Transcriptomic Analysis of Rice (Jijing129) Reveals Growth and Gene Expression Responses to Different Red-Blue Laser Light Treatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

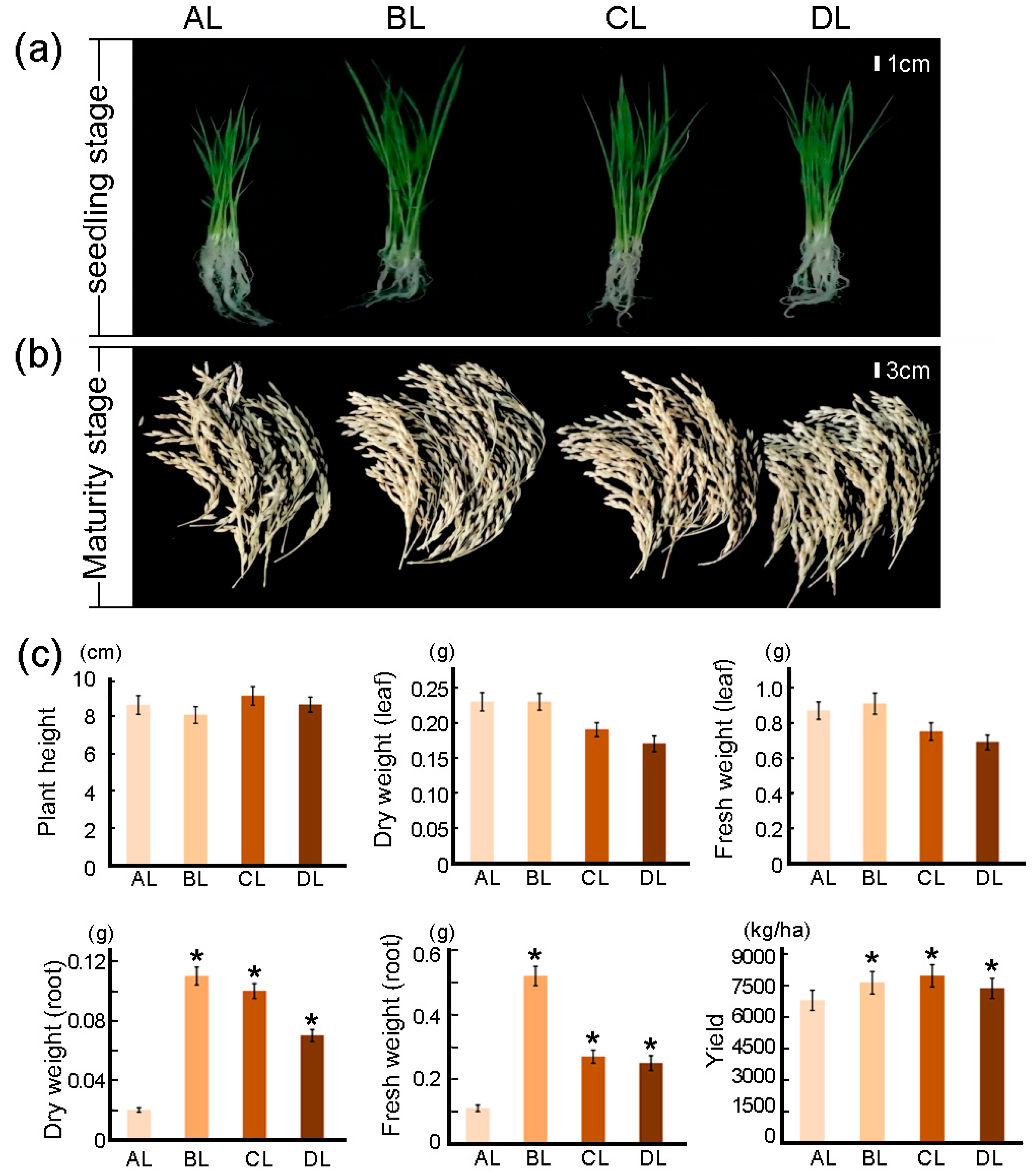

2.1. Effects of Short-Term Laser Irradiation on Root Morphology and Yield in Rice

