Effects of Exogenous Phosphorus and Hydrogen Peroxide on Wheat Root Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Biomass

2.2. P Concentration in Shoots

2.3. Root Traits

2.4. ROS Distribution in the Roots

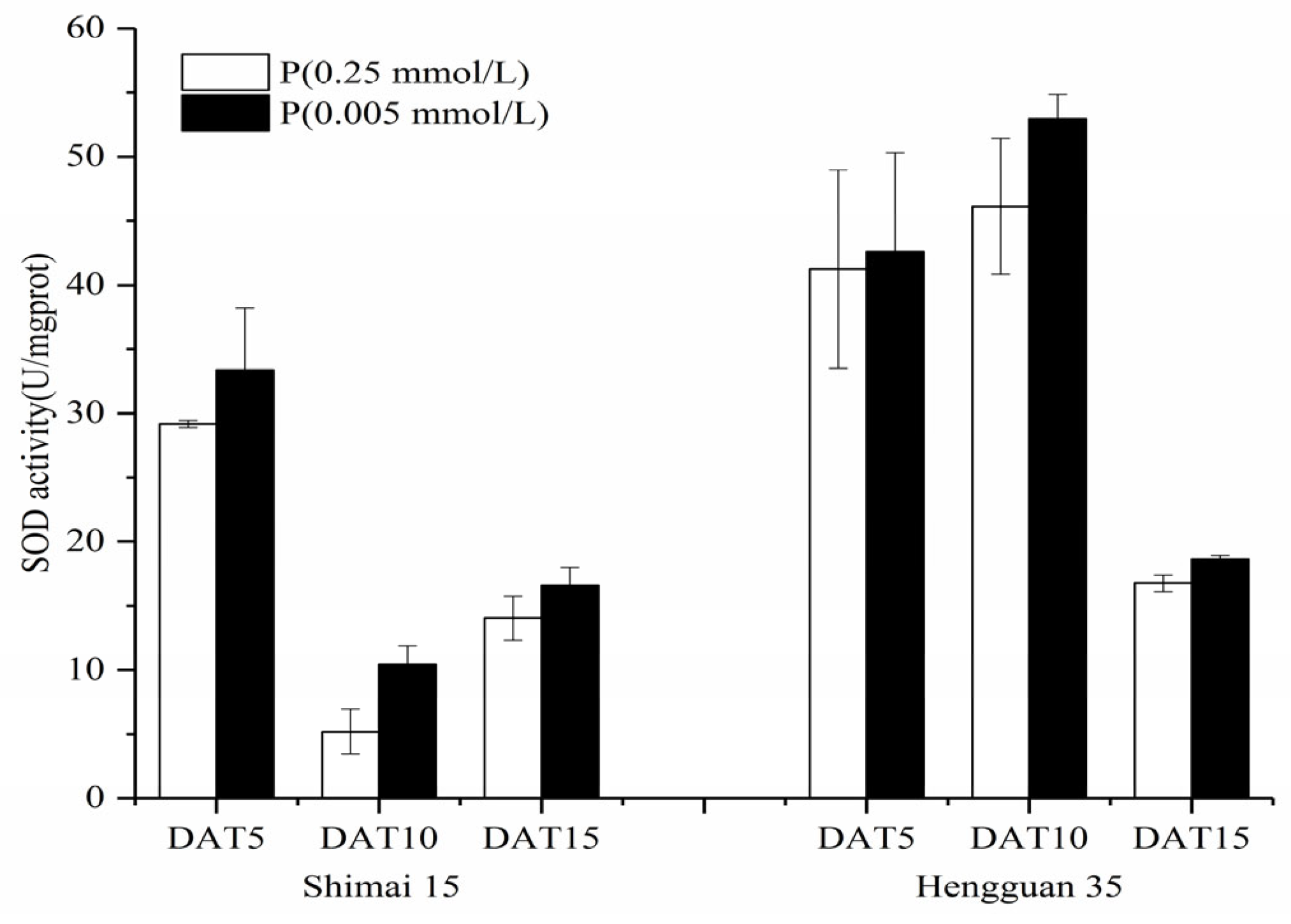

2.5. SOD, POD, and CAT Activities in the Roots

3. Discussion

3.1. P Deficiency Affects the Root Growth of Wheat Seedlings

3.2. P Deficiency Affects ROS Distribution in Distal Parts of Wheat Roots

3.3. P Deficiency Affects SOD, POD, and CAT Activity in Roots of Wheat Seedlings

3.4. Concentration-Dependent Roles of H2O2 in Modulating Wheat Root Architecture Under Low P

3.5. Potential Interactions with Other Reactive Molecular Species

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growing Environment

4.2. Treatments

4.3. Determination of Biomass and Phosphorus Content

4.4. Determination of Root Development

4.5. Histochemical Localization of H2O2 with Fluorescein Staining

4.6. Determination of Activities of SOD, POD and CAT

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lambers, H. Phosphorus acquisition and utilization in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerke, J. Improving phosphate acquisition from soil via higher plants while approaching peak phosphorus worldwide: A critical review of current concepts and misconceptions. Plants 2024, 13, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A.; Berta, G.; Doussan, C.; Merchan, F.; Crespi, M. Plant root growth, architecture and function. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 153–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.S.; Chiang, C.P.; Leong, S.J.; Chiou, T.J. Sensing and signaling of phosphate starvation: From local to long distance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1714–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Shulaev, V.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Ciani, S.; Schachtman, D.P. A peroxidase contributes to ROS production during Arabidopsis root response to potassium deficiency. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, A.C.; Fluhr, R. Two distinct sources of elicited reactive oxygen species in tobacco epidermal cells. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyburski, J.; Dunajska, K.; Tretyn, A. Reactive oxygen species localization in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings grown under phosphate deficiency. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 59, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyburski, J.; Dunajska, K.; Tretyn, A. A role for redox factors in shaping root architecture under phosphorus deficiency. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, R.; Berg, R.H.; Schachtman, D.P. Reactive oxygen species and root hairs in Arabidopsis root response to nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium deficiency. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Toev, T.; Heisters, M.; Teller, J.; Moore, K.L.; Hause, G.; Dinesh, D.C.; Bürstenbinder, K.; Abel, S. Iron-dependent callose deposition adjusts root meristem maintenance to phosphate availability. Dev. Cell 2015, 33, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehenwarter, W.; Mönchgesang, S.; Neumann, S.; Majovsky, P.; Abel, S.; Müller, J. Comparative expression profiling reveals a role of the root apoplast in local phosphate response. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juszczuk, I.; Malusà, E.; Rychter, A.M. Oxidative stress during phosphate deficiency in roots of bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2001, 158, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malusà, E.; Laurenti, E.; Juszczuk, I.; Ferrari, R.P.; Rychter, A.M. Free radical production in roots of Phaseolus vulgaris subjected to phosphate deficiency stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Arredondo, D.L.; Leyva-González, M.A.; González-Morales, S.I.; López-Bucio, J.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Phosphate nutrition: Improving low-phosphate tolerance in crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Ceasar, S.A.; Palmer, A.J.; Paterson, J.B.; Qi, W.; Muench, S.P.; Baldwin, S.A. Replace, reuse, recycle: Improving the sustainable use of phosphorus by plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3523–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Bi, H.H.; Cheng, X.