Abstract

Millions of people suffer from Musculoskeletal System Disorders (MSDs), including Karen people who work hard in the fields for their subsistence and have done so for generations. This has forced the Karen to use many medicinal plants to treat MSDs. We gathered data from 15 original references covering 27 Karen communities and we document 461 reports of the use of 175 species for treating MSDs among the Karen people in Thailand. The data were analyzed by calculating use values (UV), relative frequency of citation (RFC) and informant consensus factor (ICF). Many use reports and species were from Leguminosae and Zingiberaceae. Roots and leaves were the most used parts, while the preferred preparation methods were decoction and burning. Oral ingestion was the most common form of administration. The most common ailment was muscle pain. Sambucus javanica and Plantago major were the most important species because they had the highest and second-highest values for both UV and RFC, respectively. This study revealed that the Karen people in Thailand use various medicinal plants to treat MSDs. These are the main resources for the further development of inexpensive treatments of MSDs that would benefit not only the Karen, but all people who suffer from MSD.

1. Introduction

Traditional knowledge of medicinal plants is transferred from generation to generation in local communities [1]. Plants are used over a lifetime from birth to death [2]. Although modern medicines are much used everywhere around the world, traditional medicines are still important to many people, especially among ethnic minority groups [3,4] and in developing countries [5,6,7,8]. For example, a high proportion of the population in Africa, Chile, and Pakistan, still rely on traditional medicine [9,10]. The uses of medicinal plants are still popular because they are inexpensive, easy to use, and they have limited side effects compared to modern medicines [11].

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are non-communicable diseases and they are dramatically increasing in many developing and developed countries [12]. More than 1.7 billion people throughout the world suffer from these ailments, causing both disability and death [13]. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that MSDs, such as osteoarthritis, arthritis, back and neck pain, and bone fractures, are the second most common cause of disability in the world [14]. These disorders do not only occur among the elderly, but also hit adolescent people because they work hard throughout life. About 20–33% of the world’s population have experienced painful and disabling muscular-skeleton conditions. In the USA, one of two adults have suffered from such ailments [14]. In Europe, MSDs are one of the most common causes of severe long-term pains and disabilities, leading to significant healthcare and social support costs [15]. In addition, limited mobility, and adroitness, caused by MSDs, can lead to the loss of work and reduced capability in social roles [14]. In Asia, there is a high prevalence of arthritis in all countries, but especially in India and China [16].

People from many parts of the world have used a number of medicinal plants for treating ailments related to MSDs, such as muscular pain, rheumatism, fractured bones, etc. Studies in Turkey [17] and Pakistan [10] listed 142 plant species, which were traditionally used to treat MSDs, mostly rheumatism. Moreover, professional farmers are much affected by MSDs. For example, farmers in southeast Kansas (USA) [18], the Netherlands [19], Britain, and Ireland [20] were reported to suffer injuries from MSDs. Important ailments of MSDs included osteoarthritis, lower back pain, upper limb disorders, sprains, fractures, and dislocations [21].

In Thailand, the consequences of MSDs are severe. Thailand is an agricultural country in which rice farming occupies over half of the total agricultural area [22]. Farmers’ physical activities include excessive bending, twisting, kneeling, and carrying loads, which have caused many ailments related to MSDs [12,23,24,25]. These ailments commonly affect the lower back, shoulders, hands/wrists and knees [26,27]. However, even if Thailand has been the subject of many ethnomedicinal studies, none of them have focused on medicinal plants to treat MSDs (e.g., Kantasrila [28] and Kaewsangsai [29]).

Here, we studied the Karen, who are the largest ethnic minority group in Thailand. The Karen people live, mostly, in the Tak, Mae Hong Son, Chiang Mai, Ratchaburi, and Kanchanaburi provinces. Most of them settle in the mountainous areas above 500 m above sea level. Their livelihoods are based on agriculture [28,29,30] and they cultivate rice in swidden fields around their villages using only a few agricultural machines [28,31]. They spend a long time bending their body which, in turn, produces a high risk of back injury, muscular pain, and fatigue from farming. Treatments in hospitals, which are often located far away from their villages, take a long time and cost both time and money [28]. Thus, most rural farmers use traditional treatments that involve many medicinal plants to cure their ailments.

Accordingly, it is important to document ethnobotanical information among the Karen to find: (1) How many species of plants are used to treat MSDs? (2) What are the most important plant species and families used for treating MSDs? (3) What are the preferred plant parts and methods of preparation of plants for treating MSDs? (4) Which of the MSD categories has the highest prevalence among the Karen and which plants are used to treat them? The outcome of this research could facilitate the identification and selection of plant species as effective treatments for MSD patients.

2. Results

2.1. Medicinal Plant Diversity

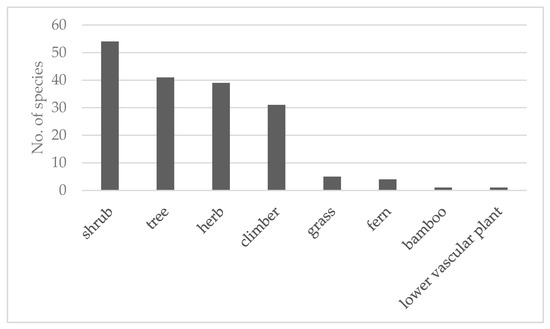

A total of 461 use reports were compiled from 15 references that covered 27 villages from the Chiang Mai and Mae Hong Son provinces in northern Thailand and the Kanchanaburi, Ratchaburi, and Tak provinces in western Thailand. The use reports related to 175 species in 144 genera and 75 families, as shown in Table 1 and Table S1. Most of them (170 spp.) were flowering plants, including 53 species of shrubs, 41 species of trees, 39 species of herbs, 31 species of climbers, 5species of grass and 1 species of bamboo, as shown in Figure 1. The families with most species of MSD medicinal plants were Leguminosae (12 species, 31 use reports), Zingiberaceae (10 species, 19 use reports), Rubiaceae (9 species, 10 use reports), and Asteraceae (8 species, 36 use reports).

