Eco-Physiological and Molecular Roles of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) in Mitigating Abiotic Stress: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Climate Change, Abiotic Stress, and Plant Eco-Physiology

3. ZnO-NPs: Properties and Potential

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of ZnO-NPs

3.2. Influence of ZnO-NP Surface Chemistry on Zn2+ Availability, Redox Balance, and Photoprotection

3.3. Comparison with Conventional Sources of Zn

3.4. Absorption and Transport Mechanisms

3.5. Environmental and Safety Considerations

4. Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Tolerance Induced by ZnO-NPs

4.1. Regulation of ROS and Antioxidant Systems Using ZnO-NPs

4.2. Photosynthesis and PSII

4.3. Nitrogen and Carbon Metabolism

4.4. Hormonal Signaling

4.5. Genes and Transcriptomics

5. Experimental Evidence in Crops Under Abiotic Stress

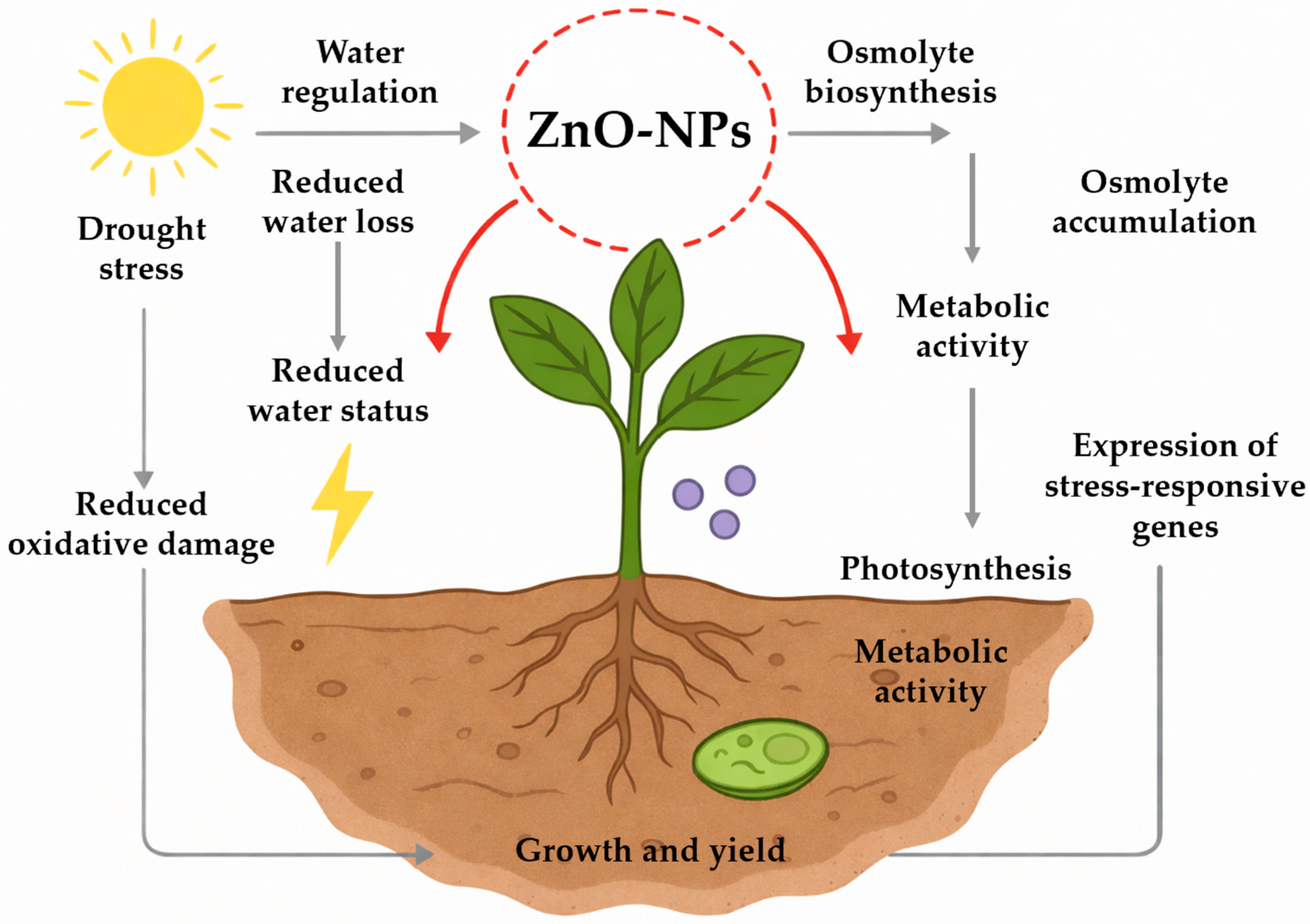

5.1. Drought Stress and the Role of ZnO-NPs

5.2. Salinity Stress and the Role of ZnO-NPs

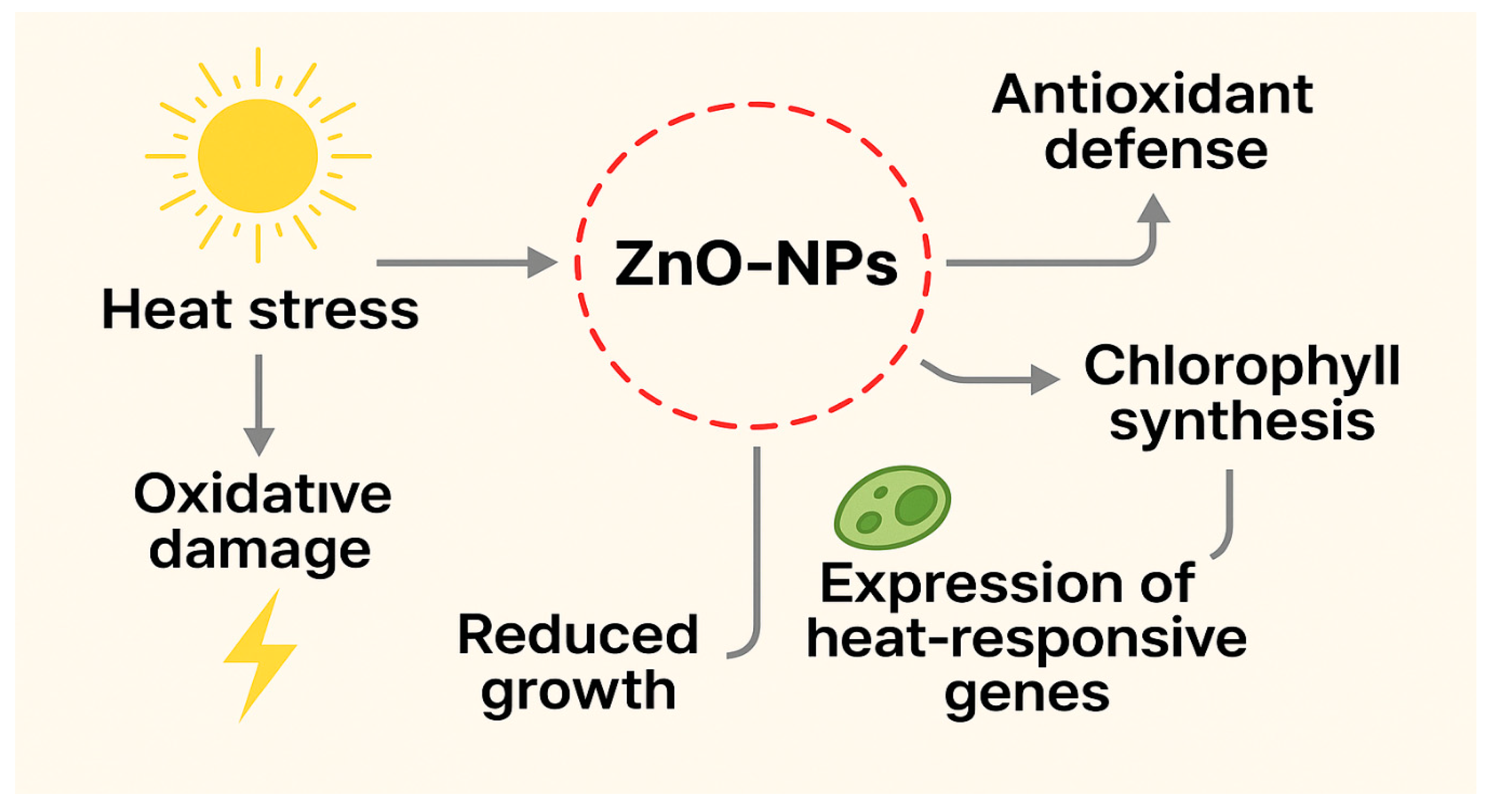

5.3. Heat Stress and the Role of ZnO-NPs

5.4. Heavy Metals Stress and the Role of ZnO-NPs

6. Eco-Physiological Role of ZnO-NPs Under Climate Change

6.1. Eco-Physiological Perspective in Climate Change Scenarios

6.2. ZnO-NPs as a Tool for Climate Resilience

6.3. Possibilities in Protected and Open-Air Agriculture

6.4. Relationship to Food Security and Sustainability

7. Limitations and Future Challenges

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| AsA | Ascorbate–glutathione cycle |

| AsA-GSH cycle | Ascorbate–glutathione cycle |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CKs | Cytokinins |

| ETR | Electron transport rate |

| Fv/Fm | Maximum quantum efficiency of PSII |

| ΦPSII (PhiPSII) | Effective quantum yield of PSII |

| GOGAT | Glutamate synthase |

| GPX | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| HM | Heavy metals |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| NR | Nitrate reductase |

| PGPR | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| PSI (P700) | Photosystem I reaction center chlorophyll |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| qP | Photochemical quenching coefficient |

| RCA | Rubisco activase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Rubisco | Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| ZnO-NPs | Zinc oxide nanoparticles |

