Evolutionary Patterns Under Climatic Influences on the Distribution of the Lycoris aurea Complex in East Asia: Historical Dynamics and Future Projections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

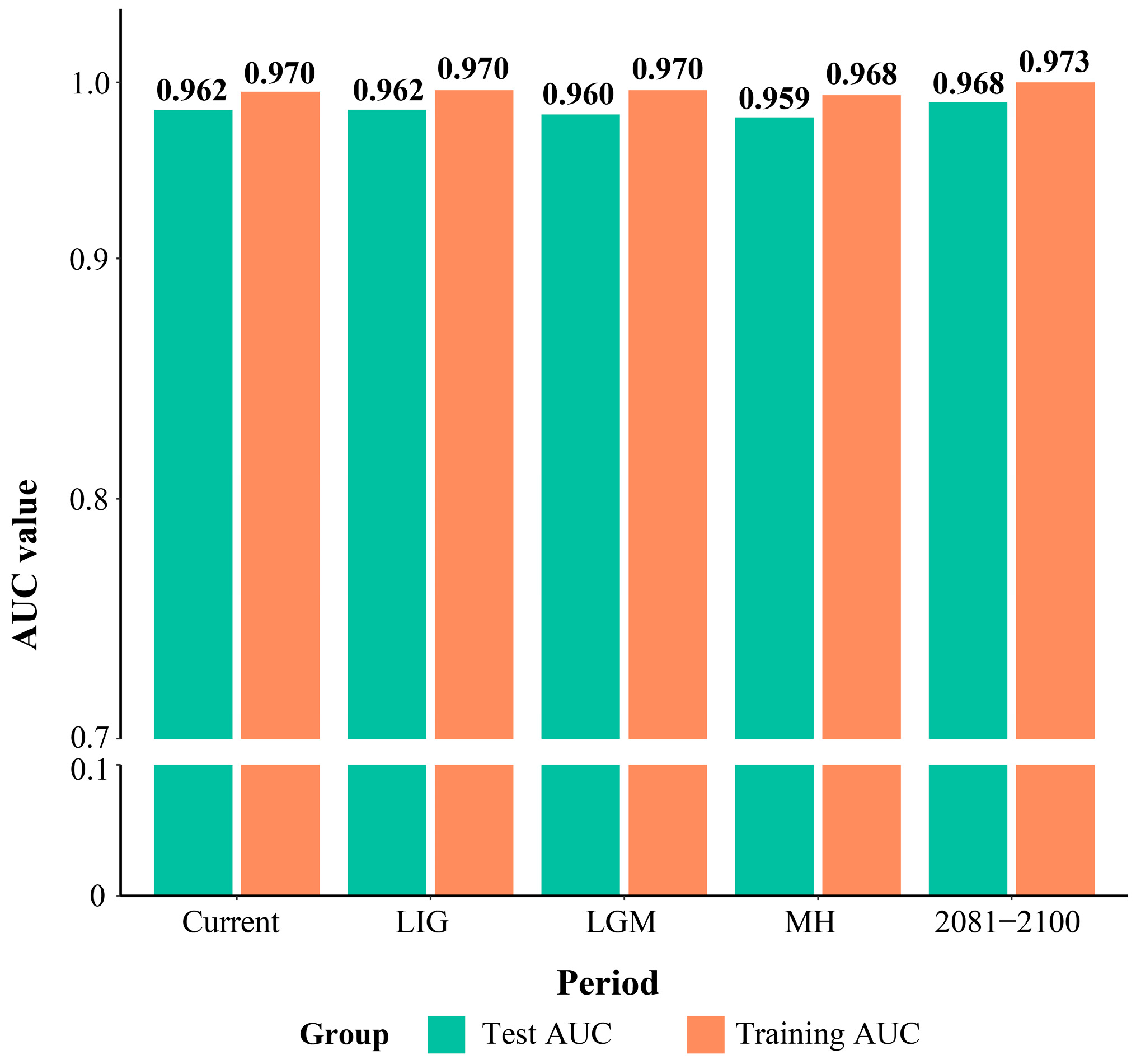

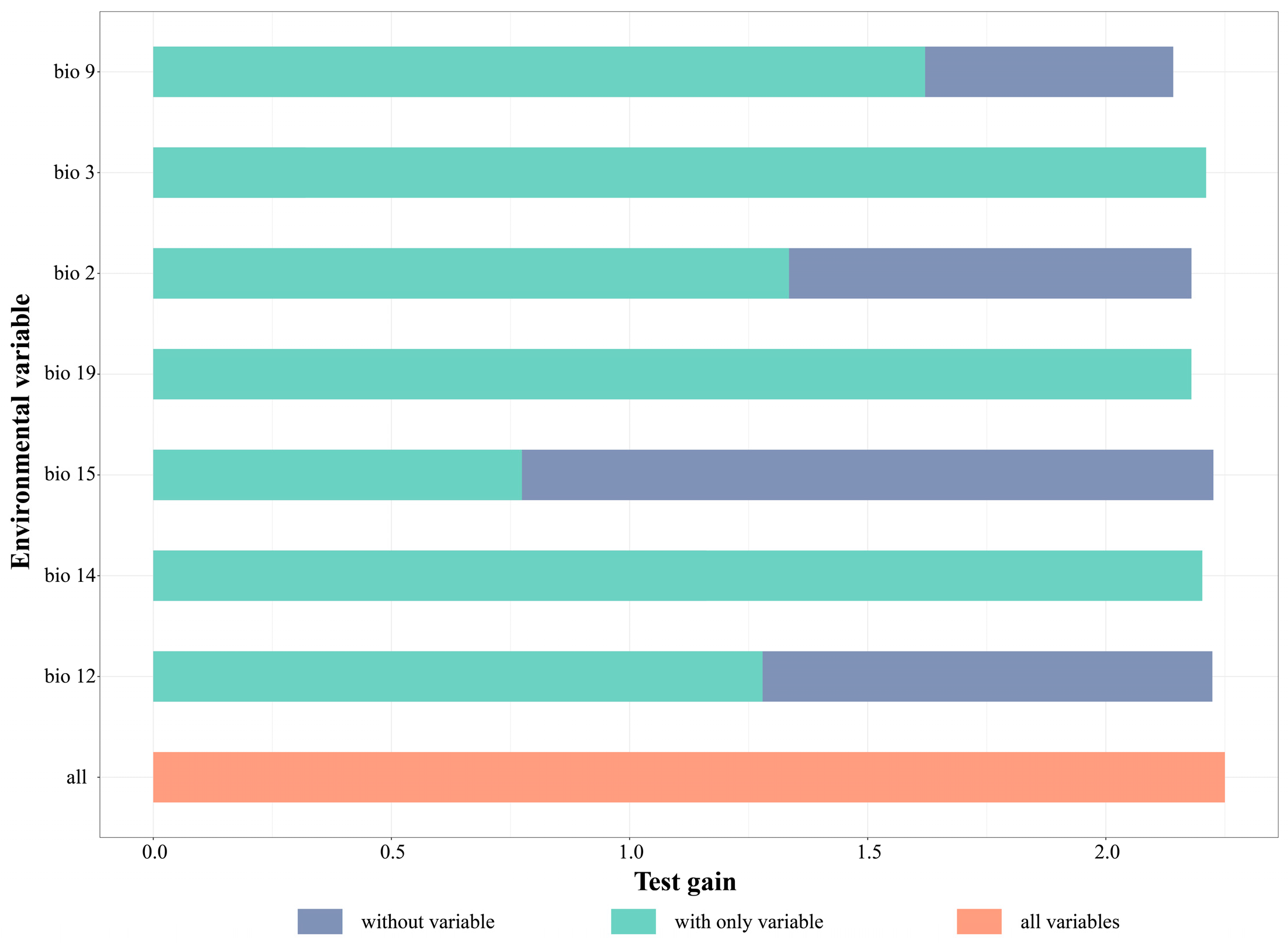

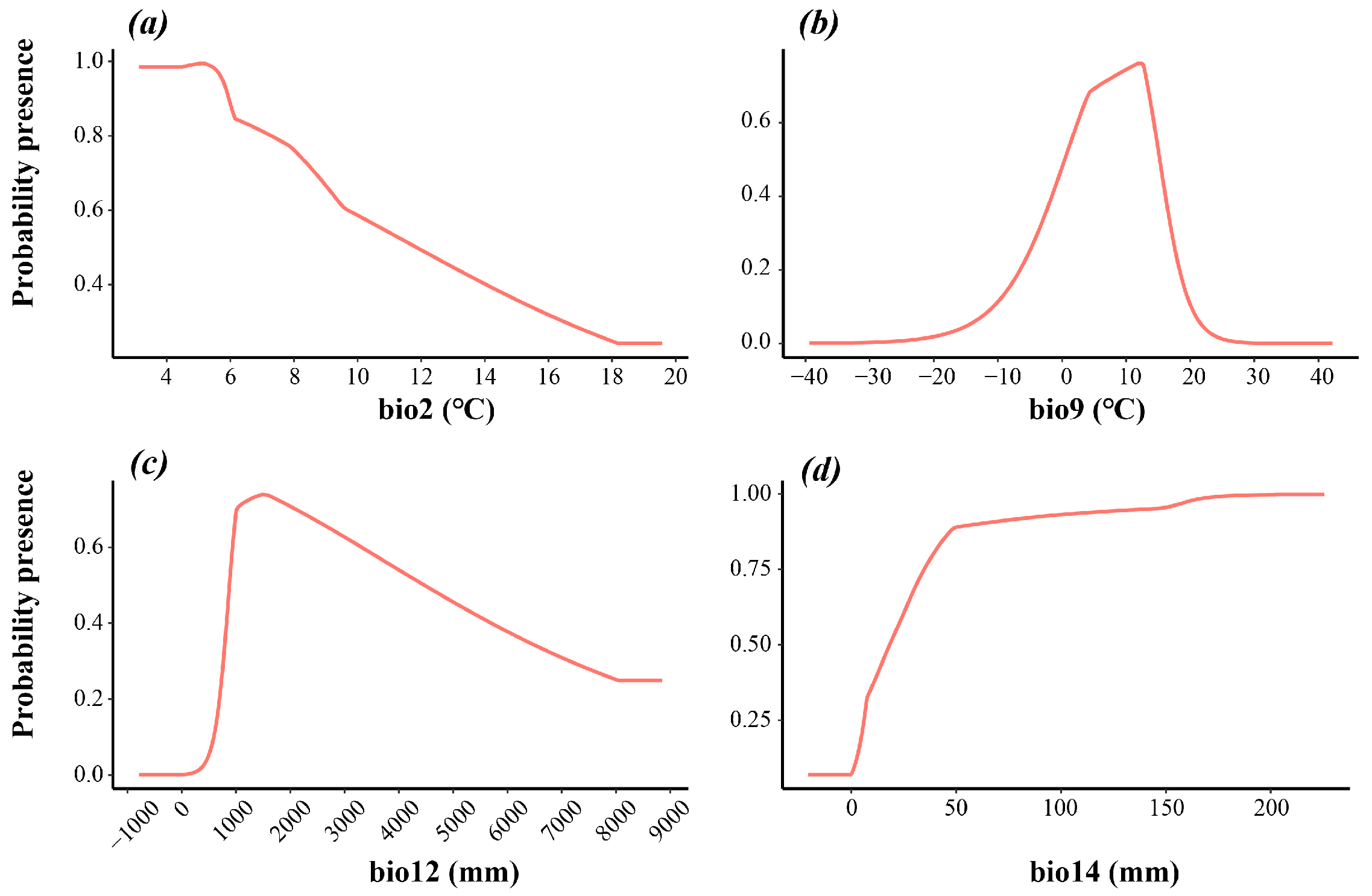

2.1. Model Parameter Optimization and Simulation

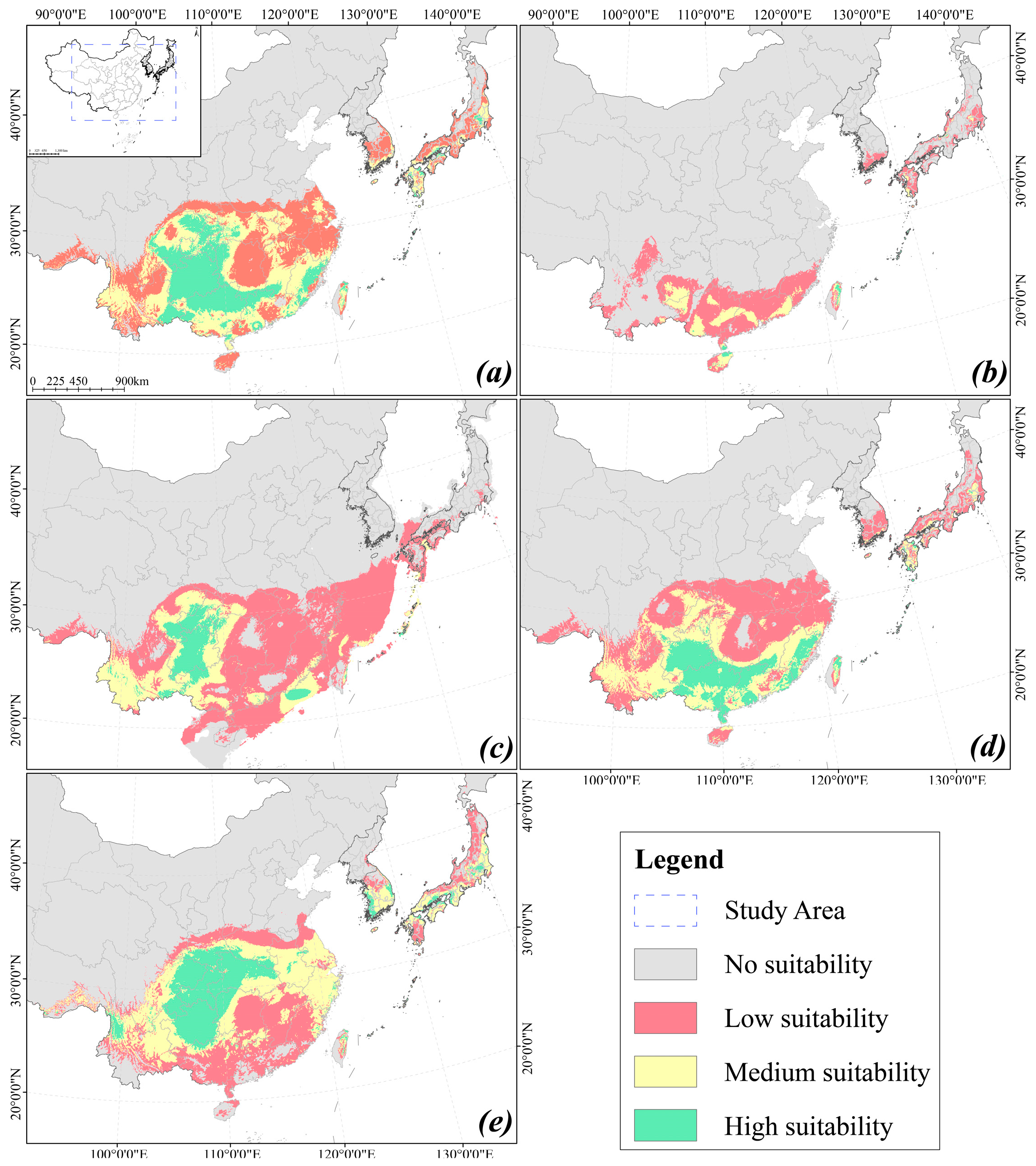

2.2. Distribution Predictions of Different Periods

2.3. Analysis of Centroid Shifts in Suitable Habitats and Migratory Paths

2.4. Potential Distribution Modeling and Divergence Analysis for the Two Major Cytotypes

3. Discussion

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics and Phylogeographic History of the Lycoris aurea Complex

3.2. Differential Impacts of Climatic Factors on Lycoris aurea Cytotypes

3.3. The “Filter Corridor” Hypothesis for the LGM East China Sea Land Bridge and Genetic Connectivity

3.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. Lycoris aurea Complex Distribution Dataset

4.1.2. Environmental Dataset

4.2. Statistical Analysis

4.2.1. MaxEnt Model Parameter Optimization

4.2.2. Model Construction and Accuracy Assessment

4.2.3. Migration and Dispersal Pathway Analysis

4.2.4. Differential Analysis of the Two Dominant Cytotype Populations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDM | Species distribution model |

| LIG | Last Interglacial (LIG, ~12–14 ka B.P.), Last Glacial Maximum |

| LGM | Three letter acronym |

| MH | Mid-Holocene |

| RM | Regularization multiplier, L (liner), Q (quadratic), H (hinge), P (product), T (threshold) |

| FC | Feature combination |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ECS | East China Sea |

