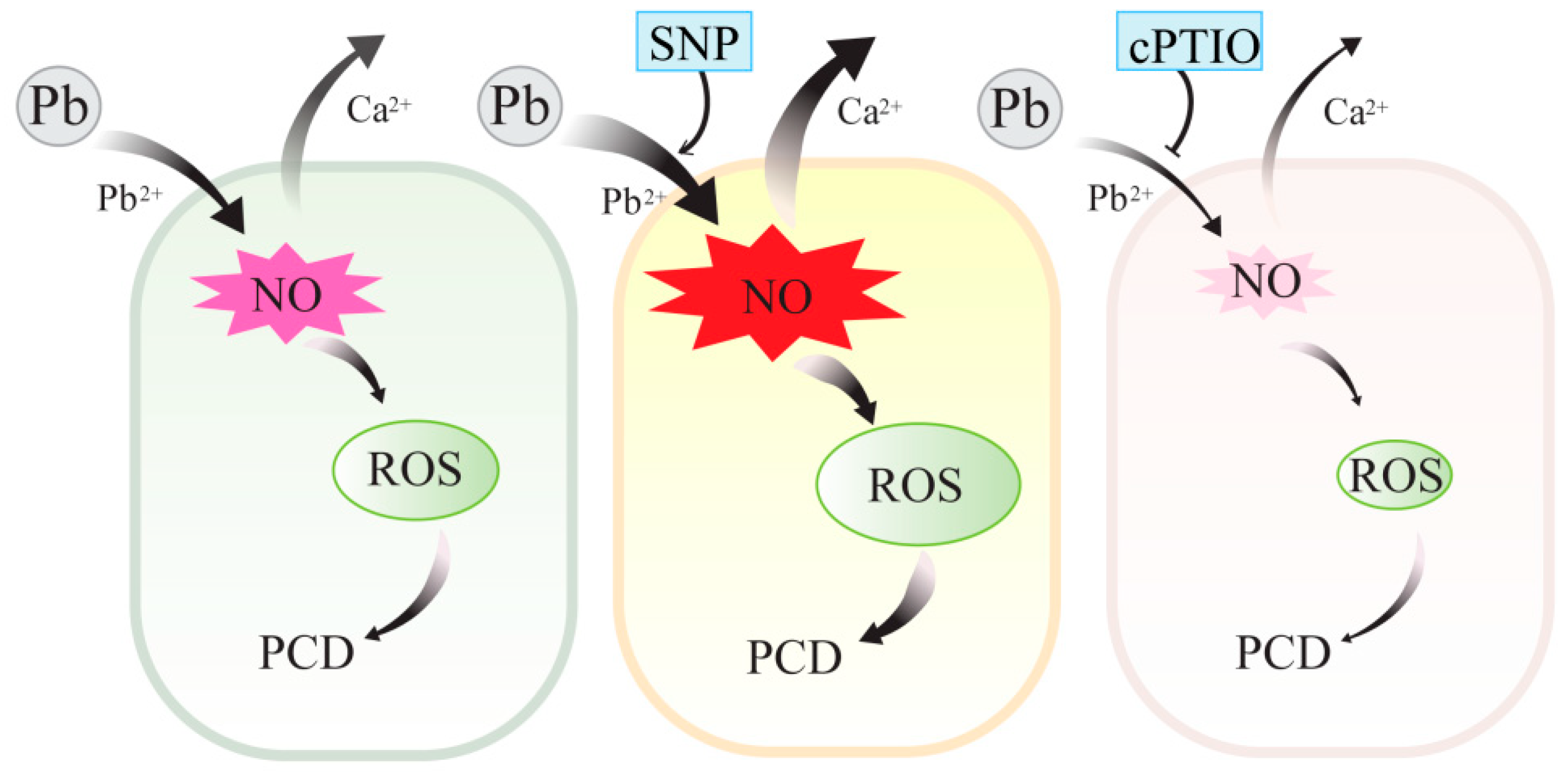

Nitric Oxide Enhances Cytotoxicity of Lead by Modulating the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Is Involved in the Regulation of Pb2+ and Ca2+ Fluxes in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

