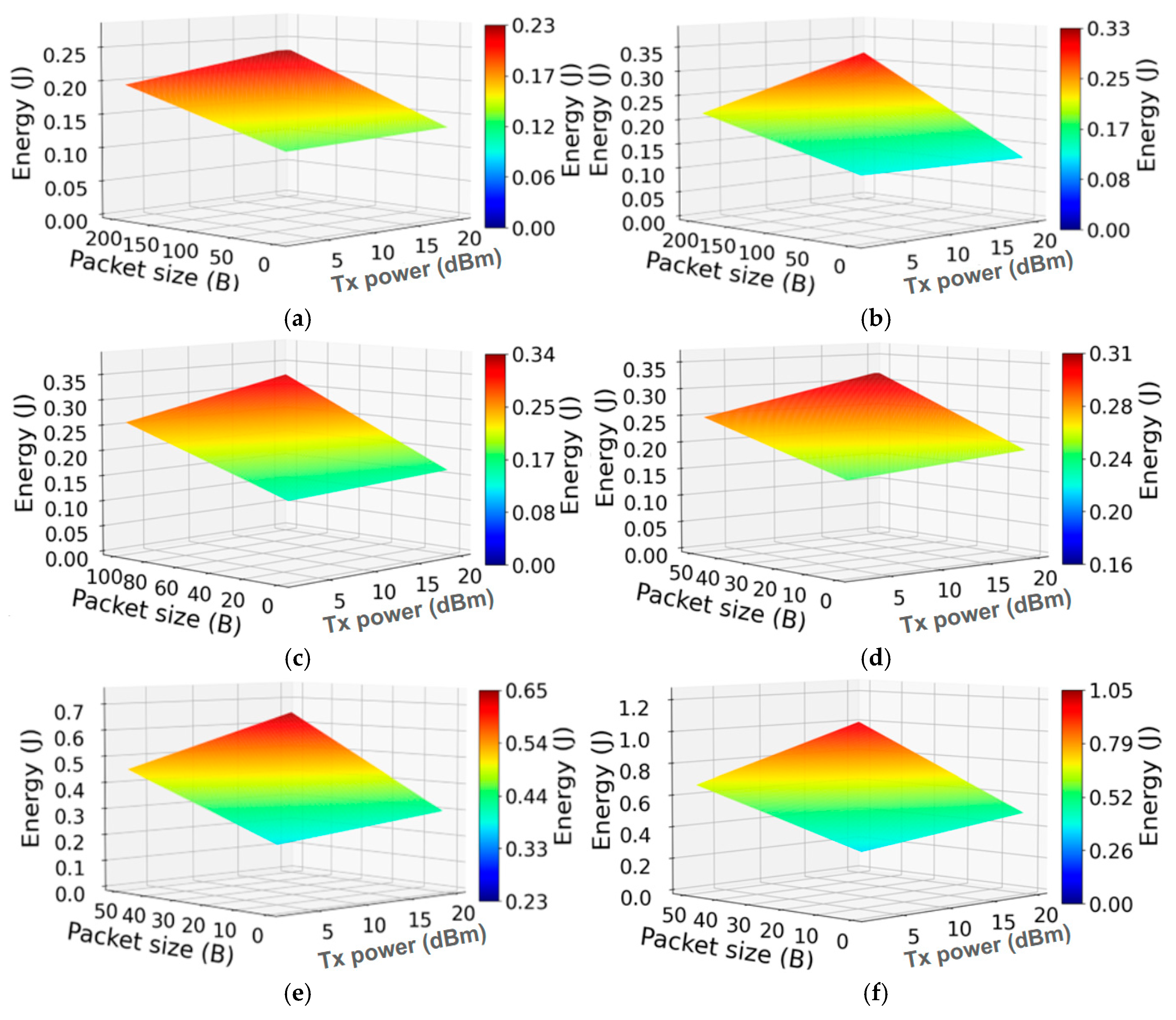

Mathematical formulation of multiple linear regression models was visualized in three-dimensional (3D) plots, presenting the EC on the z-axis and two variable transmission parameters on the x- and y-axes of the 3D plots. The 3D visualizations of developed multiple linear regression models enable the illustration of interactions between the main transmission parameters influencing LoRa end DV EC, namely, Tx power, PS, and SF. For 3D visualizations, the Python Matplotlib version 3.9.0. library “mpl-toolkits.mplot3d” module was utilized. The module allowed for the creation of 3D scatter plots and surface plots, which enable visualization of interactions between Tx power, SF, PS, and LoRa end DV EC. Thus, the 3D visualization of regression models is presented in the form of regression surfaces generated through curve fitting of the measured data, which allows a detailed comparison between empirical results and model predictions.

In addition, the EC presented on the z-axis is color-coded in the 3D visualization of linear regression models. This color-coding is performed using Matplotlib color maps and normalization techniques. This color-coding enhances the visualization of EC levels presented on z-axes of 3D plots, by providing an intuitive perception of how the combination of different transmission parameters impacts instantaneous LoRa end DV EC.