References

- Siddall, M.; Rohling, E.J.; Almogi-Labin, A.; Hemleben, C.; Meischner, D.; Schmelzer, I.; Smeed, D.A. Sea-Level Fluctuations during the Last Glacial Cycle. Nature 2003, 423, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.; et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2, 2391p. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, O.; Skeels, A.; Onstein, R.E.; Jetz, W.; Pellissier, L. Earth History Events Shaped the Evolution of Uneven Biodiversity across Tropical Moist Forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2026347118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, I. Historical Biogeography: Evolution in Time and Space. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2012, 5, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Tong, X.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Z.; Miao, L.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, W.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X. Shifting Roles of the East China Sea in the Phylogeography of Red Nanmu in East Asia. J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 2486–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. Phylogeography of East Asia’s Tertiary Relict Plants: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Biodivers. Sci. 2017, 25, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbek, C.; Borregaard, M.K.; Colwell, R.K.; Dalsgaard, B.; Holt, B.G.; Morueta-Holme, N.; Nogues-Bravo, D.; Whittaker, R.J.; Fjeldså, J. Humboldt’s Enigma: What Causes Global Patterns of Mountain Biodiversity? Science 2019, 365, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.-Q.; Zhu, S.-S.; Comes, H.P.; Yang, T.; Lian, L.; Wang, W.; Qiu, Y.-X. Phylogenomics and Diversification Drivers of the Eastern Asian-Eastern North American Disjunct Podophylloideae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2022, 169, 107427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Qiao, H. Effect of the Maxent Model’s Complexity on the Prediction of Species Potential Distributions. Biodivers. Sci. 2016, 24, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, J.M.; Smith, A.B.; Warren, D.L.; Vignali, S.; Schmitt, S.; Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Arlé, E.; Márcia Barbosa, A.; Broennimann, O.; Cobos, M.E.; et al. Achieving Higher Standards in Species Distribution Modeling by Leveraging the Diversity of Available Software. Ecography 2025, 2025, e07346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.-S.; Chen, Y.; Tamaki, I.; Sakaguchi, S.; Ding, Y.-Q.; Takahashi, D.; Li, P.; Isaji, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, Y.-X. Pre-Quaternary Diversification and Glacial Demographic Expansions of Cardiocrinum (Liliaceae) in Temperate Forest Biomes of Sino-Japanese Floristic Region. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 143, 106693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Liu, G.; Bu, W.; Gao, Y. Ecological Niche Modeling and Its Applications in Biodiversity Conservation: Ecological Niche Modeling and Its Applications in Biodiversity Conservation. Biodivers. Sci. 2013, 21, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.L.; Seifert, S.N. Ecological Niche Modeling in Maxent: The Importance of Model Complexity and the Performance of Model Selection Criteria. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.-Y. Biodiversity Pursuits Need a Scientific and Operative Species Concept. Biodivers. Sci. 2016, 24, 979–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Song, M.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Hao, X.; Sun, H. A Clue to the Evolutionary History of Modern East Asian Flora: Insights from Phylogeography and Diterpenoid Alkaloid Distribution Pattern of the Spiraea japonica Complex. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2023, 184, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Wang, J.; Shrestha, N.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J. Species Identification in the Rhododendron vernicosum–R. decorum Species Complex (Ericaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 608964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ge, J.; Guo, Y.; Olmstead, R.; Sun, W. Deciphering Complex Reticulate Evolution of Asian Buddleja (Scrophulariaceae): Insights into the Taxonomy and Speciation of Polyploid Taxa in the Sino-Himalayan Region. Ann. Bot. 2023, 132, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Raven, P.H. Flora of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1999; ISBN 978-0-915279-34-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, W. Lycoris traubii, sp. nov. Plant Life 1957, 13, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kurita, S.; Hsu, P.S. Cytological Patterns in the Sino-Japanese Flora Hybrid Complexes in Lycoris, Amaryllidaceae; Bulletin No. 37; The University of Tokyo: Tokyo, Japan, 1998; Volume 37, pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.-S.; Siro, K.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Lin, J.-Z. Synopsis of the Genus Lycoris (Amaryllidaceae). SIDA Contrib. Bot. 1994, 16, 301–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kurita, S. Variation and Evolution in the Karyotype of Lycoris, Amaryllidaceae. III Intraspecific Variation in the Karyotype of L. traubii Hayward. Cytologia 1987, 52, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inariyama, S. Cytological Studies in Lycoris. Repkihara Instbiolres 1953, 6, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Zhu, H.; Lv, Y.; Meng, W.; Lv, G.; Zhang, D.; Liu, K. Aneuploidy Promotes Intraspecific Diversification of the Endemic East Asian Herb Lycoris aurea Complex. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 955724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, S. Variation and Evolution in the Karyotype of Lycoris, Amaryllidaceae. VII. Modes of Karyotype Alteration within Species and Probable Trend of Karyotype Evolution in the Genus. Cytologia 1988, 53, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, N.; Ao, M.; Zhang, P.; Yu, L. Extracts of Lycoris aurea Induce Apoptosis in Murine Sarcoma S180 Cells. Molecules 2012, 17, 3723–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, M.; Liang, J. The Influences of Four Types of Soil on the Growth, Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics of Lycoris aurea (L’ Her.) Herb. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Sun, L.; Meng, W.