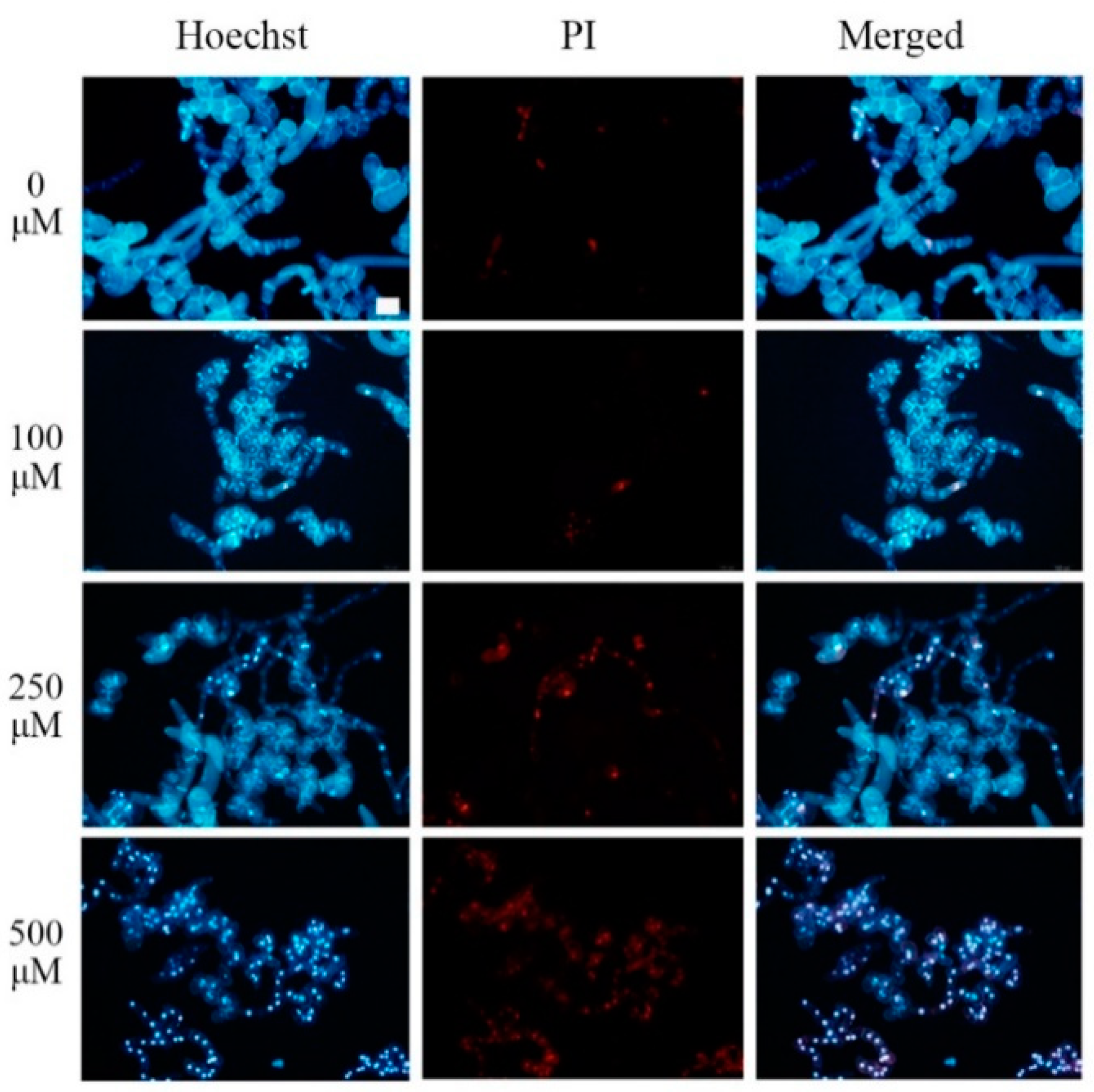

2.1. Pb Induced PCD in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

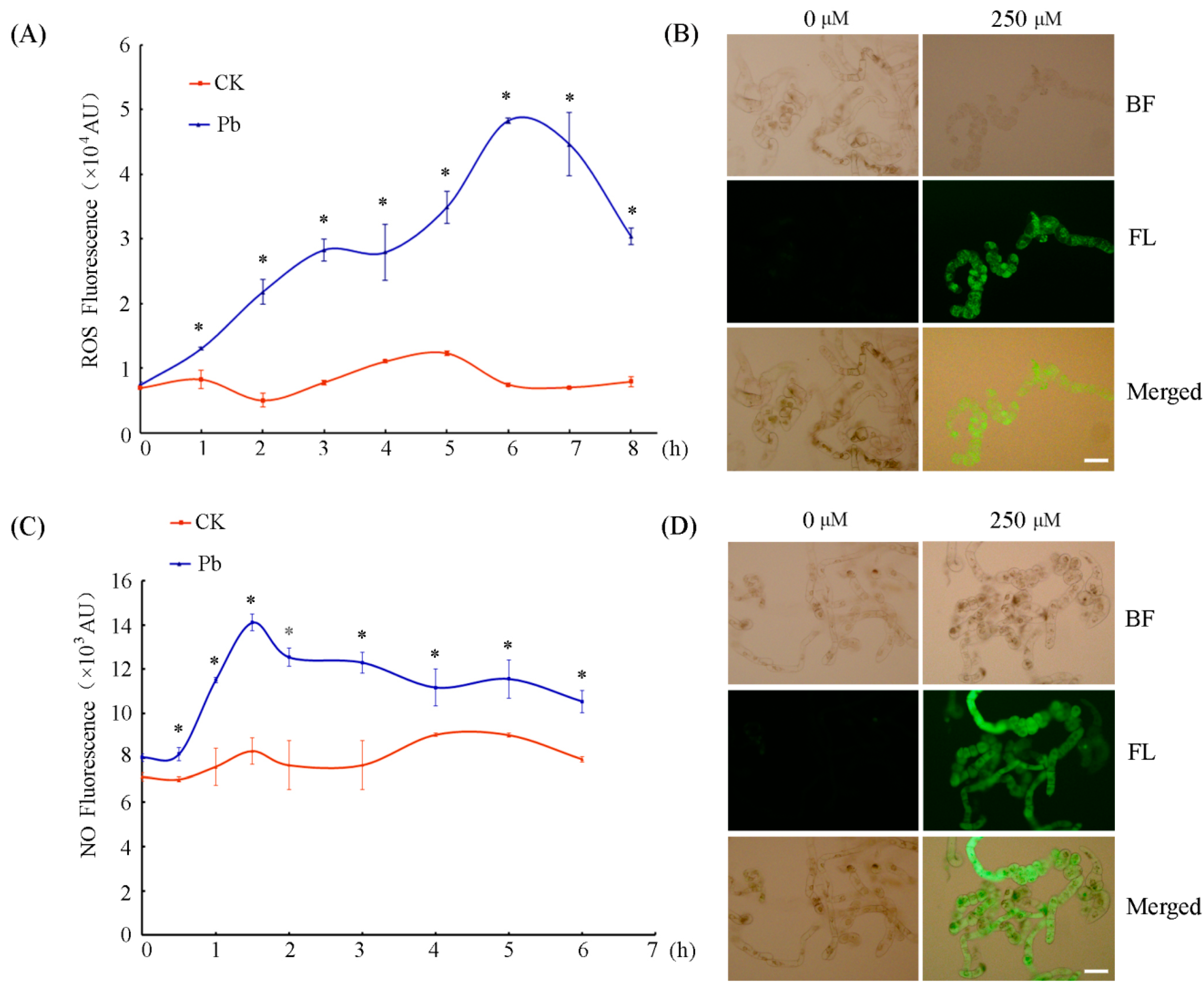