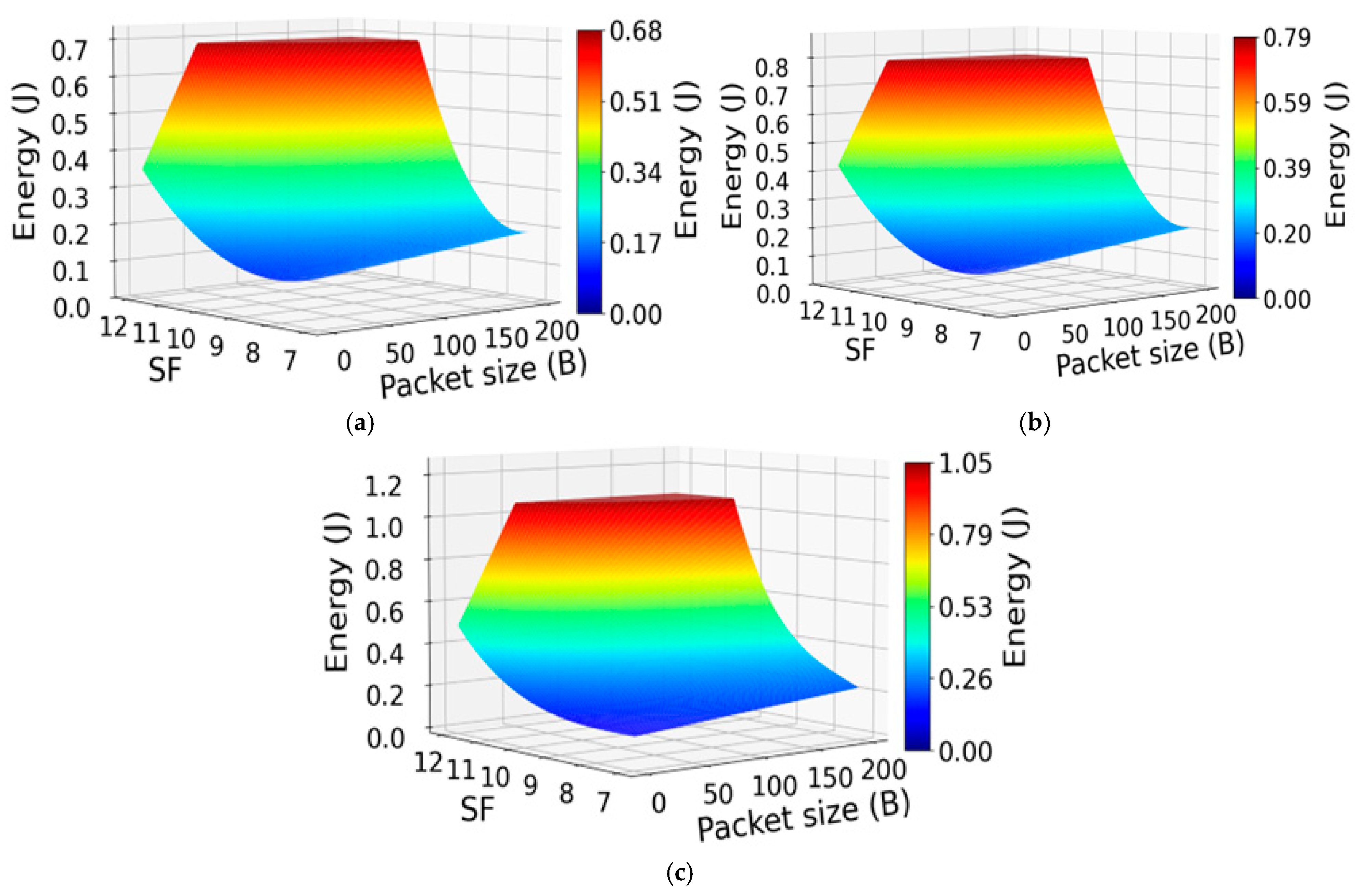

5.1. Regression Models for LoRa End DV Fixed Tx Power

The mathematical formulation of developed regression models (10)–(12) for LoRa end DV EC, and their goodness of fit statistical accuracy parameters are presented in

Table 7. Also,

p-values and values of standard errors (Ses) for estimated individual regression coefficients (

are presented in

Table 7, for a confidence interval of 95%. The regression models (10)–(12) presented in

Table 7 are developed for fixed Tx power levels of 2 dBm, 10 dBm, and 20 dBm, and variable values of SF (ranging from SF7 to SF12) and PS (ranging from 1 B to 200 B), where the SF and PS values are independent variables of the regression models. These models describe the effects of the joint impact of SF and PS on device EC for LoRa end DV transmitting at specific Tx power. The developed regression models incorporate both linear and nonlinear (polynomial or interaction) terms (relations (10)–(12)), thereby capturing not only the direct effects of SF and PS on LoRa end DV EC, but also their combined influence. They enable direct comparison of SF and PS x impacts on LoRa end DV EC during a single transmission cycle at fixed Tx power levels, highlighting the sensitivity of LoRa end DV performance relative to SF and PS transmission parameter selection.

The statistical goodness-of-fit results for the proposed regression models (10)–(12) presented in

Table 7 confirm the accuracy and robustness of the developed models. The coefficient of determination R

2 ranges from 0.979 to 0.990, while the adjusted R

2 spans from 0.972 to 0.987, reflecting a consistently high explanatory power. Similarly, the F-statistics are large, with probabilities well below

, which demonstrates strong statistical significance. Together, these values confirm that the regression surfaces reliably fit the empirical data. Also, the results of

p-values and standard errors (Ses) for the estimated regression model coefficients are presented in

Table 7. According to results presented in

Table 7, similar statistical significance for each of estimated regression model coefficients is obtained. The

p-value of “0.000” is not truly zero, but indicates high significance due to very low probabilities, suggesting that every independent variable (transmission parameter expressed as linear or nonlinear polynomial or interaction terms), strongly influences the outcome. Also, low values of SE indicate a small average distance between observed (actual) data points and the values predicted by the regression model, thus confirming the high regression model’s coefficients precision and low variability.

The 3D visualization of developed multiple linear regression models (10)–(12), indicating interdependence between LoRa end DV EC, SF, and PS, for fixed Tx power levels of 2 dBm, 10 dBm, and 20 dBm, is presented in

Figure 7a–c, respectively. More specifically, the regression models (10)–(12) presented in

Table 7 are visualized in 3D plots in

Figure 7a–c, respectively.

Figure 7 shows that EC increases when the SF level and PS increase. This is a consequence of the impact of both transmission parameters on the LoRa end DV transmission duration, which increases with an increase in one or both parameters. Thus, longer transmission durations caused by transmission at larger SFs, larger PSs, or both, consequently lead to greater energy usage, and vice versa.

In addition, regression models visualized in

Figure 7 show that for transmission at higher Tx power, the overall EC for the same combination of PS and SF parameters is increased (

Figure 7c), compared to transmissions at the same combination of SF and PS at lower Tx power levels (

Figure 7a,b). This is a consequence of the higher energy needed for the transmission of the wireless signal. Additionally, the developed regression models demonstrate that the growth of EC with increasing SF is nonlinear, having a significantly sharp rise of EC occurring for transmission at any Tx power levels between SF10 and SF12 (

Figure 7). This is consequently associated with the symbol durations that are longest at the highest SFs (SF10–SF12).

Figure 7 confirms that the increase in PSs amplifies this effect, since longer frames require proportionally more airtime for transmission, thereby magnifying the influence of both Tx power and SF. These findings confirm that PS acts as a critical scaling factor, intensifying the combined impact of transmission parameters on overall device EC.

From an energy perspective, the regression models visualized in

Figure 7 predict values of EC ranging approximately from 0.118 J to just over 1.048 J, for one LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle. This variation illustrates how SF and PS jointly shape the energy profile of the device, with higher values of both parameters contributing to steeper increases in LoRa end DV EC.

