Hormonal Regulation and Expression Profiles of Wheat Genes Involved during Phytic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

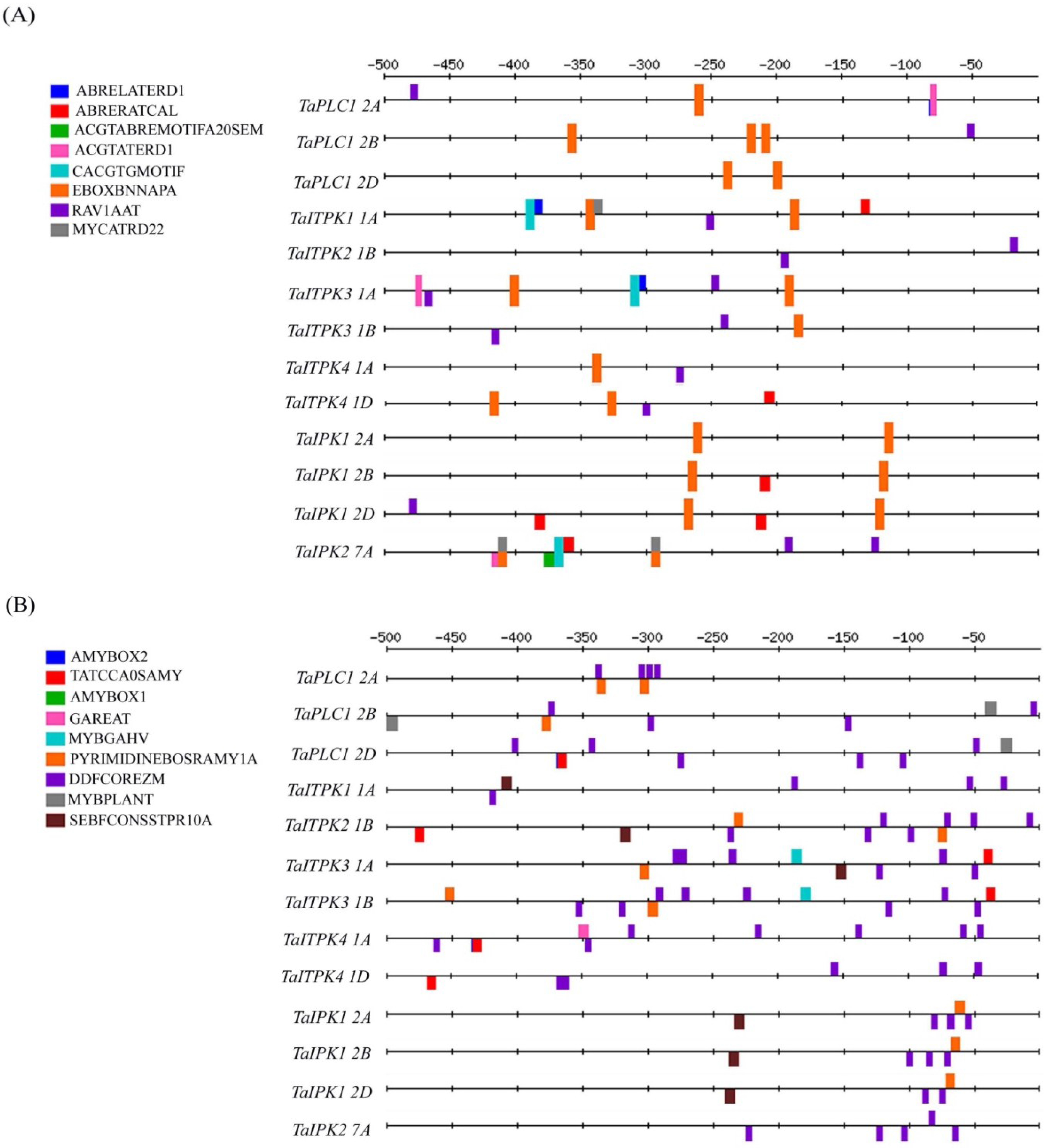

2.1. In-Silico Analysis of the Regulatory Cis-Elements

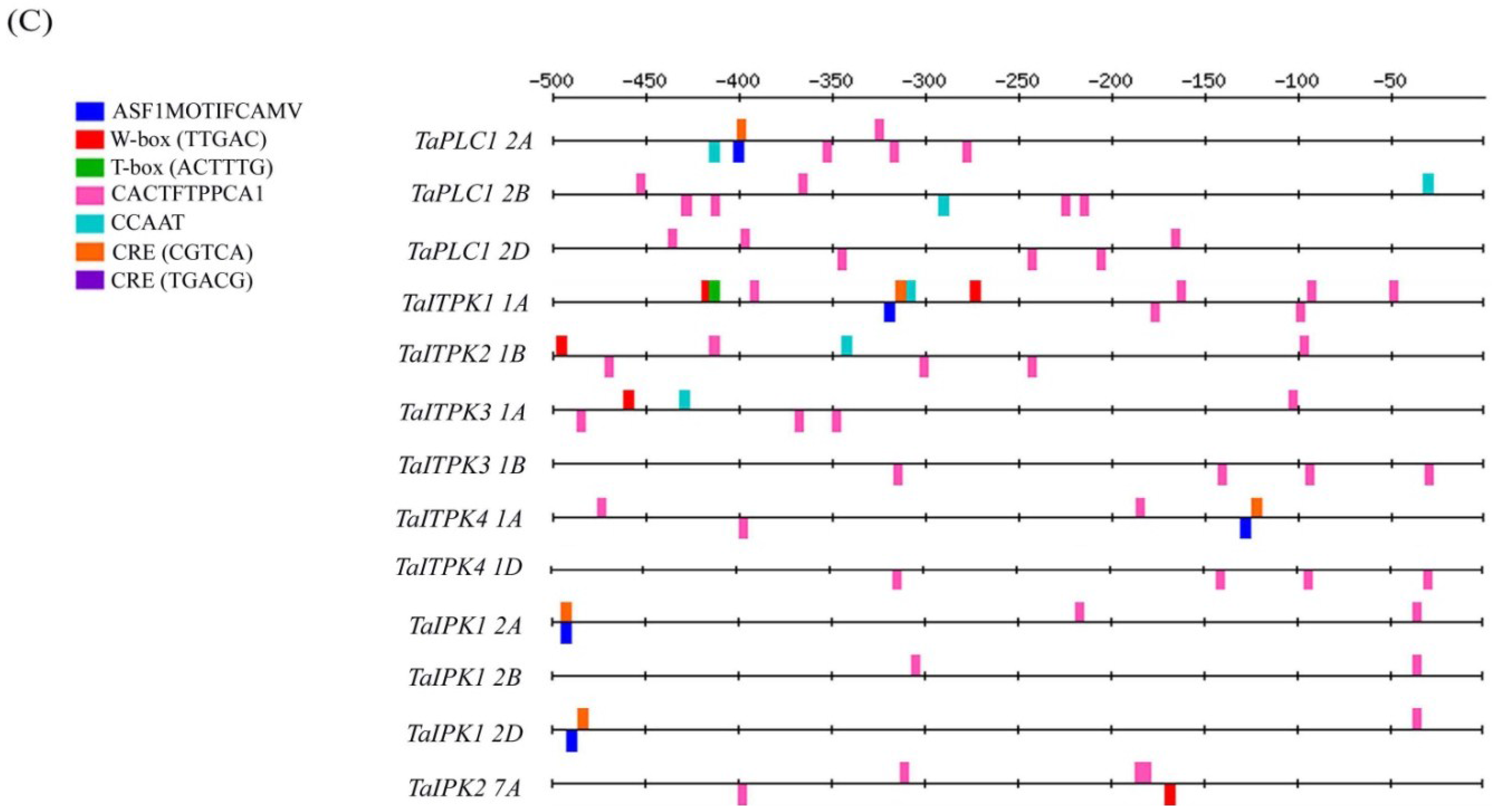

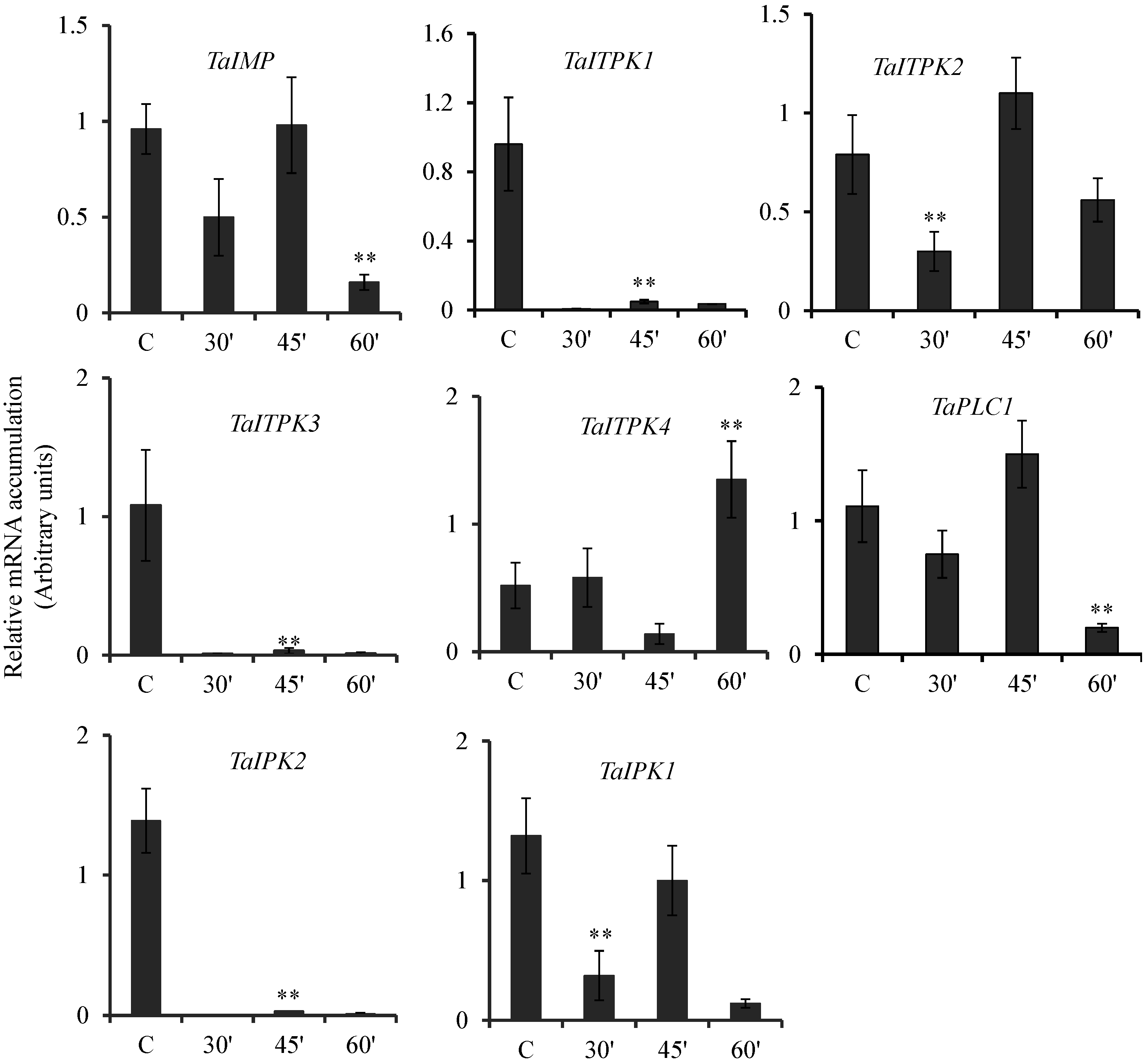

2.2. Hormonal Regulation of PA Pathway Genes

2.3. Expression Pattern of PA Pathway Genes in Presence of SA and cAMP

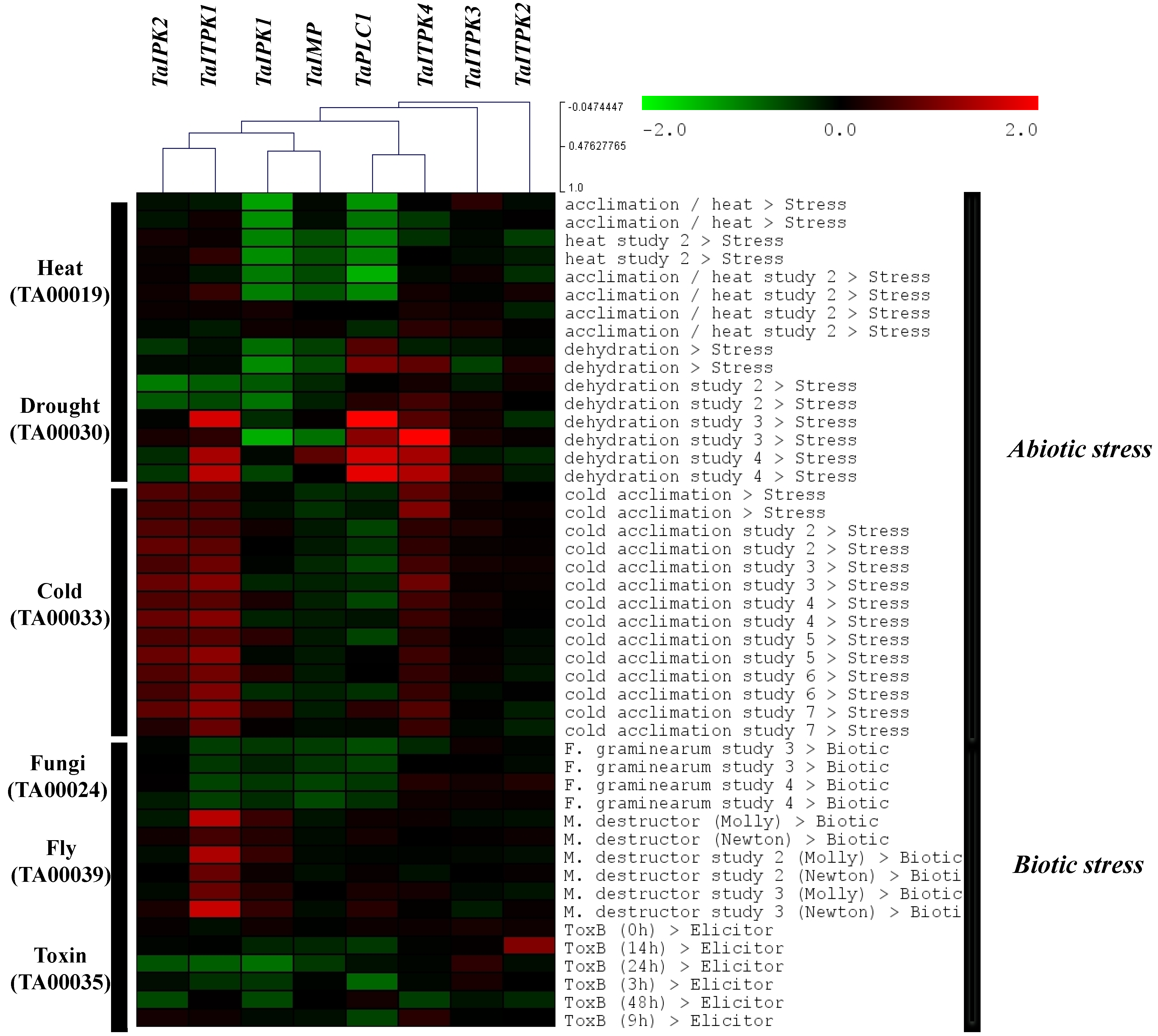

2.4. Expression Profile Analysis of Genes during Other Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Exogenous Treatment of Seeds with Hormones

4.3. RNA Isolation from Plant Materials and Quantitative Real Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.4. In-Silico Analysis of Cis-Element Search in Upstream Region of Wheat Genes

4.5. GENEVESTIGATOR Analysis of PA Pathway Genes

