1. Introduction

High Nature Value (HNV) grasslands are key components of the European rural landscape, recognized for their high biodiversity, ecological functions, and cultural and economic importance [

1,

2,

3]. These semi-natural grassland systems support a wide range of ecosystem services, including soil conservation, carbon sequestration, hydrological regulation, and the preservation of traditional cultural landscapes [

4,

5,

6]. At the same time, the European Union supports High Nature Value (HNV) grasslands, which occupy significant areas, particularly in mountainous and hilly regions, where extensive farming practices and low-input fertilization—typically involving nutrient additions below 50 kg N ha

−1 year

−1—have enabled the long-term (decadal-scale) conservation of floristic diversity [

7,

8,

9]. This conservation effect is primarily linked to reduced nutrient availability, which limits competitive exclusion by fast-growing grasses and allows the persistence of stress-tolerant and oligotrophic species characteristic of semi-natural mountain grasslands. In Romania, grassland ecosystems are particularly widespread in the Carpathian Mountains, where they constitute nuclei of high natural value agriculture and are part of Natura 2000, playing an important role in biodiversity conservation and in maintaining mountain agro-cultural identity [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In the Apuseni Mountains, previous research has shown that maintaining the biodiversity of oligotrophic grasslands depends on traditional agricultural practices and the use of reduced organic inputs [

14,

15,

16]. In parallel, the continuation of traditional management practices on the grasslands of the Apuseni Mountains has shaped distinctive landscape elements that define the identity of the cultural landscape [

17,

18,

19]. Grassland ecosystems provide multiple ecosystem services that support both ecological functioning and the rural mountain economy. As provisioning ecosystem services, these grasslands supply high-quality cattle fodder with high protein and mineral content [

20,

21,

22], but also valuable medicinal plants, such as

Arnica montana, an emblematic species of the Apuseni Mountains [

23,

24,

25,

26] along with other plant resources of local interest, traditionally used in mountain households [

27,

28,

29].

Through carbon sequestration and water regime regulation, these grassland ecosystems deliver ecosystem services that contribute to climate change mitigation [

30,

31,

32,

33]. At the same time, traditionally managed mountain grasslands are important for preventing soil erosion and stabilizing slopes, contributing to the adaptation of mountain ecosystems to climate change [

34,

35,

36]. At the same time, these grassland ecosystems ensure the maintenance of soil fertility and nutrient cycling, promoting the resilience of agroecosystems through a balance between production and conservation [

37,

38]. HNV grasslands have distinct cultural and social value, being appreciated for their characteristic landscapes, for the conservation of agro-pastoral traditions, and for the high tourism potential of mountain areas [

39,

40,

41]. In this context, these grassland ecosystems face a range of anthropogenic and environmental pressures that may compromise ecological stability and ecosystem functions. Agricultural intensification, through the excessive use of mineral fertilizers and mechanization, leads to the simplification of the vegetation cover, increased dominance of competitive grasses, and reduced biodiversity [

42,

43,

44,

45].

Conversely, agricultural abandonment triggers secondary successional processes, leading to woody species establishment and reduced forage quality [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. This transition leads to a decrease in species richness and profound changes in the structure of plant communities, with the loss of economically valuable herbaceous plant species in favor of plants with high ecological plasticity, particularly fast-growing mesophilic and nitrophilous species (e.g.,

Agrostis capillaris,

Trisetum flavescens,

Taraxacum officinale), characterized by high nutrient uptake capacity, rapid biomass accumulation, and broad tolerance to increased soil fertility [

51,

52,

53,

54]. On a continental scale, the abandonment of grasslands without management interventions favors the invasion of woody species and the closure of landscapes [

55,

56], leading to significant habitat loss and associated biodiversity degradation [

57,

58]. At the same time, climate change acts as a multiplier, altering water and temperature regimes and accelerating ecological transition processes [

59,

60]. In addition, socio-economic transformations and land use changes profoundly influence the adaptive capacity of cultural landscapes in the Carpathian Mountains [

60,

61] and other European mountain regions, reducing the connectivity of traditional agro-pastoral systems [

62,

63,

64]. Organo-mineral fertilization offers a sustainable alternative to exclusively mineral fertilization [

38], allowing a balance to be maintained between productivity and the conservation of grassland ecosystem biodiversity [

65,

66], reducing greenhouse gas emissions, stabilizing the soil, without compromising the forage harvest [

67,

68]. A comparison of research focusing on fertilization systems in Romanian grasslands recommends mixed models for better sustainability of grassland ecosystems [

69,

70]. A global analysis shows the increased adoption of organo-mineral fertilizers in response to the pressure to combine agricultural efficiency with environmental protection [

71,

72]. Recent studies have shown that the combined application of organic and mineral fertilizers leads to significant increases in production and improved feed quality, even in mountain grasslands dominated by

Nardus stricta [

44,

73,

74]. Overall, organo-mineral fertilization allows for the conservation of biodiversity and the optimization of grassland ecosystem services [

75], providing a balance between forage production needs and environmental requirements [

76,

77]. Although mineral fertilizers contribute to increased productivity and improved nutritional value of fodder [

78,

79], their application in high or repeated doses leads to a decrease in floristic diversity [

37], favoring nitrophilic species and reducing the long-term stability of grassland ecosystems [

80,

81]. In contrast, the application of organo-mineral inputs supports biological processes in the soil, favoring balanced biomass growth and maintaining species characteristic of HNV grasslands [

82,

83]. The effects of organo-mineral fertilization are not limited to biomass production but also involve changes in soil chemical properties, nutrient availability, and microbial-mediated processes. Such effects can influence functional processes such as nutrient cycling, soil organic matter stabilization, and plant–soil interactions [

84,

85].