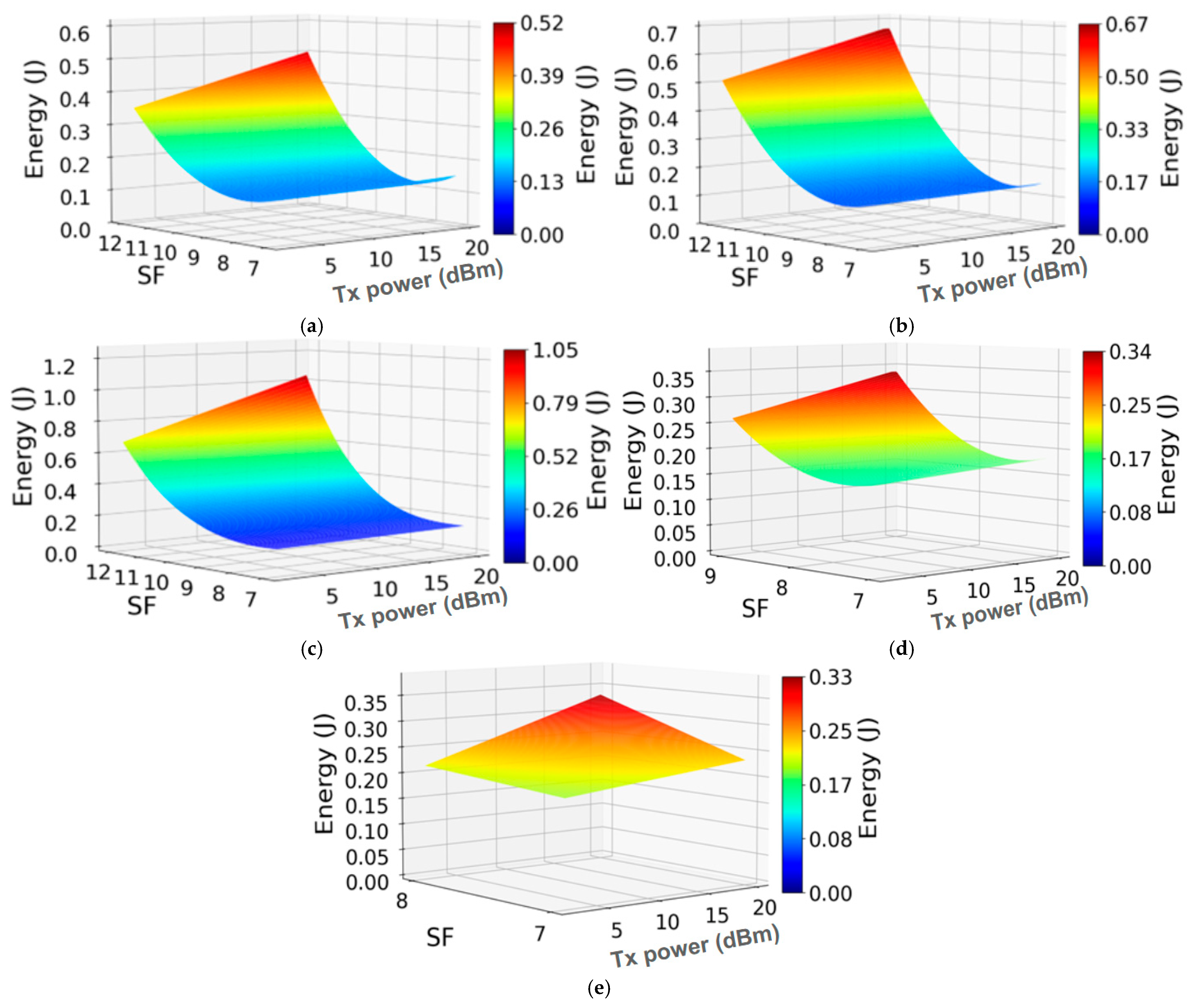

5.2. Regression Models for LoRa End DV Fixed PS

The mathematical formulation of developed regression models (13)–(17) for LoRa end DV EC and their goodness of fit statistical accuracy parameters are presented in

Table 8. Also,

Table 8 presents

p-values and standard error (SE) values in the case of the confidence interval of 95%, for estimated individual regression coefficients (

The regression models presented in

Table 8 are developed for fixed PSs of 1 B, 25 B, 50 B, 100 B, and 200 B, and variable values of SFs (ranging from SF7 to SF12) and Tx power levels (ranging from 2 dBm to 20 dBm), where the SF and Tx power levels are independent variables of the regression models. These models describe the effects of the joint impact of SF and Tx power on LoRa end DV EC for a specific LoRa message PS transmission and reception. The developed regression models incorporate both linear and nonlinear (polynomial or interaction) terms (relations (13)–(17)), thereby capturing not only the direct impacts of SF and Tx power on LoRa end DV energy, but also their combined influence. The developed regression models enable direct comparison of SF and Tx power impacts on EC for LoRa end DV during single-cycle transmission and reception of LoRa message of fixed PS, thus highlighting the sensitivity of LoRa end DV performance relative to SF and Tx power transmission parameter selection.

The goodness of fit statistical results presented in

Table 8 show that the minimum EC ranges from 0.118 J to 0.192 J, while the maximum values vary between 0.336 J and 1.048 J depending on PS. The average EC lies between 0.216 J and 0.361 J, with median values between 0.171 J and 0.237 J. From a statistical perspective, the values R

2 parameter range from 0.971 to 0.999, while the adjusted R

2 lies between 0.956 and 0.996, indicating excellent model fit. The F-statistic values are high, reflecting strong model significance, with corresponding probabilities ranging from 10

−11 to 10

−9 for most cases, except for results of PS equal to 200 B, where the weaker significance (

p = 2.62·10

−2) reflects slightly higher variability in the regression accuracy. Thus, developed regression models demonstrate high robustness and predictive accuracy across all tested configurations.

Also, results of

p-values and standard errors for the estimated regression model coefficients presented in

Table 8 show that Tx power is less statistically significant than SF, both as a standalone parameter or in the interaction terms. All interaction terms are statistically less significant than independent terms, suggesting that Tx power as a transmission parameter contributes moderately to the interaction effects compared to SF. Additionally, according to

Table 8, the model with PS equal to 200 B has all

p-values greater than 5%. This is a consequence of the lower number of observations (six in total) used in creating regression models. However, this regression model is valid because four additional regression models with the same variables were developed, having

p-values that confirm their accuracy and practical applicability. Additionally, besides SE values for

, a low value of SE for regression models

coefficients indicate a small average distance between observed (actual) data points and the values predicted by the regression model, thus confirming the high regression model’s

coefficients’ precision and low variability. Somewhat higher

coefficent SE values for some regression models indicate lower precision and higher variability in the estimation of the intercept, which does not have a significant impact since the intercept represents the estimated value when all predictors are zero, and this LoRa end DV transmission parameter combination is not practically relevant.

Figure 8a–e, present the 3D visualization of regression models that illustrate the interdependence between LoRa end DV EC, SF, and Tx power for five different PSs equal to 1 B, 25 B, 50 B, 100 B, and 200 B, respectively. More specifically, the regression models (13)–(17) presented in

Table 8 are visualized in 3D plots on

Figure 8a–c, respectively. Each surface visualization reflects how EC changes when two key transmission parameters (Tx power and SF) vary simultaneously for the transmission of a LoRa message of a specific PS.

The 3D visualization of regression models presented in

Figure 8 indicates that EC rises consistently with increasing Tx power and for transmission at higher SF values. Transmission at higher Tx power levels results in an emitted wireless signal with more energy, while larger SF values prolong the transmission duration (ToA) of the LoRa message. Both transmission parameters, individually and especially jointly, amplify the LoRa end DV overall energy demand needed for LoRa message transmission. This explains the reasons for the upward trends of the LoRa end DV EC, which can be observed in 3D visualizations for all regression model surfaces presented in

Figure 8.

The 3D visualization presented in

Figure 8 for the five regression models presented in

Table 8, further shows that larger PS values consistently yield higher EC for the same transmission parameters (Tx power –SF) combination. This is a consequence of the fact that the longer LoRa message PSs extend ToA, which requires more energy for transmission, while smaller LoRa message PS values, having shorter ToA, exhibit lower EC for identical transmission parameters.

Figure 8 shows that Tx power and SF both affect EC, but their combined impact grows with larger PS, highlighting the role of PS in long-term planning of LoRa end DV battery power supply. These results confirm that for transmission at fixed Tx power, PS and SF strongly influence the LoRaWAN DV single transmission and reception cycle EC, where the communication at smaller PSs and SFs produces lower overall energy demand.

5.3. Regression Models for LoRa End DV Fixed SF

The mathematical formulation of developed regression models (18)–(23) for LoRa end DV EC, and their goodness of fit statistical accuracy parameters are presented in

Table 9. Also,

p-values and values of standard errors for estimated individual regression coefficients (

are presented in

Table 9, for a confidence interval of 95%. The regression models (18)–(23) presented in

Table 9 are developed for fixed SFs equal to SF7, SF8, SF9, SF10, SF11, and SF12, and variable Tx power levels (ranging from 2 dBm to 20 dBm) and PSs (ranging from 1 B to 200 B), where the Tx power and PS values are independent variables of the regression models. These multiple linear regression models describe the effects of the joint impact of Tx power and PS on device EC for LoRa end DV transmitting at a specific SF. The developed regression models incorporate both linear and nonlinear (interaction) terms (relations (18)–(23)), thereby capturing not only the direct effects of Tx power and PS on LoRa end DV EC, but also their combined influence. They enable direct comparison of Tx power and PS impacts on LoRa end DV EC during a single transmission cycle at fixed SF level, highlighting the sensitivity of LoRa end DV performance relative to selection of Tx power and PS transmission parameters.

According to statistical goodness-of-fit results presented for multiple linear regression models presented in

Table 9, the minimum and maximum EC values range from 0.12 J to 1.05 J, with corresponding averages ranging between 0.15 J and 0.62 J. Median values follow a similar trend, confirming consistency in model predictions across different transmission parameter combinations. The F-statistic values span from −49.37 to 1586, reflecting variations in model strength depending on SF, while R

2 values remain within the range 0.93 to 0.999, and adjusted R

2 within 0.903 to 0.998. These high R

2 and adjusted R

2 values confirm the robustness and reliability of the regression models developed for transmission at different fixed SF values.