2.2. Pb Triggered ROS and NO Bursts in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

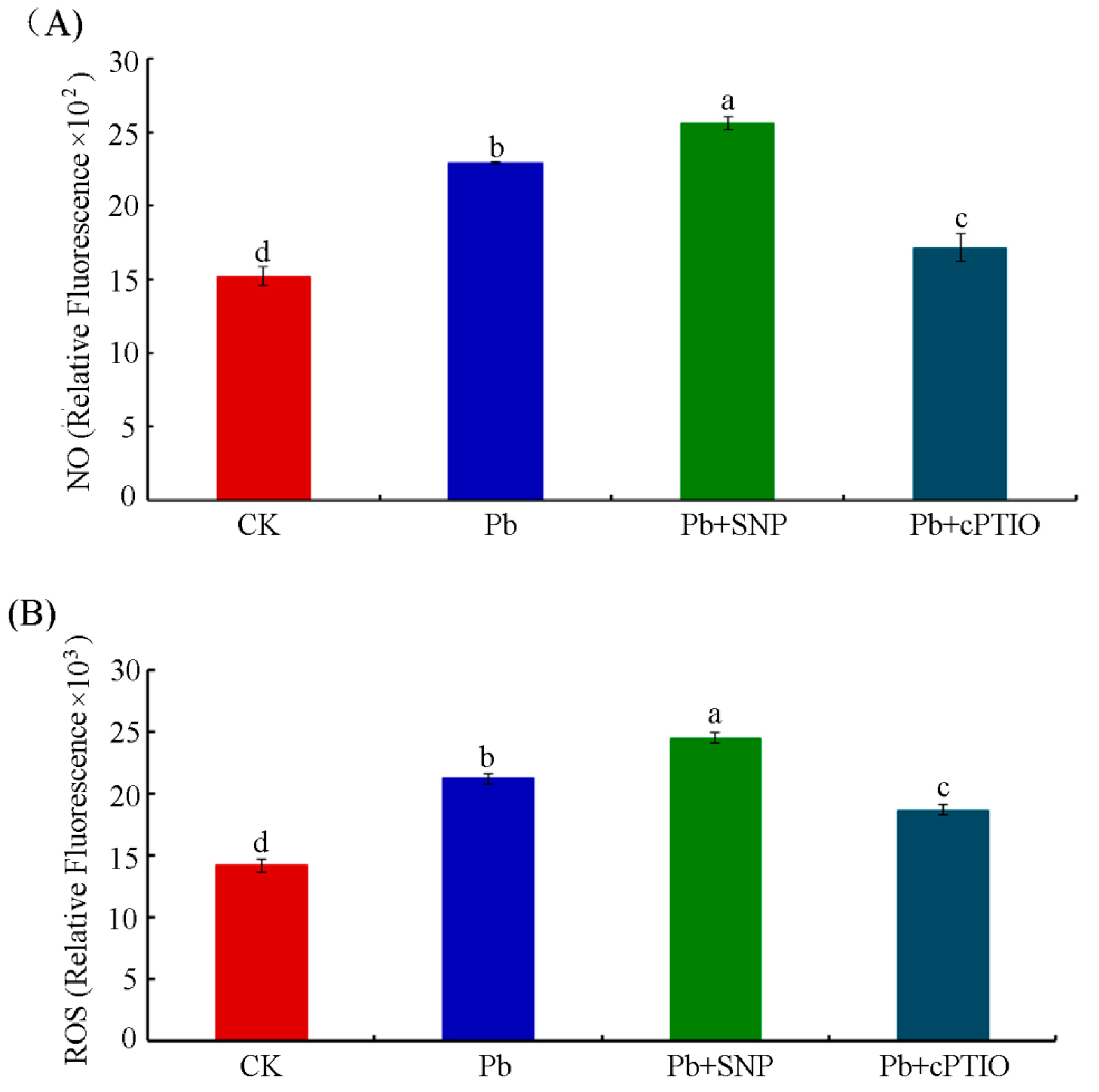

2.3. NO Contributed to Pb-Induced ROS Production