Long-term experiments are essential tools for identifying the critical ecological thresholds at which grassland ecosystems change their structure and functionality [

86,

87,

88]. In the case of HNV grasslands in mountain areas, these studies are indispensable for assessing the impact of fertilization practices—especially organo-mineral inputs—on biodiversity, productivity, and ecosystem stability. The results obtained in such long-term experiments provide valuable and reliable scientific benchmarks for defining optimal fertilization levels that are compatible with the principles of sustainable agriculture [

89,

90,

91]. At the same time, the integration of quantitative vegetation analysis methods, together with management approaches directly related to this study [

92,

93,

94] such as organo-mineral fertilization strategies, mulching, and fractional application of inputs [

95,

96], contributes to a more robust assessment of grassland ecosystem functioning in mountain environments. These approaches allow the correlation of floristic and edaphic processes with the dynamics of climatic factors, providing an integrated view of the resilience of organo-mineral fertilized grasslands. Within the European policy framework, the management of HNV grasslands is strongly guided by environmental regulations aimed at limiting nutrient inputs and conserving biodiversity. In particular, the Nitrates Directive sets upper thresholds for nitrogen application and promotes practices that reduce nutrient leaching, while the Natura 2000 Habitats framework requires the maintenance of favorable conservation status for semi-natural grassland habitats. Consequently, fertilization in mountain HNV grasslands is restricted to low-intensity inputs and carefully controlled application regimes, which directly frame the type and intensity of organo-mineral fertilization treatments assessed in the present study.

The objective of this study is to assess the long-term effects of organo-mineral fertilization on the structure, diversity, and functioning of High Nature Value grasslands in the Apuseni Mountains, based on vegetation data collected after 15 years of continuous treatment application at the plot scale (20 m2). Specifically, the study aims: (i) to quantify changes in floristic composition and plant diversity along a gradient of fertilization intensity, using species richness and standard α-diversity indices (Shannon, Simpson, and Evenness); (ii) to compare vegetation structural responses under organic, mineral, and organo-mineral fertilization regimes, with vegetation structure defined in terms of species dominance patterns, relative cover, and community composition derived from floristic surveys and multivariate analyses; and (iii) to identify fertilization thresholds that balance forage productivity and biodiversity conservation, where thresholds are interpreted as ecological limits beyond which marked shifts in plant community composition and diversity occur. In this context, the balance between productivity and conservation is defined by the maintenance of species-rich grassland communities characteristic of HNV systems while avoiding floristic simplification associated with eutrophication. The results obtained can serve as scientific support for optimizing agro-ecological practices in sensitive areas of the Apuseni Mountains and for adopting them in line with the requirements of the Nitrates Directive and Natura 2000 framework. Despite extensive research on fertilization effects in grassland ecosystems, the long-term ecological responses of HNV grasslands to organo-mineral fertilization remain insufficiently documented, particularly with respect to thresholds that balance productivity and biodiversity conservation. In this study, we address this gap by testing whether moderate organo-mineral inputs can maintain floristic diversity and community stability while avoiding the trophic shifts associated with intensive fertilization. We hypothesize that fertilization intensity generates distinct and consistent ecological responses in HNV mountain grasslands, with identifiable ecological thresholds along the nutrient gradient. Specifically, we expect that low to moderate organo-mineral inputs (≤10 t ha−1 manure combined with up to 50 kg N ha−1 year−1) maintain species-rich grassland communities, whereas fertilization levels exceeding 100 kg N ha−1 year−1 promote marked shifts toward mesotrophic and eutrophic vegetation types characterized by reduced floristic diversity. In this context, “predictable” responses refer to consistent changes in floristic composition and diversity patterns observed across treatments, rather than to formal statistical or mechanistic modeling. The optimal management level is defined ecologically as the fertilization regime that preserves high α-diversity and community structure characteristic of High Nature Value grasslands, while avoiding floristic simplification associated with intensive nutrient inputs. In this study, fertilization thresholds are quantitatively defined by nutrient input levels of ≤50 kg N ha−1 year−1, associated with the maintenance of high species richness and diversity indices, and ≥100 kg N ha−1 year−1, beyond which pronounced shifts toward mesotrophic and eutrophic plant communities and significant reductions in α-diversity were observed. These thresholds are validated by consistent changes in species richness, Shannon and Simpson indices, as well as by clear separation of treatments in multivariate analyses (PCoA, MRPP, and Indicator Species Analysis).

2. Results

The long-term fertilization experiment was established in 2001, the vegetation data analyzed in this study were collected in 2015. These data capture the cumulative effects of 15 consecutive years of fertilization on grassland floristic composition and structure, reflecting stabilized community responses to sustained nutrient inputs under consistent management conditions.

