Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis Regulates Pistil Development and Pollination in Salix linearistipularis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

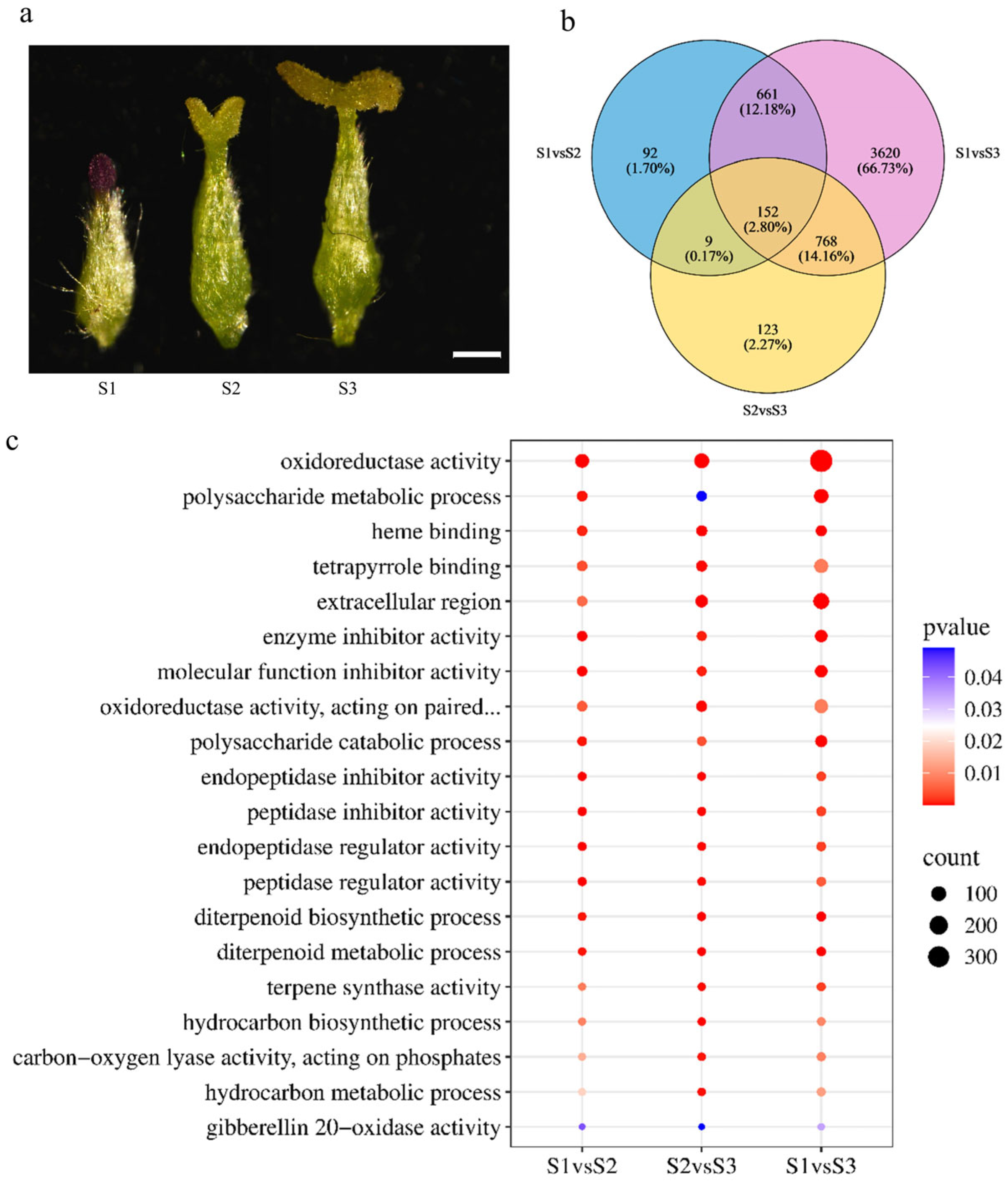

