Study on the Susceptibility of Some Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars to the Pathogen Diaporthe amygdali

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

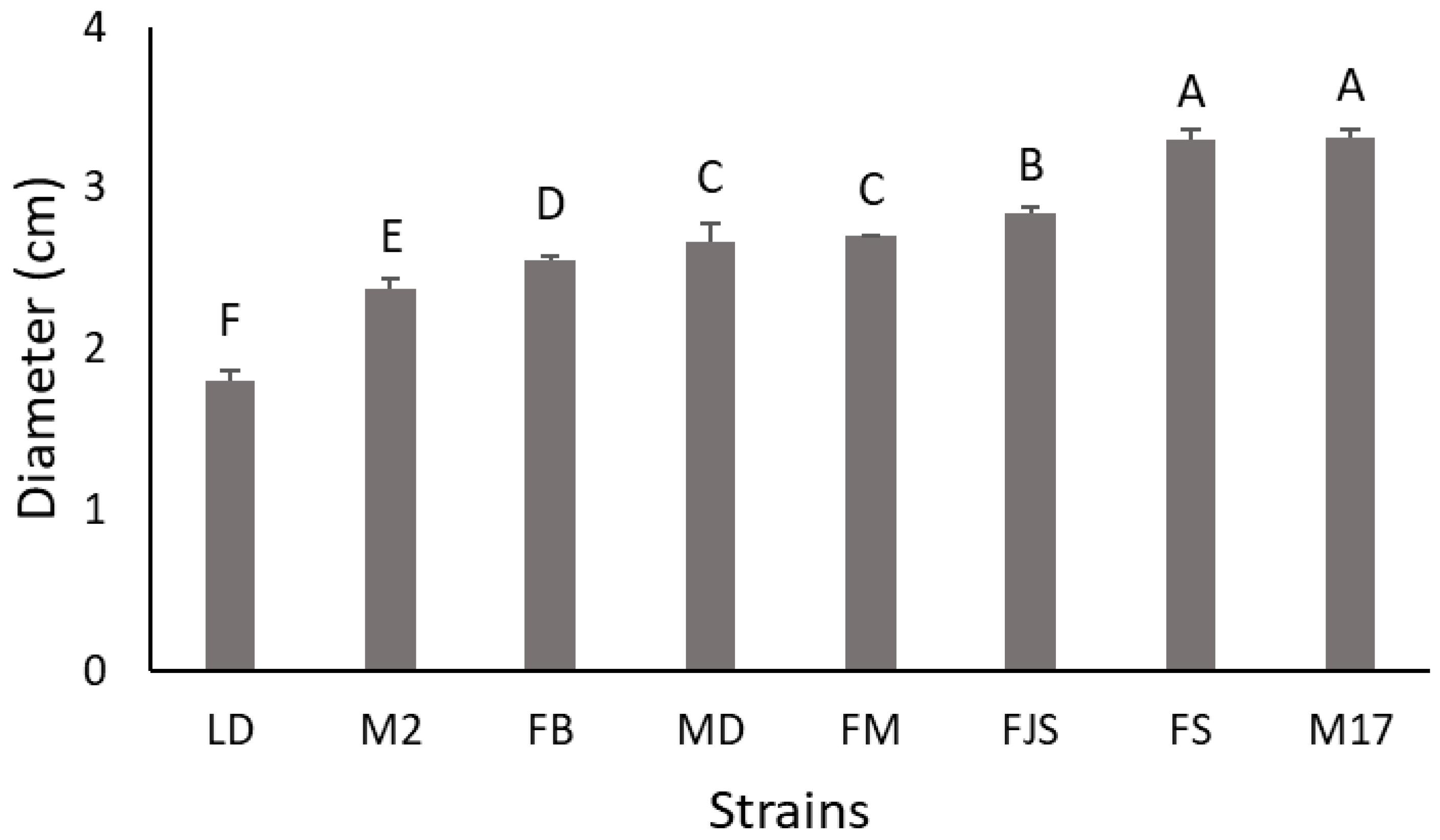

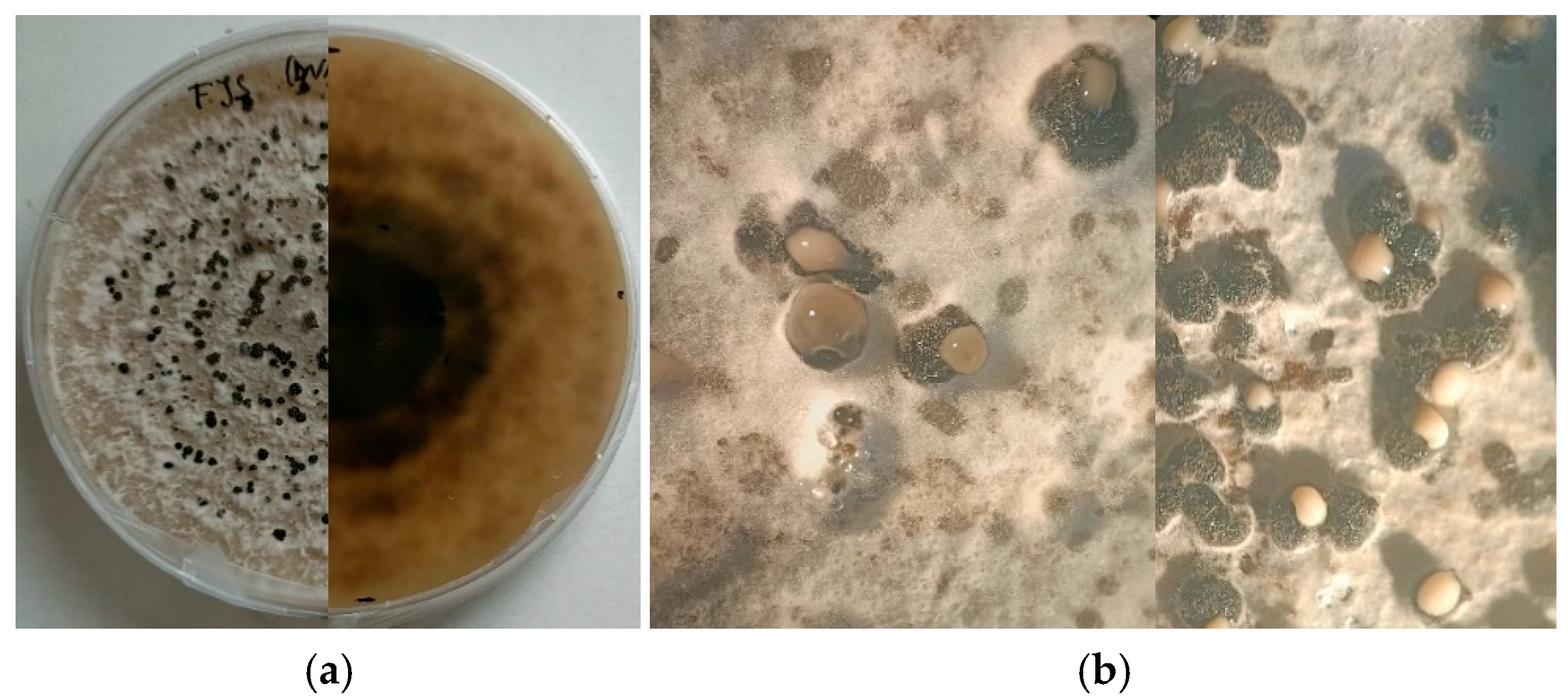

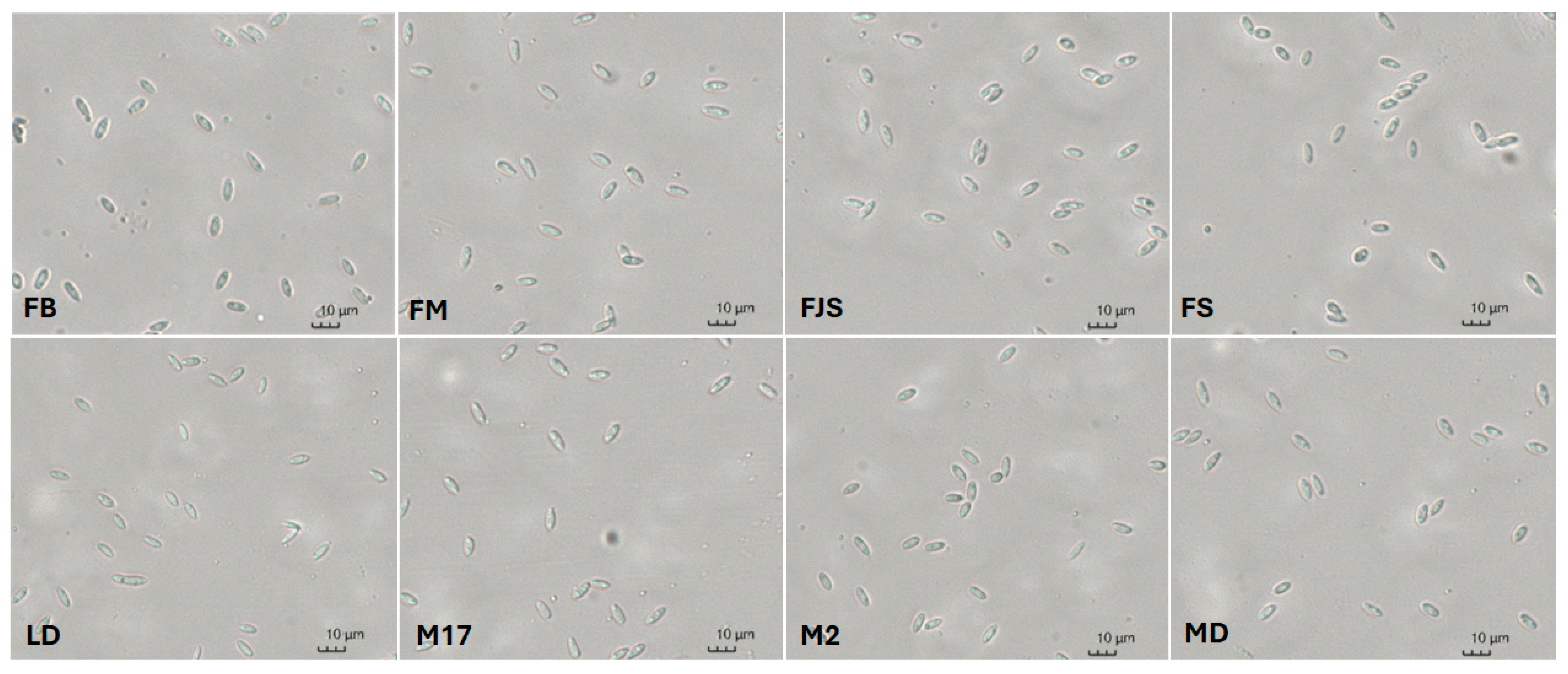

2.1. Isolation and Identification of the Pathogen

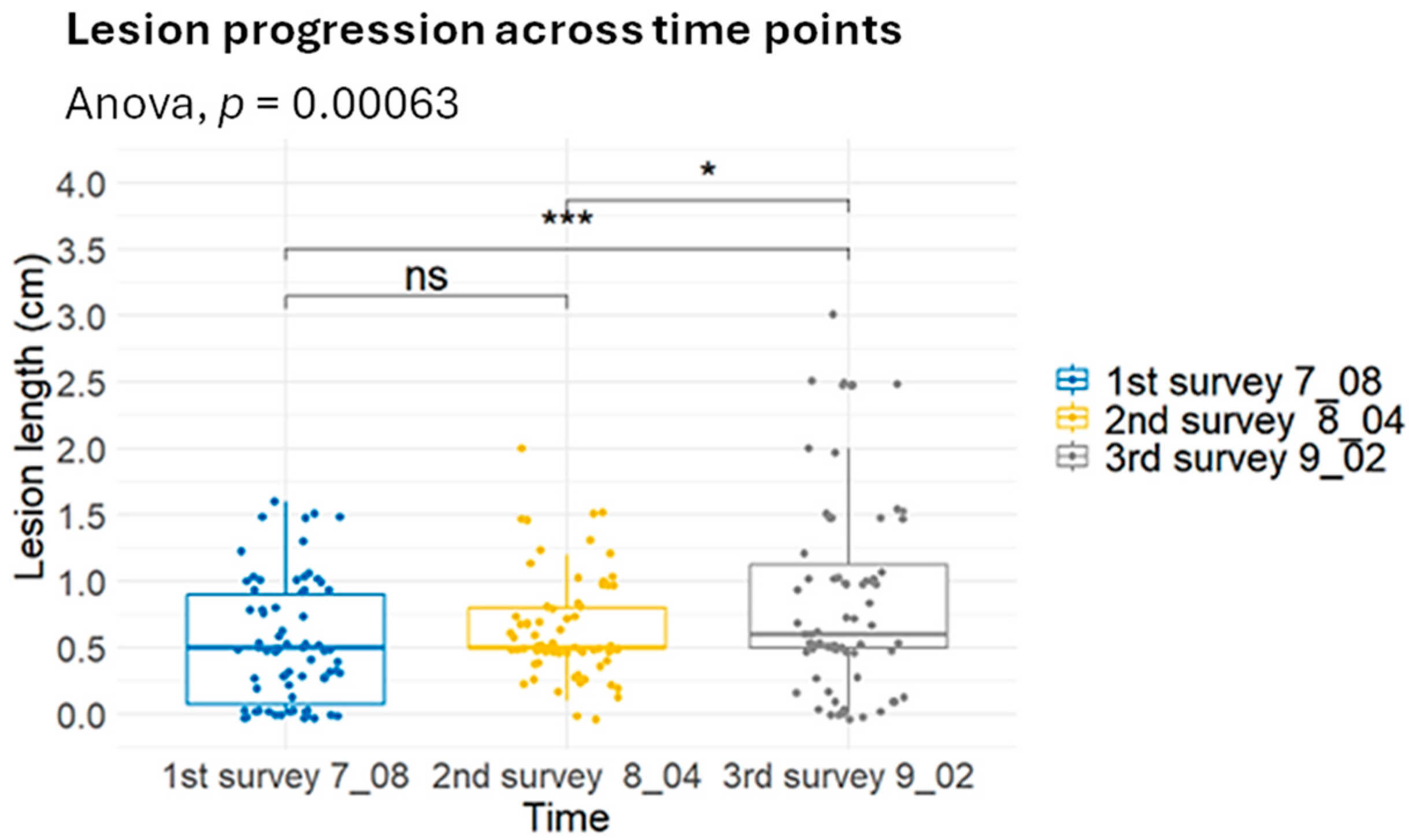

2.2. Inoculation Methods

2.3. Varietal Susceptibility

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Isolation, Morphological and Molecular Characterization

4.2. Plant Materials and Experimental Sites and Plot Design

