Uncovering the Role of the KANADI Transcription Factor ZmKAN1 in Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

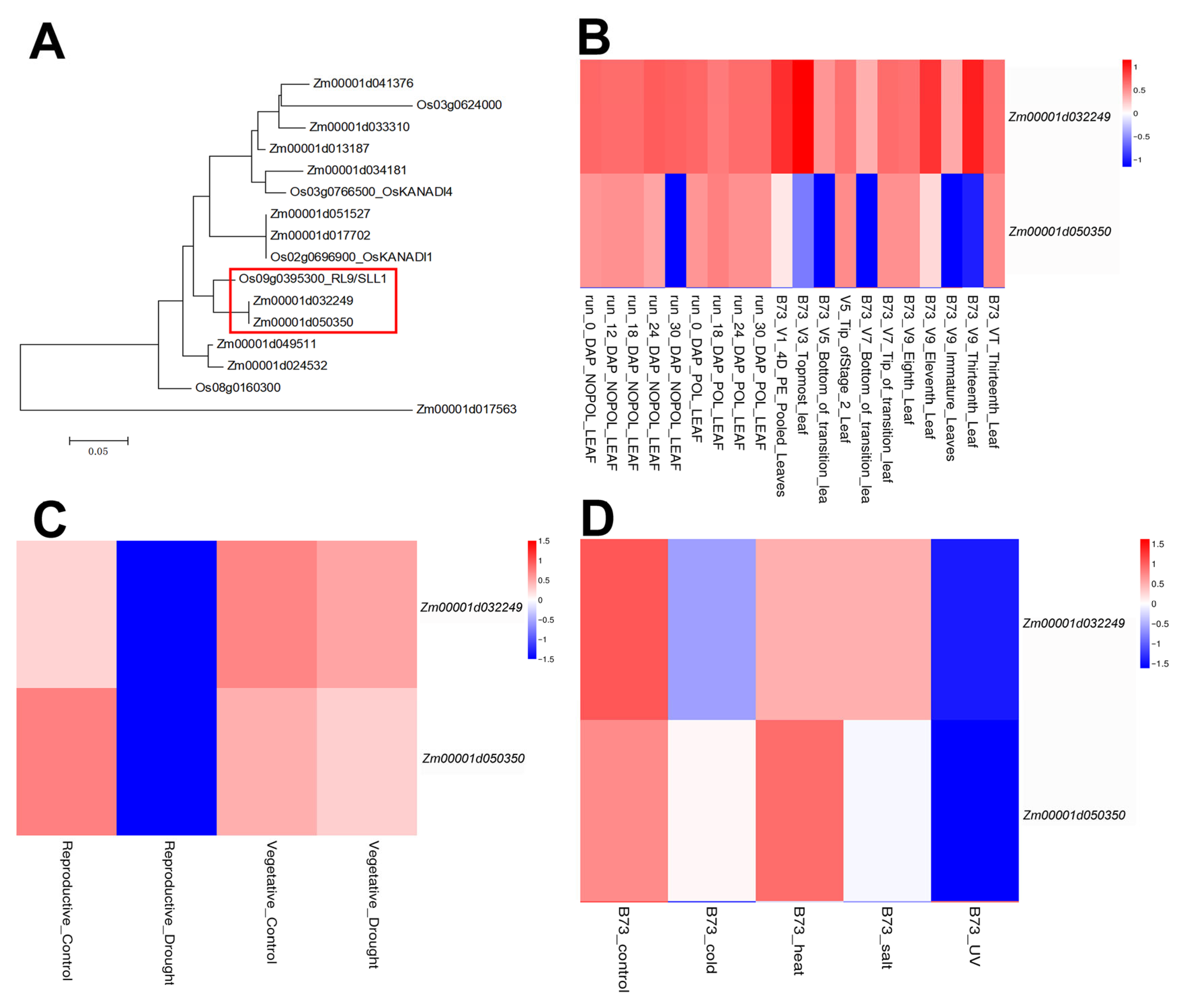

2.1. Identification of Maize KANADI Family Genes

2.2. The ZmKAN1 Mutant Exhibits Enhanced Drought Tolerance

2.3. Analysis of ZmKAN1 Expression Levels

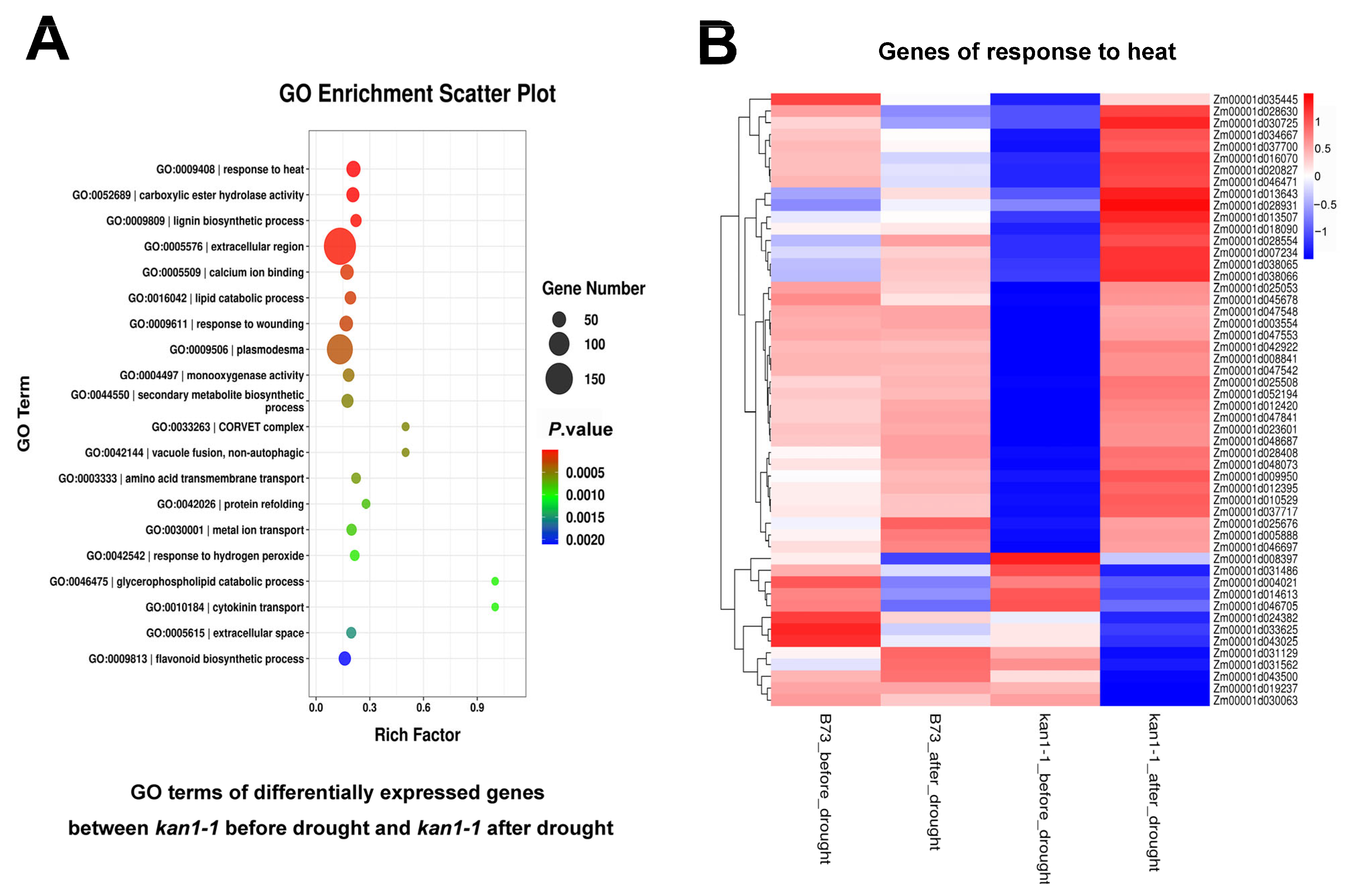

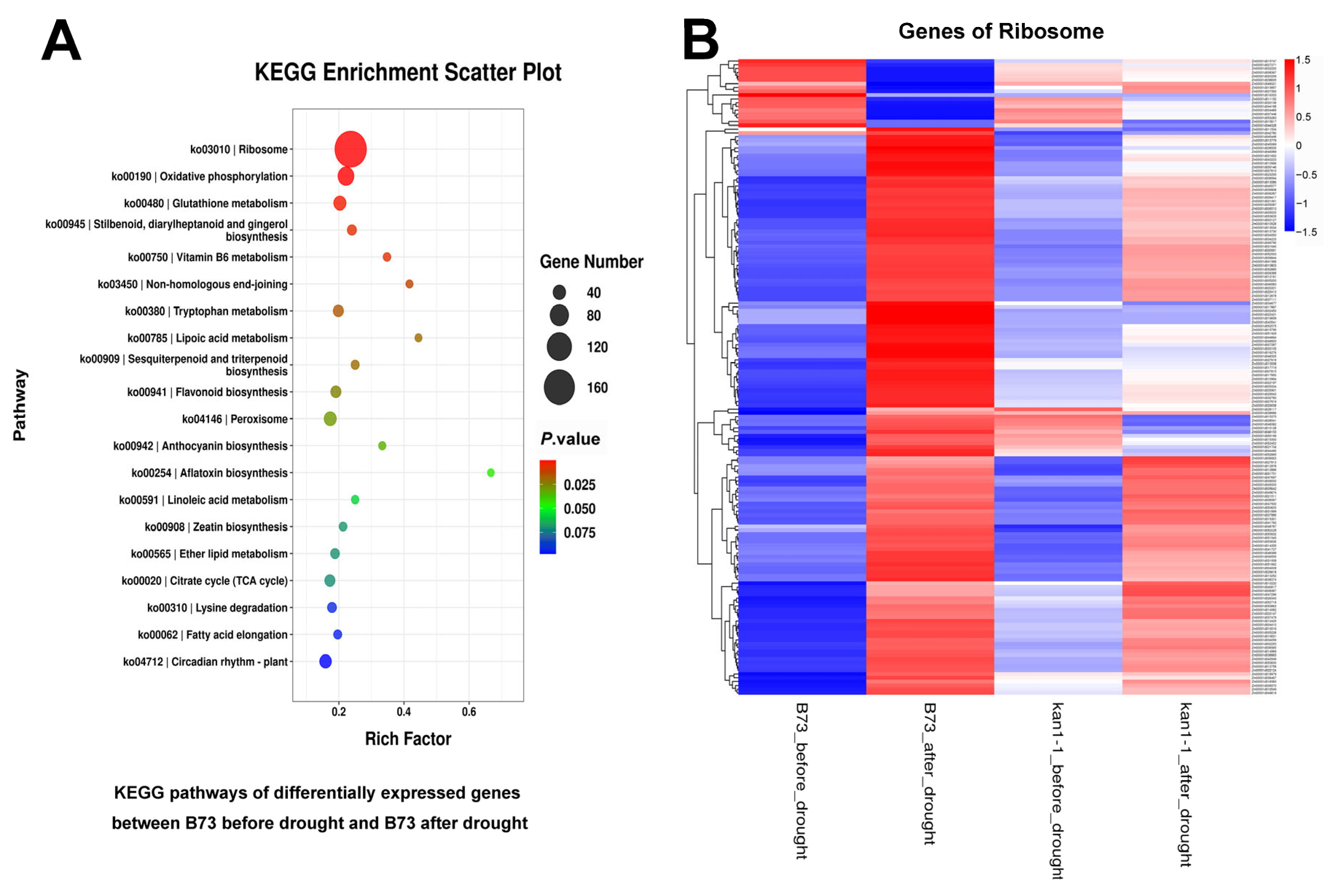

2.4. Transcriptome Profiling

3. Discussion

3.1. ZmKAN1 Modulates Drought Tolerance in Maize at the Seedling Stage

3.2. ZmKAN1 Potentiates Drought Tolerance Likely via Modulating Heat Response and Plant Hormone Pathways

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Identification of KANADI Family Genes in Maize

4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Gene Expression Patterns Analysis

