Differential Cadmium Responses in Two Salvia Species: Implications for Tolerance and Ecotoxicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

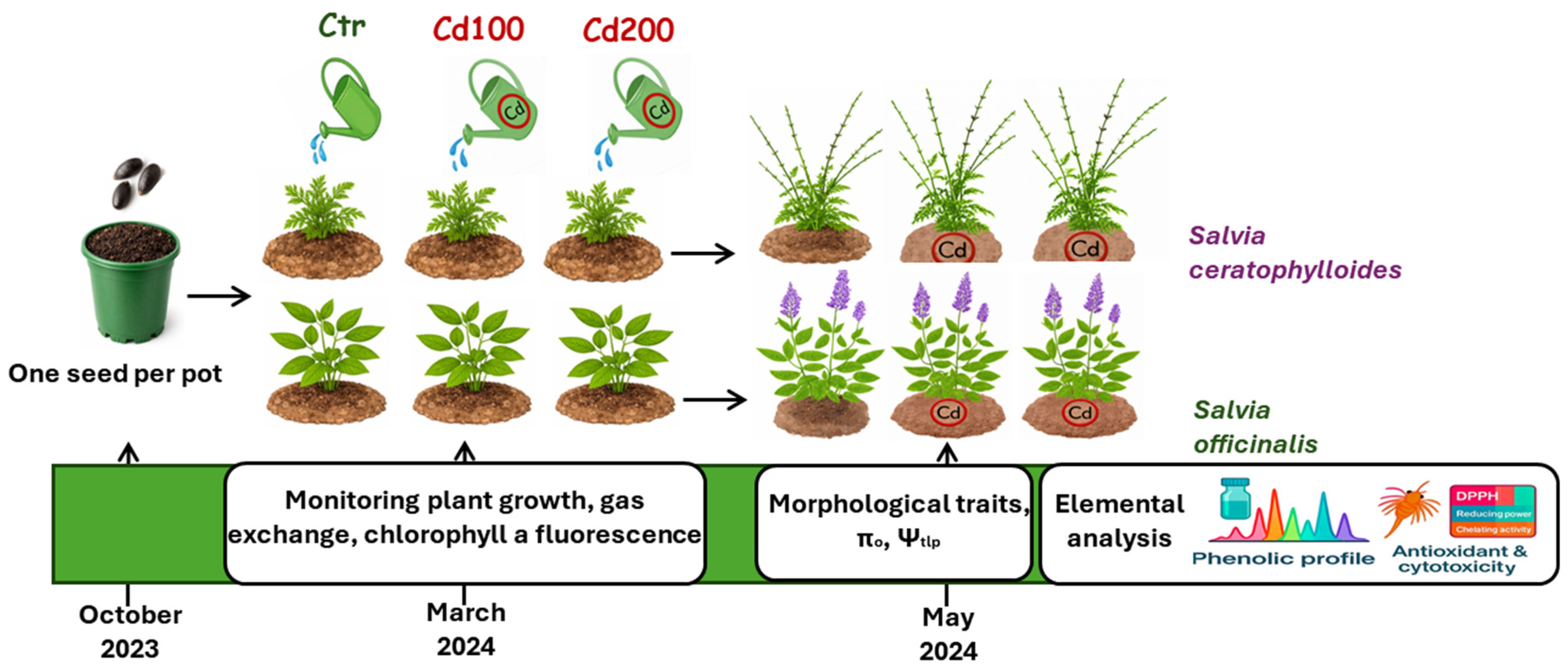

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Morphological Measurements

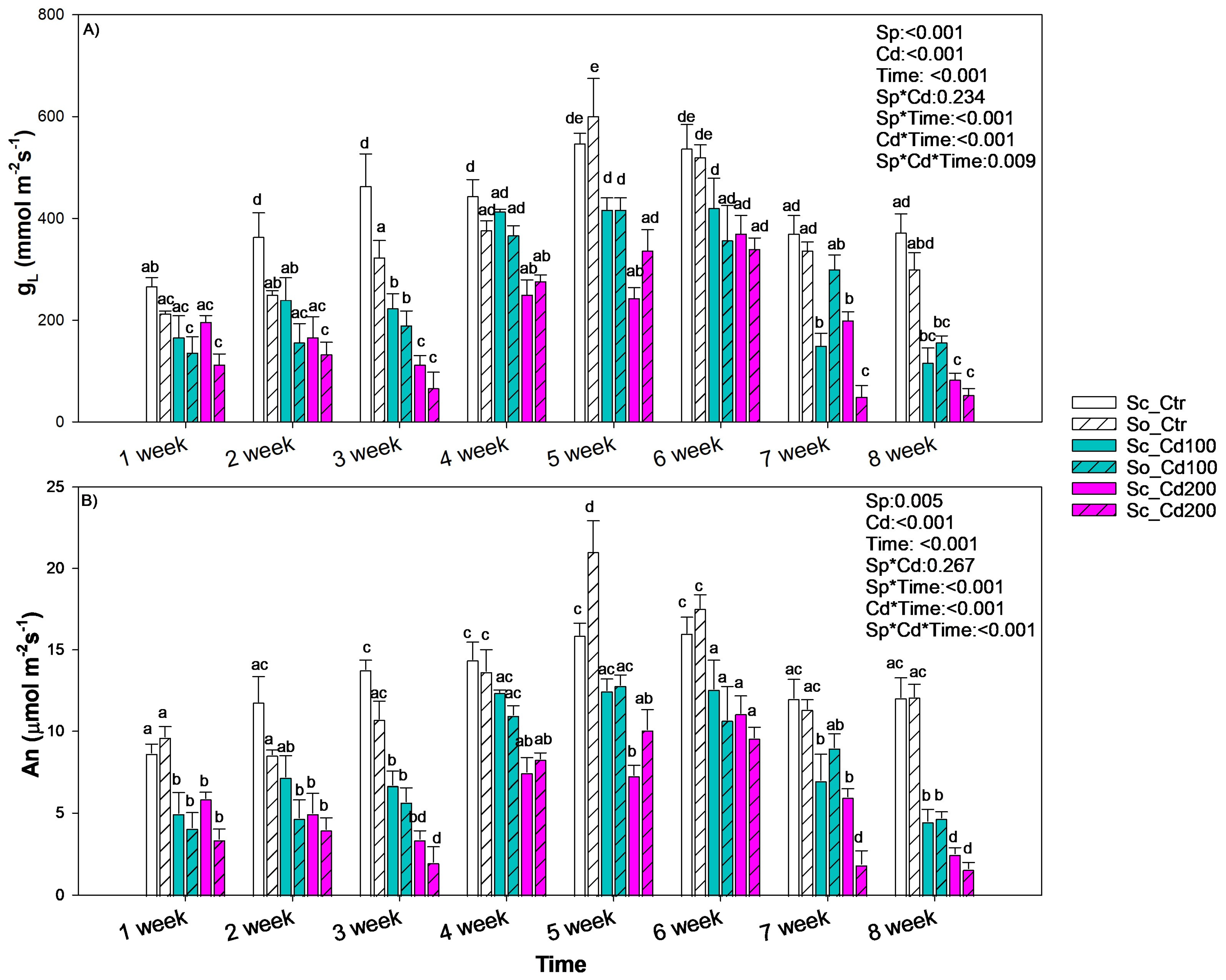

2.3. Gas Exchange, Chlorophyll a Fluorescence and Water Relations Measurements

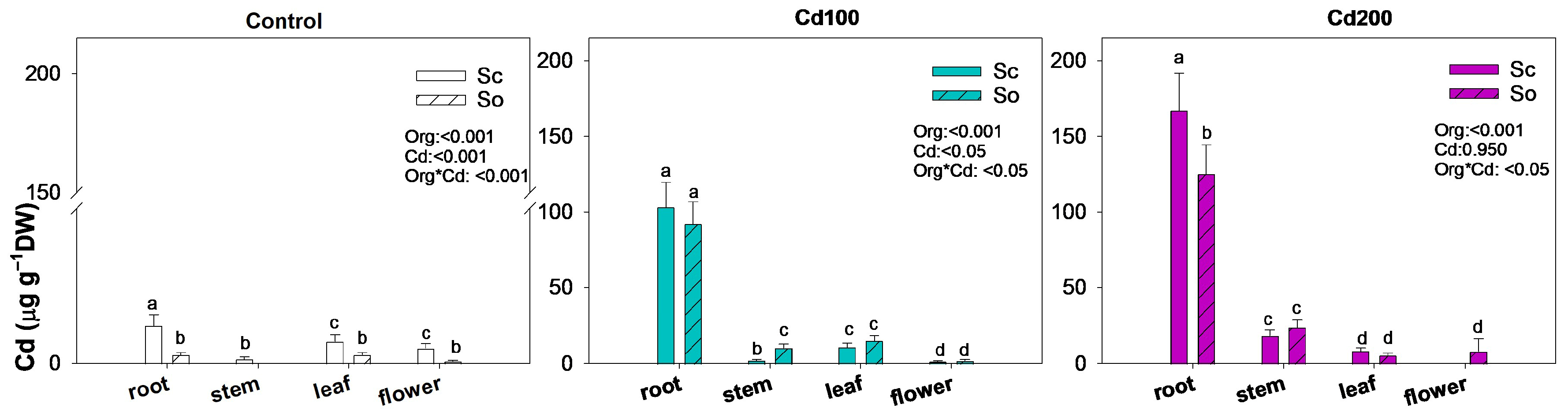

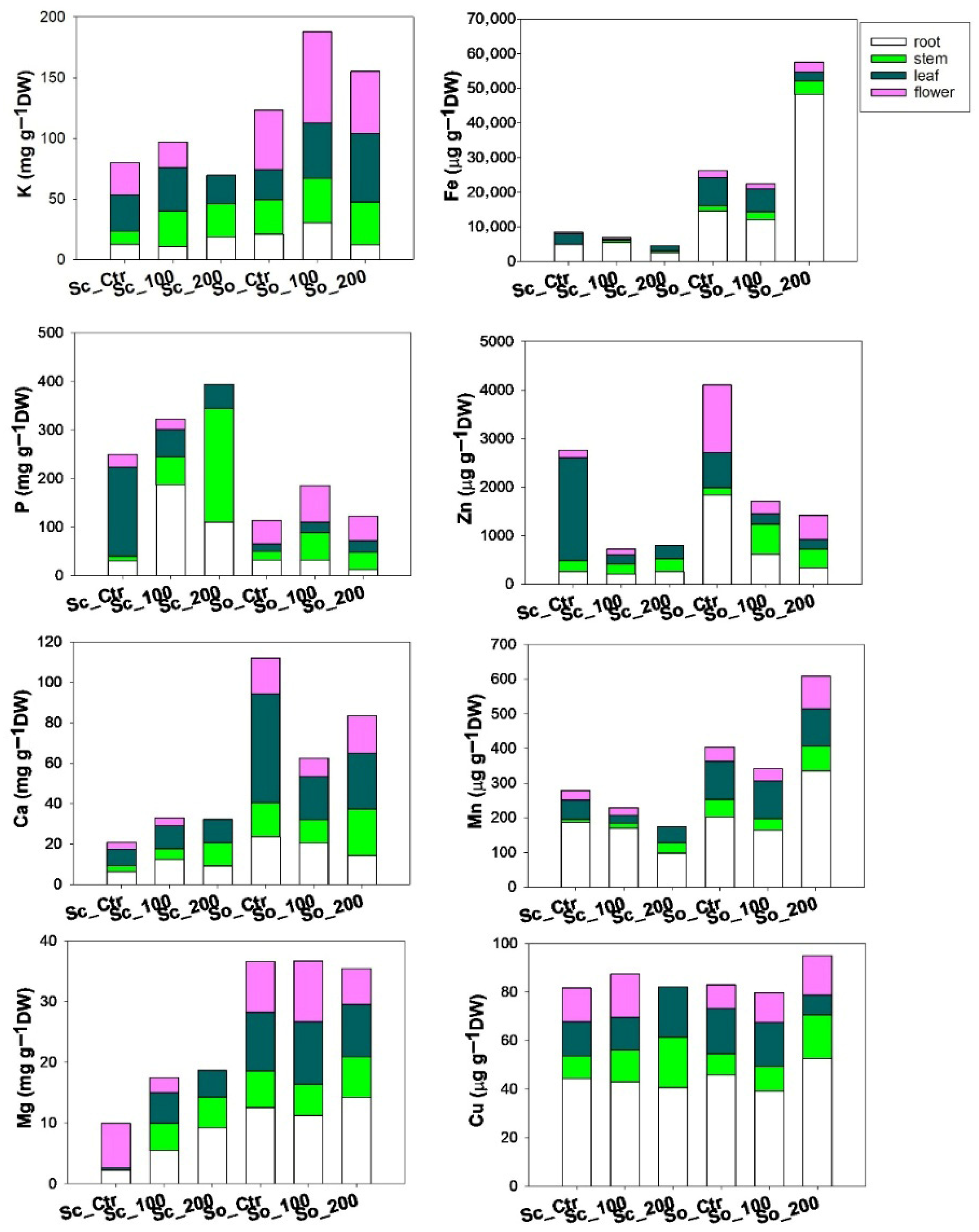

2.4. ICP-OES Mineral Element Analysis

2.5. Leaf Extraction Procedure

2.6. Determination of Polyphenolic Compounds by HPLC-PDA/ESI-MS

2.7. In Vitro Antioxidant Assays

2.8. Artemia Salina Lethality Bioassay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Morpho-Physiological Traits

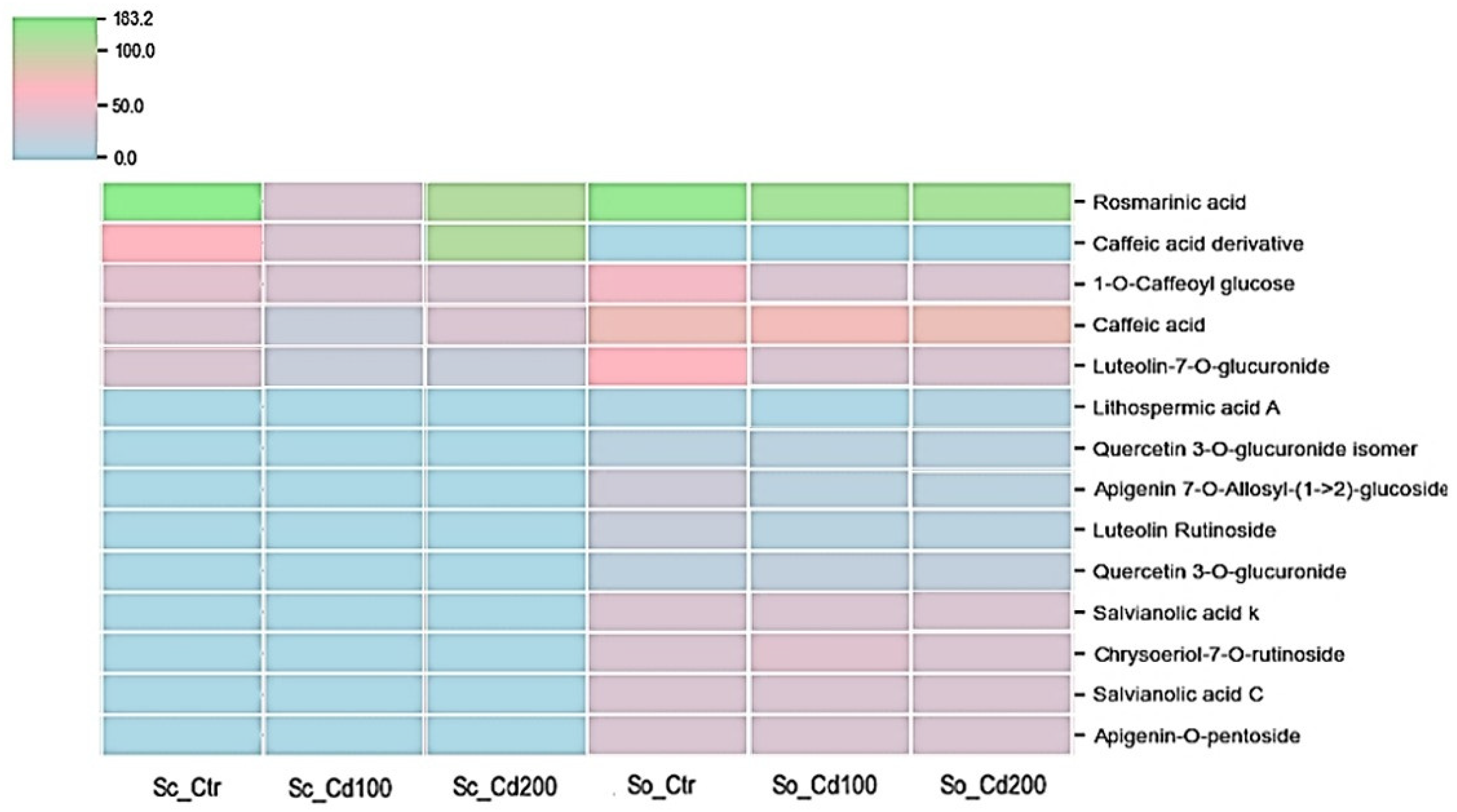

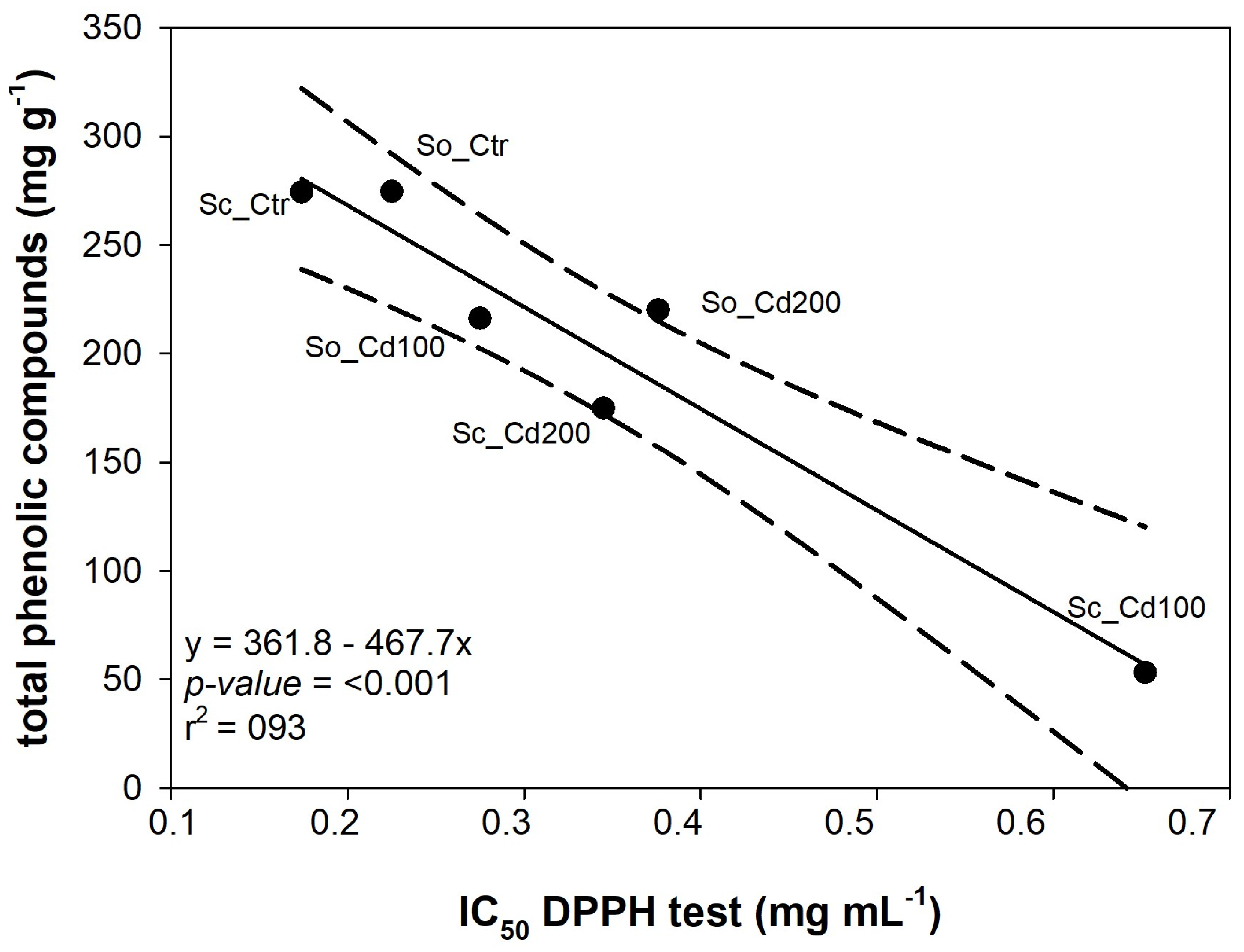

4.2. Phenolic Metabolism and Antioxidant Responses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goyal, D.; Yadav, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Singh, S. Effect of heavy metals on plant growth: An overview. In Contaminants in Agriculture; Naeem, M., Ansari, A.A., Gill, S.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugaraj, B.M.; Malla, A.; Ramalingam, S. Cadmium stress and toxicity in plants: An overview. In Cadmium Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants; Hasanuzzaman, M., Prasad, M.N.V., Fujita, M., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.U.; Cai, L.; Coulter, J.A.; Cheema, S.A.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Wenjun, M.; Farooq, M. Cadmium toxicity in plants: Impacts and remediation strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 211, 111887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, R.; Mu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Xing, W.; Liu, D. Cadmium toxicity in plants: From transport to tolerance mechanisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2544316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterckeman, T.; Thomine, S. Mechanisms of cadmium accumulation in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2020, 39, 322–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Kariman, K. Physiological and antioxidative responses of medicinal plants exposed to heavy metals stress. Plant Gene 2017, 11, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Vasudev, P.G. MYB transcription factors and their role in medicinal plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 10995–11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, G.; Pande, C.; Tewari, G.; Singh, C.; Kharkwal, G.C. Effect of heavy metals on terpenoid composition of Ocimum basilicum L. and Mentha spicata L. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2015, 18, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, R.A.; Alberton, O.; Gazim, Z.C.; Laverde, A., Jr.; Caetano, J.; Amorin, A.C.; Dragunski, D.C. Phytoaccumulation and effect of lead on yield and chemical composition of Mentha crispa essential oil. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 3007–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magray, J.A.; Sharma, D.P.; Deva, M.A.; Thoker, S.A. Phenolics: Accumulation and role in plants grown under heavy metal stress. In Plant Phenolics in Abiotic Stress Management; Lone, R., Khan, S., Al-Sadi, A.M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Farhat, M.; Landoulsi, A.; Chaouch-Hamada, R.; Sotomayor, J.A.; Jordán, M.J. Characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of Salvia species growing in different habitats. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeshvaghani, Z.A.; Rahimmalek, M.; Talebi, M.; Goli, S.A.H. Comparison of total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in different Salvia species using three model systems. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, E.; Nardini, A.; Trifilò, P. Too dry to survive: Leaf hydraulic failure in two Salvia species can be predicted on the basis of water content. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, E.; Azzarà, M.; Trifilò, P. When water availability is low, two mediterranean Salvia species rely on root hydraulics. Plants 2021, 10, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescio, R.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Araniti, F.; Musarella, C.M.; Sofo, A.; Laface, V.L.A.; Spampinato, G.; Sorgonà, A. The assessment and the within-plant variation of the morpho-physiological traits and VOCs profile in endemic and rare Salvia ceratophylloides Ard. (Lamiaceae). Plants 2021, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkai, D.; Miceli, N.; Taviano, M.F.; Coppolino, C.; Cacciola, F.; Mondello, L.; Trifilò, P. Phenolic Profile and Biological Evaluation of Salvia ceratophylloides Ard.: A Novel Source of Rosmarinic Acid. Chem. Biodivers. 2026, Accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileto, S.; Spagnuolo, D.; Lupini, A.; Battipaglia, G.; Bressi, V.; Espro, C.; Genovese, G.; Crisafulli, A.; Vigilanti, D.; Zaccariello, L.; et al. Hydrochar from garden waste enhances drought tolerance via soil-plant-gene interaction. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2026, 241, 106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiofalo, M.T.; Bekkai, D.; Mileto, S.; Furnari, P.; Genovese, G.; Trifilò, P. Early water-status indicators under combined metal toxicity and drought in tomato leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzellis, F.; Nardini, A.; Savi, T.; Tonet, V.; Castello, M.; Bacaro, G. Less safety for more efficiency: Water relations and hydraulics of the invasive tree Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle compared with native Fraxinus ornus L. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, M.; Morishita, H.; Iwahashi, H.; Toda, S.; Shirataki, Y.; Kimura, M.; Kido, R. Inhibitory effects of chlorogenic acids on linoleic acid peroxidation and haemolysis. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyaizu, M. Studies on products of browning reaction. Antioxidative activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn. J. Nutr. Diet. 1986, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Dispenzieri, A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Hayman, S.R.; Buadi, F.K.; Zeldenrust, S.R.; Dingli, D.; Russell, S.J.; Lust, J.A.; et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood 2008, 111, 2516–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Ferrigni, N.; Putnam, J.; Jacobsen, L.; Nichols, D.; McLaughlin, J. Brine shrimp: A convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Med. 1982, 45, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, R.M.; Jovanova, B.; Kadifkova Panovska, T. Toxicological evaluation of plant products using brine shrimp (Artemia salina L.) model. Maced. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 60, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, V.; Bayon, R.C.L.; Feller, U. Partitioning of zinc, cadmium, manganese and cobalt in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and lupin (Lupinus albus) and further release into the soil. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006, 58, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascio, N.; Navari-Izzo, F. Heavy metal hyperaccumulating plants: How and why do they do it? And what makes them so interesting? Plant Sci. 2011, 180, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.; Khan, M.S. Heavy metal induced oxidative damage and root morphology alterations of maize (Zea mays L.) plants and stress mitigation by metal tolerant nitrogen fixing Azotobacter chroococcum. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 157, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkai, D.; Chiofalo, M.T.; Torre, D.; Mileto, S.; Genovese, G.; Cimino, F.; Toscano, G.; Iannazzo, D.; Trifilò, P. Chronic mild cadmium exposure increases the vulnerability of tomato plants to dehydration. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 217, 109200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucińska-Sobkowiak, R. Water relations in plants subjected to heavy metal stresses. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alia, P.; Saradhi, P. Proline accumulation under heavy metal stress. J. Plant Physiol. 1991, 138, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.S.; Dietz, K.-J. The significance of amino acids and amino acid-derived molecules in plant responses and adaptation to heavy metal stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, D.-S.; Qiu, C.-P.; Han, D.-G.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Wu, T.; Han, Z.-H. Comparison of cadmium-induced iron-deficiency responses and genuine iron-deficiency responses in Malus xiaojinensis. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wen, Q.; Ma, T.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, D.; Zhu, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, H. Cadmium-induced iron deficiency is a compromise strategy to reduce Cd uptake in rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 206, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, F.; Gáspár, L.; Morales, F.; Gogorcena, Y.; Lucena, J.J.; Cseh, E.; Kröpfl, K.; Abadía, J.; Sárvári, E. Effects of two iron sources on iron and cadmium allocation in poplar (Populus alba) plants exposed to cadmium. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocito, F.F.; Lancilli, C.; Dendena, B.; Lucchini, G.; Sacchi, G.A. Cadmium retention in rice roots is influenced by cadmium availability, chelation and translocation. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 994–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Cózatl, D.G.; Jobe, T.O.; Hauser, F.; Schroeder, J.I. Long-distance transport, vacuolar sequestration, tolerance, and transcriptional responses induced by cadmium and arsenic. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, A.R.; Scheuermann, E.B.; Prechsl, U.E.; Erenoglu, B.; Schaaf, G.; Hayen, H.; Weber, G.; von Wirén, N. Iron acquisition by phytosiderophores contributes to cadmium tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Cózatl, D.G.; Butko, E.; Springer, F.; Torpey, J.W.; Komives, E.A.; Kehr, J.; Schroeder, J.I. Identification of high levels of phytochelatins, glutathione and cadmium in the phloem sap of Brassica napus. A role for thiol-peptides in the long-distance transport of cadmium and the effect of cadmium on iron translocation. Plant J. 2008, 54, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagajyoti, P.C.; Lee, K.D.; Sreekanth, T.V.M. Heavy metals, occurrence and toxicity for plants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2010, 8, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.; Singh, M.P.; Kaur, S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Zheng, B.; Sharma, A. Modulation of the functional components of growth, photosynthesis, and anti-oxidant stress markers in cadmium exposed Brassica juncea L. Plants 2019, 8, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoufan, P.; Azad, Z.; Rahnama Ghahfarokhie, A.; Kolahi, M. Modification of oxidative stress through changes in some indicators related to phenolic metabolism in Malva parviflora exposed to cadmium. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 187, 109811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Yan, C. Phenolic metabolism and related heavy metal tolerance mechanism in Kandelia obovata under Cd and Zn stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 169, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrikova, A.G.; Apostolova, E.L.; Hanć, A.; Yotsova, E.; Borisova, P.; Sperdouli, I.; Adamakis, I.D.S.; Moustakas, M. Cadmium toxicity in Salvia sclarea L.: An integrative response of element uptake, oxidative stress markers, leaf structure and photosynthesis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Rehman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Landi, M.; Zheng, B. Response of phenylpropanoid pathway and the role of polyphenols in plants under abiotic stress. Molecules 2019, 24, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sytar, O.; Cai, Z.; Brestic, M.; Kumar, A.; Prasad, M.N.V.; Taran, N.; Smetanska, I. Foliar applied nickel on buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) induced phenolic compounds as potential antioxidants. Clean Soil Air Water 2013, 41, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C.; Ruiz, A.; Ortiz, J.; Larama, G.; Perez, R.; Santander, C.; Ferreira, P.A.A.; Cornejo, P. Antioxidant responses of phenolic compounds and immobilization of copper in Imperata cylindrica, a plant with potential use for bioremediation of Cu contaminated environments. Plants 2020, 9, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sc_Ctr | Sc_Cd100 | Sc_Cd200 | So_Ctr | So_Cd100 | So_Cd200 | Sp | Cd | Sp*Cd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hplant (cm) | 66.2 ± 2.8 a | 63.0 ±14.8 a | 33.3 ± 4.8 b | 43.0 ±4.2 c | 36.7 ± 0.5 bc | 47.0 ± 2.2 c | 0.048 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| DWflower (g) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.72 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.044 | 0.554 | 0.073 |

