MeJA-Induced Plant Disease Resistance: A Review

Abstract

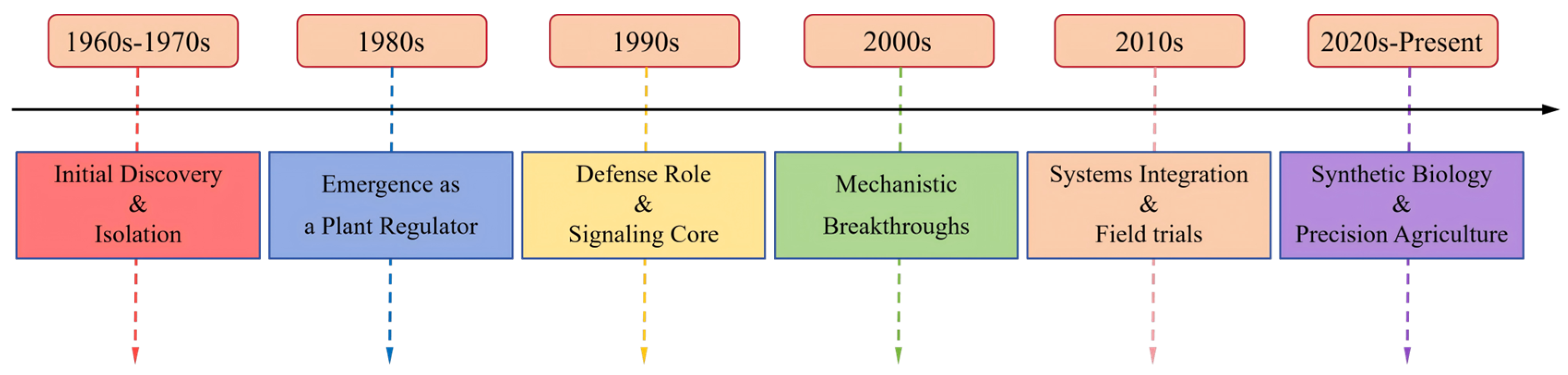

1. Introduction

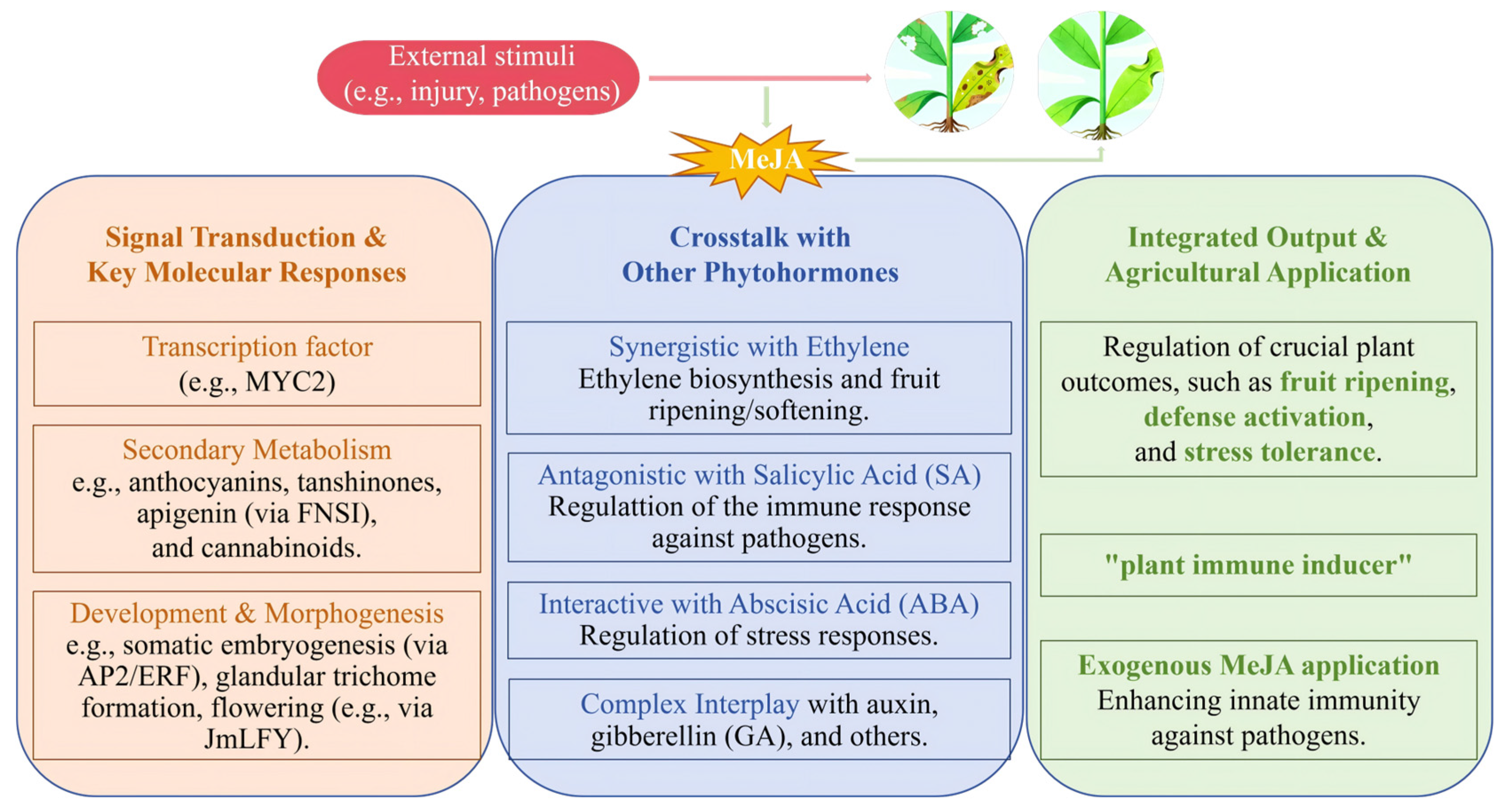

2. Mechanism of MeJA-Induced Disease Resistance

2.1. Direct Inhibitory Effect of MeJA on Plant Pathogens

2.2. MeJA-Induced Defense Responses in Different Plants

2.3. Monitoring the Effects of MeJA Treatment

3. Application Strategies of MeJA-Induced Plant Resistance

3.1. Fundamental Mechanisms of MeJA-Induced Effects

3.2. Combined Application of MeJA and Biological Control

3.3. Combination of MeJA with Other Control Pathways

4. Challenges in MeJA-Induced Resistance

4.1. Safety and Practical Application Considerations

4.2. Durability and Stability of MeJA-Induced Resistance

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MeJA | Methyl jasmonate |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| FNSI | Flavone synthase I |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| FIN219 | FAR-RED INSENSITIVE 219 |

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| FHB | Fusarium head blight |

| DON | deoxynivalenol |

| PKA | protein kinase A |

| BBTI | Bowman-Birk type protease inhibitor |

| Abm | monooxygenase |

| 12OH-JA | 12-hydroxy-JA |

| Z-3-HAC | Z-3-hexenyl acetate |

| PR1 | pathogenesis-related protein 1 |

| TRXM | thioredoxin M-type chloroplast precursor |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| MYMIV | Mungbean Yellow Mosaic India Virus |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| PAL5 | phenylalanine ammonia-lyase |

| BSMT | benzoic acid/salicylic acid carboxyl methyltransferase |

| ICS | isochorismate synthase |

| OA | oxalic acid |

| XEGs | xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanases |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| HLB | Huanglongbing |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| AtNPR1 | Arabidopsis thaliana NPR1 gene |

| ARF | auxin response factor |

| IAA | indole-3-acetic acid |

| BVOCs | biogenic volatile organic compounds |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| MeSA | methyl salicylate |