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| cis elements | TaPLC1 | TaITPK1 | TaITPK2 | TaITPK3 | TaITPK4 | TaIPK2 | TaIPK1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2A | 2B | 2D | 1A | 1B | 1A* | 1B | 1A* | 1D* | 7A* | 2A | 2B | 2D | ||

| ABA RESPONSE ELEMENTS | ||||||||||||||

| ABRELATERD1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| ABRERATCAL | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| ACGTABREMOTIFA2OSEM | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ACGTATERD1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| CACGTGMOTIF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| EBOXBNNAPA | 6 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 12 | |

| RAV1AAT | 5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| MYCATRD22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| GA RESPONSE ELEMENTS | ||||||||||||||

| AMYBOX2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TATCCAOSAMY | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMYBOX1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| GAREAT | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| MYBGAHV | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| PYRIMIDINEBOXOSRAMY1A | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| DOFCOREZM | 9 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 17 | 12 | 13 | 17 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | |

| MYBPLANT | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| SEBFCONSSTPR10A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| SA RESPONSE ELEMENTS | ||||||||||||||

| ASF1MOTIFCAMV | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| W-box (TTGAC) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| T-box (ACTTTG) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| CACTFTPPCA1 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | |

| CCAAT | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| cAMP RESPONSE ELEMENTS# | ||||||||||||||