4.4. Drought Tolerance Analysis of Wild-Type and Mutant Plants

4.5. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Analysis

4.6. Transcriptome Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, R.; Xie, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y. Identification of morphogenesis-related NDR kinase signaling network and its regulation on cold tolerance in maize. Plants 2023, 12, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Tian, R.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. DEK219 and HSF17 collaboratively regulate the kernel length in maize. Plants 2024, 13, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deinlein, U.; Stephan, A.B.; Horie, T.; Luo, W.; Xu, G.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, M.T.; Kui, J.S.; Thomas, J.; Heller, B.A.; Timmermans, M.C.P. microRNA-mediated repression of rolled leaf1 specifies maize leaf polarity. Nature 2004, 428, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, A.; Laufs, P. Co-ordination of developmental processes by small RNAs during leaf development. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, D. Advancements in rice leaf development research. Plants 2024, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Srivastava, A.K.; Pan, Y.; Bai, J.; Fang, J.; Shi, H.; Zhu, J.K. Knock-down of rice microRNA166 confers drought resistance by causing leaf rolling and altering stem xylem development. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2082–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.E. Shoot meristem function and leaf polarity: The role of class III HD-ZIP genes. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, R.A.; Bollman, K.; Taylor, R.A.; Bomblies, K.; Poethig, R.S. KANADI regulates organ polarity in Arabidopsis. Nature 2001, 411, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahle, M.I.; Kuehlich, J.; Staron, L.; von Arnim, A.G.; Golz, J.F. YABBYs and the transcriptional corepressors LEUNIG and LEUNIG_HOMOLOG maintain leaf polarity and meristem activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3105–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Lin, W.; Huang, T.; Poethig, R.S.; Springer, P.S.; Kerstetter, R.A. KANADI1 regulates adaxial-abaxial polarity in Arabidopsis by directly repressing the transcription of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 16392–16397. [Google Scholar]