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Run, Y.H.; Wang, H.H.; Mao, P.J.; Li, H.X.; Xu, H.X. Genome-wide association study of low-phosphorus tolerance related traits in wheat. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2020, 21, 431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Soumya, P.R.; Sharma, S.; Meena, M.K.; Pandey, R. Response of diverse bread wheat genotypes in terms of root architectural traits at seedling stage in response to low phosphorus stress. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2021, 26, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmateja, P.; Yadav, R.; Kumar, M.; Babu, P.; Jain, N.; Mandal, P.K.; Pandey, R.; Shrivastava, M.; Gaikwad, K.B.; Bainsla, N.K.; et al. Genome-wide association studies reveal putative QTLs for physiological traits under contrasting P conditions in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 984720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.M.; Blackwell, M.; Mcgrath, S.; George, T.S.; Granger, S.H.; Hawkins, J.M.B.; Dunham, S.; Shen, J.B. Morphological responses of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) roots to phosphorus supply in two contrasting soils. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 154, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Wen, Z.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Miao, Y.; Shen, J. The responses of root morphology and phosphorus-mobilizing exudations in wheat to increasing shoot phosphorus concentration. AoB Plants 2018, 10, ply054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, H. The distribution and productivity of fine roots in boreal forests. Plant Soil 1983, 71, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Li, K.; Yan, S.; Qu, X.; Zhang, J. Phosphate starvation of maize inhibits lateral root formation and alters gene expression in the lateral root primordium zone. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.G.; Zhang, F.S.; Yang, J.F. Characteristics of root system of wheat seedlings and their relative grain yield. Acta Agric. Boreali Sin. 2001, 16, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Heppell, J.; Talboys, P.; Payvandi, S.; Zygalakis, K.C.; Fliege, J.; Withers, P.J.A.; Jones, D.L.; Roose, T. How changing root system architecture can help tackle a reduction in soil phosphate (P) levels for better plant P acquisition. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollier, A.; Pellerin, S. Maize root system growth and development as influenced by phosphorus deficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Marschner, P.; Rengel, Z. Effect of Internal and External Factors on Root Growth and Development. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Marschner, P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Meng, Y.L.; Feldman, L.J. Quiescent center formation in maize roots is associated with an auxin-regulated oxidizing environment. Development 2003, 130, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liszkay, A.; van der Zalm, E.; Schopfer, P. Production of reactive oxygen intermediates (O2•−, H2O2, and •OH) by maize roots and their role in wall loosening and elongation growth. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3114–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Wang, Z.W.; Wan, J.X.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.R.; Li, G.X.; Shen, R.F.; Zheng, S.J. Pectin enhances rice (Oryza sativa) root phosphorus remobilization. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Zhu, C.Q.; Zhao, X.S.; Zheng, S.J.; Shen, R.F. Ethylene is involved in root phosphorus remobilization in rice (Oryza sativa) by regulating cell-wall pectin and enhancing phosphate translocation to shoots. Ann. Bot. 2016, 118, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Identification of Phosphate Starvation Regulated Cell Wall Proteins in Soybean Roots and Functional Characterization of GmPAP1-like. Ph.D. Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Gao, Z.; Shi, Q.; Gong, B. SAMS1 stimulates tomato root growth and P availability via activating polyamines and ethylene synergetic signaling under low-P condition. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 197, 104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potikha, T.S.; Collins, C.C.; Johnson, D.I.; Delmer, D.P.; Levine, A. The involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the differentiation of secondary walls in cotton fibers. Plant Physiol. 