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Perspectives of Six Fertile Lycoris Species Endemic to East Asia Based on Plastome Characterization. Nord. J. Bot. 2022, 2022, njb.03412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Xu, C.; et al. Phylogeography and Population Demography of Parrotia subaequalis, a Hamamelidaceous Tertiary Relict ‘Living Fossil’ Tree Endemic to East Asia Refugia: Implications from Molecular Data and Ecological Niche Modeling. Plants 2025, 14, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, B.; Xu, H.; Liang, Z.; Lu, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, W. Potential Distribution of Two Economic Laver Species-Neoporphyra haitanensis and Neopyropia yezoensis under Climate Change Based on MaxEnt Prediction and Phylogeographic Profiling. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yao, S.; Sun, Y.; Degen, A.A.; Dong, L.; Luo, J.; Xie, S.; Hou, Q.; Tang, D.; et al. Distribution Range and Richness of Plant Species Are Predicted to Increase by 2100 Due to a Warmer and Wetter Climate in Northern China. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The Theory of Island Biogeography; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, R.G.; Roderick, G.K. Arthropods on Islands: Colonization, Speciation, and Conservation. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002, 47, 595–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Médail, F.; Diadema, K. Glacial Refugia Influence Plant Diversity Patterns in the Mediterranean Basin. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.-X.; Fu, C.-X.; Comes, H.P. Plant Molecular Phylogeography in China and Adjacent Regions: Tracing the Genetic Imprints of Quaternary Climate and Environmental Change in the World’s Most Diverse Temperate Flora. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2011, 59, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H. Species-level Phylogeographical History of Myricaria Plants in the Mountain Ranges of Western China and the Origin of M. laxiflora in the Three Gorges Mountain Region. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 2700–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, M.L.; Rossetto, M.; Crisp, M.D.; Weston, P.H. The Impact of Multiple Biogeographic Barriers and Hybridization on Species-level Differentiation. Am. J. Bot. 2012, 99, 2045–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Ree, R.H. Uplift-Driven Diversification in the Hengduan Mountains, a Temperate Biodiversity Hotspot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3444–E3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.J.; Reich, P.B.; Westoby, M.; Ackerly, D.D.; Baruch, Z.; Bongers, F.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Chapin, T.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Diemer, M.; et al. The Worldwide Leaf Economics Spectrum. Nature 2004, 428, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, D.L.; Wilf, P.; Janesko, D.A.; Kowalski, E.A.; Dilcher, D.L. Correlations of Climate and Plant Ecology to Leaf Size and Shape: Potential Proxies for the Fossil Record. Am. J. Bot. 2005, 92, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sack, L.; Frole, K. Leaf Structural Diversity Is Related to Hydraulic Capacity in Tropical Rain Forest Trees. Ecology 2006, 87, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.M.; Green, W.A.; Zhang, Y. Leaf Margins and Temperature in the North American Flora: Recalibrating the Paleoclimatic Thermometer. Glob. Planet. Change 2008, 60, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppe, D.J.; Royer, D.L.; Cariglino, B.; Oliver, S.Y.; Newman, S.; Leight, E.; Enikolopov, G.; Fernandez-Burgos, M.; Herrera, F.; Adams, J.M.; et al. Sensitivity of Leaf Size and Shape to Climate: Global Patterns and Paleoclimatic Applications. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirmans, P.G.; Kolář, F. Whole-Genome Duplication Leads to Significant but Inconsistent Changes in Climatic Niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2424785122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, T.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L. Estimating the Amount of the Wild Artemisia Annua in China Based on the MaxEnt Model and Spatio-Temporal Kriging Interpolation. Plants 2024, 13, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lee, J.; Fu, C.; Comes, H.P. Molecular Phylogeography of East Asian Kirengeshoma (Hydrangeaceae) in Relation to Quaternary Climate Change and Landbridge Configurations. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otofuji, Y.; Itaya, T.; Matsuda, T. Rapid Rotation of Southwest Japan-Palaeomagnetism and K-Ar Ages of Miocene Volcanic Rocks of Southwest Japan. Geophys. J. Int. 1991, 105, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Liu, A.; Yin, M.; Mu, W.; Wu, S.; Hu, H.; Chen, J.; Su, X.; Dou, Q.; Ren, G. A Genome Assembly for Orinus kokonorica Provides Insights into the Origin, Adaptive Evolution and Further Diversification of Two Closely Related Grass Genera. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, H.; Shu, L.; Huang, W.; Zhu, R. Ancient Large-scale Gene Duplications and Diversification in Bryophytes Illuminate the Plant Terrestrialization. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 2292–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Lu, R.; Heslop-Harrison, P.; Schwarzacher, T.; Wang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, F. Unraveling the Evolutionary Complexity of Lycoris: Insights into Chromosomal Variation, Genome Size, and Phylogenetic Relationships. Plant Divers. 2025, 47, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.L.; Matzke, N.J.; Cardillo, M.; Baumgartner, J.B.; Beaumont, L.J.; Turelli, M.; Glor, R.E.; Huron, N.A.; Simões, M.; Iglesias, T.L.; et al. ENMTools 1.0: An R Package for Comparative Ecological Biogeography. Ecography 2021, 44, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Boria, R.A.; Kass, J.M.; Uriarte, M.; Anderson, R.P. ENMeval: An R Package for Conducting Spatially Independent Evaluations and Estimating Optimal Model Complexity for maxent Ecological Niche Models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of Species Distributions with Maxent: New Extensions and a Comprehensive Evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Bennett, J.R.; French, C.M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: The next Generation Python-Based GIS Toolkit for Landscape Genetic, Biogeographic and Species Distribution Model Analyses. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Environment Variables | Percent Contribution | Permutation Importance | Suitable Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| bio2 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 31.3~118.43 °C |