Table 1.

Medicinal plants used to treat Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among the Karen ethnic minority in Thailand.

Figure 1.

Habit of the medicinal plants used to treat MSDs among the Karen in Thailand.

2.2. Plant Part Used, Preparation and Routes of Administration

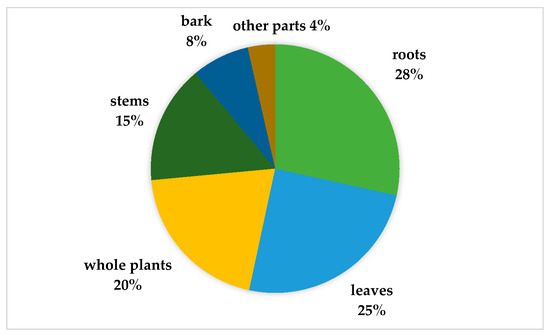

In terms of plant parts used, they were significantly different between the use reports of each part (Chi-square test, p < 0.05). The root was the most used part for treating MSDs. It was mentioned in 28% of all use reports, followed by leaves (25%) and whole plants (20%), respectively, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Plant parts used to treat MSDs among Karen communities in Thailand.

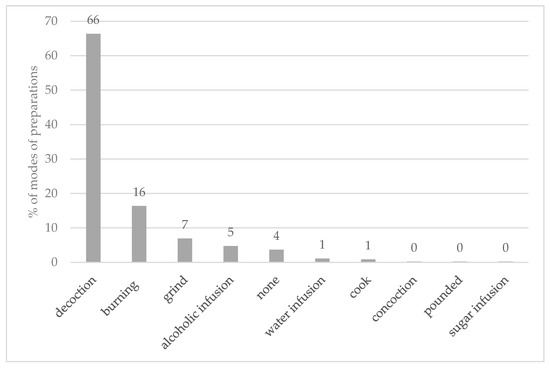

Considering the mode of preparation of medicinal plants to treat MSDs, the use reports of preparation were significantly different between the methods (Chi-square test, p < 0.05). There were many methods for preparing medicinal plants, as shown in Figure 3. Among these, decoction and burning were most common, contributing 66% and 16%, respectively, of the total use-reports.

Figure 3.

Modes of preparation of medicinal plants used to treat MSD among the Karen in Table 2. Musculoskeletal Disorders Categories.

Regarding the route of administration, there were diverse ways of using medicinal plants. Oral ingestion was the most preferred method (68%), which was significantly different from the other applications (Chi-square test, p < 0.05), followed by poultices (21%). Eaten as food, compress, bath, steaming, chewing, liniment, and soak had low use reports.

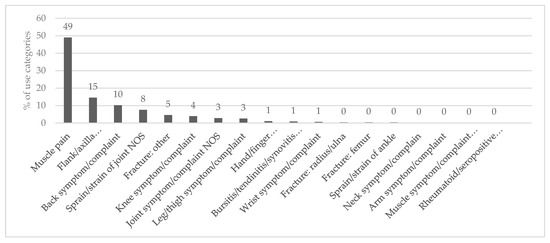

The 461 reports belonged to 18 use categories, as shown in Figure 4, according to the International Classification of Primary Care [32]. They were significantly different between the use reports of each category (Chi-square test, p < 0.05). The largest category was muscular pain (49%), followed by flank/axilla symptom/complaint (15%) and back symptom/complaint (10%), respectively. In the other extreme, there was only one report for each of the following use categories: neck symptom/complain, arm symptom/complaint, muscle symptom/complaint NOS (Not Otherwise Specified), and rheumatoid/seropositive arthritis.

Figure 4.

Categories of MSDs treated with medicinal plants among the Karen in Thailand.

Sometimes different plants were used to treat the same ailment using the same preparation in different Karen villages. For example, in 16 villages they used the leaves of Sambucus javanica Reinw. ex Blume, to treat fractured bones and muscle pains by burning them, then placing them on the painful areas. The leaves of Plantago major L. were ground and put on the painful joints. This was reported from ten villages. Many species were reported for their uses in more than one use category. For instance, Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC, was used to treat back pains (back symptom/complaint), lumbar pains (flank/axilla symptom/complaint), muscle pains (muscle pain), and sprains (sprain/strain of joint NOS), as shown in Table 1.

2.3. Ethnobotanical Indices: UV, RFC, and ICF

2.3.1. Use Values (UV) of the Ethnomedicinal Plants for Treating MSDs

UVs, calculated to compare the importance of the different species of medicinal plants, ranged from 0.037–1.148. Species with high UVs included: Sambucus javanica (1.148), Plantago major (0.852), Miliusa thorelii Finet and Gagnep (0.704), Pothos scandens L. (0.630), Sambucus simpsonii Rehder (0.481), Blumea balsamifera (0.407), and Duhaldea cappa (Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don) Pruski and Anderb. (0.407), as shown in Table 1. At the other extreme, a large number of medicinal plants (49%) were cited only once for their uses to treat MSD ailments.

2.3.2. The Relative Frequency of Citations (RFC) of the Ethnomedicinal Plants

The RFC ranged from 0.593–0.037. The plant with the highest RFC value was Sambucus javanica (0.593) followed by Plantago major (0.370), Gmelina arborea Roxb. (0.296), Duhaldea cappa (0.259), Miliusa thorelii (0.259), Pothos scandens (0.259), Sambucus simpsonii (0.259), and Elephantopus scaber L. (0.222). However, it should be noted that more than half of the medicinal plants used to treat MSDs had low RFC values (RFC = 0.037). These plants were known in only one village, as shown in Table 1.