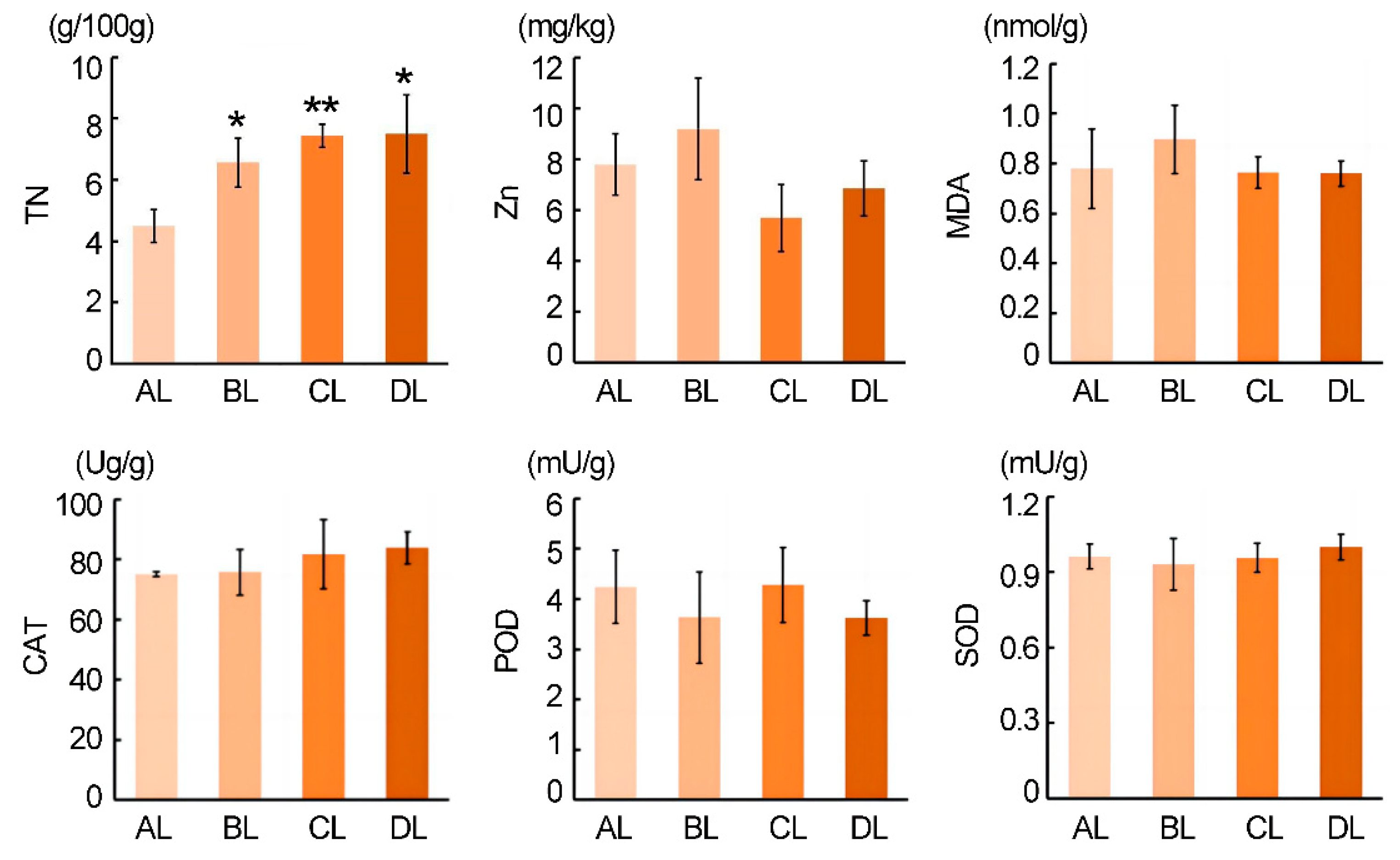

2.2. Effect of Short-Term Laser Irradiation on the Small Organic Compounds Content in Rice

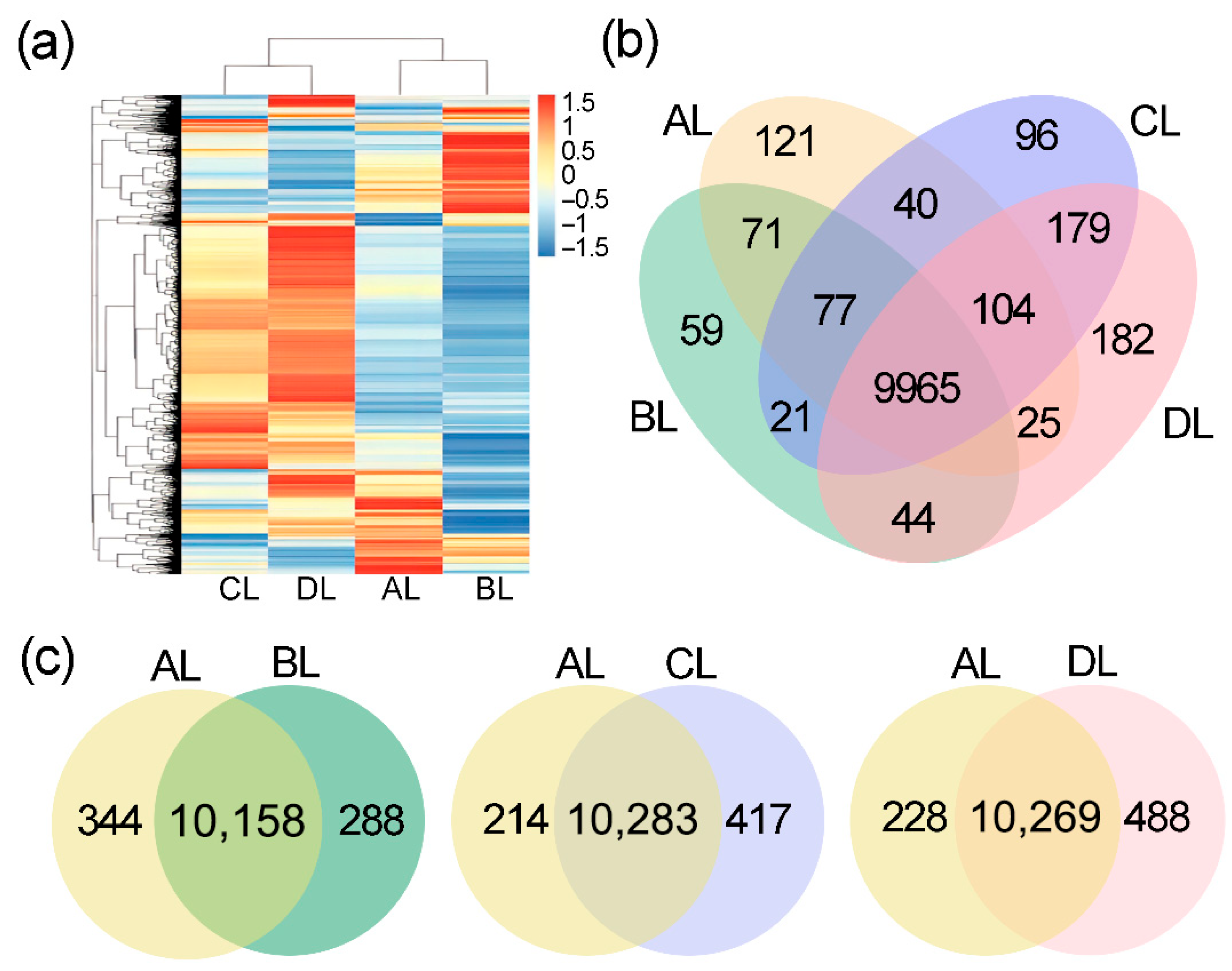

2.3. Effects of Short-Term Laser Irradiation on Genome-Wide Gene Expression in Rice

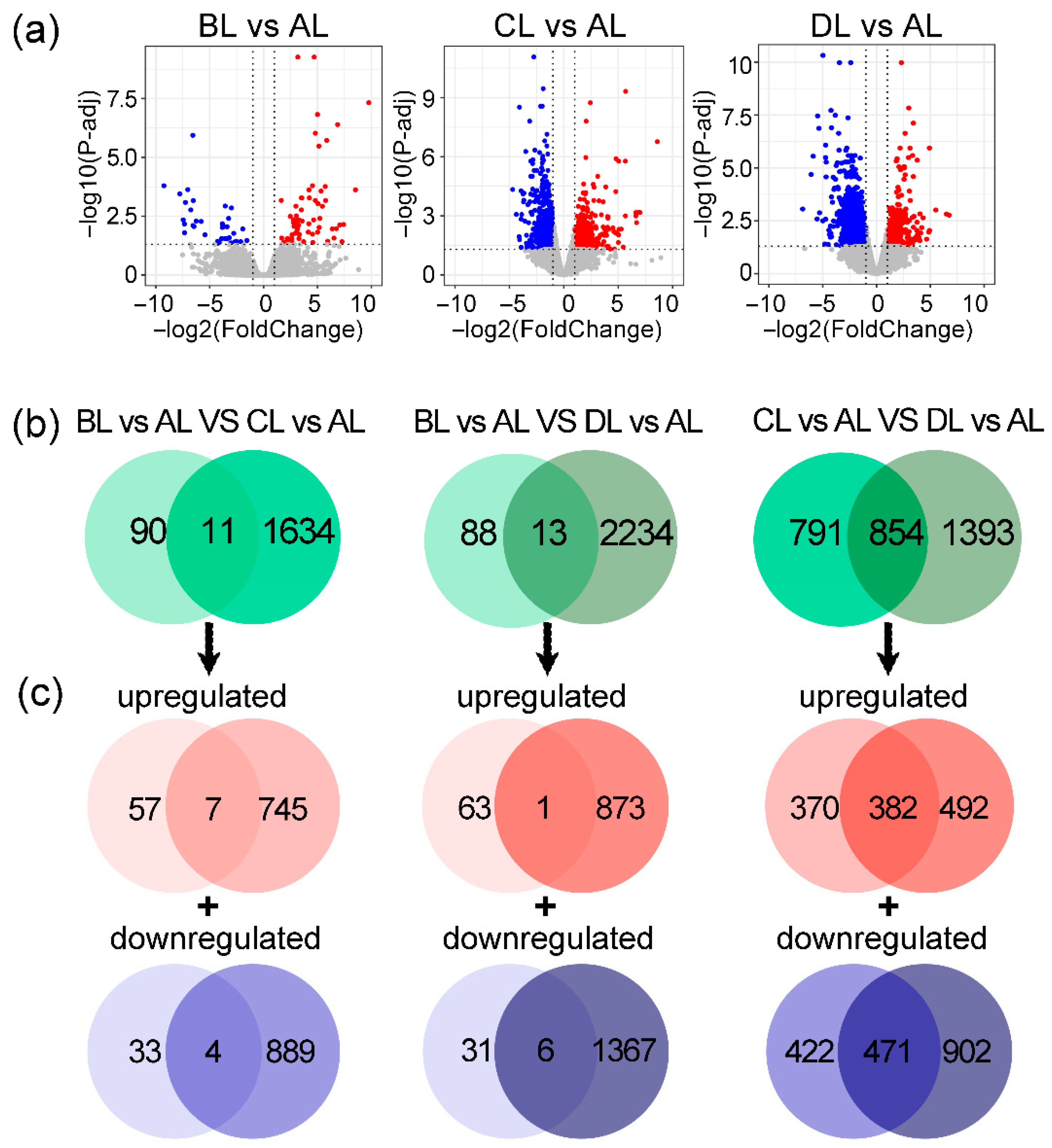

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes in Rice Under Laser Irradiation

2.5. Comparative Analysis of GO and KEGG Enrichment in Rice Under Laser Irradiation

2.6. Laser Irradiation Differentially Regulates Nitrogen-Related Genes

2.7. Laser Irradiation Differentially Regulates Photosynthesis-Related Gene Expression in Rice

2.8. Laser Irradiation Differentially Regulates Rice Genes Associated with Physical Characteristics

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.2. Determination of Small Organic Compounds, Enzyme Activity, and SOD and POD Activity