| CD | methyl-β-cyclodextrin |

| FON2 | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum race 2 |

| ClCOMT1 | caffeic acid O-methyltransferase 1 |

| CuPh | copper phosphite |

References

- Demole, E.; Lederer, E.; Mercier, D. Isolement et détermination de la structure du jasmonate de méthyle, constituant odorant caractéristique de l’essence de jasmin. Helv. Chim. Acta 1962, 45, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vick, B.A.; Zimmerman, D.C. Biosynthesis of jasmonic acid by several plant species. Plant Physiol. 1984, 75, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, E.E.; Ryan, C.A. Interplant communication: Airborne methyl jasmonate induces synthesis of proteinase inhibitors in plant leaves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 7713–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creelman, R.A.; Mullet, J.E. Biosynthesis and action of jasmonates in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1997, 48, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memelink, J. The use of genetics to dissect plant secondary pathways. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005, 8, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Hause, B. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 1021–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Calvo, P.; Chini, A.; Fernández-Barbero, G.; Chico, J.M.; Gimenez-Ibanez, S.; Geerinck, J.; Eeckhout, D.; Schweizer, F.; Godoy, M.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; et al. The Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factors MYC3 and MYC4 are targets of JAZ repressors and act additively with MYC2 in the activation of jasmonate responses. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazan, K.; Manners, J.M. MYC2: The master in action. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traw, M.B.; Bergelson, J. Interactive effects of jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and gibberellin on induction of trichomes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Sano, R.; Wada, T.; Takabayashi, J.; Okada, K. Jasmonic acid control of GLABRA3 links inducible defense and trichome patterning in Arabidopsis. Development 2009, 136, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Fits, L.; Memelink, J. ORCA3, a jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. Science 2000, 289, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, L.; Morreel, K.; De Witte, E.; Lammertyn, F.; Van Montagu, M.; Boerjan, W.; Inzé, D.; Goossens, A. Mapping methyl jasmonate-mediated transcriptional reprogramming of metabolism and cell cycle progression in cultured Arabidopsis cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; Kissen, R.; Bones, A.M. Phytoalexins in defense against pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, K. MYC: Orchestrating secondary metabolism and glandular trichome formation. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, J.J.; Choi, Y.D. Methyl jasmonate as a vital substance in plants. Trends Genet. 2003, 19, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, T.; Luo, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, P.; Zhang, G. MeJA and Post-Harvest Storage of Fruits and Vegetables and Metabolite Synthesis in Plants. Physiol. Plant 2025, 177, e70304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, M.; Wu, T.; Song, T.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, J. MdWER interacts with MdERF109 and MdJAZ2 to mediate methyl jasmonate- and light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple fruit. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, C.; Lyu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, Z.; Lin, Y. Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution, and expression analysis provide new insights into the APETALA2/ethylene responsive factor (AP2/ERF) superfamily in Dimocarpus longan Lour. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; He, L.; Xu, S.; Wan, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhu, W. Expression Analysis, Functional Marker Development and Verification of AgFNSI in Celery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, M.; Gu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Cai, S.; Guo, F.; et al. Deep learning-based quantification and transcriptomic profiling reveal a methyl jasmonate-mediated glandular trichome formation pathway in Cannabis sativa. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Kai, G. Methyl jasmonate induction of tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots is mediated by JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN repressor proteins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; He, Q.; Hu, Y.; Feng, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z. Integrated physiology, transcriptome and proteome analyses highlight the potential roles of multiple hormone-mediated signaling pathways involved in tapping panel dryness in rubber tree. Plant Sci. 2024, 341, 112011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jia, W.; Peng, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, R. Endogenous cAMP elevation in Brassica napus causes changes in phytohormone levels. Plant Signal. Behav. 