1999, 119, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, G.; Doonan, J.H. Cyclin dependent protein kinases and stress responses in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnayake, M.; Leonard, R.T.; Menge, J.A. Root exudation in relation to supply of phosphorus and its possible relevance to mycorrhizal formation. New Phytol. 1978, 81, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.R.; Yao, P.C.; Zhang, Z.D.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, M. Involvement of antioxidative defense system in rice seedlings exposed to aluminum toxicity and phosphorus deficiency. Rice Sci. 2012, 19, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, J.G.; Pandya, R.V.; Thaker, V.S. Changes in radical scavenging activity of normal, endoreduplicated and depolyploid root tip cells of Allium cepa. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1538–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukagoshi, H.; Busch, W.; Benfey, P.N. Transcriptional regulation of ROS controls transition from proliferation to differentiation in the root. Cell 2010, 143, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passardi, F.; Tognolli, M.; De Meyer, M.; Penel, C.; Dunand, C. Two cell wall associated peroxidases from Arabidopsis influence root elongation. Planta 2006, 223, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzergue, C.; Dartevelle, T.; Godon, C.; Laugier, E.; Meisrimler, C.; Teulon, J.M.; Creff, A.; Bissler, M.; Brouchoud, C.; Hagège, A.; et al. Low phosphate activates STOP1-ALMT1 to rapidly inhibit root cell elongation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Hu, P.; Li, C.; Hao, F.S. AtrbohD and AtrbohF negatively regulate lateral root development by changing the localized accumulation of superoxide in primary roots of Arabidopsis. Planta 2015, 241, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Xue, L.; Xu, S.; Feng, H.; An, L. Hydrogen peroxide involvement in formation and development of adventitious roots in cucumber. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 52, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.W.; Xue, L.; Xu, S.; Feng, H.; An, L. Hydrogen peroxide acts as a signal molecule in the adventitious root formation of mung bean seedlings. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 65, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.X.; Zhang, W.H.; Liu, Y.L. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide generated by polyamine oxidative degradation in the development of lateral roots in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2006, 48, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, K.; Maki, H.; Itaya, T.; Suzuki, T.; Nomoto, M.; Sakaoka, S.; Morikami, A.; Higashiyama, T.; Tada, Y.; Busch, W.; et al. MYB30 links ROS signaling, root cell elongation, and plant immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E4710–E4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunand, C.; Crèvecoeur, M.; Penel, C. Distribution of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in Arabidopsis root and their influence on root development: Possible interaction with peroxidases. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, C.; Pallero-Baena, M.; Casimiro, I.; De Rybel, B.; Orman-Ligeza, B.; Van Isterdael, G.; Beeckman, T.; Draye, X.; Casero, P.; Del Pozo, J.C. The emerging role of reactive oxygen species signaling during lateral root development. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukagoshi, H. Defective root growth triggered by oxidative stress is controlled through the expression of cell cycle-related genes. Plant Sci. 2012, 197, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, Ł.P.; Signorelli, S.; Considine, M.J.; Montrichard, F. Integration of reactive oxygen species and nutrient signalling to shape root system architecture. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.G.; Min, X.; Zhou, Z.H. Hydrogen sulfide: A signal molecule in plant cross-adaptation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatro, A.; Ramos-Artuso, F.; Luquet, M.; Buet, A.; Simontacchi, M. An update on nitric oxide production and role under phosphorus scarcity in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S. Role of Nitric Oxide as a Double Edged Sword in Root Growth and Development. In Rhizobiology: Molecular Physiology of Plant Roots; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 167–193. [Google Scholar]