4.3. RNA Extraction and Sequencing

4.4. Identification and Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

4.5. qRT-PCR Validation

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, Y.; Lei, Y.; Ahmed, T.; Cheng, F.; Lei, K.; Yang, H.; Ali, H.M.; Li, Z.; Qi, X. Low-intensity laser exposure enhances rice (Oryza sativa L.) growth through physio-biochemical regulation, transcriptional modulation, and microbiome alteration. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, A.; Wong, A.; Ng, T.K.; Marondedze, C.; Gehring, C.; Ooi, B.S. Growth and development of Arabidopsis thaliana under single-wavelength red and blue laser light. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Polutchko, S.K.; Stewart, J.J.; Adams, W.W., III. History of excess-light exposure modulates the extent and kinetics of fast-acting non-photochemical energy dissipation. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2022, 27, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.C.; Dominguez, P.A.; Cruz, O.A.; Ivanov, R.; Carballo, C.A.; Zepeda, B.R. Laser in agriculture. Int. Agrophys. 2010, 24, 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Nadimi, M.; Sun, D.W.; Paliwal, J. Recent applications of novel laser techniques for enhancing agricultural production. Laser Phys. 2021, 31, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Elsaoud, A.M.; Tuleukhanov, S.T. Can He-Ne laser induce changes in oxidative stress and antioxidant activities of wheat cultivars from Kazakhstan and Egypt. Sci. Int. 2013, 1, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, C.; Valastro, S.; Calogero, G.; Smecca, E.; Mannino, G.; Arena, V.; Balestrini, R.; Sillo, F.; Ciná, L.; La Magna, A.; et al. Improved radicchio seedling growth under CsPbI3 perovskite rooftop in a laboratory-scale greenhouse for Agrivoltaics application. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liscum, E.; Hodgson, D.W.; Campbell, T.J. Blue light signaling through the cryptochromes and phototropins. So that’s what the blues is all about. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, J.M. Phototropin blue-light receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 58, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Liu, S.; Tang, C.; Mao, G.; Gai, P.; Guo, X.; Zheng, H.; Tang, Q. Photomorphogenesis and photosynthetic traits changes in rice seedlings responding to red and blue light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Liu, S.; Mao, G.; Tang, C.; Gai, P.; Guo, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, W.; Tang, Q. Simultaneous application of red and blue light regulate carbon and nitrogen metabolism, induces antioxidant defense system and promote growth in rice seedlings under low light stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, E.; Salo, R.; Lehtonen, E.; Aro, E.M. Regulation of D1-protein degradation during photoinhibition of photosystem II in vivo: Phosphorylation of the D1 protein in various plant groups. Planta 1995, 195, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Sun, H.; Rong, L.; Li, Z.; An, T.; Hu, W.; Ye, Z. Genotypic-dependent alternation in D1 protein turnover and PSII repair cycle in psf mutant rice (Oryza sativa L.), as well as its relation to light-induced leaf senescence. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 95, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, M.; Mattoo, A.K. D1-protein dynamics in photosystem II: The lingering enigma. Photosynth. Res. 2008, 98, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassi, M.; Ruberti, I.; Vernoux, T.; Xu, J. Shedding light on auxin movement: Light-regulation of polar auxin transport in the photocontrol of plant development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e23355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zažímalová, E.; Křeček, P.; Skůpa, P.; Hoyerová, K.; Petrášek, J. Polar transport of the plant hormone auxin–the role of PIN-FORMED (PIN) proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, H.; Liu, B.; Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, B. Response of Morphological Plasticity of Quercus variabilis Seedlings to Different Light Quality. Forests 2024, 15, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhzad, Y.; Babaei, A.; Yadollahi, A.; Kashkooli, A.B.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A.; Hesami, S. In vitro photomorphogenesis, plant growth regulators, melatonin content, and DNA methylation under various wavelengths of light in Phalaenopsis amabilis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2022, 149, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Nanseki, T.; Chomei, Y.; Kuang, J. A review of smart agriculture and production practices in Japanese large-scale rice farming. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Ouyang, Q.; Huang, S. The application of big data technology in the study of rice variety adaptability: Current status, challenges, and prospects. Resour. Data J. 2025, 4, 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.; Xiao, R.; Lyu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, R.; et al. Differential light-dependent regulation of soybean nodulation by papilionoid-specific HY5 homologs. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, E. Diversity and regulation of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in plants. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R543–R559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gai, S.; Su, L.; Tang, C.; Xia, M.; Zhou, Z. The antagonistic effects of red and blue light radiation on leaf and stem development of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seedlings. Plant Sci. 2025, 351, 112338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wonder, J.; Helming, T.; van Asselt, G.; Pantazopoulou, C.K.; van de Kaa, Y.; Kohlen, W.; Pierik, R.; Kajala, K. Brassinosteroid and gibberellin signaling are required for Tomato internode elongation in response to low red: Far-red light. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; You, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Ma, H.; Gong, J.; Sun, X. Red and blue light promote tomato fruit coloration through modulation of hormone homeostasis and pigment accumulation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 207, 112588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Shi, Q.; Yang, F.; Wei, M. Mixed red and blue light promotes ripening and improves quality of tomato fruit by influencing melatonin content. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 185, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra, M.L.F.; Serra, P.; Casati, P. Recent advances on the roles of flavonoids as plant protective molecules after UV and high light exposure. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, D.; Jiao, Z. Postharvest UV-C irradiation increased the flavonoids and anthocyanins accumulation, phenylpropanoid pathway gene expression, and antioxidant activity in sweet cherries (Prunus avium L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 175, 111490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Q.; Urano, D.; Wang, Z. Interactive effects of light quality and nitrate supply on growth and metabolic processes in two lettuce cultivars (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 213, 105443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellini, A.; Toscano, S.; Romano, D.; Ferrante, A. The role of blue and red light in the orchestration of secondary metabolites, nutrient transport and plant quality. Plants 2023, 12, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-x.; Bian, Z.-h.; Song, B.; Xu, H. Transcriptome analysis reveals the differential regulatory effects of red and blue light on nitrate metabolism in pakchoi (Brassica campestris L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, T.; Masabni, J.; Sun, L.; Niu, G. Effect of pre-harvest supplemental UV-A/Blue and Red/Blue LED lighting on lettuce growth and nutritional quality. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathy, P.S.; Kiran, K.R.; Joshi, M.B.; Mahato, K.K.; Muthusamy, A. He–Ne laser accelerates seed germination by modulating growth hormones and reprogramming metabolism in brinjal. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.X.; Schröder, W.P. The low molecular mass subunits of the photosynthetic supracomplex, photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2004, 1608, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, P.D. The ATP synthase—A splendid molecular machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997, 66, 717–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, J. Photosystem II: The engine of life. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2003, 36, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, G.U.Y.; Mulo, P. Plant type ferredoxins and ferredoxin-dependent metabolism. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Yu, H.; Zhou, L.; Qi, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; et al. Applications and Research Progress of Laser Technology in Agricultural Breeding. J. Jilin Agric. Univ. 2025, 47, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okla, M.K.; Abdel-Mawgoud, M.; Alamri, S.A.; Abbas, Z.K.; Al-Qahtani, W.H.; Al-Qahtani, S.M.; Al-Harbi, N.A.; Hassan, A.H.A.; Selim, S.; Alruhaili, M.H.; et al. Developmental stages-specific response of Anise plants to laser-induced growth, nutrients accumulation, and essential oil metabolism. Plants 2021, 10, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrig, A.; Najar, B.; Magdy Korany, S.; Hassan, A.H.; Alsherif, E.A.; Ali Shah, A.; Fahad, S.; Selim, S.; AbdElgawad, H. The interaction effect of laser irradiation and 6-Benzylaminopurine improves the chemical composition and biological activities of Linseed (Linum usitatissimum) sprouts. Biology 2022, 11, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, H.; Zhao, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. OsMYB3 is a R2R3-MYB gene responsible for anthocyanin biosynthesis in black rice. Mol. Breed. 2021, 41, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, F.; Gao, J.; Galbraith, D.W.; Song, C.P. Hydrogen peroxide is involved in abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, O.W. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal Biochem. 1980, 106, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chance, B.; Maehly, A.C. [136] Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 1955, 2, 764–775. [Google Scholar]