2.1. Morphological Observation and RNA-Seq Revealed Distinct Pistil Developmental Stages in S. linearistipularis

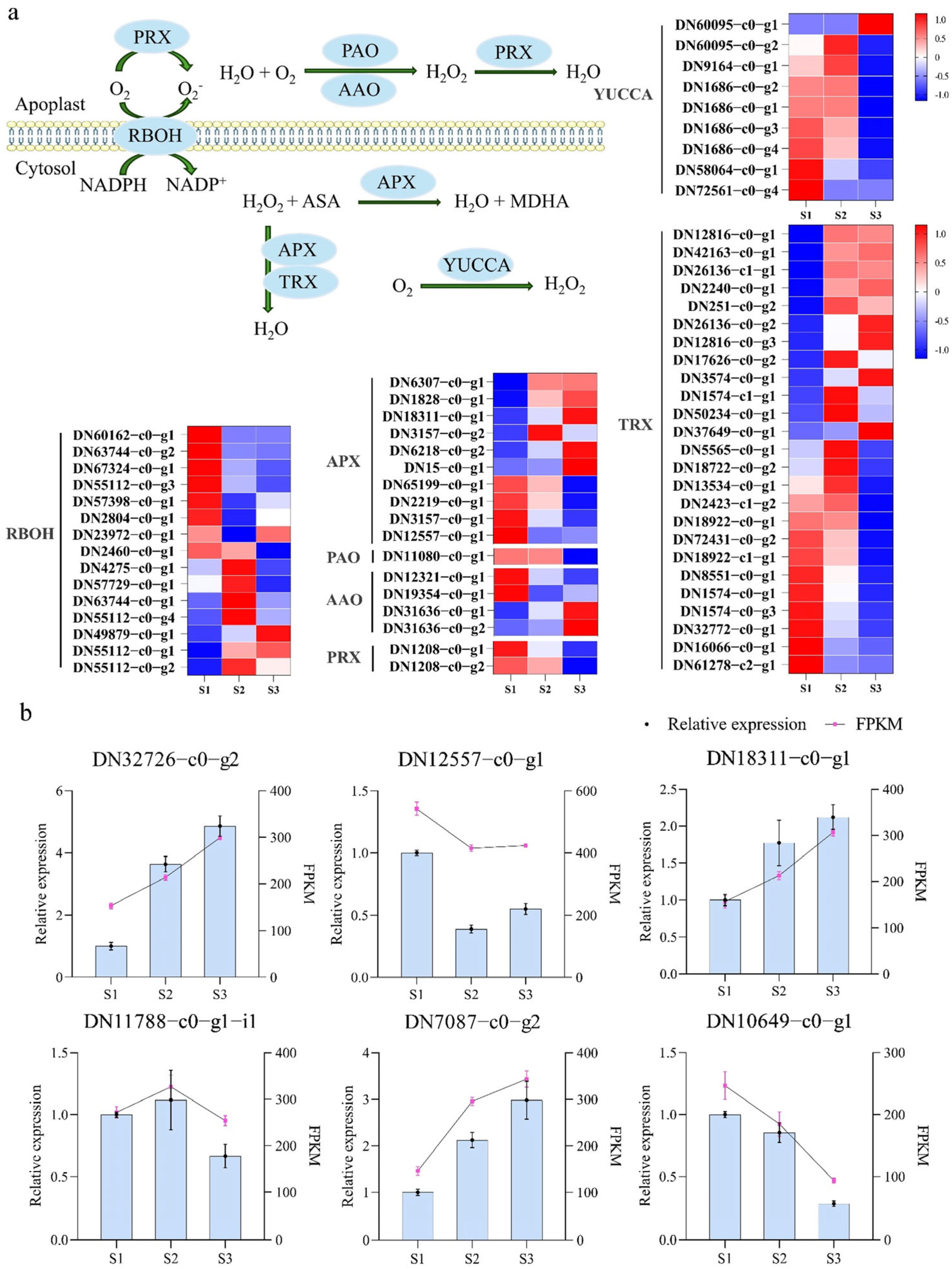

2.2. The ROS-Related Genes Are Differentially Expressed During Pistil Development in S. linearistipularis