Also, results for

p-values and SEs for estimated regression model coefficients presented in

Table 9 show that for most of the regression models, the Tx power parameter as an individual parameter and as an interaction term is more statistically significant than SF. Also, low values of SE indicate a small average distance between observed (actual) data points and the values predicted by the regression model, thus confirming the high regression model’s coefficients precision and low variability.

Figure 9a–f, present a 3D visualization of the developed multiple linear regression models, indicating interdependence between LoRa end DV EC, Tx powers, and PSs for transmission at fixed SFs equal to SF7, SF8, SF9, SF10, SF11, and SF12, respectively. More specifically, the regression models (18)–(23) presented in

Table 9 are visualized in 3D plots in

Figure 9a–c, respectively. Each surface plot reflects how EC changes when two key transmission parameters (Tx power and PS) vary simultaneously for LoRa DV transmitting and receiving messages at a specific SF.

Figure 9 shows that the EC of the LoRa end DV increases with higher Tx power levels and larger LoRa message PSs, for each of the analyzed SF levels. This increase is a consequence of the fact that the transmission at higher Tx power results in higher wireless signal energy emitted by the LoRa DV, and larger PS results in longer data transmission (ToA). Thus, an increase in both parameters individually or in combination consequently contributes to the increase in LoRa device EC. Also, comparison of regression models presented in

Figure 9 indicates that for higher SF, overall EC for the same combination of PS and Tx power parameters increases. This is a consequence of the higher EC of the LoRa end DV, due to longer LoRa message ToA for transmissions at higher SFs. Therefore, the 14 developed regression models (10)–(23) provide not only an accurate modeling of LoRa end DV EC for different combinations of transmission parameters, but also give precise insights into the expected EC values under varying LoRaWAN transmission conditions, making them a valuable basis for both practical analysis and optimization.

6. Discussion

This section discusses the results of comparative analysis of the developed LoRa device EC multiple linear regression models, with respect to versatile combinations of transmission parameters that include different Tx powers, PSs, and SFs. Boxplots are used to visualize the distribution and variability of EC expressed in regression models (10)–(23), using a five-number summary that includes the EC maximum, third quartile (Q3), median, first quartile (Q1), minimum, and outliers of the analyzed EC regression models dataset. Also, comparison of results obtained for the mean (average) EC is presented in bar plots for different combinations of two LoRa end DV transmission parameters. Together, these visualizations provide detailed and aggregated analyses of LoRa end DV transmission parameter influence on EC, and enable gaining insights into the impact of different combinations of transmission parameters on LoRa end DV EC. Also, in this section, the limitations of the proposed multiple linear regression models have been discussed, with an explanation of how to use the developed multiple linear regression models in practical calculations of LoRa end DV EC during transmission periods longer than one transmit and receive cycle.