- Aebi, H. [13] Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 105, pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, A.S.; Beck, S.; Farinha, C.M.; Clarke, L.A.; Heda, G.D.; Steiner, B.; Sanz, J.; Gallati, S.; Amaral, M.D.; Harris, A.; et al. Methods for RNA extraction, cDNA preparation and analysis of CFTR transcripts. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2004, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.; Yigit, E.; Karaca, M.; Rodriguez, D.; Langhorst, B.; Shtatland, T.; Munafo, D.; Liu, P.; Apone, L.; Panchapakesa, V.; et al. Low-input transcript profiling with enhanced sensitivity using a highly efficient, low-bias and strand-specific RNA-Seq library preparation method. Cancer Res. 2017, 77 (Suppl. S13), 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, X.; Liu, Q.; Qin, L.; Jia, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Dai, X.; Yu, W.; Lei, X.; Wang, N.; et al. Transcriptomic Analysis of Rice (Jijing129) Reveals Growth and Gene Expression Responses to Different Red-Blue Laser Light Treatments. Plants 2025, 14, 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243712

Liang X, Liu Q, Qin L, Jia P, Wang J, Zhang C, Dai X, Yu W, Lei X, Wang N, et al. Transcriptomic Analysis of Rice (Jijing129) Reveals Growth and Gene Expression Responses to Different Red-Blue Laser Light Treatments. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243712

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Xuemei, Qi Liu, Li Qin, Peng Jia, Jianfeng Wang, Changjiang Zhang, Xintong Dai, Wenbo Yu, Xiaoyu Lei, Ningning Wang, and et al. 2025. "Transcriptomic Analysis of Rice (Jijing129) Reveals Growth and Gene Expression Responses to Different Red-Blue Laser Light Treatments" Plants 14, no. 24: 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243712

APA StyleLiang, X., Liu, Q., Qin, L., Jia, P., Wang, J., Zhang, C., Dai, X., Yu, W., Lei, X., Wang, N., & Yang, M. (2025). Transcriptomic Analysis of Rice (Jijing129) Reveals Growth and Gene Expression Responses to Different Red-Blue Laser Light Treatments. Plants, 14(24), 3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243712