| CRE (CGTCA) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| CRE (TGACG) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Name of Gene | Primers (5'–3') | Amplicon size (in bp) |

|---|---|---|

| TaITPK1 | Forward: ATGGTGGCCGAGCACCAGTCCTC Reverse: GACGACGGGCACGGAGGGGTGG | 261 |

| TaITPK2 | Forward: AGGAGTTCGTCAACCATGGCGGCGT Reverse: GCCGCCCGCGATCTGGTTGATGAAT | 247 |

| TaITPK3 | Forward: ACGCCATCGACCGCCTCCACAACC Reverse: CGGCGACGAGGGGCTTGGCGATGA | 222 |

| TaITPK4 | Forward: CAGCCTGCCGGACGTGCCGAC Reverse: ATGTCGAAGTTGAACAGCTGCA | 210 |

| TaPLCl | Forward: CGTGCTCCTATCAACAAAGCC Reverse : CTGTTCGTCCTCATCGTCGT | 317 |

| TaITPK2 | Forward: GCCCTACGTCACCAAGTGCCTCGC Reverse: AACCACGCCTTGAGCTCGCGCAGC | 283 |

| TaITPK1 | Forward: ACTGGGTCTACAAGGGAGAGGGC Reverse : ACACGAACCCCGCCATCAACATGA | 279 |

| TaLMP | Forward: GGACCACAAGTTCATCGGCGAGG Reverse: CTCCAACGGTGGGAATCTTCCC | 176 |