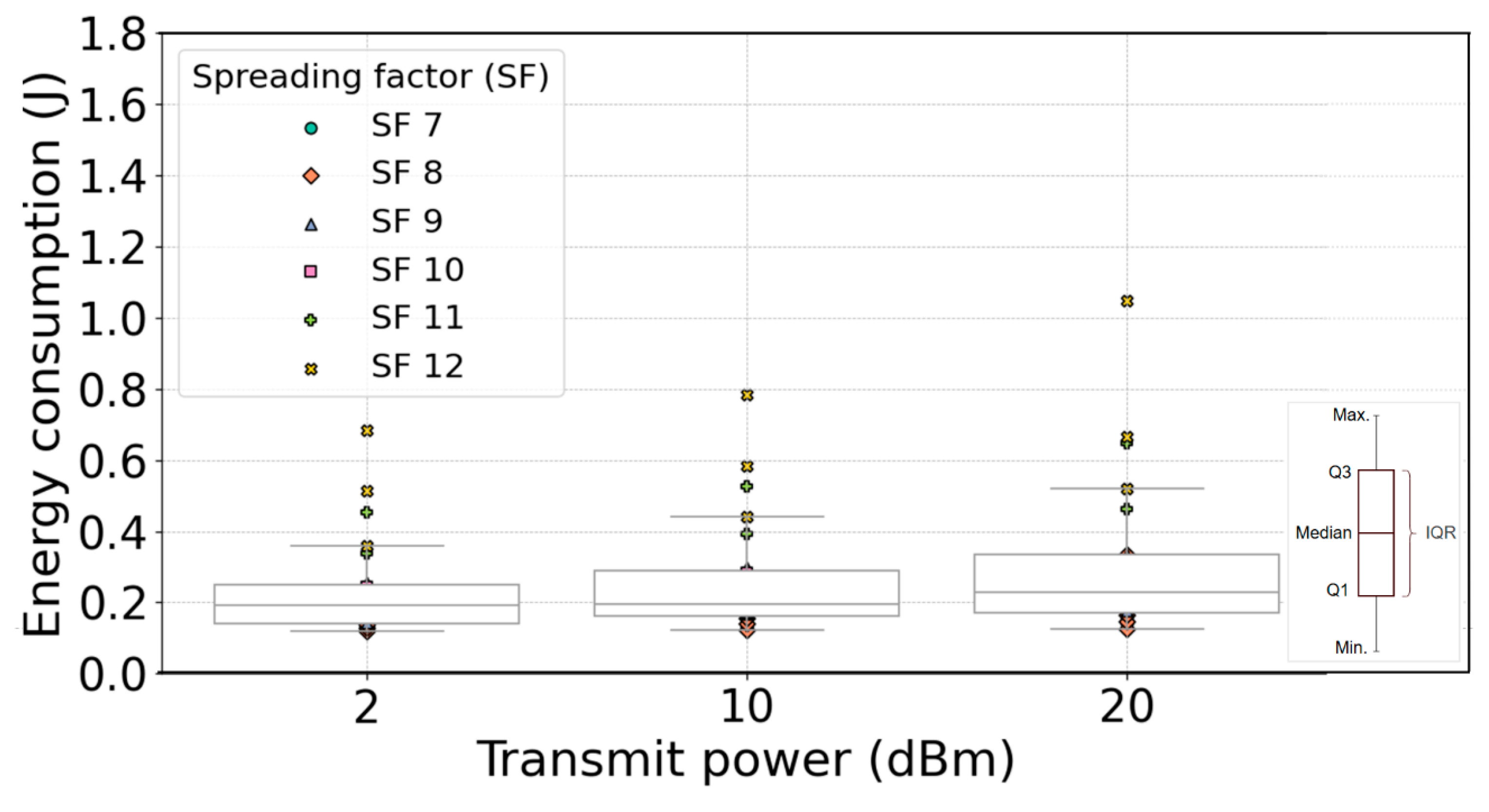

6.1. Numerical Analyses of EC Data Distribution for Regression Models with Fixed Tx Power

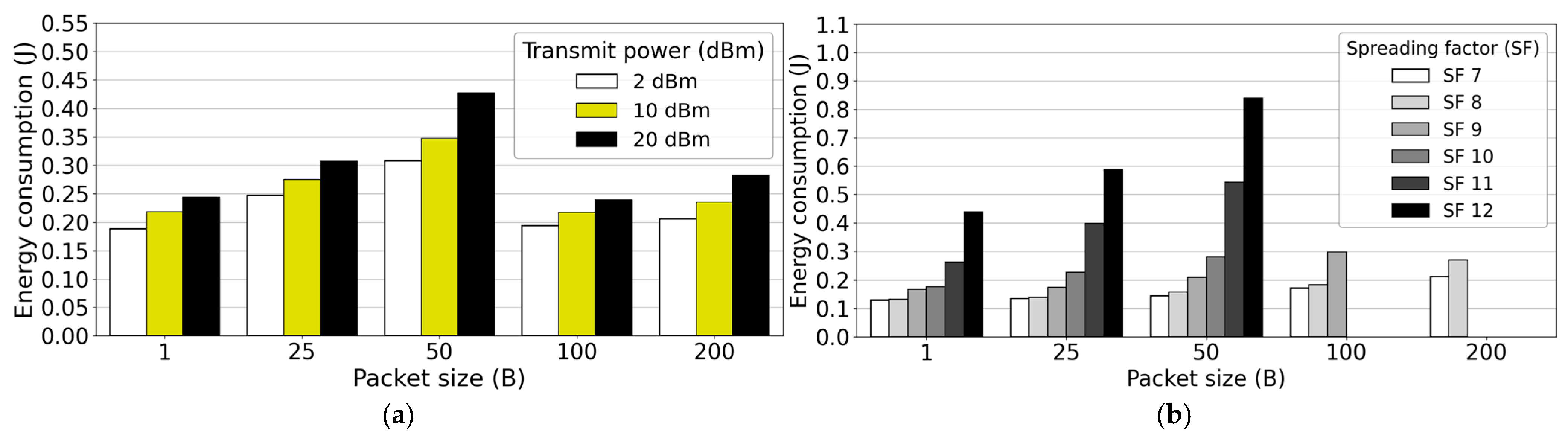

Figure 10 displays the boxplot visualization of the distribution of numerical data for regression models (10)–(12), expressing interdependence among the LoRa end DV EC and Tx power levels for different SFs and all analyzed PSs. Numerical analyses of EC data distribution for regression models with fixed Tx power are presented in

Figure 10 for one LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle.

Table 10 presents corresponding statistics for regression models (10)–(12) in terms of mean, median, standard deviation, Inter Q1-Q3 Quartile Range (IQR), and number of outliers for the distribution of EC numerical data presented in

Figure 10.

The results presented in

Figure 10 and

Table 10 show that as the Tx power increases, the IQR of EC data expands, indicating greater variability of EC data values. Both the mean and median EC rise with an increase in the LoRa end DV Tx power, accompanied by an increase in standard deviation values (

Table 10). Also, the number of EC data outliers is low (

Table 10), which indicates that only a small proportion of the observed data points fall outside the pattern predicted by the regression models (10)–(12) (

Figure 10). These findings align with regression model predictions visualized in

Figure 7, which present an increase in EC of LoRa end DV with an increase in the Tx power.

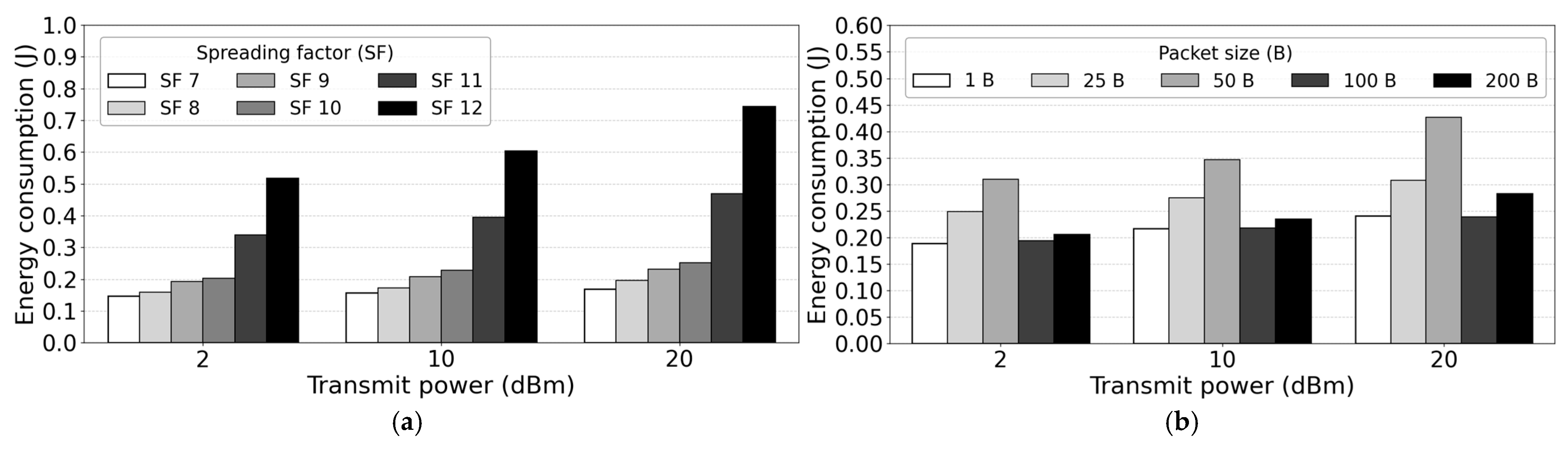

To extend this analysis,

Figure 11a depicts the combined influence of Tx power and SF on mean EC, while

Figure 11b shows mean EC as a function of Tx power and PS. According to

Figure 11a, the mean EC of Lora end DV increases for transmission at higher SFs, which is also proved in the visualization of linear regression models (10)–(12) in

Figure 7.

Figure 11b additionally shows a higher mean EC of LoRa end DV for transmission of LoRa messages having longer PSs. The results for LoRa EC of LoRa message PS equal to 100 B and 200 B deviate from this increasing trend of EC, due to the LoRa Alliance ToA transmission restrictions, which, for higher SFs, do not allow transmission of PS equal to 100 B or 200 B (

Table 1). For that reason, transmission of LoRa messages with PS of 100 B and 200 B in

Figure 11a has a lower EC than the EC of LoRa end DV transmitting PS of 50 B, since the LoRa Alliance ToA restrictions for transmission of LoRa PSs of 100 B and 200 B, stop LoRa message transmission by LoRa end DV for such PSs, which results in lower EC consumption during one transmission and reception cycle (

Table 1).