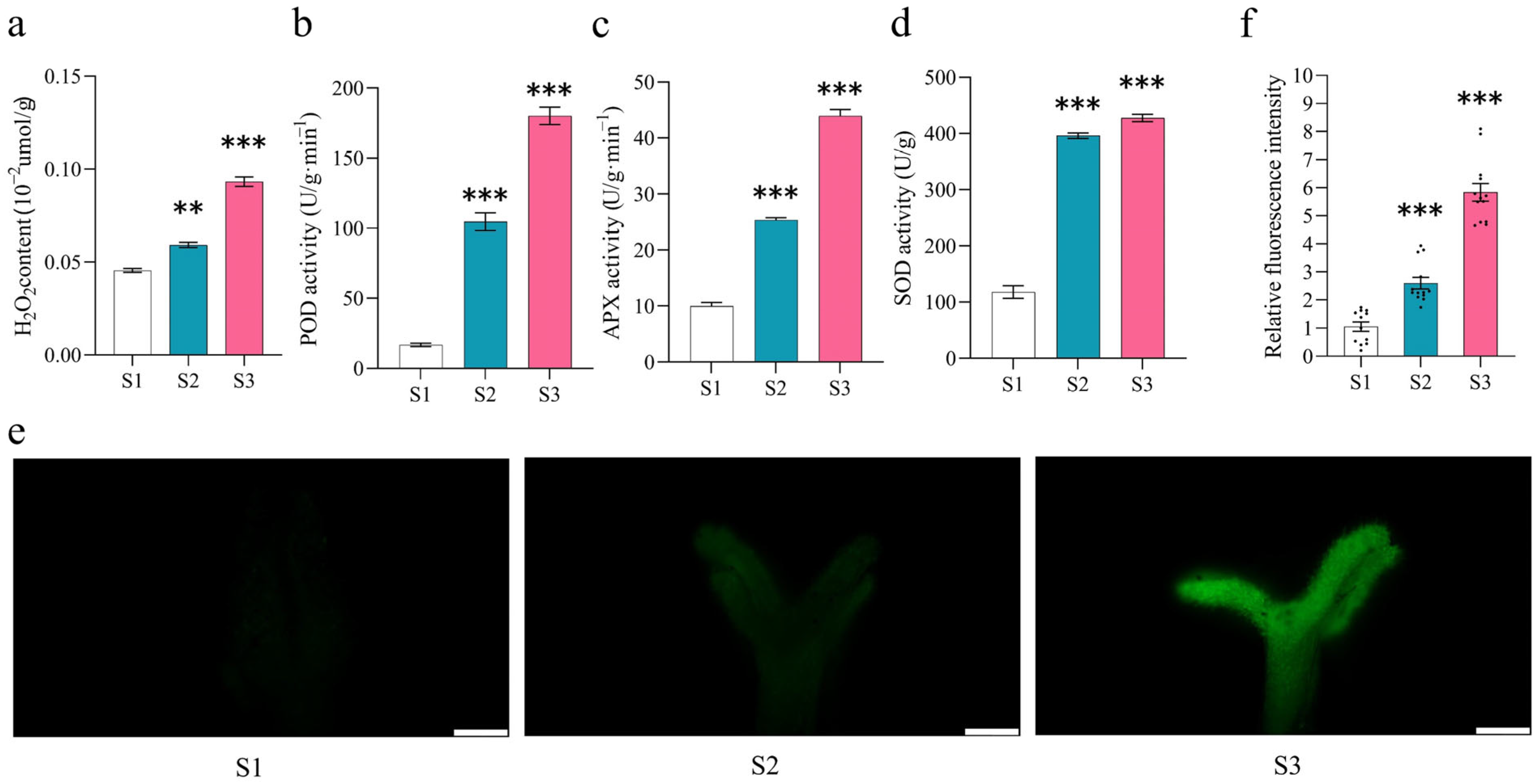

2.3. ROS Scavenging Activity Increased During Pistil Development in S. linearistipularis

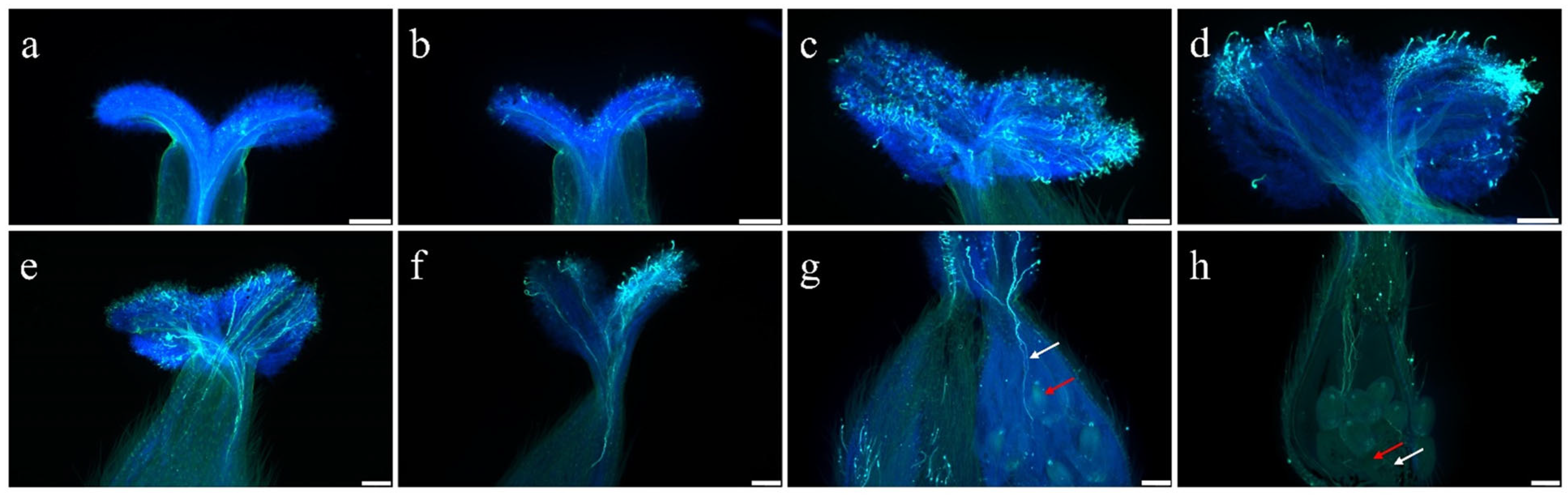

2.4. ROS Levels Decrease After Pollination