| Ta18SrRNA | Forward: GTGACGGGTGACGGAGAATT Reverse : GACACTAATGCGCCCGGTAT | 150 |

| TaAGP- S | Forward: GCAAGATACACCATTCAGTAGTTGGAC Reverse : GACTGTTCCACTAGGGAGTAAAGCATC | 326 |

| TaGBSS-I | Forward: CTCGCCGCCAACTACGACGTC Reverse : TGCTCGGGAACTTCTCCTCCAC | 268 |

| TaBMY | Forward: CTAGCCAACTATGTCCAAGTCTACGT Reverse : ACTGTGGGATGGGGATGTTGACGA | 370 |

| TaSP-H | Forward: TGGCCAGCAAAAAGCGCCTAGC Reverse : TCTGCCTGTCTGCTGCGCTCA | 183 |

| Query gene | Target Probe set ID | e-value | Identity (%) | Query length | Query range | Target length | Target range | Target description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaITPK1 | Ta.27561.1.S1_at | 0.0 | 97.2 | 1038 | 25..938 | 1219 | 120..1036 | gb|CK215630 |

| TaITPK2 | TaAffx.113052.1.S1_at | 9e-52 | 86.2 | 876 | 533..770 | 549 | 139..377 | gb|CA618510 |

| TaITPK3 | TaAffx.19998.1.A1_at | 0.0 | 97.5 | 1057 | 490..1057 | 1696 | 616..1184 | gb|CD867474 |

| TaITPK3 | TaAffx.19998.1.A1_at | 1e-151 | 97.0 | 1057 | 134..431 | 1696 | 1243..1540 | gb|CD867474 |

| TaITPK3 | TaAffx.19998.1.A1_at | 1e-29 | 100.0 | 1057 | 49..114 | 1696 | 1560..1625 | gb|CD867474 |

| TaITPK4 | TaAffx.121326.1.S1_at | 0.0 | 99.0 | 1018 | 6..606 | 722 | 64..667 | gb|CA690518 |

| TaITPK4 | Ta.27561.1.S1_x_at | 3e-58 | 84.4 | 1018 | 54..342 | 1219 | 134..422 | gb|CK215630 |

| TaPLC1 | Ta.13185.2.A1_at | 1e-46 | 86.5 | 1876 | 1541..1750 | 224 | 1..204 | gb|BJ214989 |

| TaIPK2 | Ta.30464.1.A1_at | 1e-133 | 100.0 | 899 | 1-240 | 858 | 291-530 | gb|CK214494 |

| TaIPK2 | Ta.30464.1.A1_at | 1e-117 | 100.0 | 899 | 306-517 | 858 | 14-225 | gb|CK214494 |

| TaIPK1 | TaAffx.123037.2.S1_at | 0.0 | 96.4 | 1125 | 28-1125 | 1502 | 198-1297 | gb|CA613702 |

| TaIMP | Ta.14044.1.S1_at | 0.0 | 97.5 | 983 | 1..893 | 1085 | 90..982 | gb|BT009424 |

| Query gene | IWGSC ID | NCBI ID |

|---|---|---|

| TaITPK1-2A | IWGSC_1AL_v2|IWGSC_chr1AL_v2_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_3977071 | |

| TaITPK21B | IWGSC_1BL|IWGSC_chr1BL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_3850458 | |

| TaITPK3-1A* | - | gb|KD008473.1 |

| TaITPK3-1B | IWGSC_1BL|IWGSC_chr1BL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_5693968 | |

| TaITPK4-1A* | - | gb|KD262384.1 |

| TaITPK4-1D* | - | gb|KD502010.1 |

| TaPLC1-2A | IWGSC_2AL|IWGSC_chr2AL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_6422019 | |

| TaPLC1-2B | IWGSC_2BL|IWGSC_chr2BL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_7936983 | |

| TaPLC1-2D | IWGSC_2DL|IWGSC_chr2DL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_9907826 | |

| TaIPK2-7A* | - | gb|KD115052.1 |

| TaIPK1-2A | IWGSC_2AL|IWGSC_chr2AL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_6422019 | |

| TaIPK1-2B | IWGSC_2BL|IWGSC_chr2BL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_7936983 | |