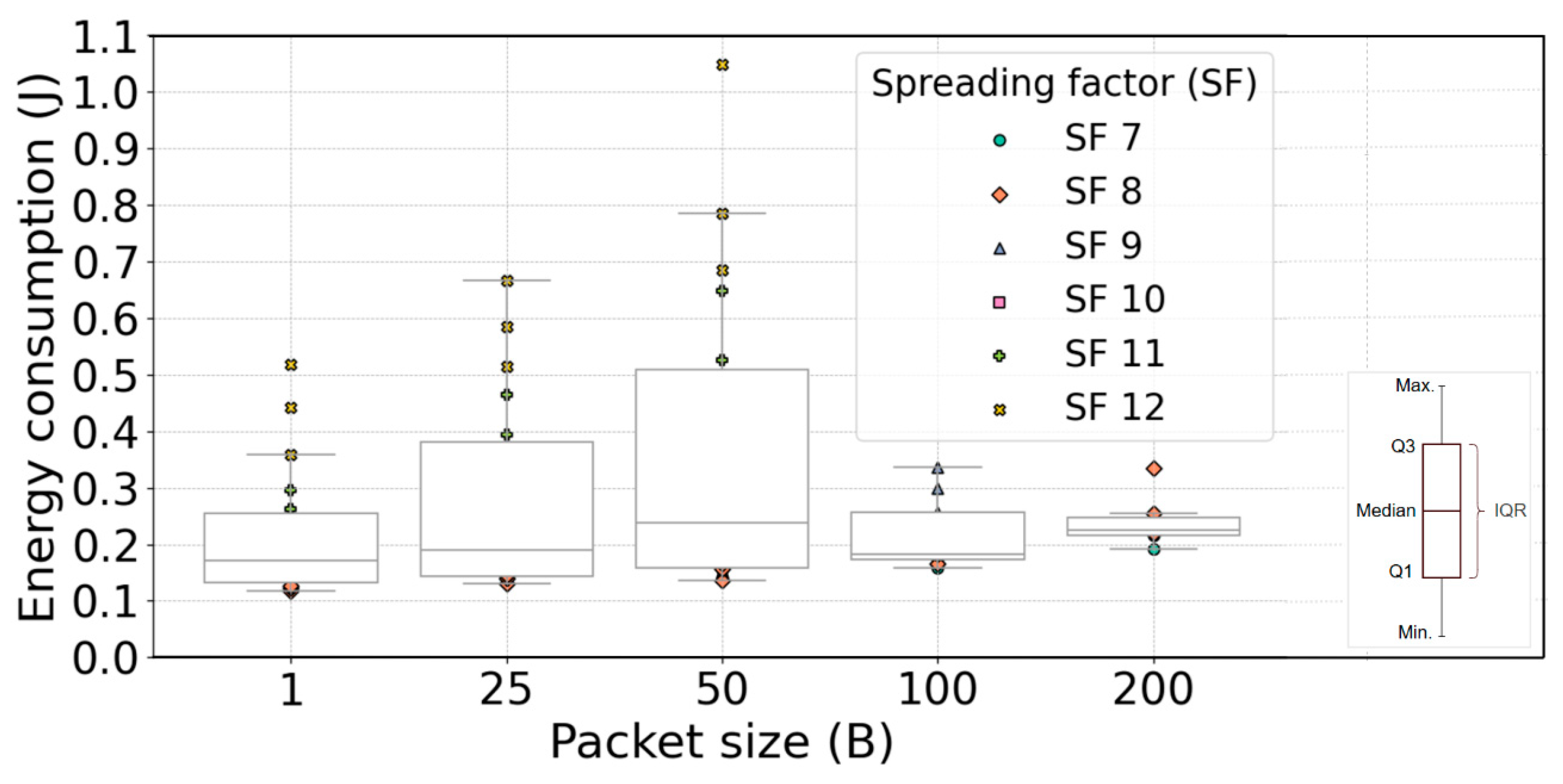

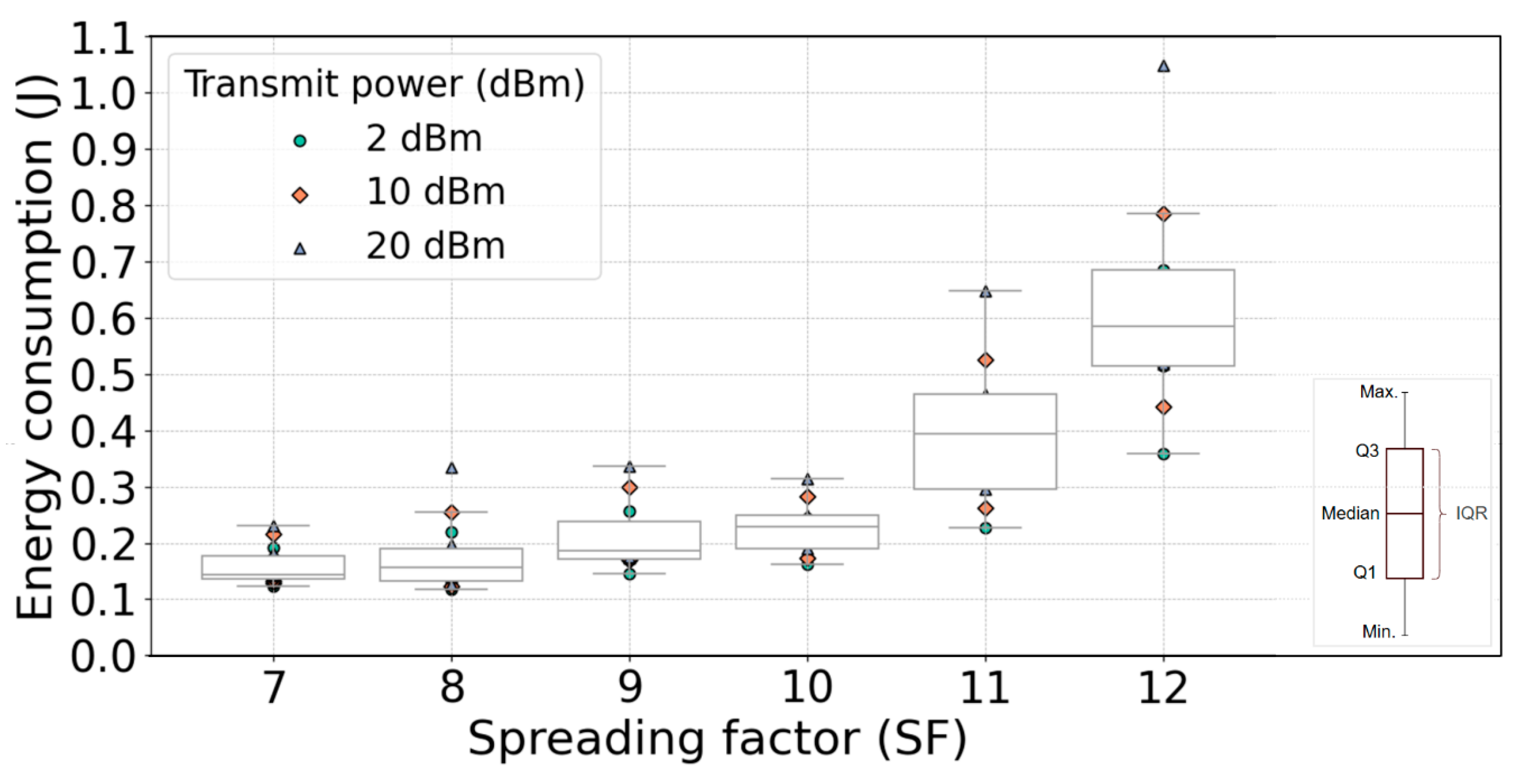

6.2. Numerical Analyses of EC Data Distribution for Regression Models with Fixed PS

Figure 12 displays the boxplot visualization of the distribution of numerical data for regression models (13)–(17), expressing interdependence among the LoRa end DV EC and PS for different SFs and all analyzed Tx power levels. Numerical analyses of EC data distribution for regression models with fixed PS are presented in

Figure 12 for one LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle.

Table 11 presents corresponding statistics for regression models (13)–(17) in terms of mean, median, standard deviation, IQR, and number of outliers for the distribution of EC numerical data presented in

Figure 12.

The results presented in

Table 11 (and

Figure 12) show that EC increases for the transmission of LoRa messages with a larger PS (of up to 50 B). Both the mean and median EC rise with an increase in the LoRa end DV message PS, accompanied by an increase in standard deviation values (

Table 11). Also, statistical results presented in

Table 11 show that for some PSs, there are no EC data outliers or the number of outliers is low, which indicates that most EC data points fit the model well, meaning the model describes the underlying relationship consistently across the dataset (

Figure 12). Transmission with increased PS also results in increased IQR and standard deviation of EC (

Table 11 and

Figure 12), indicating greater variability of numerical data. However, for PSs equal to 100 B and 200 B, the results for mean, median, standard deviation, and IQR deviate from expected (

Figure 12 and

Table 11), since LoRa Alliance restrictions for LoRa message ToA transmission apply to transmissions at the higher SFs (

Table 1).

Figure 13a depicts the combined influence of Tx power and PS on mean EC, while

Figure 13b shows the combined influence of SF and PS on the mean EC of LoRa end DV. Results presented in

Figure 13a indicate that the mean EC increases with increasing PS, and also the transmission at higher Tx powers increases LoRa end DV EC. These findings are aligned with developed regression models (13)–(17) visualized in

Figure 8, which present an increase in EC with an increase in the Tx power and SF. The EC data for LoRa message PS equal to 100 B and 200 B remains lower compared to the transmission of LoRa messages having 50 B PS, since transmission of such LoRa message PSs can be performed only at lower SFs due to LoRa Alliance ToA restrictions. In

Figure 13b, polynomial growth of EC for transmissions having higher SFs and PSs is evident. However, higher PS values equal to 100 B and 200 B lack EC data for some SF combinations (SF11 and SF12), due to LoRa Alliance regulatory restrictions on ToA, according to which transmitting LoRa messages at such a combination of transmission parameters is not allowed (

Table 1).