2.1. Cluster Analysis of Vegetation Under the Influence of Organo-Mineral Fertlization

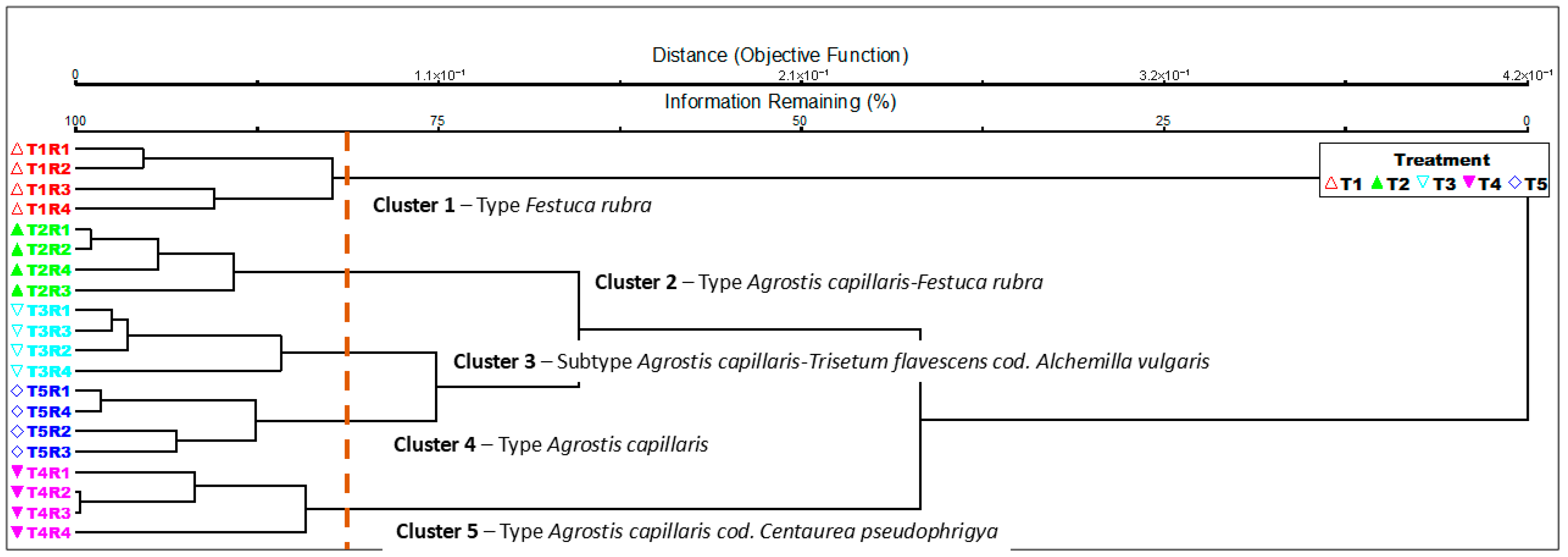

The application of organo-mineral fertilization caused major changes in the floristic composition of the grassland. Cluster analysis (Sørensen-Bray–Curtis index, UPGMA method) allowed for the clear separation of experimental areas into five distinct vegetation groups, corresponding to an ecological gradient determined by fertilization intensity (

Figure 1). Cluster 1 (

Festuca rubra grassland type) includes all control variants (T1R1–T1R4), characterized by the dominance of the

Festuca rubra species. This group represents unfertilized mountain grassland, typically oligotrophic, stable phytocenosis, with high floristic diversity and a large proportion of perennial, stress-tolerant species. Cluster 2 (

Agrostis capillaris–

Festuca rubra grassland type) represents all variants with low litter input (T2R1–T2R4). Moderate organic fertilization (10 t ha

−1) stimulated the emergence of mesotrophic species, but

Festuca rubra remained codominant. This grouping of plant communities shows a transition phase towards communities with slightly increased productivity, but still ecologically balanced. Cluster 3 (Subtype

Agrostis capillaris–

Trisetum flavescens cod.

Alchemilla vulgaris) corresponds to the variant with medium input of organic-mineral inputs (T3R1–T3R4). The presence of

Trisetum flavescens and

Alchemilla vulgaris confirms that the phytocenosis is mesotrophic, with a balanced structure between diversity and productivity. Cluster 4 (

Agrostis capillaris grassland type) includes variants fertilized only with mineral inputs (T4R1–T4R4), in which the species

Agrostis capillaris becomes dominant. This type of plant community shows a tendency toward a decrease in floristic composition and an increase in the proportion of nitrophilous plant species. Cluster 5 (

Agrostis capillaris cod.

Centaurea pseudophrygia) is represented by all variants with high fertilization inputs (T5R1–T5R4), where there are communities of plants with highly productive mesophilic species and the species

Centaurea pseudophrygia appears codominant, with a more uniform floristic composition and reduced floristic diversity [

37,

97].

The results of the cluster analysis were also confirmed by the PCoA analysis, which highlights the same floristic groupings corresponding to the trophic gradient determined by the organo-mineral fertilization inputs.