2024, 19, 2310963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ji, Y.; Tan, D.; Yuan, H.; Wang, A. The Jasmonate-Activated Transcription Factor MdMYC2 Regulates ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR and Ethylene Biosynthetic Genes to Promote Ethylene Biosynthesis during Apple Fruit Ripening. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1316–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Chen, C.L.; Hsieh, H.L. Far-Red Light-Mediated Seedling Development in Arabidopsis Involves FAR-RED INSENSITIVE 219/JASMONATE RESISTANT 1-Dependent and -Independent Pathways. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chai, X.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tariq, A.; Li, X.; Zeng, F. Potential role of root-associated bacterial communities in adjustments of desert plant physiology to osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 204, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, J.; Dong, T.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J.; Liu, C. Promoter cloning and activities analysis of JmLFY, a key gene for flowering in Juglans mandshurica. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1243030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Grierson, D.; Yin, X. Methyl Jasmonate Enhances Ethylene Synthesis in Kiwifruit by Inducing NAC Genes That Activate ACS1. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 3267–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astle, M.C.; Rubery, P.H. Modulation of carrier-mediated uptake of abscisic acid by methyl jasmonate in Phaseolus coccineus L. Planta 1985, 166, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, Z.; Christensen, S.A.; Yan, Y.; He, Y.; Borrego, E.; Kolomiets, M.V. Green leaf volatiles and jasmonic acid enhance susceptibility to anthracnose diseases caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in maize. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Sun, Y.; Jin, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, M.; Song, X. Methyl jasmonate mitigates Fusarium graminearum infection in wheat by inhibiting deoxynivalenol synthesis. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Qin, S.; Cui, F.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, G. MeJA inhibits fungal growth and DON toxin production by interfering with the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway in the wheat scab fungus Fusarium graminearum. mBio 2025, 16, e03151-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zeng, W.; Wang, P.; Zheng, X.; Yang, F. A new Bowman-Birk type protease inhibitor regulated by MeJA pathway in maize exhibits anti-feedant activity against the Ostrinia furnacalis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 114, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukermans, J.; Inzé, A.; Mathys, J.; De Coninck, B.; van de Cotte, B.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Van Breusegem, F. ARACINs, Brassicaceae-Specific Peptides Exhibiting Antifungal Activities against Necrotrophic Pathogens in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, S.; Shi, L.; Lin, W.; Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Guan, D.; He, S. Over-Expression of Rice CBS Domain Containing Protein, OsCBSX3, Confers Rice Resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae Inoculation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 15903–15917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patkar, R.; Benke, P.; Qu, Z.; Constance Chen, Y.Y.; Yang, F.; Swarup, S.; Naqvi, N. A fungal monooxygenase-derived jasmonate attenuates host innate immunity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameye, M.; Audenaert, K.; De Zutter, N.; Steppe, K.; Van Meulebroek, L.; Vanhaecke, L.; De Vleesschauwer, D.; Haesaert, G.; Smagghe, G. Priming of Wheat with the Green Leaf Volatile Z-3-Hexenyl Acetate Enhances Defense against Fusarium graminearum But Boosts Deoxynivalenol Production. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1671–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, S.X.; Yin, G.H.; Yang, Z.Z.; Lee, S.; Liu, C.G.; Zhao, D.D.; Ma, Y.K.; Song, F.Q.; et al. Proteomics of methyl jasmonate induced defense response in maize leaves against Asian corn borer. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Yan, Q.; Gan, S.; Xue, D.; Wang, H.; Xing, H.; Zhao, J.; Guo, N. GmWRKY40, a member of the WRKY transcription factor genes identified from Glycine max L.; enhanced the resistance to Phytophthora sojae. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, N.; Basak, J. Exogenous application of methyl jasmonate induces defense response and develops tolerance against mungbean yellow mosaic India virus in Vigna mungo. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 46, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J.; Chan, Y.-L.; Shien, C.H.; Yeh, K.