in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

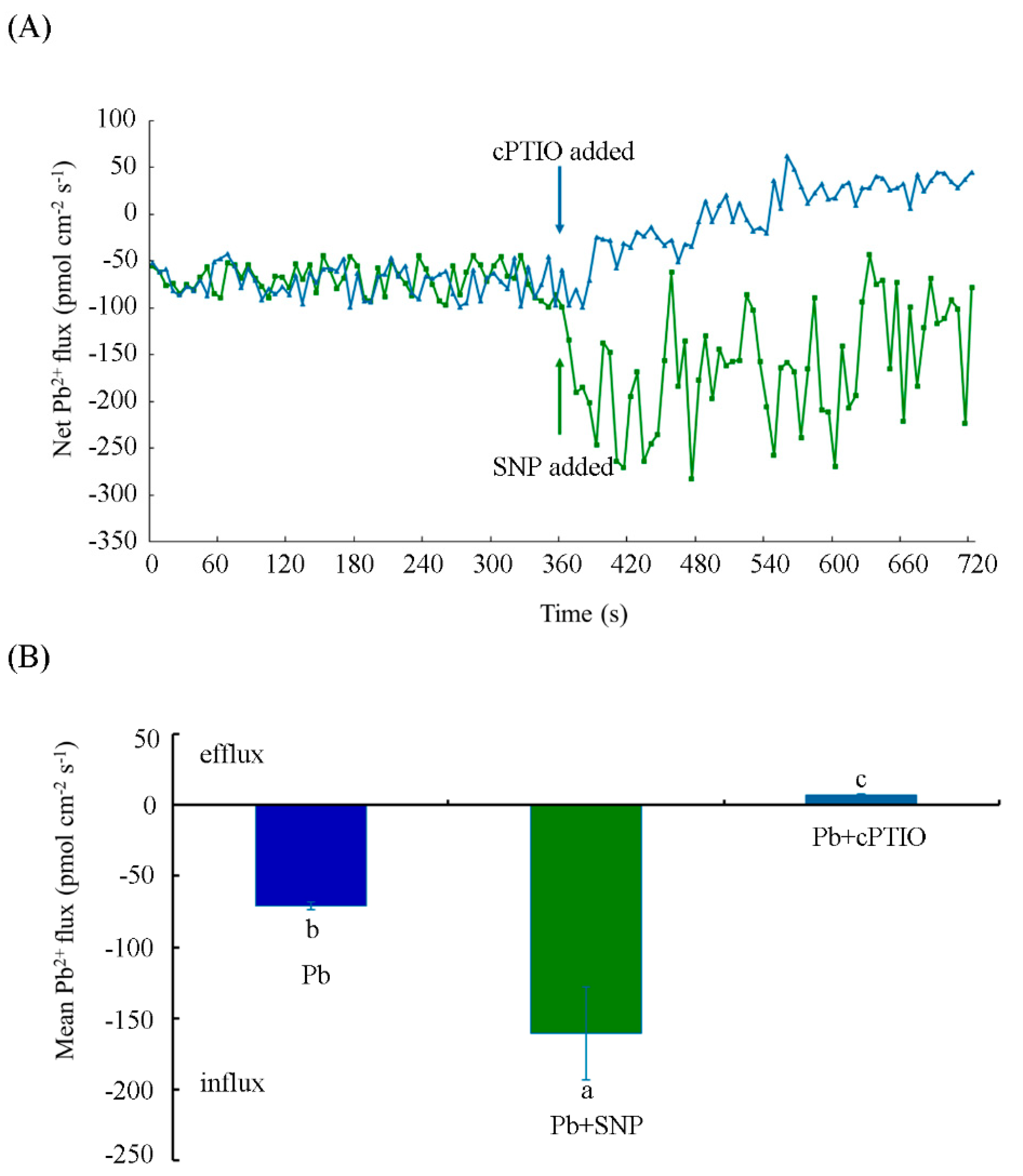

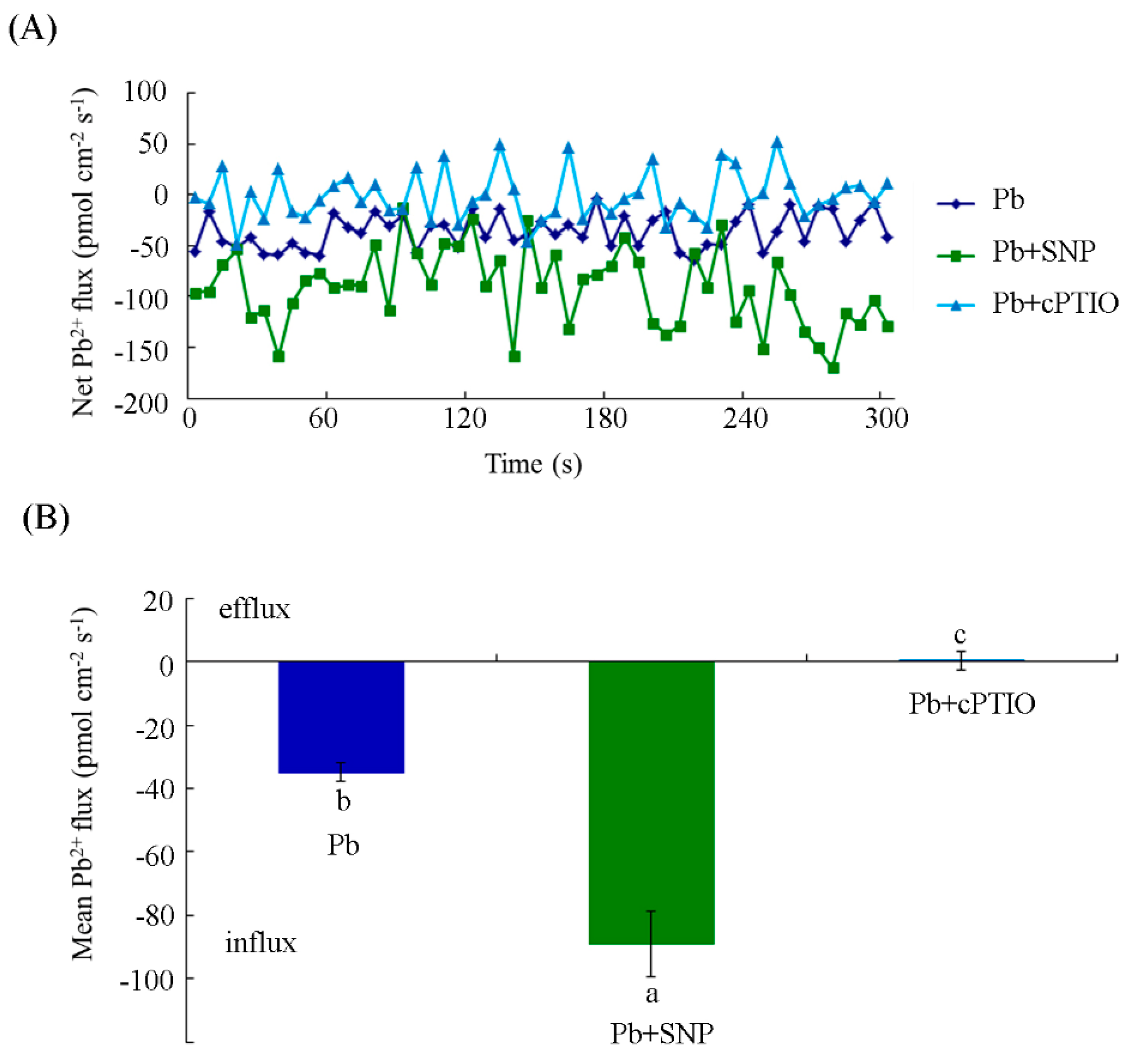

2.4. NO Increased Pb2+ Influx