2.2. Spatial Distance in Plant Community Projection Due to Long-Term Fertilization Organo-Mineral

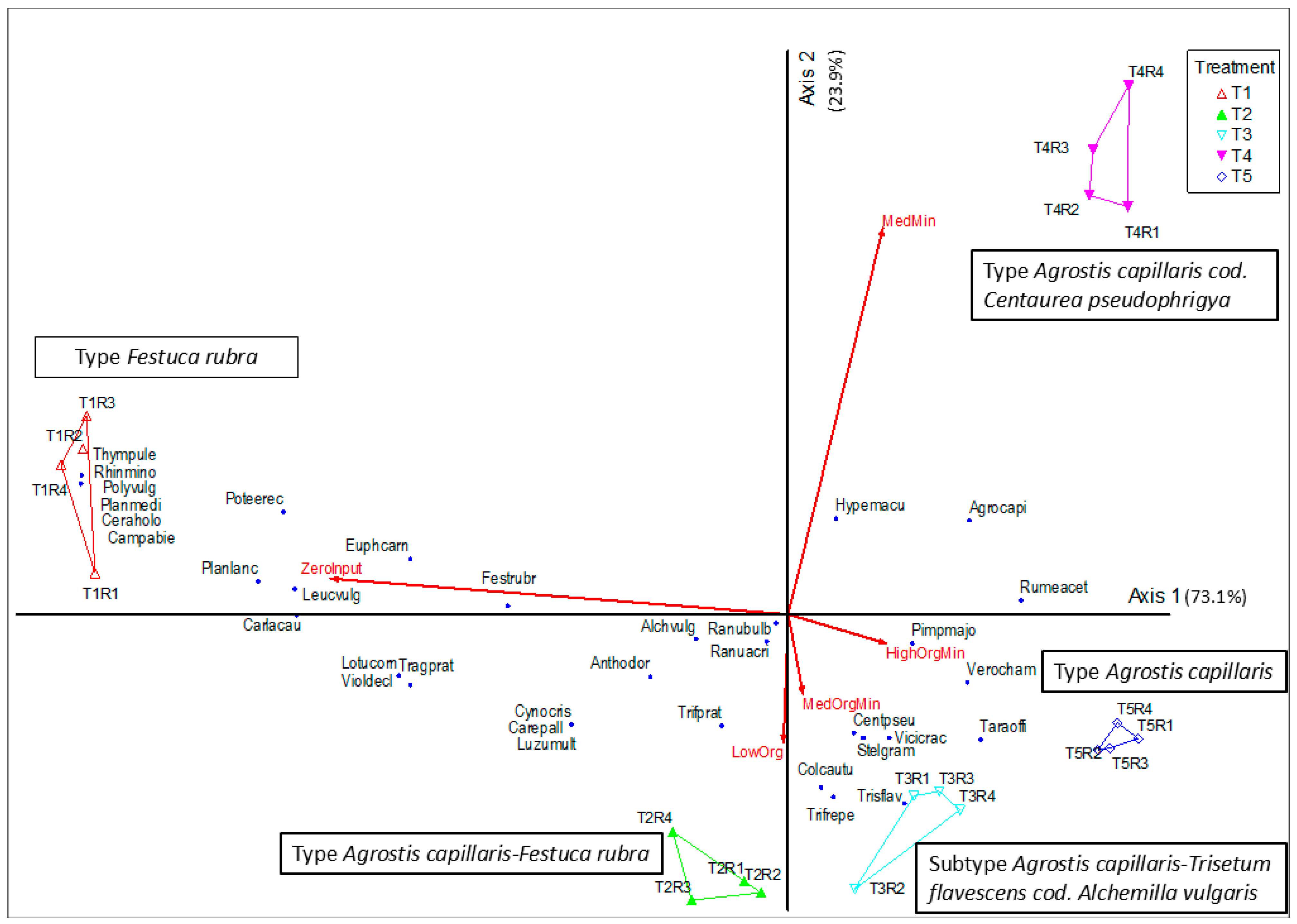

The PCoA (Principal Coordinates Analysis) analysis, performed based on the Bray–Curtis distance, showed a clear separation of the experimental variants according to the intensity of fertilization (

Figure 2). The first two ordinal axes together explain 97% of the total variation in floristic composition, confirming the relevance of the trophic gradient in structuring plant communities (

Table 1), axis 1 being the most important.

The main ecological gradient, corresponding to the level of mineral inputs, was outlined on axis 1 (73.1%). The control variants (ZeroInput) and those with reduced organic fertilization (LowOrg) are grouped on the negative side of the axis, being associated with species characteristic of oligotrophic grasslands, such as Festuca rubra, Carex pallescens, Luzula multiflora and Trifolium pratense. In contrast, the medium and high fertilization variants (MedMin and HighOrgMin) are on the positive side, correlated with the species Agrostis capillaris, Trisetum flavescens, Hypericum maculatum and Centaurea pseudophrygia, indicating a mesotrophic to eutrophic plant community.

Axis 2 (23.9%) describes secondary variations associated with differences between organic and organo-mineral fertilization types. The MedOrgMin and LowOrg variants occupy an intermediate position, confirming a transitional floral structure between preserved communities and those with predominantly mineral fertilization. Beyond the main trophic gradient expressed by Axis 1, Axis 2 reflects differences in plant community composition related to the fertilization regime. This axis distinguishes treatments managed with organic or organo-mineral inputs from those receiving exclusively mineral fertilization, indicating that vegetation responses are influenced not only by nutrient intensity but also by the form of fertilization. Consequently, Axis 2 captures a management-driven fertilization gradient that complements the primary intensity gradient.

The association of experimental vectors with ordinal axes (

Table 2) shows a significant negative correlation between axis 1 and the

ZeroInput (T1) treatment (r = −0.922,

p < 0.001), respectively, positive correlations between the same axis and

MedMin treatments (r = 0.419,

p < 0.05) and

HighOrgMin (r = 0.427,

p < 0.05). These relationships confirm that the main gradient of variation (Axis 1) reflects the intensification of fertilization and the floristic transition from oligotrophic to mesotrophic and eutrophic grasslands. The axis shows secondary variations mainly related to the type of fertilization. The association is strongly positive for the mineral treatment

MedMin/T4 (r = 0.846,

p < 0.001), while

LowOrg/T2 (r = −0.487,

p < 0.01) and

MedOrgMin/T3 (r = −0.385,

p < 0.05) show negative associations, indicating the difference between mineral and organic/organo-mineral input on this axis.

HighOrgMin/T5 has a slightly negative association (r = −0.233; insignificant), and the

ZeroInput/T1 control has a modest positive association (r = 0.258; insignificant). PCoA analysis, T4 treatments are on the positive side of Axis 2, T2–T3 on the negative side, and T1 positions close to the center. This model shows that Axis 2 separates the type of fertilization (mineral vs. organic/organo-mineral), while Axis 1 orders the intensity of the trophic gradient.

The results are consistent with the cluster analysis, both methods indicating a succession from oligotrophic Festuca rubra type of grasslands to plant communities such as mesotrophic Agrostis capillaris–Trisetum flavescens and eutrophic Agrostis capillaris–Centaurea pseudophrygia. This ranking highlights the ecological gradient from preserved grassland systems to intensified systems, generated by the increasing input of nutrients.