and Enhances Pollen Tube Growth in Pistils of S. linearistipularis

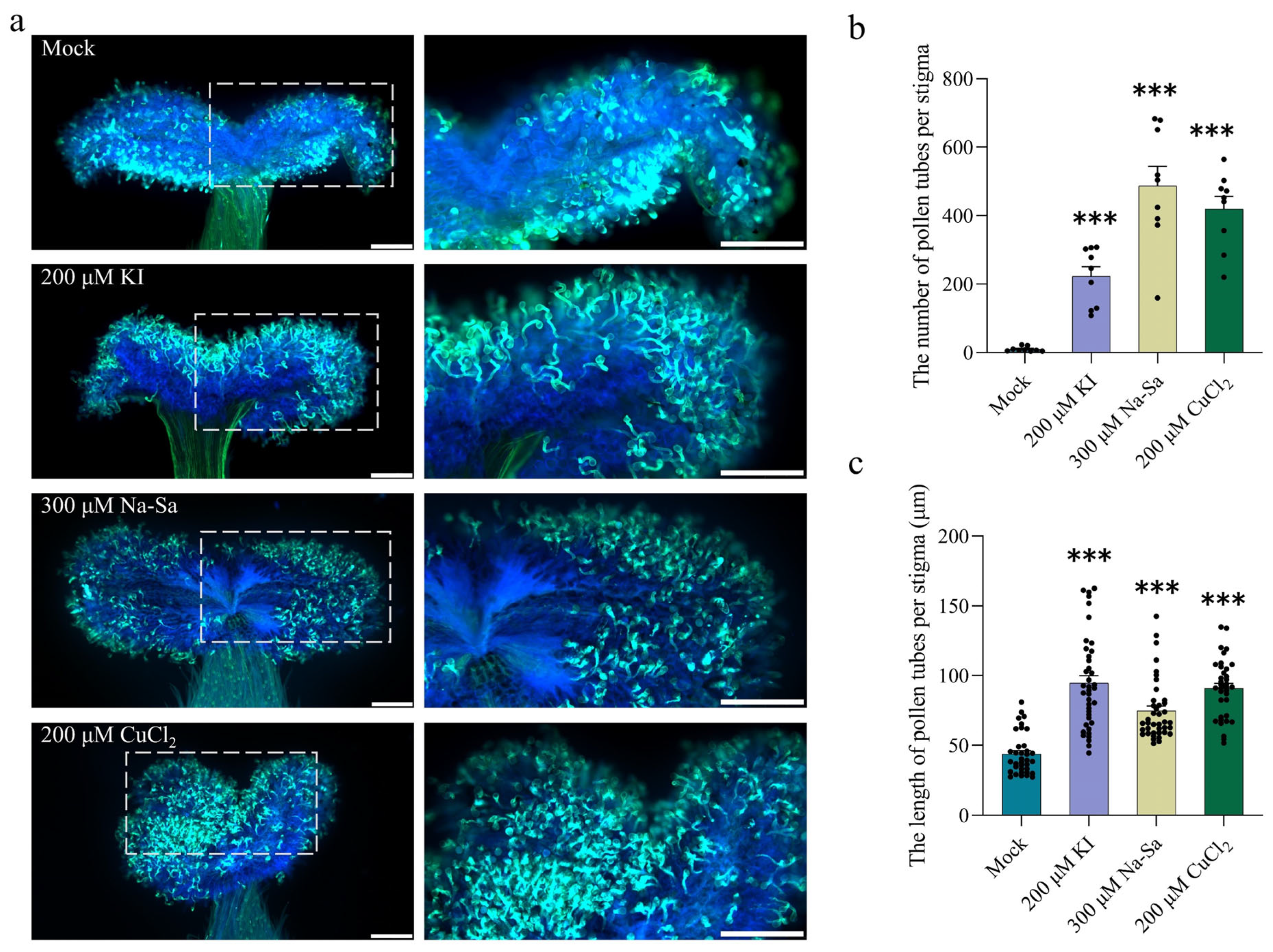

2.5. Increase in Stigmatic ROS Inhibits Pollen Tube Germination and Elongation

2.6. Reduced ROS Levels Promote Pollen Tube Growth