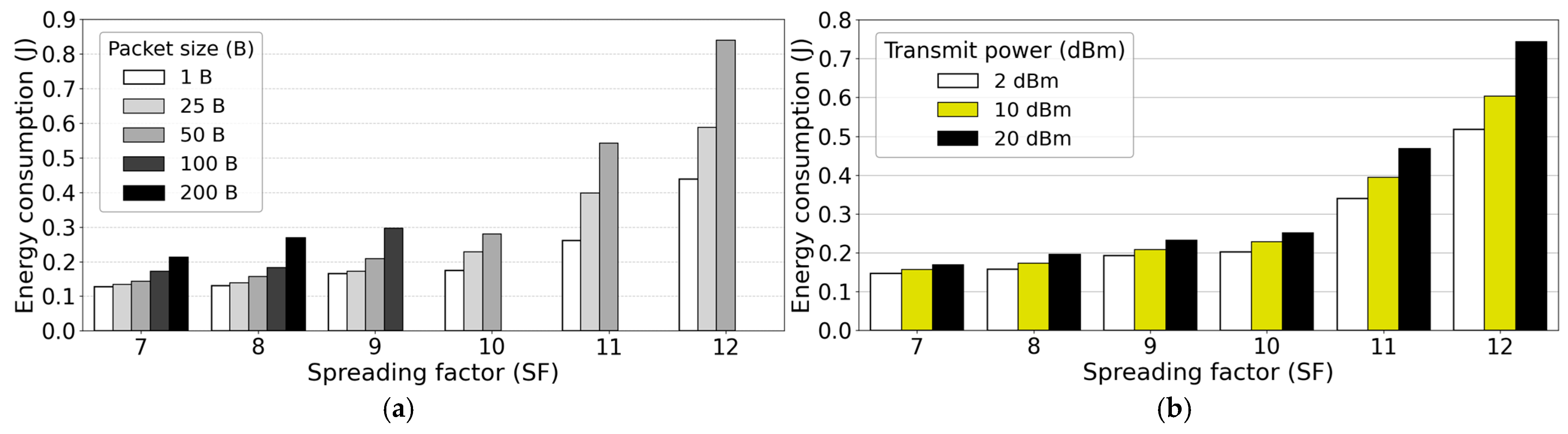

6.3. Numerical Analyses of EC Data Distribution for Regression Models with Fixed SF

Figure 14 displays the boxplot visualization of the distribution of numerical data for regression models (18)–(23), expressing interdependence among the LoRa end DV EC and SF for different Tx power levels and all analyzed LoRa message PSs. Numerical analyses of EC data distribution for regression models with fixed SFs are presented in

Figure 12 for one LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle.

Table 12 presents corresponding statistics for regression models (18)–(23) in terms of mean, median, standard deviation, IQR, and number of outliers for the distribution of EC numerical data presented in

Figure 14.

The results presented in

Table 12 (and

Figure 14) show that EC increases for the transmission of LoRa messages with a larger SF. Both the mean and median EC rise with an increase in the LoRa end DV message PS (

Table 11). Also, statistical results presented in

Table 11 show that for some SFs, there are no EC data outliers or the number of outliers is low, which indicates that a negligible number of observed data points fall outside the pattern predicted by the regression models (

Figure 14). Transmission with increased SFs also results in variable IQR and standard deviation of EC (

Table 11 and

Figure 12), indicating greater variability of numerical data.

Figure 15a depicts the combined influence of SF and PS on mean EC, while

Figure 15b shows the combined influence of SF and Tx power on the mean EC of LoRa end DV. Results presented in

Figure 13a indicate that the mean EC increases for transmission with higher SFs and higher Tx powers. These findings are aligned with developed regression models (18)–(23) visualized in

Figure 9, which present an increase in EC with an increase in the Tx power and PS. The EC data for transmission at SFs equal to SF10, SF11, and SF12 have not been presented in

Figure 15a, due to Lora Alliance ToA restrictions that limit transmission of larger PSs at the highest SFs. In

Figure 15b, the growth of LoRa end DV EC for transmissions having higher SFs and Tx powers is evident, with the highest EC for the combination of LoRa end DV transmit parameters that include the highest levels of SFs and Tx powers.

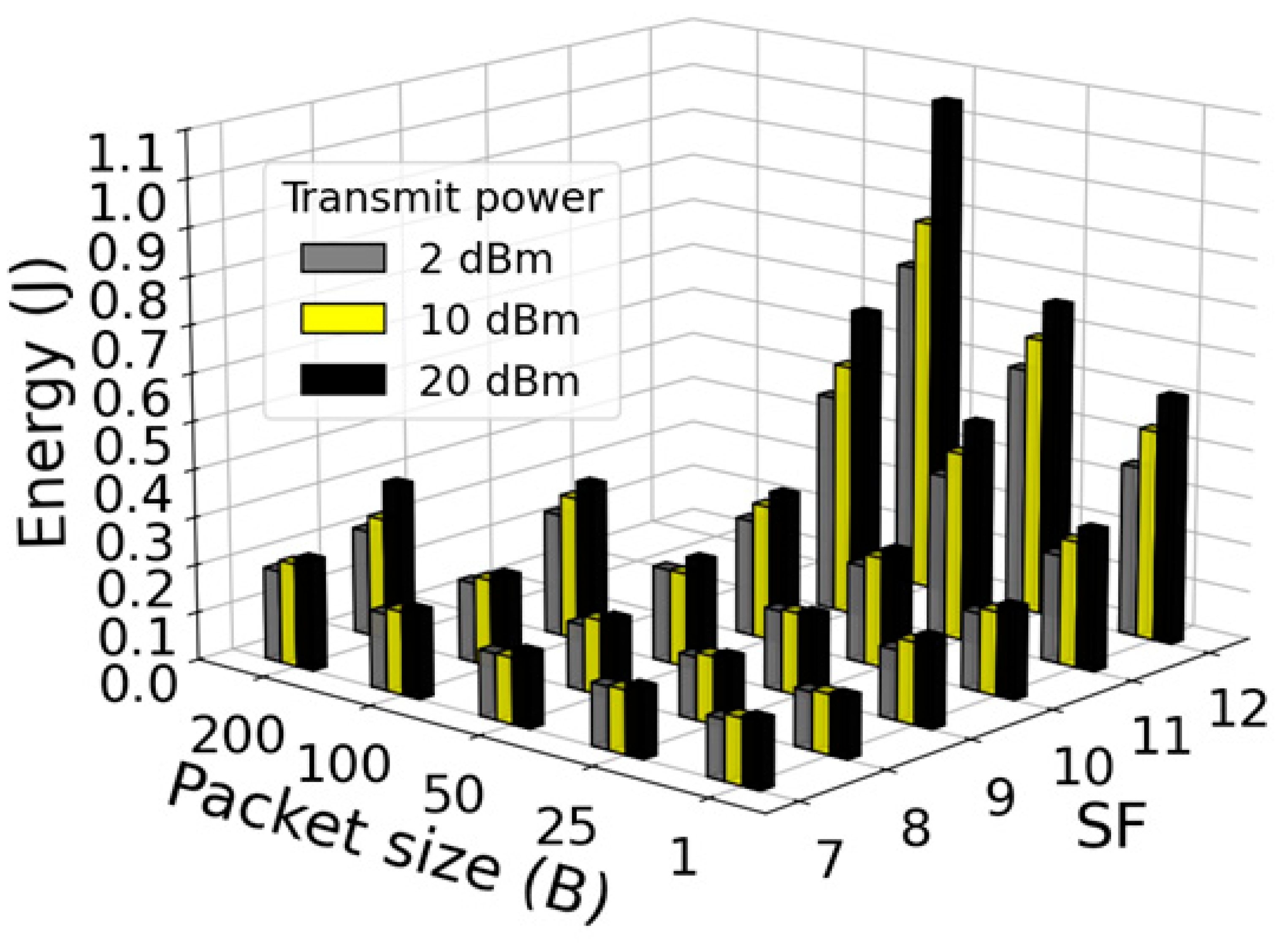

6.4. Mean EC Distribution for All Regression Models

The 3D visualization of developed regression models mean EC distribution for LoRa end DV transmission at Tx power levels of 2 dBm, 10 dBm, and 20 dBm, SFs ranging from SF7 to SF12, and PSs ranging from 1 B to 200 B is presented in

Figure 16.