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gradziel, T.M.; Curtis, R.; Socias I Company, R. Production and Growing Regions. In Almonds: Botany, Production and Uses; Rafel Socias i Company, Gradziel, T., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017; pp. 70–86. ISBN 978-1-78064-354-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kalita, S.; Khandelwal, S.; Madan, J.; Pandya, H.; Sesikeran, B.; Krishnaswamy, K. Almonds and Cardiovascular Health: A Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beluzán, F.; Miarnau, X.; Torguet, L.; Zazurca, L.; Abad-Campos, P.; Luque, J.; Armengol, J. Susceptibility of Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars to Twig Canker and Shoot Blight Caused by Diaporthe amygdali. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1890–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.; Pomar, L.T.; Girabet, R.; Zazurca, L.; García, G.M.; i Prim, X.M. Nuevos Modelos Productivos Para La Intensificación Del Almendro. Vida Rural. 2019, 472, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Faostat, F. Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database. 2020. Available online: www.faostat.org (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Gouk, C. Almond Diseases and Disorders. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 1109, Proceedings of the XXIX International Horticultural Congress on Horticulture: Sustaining Lives, Livelihoods and Landscapes (IHC2014): International Symposium on Nut Crops, Brisbane, Australia, 17–22 August 2014; Wirthensohn, M., Ed.; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2016; pp. 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Bielsa, A.; Cambra, M.; Martínez, C.; Olmos, A.; Pallás, V.; López, M.M.; Adaskaveg, J.E.; Förster, H.; Cambra, M.A.; Duval, H.; et al. Almond Diseases. In Almonds: Botany, Production and Uses; Rafel Socias i Company, Gradziel, T., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017; pp. 321–374. ISBN 978-1-78064-354-0. [Google Scholar]