2.3.3. The Information Consensus Factors (ICF) of MSD Categories

The Information consensus factors (ICF) ranged from 0–0.75, as shown in Table 2. The ailment category with the highest ICF was hand/finger symptom/complaint (0.75), followed by fracture: other (0.67), sprain/strain of joint NOS (not otherwise specified) (0.58), joint symptom/complaint NOS (0.56), bursitis/tendinitis/synovitis NOS (0.50), and wrist symptom/complaint (0.50) categories. On the other hand, there were seven categories with the ICF values equal to zero, including arm symptom/complaint, fracture: femur, fracture: radius/ulna, muscle symptom/complaint, neck symptom/complain, and rheumatoid/seropositive.

Table 2.

Values for Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) recorded among Karen communities in Thailand, divided per use category following the International Classification of Primary Care [32].

3. Discussion

3.1. Diversity of Medicinal Plant Used to Treat MSD

There was a high diversity of medicinal plants used to treat MSDs among the Karen communities. These plants make up 30% of all medicinal plant species in Thailand, when compared with the review of ethnobotanical knowledge about medicinal plants to treat MSDs in Thailand [33]. This implies that MSDs have a high prevalence among the Karen in Thailand. That may be why they use so many plant species to treat these ailments. It should be noted that the number of medicinal MSD plants is different in different villages. Many villages had a high number of MSD plants. Many medicinal plants were used in only a single village. This shows that the knowledge of plant used to deal with MSDs could originate independently in individual villages. Moreover, knowledge is hard to exchange among different villages because of their isolation.

Leguminosae were the most prominent family for treating MSD among the Thai Karen people, which agrees with other ethnomedicinal research around the world [34,35,36,37]. Leguminosae were reported to have the highest number of medicinal plant species used to treat MSDs in northern Pakistan [10]. Many species of the family are used by local people in different parts of world to cure ailments [38]. Moreover, it was also one of the dominant families in ethnobotanical plant surveys, with the highest number of use reports and used species among several ethnic groups in Thailand [33]. The Karen used many medicinal Leguminosae and still maintain a substantial traditional plant knowledge [39]. Leguminosae is one among the largest plant families globally [40] and it is found in various habitats and attains various life forms. Therefore, it was selected for use in highland regions of southeast Asia [41]. Other plant families with many medicinal plant species were Zingiberaceae, Asteraceae, and Rubiaceae, which also have many species in Thailand [33,42]. Asteraceae is another large family, together with Leguminosae, in terms of global numbers of species [43]. Both families have many species that are used to treat MSD ailments [10]. All these families are also dominant in other ethnobotanical studies in Thailand [33].

Shrubs and trees were the most common life forms of the plants harvested by the Karen people for traditional medicine for MSDs. Trees were especially commonly used for MSD treatments in other parts of the world, such as India [37], Ghana [44], Peru, and South America [45].

3.2. Plant Utilization: Parts, Preparation, and Routes of Administration

Leaves and roots were the most used parts in the treatment of MSDs, similar to what has been found in other studies in Thailand, such as the ethnobotany of the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand [46,47], and the review of all ethnomedicinal uses of plants in Thailand [33]. Leaves were reported as the most used part in several other ethnomedicinal studies of MSD treatments around the world, such as in Algeria [48], Central Africa [49,50], India [37], Italy [51], Kenya [52], Papua New Guinea [53], and South Africa [54]. Additionally, leaves and roots were greatly used for the treatment of MSDs in northern Pakistan [10]. Leaves are often preferred because they can be harvest easier than other parts of the plant [46,55]. Moreover, leaves are rich in secondary metabolites because they are the site of photosynthesis [49,56]. Another much used part was the root because some bioactive compounds are preserved in roots in higher concentrations than in other parts [57].

The most used method of preparation was decoction. This method is common for preparing medicinal plants in Thailand [33,58] and around the world, such as in Central Africa [59], China [60], eastern Nicaragua [61], northern Pakistan [10], and the Philippines [35]. Decoction is the easiest way to extract bioactive substances from plant materials [33]. Moreover, sweeteners, such as sugar or honey, can be added to the decoction during or after the preparation to adjust the taste and reduce the bitterness of the medicines [33,62,63]. Besides drinking, the decoction could also be applied externally (e.g., in bathing) [64].

The preferred route of administration was oral ingestion. It was reported to be the most common method of administration in other studies in Thailand [46,47] and many areas around the world, such as India [37] and Papua New Guinea [65,66]. Other favored routes of administration were poultices and eaten as food. Medicinal plants were prepared by grinding and applied directly to the injured parts. In addition, when the plants were crushed or ground, they released their secondary compounds [67,68]. Additionally, eating vegetables as food made patients feel like they did not take any medicine [33]. Medicinal plants, which were prepared as food, could be eaten as fresh vegetables, which is an easy way to prepare them because they can be eaten as a part of the daily diet [64].

3.3. Important Disorder Categories

Most species were used to treat ailments in the muscular pain category. This result was similar to reports from other areas, such as northern Pakistan [10] and Spain [69]. The muscular pain category was a dominant MSD category, and many communities around the world have used many medicinal plants to treat it [70]. Famers have used many medicinal plants to treat muscle pain caused by laborious work in the fields [71]. They spend a lot of time cultivating rice without the help of agricultural machines, which may cause muscle pain. In addition, many medicinal plants were used to treat flank/axilla symptom/complaint and back symptom/complaint. According to previous research, the most prevalent MSD in farmers was pain in the lower back due to physical activities, such as excessive bending, twisting, and carrying of loads [12]. Moreover, these activities commonly affected other parts of the body, such as the shoulders, hands/wrists, and knees among the farmers [12,23,24,25,26,27].