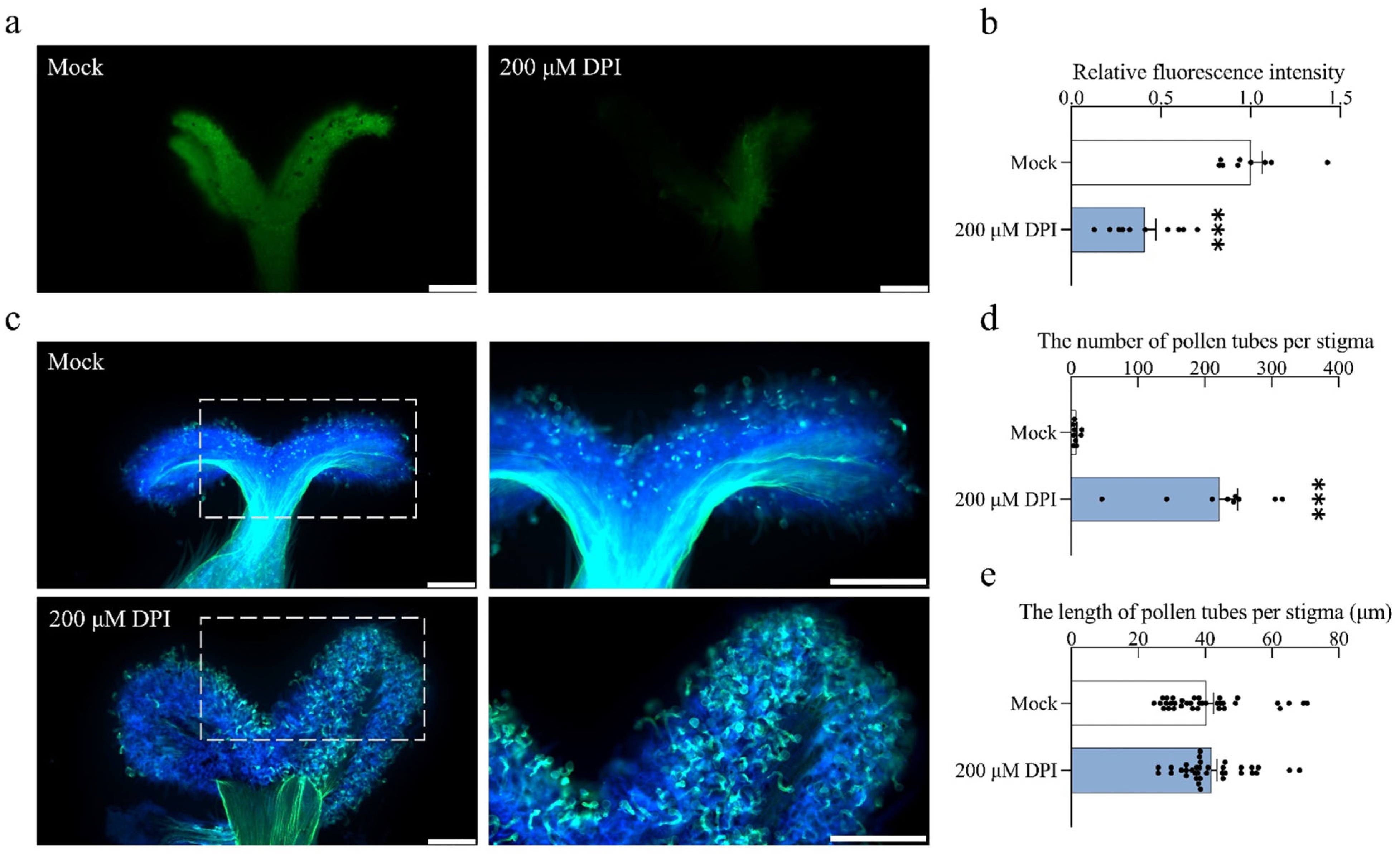

2.7. Inhibition of RBOH-Mediated ROS Production Promotes Pollen Tube Germination

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Experimental Materials and Transcriptome Sequencing