- Yifhar, T.; Pekker, I.; Peled, D.; Friedlander, G.; Pistunov, A.; Sabban, M.; Wachsman, G.; Alvarez, J.P.; Amsellem, Z.; Eshed, Y. Failure of the tomato trans-acting short interfering RNA program to regulate AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 and ARF4 underlies the wiry leaf syndrome. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3575–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, M.W.; Reinhart, B.J.; Lim, L.P.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, B.; Bartel, D.P. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell 2002, 110, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skopelitis, D.S.; Benkovics, A.H.; Husbands, A.Y.; Timmermans, M.C.P. Boundary formation through a direct threshold-based readout of mobile small RNA gradients. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.; Hake, S. How a leaf gets its shape. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallory, A.C.; Vaucheret, H. Functions of microRNAs and related small RNAs in plants. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, S31–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Guan, C.; Wang, J.; Sajjad, M.; Ma, L.; Jiao, Y. Dynamic patterns of gene expression during leaf initiation. J. Genet. Genom. 2017, 44, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.H.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, X.D.; Qian, Q.; Xue, H.W. SHALLOT-LIKE1 is a KANADI transcription factor that modulates rice leaf rolling by regulating leaf abaxial cell development. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yan, C.J.; Zeng, X.H.; Yang, Y.C.; Fang, Y.W.; Tian, C.Y.; Sun, Y.W.; Cheng, Z.K.; Gu, M.H. ROLLED LEAF 9, encoding a GARP protein, regulates the leaf abaxial cell fate in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 68, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, J.F.; Floyd, S.K.; Alvarez, J.; Eshed, Y.; Hawker, N.P.; Izhaki, A.; Baum, S.F.; Bowman, J.L. Radial patterning of Arabidopsis shoots by Class III HD-ZIP and KANADI genes. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshed, Y.; Baum, S.F.; Perea, J.V.; Bowman, J.L. Establishment of polarity in lateral organs of plants. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Qin, F.; Jiang, C.; Yang, S. Genetic and molecular exploration of maize environmental stress resilience: Toward sustainable agriculture. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1496–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agurla, S.; Gahir, S.; Munemasa, S.; Murata, Y.; Raghavendra, A.S. Mechanism of stomatal closure in plants exposed to drought and cold stress. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1081, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uno, Y.; Furihata, T.; Abe, H.; Yoshida, R.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factors involved in an abscisic acid-dependent signal transduction pathway under drought and high-salinity conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11632–11637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, D.; Scherzer, S.; Mumm, P.; Stange, A.; Marten, I.; Bauer, H.; Ache, P.; Matschi, S.; Liese, A.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; et al. Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought-stress signaling kinase-phosphatase pair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21425–21430. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Z. Phosphorylation of ZmAL14 by ZmSnRK2.2 regulates drought resistance through derepressing ZmROP8 expression. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1334–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Sun, Z.; Feng, Z.; Qi, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Qi, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, S.; Gong, Z. ZmCIPK33 and ZmSnRK2.10 mutually reinforce the abscisic acid signaling pathway for combating drought stress in maize. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1787–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Seeve, C.M.; Cho, I.J.; Hearne, L.B.; Srivastava, G.P.; Joshi, T.; Smith, D.O.; Sharp, R.E.; Oliver, M.J. Water-deficit-induced changes in transcription factor expression in maize seedlings. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, P.F.; Zhao, J. Transcription factors as molecular switches to regulate drought adaptation in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Tang, X.; Liu, T.; Feng, X.; Wu, F.; Li, M.; Xie, W.; et al. A natural antisense transcript acts as a negative regulator for the maize drought stress response gene ZmNAC48. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2790–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Sun, X.; Bian, X.; Wei, T.; Han, T.; Yan, J.; Zhang, A. The transcription factor ZmNAC49 reduces stomatal density and improves drought tolerance in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Li, J.; Phan Tran, L.S.; Qin, F. A transposable element in a NAC gene is associated with drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, B.J.; Liu, T.; Newell, N.R.; Magnani, E.; Huang, T.; Kerstetter, R.; Michaels, S.; Barton, M.K. Establishing a framework for the ad/abaxial regulatory network of Arabidopsis: Ascertaining targets of Class III HOMEODOMAIN LEUCINE ZIPPER and KANADI Regulation. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3228–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Qu, C.; Liu, G. Genome-wide analysis of the KANADI gene family and its expression patterns under different nitrogen concentrations treatments in Populus trichocarpa. Phyton-Int. J Exp. Bot. 2023, 92, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, A.; Alqudah, A.M.; Dawood, M.F.A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Börner, A. Drought stress tolerance in wheat and barley: Advances in physiology, breeding and genetics research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, L.A.; Bhat, M.Y.; Lone, A.A.; Dar, Z.A.; Mir, B.A. Genetic, molecular and physiological crosstalk during drought tolerance in maize (Zea mays): Pathways to resilient agriculture. Planta 2024, 260, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Wang, Y.; Qu, J.; Miao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Guan, S.; Ma, Y. The overexpression of ascorbate peroxidase 2 (APX2) gene improves drought tolerance in maize. Mol. Breed. 2025, 45, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Li, H.Y.; Song, Y.L.; Zhang, P.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bu, H.H.; Dong, C.L.; Ren, Z.Q.; Chang, J.Z. Genome-wide association study for plant height and ear height in maize under well-watered and water-stressed conditions. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, Y.; Zenda, T.; Liu, S.; Dong, A.; Kou, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, N.; Duan, H. CHH demethylation in the ZmGST2 promoter enhances maize drought tolerance by regulating ROS scavenging and root growth. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, F.; Mu, C.; Ma, C.; Yao, G.; Sun, Y.; Hou, J.; Leng, B.; Liu, X. The ZmbHLH47-ZmSnRK2.9 module promotes drought tolerance in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, O.K.; Macherel, D. The crucial role of plant mitochondria in orchestrating drought tolerance. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vanlerberghe, G.C. A lack of mitochondrial alternative oxidase compromises capacity to recover from severe drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 149, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Feng, C.; Zheng, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, F.; Shan, D.; Liu, X.; Kong, J. Plant mitochondria synthesize melatonin and enhance the tolerance of plants to drought stress. J. Pineal Res. 2017, 63, e12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Hu, X. Quantitative proteomic analyses identify ABA-related proteins and signal pathways in maize leaves under drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzelou, S.; Kamath, K.S.; Masoomi-Aladizgeh, F.; Johnsen, M.M.; Atwell, B.J.; Haynes, P.A. Wild and cultivated species of rice have distinctive proteomic responses to drought. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Chai, Q.; Liu, C.; Niu, X.; Li, W.; Shang, X.; Gu, A.; Zhang, D.; Guo, W. Cotton GhNAC4 promotes drought tolerance by regulating secondary cell wall biosynthesis and ribosomal protein homeostasis. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1052–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Liu, J.; Ren, W.; Yang, Q.; Chai, Z.; Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Lang, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. Gene-indexed mutations in maize. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.D.; Tian, R.; Zhang, J.J.; Liu, H.M.; Li, Y.P.; Hu, Y.F.; Yu, G.W.; Huang, Y.B.; Liu, Y.H. Dek219 encodes the DICER-LIKE1 protein that affects chromatin accessibility and kernel development in maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2961–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 2012, 6, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, S.; Tian, R. Uncovering the Role of the KANADI Transcription Factor ZmKAN1 in Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Maize. Plants 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010002

Xie S, Tian R. Uncovering the Role of the KANADI Transcription Factor ZmKAN1 in Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Maize. Plants. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Sidi, and Ran Tian. 2026. "Uncovering the Role of the KANADI Transcription Factor ZmKAN1 in Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Maize" Plants 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010002

APA StyleXie, S., & Tian, R. (2026). Uncovering the Role of the KANADI Transcription Factor ZmKAN1 in Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Maize. Plants, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010002