| TaIPK1-2D | IWGSC_2DL|IWGSC_chr2DL_ab_k71_contigs_longerthan_200_9907826 |

References

- Dean, C.; Schmidt, R. Plant genomes a current description. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995, 46, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y.; Ichida, H.; Matsui, M.; Obokata, J.; Sakurai, T.; Satou, M.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Abe, T. Identification of plant promoter constituents by analysis of local distribution of short sequences. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 1471–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewley, J.D. Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, F.; Cejudo, F.J. Programmed cell death (PCD): An essential process of cereal seed development and germination. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.G. The Role of Phytic Acid in the Wheat Grain. Plant Physiol. 1970, 45, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhati, K.K.; Aggarwal, S.; Sharma, S.; Mantri, S.; Singh, S.P.; Bhalla, S.; Kaur, J.; Tiwari, S.; Roy, J.K.; Tuli, R.; et al. Differential expression of structural genes for the late phase of phytic acid biosynthesis in developing seeds of wheat (Triticumaestivum L.). Plant Sci. 2014, 224, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudencia-Chingcuanco, D.L.; Stamova, B.S.; You, F.M.; Lazo, G.R.; Beckles, D.M.; Anderson, O.D. Transcriptional profiling of wheat caryopsis development using cDNA microarrays. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 63, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fincher, G.B. Molecular and cellular biology associated with endosperm mobilization in germinating cereal grains. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989, 40, 305–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Jacobsen, J.V. Regulation of the synthesis and transport of secreted proteins in cereal aleurone. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1991, 126, 49–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, C.N.; Proebsting, W.M.; Hedden, P.; Rivin, C.J. Gibberellins and Seed Development in Maize. I. Evidence That Gibberellin/Abscisic Acid Balance Governs Germination versus Maturation Pathways. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethke, P.C.; Hwang, Y.S.; Zhu, T.; Jones, R.L. Global patterns of gene expression in the aleurone of wild-type and dwarf1 mutant rice. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, N.; Liu, R.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J. H2O2 mediates the regulation of ABA catabolism and GA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seed dormancy and germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 2979–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taji, T.; Takahashi, S.; Shinozaki, K. Inositols and their metabolites in abiotic and biotic stress responses. Subcell. Biochem. 2006, 39, 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno, K.; Fujimura, T. Induction of phytic acid synthesis by abscisic acid in suspension-cultured cells of rice. Plant Sci. 2014, 217–218, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, S.A.; Futardo, A.; Henry, R.J. Gene expression in the developing aleurone and starchy endosperm of wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 10, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raboy, V. Approaches and challenges to engineering seed phytate and total phosphorus. Plant Sci. 2009, 79, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson-Paulik, J.; Bastidas, R.J.; Chiou, S.T.; Frye, R.A.; York, J.D. Generation of phytate free seeds in Arabidopsis through disruption of inositol polyphosphate kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12612–12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.K.; Ingvardsen, C.R.; Torp, A.M. Mutations in genes controlling the biosynthesis and accumulation of inositol phosphates in seeds. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, A.R.; Qian, X.; Shears, S.B.; Grabau, E.A. Metabolic and signaling properties of an Itpk gene family in Glycine max. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1853–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzeri, D.; Cassani, E.; Doria, E.; Tagliabue, G.; Forti, L.; Campion, B.; Bollini, R.; Brearley, C.A.; Pilu, R.; Nielsen, E.; et al. A defective ABC transporter of the MRP family, responsible for the bean lpa1 mutation, affects the regulation of the phytic acid pathway, reduces seed myo-inositol and alters ABA sensitivity. New Phytol. 2011, 191, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raboy, V. Seeds for a better future: “Low phytate” grains help to overcome malnutrition and reduce pollution. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 6, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboy, V. The ABCs of low-phytate crops. Nat Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 874–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, K.; Kuwano, M.; Yoshida, K.T. Expression pattern of inositolphosphate-related enzymes in rice (Oryzasativa L.): Implications for the phytic acid biosynthetic pathway. Gene 2007, 405, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, L.; Leckie, C.P.; Aitken, F.L.; Wentworth, M.; McAinsh, M.R.; Gray, J.E.; Hetherington, A.M. The effects of manipulating phospholipase C on guard cell ABA-signalling. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 55, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- De-Jong, C.F.; Laxalt, A.M.; Bargmann, B.O.; de Wit, P.J.; Joosten, M.H.; Munnik, T. Phosphatidic acid accumulation is an early response in the Cf-4/Avr4 interaction. Plant J. 2004, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, I.Y.; Heilmann, I.; Chang, S.C.; Boss, W.F.; Kaufman, P.B. A role for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate in gravitropicsignaling and the retention of cold-perceived gravistimulation of oat shoot pulvini. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charron, D.; Pingret, J.L.; Chabaud, M.; Journet, E.P.; Barker, D.G. Pharmacological evidence that multiple phospholipid signaling pathways link rhizobium nodulation factor perception in Medicagotruncatula root hairs to intracellular responses, including Ca2+ spiking and specific ENOD gene expression. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3582–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartog, M.D.; Verhoef, N.; Munnik, T. Nod factors and elicitors activate different phospholipid signalling pathways in suspension cultured alfalfa cells. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, T.; Ritchie, S.; Assmann, S.M.; Gilroy, S. Abscisic acid signal transduction in guard cells is mediated by phospholipase D activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 9, 12192–12197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetman, D.; Stavridou, I.; Johnson, S.; Green, P.; Caddick, S.E.; Brearley, C.A. Arabidopsis thaliana inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase 4 (AtITPK4) is an outlier to a family of ATP-grasp fold proteins from Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4165–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefsen, L.; Bohn, L.; Sørensen, M.B.; Rasmussen, S.K. Characterization of a multifunctional inositol phosphate kinase from rice and barley belonging to the ATP-grasp superfamily. Gene 2007, 397, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Hazebroek, J.; Meeley, R.B.; Ertl, D.S. The maize low-phytic acid mutant lpa2 is caused by mutation in an inositol phosphate kinase gene. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson-Paulik, J.; Odom, A.R.; York, J.D. Molecular and biochemical characterization of two plant inositol polyphosphate 6-/3-/5-kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42711–42718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweetman, D.; Johnson, S.; Caddick, S.E.; Hanke, D.E.; Brearley, C.A. Characterization of an Arabidopsis inositol 1,3,4,5,6-pentakisphosphate 2-kinase (AtIPK1). Biochem. J. 2006, 394, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khurana, N.; Chauhan, H.; Khurana, P. Expression analysis of a heat-inducible, Myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase (MIPS) gene from wheat and the alternatively spliced variants of rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 237–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruelland, E.; Pokotylo, I.; Djafi, N.; Cantrel, C.; Repellin, A.; Zachowski, A. Salicylic acid modulates levels of phosphoinositide dependent-phospholipase C substrates and products to remodel the Arabidopsis suspension cell transcriptome. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkart-Waco, D.; Ngo, K.; Dilkes, B.; Josefsson, C.; Comai, L. Early disruption of maternal-zygotic interaction and activation of defense-like responses in arabidopsis interspecific crosses. Plant Cell 2013, 6, 2037–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-T.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Pan, Q.-H.; Yang, H.-R.; Zhan, J.-C.; Huang, W.-D. Novel interrelationship between salicylic acid, abscisic acid, and PIP2-specific phospholipase C in heat acclimation-induced thermotolerance in pea leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 12, 3337–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-T.; Huang, W.-D.; Pan, Q.-H.; Weng, F.-H.; Zhan, J.-C.; Liu, Y.; Wan, S.-B.; Liu, Y.-Y. Contributions of PIP2-specificphospholipase C and free salicylic acid to heat acclimation-induced thermotolerance in pea leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, C.J. Influence of gibbrellic acid on the incorporation of 8–14C adenine adenosine 3',5'-cyclic phosphate in barley aleurone layers. Biochim. Biophys. 1970, 201, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, A.; Hussey, P.J.; Trewavas, A.J.; Malho, R. cAMP acts as a second messenger in pollen tube growth and reorientation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 18, 10481–10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Jin, C.; Wu, L.; Hou, M.; Dou, S. Expression analysis of a stress-related phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C gene in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Shukla, V.; Mantri, S.; Pandey, A.K. National Agri-Food Biotechnology Institute: Mohali, India, Unpublished data. 2015.