3.4. Important Plants for Treating MSD

3.4.1. Most Preferred Species for Treating MSD

The UVs depend on use reports and the commonness of plants around the studied areas. Plant species with high UV values indicated that they had use reports and were commonly found in the studied areas [33,72]. UV could be calculated to show which species were important to the communities, while RFC determined the level of traditional knowledge about the use of medicinal plants in the study areas. When the RFC values were high, it referred to common popularity, utilization, and priority species among informants for curing specific ailments [10]. The most important plant for treating MSDs among the Karen people was Sambucus javanica. It had both high UVs and RFC values. It was used in many categories of MSD (e.g., flank/axilla symptom/complaint, fracture, joint symptom/complaint, leg/thigh symptom/complaint, muscle pain, sprain/strain of joint and wrist symptom/complaint). Moreover, it was reported in 16 (60%) of the 27 villages for which we had data. This plant is well known for its medicinal properties among villagers of many other ethnic groups in Thailand. It is used for treating bone fractures and muscle pain by the Akha [58,73], the Hmong [74], the Karen [58], the Lua [74], the Mien [58,74], and the Thai Yuan communities [74]. Another species in the same genus, Sambucus simpsonii, also had high UVs and RFC values. This plant is the cultivated version of S. javanica and it was used as a substitute for S. javanica. Other species in this genus have been reported to have phytochemical contents with anti-inflammatory and anti-analgesic properties, which may be directly related to their use for treating MSDs. One example is Sambucus williamsii Hance, which is used to treat bone and joint diseases in China [75]. It has compounds, such as phenolics and terpenoids, which have anti-inflammatory effects [75]. The root extract of Sambucus ebulus L., also had anti-inflammatory and anti-analgesic effects [76]. Elderberry, Sambucus nigra L., is known for its phenolics and flavonoids with similar antioxidant activity [77].

Other species with high UV and RFC values were Plantago major, Miliusa thorelii, Pothos scandens, Gmelina arborea, Elephantopus scaber, Duhaldea cappa, and Blumea balsamifera. These species were reported in many Karen villages and were used to treat ailments in many MSD categories. Some of them are cosmopolitan, such as Plantago major, and they are easy to collect for use. This plant was reported as being used in eight MSD categories, such as back symptom/complaint, flank/axilla symptom/complaint, muscle pain, etc. It contains iridoids with relenting anti-inflammatory activity that could relieve MSD [78]. Many ethnic groups, including Karen [58], Tai-Yai [79], Mien [58,79] Akha [58], and Hmong [58], also used it to treat rheumatic ailments, bone fractures, and muscle pains [58,78,79]. Blumea balsamifera has been used for traditional medicine for thousands of years in Southeast Asia [80]. Moreover, this plant has chemical compounds with anti-inflammatory [81] and antioxidant effects [80,82].

Gmelina arborea [83,84], Elephantopus scaber [85,86], and Duhaldea cappa [87], were also used for their anti-inflammatory properties. For instance, Gmelina arborea [84] and Elephantopus scaber [85,86] have flavonoids, tannins, and saponins. Miliusa thorelii and Pothos scandens have been used for curing many MSD categories in this study, such as fractures, joint symptoms, and muscle pains, but any phytochemicals that could affect MSD remain to be documented in these species.

3.4.2. Important Species in Important Disorders

High ICF values indicate a high level of agreement between informants in terms of using medicinal plants to treat diseases [88]. In addition, high ICF values are important for selecting plants for studies of their bioactive compounds [89]. However, the values of ICF should be considered, together with the number of use reports. Categories with low numbers of use reports could give rise to unusually high ICF values. For example, the category, hand/finger symptom/complaint, had the highest ICF value, 0.75. However, only five use reports from two species were recorded for this category, including Curcuma elata Roxb. and Plantago major. Other categories also had high ICF values, including fracture: other, sprain/strain of joint, joint symptom/complaint, bursitis/tendinitis/synovitis, and wrist symptom/complaint. The Fracture: other category had the second highest ICF value, but it had few citations and plant species. The most popular species in this group were Sambucus javanica and Sambucus simpsonii. Both categories, sprain/strain of joint and joint symptom/complaint, had relatively few use reports and species when compared with muscle pain categories, which had the highest use value and number of species. However, considering the use reports of these groups, it appears that the informants had similar knowledge about plant uses. The species which were the most popular among informants in sprain/strain of joint and joint symptom/complaint were Sambucus javanica (27% of total use report) and Plantago major (13% of total use report), respectively. On the other hand, bursitis/tendinitis/synovitis and wrist symptom/complaint had very low numbers of both the use reports and the species. There were two species with three use reports. Some medicinal plants were reported to treat bursitis/tendinitis/synovitis and wrist symptom/complaint, including Flacourtia rukam Zoll. and Moritzi, Bistorta paleacea (Wall. ex Hook.f.) Yonek. and H. Ohashi, Sambucus javanica and Tupistra muricata (Gagnep.) N. Tanaka, respectively. This implies that these categories were not prevalent among the informants.

The muscle pain category had the highest numbers of citations and species used. The ICF value of this group was 0.38, demonstrating a great diversity in the knowledge of medicinal plants for the treatment of ailments in the muscle pain category. The most popular species in this group were Blumea balsamifera and Sambucus javanica, both with high values for use values.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

The data about medicinal plants used for treating MSD by the Karen in Thailand were compiled from 15 ethnobotanical references, which included unpublished scientific reports and published journal articles, as shown in Table 3. The references were produced in the period 1995–2017. They were extracted from online theses of the Thai Library Integrated System, which cover all theses of Thai universities. Some additional data were extracted from theses and un-published research reports of the Ethnobotany and Northern Thai Flora Laboratory, Department of Biology, Chiang Mai University. In order to avoid data duplication, we followed the procedure proposed by Phumthum et al. [33] by excluding research articles and duplicated research studies by the same authors and study areas. In total, 27 Karen villages were covered by the data in this review, including 21 villages in the Chiang Mai province, two villages in the Mae Hong Son and Ratchaburi provinces, and one village in each of the Tak and Kanchanaburi provinces.