- Alvi, A.F.; Iqbal, N.; Albaqami, M.; Khan, N.A. The emerging key role of reactive sulfur species in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e13945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Role of Glutathione in Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. In Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen and Sulfur Species in Plants: Production, Metabolism, Signaling and Defense Mechanisms; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2019; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.L.; Buettner, G.R.; O’Malley, Y.Q.; Wessels, D.A.; Flaherty, D.M. Dihydrofluorescein diacetate is superior for detecting intracellular oxidants: Comparison with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, 5(and 6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, and dihydrorhodamine 123. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chance, B.; Maehly, A.C. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. In Methods in Enzymology; Colowick, S.P., Kaplan, N.O., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1955; Volume II, pp. 764–775. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Shoot Biomass (g/Plant) | Root Biomass (g/Plant) | Root/Shoot Ratio | P Concentration in Shoots (mg/g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (mmol/L) | H2O2 (mmol/L) | AsA (mmol/L) | DPI (μmol/L) | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 |

| 0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.132 | 0.131 | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 232.45 | 231.27 |

| 2.5 | 0 | 0.102 | 0.101 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 234.58 | 225.01 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 0.07 | 0.091 | 0.017 | 0.023 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 269.62 | 216.67 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.093 | 0.106 | 0.037 | 0.041 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 256.18 | 190.63 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 0.084 | 0.102 | 0.023 | 0.032 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 241.95 | 226.18 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.083 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 216.99 | 200.38 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.082 | 0.093 | 0.018 | 0.026 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 276.01 | 243.89 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 0.076 | 0.075 | 0.051 | 0.057 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 257.73 | 280.82 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 0.083 | 0.088 | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 220.38 | 182.42 | ||

| 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.192 | 0.202 | 0.039 | 0.044 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 962.99 | 916.1 |

| 2.5 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.105 | 0.029 | 0.027 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 437.72 | 487.54 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 0.074 | 0.089 | 0.017 | 0.022 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 462.84 | 439.78 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.146 | 0.138 | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 806.75 | 786.86 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 0.108 | 0.12 | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 497.59 | 487.52 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 0.107 | 0.094 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.26 | 0.3 | 323.35 | 352.38 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.084 | 0.096 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 616.52 | 523.95 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.087 | 0.056 | 0.058 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 597.07 | 574.69 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 0.095 | 0.093 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 324.2 | 334.54 | ||

| LSD (p < 0.05) | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 65.56 | 64.00 | |||