in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

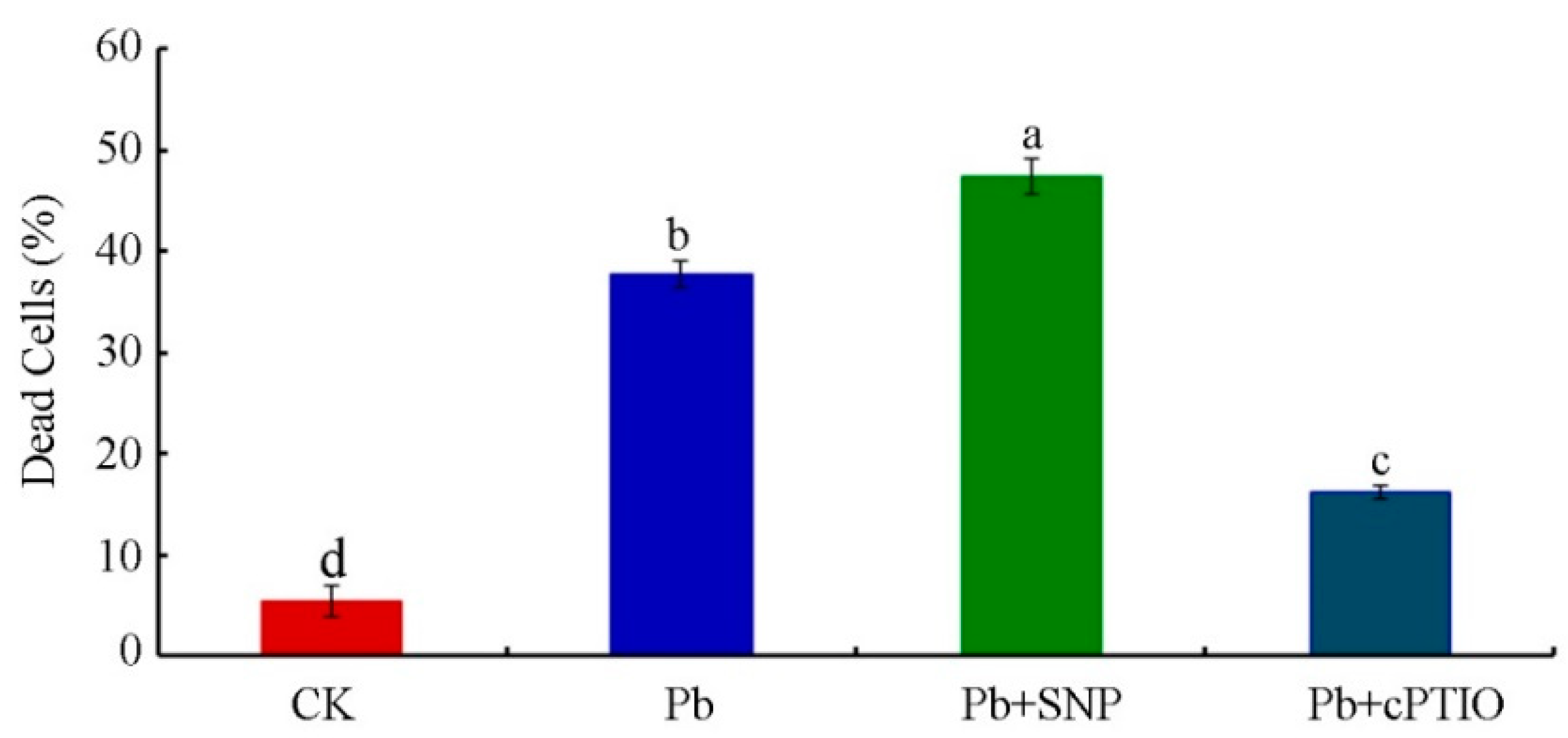

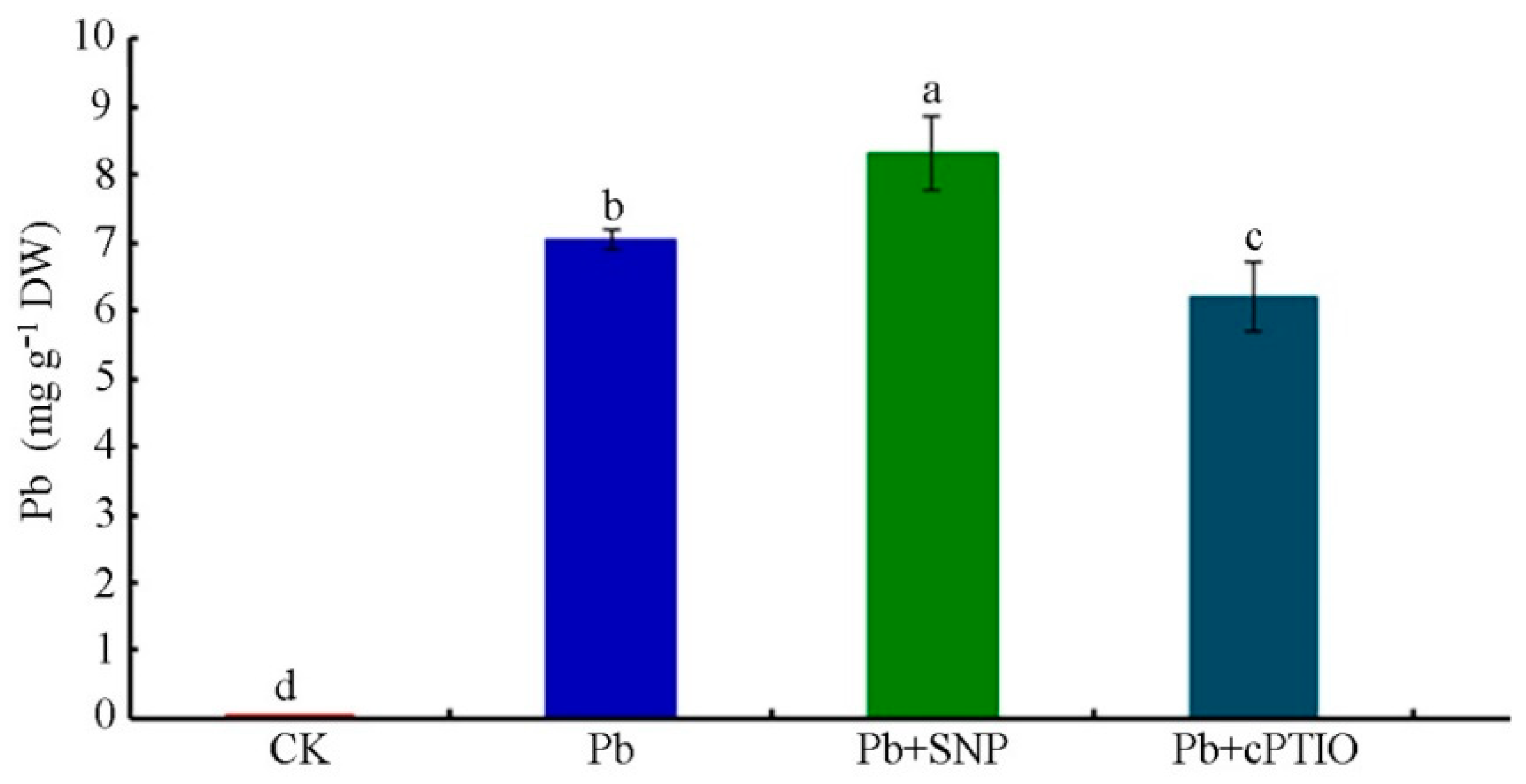

2.5. NO Promoted Pb Uptake to Aggravate Pb Toxicity