Table 3.

The 15 references from which we extracted original data on medicinal plants species used to treat musculoskeletal system disorders among Karen communities in Thailand.

4.2. Data Organization

The scientific species and family names of the medicinal plants were verified following Plants of The World Online and Flora of Thailand. Plant use data were classified into medicinal categories of MSDs following the International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition (ICPC-2) [32]. The ICPC-2 classification system is based on body system. The disorders were classified according to specific body systems or to non-specific categories: not otherwise specified (NOS). For example, the muscle pain category included specific sub-categories, such as fibromyalgia, fibrositis, myalgia, panniculitis, and rheumatism, whereas other disorders involving the muscles of the body were classified into muscle system/complaint NOS categories. The vernacular names were as mentioned in the references. The parts of the plants used were derived from the references and classified into: roots, leaves, stem, bark, inflorescences, infructescence, whole plants, aerial parts, and not specified. Methods of preparation and routes of administration followed the original reports.

4.3. Data Analysis

The ethnobotanical knowledge was collected as “use report”. Each “use report” refers to the use of a specific species with a specific method of preparation, which was used to treat an ailment in an MSD category in a Karen village. Because this is a meta-analysis where we only knew the village studied and not the individual informants interviewed, we used the village as a “pseudoinformant” in our analysis. The pseudoinformant was a representative of traditional knowledge about the medicinal plant usage of each village. It showed all medicinal plant species to treat the MSDs of each village. Therefore, if the data reported that a species was used to treat the same MSD category, but it had different methods of preparation, then each method was counted as a separate use report. For example, if species A was boiled for drinking or burned for a body compress to treat muscle pain, then these were counted as two use reports. The significant differences of use reports among different categories were analyzed by a Chi-square test with α = 0.05. This analysis was performed by SPSS software, version 17. The Chi-square test was performed to test significant difference among the studied variables of use reports with α = 0.05. Moreover, ethnobotanical indices were used in order to find the important and preferred medicinal plants for treating MSD among the Karen. These methods were modified from Phumthum et al. [33].

4.3.1. Use Value (UV) Modified from:

UV = (∑Ui)/N

Use values are high when there are many use reports for a plant, implying that the plant is important, and in contrast, UVs approach zero when there are few reports related to its use [105].

4.3.2. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

This index showed the local importance of each plant used among the informants. It was calculated as:

where FC is the number of pseudoinformants who mention the use of the species and N is the total number of pseudoinformants who participated in the study (27).

RFC = FC/N

The value of RFC ranges from 0 to 1. When RFC is 0, it means no informant use the species in question. On the other hand, RFC is equal to 1 when all informants mention the use of the species [106].

4.3.3. Informant Consensus Factor (ICF)

This index was used to analyze the rank of agreement among informants for medicinal plants used in each category [107]. The ICF was calculated as:

where Nur refers to the number of use reports for a particular use category and Nt refers to the number of taxa recorded in that same category. ICF is low (near 0) when most informants report different plants for a category. This would imply that plants were chosen randomly for use in that category or no exchange of information had occurred about the medicinal plants used among informants. However, the ICF value is high (approaching 1) when a few plants are reported by a high proportion of informants for the same use, also implying that the exchange of knowledge had occurred between informants [108].

ICF = (Nur − Nt)/(Nur − 1)

5. Conclusions

Our review compiles ethnobotanical knowledge of the Karen people about plants used to treat musculoskeletal disorders. We found 175 medicinal plant species belonging to 144 genera and 75 families. The most important species were Sambucus javanica and Plantago major, which had the highest and second-highest for both UV and RFC values, respectively, while the most important plant families were Leguminosae and Zingiberaceae. The uses could be divided into 18 categories of musculoskeletal ailments. Muscular pain had highest prevalence among the Karen communities.

Our review can lead to the discovery of the alternative medicines to treat MSDs. Future investigations of phytochemical compounds and pharmacological research are needed to confirm the efficacy of treatments that are part of traditional knowledge. Finally, besides medicinal information, this review emphasizes the importance of traditional knowledge.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/9/7/811/s1, Table S1: The reference and number of pseudo informants of medicinal plants used to treat Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among the Karen ethnic minority in Thailand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K.; methodology, R.K., P.P., and A.I.; formal analysis, R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.; writing—review and editing, P.P., H.B., and A.I.; supervision, H.P., H.B., P.W., and A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Human Resource Development in Science Project (Science Achievement Scholarship of Thailand, SAST) and the Research Center in Bioresources for Agriculture, Industry and Medicine, Chiang Mai University partly financially supported the research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all authors of the cited works for the primary information. We are also thankful to the Human Resource Development in Science Project (Science Achievement Scholarship of Thailand, SAST) for supporting the PhD study of R.K. and the Research Center in Bioresources for Agriculture, Industry and Medicine, Chiang Mai University for the partial financial support. H.B. thanks the Carlsberg foundation CF14-0245 for their support to the Flora of Thailand project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Pieroni, A.; Quave, C.L. Traditional pharmacopoeias and medicines among Albanians and Italians in southern Italy: A comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 101, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamxay, V.; de Boer, H.J.; Björk, L. Traditions and plant use during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum recovery by the Kry ethnic group in Lao PDR. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Hernandez, P.; Abegunde, D.; Edejer, T. The World Medicines Situation 2011. Medicine Expenditures; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, R.W. The globalization of traditional medicine in Northern Perú: From shamanism to molecules. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asase, A.; Kadera, M.L. Herbal medicines for child healthcare from Ghana. J. Herb. Med. 2014, 4, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giday, K.; Lenaerts, L.; Gebrehiwot, K.; Yirga, G.; Verbist, B.; Muys, B. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from degraded dry afromontane forest in northern Ethiopia: Species, uses and conservation challenges. J. Herb. Med. 2016, 6, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpodar, M.S.; Lawson-Evi, P.; Bakoma, B.; Eklu-Gadegbeku, K.; Agbonon, A.; Aklikokou, K.; Gbeassor, M. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus in south of Togo (Maritime Region). J. Herb. Med. 2015, 5, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, P.; Ward, A. Complementary medicine in Europe. Br. Med. J. 1994, 309, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, K.; Ahmad, M.; Zhang, G.; Rashid, N.; Zafar, M.; Sultana, S.; Shah, S.N. Traditional plant based medicines used to treat musculoskeletal disorders in Northern Pakistan. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 19, 17–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payyappallimana, U. Role of traditional medicine in primary health care: An overview of perspectives and challenging. Yokohama J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 14, 723–743. [Google Scholar]