| DWleaf (g) | 3.2 ± 0.8 a | 4.6 ± 0.1 a | 1.6 ± 0.3 b | 4.5 ± 0.8 ac | 3.8 ± 0.7 ac | 5.2 ± 1.4 c | 0.011 | 0.373 | 0.006 |

| DWstem (g) | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.009 | 0.074 | 0.222 |

| DWroot (g) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 01 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.465 | 0.683 | 0.960 |

| TL (mm) | 0.33 ± 0.01 a | 0.39 ± 0.01 a | 0.49 ±0.02 b | 0.27 ± 0.01 c | 0.42 ± 0.01 a | 0.69 ± 0.10 ac | 0.996 | <0.001 | 0.026 |

| Leaf density (g cm−3) | 0.19 ± 0.03 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.07 ± 0.01 c | 0.33 ± 0.08 d | 0.16 ± 0.03 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 c | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| LMA (g m−2) | 64.5 ± 9.6 | 39.8 ± 2.9 | 32.5 ± 3.8 | 89.4 ± 20.8 | 67.5 ± 11.5 | 41.9 ± 6.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| LDMC (mg g−1) | 0.16 ± 0.02 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 0.09 ±0.00 b | 0.23 ± 0.03 c | 0.21 ±0.03 c | 0.15 ± 0.01 a | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| SWC (g g−1) | 5.54 ± 0.84 a | 8.45 ± 0.19 b | 9.04 ± 0.27 b | 3.41 ± 0.53 c | 3.94 ± 0.83 c | 5.51 ± 0.31 a | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| πo (MPa) | −0.67 ± 0.04 | −0.82 ± 0.08 | −0.81 ± 0.03 | −0.99 ± 0.04 | −1.12± 0.03 | −1.14 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.753 |

| Ψtlp (MPa) | −0.91 ± 0.05 | −1.11 ± 0.1 | −1.08 ± 0.03 | −1.33 ± 0.06 | −1.50 ± 0.03 | −1.53 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.596 |

| IC50, DPPH (mg mL−1) | Reducing Power (ASE mL−1) | IC50, Fe2+ Chelating Activity (mg mL−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sc_Ctr | 0.174 ± 0.007 a | 10.169 ± 0.508 a | 0.471 ± 0.011 a |

| Sc_Cd100 | 0.652 ± 0.035 b | 24.785 ± 2.866 b | 0.371 ± 0.003 b |

| Sc_Cd200 | 0.345 ± 0.019 c | 4.267 ± 0.146 c | 0.205 ± 0.004 c |

| So_Ctr | 0.225 ± 0.007 d | 9.174 ± 0.186 a | >2 d |

| So_Cd100 | 0.275 ± 0.005 e | 25.146 ± 1.585 b | >2 d |

| So_Cd200 | 0.376 ± 0.024 c | 12.536 ± 0.778 a | >2 d |

| Standard | BHT 0.070 ± 0.001 | BHT 1.443 ± 0.021 | EDTA 0.0067 ± 0.0003 |

| Sp | <0.001 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| Cd | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sp*Cd | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| LC50 (µg mL−1) | |

|---|---|

| Sc_Ctr | >1000 |

| Sc_Cd100 | >1000 |

| Sc_Cd200 | >1000 |

| So_Ctr | 79.27 ± 11.61 |

| So_Cd100 | 346.5 ± 0 |

| So_Cd200 | 92.99 ± 9.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bekkai, D.; Miceli, N.; Cimino, F.; Coppolino, C.; Taviano, M.F.; Cacciola, F.; Toscano, G.; Calabrese, L.; Trifilò, P. Differential Cadmium Responses in Two Salvia Species: Implications for Tolerance and Ecotoxicity. Plants 2026, 15, 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030375

Bekkai D, Miceli N, Cimino F, Coppolino C, Taviano MF, Cacciola F, Toscano G, Calabrese L, Trifilò P. Differential Cadmium Responses in Two Salvia Species: Implications for Tolerance and Ecotoxicity. Plants. 2026; 15(3):375. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030375

Chicago/Turabian StyleBekkai, Douaa, Natalizia Miceli, Francesco Cimino, Carmelo Coppolino, Maria Fernanda Taviano, Francesco Cacciola, Giovanni Toscano, Luigi Calabrese, and Patrizia Trifilò. 2026. "Differential Cadmium Responses in Two Salvia Species: Implications for Tolerance and Ecotoxicity" Plants 15, no. 3: 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030375

APA StyleBekkai, D., Miceli, N., Cimino, F., Coppolino, C., Taviano, M. F., Cacciola, F., Toscano, G., Calabrese, L., & Trifilò, P. (2026). Differential Cadmium Responses in Two Salvia Species: Implications for Tolerance and Ecotoxicity. Plants, 15(3), 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15030375