- López-Moral, A.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Lovera, M.; Arquero, O.; Trapero, A. Almond Anthracnose: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Plants 2020, 9, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, L.A.; Trouillas, F.P.; Nouri, M.T.; Lawrence, D.P.; Crespo, M.; Doll, D.A.; Duncan, R.A.; Holtz, B.A.; Culumber, C.M.; Yaghmour, M.A.; et al. Fungal Pathogens Associated with Canker Diseases of Almond in California. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miarnau, X.; Zazurca, L.; Torguet, L.; Zúñiga, E.; Batlle, I.; Alegre, S.; Luque, J. Cultivar Susceptibility and Environmental Parameters Affecting Symptom Expression of Red Leaf Blotch of Almond in Spain. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollero-Lara, A.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Lovera, M.; Roca, L.F.; Arquero, O.; Trapero, A. Field Susceptibility of Almond Cultivars to the Four Most Common Aerial Fungal Diseases in Southern Spain. Crop Prot. 2019, 121, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moral, A.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Lovera, M.; Luque, F.; Roca, L.F.; Arquero, O.; Trapero, A. Effects of Cultivar Susceptibility, Fruit Maturity, Leaf Age, Fungal Isolate, and Temperature on Infection of Almond by Colletotrichum spp. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2425–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramaje, D.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; Moralejo, E.; Olmo, D.; Mostert, L.; Damm, U.; Armengol, J. Fungal Trunk Pathogens Associated with Wood Decay of Almond Trees on Mallorca (Spain). Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2012, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmo, D.; Armengol, J.; León, M.; Gramaje, D. Characterization and Pathogenicity of Botryosphaeriaceae Species Isolated from Almond Trees on the Island of Mallorca (Spain). Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 2483–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.M.; Raju, B.C.; Hung, H.Y.; Weisburg, W.G.; Man delco-Paul, L.; Brenner, D.J. Xylella fastidiosa gen. nov., sp. nov: Gram-Negative, Xylem-Limited, Fastidious Plant Bacteria Related to Xanthomonas spp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1987, 37, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, D.; Aprile, A.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A. Diseases caused by Xylella fastidiosa in Prunus genus: An overview of the research on an increasingly widespread pathogen. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 712452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montilon, V.; Potere, O.; Susca, L.; Mannerucci, F.; Nigro, F.; Pollastro, S.; Loconsole, G.; Palmisano, F.; Zaza, C.; Cantatore, M.; et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of a Xylella fastidiosa subsp. multiplex strain from almond (Prunus dulcis) in Apulia, Southern Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2024, 63, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailides, T.J.; Inderbitzin, P.; Connell, J.H.; Luo, Y.G.; Morgan, D.P.; Puckett, R.D. Understanding Band Canker of Almond Caused by Botryosphaeriaceae Fungi and Attempts to Control the Disease in California. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 1219, Proceedings of the VII International Symposium on Almonds and Pistachios, Adelaide, Australia, 5–9 November 2017; Wirthensohn, M.G., Ed.; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2018; pp. 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goura, K.; Lahlali, R.; Bouchane, O.; Baala, M.; Radouane, N.; Kenfaoui, J.; Ezrari, S.; El Hamss, H.; El Alami, N.; Amiri, S.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Fungal Pathogens Causing Trunk and Branch Cankers of Almond Trees in Morocco. Agronomy 2023, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaskaveg, J.E. Phomopsis Canker and Fruit Rot. In Compendium of Nut Crop Diseases in Temperate Zones; Teviotdale, B.L., Michailides, T.J., Pscheidt, J.W., Eds.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2002; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, E.L.; Santos, J.M.; Phillips, A.J. Phylogeny, Morphology and Pathogenicity of Diaporthe and Phomopsis Species on Almond in Portugal. Fungal Divers. 2010, 104, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuset, J.J.; Portilla, M.A.T. Taxonomic Status of Fusicoccum amygdali and Phomopsis amygdalina. Can. J. Bot. 1989, 67, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjas, V.; Izsépi, F.; Nagy, G.; Pájtli, É.; Vajna, L. Phomopsis Blight on Almond in Hungary (Pathogen: Phomopsis amygdali, Teleomorph: Diaporthe amygdali). Növényvédelem 2017, 53, 532–538. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr, E.I. Constriction cancker. In Compendium of Stone Fruit Diseases; Ogawa, J.M., Zehr, E.I., Bird, G.W., Ritchie, D.F., Uriu, K., Uyemoto, J.K., Eds.