- Puntumetakul, R.; Siritaratiwat, W.; Boonprakob, Y.; Eungpinichpong, W.; Puntumetakul, M. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in farmers: Case study in Sila, Muang Khon Kaen, Khon Kaen province. J. Med. Tech. Phys. Ther. 2011, 23, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Hignett, S.; Fray, M. Manual handling in healthcare. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the Federation of the European Ergonomics Societies (FEES), Bruges, Belgium, 10–12 October 2010; pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Musculoskeletal Conditions. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Musculoskeletal Health in Europe, Report v5.0 (internet). 2012. Musculoskeletal Health in Europe, Report v5.0. eumusc.net. Available online: http://www.eumusc.net/myuploaddata/files/musculoskeletal health in Europe report v5.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Brennan-Olsen, S.L.; Cook, S.; Leech, M.; Bowe, S.J.; Kowal, P.; Naidoo, N.; Ackerman, I.; Page, R.; Hosking, S.; Pasco, J. Prevalence of arthritis according to age, sex and socioeconomic status in six low and middle income countries: Analysis of data from the World Health Organization study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) Wave 1. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tümen, İ.; Akkol, E.K.; Taştan, H.; Süntar, I.; Kurtca, M. Research on the antioxidant, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory activities and the phytochemical composition of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 211, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosecrance, J.; Rodgers, G.; Merlino, L. Low back pain and musculoskeletal symptoms among Kansas farmers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, E.; Oude Vrielink, H.H.; Huirne, R.B.; Metz, J.H. Risk factors for sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders among self-employed Dutch farmers: A case-control study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, S.; Ruane, D.J.; McNamara, J.; Kinsella, A.; McNamara, A. Disability on Irish farms—A real concern. J. Agromed. 2009, 14, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.; O’Sullivan, L. Psychosocial risk exposures and musculoskeletal disorders across working-age males and females. Hum. Factors Ergon. Man. Serv. Ind. 2010, 20, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area of Holding by Land Use. 2013. Available online: http://web.nso.go.th/en/census/agricult/cen_agri03.htm (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Holmberg, S.; Stiernström, E.-L.; Thelin, A.; Svärdsudd, K. Musculoskeletal symptoms among farmers and non-farmers: A population-based study. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 8, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker-Bone, K.; Palmer, K. Musculoskeletal disorders in farmers and farm workers. Occup. Med. 2002, 52, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangwilai, T.; Norkaew, S.; Siriwong, W. Factors associated with musculoskeletal disorders among rice farmers: Cross sectional study in Tarnlalord sub-district, Phimai district, Nakhonratchasima province, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2014, 28, S85–S91. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, M.; Hwang, S.; Stark, A.; May, J.; Hallman, E.; Pantea, C. An analysis of self-reported joint pain among New York farmers. J. Agric. Saf. Health 2003, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douphrate, D.I.; Nonnenmann, M.W.; Rosecrance, J.C. Ergonomics in industrialized dairy operations. J. Agromed. 2009, 14, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantasrila, R. Ehtnobotany of Karen at Ban Wa Do Kro, Mae Song Sub-District, Tha Song Yang District, Tak Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewsangsai, S. Ethnobotany of Karen in the Royal Project Extended Area Khun Tuen Noi Village, Omkoi District, Chiang Mai Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sinphiphat, S. Hill Tribe People in Thailand; Hill Tribe Research Institute Department of Public Welfare, Ministry of Interior: Bangkok, Thailand, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Junsongduang, A.; Balslev, H.; Inta, A.; Jampeetong, A.; Wangpakapattanawong, P. Medicinal plants from swidden fallows and sacred forest of the Karen and the Lawa in Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wonca International Classification Committee (WICC). International Classification of Primary Care, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Phumthum, M.; Srithi, K.; Inta, A.; Junsongduang, A.; Tangjitman, K.; Pongamornkul, W.; Trisonthi, C.; Balslev, H. Ethnomedicinal plant diversity in Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 214, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.; Vijayakumar, S.; Yabesh, J.M.; Ravichandran, K.; Sakthivel, B. Documentation and quantitative analysis of the local knowledge on medicinal plants in Kalrayan hills of Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, H.G.; Kim, Y.-D. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants used by the Ati Negrito indigenous group in Guimaras island, Philippines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K. An ethnobotanical study of plants used for the treatment of livestock diseases in Tikamgarh District of Bundelkhand, Central India. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, S460–S467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, R.; Vijayakumar, S.; Prabhu, S.; Yabesh, J.G.E.M. Quantitative traditional knowledge of medicinal plants used to treat livestock diseases from Kudavasal taluk of Thiruvarur district, Tamil Nadu, India. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekeesoon, D.P.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants and animals used in the treatment and management of pain in Mauritius. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutjaritjai, N.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Balslev, H.; Inta, A. Traditional uses of Leguminosae among the Karen in Thailand. Plant J. 2019, 8, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marles, R.J.; Farnsworth, N.R. Antidiabetic plants and their active constituents. Phytomedicine 1995, 2, 137–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.G.; Kim, Y.D. Medicinal plants for gastrointestinal diseases among the Kuki-Chin ethnolinguistic groups across Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar: A comparative and network analysis study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooma, R.; Suddee, S. Tem Smitinand’s Thai Plant Names, Revised; The Office of the Forest Herbarium, Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014.