MRPP analysis (

Table 3) confirmed the existence of significant differences in floristic composition between all experimental treatment variants. Negative values in statistics T (between −4.35 and −4.47) indicates a clear separation between the experimental groups, and the positive values of coefficient A (0.42–0.74) reflect a high degree of homogeneity within each group of plant communities. All comparisons between treatments were statistically significant (

p < 0.01), showing that each fertilization level—organic, organo-mineral, or mineral—generated a distinct floristic composition with consistent ecological differences. The strongest separation was recorded between the control variant (T1) and the mineral-fertilized variants (T4; A = 0.741) or organo-mineral variants (T3; A = 0.703), indicating that nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization causes the greatest changes in the structure of plant communities. Also, the differences between variants T2 (reduced organic fertilization) and T3–T4 were significant, but with lower values of coefficient A, indicating a gradual transition between oligotrophic and mesotrophic phytocenoses.

The separation of the fertilized variants with high-intensity inputs (T4 and T5) had a lower A coefficient (0.593), indicating a tendency toward floristic homogenization at high input levels. The MRPP analysis validates the results obtained through cluster and PCoA, confirming that the intensification of fertilization drives an ordered ecological succession, from oligotrophic Festuca rubra grasslands toward plant communities such as the mesotrophic Agrostis capillaris–Trisetum flavescens and the eutrophic Agrostis capillaris–Centaurea pseudophrygia.

2.3. The Response of Plant Species to Organo-Mineral Inputs

The correlation analysis between the dominant plant species and the ordination axes (

Table 4) highlights a clear trophic gradient associated with Axis 1, which separates species characteristic of oligotrophic grasslands from those of mesotrophic and eutrophic conditions. On Axis 1, positive values of the r coefficient correspond to mesotrophic and nitrophilic species, characteristic of mineral and organo-mineral fertilization treatments, such as

Agrostis capillaris (r = 0.787,

p < 0.001),

Trisetum flavescens (r = 0.300,

p < 0.05),

Rumex acetosa (r = 0.653,

p < 0.01),

Taraxacum officinale (r = 0.617,

p < 0.01),

Hypericum maculatum (r = 0.291,

p < 0.05) and

Veronica chamaedrys (r = 0.728,

p < 0.01). These species define mesotrophic–eutrophic communities, developed on soils with high nitrogen and phosphorus availability, resulting mainly from combined organic-mineral fertilization. Species with strongly negative

r-values are associated with oligotrophic, unfertilized or only slightly fertilized grasslands, such as

Festuca rubra (r = −0.952,

p < 0.001),

Carex pallescens (r = −0.691,

p < 0.001),

Luzula multiflora (r = −0.691,

p < 0.001),

Lotus corniculatus (r = –0.828,

p < 0.001),

Alchemilla vulgaris (r = −0.507,

p < 0.01),

Carlina acaulis (r = −0.840,

p < 0.001) and

Thymus pulegioides (r = −0.922,

p < 0.001). These species are sensitive to increases in soil fertility, indicating the maintenance of the HNV grassland character in the control and low-input organic variants.

On Axis 2, secondary variation patterns related to the type of fertilization can be observed. Significant positive correlations were recorded for Hypericum maculatum (r = 0.826, p < 0.001) and Agrostis capillaris (r = 0.584, p < 0.01), indicating the preference of these species for mineral and organo-mineral fertilization treatments. Negative correlations characterize species associated with organic fertilization, such as Trifolium repens (r = −0.783, p < 0.001), Trifolium pratense (r = −0.503, p < 0.01), Centaurea pseudophrygia (r = −0.742, p < 0.001), Colchicum autumnale (r = −0.887, p < 0.001) and Stellaria graminea (r = −0.576, p < 0.01). This distribution confirms that Axis 1 reflects the intensity of fertilization, whereas Axis 2 differentiates the type of inputs applied (organic vs. mineral). From an ecological perspective, the results indicate a floristic transition from oligotrophic Festuca rubra-type grasslands toward mesotrophic Agrostis capillaris–Trisetum flavescens plant communities, dominated by species adapted to more fertile and productive soils.

The additional analysis of correlations among plant communities revealed patterns consistent with those obtained through ISA and PCoA, confirming the positive associations of mesotrophic species under moderate fertilization treatments and the clear separation of oligotrophic species in the control variants. This supports the ecological coherence of the identified trophic gradient.

2.4. Indicator Species Analisys to the Gradient of Applied Inputs Organo-Mineral

The ISA analysis (

Table 5) highlighted clear groups of indicator species corresponding to each fertilization level, confirming the trophic gradient previously identified through ordination and cluster analysis. For the control variant (T1—

Zero-input), the highest number of species with significant indicator values (

p < 0.01) was identified, including

Festuca rubra,

Campanula abietina,

Cerastium holosteoides,

Plantago media,

Potentilla erecta,

Thymus pulegioides and

Rhinanthus minor. These species are characteristic of oligotrophic, low-fertility mountain grasslands, preserving the traditional floristic composition and the biodiversity typical of HNV grasslands.

In the variants with low-level organic fertilization (T2—Low-input), species such as Trifolium pratense and Trifolium repens (p < 0.05) were associated, indicating a moderate increase in soil fertility and enhanced productivity without a complete loss of floristic diversity. These legume species contribute to the natural enrichment of nitrogen, supporting the ecological balance of the grassland ecosystem. For the medium organo-mineral fertilization variant (T3—MedOrgMin), species such as Trisetum flavescens and Alchemilla vulgaris (p < 0.05) were highlighted, mesotrophic species that prefer soils with moderate fertility. They define transitional plant communities, typical of productive grasslands, but still ecologically stable. In the mineral fertilization variant (T4—MedMin), indicator species such as Agrostis capillaris and Hypericum maculatum (p < 0.01) were identified, characterizing mesotrophic–eutrophic plant communities dominated by highly productive perennial grasses. For the high organo-mineral input treatment (T5—HighOrgMin), species such as Taraxacum officinale, Veronica chamaedrys, Pimpinella major and Centaurea pseudophrygia were identified, which are typical of eutrophic grasslands with reduced floristic diversity and a predominance of nitrophilous elements.