- Cutler, S.R.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Finkelstein, R.R.; Abrams, S.R. Abscisic acid: Emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 61, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendra, A.S.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Christmann, A.; Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, J.J.; Peterson, F.C.; Volkman, B.F.; Cutler, S.R. Structural and functional insights into core ABA signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Usha, K. Salicylic acid induced physiological and biochemical changes in wheat seedlings under water stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 39, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakirova, F.M.; Sakhabutdinova, A.R.; Bezrukova, M.V.; Fathutdinova, R.A.; Fathutdinova, D.R. Changes in hormonal status of wheat seedlings induced by salicylic acid and salinity. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Guo, H.; Sun, M. Signal transduction during wheat grain development. Planta 2015, 241, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, R.R.; Gampala, S.S.; Rock, C.D. Abscisic acid signaling in seeds andseedlings. Plant Cell 2002, 14, S15–S45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Villasuso, A.L.; Di-Palma, M.A.; Pasquaré, S.J.; Racagni, G.; Giusto, N.M.; Machado, E.E. Differences in phosphatidic acid signalling and metabolism between ABA and GA treatments of barley aleuronecells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 65, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Tan, S.; Xue, H. Arabidopsis inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6 kinase 2 is required for seed coat development. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2013, 45, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Liu, L.; You, L.; Yang, M.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Xiong, L. Characterization of an inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase gene that is essential for drought and salt stress responses in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 77, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Tang, R.; Zhu, J.; Liu, H.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Xia, H.; Zhang, H. Enhancement of stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants constitutively expressing AtIpk2β, an inositol polyphosphate 6-/3-kinase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 66, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villasuso, A.L.; Molas, M.L.; Racagni, G.; Abdala, G.; Machado-Domenech, E. Gibberellin signal in barley aleurone: Early activation of PLC by G protein mediates amylase secretion. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 41, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashem, M.A.; Itoh, K.; Iwabuchi, S.; Hori, H.; Mitsui, T. Possible involvement of phosphoinositide-Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of α-amylase expression and germination of rice seed (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Physiol. 2000, 41, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourbakhsh, A.; Collakova, E.; Gillaspy, G.E. Characterization of the inositol monophosphatase gene family in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, L.N.; Marineo, S.; Mandala, S.; Davids, F.; Sewell, B.T.; Ingle, R.A. The missing link in plant histidine biosynthesis: Arabidopsis myo-inositol monophosphatase-like2 encodes a functional histidinol-phosphate phosphatase. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.C.; Salvi, P.; Kaur, H.; Verma, P.; Petla, B.P.; Rao, V.; Kamble, N.; Majee, M. Differentially expressed myo-inositol monophosphatase gene (CaIMP) in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) encodes a lithium-sensitive phosphatase enzyme with broad substrate specificity and improves seed germination and seedling growth under abiotic stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5623–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dat, J.F.; Lopez-Delgado, H.; Foyer, C.H.; Scott, I.M. Parallel changes in H2O2 and catalase during thermotolerance induced by salicylic acid or heat acclimation in mustard seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1998, 116, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring, C. Adenylcyclases and cAMP in plant signaling-past and present. Cell Commun. Signal. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazaki, J.; Shimatani, Z.; Hashimoto, A.; Nagata, Y.; Fujii, F.; Kojima, K.; Suzuki, K.; Taya, T.; Tonouchi, M.; Nelson, C.; et al. Transcriptional profiling of genes responsive to abscisic acid and gibberellin in rice: Phenotyping and comparative analysis between rice and Arabidopsis. Physiol. Genomics 2004, 2, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.M.; Otto, B.; Brearley, C.A.; Carr, J.P.; Hanke, D.E. A role for inositol hexakisphosphate in the maintenance of basal resistance to plant pathogens. Plant J. 2008, 56, 638–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreenivasulu, N.; Radchuk, V.; Strickert, M.; Miersch, O.; Weschke, W.; Wobus, U. Gene expression patterns reveal tissue-specific signalling networks controlling programmed cell death and ABA-regulated maturation in developing barley grains. Plant J. 2006, 47, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, J.; Weier, D.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Strickert, M.; Weichert, N.; Melzer, M.; Czauderna, T.; Wobus, U.; Weber, H.; Weschke, W. Different hormonal regulation of cellular differentiation and function in nucellar projection and endosperm transfer cells: A microdissection-based transcriptome study of young barley grains. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitteng, L. Analysis of relative gene expression data using a real time quantitative PCR and 2-(Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparis, S.; Orczyk, W.; Zalewski, W.; Nadolska-Orczyk, A. The RNA-mediated silencing of one of the Pin genes in allohexaploid wheat simultaneously decreases the expression of the other, and increases grain hardness. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4025–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.; Hirsch-Hoffmann, M.; Hennig, L.; Gruissem, W. GENEVESTIGATOR. Arabidopsis microarray database and analysis toolbox. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2621–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Odom, D.T.; Koo, S.H.; Conkright, M.D.; Canettieri, G.; Best, J.; Chen, H.; Jenner, R.; Herbolsheimer, E.; Jacobsen, E.; Kadam, S.; Ecker, J.R.; Emerson, B.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Unterman, T.; Young, R.A.; Montminy, M. Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 22, 4459–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aggarwal, S.; Shukla, V.; Bhati, K.K.; Kaur, M.; Sharma, S.; Singh, A.; Mantri, S.; Pandey, A.K. Hormonal Regulation and Expression Profiles of Wheat Genes Involved during Phytic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway. Plants 2015, 4, 298-319. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants4020298

Aggarwal S, Shukla V, Bhati KK, Kaur M, Sharma S, Singh A, Mantri S, Pandey AK. Hormonal Regulation and Expression Profiles of Wheat Genes Involved during Phytic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway. Plants. 2015; 4(2):298-319. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants4020298

Chicago/Turabian StyleAggarwal, Sipla, Vishnu Shukla, Kaushal Kumar Bhati, Mandeep Kaur, Shivani Sharma, Anuradha Singh, Shrikant Mantri, and Ajay Kumar Pandey. 2015. "Hormonal Regulation and Expression Profiles of Wheat Genes Involved during Phytic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway" Plants 4, no. 2: 298-319. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants4020298

APA StyleAggarwal, S., Shukla, V., Bhati, K. K., Kaur, M., Sharma, S., Singh, A., Mantri, S., & Pandey, A. K. (2015). Hormonal Regulation and Expression Profiles of Wheat Genes Involved during Phytic Acid Biosynthesis Pathway. Plants, 4(2), 298-319. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants4020298