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1995; pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Adaskaveg, J.E.; Förster, H.; Connell, J.H. First Report of Fruit Rot and Associated Branch Dieback of Almond in California Caused by a Phomopsis species Tentatively Identified as P. amygdali. Plant Dis. 1999, 83, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beluzán, F.; Olmo, D.; León, M.; Abad-Campos, P.; Armengol, J. First Report of Diaporthe amygdali Associated with Twig Canker and Shoot Blight of Nectarine in Spain. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besoain, X.; Briceno, E.; Piontelli, E. Fusicoccum sp. as the Cause of Canker in Almond Trees and Susceptibility of Three Cultivars. Fitopatología 2000, 35, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrita, L.; Neves, A.; Leitão, J. Evaluation of Resistance to Phomopsis amygdali in Almond. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 663, 2, Proceedings of the XI Eucarpia Symposium on Fruit Breeding and Genetics, Angers, France, 1–5 September 2003; Laurens, F., Evans, K., Eds.; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2004; pp. 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, F.M.; Zeng, R.; Lu, J.P. First Report of Twig Canker on Peach Caused by Phomopsis amygdali in China. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, D.F.; Castlebury, L.A.; Pardo-Schultheiss, R.A. Phomopsis amygdali Causes Peach Shoot Blight of Cultivated Peach Trees in the Southeastern United States. Mycologia 1999, 91, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, M.; Berbegal, M.; Rodríguez-Reina, J.M.; Elena, G.; Abad-Campos, P.; Ramón-Albalat, A.; Olmo, D.; Vicent, A.; Luque, J.; Miarnau, X.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Diaporthe spp. Associated with Twig Cankers and Shoot Blight of Almonds in Spain. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailides, T.J.; Thomidis, T. First Report of Phomopsis amygdali Causing Fruit Rot on Peaches in Greece. Plant Dis. 2006, 90, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, W.; Stevenson, K.L. Seasonal Development of Phomopsis Shoot Blight of Peach and Effects of Selective Pruning and Shoot Debris Management on Disease Incidence. Plant Dis. 1998, 82, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjas, V.; Vajna, L.; Izsépi, F.; Nagy, G.; Pájtli, É. First Report of Phomopsis amygdali Causing Twig Canker on Almond in Hungary. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, L.; Crous, P.W.; Kang, J.-C.; Phillips, A.J.L. Species of Phomopsis and a Libertella sp. Occurring on Grapevines with Specific Reference to South Africa: Morphological, Cultural, Molecular and Pathological Characterization. Mycologia 2001, 93, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienapfl, J.C.; Balci, Y. Phomopsis Blight: A New Disease of Pieris japonica Caused by Phomopsis amygdali in the United States. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Zhai, L.; Chen, X.; Hong, N.; Xu, W.; Wang, G. Biological and Molecular Characterization of Five Phomopsis Species Associated with Pear Shoot Canker in China. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilário, S.; Santos, L.; Alves, A. Diversity and Pathogenicity of Diaporthe Species Revealed from a Survey of Blueberry Orchards in Portugal. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalancette, N.; Robison, D.M. Seasonal Availability of Inoculum for Constriction Canker of Peach in New Jersey. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalancette, N.; Foster, K.A.; Robison, D.M. Quantitative Models for Describing Temperature and Moisture Effects on Sporulation of Phomopsis amygdali on Peach. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaskaveg, J.E.; Schnabel, G.; Förster, H. Diseases of Peach Caused by Fungi and Fungal-like Organisms: Biology, Epidemiology and Management. In The Peach: Botany, Production and Uses; Layne, D., Bassi, D., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 352–406. ISBN 978-1-84593-386-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, S.; Caddoux, L.; Remuson, F.; Barrès, B. Thiophanate-methyl and Carbendazim Resistance in Fusicoccum amygdali, the Causal Agent of Constriction Canker of Peach and Almond. Plant Pathol. 