- Stevens, P.F. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 14. 2001. Available online: http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/ (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Addo-Fordjour, P.; Kofi Anning, A.; Durosimi Belford, E.J.; Akonnor, D. Diversity and conservation of medicinal plants in the Bomaa community of the Brong Ahafo region, Ghana. Med. Plant Res. 2008, 2, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Biset, J.; Campos-de-la-Cruz, J.; Epiquién-Rivera, M.A.; Canigueral, S. A first survey on the medicinal plants of the Chazuta valley (Peruvian Amazon). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srithi, K.; Balslev, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Srisanga, P.; Trisonthi, C. Medicinal plant knowledge and its erosion among the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 123, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panyaphu, K.; Van On, T.; Sirisa-Ard, P.; Srisa-Nga, P.; ChansaKaow, S.; Nathakarnkitkul, S. Medicinal plants of the Mien (Yao) in Northern Thailand and their potential value in the primary healthcare of postpartum women. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouelbani, R.; Bensari, S.; Mouas, T.N.; Khelifi, D. Ethnobotanical investigations on plants used in folk medicine in the regions of Constantine and Mila (North-East of Algeria). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 194, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yemele, M.; Telefo, P.; Lienou, L.; Tagne, S.; Fodouop, C.; Goka, C.; Lemfack, M.; Moundipa, F. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for pregnant women’ s health conditions in Menoua division-West Cameroon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 160, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompermaier, L.; Marzocco, S.; Adesso, S.; Monizi, M.; Schwaiger, S.; Neinhuis, C.; Stuppner, H.; Lautenschläger, T. Medicinal plants of northern Angola and their anti-inflammatory properties. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 216, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, P.; Di Marzio, P.; Guarrera, P.; Iorizzi, M. Ethnobotanical study on the medicinal plants in the Mainarde Mountains (central-southern Apennine, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 184, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukungu, N.; Abuga, K.; Okalebo, F.; Ingwela, R.; Mwangi, J. Medicinal plants used for management of malaria among the Luhya community of Kakamega East sub-County, Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 194, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Kehop, D.A.; Kinminja, B.; Sabak, M.; Wavimbukie, G.; Barrows, K.M.; Matainaho, T.K.; Barrows, L.R.; Rai, P.P. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the East Sepik province of Papua New Guinea. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asowata-Ayodele, A.M.; Afolayan, A.J.; Otunola, G.A. Ethnobotanical survey of culinary herbs and spices used in the traditional medicinal system of Nkonkobe Municipality, Eastern Cape, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 104, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giday, M.; Asfaw, Z.; Woldu, Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, S.; Chaudhary, R.P.; Taylor, R.S. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the people of Manang district, central Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.U.; Muhammad, G.; Hussain, M.A.; Bukhari, S.N. Cydonia oblonga M.—A medicinal plant rich in phytonutrients for pharmaceuticals. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.F. Plant and People of the Golden Triangle: Ethnobotany of the Hill Tribe of the Northern Thailand; Whitman College and Desert Botanical Garden: Portland, OR, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Simbo, D.J. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Babungo, Northwest Region, Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dao, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Long, C. Medicinal plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la, Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, F.G.; Anderson, G.J. Ethnobotany of the Garifuna of eastern Nicaragua. Econ. Bot. 1996, 50, 71–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyanar, M.; Ignacimuthu, S. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commonly used by Kani tribals in Tirunelveli hills of Western Ghats, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balangcod, T.D.; Balangcod, A.K.D. Ethnomedical knowledge of plants and healthcare practices among the Kalanguya tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, Philippines. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2011, 10, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Panyadee, P.; Balslev, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Inta, A. Medicinal plants in homegardens of four ethnic groups in Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 239, 111927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waruruai, J.; Sipana, B.; Koch, M.; Barrows, L.R.; Matainaho, T.K.; Rai, P.P. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the Siwai and Buin districts of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 138, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorim, R.Y.; Korape, S.; Legu, W.; Koch, M.; Barrows, L.R.; Matainaho, T.K.; Rai, P.P. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, A.; Bordoloi, M.; Baruah, H.P.D. Aloe vera: A multipurpose industrial crop. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahandideh, M.; Hajimehdipoor, H.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Dehpour, A.; Hassanzadeh, G. A wound healing formulation based on Iranian traditional medicine and its HPTLC fingerprint. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Cavero, R.Y.; Calvo, M.I. Medicinal plants used for musculoskeletal disorders in Navarra and their pharmacological validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, R.W. Role of collagen hydrolysate in bone and joint disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheu. 2000, 30, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inta, A.; Trisonthi, P.; Trisonthi, C. Analysis of traditional knowledge in medicinal plants used by Yuan in Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 149, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.C.; Husby, C.E. Patterns of medicinal plant use: An examination of the Ecuadorian Shuar medicinal flora using contingency table and binomial analyses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inta, A. Ethnobotany and Crop Diversity of Tai Lue and Akha Communities in the Upper Northern Thailand and the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, China. Ph.D. Thesis, Chiang Mai Graduate School, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Srithi, K. Comparative Ethnobotany in Nan Province, Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.H.; Zhang, Y.; Cooper, R.; Yao, X.S.; Wong, M.S. Phytochemicals and potential health effects of Sambucus williamsii Hance (Jiegumu). Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, R.H.M.J.; Bunyapraphatsara, N. Plant Resources of South-East Asia No. 12: Medicinal and poisonous plants 3; Prosea Foundation: Bogor, Indonesia, 2003; p. 664. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, L.; Cabrita, L.; Boas, M.V.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C. Chemical, biochemical and electrochemical assays to evaluate phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of wild plants. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1600–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Padua, L.S.; Bubypraphatsara, N.; Lemmens, R.H.M.J. Plant Resources of South-East Asia No. 12: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants I.; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; p. 711. [Google Scholar]