4.2. Physiological Parameter Measurement

4.3. Detection of ROS in the Pistil

4.4. In Vitro Culture Experiment of Pistil

4.5. Fluorescence Microscopy Observation

4.6. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lan, X.; Yang, J.; Abhinandan, K.; Nie, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Samuel, M.A. Flavonoids and ROS Play Opposing Roles in Mediating Pollination in Ornamental Kale (Brassica oleracea Var. acephala). Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linskens, H.F.; Linskens, H.F. Developmental Biology of Reproduction: Current Problems. Phytomorphology 1981, 31, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.-Q.; Liu, C.Z.; Li, D.D.; Zhao, T.T.; Li, F.; Jia, X.N.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Zhang, X.S. The Arabidopsis KINβγ Subunit of the SnRK1 Complex Regulates Pollen Hydration on the Stigma by Mediating the Level of Reactive Oxygen Species in Pollen. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.V.; Fiol, D.F.; Sundaresan, V.; Zabaleta, E.J.; Pagnussat, G.C. Oiwa, a Female Gametophytic Mutant Impaired in a Mitochondrial Manganese-Superoxide Dismutase, Reveals Crucial Roles for Reactive Oxygen Species during Embryo Sac Development and Fertilization in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaranarayanan, S.; Ju, Y.; Kessler, S.A. Reactive Oxygen Species as Mediators of Gametophyte Development and Double Fertilization in Flowering Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, S.; Jakada, B.H.; Qin, H.; Zhan, Y.; Lan, X. Transcriptomics Reveal the Involvement of Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Sequestration during Stigma Development and Pollination in Fraxinus Mandshurica. For. Res. 2024, 4, e014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Nakajima, R.; Iwano, M.; Kanaoka, M.M.; Kimura, S.; Takeda, S.; Kawarazaki, T.; Senzaki, E.; Hamamura, Y.; Higashiyama, T.; et al. Ca2+-Activated Reactive Oxygen Species Production by Arabidopsis RbohH and RbohJ Is Essential for Proper Pollen Tube Tip Growth. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potocký, M.; Jones, M.A.; Bezvoda, R.; Smirnoff, N.; Žárský, V. Reactive Oxygen Species Produced by NADPH Oxidase Are Involved in Pollen Tube Growth. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Kita, D.; Johnson, E.A.; Aggarwal, M.; Gates, L.; Wu, H.-M.; Cheung, A.Y. Reactive Oxygen Species Mediate Pollen Tube Rupture to Release Sperm for Fertilization in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Autréaux, B.; Toledano, M.B. ROS as Signalling Molecules: Mechanisms That Generate Specificity in ROS Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellosillo, T.; Vicente, J.; Kulasekaran, S.; Hamberg, M.; Castresana, C. Emerging Complexity in Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Signaling during the Response of Plants to Pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species: Generation, Signaling, and Defense Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, F.; Fariduddin, Q.; Khan, T.A. Hydrogen Peroxide as a Signalling Molecule in Plants and Its Crosstalk with Other Plant Growth Regulators under Heavy Metal Stress. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Suzuki, N.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis and Signalling during Drought and Salinity Stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafakheri, A.; Siosemardeh, A.; Bahramnejad, B.; Struik, P.C.; Sohrabi, Y. Effect of Drought Stress on Yield, Proline and Chlorophyll Contents in Three Chickpea Cultivars. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2010, 4, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandalios, J.G. Oxidative Stress: Molecular Perception and Transduction of Signals Triggering Antioxidant Gene Defenses. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Medicas E Biol. 2005, 38, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszczak, C.; Carmody, M.; Kangasjärvi, J. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, S. Genome-wide identification and analysis of class III peroxidases in Betula pendula. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrot, N.; Rouhier, N.; Gelhaye, E.; Jacquot, J.-P. Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Antioxidant Systems in Plant Mitochondria. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 129, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. ROS Are Good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Branicky, R.; Noë, A.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide Dismutases: Dual Roles in Controlling ROS Damage and Regulating ROS Signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Guan, X.; Song, J.; Ma, S. Biochemical and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Key Salinity and Alkalinity Stress Response and Tolerance Pathways in Salix Linearistipularis Inoculated with Trichoderma. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Sun, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X.; Ma, S.; Qiao, K.; Zhou, A.; Bu, Y.; Liu, S. Sexual Differences in Physiological and Transcriptional Responses to Salinity Stress of Salix Linearistipularis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 517962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.A.; Nara, K.; Ma, S.; Takano, T.; Liu, S. Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Community in Alkaline-Saline Soil in Northeastern China. Mycorrhiza 2009, 19, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Guan, X.; Cui, H.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, S. The Impact of Salt-Tolerant Plants on Soil Nutrients and Microbial Communities in Soda Saline-Alkali Lands of the Songnen Plain. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1592834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Sha, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Na2CO3-Responsive Mechanism Insight from Quantitative Proteomics and SlRUB Gene Function in Salix Linearistipularis Seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Fu, W.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Bu, Y. Differential Salt Stress Resistance in Male and Female Salix Linearistipularis Plants: Insights from Transcriptome Profiling and the Identification of the 4-Hydroxy-Tetrahydrodipicolinate Synthase Gene. Planta 2024, 260, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Leydon, A.R.; Manziello, A.; Pandey, R.; Mount, D.; Denic, S.; Vasic, B.; Johnson, M.A.; Palanivelu, R. Penetration of the Stigma and Style Elicits a Novel Transcriptome in Pollen Tubes, Pointing to Genes Critical for Growth in a Pistil. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Qu, H. RNA-Seq Analysis of Compatible and Incompatible Styles of Pyrus Species at the Beginning of Pollination. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 102, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, H.; Han, R.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, S. BpAP1 directly regulates BpDEF to promote male inflorescence formation in Betula platyphylla× B. pendula. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Machinery in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Species Signalling in Plant Stress Responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; He, F.; Ning, Y.; Wang, G.-L. Fine-Tuning of RBOH-Mediated ROS Signaling in Plant Immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Tang, C.; Lv, S.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, P. PbRbohH/J Mediates ROS Generation to Regulate the Growth of Pollen Tube in Pear. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 2024, 207, 108342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, P.; Hong, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, R.; Liang, Y. The Receptor-like Cytosolic Kinase RIPK Activates NADP-Malic Enzyme 2 to Generate NADPH for Fueling ROS Production. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Hunter, K.; Vaahtera, L.; Tran, H.C.; Citterico, M.; Vaattovaara, A.; Rokka, A.; Stolze, S.C.; Harzen, A.; Meißner, L.; et al. CRK2 and C-Terminal Phosphorylation of NADPH Oxidase RBOHD Regulate Reactive Oxygen Species Production in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1063–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Fartyal, D.; Agarwal, A.; Shukla, T.; James, D.; Kaul, T.; Negi, Y.K.; Arora, S.; Reddy, M.K. Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants: Myriad Roles of Ascorbate Peroxidase. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, I.; Tripathi, B.N. Plant Peroxiredoxins: Catalytic Mechanisms, Functional Significance and Future Perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Bhargava, P.; Rai, L.C. Salinity and Copper-Induced Oxidative Damage and Changes in the Antioxidative Defence Systems of Anabaena Doliolum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. A Re-Evaluation of the ATP: NADPH Budget during C3 Photosynthesis: A Contribution from Nitrate Assimilation and Its Associated Respiratory Activity? J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 1895–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Lai, Q.Q.T.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Yan, H.; Zhao, Q.; Bao, H.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals regulatory processes of transcription factors on anthocyanin accumulation in the bark of Populus simonii× P. nigra. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2025, 163, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Y.; Yu, S.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Yin, H. The Flavonoid Biosynthesis Network in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid Biosynthesis. A Colorful Model for Genetics, Biochemistry, Cell Biology, and Biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, I.; Alegre, L.; Van Breusegem, F.; Munné-Bosch, S. How Relevant Are Flavonoids as Antioxidants in Plants? Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourcel, L.; Routaboul, J.-M.; Cheynier, V.; Lepiniec, L.; Debeaujon, I. Flavonoid Oxidation in Plants: From Biochemical Properties to Physiological Functions. Trends Plant Sci. 2007, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlemann, J.K.; Younts, T.L.B.; Muday, G.K. Flavonols Control Pollen Tube Growth and Integrity by Regulating ROS Homeostasis during High-Temperature Stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11188–E11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A.; Zhang, X.; Busatto, N. Editorial: Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1230664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohge, T.; Watanabe, M.; Hoefgen, R.; Fernie, A.R. The Evolution of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in the Green Lineage. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 48, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, N.-Q.; Lin, H.-X. Contribution of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism to Plant Development and Plant-Environment Interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Signaling, and Scavenging During Abiotic Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D.; Harish; Singh, R.K.; Verma, K.K.; Sharma, L.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Meena, M.; Gour, V.S.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; et al. Recent Developments in Enzymatic Antioxidant Defence Mechanism in Plants with Special Reference to Abiotic Stress. Biology 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irato, P.; Santovito, G. Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Molecules with Antioxidant Function. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanović, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Natić, M.; Kuča, K.; Jaćević, V. The Significance of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: A Concise Overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 552969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breygina, M.; Schekaleva, O.; Klimenko, E.; Luneva, O. The Balance between Different ROS on Tobacco Stigma during Flowering and Its Role in Pollen Germination. Plants 2022, 11, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podobedova, A.; Baranova, E.N.; Gulevich, A.A.; Chaban, I.A.; Breygina, M. Comprehensive Study of Sexual Reproduction in Nicotiana Tabacum Plants Overexpressing H2O2-Producing Enzymes: Superoxide Dismutase and Choline Oxidase. Plants 2025, 14, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.-C.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.-Y.; Song, C.-P. Reactive Oxygen Species: Multidimensional Regulators of Plant Adaptation to Abiotic Stress and Development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, F.; Li, J.; Ai, Y.; Shangguan, K.; Li, P.; Lin, F.; Liang, Y. DGK5β-Derived Phosphatidic Acid Regulates ROS Production in Plant Immunity by Stabilizing NADPH Oxidase. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 425–440.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Fan, M.; Qin, Z.; Lv, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, N.; Li, X.; Han, C.; et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Positively Regulates Brassinosteroid Signaling through Oxidation of the BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 Transcription Factor. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, S.M.; Desikan, R.; Hancock, J.T.; Hiscock, S.J. Production of Reactive Oxygen Species and Reactive Nitrogen Species by Angiosperm Stigmas and Pollen: Potential Signalling Crosstalk? New Phytol. 2006, 172, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guan, X.; Zhao, C.; Song, J.; Shi, J.; Jakada, B.H.; Dou, G.; Lan, X.; Ma, S. Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis Regulates Pistil Development and Pollination in Salix linearistipularis. Plants 2026, 15, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010168

Guan X, Zhao C, Song J, Shi J, Jakada BH, Dou G, Lan X, Ma S. Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis Regulates Pistil Development and Pollination in Salix linearistipularis. Plants. 2026; 15(1):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010168

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Xueting, Chaoning Zhao, Junjie Song, Jiaqi Shi, Bello Hassan Jakada, Gege Dou, Xingguo Lan, and Shurong Ma. 2026. "Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis Regulates Pistil Development and Pollination in Salix linearistipularis" Plants 15, no. 1: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010168

APA StyleGuan, X., Zhao, C., Song, J., Shi, J., Jakada, B. H., Dou, G., Lan, X., & Ma, S. (2026). Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis Regulates Pistil Development and Pollination in Salix linearistipularis. Plants, 15(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010168