2022, 71, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, L.; Garcia, J.E.; Egea, J.; Berenguer, T. Premieres Observations Sur Une Collection de 81 Varietes d’amandiers Situee Dans Le Sud-Est Espagnol [Polystigma Occhraceum, Coryneum Beijerincii, Puccinia Pruni-Spinosa; Monosteria Unicostata]. In Options Mediterraneennes (France). No. 2., Proceedings of the 5. Reunion du GREMPA, Sfax Tunisia, 2–7 May 1983; CIHEAM: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gradziel, T.M.; Wang, D. Susceptibility of California Almond Cultivars to Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus. HortScience 1994, 29, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diéguez-Uribeondo, J.; Förster, H.; Adaskaveg, J.E. Effect of Wetness Duration and Temperature on the Development of Anthracnose on Selected Almond Tissues and Comparison of Cultivar Susceptibility. Phytopathology 2011, 101, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsfield, A.; Wicks, T. Susceptibility of Almond Cultivars to Tranzschelia discolor. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2014, 43, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, F.J.; Miarnau, X. Field Susceptibility to Fusicoccum Canker of Almond Cultivars. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 912, Proceedings of the V International Symposium on Pistachios and Almonds, Sanliurfa, Turkey, 6–10 October 2009; Ak, B.E., Wirthensohn, M., Gradziel, T., Eds.; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2011; pp. 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella, G.; La Quatra, G.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Trapero, A.; Polizzi, G. Elucidating the Almond Constriction Canker Caused by Diaporthe amygdali in Sicily (South Italy). J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 105, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piglionica, V. Resistenza di cultivar pugliesi di Mandorlo (Prunus amygdalus Stokes) a Fusicoccum amygdali Del. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 1967, 6, 138–143. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42683780 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Catalano, C.; Gusella, G.; Inzirillo, I.; Cannizzaro, G.; Di Guardo, M.; La Malfa, S.; Polizzi, G.; Gentile, A.; Distefano, G. Exploring Additive and Non-Additive Genetic Models to Decipher the Genetic Regulation of Almond Tolerance to Diaporthe amygdali. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1608958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayanga, D.; Liu, X.; Crous, P.W.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Chukeatirote, E.; Hyde, K.D. A Multi-Locus Phylogenetic Evaluation of Diaporthe (Phomopsis). Fungal Divers. 2012, 56, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayanga, D.; Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Hyde, K.D. Species Limits in Diaporthe: Molecular Re-Assessment of D. Citri, D. Cytosporella, D. Foeniculina and D. Rudis. Persoonia-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2014, 32, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, Z.; Huang, X.; Hong, N.; Xu, W.; Wang, G. Characterization of Diaporthe Species Associated with Peach Constriction Canker, with Two Novel Species from China. MycoKeys 2021, 80, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilário, S.; Santos, L.; Alves, A. Diaporthe amygdali, a Species Complex or a Complex Species? Fungal Biol. 2021, 125, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Sharma, K.; Misra, R.S. Rapid and efficient method for the extraction of fungal and oomycetes genomic DNA. Genes Genomes Genom. 2008, 2, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, A.; Crous, P.W.; Correia, A.; Phillips, A.J.L. Morphological and Molecular Data Reveal Cryptic Speciation in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Fungal Divers. 2008, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Travadon, R.; Lawrence, D.P.; Rooney-Latham, S.; Gubler, W.D.; Wilcox, W.F.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Baumgartner, K. Cadophora Species Associated with Wood-Decay of Grapevine in North America. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Groenewald, M.; Caldwell, P.; Braun, U.; Harrington, T.C. Species of Cercospora Associated with Grey Leaf Spot of Maize. Stud. Mycol. 2006, 55, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Johnston, P.R.; Damm, U. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Species Complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 115–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the Number of Nucleotide Substitutions in the Control Region of Mitochondrial DNA in Humans and Chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence Limits on Phylogenies: An Approach Using the Bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, H.; Coindre, E.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Alexiou, K.G.; Rubio-Cabetas, M.J.; Martínez-García, P.J.; Wirthensohn, M.; Dhingra, A.; Samarina, A.; Arús, P. Development and Evaluation of an AxiomTM 60K SNP Array for Almond (Prunus dulcis). Plants 2023, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Orchard Location | Year of Isolation | Variety | ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borgho (2B), Corsica, France | 2018 | Unknown | M2 ref 18-286 |