- Areekun, S.; Onlamun, A. Food Plants and Medicinal Plants of Ethnic Groups in Doi Ang Khang, Chiangmai. Agricultural Development Projects; Kasetsart University: Bankok, Thailand, 1978. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.; Wang, D.; Fan, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, F.; Hu, X.; Wang, K.; Yuan, L. Blumea balsamifera—A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Molecules 2014, 19, 9453–9477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Fu, W.; Fan, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, F. Effect of volatile oil from Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. leaves on wound healing in mice. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 34, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessa, F.; Ismail, Z.; Mohamed, N.; Haris, M.R.H.M. Free radical-scavenging activity of organic extracts and of pure flavonoids of Blumea balsamifera DC leaves. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswala, R.; Patel, V.; Chakraborty, M.; Kamath, J. Phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Gmelina arborea: An overview. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2012, 3, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gandigawad, P.; Poojar, B.; Hodlur, N.; Sori, R.K. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of ethanolic extract of Gmelina arborea in experimental acute and sub-acute inflammatory models in wistar rats. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kabeer, F.A.; Prathapan, R. Phytopharmacological profile of Elephantopus scaber. Pharmacologia 2014, 2, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurtamin, T.; Sudayasa, I.P.; Tien, T. In vitro anti-inflammatory activities of ethanolic extract Elephantopus scaber leaves. Indones. J. Med. Health. 2018, 9, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalola, J.; Shah, R.; Patel, A.; Lahiri, S.K.; Shah, M.B. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities of Inula cappa roots (Compositae). J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangjitman, K.; Wongsawad, C.; Kamwong, K.; Sukkho, T.; Trisonthi, C. Ethnomedicinal plants used for digestive system disorders by the Karen of northern Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaneo, L.R.S.; De Lucena, R.F.P.; de Albuquerque, U.P. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists in an region of Atlantic Forest in the state of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2005, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junsongduang, A. Roles and Importance of Sacred Forest in Biodiversity Conservation in Mae Chaem District, Chiang Mai Province. Ph.D. Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kamwong, K. Ethnobotany of Karens at Ban Mai Sawan and Ban Huay Pu Ling, Ban Luang Sub-District, Chom Thong District, Chiang Mai Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mahawongsanan, A. Change of Herbal Plants Utilization of the Pga K’nyau: A Case study of Ban Huay Som Poy, Mae Tia Watershed, Chom Thong District. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai Province. Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pongamornkul, W. An Ethnobotanical Study of the Karen at Ban Yang Pu Toh and Ban Yang Thung Pong, Chiang Dao District, Chiang Mai Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Puling, W. Ethnobotany of Karen for Studying Medicinal Plants at Angka Noi and Mae Klangluang Villages, Chomthong District, Chiang Mai. Bachelor’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sukkho, T. A Survey of Medicinal Plants Used by Karen People at Ban Chan and Chaem Luang Subdistricts, Mae Chaem District. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai Province. Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tangjitman, K. Vulnerability Prediction of Medicinal Plants Used by Karen People in Chiang Mai Province to Climatic Change Using Species Distribution Model (SDM). Ph.D. Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winjchiyanan, P. Ethnobotany of Karen in Chiang Mai. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sonsupub, B. Ethnobotany of Karen Community in Raipa Village, Huaykhayeng Subdistrict, Thongphaphume District, Kanchanaburi Province. Master’s Thesis, Kasetsart University, Bankok, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moonjai, J. Ethnobotany of Ethnic Group in Mae La Noi District, Mae Hong Son Province. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Trisonthi, C.; Trisonthi, P. Ethnobotanical study in Thailand, a case study in Khun Yuam district Maehongson province. Thai J. Bot. 2009, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Junkhonkaen, J. Ethnobotany of Ban Bowee, Amphoe Suan Phueng, Changwat Ratchaburi. Master’s Thesis, Kasetsart University, Bankok, Thailand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tangjitman, K. Ethnobotany of the Karen at Huay Nam Nak village, Tanaosri subdistrict, Suanphueng district, Ratchaburi province. Thai J. Bot. 2017, 9, 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kantasrila, P.; Pongamornkul, W.; Panyadee, P.; Inta, A. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used by Karen, Tak province in Thailand. Thai J. Bot. 2017, 9, 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, O.; Gentry, A.H. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ. Bot. 1993, 47, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Huanca, T.; Vadez, V.; Leonard, W.; Wilkie, D. Cultural, practical, and economic value of wild plants: A quantitative study in the Bolivian Amazon. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaddegh, M.; Naghibi, F.; Moazzeni, H.; Pirani, A.; Esmaeili, S. Ethnobotanical survey of herbal remedies traditionally used in Kohghiluyeh va Boyer Ahmad province of Iran. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, R.; Logan, M. Informant Consensus: A New Approach for Identifying Potentially Effective Medicinal Plants, Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet, Behavioural Approaches; Redgrave Publishing Company: Bredfort Hill, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).