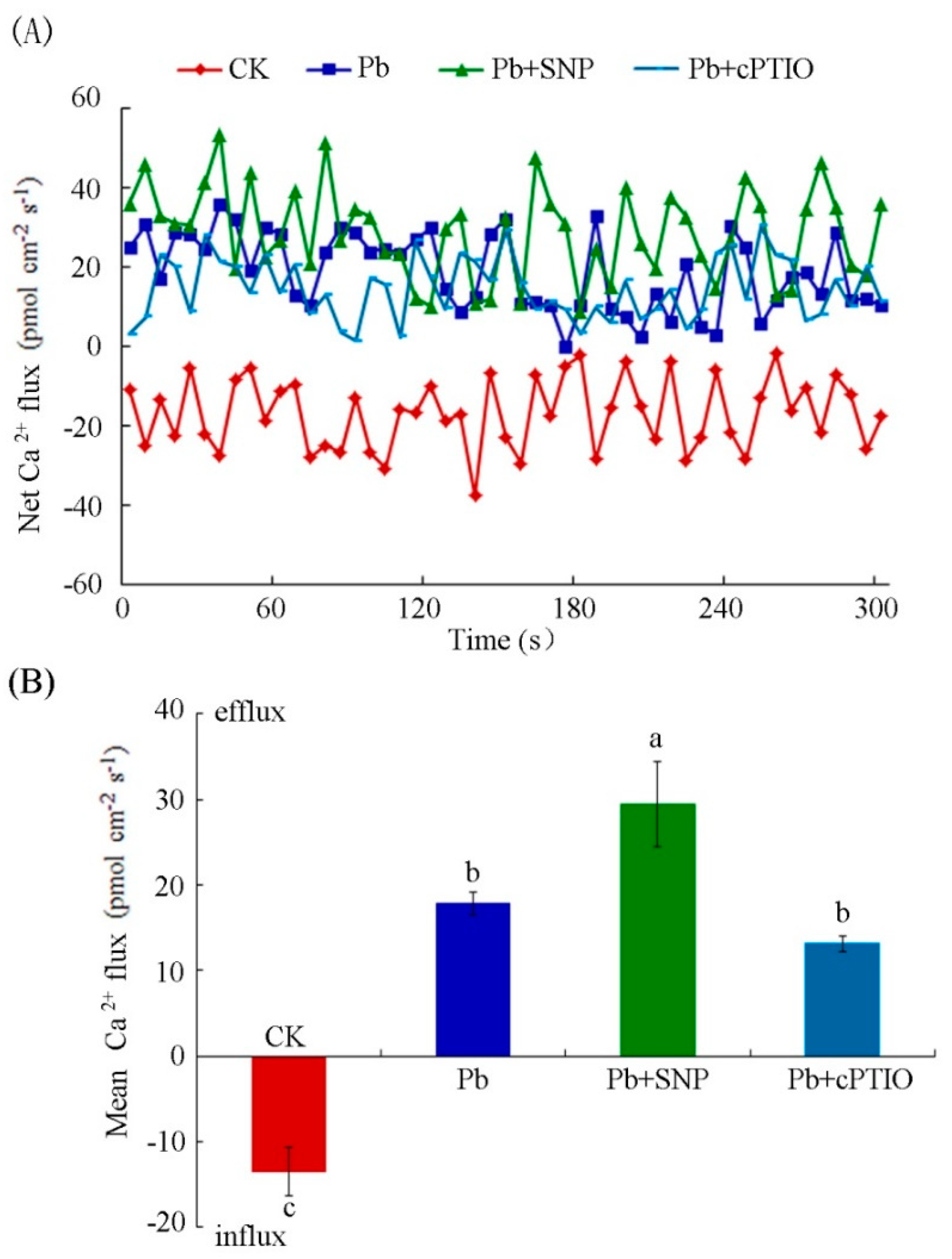

2.6. NO Enhanced Pb-Induced Calcium Homeostasis Disorder

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Hoechst and PI Double Staining