| Borgho (2B), Corsica, France | 2018 | Unknown | M17 ref 18-286 |

| Charolles (26), France | 2022 | Lauranne | LD |

| Charolles (26), France | 2022 | Mandaline | MD |

| St Didier (84), France | 2022 | Ferragnès | FS |

| Manduel (30), France | 2022 | Ferragnès | FB |

| Donzere (26), France | 2025 | Ferragnès | FM |

| St Didier (84), France | 2025 | Ferragnès | FJS |

| Conidia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Width (µm) | Tukey HSD Test | Length (µm) | Tukey HSD Test | Isolate |

| 2.6 ± 0.1 | BCD | 7.4 ± 0.2 | B | FB |

| 3.1 ± 0.1 | A | 8.7 ± 0.4 | A | FJS |

| 2.6 ± 0.1 | BCD | 6.6 ± 0.3 | B | FM |

| 2.7 ± 0.1 | ABC | 7.2 ± 0.2 | B | FS |

| 2.3 ± 0.1 | D | 7.3 ± 0.3 | B | LD |

| 2.5 ± 0.1 | BCD | 6.9 ± 0.3 | B | M2 |

| 2.5 ± 0.1 | CD | 7.9 ± 0.3 | AB | M17 |

| 2.9 ± 0.1 | AB | 9.1 ± 0.4 | A | MD |

| Code No. | Variety | Country * | Flowering Season ** | Resistance Level to D. amygdali | Inoculum Method *** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||||

| R486 | Ferragnès | FRA | 4 | S | X | X | X |

| R1877 | Hybride R1877 | FRA | 5 | X | |||

| R916 | Lauranne | FRA | 5 | X | |||

| R800 | Ferrastar | FRA | 5 | T | X | X | X |

| R61 | Ardèchoise | FRA | 3 | T | X | X | X |

| R185 | Marcona | ESP | 2 | X | |||

| R1046 | Princesse-JR | FRA | 2 | X | |||

| R934 | Guara | ITA | 5 | X | |||

| R998 | Mandaline | FRA | 5 | X | |||

| R219 | Tuono | ITA | 4 | S | X | X | X |

| R993 | Hybride R993 | FRA | 5 | X | |||

| R1590 | Le plan1 | FRA | 4 | X | |||

| R1568 | Hybride R1568 | FRA | 5 | X | |||

| R270 | Texas | USA | 4 | T | X | X | X |

| R1413 | Hybride R1413 | FRA | 7 | X | |||

| R1542 | Hybride R1542 | FRA | 5 | X | |||

| R860 | Filippo Ceo | ITA | 4 | I | X | ||

| R1591 | Le plan2 | FRA | 5 | X | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lucchese, P.G.; Dlalah, N.; Buisine, A.; Nigro, F.; Pollastro, S.; Duval, H. Study on the Susceptibility of Some Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars to the Pathogen Diaporthe amygdali. Plants 2026, 15, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010165

Lucchese PG, Dlalah N, Buisine A, Nigro F, Pollastro S, Duval H. Study on the Susceptibility of Some Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars to the Pathogen Diaporthe amygdali. Plants. 2026; 15(1):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010165

Chicago/Turabian StyleLucchese, Pompea Gabriella, Naïma Dlalah, Amélie Buisine, Franco Nigro, Stefania Pollastro, and Henri Duval. 2026. "Study on the Susceptibility of Some Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars to the Pathogen Diaporthe amygdali" Plants 15, no. 1: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010165

APA StyleLucchese, P. G., Dlalah, N., Buisine, A., Nigro, F., Pollastro, S., & Duval, H. (2026). Study on the Susceptibility of Some Almond (Prunus dulcis) Cultivars to the Pathogen Diaporthe amygdali. Plants, 15(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010165