| Treatments | Number of Nodal Roots (NO.) | Total Root Length (cm) | Root Length Density (cm/g) | Primary Root Length (cm) | Lateral Root Length (cm) | Lateral Root Density (NO./cm) | Average Lateral Root Length (cm) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (mmol/L) | H2O2 (mmol/L) | AsA (mmol/L) | DPI (μmol/L) | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 | SM15 | HG35 |

| 0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 918.6 | 903.7 | 20,424.7 | 19,151.7 | 31.1 | 29.4 | 706.1 | 719.6 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 4.3 | 3.9 |

| 2.5 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 254.9 | 249.5 | 13,319.1 | 11,846.7 | 21.7 | 18.6 | 131.5 | 144.8 | 0.63 | 0.86 | 1.7 | 1.7 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 229.7 | 275.3 | 11,443.4 | 9049.5 | 18.6 | 19.4 | 127.8 | 172.8 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 1.7 | 2.1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 338.7 | 348.8 | 9138.0 | 8466.5 | 25.2 | 25.6 | 184.9 | 206 | 1.31 | 1.53 | 0.9 | 1 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 238.4 | 281.1 | 9141.5 | 9102.8 | 19.7 | 20 | 127.4 | 173.3 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 2.1 | 2.4 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 256.7 | 256.6 | 10,354.1 | 8830.6 | 20.8 | 19.6 | 137.3 | 151.6 | 1.1 | 1.38 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 221.0 | 252.4 | 12,600.3 | 9906.7 | 19.7 | 20.5 | 108.4 | 134.2 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 9 | 8 | 295.2 | 305.3 | 11,393.5 | 10,071.7 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 171.8 | 194.6 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 2.4 | 2.6 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 253.6 | 243.1 | 5751.1 | 5351.1 | 20.1 | 17.6 | 136.4 | 140.4 | 1.1 | 1.22 | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 875.5 | 941.2 | 22,272.7 | 21,620.1 | 26.4 | 24.8 | 681.2 | 770.8 | 1.09 | 1.36 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| 2.5 | 0 | 10 | 7 | 287.1 | 249.5 | 11,563.5 | 12,123.1 | 20.8 | 17 | 149.3 | 150.2 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 1.7 | 1.9 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 191.9 | 263.7 | 9829.9 | 9116.7 | 17.1 | 18.1 | 93.9 | 168 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 1.8 | 2.1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 404.2 | 411.2 | 10,246.7 | 9682.7 | 23.3 | 25.3 | 232.6 | 255 | 1.58 | 1.77 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 294 | 261.8 | 9157.0 | 8975.7 | 20.2 | 15.1 | 166.8 | 165 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 2.4 | 2.4 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 11 | 8 | 259.2 | 252 | 11,664.9 | 8945.5 | 19.5 | 19.2 | 137.7 | 150.7 | 0.96 | 1.24 | 1.2 | 1.2 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 11 | 257.5 | 217 | 11,434.8 | 10,082.5 | 19.2 | 18 | 136.8 | 124.8 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 1.4 | 1.3 | |

| 2.5 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 336.3 | 301.4 | 10,698.9 | 10,499.5 | 20.5 | 17.3 | 193.5 | 188.2 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 2.7 | 2.9 | ||

| 0 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 268.4 | 258.4 | 6122.0 | 5249.3 | 21.2 | 17.8 | 140.5 | 154 | 1.12 | 1.38 | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| LSD (p < 0.05) | 2 | 1 | 62.6 | 61.7 | 1477.9 | 1034.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 54.4 | 52.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of Exogenous Phosphorus and Hydrogen Peroxide on Wheat Root Architecture. Plants 2026, 15, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020253

Chen L, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Wang H. Effects of Exogenous Phosphorus and Hydrogen Peroxide on Wheat Root Architecture. Plants. 2026; 15(2):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020253

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lei, Lei Zhou, Yuwei Zhang, and Hong Wang. 2026. "Effects of Exogenous Phosphorus and Hydrogen Peroxide on Wheat Root Architecture" Plants 15, no. 2: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020253

APA StyleChen, L., Zhou, L., Zhang, Y., & Wang, H. (2026). Effects of Exogenous Phosphorus and Hydrogen Peroxide on Wheat Root Architecture. Plants, 15(2), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15020253