| bio3 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 17.81~87.4% |

| bio9 | 20.4 | 22.6 | 5.0~152 °C |

| bio12 | 35.9 | 35.5 | 879.9~4464.1 mm |

| bio14 | 29.8 | 13.9 | 18.36~225.5 mm |

| bio15 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 0.59~21.3% |

| bio19 | 3.4 | 11.6 | −297.6~177.37 mm |

| Period | Suitable Distribution Area (×104 km2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Suitable | Medium Suitable | High Suitable | Total | |

| Current period | 103.60 | 86.30 | 58.71 | 248.61 |

| LIG | 62.46 | 15.65 | 1.28 | 79.39 |

| LGM | 175.23 | 62.42 | 24.97 | 262.62 |

| MH | 119.89 | 72.18 | 40.87 | 232.93 |

| 2081–2100 | 101.96 | 103.13 | 62.61 | 267.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meng, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Hou, G.; Sun, L.; Han, X.; Liu, K. Evolutionary Patterns Under Climatic Influences on the Distribution of the Lycoris aurea Complex in East Asia: Historical Dynamics and Future Projections. Plants 2026, 15, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020272

Meng W, Zhang X, Zhang H, Hou G, Sun L, Han X, Liu K. Evolutionary Patterns Under Climatic Influences on the Distribution of the Lycoris aurea Complex in East Asia: Historical Dynamics and Future Projections. Plants. 2026; 15(2):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020272

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Weiqi, Xingshuo Zhang, Haonan Zhang, Guoshuai Hou, Lianhao Sun, Xiangnan Han, and Kun Liu. 2026. "Evolutionary Patterns Under Climatic Influences on the Distribution of the Lycoris aurea Complex in East Asia: Historical Dynamics and Future Projections" Plants 15, no. 2: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020272

APA StyleMeng, W., Zhang, X., Zhang, H., Hou, G., Sun, L., Han, X., & Liu, K. (2026). Evolutionary Patterns Under Climatic Influences on the Distribution of the Lycoris aurea Complex in East Asia: Historical Dynamics and Future Projections. Plants, 15(2), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020272