-W. Molecular characterization of fruit-specific class III peroxidase genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 177, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, P.; Igielski, R.; Pollmann, S.; Kępczyńska, E. Priming of seeds with methyl jasmonate induced resistance to hemi-biotroph Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici in tomato via 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid, salicylic acid, and flavonol accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 179, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-Y.; Si, F.-J.; Wang, N.; Wang, T.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, W.; Luo, Y.-M.; Niu, D.-D.; Guo, J.-H.; et al. Bacillus-Secreted Oxalic Acid Induces Tomato Resistance Against Gray Mold Disease Caused by Botrytis cinerea by Activating the JA/ET Pathway. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2022, 35, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.W.; Baek, W.; Lim, S.; Han, S.-W.; Lee, S.C. Expression and Functional Roles of the Pepper Pathogen–Induced bZIP Transcription Factor CabZIP2 in Enhanced Disease Resistance to Bacterial Pathogen Infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interac. 2015, 28, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Dong, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, H. Identification of a xyloglucan-specific endo-(1-4)-beta-d-glucanase inhibitor protein from apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) as a potential defense gene against Botryosphaeria dothidea. Plant Sci. 2015, 231, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehela, Y.; Killiny, N. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Supplementation Boosts the Phytohormonal Profile in ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’-Infected Citrus. Plants 2023, 12, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Zhao, X.; Chen, M.; Fu, Y.; Xiang, M.; Chen, J. Effect of exogenous methyl jasmonate treatment on disease resistance of postharvest kiwifruit. Food Chem. 2020, 305, 125483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Kou, X.; Wu, C.; Fan, G.; Li, T. Methyl jasmonate induces the resistance of postharvest blueberry to gray mold caused by Botrytis cinerea. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4272–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Chen, J.-y.; Kuang, J.-f.; Lu, W.-j. Banana fruit NAC transcription factor MaNAC5 cooperates with MaWRKYs to enhance the expression of pathogenesis-related genes against Colletotrichum musae. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.J.P.; Brunings, A.; Peres, N.A.; Mou, Z.; Folta, K.M. The Arabidopsis NPR1 gene confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in strawberry. Transgenic Res. 2015, 24, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, G.M.; Sanfuentes, E.; Figueroa, P.M.; Figueroa, C.R. Independent Preharvest Applications of Methyl Jasmonate and Chitosan Elicit Differential Upregulation of Defense-Related Genes with Reduced Incidence of Gray Mold Decay during Postharvest Storage of Fragaria chiloensis Fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Sheng, X.; Iqbal, B.; Naeem, M.; Wang, N.; Li, F.; Yao, N.; Liu, X. Unraveling the functional characterization of a jasmonate-induced flavonoid biosynthetic CYP45082G24 gene in Carthamus tinctorius. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, K.; Zhou, Y. Construction and characterization of a high-quality cDNA library of Cymbidium faberi suitable for yeast one- and two-hybrid assays. BMC Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Ji, A.; Song, J.; Chen, S. Genome-wide analysis of auxin response factor gene family members in medicinal model plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. Biol. Open 2016, 5, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, R.; Ferreira, L.; Berger, D.K.; Myburg, A.A.; Naidoo, S. The identification and differential expression of Eucalyptus grandis pathogenesis-related genes in response to salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 00043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, A.S.; Faggion, S.A.; Hernandes, C.; Lourenço, M.V.; França, S.C.; Beleboni, R.O. Nematocidal effects of natural phytoregulators jasmonic acid and methyl-jasmonate against Pratylenchus zeae and Helicotylenchus spp. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 27, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Huang, K.; Pan, S.; Xu, T.; Tan, J.; Hao, D. Jasmonate induced terpene-based defense in Pinus massoniana depresses Monochamus alternatus adult feeding. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Liu, N.; Wang, F. Methyl jasmonate induced tolerance effect of Pinus koraiensis to Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves dos Santos, F.; Magalhães, D.M.A.; Luz, E.D.M.N.; Eberlin, M.N.; Simionato, A.V.C. Metabolite mass spectrometry profiling of cacao genotypes reveals contrasting resistances to Ceratocystis cacaofunesta phytopathogen. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 2519–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xie, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Han, W.; Wu, R.; Li, X.; Guan, Y.; et al. New Insights into Stress-Induced β-Ocimene Biosynthesis in Tea (Camellia sinensis) Leaves during Oolong Tea Processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11656–11664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J. Muscadinia rotundifolia ‘Noble’ defense response to Plasmopara viticola inoculation by inducing phytohormone-mediated stilbene accumulation. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasal-Slavik, T.; Eschweiler, J.; Kleist, E.; Mumm, R.; Goldbach, H.E.; Schouten, A.; Wildt, J. Early biotic stress detection in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) by BVOC emissions. Phytochemistry 2017, 144, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Guo, H.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Li, M.; Rashid, A.; Xu, C.; Wang, K. Methyl Jasmonate Promotes Phospholipid Remodeling and Jasmonic Acid Signaling to Alleviate Chilling Injury in Peach Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9958–9966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Zhao, L.; Wu, K.; Liu, C.; Deng, D.; Zhao, K.; Li, J.; Deng, A. Simultaneous detection of plant growth regulators jasmonic acid and methyl jasmonate in plant samples by a monoclonal antibody-based ELISA. Analyst 2020, 145, 4004–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Yang, N.; Ma, X.; Li, G.; Qian, M.; Ng, D.; Xia, K.; Gan, L. Plasma membrane H+-ATPase is involved in methyl jasmonate-induced root hair formation in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) seedlings. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.W.; Choi, H.R.; Solomon, T.; Jeong, C.S.; Lee, O.-H.; Tilahun, S. Preharvest Methyl Jasmonate Treatment Increased the Antioxidant Activity and Glucosinolate Contents of Hydroponically Grown Pak Choi. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tan, L.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Shi, C.; Wei, A.; Fei, X. Exogenous methyl jasmonate induces CHS and promotes flavonoid accumulation in Zanthoxylum bungeanum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I.; Krzemińska, M.; Grąbkowska, R.; Gomulski, J.; Żekanowski, C.; Gaweda-Walerych, K. Accumulation of Polyphenols and Associated Gene Expression in Hairy Roots of Salvia viridis Exposed to Methyl Jasmonate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginaldo, F.P.S.; Bueno, P.C.P.; Lourenço, E.M.G.; de Matos Costa, I.C.; Moreira, L.G.L.; de Araújo Roque, A.; Barbosa, E.G.; Fett-Neto, A.G.; Cavalheiro, A.J.; Giordani, R.B. Methyl jasmonate induces selaginellin accumulation in Selaginella convoluta. Metabolomics 2023, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Romdhane, A.; Chtourou, Y.; Sebii, H.; Baklouti, E.; Nasri, A.; Drira, R.; Maalej, M.; Drira, N.; Rival, A.; Fki, L. Methyl jasmonate induces oxidative/nitrosative stress and the accumulation of antioxidant metabolites in Phoenix dactylifera L. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 44, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mao, S.; Liang, M.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Huang, K.; Wu, Q. Preharvest Methyl Jasmonate Treatment Increased Glucosinolate Biosynthesis, Sulforaphane Accumulation, and Antioxidant Activity of Broccoli. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Hernández, E.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Selenium, Sulfur, and Methyl Jasmonate Treatments Improve the Accumulation of Lutein and Glucosinolates in Kale Sprouts. Plants 2022, 11, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Fang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Xin, H. The transcription factor VaNAC17 from grapevine (Vitis amurensis) enhances drought tolerance by modulating jasmonic acid biosynthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Tang, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Dong, Y.; Li, T. The effects of methyl jasmonate on growth, gene expression and metabolite accumulation in Isatis indigotica Fort. Indust. Crops Prod. 2022, 177, 114482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, S.; Warghat, A.R. Comparative analysis of salidroside and rosavin accumulation and expression analysis of biosynthetic genes in salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate elicited cell suspension culture of Rhodiola imbricata (Edgew.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 198, 116667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erst, A.A.; Petruk, A.A.; Erst, A.S.; Krivenko, D.A.; Filinova, N.V.; Maltseva, S.Y.; Kulikovskiy, M.S.; Banaev, E.V. Optimization of Biomass Accumulation and Production of Phenolic Compounds in Callus Cultures of Rhodiola rosea L. Using Design of Experiments. Plants 2022, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, P.; Szymańska, G.; Kuźma, Ł.; Jeleń, A.; Balcerczak, E. Methyl Jasmonate Activates the 2C Methyl-D-erithrytol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate Synthase Gene and Stimulates Tanshinone Accumulation in Salvia miltiorrhiza Solid Callus Cultures. Molecules 2022, 27, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, N.; Singh, S.; Saffeulla, P. Methyl jasmonate elicitation improved growth, antioxidant enzymes, and artemisinin content in in vitro callus cultures of Artemisia maritima L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 177, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeon, H.; Jang, E.B.; Kim, S.C.; Yoon, S.