The ISA analysis confirms a directed ecological succession: from oligotrophic Festuca rubra plant communities (unfertilized) to mesotrophic Agrostis capillaris–Trisetum flavescens types and eutrophic Agrostis capillaris–Centaurea pseudophrygia communities as fertilization intensity increases. These results are in strong agreement with those obtained through PCoA and MRPP, emphasizing the coherence of the fertilization-induced trophic gradient in the structure of HNV mountain vegetation.

2.5. Effects of Organo-Mineral Fertilization on Plant Diversity

The diversity index values show a significant effect of fertilization on grassland biodiversity (

p < 0.001 for all indices). Species richness (S) decreased gradually from 31.75 species in the control variant (V1) to 17.25 species in the intensive mineral fertilization variant (V4). This reduction of more than 45% highlights the eutrophication effect of mineral fertilization on mountain plant communities, leading to the dominance of competitive grasses, particularly

Agrostis capillaris and

Trisetum flavescens, at the expense of conservative perennial species such as

Festuca rubra and

Carex pallescens. The decline in species richness is associated with the gradual replacement of oligotrophic and conservation-relevant species by mesotrophic and nitrophilous species better adapted to soils with increased nitrogen and phosphorus availability. The Shannon index (H′) followed the same trend, decreasing from 2.62 (

Table 6) in the control to 1.62 in V4, confirming the structural simplification of the plant communities as fertilization intensity increased. In contrast, reduced organic fertilization (V2—Low-input) maintained high diversity values (H′ = 2.75), even higher than the control, due to the stimulation of legume species (

Trifolium pratense,

T. repens) and mesotrophic species (

Alchemilla vulgaris), without negative effects on conservation-relevant species. The Evenness index (E) showed high values (>0.8) in the control, organic, and organo-mineral variants, indicating a balanced distribution of species abundances. In contrast, the intensive mineral fertilization variant (V4) exhibited low evenness values (E = 0.57), caused by the pronounced dominance of nitrophilous species (

Agrostis capillaris,

Trisetum flavescens). The Simpson index (D) followed the same pattern, with high values (0.89–0.91) in the reduced-input treatments and minimum values (0.63) under intensive fertilization, confirming the decline in α-diversity and the increasing dominance of competitive species. Overall, the results show that moderate organic or organo-mineral fertilization helps maintain floristic balance and preserve the biodiversity of HNV grasslands, whereas intensive mineral fertilization significantly reduces species richness and evenness, promoting structurally simplified eutrophic grassland types.

Table 6.

The influence of organo-mineral fertilizer on plant diversity.

Table 6.

The influence of organo-mineral fertilizer on plant diversity.

| Variant | Species no. (S) | Shannon (H′) | Evenness (E) | Simpson (D) |

|---|

| V1 (martor) | 31.75 ± 0.50 a | 2.62 ± 0.08 ab | 0.76 ± 0.02 a | 0.89 ± 0.02 a |

| V2 (Low-input) | 27.00 ± 0.82 b | 2.75 ± 0.05 a | 0.84 ± 0.01 a | 0.91 ± 0.01 a |

| V3 (Medium-input) | 22.50 ± 1.29 c | 2.48 ± 0.06 b | 0.80 ± 0.03 a | 0.88 ± 0.01 a |

| V4 (High-input) | 17.25 ± 0.50 d | 1.62 ± 0.14 c | 0.57 ± 0.05 b | 0.63 ± 0.05 b |

| V5 (Organic-mineral) | 18.25 ± 0.50 cd | 2.38 ± 0.03 b | 0.82 ± 0.01 a | 0.87 ± 0.01 a |

| F test | 239.72 | 128.01 | 73.68 | 85.37 |

| pValue | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

The results highlight the major impact of fertilization type and intensity on the structure and diversity of mountain grasslands, confirming an ecological transition from oligotrophic communities toward mesotrophic and eutrophic grassland types. The MRPP, PCoA, ISA analyses and the diversity indices consistently describe the same trophic gradient driven by progressive fertilization. The following

Section 3 addresses the ecological mechanisms underlying these changes and compares the present findings with observations reported for other European mountain ecosystems. These results form the foundation for the ecological interpretation presented in the

Section 3.

3. Discussion

The results obtained in this study demonstrate that organo-mineral fertilization can represent an effective management strategy for balancing productivity and biodiversity in HNV mountain grasslands of the Apuseni Mountains when applied at appropriate intensity levels. Analyses of floristic composition, diversity indices, and community structure revealed clear contrasts between high mineral input variants, which promoted biomass production at the expense of species diversity, and combined organo-mineral treatments. In particular, the medium-input treatment (V3) maintained moderate productivity while preserving relatively high species richness and Shannon diversity, as the addition of organic matter mitigated the dominance of competitive grasses and reduced the negative impacts of intensive fertilization on grassland vegetation. By comparison, low-input fertilization (V2) primarily supported biodiversity conservation but provided limited productivity gains, underscoring the importance of intermediate fertilization rates in achieving a measurable trade-off between ecosystem services.