4.3. Detection of NO and ROS Production

4.4. Determination of Pb Content

4.5. Measurement of Pb2+ and Ca2+ Fluxes

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malizia, D.; Giuliano, A.; Ortaggi, G.; Masotti, A. Common plants as alternative analytical tools to monitor heavy metals in soil. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesmar-Mn, J.K. The toxic effect of lead on seed germination, growth, chlorophyll and protein contents of wheat and lens. Acta Biol. Hung. 1991, 42, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zou, J.; Meng, Q.; Zou, J.; Jiang, W. Uptake and accumulation and oxidative stress in garlic (Allium sativum L.) under lead phytotoxicity. Ecotoxicology 2009, 18, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhevnikova, A.D.; Seregin, I.V.; Bystrova, E.I.; Belyaeva, A.I.; Kataeva, M.N.; Ivanov, V.B. The effects of lead, nickel, and strontium nitrates on cell division and elongation in maize roots. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 56, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nareshkumar, A.; Krishnappa, B.V.; Kirankumar, T.V.; Kiranmai, K.; Lokesh, U.; Sudhakarbabu, O.; Sudhakar, C. Effect of Pb-stress on growth and mineral status of two groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivars. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 2, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, D.; Nicoloso, F.; Schetinger, M.; Rossato, L.; Pereira, L.; Castro, G.; Srivastava, S.; Tripathi, R. Antioxidant defense mechanism in hydroponically grown Zea mays seedlings under moderate lead stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Q.; Hong, F.S. Effects of Pb2+ on the structure and function of photosystem II of Spirodela polyrrhiza. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2009, 129, 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.L.; Huang, H.J. ROS and CDPK-like kinase-mediated activation of MAP kinase in rice roots exposed to lead. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpas, F.J.; Barroso, J.B. Lead-Induced stress, which triggers the production of nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide anion (O2−) in Arabidopsis peroxisomes, affects catalase activity. Nitric Oxide 2017, 68, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laspina, N.V.; Groppa, M.D.; Tomaro, M.L.; Benavides, M.P. Nitric oxide protects sunflower leaves against Cd-induced oxidative stress. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Sun, L.; Jin, H.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Z.; Xu, M. Lead-induced nitric oxide generation plays a critical role in lead uptake by Pogonatherum crinitum root cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ries, A.; Wu, K.; Yang, A.; Crawford, N.M. The Arabidopsis prohibitin gene phb3 functions in nitric oxide–mediated responses and in hydrogen peroxide–induced nitric oxide accumulation. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.J.; Dong, J.F.; Zhang, X.B. Signal interaction between nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide in heat shock-induced hypericin production of Hypericum perforatum suspension cells. Sci. China Ser. C Life Sci. 2008, 51, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, S.; Gupta, M. An update on nitric oxide and its benign role in plant responses under metal stress. Nitric Oxide 2017, 67, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.; Durner, J.; Navarre, D.A.; Klessig, D.F. Nitric oxide inhibition of tobacco catalase and ascorbate peroxidase. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 2000, 13, 1380–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgia, I.; Tarantino, D.; Vannini, C.; Bracale, M.; Carravieri, S.; Soave, C. Arabidopsis thaliana plants overexpressing thylakoidal ascorbate peroxidase show increased resistance to paraquat-induced photooxidative stress and to nitric oxide-induced cell death. Plant J. 2004, 38, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Michele, R.; Vurro, E.; Rigo, C.; Costa, A.; Elviri, L.; Di-Valentin, M.; Careri, M.; Zottini, M.; Sanita-di-Toppi, L.; Schiavo, F.L. Nitric oxide is involved in cadmium induced programmed cell death in Arabidopsis suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groß, F.; Durner, J.; Gaupels, F. Nitric oxide, antioxidants and prooxidants in plant defence responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; He, L.; Gu, M. The diversity of nitric oxide function in plant responses to metal stress. Biometals 2014, 27, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrón-Camero, L.C.; Peláez-Vico, M.; Del-Val, C.; Sandalio, L.M.; Romero-Puertas, M.C. Role of nitric oxide in plant responses to heavy metal stress: Exogenous application versus endogenous production. J. Exp. Bot. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lu, H.; Lu, K.; Duan, Y.; An, L.; Zhu, C. Cadmium decreases crown root numbers by decreasing endogenous nitric oxide, which is indispensable for crown root primordial initiation in rice seedlings. Planta 2009, 230, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R.; Mahajan, P.; Kohli, R.K.; Rishi, V. Exogenous nitric oxide (NO) interferes with lead (Pb)-induced toxicity by detoxifying reactive oxygen species in hydroponically grown wheat (Triticum aestivum) roots. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Xu, W.; Xu, H.; Chen, Y.; He, Z.; Ma, M. Nitric oxide modulates cadmium influx during cadmium-induced programmed cell death in tobacco BY-2 cells. Planta 2010, 232, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, K.; Mehta, S.K.; Shekhawat, G.S. Nitric oxide (NO) counteracts cadmium induced cytotoxic processes mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) in Brassica juncea: Cross-Talk between ROS, NO and antioxidant responses. Biometals 2013, 26, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.R.; Hwang, S. Over-expression of NtHb1 encoding a non-symbiotic class 1 hemoglobin of tobacco enhances a tolerance to cadmium by decreasing NO (nitric oxide) and Cd levels in Nicotiana Tabacum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 113, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson-Bard, A.; Gravot, A.; Richaud, P.; Auroy, P.; Duc, C.; Gaymard, F.; Taconnat, L.; Renou, J.P.; Pugin, A.; Wendehenne, D. Nitric oxide contributes to cadmium toxicity in Arabidopsis by promoting cadmium accumulation in roots and by up-regulating genes related to iron uptake. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Interplay among nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species a complex network determining cell survival or death. Plant Signal. Behav. 2007, 2, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrowska, E.; Różalska, S.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Nawrocka, J.; Małolepsza, U. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen (ROS and RNS) species generation and cell death in tomato suspension cultures-Botrytis cinerea interaction. Protoplasma 2015, 252, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.F.; Zhang, W.S.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.N.; Li, K.X.; Han, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Li, X. An endoplasmic reticulum response pathway mediates programmed cell death of root tip induced by water stress in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. Trust 2010, 186, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Huang, G.; Yu, J.; Zhang, M.; Shi, X. Nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide are involved in indole-3-butyric acid-induced adventitious root development in marigold. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 2011, 86, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, H.K.; Butt, Y.K.; Lo, S.C. Hydrogen peroxide induces a rapid production of nitric oxide in mung bean (Phaseolus aureus). Nitric Oxide 2002, 6, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.Z.; Yu, S.Y.; Peijnenburg, W.J.; Luo, Y.M. Determining the fluxes of ions (Pb2+, Cu2+ and Cd2+) at the root surface of wetland plants using the scanning ion-selective electrode technique. Plant Soil 2017, 414, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLamore, E.S.; Porterfield, D.M.; Banks, M.K. Non-invasive self-referencing electrochemical sensors for quantifying real-time biofilm analyte flux. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 102, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmat, R.; Haider, S.; Riaz, M. An inverse relation between Pb2+ and Ca2+ ions accumulation in phaseolus mungo and lens culinaris under Pb stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 2289–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Pourrut, B.; Dumat, C.; Nadeem, M.; Aslam, M.; Pinelli, E. Heavy-metal-induced reactive oxygen species: Phytotoxicity and physicochemical changes in plants. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 232, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Pinelli, E.; Pourrut, B.; Silvestre, J.; Dumat, C. Lead-induced genotoxicity to Vicia faba L. roots in relation with metal cell uptake and initial speciation. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2011, 74, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, P.; Rekhadevi, P.V.; Danadevi, K.; Vuyyuri, S.B.; Mahboob, M.; Rahman, M.F. Genotoxicity evaluation in workers occupationally exposed to lead. Int. J. Hyg. Envirn. Health 2010, 213, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Nicoloso, F.T.; Schetinger, M.R.; Rossato, L.V.; Huang, H.G.; Srivastava, S.; Yang, X.E. Lead induced responses of Pfaffia glomerata, an economically important Brazilian medicinal plant, under in vitro culture conditions. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 86, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M.; Asher, C.J.; Blamey, F.P.C.; Menzies, N.W. Toxic effects of Pb2+ on the growth and mineral nutrition of signal grass (Brachiaria decumbens) and Rhodes grass (Chloris gayana). Plant Soil 2007, 300, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourato, M.; Moreira, I.; Leitão, I.; Pinto, F.; Sales, J.; Martins, L. Effect of heavy metals in plants of the genus Brassica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17975–17998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, A.; Posmyk, M.M. Melatonin restricts Pb-induced PCD by enhancing BI-1 expression in tobacco suspension cells. Biometals 2016, 29, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.M.; Kumar, S.G.; Jyothsnakumari, G.; Thimmanaik, S.; Sudhakar, C. Lead induced changes in antioxidant metabolism of horsegram (Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.) and bengalgram (Cicer arietinum L.). Chemosphere 2005, 60, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Dubey, R.S. Lead toxicity induces lipid peroxidation and alters the activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice plants. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Kaur, S.; Batish, D.R.; Sharma, V.P.; Sharma, N.; Kohli, R.K. Nitric oxide alleviates arsenic toxicity by reducing oxidative damage in the roots of Oryza sativa (rice). Nitric Oxide 2009, 20, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.C.; Hung, K.T.; Kao, C.H. Nitric oxide reduces Cu toxicity and Cu-induced NH4+ accumulation in rice leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 162, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R.; Kaur, G.; Arora, K.; Kohli, R.K. Nitric oxide (as sodium nitroprusside) supplementation ameliorates Cd toxicity in hydroponically grown wheat roots. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindermayr, C.; Durner, J. Interplay of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide: Nitric oxide coordinates reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yin, H.X.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, X.J. Nitric oxide is associated with long-term zinc tolerance in Solanum nigrum. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1319–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, D.; Jain, P.; Singh, N.; Kaur, H.; Bhatla, S.C. Mechanisms of nitric oxide crosstalk with reactive oxygen species scavenging enzymes during abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Free Radic. Res. 2016, 50, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Macovei, A.; Tuteja, N. Importance of nitric oxide in cadmium stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 63, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pető, A.; Lehotai, N.; Feigl, G.; Tugyi, N.; Ördög, A.; Gémes, K.; Tari, I.; Erdei, L.; Kolbert, Z. Nitric oxide contributes to copper tolerance by influencing ROS metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghipour, O. Pretreatment with nitric oxide reduces lead toxicity in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L.] walp.). Arch. Biol. Sci. 2016, 68, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cao, H.; Yang, L.; Chen, C.; Shabala, L.; Xiong, M.; Niu, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, L.; et al. Tissue-specific respiratory burst oxidase homologue-dependent H2O2 signaling to the plasma membrane H+-ATPase confers potassium uptake and salinity tolerance in Cucurbitaceae. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, erz328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.F.; Du, B.S.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, Y.; Cao, Q.Q.; Qin, L. Boron deficiency alters cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and affects the cell wall components of pollen tubes in Malus domestica. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamhamdi, M.; El-Galiou, O.; Bakrim, A.; Nóvoa-Muñoz, J.C.; Arias-Estevez, M.; Aarab, A.; Lafont, R. Effect of lead stress on mineral content and growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea) seedlings. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 20, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fan, C.; Liu, K.; Jing, Y. Extracellular ATP is involved in the initiation of pollen germination and tube growth in Picea meyeri. Trees 2015, 29, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, R.; Cao, Y.; Shan, X.; Jing, Y. Nitric Oxide Enhances Cytotoxicity of Lead by Modulating the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Is Involved in the Regulation of Pb2+ and Ca2+ Fluxes in Tobacco BY-2 Cells. Plants 2019, 8, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8100403

Wu J, Zhang Y, Hao R, Cao Y, Shan X, Jing Y. Nitric Oxide Enhances Cytotoxicity of Lead by Modulating the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Is Involved in the Regulation of Pb2+ and Ca2+ Fluxes in Tobacco BY-2 Cells. Plants. 2019; 8(10):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8100403

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jiaye, Yue Zhang, Ruizhi Hao, Yuan Cao, Xiaoyi Shan, and Yanping Jing. 2019. "Nitric Oxide Enhances Cytotoxicity of Lead by Modulating the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Is Involved in the Regulation of Pb2+ and Ca2+ Fluxes in Tobacco BY-2 Cells" Plants 8, no. 10: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8100403

APA StyleWu, J., Zhang, Y., Hao, R., Cao, Y., Shan, X., & Jing, Y. (2019). Nitric Oxide Enhances Cytotoxicity of Lead by Modulating the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Is Involved in the Regulation of Pb2+ and Ca2+ Fluxes in Tobacco BY-2 Cells. Plants, 8(10), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8100403