-A.; Go, B.; Lee, J.-D.; Hyun, H.B.; Ham, Y.-M. Metabolomics Reveals Rubiadin Accumulation and the Effects of Methyl Jasmonate Elicitation in Damnacanthus major Calli. Plants 2024, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, S.; Goulet, M.-C.; D’Aoust, M.-A.; Sainsbury, F.; Michaud, D. Leaf proteome rebalancing in Nicotiana benthamiana for upstream enrichment of a transiently expressed recombinant protein. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewski, M.; Szablińska-Piernik, J.; Marasek-Ciołakowska, A.; Mitrus, J.; Góraj-Koniarska, J.; Lahuta, L.B.; Wiczkowski, W.; Miyamoto, K.; Ueda, J.; Horbowicz, M. Accumulation of Anthocyanins in Detached Leaves of Kalanchoë blossfeldiana: Relevance to the Effect of Methyl Jasmonate on This Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Chi, M.; Guo, J.; Jia, H.; Zhang, C. Alleviation of cadmium toxicity and minimizing its accumulation in rice plants by methyl jasmonate: Performance and mechanisms. J. Biotechnol. 2025, 398, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.Y.; Yu, X.F.; Liu, Y.J.; Zeng, X.X.; Luo, F.W.; Wang, X.T.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.Y.; Xue, X.; Yang, L.J.; et al. Methyl jasmonate regulation of pectin polysaccharides in Cosmos bipinnatus roots: A mechanistic insight into alleviating cadmium toxicity. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 123503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, G.M.; Figueroa, N.E.; Poblete, L.A.; Cherian, S.; Figueroa, C.R. Effects of preharvest applications of methyl jasmonate and chitosan on postharvest decay, quality and chemical attributes of Fragaria chiloensis fruit. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, M.; Hasanlooe, A.R. Methyl jasmonate effectively enhanced some defense enzymes activity and Total Antioxidant content in harvested “Sabrosa” strawberry fruit. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.; Ruiz del Castillo, M.L. Accumulation of anthocyanins and flavonols in black currants (Ribes nigrum L.) by pre-harvest methyl jasmonate treatments. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4026–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, S.; Valero, D.; Serrano, M. Postharvest biology and technology of pomegranate. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2360–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.; Blanch, G.P.; del Castillo, M.L.R. Effect of postharvest methyl jasmonate treatment on fatty acid composition and phenolic acid content in olive fruits during storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2767–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Azam, M.; Noreen, A.; Umer, M.A.; Ilahy, R.; Akram, M.T.; Qadri, R.; Khan, M.A.; Rehman, S.u.; Hussain, I.; et al. Application of Methyl Jasmonate to Papaya Fruit Stored at Lower Temperature Attenuates Chilling Injury and Enhances the Antioxidant System to Maintain Quality. Foods 2023, 12, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, C.; Brummell, D.A.; Qi, S.; Lin, Q.; Duan, Y. Jasmonic acid treatment alleviates chilling injury in peach fruit by promoting sugar and ethylene metabolism. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.B.; Malviya, D.; Singh, S.; Kumar, M.; Sahu, P.K.; Singh, H.V.; Kumar, S.; Roy, M.; Imran, M.; Rai, J.P.; et al. Trichoderma harzianum- and Methyl Jasmonate-Induced Resistance to Bipolaris sorokiniana Through Enhanced Phenylpropanoid Activities in Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 01697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Castle del Conte, S.C. Methyl jasmonate induction of cotton: A field test of the ‘attract and reward’ strategy of conservation biological control. AoB Plants 2017, 9, plx032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.N.; Lin, C.P.; Hsieh, F.C.; Lee, S.K.; Cheng, K.C.; Liu, C.T. Characterization and evaluation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain WF02 regarding its biocontrol activities and genetic responses against bacterial wilt in two different resistant tomato cultivars. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikano, I.; Pan, Q.; Hoover, K.; Felton, G.W. Herbivore-Induced Defenses in Tomato Plants Enhance the Lethality of the Entomopathogenic Bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki. J. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 44, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moral, A.; Llorens, E.; Scalschi, L.; García-Agustín, P.; Trapero, A.; Agustí-Brisach, C. Resistance Induction in Olive Tree (Olea europaea) Against Verticillium Wilt by Two Beneficial Microorganisms and a Copper Phosphite Fertilizer. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 831794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, C.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, H. Positive interaction between melatonin and methyl jasmonate enhances Fusarium wilt resistance in Citrullus lanatus. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1508852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Fang, L.; Nopo-Olazabal, C.; Condori, J.; Nopo-Olazabal, L.; Balmaceda, C.; Medina-Bolivar, F. Enhanced Production of Resveratrol, Piceatannol, Arachidin-1, and Arachidin-3 in Hairy Root Cultures of Peanut Co-treated with Methyl Jasmonate and Cyclodextrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3942–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowacz, M.; Roets, N.; Sivakumar, D. Control of anthracnose disease via increased activity of defence related enzymes in ‘Hass’ avocado fruit treated with methyl jasmonate and methyl salicylate. Food Chem. 2017, 234, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, R.; Waqas, M.; Khan, A.L.; Hamayun, M.; Kang, S.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Foliar application of methyl jasmonate induced physio-hormonal changes in Pisum sativum under diverse temperature regimes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 96, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Hua, X.; Turlings, T.C.; Cheng, J.; Chen, X.; Ye, G. Differences in induced volatile emissions among rice varieties result in differential attraction and parasitism of Nilaparvata lugens eggs by the parasitoid Anagrus nilaparvatae in the field. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 32, 2375–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, M.; Silva Bueno, J.C. Within-plant signaling by volatiles leads to induction and priming of an indirect plant defense in nature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5467–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, J.A.; Aradottír, G.I.; Birkett, M.A.; Bruce, T.J.; Chamberlain, K.; Khan, Z.R.; Midega, C.A.; Smart, L.E.; Woodcock, C.M. Aspects of insect chemical ecology: Exploitation of reception and detection as tools for deception of pests and beneficial insects. Physiol. Entomol. 2014, 39, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, J.S.; Stout, M.J.; Karban, R.; Duffey, S.S. Exogenous jasmonates simulate insect wounding in tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum) in the laboratory and field. J. Chem. Ecol. 1996, 22, 1767–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamogami, S.; Rakwal, R.; Agrawal, G.K. Interplant communication: Airborne methyl jasmonate is essentially converted into JA and JA-Ile activating jasmonate signaling pathway and VOCs emission. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 376, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z.; Shi, H.; Naqvi, N.I.; Qian, Q.; Liang, Y.; Kou, Y. Warm temperature compromises JA-regulated basal resistance to enhance Magnaporthe oryzae infection in rice. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.W.; Dalen, L.S.; Skrautvol, T.O.; Ton, J.; Krokene, P.; Mageroy, M.H. Transcriptomic changes during the establishment of long-term methyl jasmonate-induced resistance in Norway spruce. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 1891–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Tao, F.; An, F.; Zou, Y.; Tian, W.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Hu, X. Wheat transcription factor TaWRKY70 is positively involved in high-temperature seedling plant resistance to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronopoulou, L.; Donati, L.; Bramosanti, M.; Rosciani, R.; Palocci, C.; Pasqua, G.; Valletta, A. Microfluidic synthesis of methyl jasmonate-loaded PLGA nanocarriers as a new strategy to improve natural defenses in Vitis vinifera. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Y.; Zou, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, X.; Fang, W.; Ma, Y. CsMYB Transcription Factors Participate in Jasmonic Acid Signal Transduction in Response to Cold Stress in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis). Plants 2022, 11, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, L.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Deng, J.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, S. MeJA-Induced Plant Disease Resistance: A Review. Plants 2026, 15, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010169

Xiao L, Li Y, Cui L, Deng J, Zhao Q, Yang Q, Zhao S. MeJA-Induced Plant Disease Resistance: A Review. Plants. 2026; 15(1):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010169

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Lifeng, Yuting Li, Lingyan Cui, Jie Deng, Qiuyue Zhao, Qin Yang, and Sifeng Zhao. 2026. "MeJA-Induced Plant Disease Resistance: A Review" Plants 15, no. 1: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010169

APA StyleXiao, L., Li, Y., Cui, L., Deng, J., Zhao, Q., Yang, Q., & Zhao, S. (2026). MeJA-Induced Plant Disease Resistance: A Review. Plants, 15(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010169