3.1. The Effects of Fertilization on Floristic Composition and Diversity

Cluster analysis (Sørensen–Bray–Curtis index, UPGMA method) revealed five distinct plant groups, corresponding to a clear trophic gradient determined by fertilization intensity. The succession of these types illustrates the transformation of mountain grasslands under the influence of applied management, from stable oligotrophic stages to eutrophic communities characterized by the dominance of nitrophilic species and reduced floristic diversity, which is useful information for the conservation of biodiversity and the sustainability of HNV mountain ecosystems.

The dominance of

Festuca rubra in unfertilized treatments reflects the ecological stability of oligotrophic mountain grasslands maintained under long-term extensive management [

65]. Such communities are widely described in the literature as biodiversity-rich systems shaped by low nutrient availability and the prevalence of stress-tolerant perennial species [

98,

99]. Their persistence under zero-input conditions highlights the strong link between nutrient limitation and the maintenance of high floristic diversity, as additional fertilization is known to disrupt competitive balances and favor nutrient-demanding species [

100,

101]. In this context,

Festuca rubra–dominated grasslands can be interpreted as conservation-oriented ecological states, characterized by stable species composition and high floristic diversity, indicative of favorable conditions for biodiversity conservation and habitat integrity. Rather than reflecting merely low-productivity systems, these grasslands represent semi-natural communities of high natural value, shaped by long-term low-intensity management and limited nutrient inputs [

102,

103,

104,

105].

The coexistence of

Agrostis capillaris and

Festuca rubra under moderate organic fertilization reflects a transitional ecological state between oligotrophic and mesotrophic grassland conditions. The increased cover of

Agrostis capillaris, while

Festuca rubra remains codominant, suggests that moderate nutrient inputs can alter competitive relationships without disrupting the overall structural integrity of the community. Such grassland types are characteristic of the Apuseni Natural Park and are widely distributed within the region [

74]. From a functional perspective, moderate organic fertilization has been shown to enhance functional diversity and improve forage availability while maintaining ecological stability [

106], thereby preserving the defining features of habitat 6520—Mountain Meadows [

107]. These findings support the broader view that low-input organic fertilization can represent an effective management strategy for enhancing productivity in HNV grasslands without triggering substantial biodiversity loss [

11,

39,

108].

Grassland communities developing under moderate organo-mineral fertilization reflect a balanced ecological response in which productivity gains are achieved without disrupting floristic structure. The coexistence of

Agrostis capillaris,

Trisetum flavescens, and

Alchemilla vulgaris indicates mesotrophic conditions that support both forage production and species diversity. Similar vegetation types have been reported in actively managed mountain hay meadows under moderate fertilization regimes, where ecological stability is maintained despite increased nutrient availability [

109,

110]. In this context,

Alchemilla vulgaris is widely recognized as an indicator of mesotrophic and ecologically stable habitats [

111,

112], suggesting that nutrient inputs and interspecific competition remain within an optimal range. Such mesophilic mountain grasslands represent systems in which trophic inputs are sufficiently high to enhance productivity but not excessive enough to trigger competitive exclusion [

19,

113]. The observed vegetation responses under moderate organo-mineral fertilization are in line with general trends reported in the literature, which associate moderate nutrient inputs with improved forage quality and dry matter production in mountain grasslands [

44,

73], supporting the role of this management regime as an effective compromise between agricultural productivity and biodiversity conservation in High Nature Value systems.

In contrast, grasslands receiving exclusively mineral fertilization exhibit a pronounced shift in community structure toward dominance by

Agrostis capillaris, accompanied by floristic simplification and increased abundance of nitrophilous species. Such patterns have been consistently documented in mineral-fertilized mountain grasslands and are characteristic of ecosystems exposed to high nitrogen availability [

11,

39,

65]. Under these conditions, fast-growing competitive grasses tend to outcompete dicotyledons and species adapted to oligotrophic environments, leading to homogenization of plant communities [

114]. Although mineral fertilization may enhance short-term productivity, these changes illustrate its adverse implications for long-term ecological sustainability and the conservation value of HNV grasslands.

At the highest fertilization intensities, grassland communities become increasingly dominated by highly productive mesophilic species, with

Centaurea pseudophrygia emerging as a codominant element indicative of eutrophic conditions [

115,

116]. Such communities are characterized by reduced species richness and a more uniform floristic diversity, in line with observations from other intensively fertilized European mountain grasslands [

37,

117]. The sequence of vegetation responses identified across fertilization treatments thus highlights a clear trophic gradient: moderate organo-mineral inputs maintain ecological balance and floristic diversity, whereas exclusive mineral fertilization and high input levels lead to biodiversity loss and a decline in the ecological value of mountain grasslands.

The contrasting vegetation patterns observed under different fertilization regimes highlight the role of nutrient form and intensity in shaping mountain grassland stability. Mineral-only fertilization promotes floristic simplification by favoring competitive grass species and reducing the presence of oligotrophic taxa typical of nutrient-poor mountain grasslands [

72]. Such responses are widely documented and reflect the tendency of high nitrogen inputs to reduce species richness and generate less resilient plant communities with limited resistance to environmental stress [

88,

118]. In contrast, organo-mineral fertilization supports a more complex and functionally diverse floristic structure, characterized by the persistence of valuable perennial species such as

Trifolium repens,

Lotus corniculatus,

Alchemilla vulgaris, and

Carex pallescens, which are commonly associated with moderate-input management systems. This pattern aligns with observations from Transylvanian grasslands [

38], where mixed fertilization has been shown to enhance ecological stability by maintaining balanced proportions of leguminous and mesotrophic species [

69,

119]. The higher values of Shannon and Simpson diversity indices under organo-mineral treatments further suggest that reduced reliance on mineral inputs contributes to greater α-diversity and ecosystem stability, supporting the view that combining organic amendments with lower chemical inputs promotes more even and resilient plant communities [

82,

120].