Figure 16 presents the mean EC data for one Class A LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle. The comparative analysis of LoRa end DV mean EC presented in

Figure 16 for one transmission and reception cycle, confirms clear transmission parameter-dependent patterns of LoRa end DV mean EC. Regression models’ (10)–(23) mean EC results presented in

Figure 16 acknowledge that the mean EC increases when transmission of LoRa end DV occurs at higher Tx powers, PSs, and SFs. According to

Figure 16, the SF transmission parameter exerts the strongest individual influence on LoRa end DV mean EC during one transmission and reception cycle. Also, the Tx power and PS as individual transmission parameters are associated with nearly linear increases in the mean EC of LoRa end DV during one transmission and reception cycle. Due to LoRA Alliance regulatory restrictions for ToA duration of LoRa message transmission explained in the previous sections,

Figure 16 lacks the regression model results of mean EC for transmission parameter combinations characterized with the highest PSs (100 B–250 B) and highest SFs (SF10–F12).

Overall, the regression model results presented in

Figure 16 confirm that Tx power, SF, and LoRa message PS represent the transmission parameters that have a dominant impact on the mean LoRa end DV EC during one transmission and reception cycle. The mean EC for different combinations of analysed transmission parameters can vary up to 8.87 times between the minimum and maximum values in one LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle. Therefore, the appropriate selection of LoRa end DV transmission parameters can significantly contribute to extending the battery longevity of Class A LoRa end DVs.

6.5. Calculation of LoRa End DV Long-Term EC

The presented multiple linear regression models (10)–(23) express the EC of one LoRa end DV transmission and reception cycle (

Figure 3), for LoRa end DVs operating in Class A mode of operation. However, in practical implementations, the LoRa end DVs are envisioned to operate constantly during long time periods with optimized EC. Calculation of the LoRa end DV long-term EC can be done based on the following relation

where

represents the number of transmission and reception cycles during the analysed time period T,

represents the EC of LoRa end DV during one transmission and reception cycle. The

can be calculated for a specific combination of Tx power, SF, and PS transmit parameters based on relations (10)–(23), respectively. The

represents the EC of LoRa Class A end DV between two consecutive LoRa message transmission and reception cycles (

Figure 3). The

depend on duty cycle intensity, which is defined by regulatory rules for the maximum allowed transmission period of consecutive LoRa messages during a one-hour period. According to relation (24), it can be calculated as the multiplication of the number of LoRa messages sent per hour (

) by the number of hours for the period T (

). The

can be calculated as the multiplication of the average LoRa end DV current consumption in the sleep operating state (

), the LoRa end DV sleep operating state voltage (

), and the duration of the duty cycle delay (

between two consecutive LoRa message transmissions (

Figure 3), which also depends on regulatory duty cycle restrictions. For example, the sleep state instantaneous power consumption (

) for the LoRa end DV analysed in this work equals 60 mW. Therefore, the relation (24) enables precise estimation of the LoRa end DV EC for a specific longer time period T.

6.6. Limitations of the Proposed LoRa End DV Multiple Linear Regression Models

The presented multiple linear regression models (10)–(23) have limitations related to the specific constraints implemented in the development process of regression models. Firstly, these constraints are related to the operating mode of LoRa end DV to which the regression models can be implemented. Therefore, the developed multiple linear EC regression models (10)–(23) can be implemented only for LoRa end DVs operating in the Class A operating mode (

Figure 2). For the LoRa end DV operating in Class B or Class C operating mode, the developed LoRa end DV multiple linear EC regression models cannot be implemented, since regression models have been developed based on comprehensive electric current measurements performed for LoRa end DV operating in the Class A operating mode. The development of multiple regression models for LoRa end DVs operating in the Class B and Class C operating modes will be the subject of future research work. Nevertheless, since the majority of LoRa end DVs operate in Class A operating mode, the multiple linear EC regression models presented in this work have an important practical value.

Secondly, multiple linear EC regression models presented in this work are developed based on the results of electric current measurement of the specific LoRa end DV, having a specific transceiver module RFM95W (presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 4). Therefore, the developed multiple linear EC regression models precisely reflect the EC behavior for different LoRa end DV transmission parameters of that specific LoRa end DV transmission module. However,

Figure 6 and

Table 5 indicate that the electric currents of LoRa end DV during one transmission and reception cycle are relatively small. Therefore, the developed multiple linear EC regression models can be generalized to be implemented in the calculation of LoRa end DV EC of other LoRa end DV manufacturers. Since small absolute values of electric current consumption mean small differences among the electric current consumptions among LoRa end DVs of different manufacturers, this generalization can be done due to small differences in EC among LoRa end DVs of different manufacturers. In addition, this generalization can be acceptable for at least the purpose of assessing the LoRa end DV battery lifetime in case of operating with different combinations of transmission parameters and duty cycles in Class A operating mode.

Also, multiple linear regression modes were developed for LoRa end DV operating in the 125 kHz wireless channel bandwidth. However, the LoRa end DV can operate with higher wireless channel bandwidths equal to 250 kHz and 500 kHz. For LoRa end DV operating in these channel bandwidths, the presented multiple linear regression models cannot be used, since linear regression models presented in this work have been developed base on precise and comprehensive electric current measurements for LoRa end DV operating in 125 kHz channel bandwidth. It is reasonable to expect that LoRa end DVs operating in 250 kHz and 500 kHz channel bandwidths will have higher overall energy consumption for the same transmission parameter configuration. Thus, the development of regression modes for energy consumption of LoRa end DV operating in 250 kHz and 500 kHz will be one of the goals of future work.

7. Conclusions

EC of LoRa end DVs represents a crucial aspect of IoT deployments, given that these DVs are typically installed in large quantities and are expected to operate autonomously over extended periods in remote and energy-constrained environments. Knowing the exact EC of LoRa end DVs during a specific period is necessary for estimating the DV operating duration, implementation feasibility, and scalability, which makes the optimization of LoRa end DV energy usage a key design requirement. For these reasons, this paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the impact of different combinations of LoRa end DV transmission parameters on the LoRa end DV EC. The analysis is performed by combining theoretical insights of the LoRaWAN protocol architecture with experimental measurement results of LoRa end DV electric current consumption, which is measured during the operation of LoRa end DV under different combinations of the transmission parameter configurations.

The particular emphasis in the paper was given to the development of regression models expressing the impact of different combinations of Tx power, PS, and SF transmission parameters, on EC of LoRa end DV operating in the Class A mode during one LoRa message transmission and reception cycle. A total of 14 multiple linear regression models expressing the interdependence of LoRa end DV EC on different combinations of transmission parameters were developed. Each developed multiple linear regression model was mathematically formulated to capture the joint effects of two transmission parameters on EC of LoRa end DV, for the specific fixed value of the third parameter. The presented statistical goodness-of-fit analyses confirm high accuracy and predictive strength of the proposed regression models.