3.2. Ecological Mechanisms and Responses to Organo-Mineral Fertilization

The application of organo-mineral fertilization is widely recognized to influence soil biological functioning and nutrient dynamics through mechanisms reported in previous studies. Although soil microbial parameters were not directly measured in the present study, the observed vegetation responses under combined treatments are consistent with literature indicating that organic inputs can indirectly support nutrient availability and soil functioning by improving soil structure and substrate supply. Therefore, the potential effects on soil biological processes discussed here are interpreted in the context of existing studies rather than as direct experimental evidence from this research [

66,

84]. The increase in stable organic matter and the gradual release of nutrients contribute to a more balanced nutrient supply, preventing excessive nutrient accumulation and limiting soil structural degradation [

106,

121]. These processes reduce the risk of competitive exclusion driven by abrupt increases in nutrient availability and help explain the higher species diversity observed under combined fertilization regimes [

37,

70].

In addition to belowground effects, moderate nutrient availability influences aboveground competitive interactions by limiting excessive biomass production and canopy closure. This reduces light-mediated competition, allowing the persistence of low-growing and stress-tolerant species that are typically excluded under high nutrient conditions [

71]. Organic matter inputs further enhance soil water-holding capacity and nutrient retention, buffering plant communities against climatic stress and reducing interannual variability in productivity [

122,123].

In contrast, exclusively mineral fertilization, although effective in increasing short-term productivity, often leads to rapid nutrient availability, intensified competition for light, and shifts toward dominance by fast-growing species [

37]. Such changes promote trophic imbalance and reduce ecosystem resilience, ultimately resulting in simplified floristic structures and diminished ecological stability [

80,

123]. Overall, these findings support the concept of a functional compromise, whereby organo-mineral fertilization systems maintain adequate productivity while preserving ecosystem services and floristic diversity in mountain grasslands.

3.3. Comparison with Other Studies from the European Mountain Region

The effects of organo-mineral fertilization on the floristic structure observed in the Apuseni Mountains grasslands are consistent with trends reported in the Alpine and Carpathian regions [

45,

98]. In these areas, the combination of farmyard manure with moderate mineral inputs has maintained high species diversity and a significant proportion of legume species, ensuring a stable pastoral value. At the same time, long-term studies from Transylvania [

38,

96,

124] show that combined fertilization has generated a steady increase in productivity without the loss of species sensitive to eutrophication, confirming the ecological buffering effect provided by organic matter [

125]. Our results complement these observations, demonstrating that organo-mineral inputs can be adapted to avoid critical thresholds of intensification that lead to the collapse of diversity.

3.4. Implications for the Management of High Nature Value (HNV) Grasslands

From a practical perspective, the results show that moderate organo-mineral fertilization can be effectively integrated into traditional agro-pastoral systems in the Apuseni Mountains, in line with adaptive management principles. The combined use of manure and moderate mineral inputs (below 100 kg N ha

−1 year

−1) complies with the Nitrates Directive and Natura 2000 requirements, supporting the maintenance of habitats of Community interest such as

Festuco-Brometalia and

Nardus stricta grasslands. Organo-mineral systems therefore contribute to sustainable mountain agriculture by balancing production, biodiversity conservation, and resilience to climate change [

67,

71,

126,

127].

Moderate organo-mineral fertilization (≤10 t ha

−1 manure combined with N

50P

25K

25) maximizes pastoral value without compromising floristic diversity, ensuring both productivity and community stability [

37,

38]. In contrast, mineral fertilization exceeding 100 kg N ha

−1 promotes eutrophication, favors nitrophilic species, and reduces species of conservation interest, highlighting the need to limit high input levels. Applying organo-mineral fertilizers mainly in spring improves nitrogen use efficiency by reducing leaching and volatilization, while the use of locally sourced organic fertilizers supports natural nutrient cycles and soil structure. Integrating these practices into Natura 2000 management plans facilitates compliance with EU policies and contributes to the objectives of the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 [

128,

129,

130].

Beyond the descriptive patterns observed, the responses of grassland vegetation to fertilization intensity can be explained by well-established ecological mechanisms related to nutrient availability and competitive interactions among plant species. Increased mineral nutrient inputs favor fast-growing, competitive grasses, leading to asymmetric competition for light and a progressive exclusion of less competitive forbs, which explains the reduced species richness under high-input variants. In contrast, the inclusion of organic matter under organo-mineral fertilization likely moderated nutrient release and enhanced spatial and temporal heterogeneity, thereby reducing competitive dominance and allowing the persistence of a more diverse plant community. These mechanisms are consistent with the observed shifts in floristic diversity and community structure along the fertilization gradient and with previous findings from semi-natural mountain grasslands managed under low to moderate input regimes.

While previous studies have documented the effects of organic or mineral fertilization on grassland diversity, most have focused on short- to medium-term responses or on single input types. The present study extends this body of literature by providing evidence from a 15-year long-term experiment that explicitly integrates organic, mineral, and combined organo-mineral fertilization regimes within the same experimental framework. By identifying fertilization thresholds that balance productivity and biodiversity in High Nature Value mountain grasslands, our results offer a more nuanced understanding of how fertilization intensity and nutrient form jointly shape floristic diversity over extended time scales.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. The experiment was conducted at a single site, which may restrict the direct extrapolation of the results to other mountain grassland systems. Although climatic variability can influence grassland dynamics, the present study focuses exclusively on the long-term effects of fertilization gradients under comparable climatic conditions, allowing a clear isolation of fertilization-driven effects on floristic diversity and biodiversity. Future multi-site studies could further explore interactions between fertilization and climatic variability.