References

- Sánchez-Bermúdez, M.; Del Pozo, J.C.; Pernas, M. Effects of combined abiotic stresses related to climate change on root growth in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 918537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibi, F.; Rahman, A. An Overview of Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture and Their Mitigation Strategies. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Ao, X. Impacts of global climate change on agricultural production: A comprehensive review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Tóth, Z.; Rizk, R.; Abdul-Hamid, D.; Decsi, K. Investigation of Antioxidative Enzymes and Transcriptomic Analysis in Response to Foliar Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Salinity Stress in Solanum lycopersicum. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Afzal, S.; Yadav, R.; Singh, N.K.; Zarbakhsh, S. Salinity stress amelioration through selenium and zinc oxide nanoparticles in rice. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H.U.; Ali, W.; Uddin, M.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, K.; Bibi, H.; Alatalo, J.M. Abiotic stresses in soils, their effects on plants, and mitigation strategies: A literature review. Chem. Ecol. 2025, 41, 552–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, A.; Mai, W.; Gul, B.; Rasheed, A. Eco-physiological and growth responses of two halophytes to saline irrigation and soil amendments in arid conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ali, I. Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms of Nitrogen Assimilation in C3 plants under Abiotic Stress: A Mini Review. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 94, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, P. Symbiotic Nodulation Enhances Legume Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Plant Cell Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaib, M.; Zubair, M.; Aryan, M.; Abdullah, M.; Manzoor, S.; Masood, F.; Saeed, S. A review on challenges and opportunities of fertilizer use efficiency and their role in sustainable agriculture with future prospects and recommendations. Curr. Res. Agric. Farm. 2023, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.-Q.; Hayat, Z.; Zhang, D.-D.; Li, M.-Y.; Hu, S.; Wu, Q.; Cao, Y.-F.; Yuan, Y. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Modification, and Applications in Food and Agriculture. Processes 2023, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. Toxicity and transport of nanoparticles in agriculture: Effects of size, coating, and aging. Front. Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 1622228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Geng, H.; Zhou, B.; Chen, H.; Yuan, R.; Ma, C.; Liu, R.; Xing, B.; Wang, F. The behavior, transport, and positive regulation mechanism of ZnO nanoparticles in a plant-soil-microbe environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, N.C.T.; Avellan, A.; Rodrigues, S. Composites of biopolymers and ZnO NPs for controlled release of zinc in agricultural soils and timed delivery for maize. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, T.N.; Savassa, S.M.; Montanha, G.S.; Ishida, J.K.; de Almeida, E.; Tsai, S.M.; Junior, J.L.; Pereira de Carvalho, H.W. A new glance on root-to-shoot in vivo zinc transport and time-dependent physiological effects of ZnSO4 and ZnO nanoparticles on plants. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirakhorli, T.; Ardebili, Z.O.; Ladan-Moghadam, A.; Danaee, E. Bulk and nanoparticles of zinc oxide exerted their beneficial effects by conferring modifications in transcription factors, histone deacetylase, carbon and nitrogen assimilation, antioxidant biomarkers, and secondary metabolism in soybean. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, M.T.; Abbasi, A.; Haq, I.U.; Hina, A.; Mohiuddin, M.; Tariq, M.A.U.R.; Afzal, M.Z.; Zaman, Q.U.; Ng, A.W.M.; et al. Characterizing stomatal attributes and photosynthetic induction in relation to biochemical changes in Coriandrum sativum L. by foliar-applied zinc oxide nanoparticles under drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 13, 1079283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, M.; Bhat, J.A.; Chen, C.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wijaya, L.; Ahmad, P.; Yu, F. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) induce salt tolerance by improving the antioxidant system and photosynthetic machinery in tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 161, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimian, Z.; Samiei, L. ZnO nanoparticles efficiently enhance drought tolerance in Dracocephalum kotschyi through altering physiological, biochemical and elemental contents. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1063618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.; Chaudhari, S.K.; Manzoor, M.; Batool, S.; Hatami, M.; Hasan, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles mediated salinity stress mitigation in Pisum sativum: A physio-biochemical perspective. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Sedaghat, A.; Esmaeili, M. Zinc in Plants: Biochemical Functions and Dependent Signaling. In Metals and Metalloids in Plant Signaling (Signaling and Communication in Plants); Aftab, T., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadley, M.R.; White, P.J.; Hammond, J.P.; Zelko, I.; Lux, A. Zinc in plants. New Phytol. 2007, 173, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thabet, S.G.; Alqudah, A.M. Unraveling the role of nanoparticles in improving plant resilience under environmental stress condition. Plant Soil 2024, 503, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, H.F.; Afroze, B.; Shakoor, S.; Bhutta, M.S.; Ahmed, M.; Hassan, S.; Batool, F.; Rashid, B. Nanoparticles in Agriculture: Enhancing Crop Resilience and Productivity against Abiotic Stresses. In Abiotic Stress in Crop Plants—Ecophysiological Responses and Molecular Approaches; Hasanuzzaman, M., Nahar, K., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, S.; Abbasi, B.A.; Iqbal, J.; Ullah, Z.; Ijaz, N.; Shah, N.H.; Khan, S.; Ashraf, Z.; Murtaza, G.; Iqbal, R.; et al. Exploring the Interaction of Nanomaterials with Crops Based on Multiple OMICS Tools. In Stress-Resilient Crops: Coordinated Omics-CRISPR-Nanotechnology Strategies; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2025; pp. 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani-Naghani, S.; Fallah, S.; Pokhrel, L.R.; Rostamnejadi, A. Drought stress mitigation and improved yield in Glycine max through foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, S.; Sajjad, A.; Javed, R.; Zia, M. The role of proline and betaine functionalized zinc oxide nanoparticles as drought stress regulators in Coriandrum sativum: An in vivo study. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.S.; Muhammad, F.; Farooq, M.; Aslam, M.U.; Akhter, N.; Toleikienė, M.; Abdulaziz-Binobead, M.; Ajmal-Ali, M.; Rzwan, M.; Iqbal, R. ZnO-nanoparticles and stage-based drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): Effect on morpho-physiology, nutrients uptake, grain yield and quality. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Marrez, D.A.; Rizk, R.; Zedan, M.; Abdul-Hamid, D.; Decsi, K.; Kovács, G.P.; Tóth, Z. The influence of zinc oxide nanoparticles and salt stress on the morphological and some biochemical characteristics of Solanum lycopersicum L. plants. Plants 2024, 13, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Choi, S.; Leskovar, D.I. SiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles and salinity stress responses in hydroponic lettuce: Selectivity, antagonism, and interactive dynamics. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1634675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa-Chaparro, E.H.; Patiño-Cruz, J.J.; Anchondo-Páez, J.C.; Pérez-Álvarez, S.; Chávez-Mendoza, C.; Castruita-Esparza, L.U.; Márquez, E.M.; Sánchez, E. Seed Nanopriming with ZnO and SiO2 Enhances Germination, Seedling Vigor, and Antioxidant Defense Under Drought Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Niu, T.; Tang, C.; Wang, C.; Xie, J. Zinc oxide nanoparticles improve lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) plant tolerance to cadmium by stimulating antioxidant defense, enhancing lignin content and reducing the metal accumulation and translocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1015745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrish, A.K.; Ahmad, S.; Alomrani, S.O.; Ahmad, A.; Al-Ghanim, K.A.; Alshehri, M.A.; Tauqeer, A.; Ali, S.; Sarker, P.K. Nutrient strengthening and lead alleviation in Brassica napus L. by foliar ZnO and TiO2-NPs modulating antioxidant system, improving photosynthetic efficiency and reducing lead uptake. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair Hassan, M.; Huang, G.; Haider, F.U.; Khan, T.A.; Noor, M.A.; Luo, F.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, B.; Ul Haq, M.I.; Iqbal, M.M. Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles to Mitigate Cadmium Toxicity: Mechanisms and Future Prospects. Plants 2024, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, S.; Nazir, M.M.; Ali, Q.; Zulfiqar, F.; Moosa, A.; Altaf, M.A.; Zaid, A.; Nafees, M.; Yong, J.W.H.; Jin, X. Zinc and nano zinc mediated alleviation of heavy metals and metalloids in plants: An overview. Funct. Plant Biol. 2023, 50, 870–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, A.; Emamverdian, A.; Pehlivan, N.; Zargar, M.; Razavi, S.M.; Chen, M. Nano-enabled agrochemicals: Mitigating heavy metal toxicity and enhancing crop adaptability for sustainable crop production. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareem, H.A.; Saleem, M.F.; Saleem, S.; Rather, S.A.; Wani, S.H.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Alamri, S.; Kumar, R.; Gaikwad, N.B.; Guo, Z.; et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles interplay with physiological and biochemical attributes in terminal heat stress alleviation in mungbean (Vigna radiata L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 842349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.; Asthir, B.; Kaur, G.; Kalia, A.; Sharma, A. Zinc oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles influence heat stress tolerance mediated by antioxidant defense system in wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 2022, 50, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Shah, S.; Bayar, J.; Korany, S.M.; Ahmad, U.; Gul, A.; Khan, W.; Jalal, A.; Alsherif, E.A.; Ali, N.; et al. Influence of zinc nanoparticles on maize productivity under heat stress caused by climate variability. Glob. NEST J. 2025, 27, 07370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, T.; Liang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Yang, F. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Applications in Enhancing Plant Stress Resistance: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejam, F.; Ardebili, Z.O.; Ladan-Moghadam, A.; Danaee, E. Zinc oxide nanoparticles mediated substantial physiological and molecular changes in tomato. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Decsi, K.; Tóth, Z. Different Tactics of Synthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles, Homeostasis Ions, and Phytohormones as Regulators and Adaptatively Parameters to Alleviate the Adverse Effects of Salinity Stress on Plants. Life 2023, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Rasheed, Y.; Ashraf, H.; Asif, K.; Maqsood, M.F.; Shahbaz, M.; Zulfiqar, I.; Farhat, F.; Nawaz, S.; Ahmad, M. Nanoparticle-mediated phytohormone interplay: Advancing plant resilience to abiotic stresses. J. Crop Health 2025, 77, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ali, B.; Sajid, I.A.; Ahmad, S.; Yousaf, M.A.; Ulhassan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ali, S.; Zhou, W.; Mao, B. Synergistic effects of exogenous melatonin and zinc oxide nanoparticles in alleviating cobalt stress in Brassica napus: Insights from stress-related markers and antioxidant machinery. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.M.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Sharma, P. Nanoparticle-mediated mitigation of salt stress-induced oxidative damage in plants: Insights into signaling, gene expression, and antioxidant mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 2983–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Gulzar, W.; Abideen, Z.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; El-Keblawy, A.; Zhao, F. Plant–Nanoparticle Interactions: Transcriptomic and Proteomic Insights. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Keller, A.A. Omics to address the opportunities and challenges of nanotechnology in agriculture. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 2595–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Oraon, P.K.; Malik, G.; Singh, S.P.; Gupta, A. Emerging Research in Nanotechnology, Metagenomics, and Other Omics-Based Technologies for Rhizosphere Management and Increased Plant Growth and Productivity. In Rhizosphere Engineering and Stress Resilience in Plants: Concepts and Applications; Malhotra, P., Mukherjee, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrovyan, A.; Vodovnik, M.; Mortimer, M. Omics approaches in environmental effect assessment of engineered nanomaterials and nanoplastics. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 2551–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, M.; Wang, Y.; Holden, P.A. Molecular mechanisms of nanomaterial-bacterial interactions revealed by omics—The role of nanomaterial effect level. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 683520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Shalmani, A.; Ali, M.; Yang, Q.H.; Ahmad, H.; Li, F.B. Mechanisms regulating the dynamics of photosynthesis under abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 615942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Sun, H.; Ma, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, H.; Mei, L. Effects of drought stress on photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport chain in young apple tree leaves. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio035279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species: Generation, Signaling, and Defense Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rajput, V.D.; Lalotra, S.; Agrawal, S.; Ghazaryan, K.; Singh, J.; Minkina, T.; Rajput, P.; Mandzhieva, S.; Alexiou, A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles influence on plant tolerance to salinity stress: Insights into physiological, biochemical, and molecular responses. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulraheem, M.I.; Xiong, Y.; Moshood, A.Y.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J. Mechanisms of Plant Epigenetic Regulation in Response to Plant Stress: Recent Discoveries and Implications. Plants 2024, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Rani, K. Epigenomics in stress tolerance of plants under the climate change. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6201–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Z.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y. Epigenetics in Plant Response to Climate Change. Biology 2025, 14, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, H.A.; Hassan, M.U.; Zain, M.; Irshad, A.; Shakoor, N.; Saleem, S.; Niu, J.; Skalicky, M.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Z.; et al. Nanosized zinc oxide (n-ZnO) particles pretreatment to alfalfa seedlings alleviate heat-induced morpho-physiological and ultrastructural damages. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faseela, P.; Sinisha, A.K.; Brestič, M.; Puthur, J.T. Chlorophyll a fluorescence parameters as indicators of a particular abiotic stress in rice. Photosynthetica 2020, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wei, R.; Liang, Y.; Zuo, L.; Huo, M.; Huang, Z.; Lang, J.; Zhao, X.; et al. Impact of Abiotic Stress on Rice and the Role of DNA Methylation in Stress Response Mechanisms. Plants 2024, 13, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Chachar, M.; Ali, A.; Chachar, Z.; Zhang, P.; Riaz, A.; Ahmed, N.; Chachar, S. Epigenetic Regulation for Heat Stress Adaptation in Plants: New Horizons for Crop Improvement under Climate Change. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving abiotic stress tolerance in plants through antioxidative defense mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, V.D.; Harish; Singh, R.K.; Verma, K.K.; Sharma, L.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Meena, M.; Gour, V.S.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; et al. Recent Developments in Enzymatic Antioxidant Defence Mechanism in Plants with Special Reference to Abiotic Stress. Biology 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xia, Y.; Song, K.; Liu, D. The Impact of Nanomaterials on Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Mechanisms in Gramineae Plants: Research Progress and Future Prospects. Plants 2024, 13, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Andrews, J.; Fugice, J.; Singh, U.; Bindraban, P.S.; Elmer, W.H.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.; White, J.C. Facile coating of urea with low-dose ZnO nanoparticles promotes wheat performance and enhances Zn uptake under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Bindraban, P.S. Nanofertilizers: New products for the industry? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 66, 6462–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, C.M.; Majumdar, S.; Duarte-Gardea, M.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Interaction of nanoparticles with edible plants and their possible implications in the food chain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Pandey, R.; Singh, V.P.; Sharma, N.C.; Prasad, S.M.; Dubey, N.K.; Chauhan, D.K. An overview on manufactured nanoparticles in plants: Uptake, translocation, accumulation and phytotoxicity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Geiser-Lee, J.; Deng, Y.; Kolmakov, A. Interactions between engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) and plants: Phytotoxicity, uptake and accumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3053–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, K.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Q.; Dun, C.; Wang, R.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H. Zinc oxide nanoparticles enhanced rice yield, quality, and zinc content of edible grain fraction synergistically. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1196201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hui, W.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; He, G. Absorption and transport of different ZnO nanoparticles sizes in Agrostis stolonifera: Impacts on physiological, biochemical responses, root exudation, and microbial community structure. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 219, 109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Naik, I.S.; Das, B.; Singh, A.; Nayak, P.; Mohapatra, C.; Debnath, D.; Tripathy, M.; Behera, K.; Masika, F.B.; et al. Nanoparticles in plant system: A comprehensive review on their role in diverse stress management and phytohormone signaling. Plant Stress 2025, 18, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Yousaf, B.; Ali, M.U.; Munir, M.A.M.; El-Naggar, A.; Rinklebe, J.; Naushad, M. Transformation pathways and fate of engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) in distinct interactive environmental compartments: A review. Environ. Int. 2020, 138, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwal, M.K.; Kumar, R.; Prakash, K.; Rai, G.K.; Hebbar, K.B. Antioxidant defense system in plants against abiotic stress. In Abiotic Stress Tolerance Mechanisms in Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Signaling, and Scavenging During Abiotic Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bharati, R.; Kubes, J.; Popelkova, D.; Praus, L.; Yang, X.; Severova, L.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles application alleviates salinity stress by modulating plant growth, biochemical attributes and nutrient homeostasis in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1432258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshoky, H.A.; Yotsova, E.; Farghali, M.A.; Farroh, K.Y.; El-Sayed, K.; Elzorkany, H.E.; Rashkov, G.; Dobrikova, A.; Borisova, P.; Stefanov, M.; et al. Impact of foliar aerosol of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the photosynthesis of Pisum sativum L. under salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Ahmad, A.; Alhammad, B.A.; Tola, E. Exogenous Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Improved Antioxidants, Photosynthetic, and Yield Traits in Salt-Stressed Maize. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, F.; Asadi, M.; Hassanpouraghdam, M.B.; Aazami, M.A.; Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Kakaei, K.; Dokoupil, L.; Mlcek, J. Foliar Application of ZnO-NPs Influences Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Antioxidants Pool in Capsicum annum L. under Salinity. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarin, K.; Usatov, A.; Minkina, T.; Duplii, N.; Kasyanova, A.; Fedorenko, A.; Khachumov, V.; Mandzhieva, S.; Rajput, V.D. Effects of bulk and nano-ZnO particles on functioning of photosynthetic apparatus in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M.; Sathish, M.; Kiran, R.; Mushtaq, A.; Baazeem, A.; Hasnain, A.; Hakim, F.; Hassan Naqvi, S.A.; Mubeen, M.; Iftikhar, Y.; et al. Plant Nitrogen Metabolism: Balancing Resilience to Nutritional Stress and Abiotic Challenges. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Dias, M.C.; Silva, A.M.S. Titanium and Zinc Based Nanomaterials in Agriculture: A Promising Approach to Deal with (A)biotic Stresses? Toxics 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Sadhukhan, A. Molecular mechanisms of plant productivity enhancement by nano fertilizers for sustainable agriculture. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 114, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.K.; Fahad, S.; Kumar, P.; Choyal, P.; Javed, T.; Jinger, D.; Singh, P.; Saha, D.; MD, P.; Bose, B.; et al. Beneficial elements: New Players in improving nutrient use efficiency and abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.; Singh, M.; Pandey-Rai, S. Crosstalk of nanoparticles and phytohormones regulate plant growth and metabolism under abiotic and biotic stress. Plant Stress 2022, 6, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, A.; Safdar, N.; Ain, N.U.; Yasmin, A.; Chaudhry, G.E.S. Abscisic acid-loaded ZnO nanoparticles as drought tolerance inducers in Zea mays L. with physiological and biochemical attributes. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 7280–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, F. The impact of nanoparticles on plant growth, development, and stress tolerance through regulating phytohormones. In Nanoparticles in Plant Biotic Stress Management; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankova, R.; Landa, P.; Podlipna, R.; Dobrev, P.I.; Prerostova, S.; Langhansova, L.; Gaudinova, A.; Motkova, K.; Knirsch, V.; Vanek, T. ZnO nanoparticle effects on hormonal pools in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 593, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, H.E. Green Synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles Improve the Growth and Phytohormones Biosynthesis and Modulate the Expression of Resistance Genes in Phaseolus vulgaris. Egypt. J. Bot. 2024, 64, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, S.; Sharma, L.; Singh, R.K.; Pandey, B.; Rathore, S.S.; Singh, A.K.; Porwal, P.; Singh, S.P. Plant stress hormones nanobiotechnology. In Nanobiotechnology: Mitigation of Abiotic Stress in Plants; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, B.J.; Noor, A.; Zulfiqar, A.; Zeenat, A.; Ahmad, S.; Chishti, I.; Abbas, Z.; Shakeel, S.N. Effect of ZnO, SiO2 and composite nanoparticles on Arabidopsis thaliana and involvement of ethylene and cytokinin signaling pathways. Pak. J. Bot. 2021, 53, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Ju, Q.; Xu, J. Physiological, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analyses reveal zinc oxide nanoparticles modulate plant growth in tomato. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 3587–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail; Sawati, L.; Ferrari, E.; Stierhof, Y.D.; Kemmerling, B.; Mashwani, Z.U.R. Molecular effects of biogenic zinc nanoparticles on the growth and development of Brassica napus L. revealed by proteomics and transcriptomics. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 798751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Mohamed, G.F.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Abd El-Mageed, S.A.; Rady, M.M.; Ali, E.F. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles promotes drought stress tolerance in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plants 2021, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zohri, M.; Al-Wadaani, N.A.; Bafeel, S.O. Foliar sprayed green zinc oxide nanoparticles mitigate drought-induced oxidative stress in tomato. Plants 2021, 10, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M.I.; Saleem, S.; Rather, S.A.; Rehmani, M.S.; Alamri, S.; Rajput, V.D.; Kalaji, H.M.; Saleem, N.; Sial, T.A.; Liu, M. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An effective strategy to mitigate drought stress in cucumber seedling by modulating antioxidant defense system and osmolytes accumulation. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, A.; Haidri, I.; Shafqat, U.; Khan, I.; Iqbal, M.; Mahmood, F.; Hassan, M.U. Impact of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles on physiological and biochemical attributes of pea (Pisum sativum L.) under drought stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2025, 31, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, T.R.; Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, M.M.; Keya, S.S.; Van Ha, C.; Khan, M.A.R.; Abdelrahman, M.; Dao, M.N.K.; Chu, H.D.; Tran, L.S.P. Comparative effects of ZnSO4 and ZnO-NPs in improving cotton growth and yield under drought stress at early reproductive stage. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, T.; Safdar, A.; Qureshi, H.; Siddiqi, E.H.; Ullah, N.; Naseem, M.T.; Soufan, W. Synergistic effects of Vachellia nilotica-derived zinc oxide nanoparticles and melatonin on drought tolerance in Fragaria × ananassa. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghaninia, M.; Mashhouri, S.M.; Najafifar, A.; Soleimani, F.; Wu, Q.S. Combined effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on soybean yield, oil quality, and biochemical responses under drought stress. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimović, A.; Arsenov, D.; Borišev, M.; Djordjević, A.; Župunski, M.; Borišev, I. Foliar application of fullerenol and zinc oxide nanoparticles improves stress resilience in drought-sensitive Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0330022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroutan, L.; Solouki, M.; Abdossi, V.; Fakheri, B.A.; Mahdinezhad, N.; Gholamipourfard, K.; Safarzaei, A. The effects of Zinc oxide nanoparticles on drought stress in Moringa peregrina populations. Int. J. Basic Sci. Med. 2019, 4, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel Deger, A.; Çevik, S.; Kahraman, O.; Turunc, E.; Yakin, A.; Binzet, R. Effects of green and chemically synthesized ZnO nanoparticles on Capsicum annuum under drought stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2025, 47, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, A.R.; Mahdi, A.A.; Farroh, K.Y. Improving drought stress tolerance in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) using magnetite and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2022, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamze, H.; Khalili, M.; Mir-Shafiee, Z.; Nasiri, J. Integrated biomarker response version 2 (IBRv2)-Assisted examination to scrutinize foliar application of jasmonic acid (JA) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) toward mitigating drought stress in sugar beet. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, R.; Ahmed, M.; Abdul-Hamid, D.; Zedan, M.; Tóth, Z.; Decsi, K. Resulting Key Physiological Changes in Triticum aestivum L. Plants Under Drought Conditions After Priming the Seeds with Conventional Fertilizer and Greenly Synthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles from Corn Wastes. Agronomy 2025, 15, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathirvelan, P.; Vaishnavi, S.; Manivannan, V.; Djanaguiraman, M.; Thiyageshwari, S.; Parasuraman, P.; Kalarani, M.K. Response of Maize (Zea mays L.) to Foliar-Applied Nanoparticles of Zinc Oxide and Manganese Oxide Under Drought Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, A.; Javad, S.; Naseer, I.; Alam, P.; Almutairi, Z.M.; Faizan, M.; Zauq, S.; Shah, A.A. Efficacy of chitosan loaded zinc oxide nanoparticles in alleviating the drastic effects of drought from corn crop. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Fatima, M.; Fatima, T.; Sarfraz, A.; Qureshi, H.; Anwar, T.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Ismoilov, I.; Tukhtaboeva, F.; Rebouh, N.Y.; et al. Enhancing drought tolerance in wheat using zinc and iron nanoparticles: Implications for sustainable industrial crop productivity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 236, 121876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, S.M.; El-Bakatoushi, R.F.; Amin, A.W.; El-Sadek, L.M.; Migahid, M.M. Nanopriming as an approach to induce tolerance against drought stress in wheat cultivars. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 2343–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shazoly, R.M.; Othman, A.A.; Zaheer, M.S.; Al-Hossainy, A.F.; Abdel-Wahab, D.A. Zinc oxide seed priming enhances drought tolerance in wheat seedlings by improving antioxidant activity and osmoprotection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanif, S.; Farooq, S.; Kiani, M.Z.; Zia, M. Surface modified ZnO NPs by betaine and proline build up tomato plants against drought stress and increase fruit nutritional quality. Chemosphere 2024, 362, 142671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, Y.; Alam, P.; Sultan, H.; Sharma, R.; Soysal, S.; Baran, M.F.; Faizan, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles for sustainable agriculture: A tool to combat salinity stress in rice (Oryza sativa) by modulating the nutritional profile and redox homeostasis mechanisms. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elzaher, M.A.; El-Desoky, M.A.; Khalil, F.A.; Eissa, M.A.; Amin, A.E.E.A. Exogenously applied proline with silicon and zinc nanoparticles to mitigate salt stress in wheat plants grown on saline soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1559–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Khan Sehrish, A.; Hussain, A.; Zhang, L.; Owdah Alomrani, S.; Ahmad, A.; Al Ghanim, K.A.; Alshehri, M.S.; Ali, S.; Sarker, P.K. Salt stress amelioration and nutrient strengthening in spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) via biochar amendment and zinc fortification: Seed priming versus foliar application. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozaba, T.O.; Kuru, İ.S. The effect of the combined application of elicitors to Salvia virgata Jacq. under salinity stress on physiological and antioxidant defense. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherpa, D.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, S. Response of different doses of zinc oxide nanoparticles in early growth of mung bean seedlings to seed priming under salinity stress condition. Legume Res.-Int. J. 2024, 1, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Yadav, S.K.; Choudhary, R.; Rao, D.; Sushma, M.K.; Mandal, A.; Hussain, Z.; Minkina, T.; Rajput, V.D.; Yadav, S. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticle based seed priming for enhancing seed vigour and physio-biochemical quality of tomato seedlings under salinity stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 71, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdallah, N.M. Salt stress mitigation in chickpea seedlings: A comparative study of zinc oxide nano and bulk particles. Plant Soil Environ. 2025, 71, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Mahmood, F.; Zhao, Z.; Khaliq, H.; Usman, M.; Muhammad, T.; Ashraf, G.A. Effect of the foliar application of biogenic-ZnO nanoparticles on physio-chemical analysis of chilli (Capsicum annum L.) in a salt stress environment. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.A.; Khan, A.; Irfan, M. Role of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Alleviating Sodium Chloride-Induced Salt Stress in Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 188–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahawar, L.; Živčák, M.; Barboricova, M.; Kovár, M.; Filaček, A.; Ferencova, J.; Visoká, D.M.; Brestič, M. Effect of copper oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles on photosynthesis and physiology of Raphanus sativus L. under salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türkoğlu, A.; Haliloğlu, K.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Yildirim, E.; Öztürk, H.İ.; Stansluos, A.A.L.; Nadaroğlu, H.; Piekutowska, M.; Niedbała, G. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: An Influential Element in Alleviating Salt Stress in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa L. Cv Atlas). Agronomy 2024, 14, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Shan, R.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, L.; Song, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J.; Jiang, M. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Alleviate Salt Stress in Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) by Adjusting Na+/K+ Ratio and Antioxidative Ability. Life 2024, 14, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez-Mori, J.B.; Lapiz-Culqui, Y.K.; Huaman-Huaman, E.; Zuta-Puscan, M.; Oliva-Cruz, M. Can Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Alleviate the Adverse Effects of Salinity Stress in Coffea arabica? Agronomy 2025, 15, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Marrez, D.A.; Rizk, R.; Abdul-Hamid, D.; Tóth, Z.; Decsi, K. Interventional Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles with Zea mays L. Plants When Compensating Irrigation Using Saline Water. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, H.; Bai, J.; Cheng, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, Y.; Shao, X. Impact of ZnO NPs on photosynthesis in rice leaves plants grown in saline-sodic soil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Munir, N.; Abideen, Z.; Yong, J.W.H.; El-Keblawy, A.; El-Sheikh, M.A. Synthesis and optimization of nanoparticles from Phragmites karka improves tomato growth and salinity resilience. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 55, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, A.; Pitann, B.; Hossain, M.S.; Saqib, Z.A.; Nawaz, A.; Mühling, K.H. Zinc and silicon fertilizers in conventional and nano-forms: Mitigating salinity effects in maize (Zea mays L.). J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2024, 187, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, F.; Hou, X.; Xing, B. Zinc oxide nanoparticles cooperate with the phyllosphere to promote grain yield and nutritional quality of rice under heatwave stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2414822121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthelezi, D. Lessertia frutescens L. Leaf Extract Enriched with Biosynthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Enhances the Growth, Essential Oil and Antioxidant Activities of Origanum vulgare L. Under Heat Stress. In Proceedings of the Plants 2025: From Seeds to Food Security, Barcelona, Spain, 31 March–2 April 2025; Available online: https://sciforum.net/paper/view/21828 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Wu, J.; Wang, T. Synergistic effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles and heat stress on the alleviation of transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 104, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Zeng, H.; Zhou, Q. Heatwave enhance the adaptability of Chlorella pyrenoidosa to zinc oxide nanoparticles: Regulation of interfacial interactions and metabolic mechanisms. Water Res. 2025, 279, 123466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.A.; Safwat, G.; Eliwa, N.E.; Eltawil, A.H.; Abd El-Aziz, M.H. Changes in morphological traits, anatomical and molecular alterations caused by gamma-rays and zinc oxide nanoparticles in spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) plant. BioMetals 2023, 36, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safshekan, S.; Pourakbar, L.; Rahmani, F. The effect of Zn NPs on some growth, biochemical and anatomical factors of Chickpea plant stem under UVB irradiation. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 12, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Mao, F.; Bai, J. Effect of Different Concentrations of Exogenous ZnONPs on the Heat Tolerance of Snapdragon. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2024, 53, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.S.; Salah El Din, T.A.; Hendawey, M.H.; Borai, I.H.; Mahdi, A.A. Magnetite and zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviated heat stress in wheat plants. Curr. Nanomater. 2018, 3, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, A.; Tanveer, Y.; Yasmin, H.; Hassan, M.N.; Shahzad, A.; Reddy, M.; Ahmad, A. Coactive role of zinc oxide nanoparticles and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for mitigation of synchronized effects of heat and drought stress in wheat plants. Chemosphere 2022, 297, 133982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidri, I.; Ishfaq, A.; Shahid, M.; Hussain, S.; Shahzad, T.; Shafqat, U.; Mustafa, S.; Mahmood, F. Enhancement of antioxidants’ enzymatic activity in the wheat crop by Shewanela sp. mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles against heavy metals contaminated wastewater. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 7068–7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hao, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, D. Comparative physiological and transcriptomic analyses reveal enhanced mitigation of cadmium stress in peanut by combined Fe3O4/ZnO nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Kaousar, R.; Haq, S.I.U.; Shan, C.; Wang, G.; Rafique, N.; Shizhou, W.; Lan, Y. Zinc-oxide nanoparticles ameliorated the phytotoxic hazards of cadmium toxicity in maize plants by regulating primary metabolites and antioxidants activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1346427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Bhatti, K.H.; Rashid, A.; Hussain, K.; Nawaz, K.; Fatima, N.; Hanif, A. Alleviation of heavy metal toxicity (arsenic and chromium) from morphological, biochemical and antioxidant enzyme assay of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using zinc-oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPS). Pak. J. Bot 2024, 56, 2129–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zada, S.; Khan, N.; Hu, Z.; Tang, Y. Discovering Nature’s shield: Metabolomic insights into green zinc oxide nanoparticles Safeguarding Brassica parachinensis L. from cadmium stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Han, M.; Yan, X. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviate cadmium toxicity and promote tolerance by modulating programmed cell death in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, O.; Dimkpa, C.O.; Chaoui, A.; Kouki, A.; Amara, A.B.H.; Karmous, I. Zinc oxide nanoparticles at low dose mitigate lead toxicity in pea (Pisum sativum L.) seeds during germination by modulating metabolic and cellular defense systems. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.A.; Zafar, S.; Usman, S.; Javad, S.; Aslam, M.; Noreen, Z.; Elansary, H.O.; Almutari, K.F.; Ahmad, A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and Klebsiella sp. SBP-8 alleviates chromium toxicity in Brassica juncea by regulation of antioxidant capacity, osmolyte production, nutritional content and reduction in chromium adsorption. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H.; Yasmeen, F.; Hanif, A.; Siddiqi, E.H.; Anwaar, S.; Gul, S.; Ashraf, T.; Okla, M.K.; Adil, M.F. Amelioration of cadmium stress by supplementation of melatonin and ZnO-nanoparticles through physiochemical adjustments in Brassica oleracea var. capitata. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Raja, V.; Bhat, A.H.; Kumar, N.; Alsahli, A.A.; Ahmad, P. Innovative strategies for alleviating chromium toxicity in tomato plants using melatonin functionalized zinc oxide nanoparticles. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 341, 113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahirad, S.; Dadpour, M.; Gohari, G.; Fotopoulos, V. Simultaneous application of titanium dioxide (TiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles ameliorates lead (Pb) stress effects in medicinal plant Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench. Plant Stress 2024, 13, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, T.; Du, Q.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, X.; Tang, Z. Foliar nanoparticles alleviated cadmium-induced phytotoxicity in dandelion via regulation of ionomics, metabolomics, and rhizobacterial networks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandali, M.V.; Safarzadeh, S.; Ghasemi-Fasaei, R.; Zeinali, S. Heavy metals immobilization and bioavailability in multi-metal contaminated soil under ryegrass cultivation as affected by ZnO and MnO2 nanoparticle-modified biochar. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppa, E.; Quagliata, G.; Palombieri, S.; Iavarone, C.; Sestili, F.; Del Buono, D.; Astolfi, S. Biogenic ZnO Nanoparticles Effectively Alleviate Cadmium-Induced Stress in Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Plants. Environments 2024, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Sharma, N.L.; Singh, D.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Sarkar, S.K.; Rathore, A.; Prasad, S.K.; Gaafar, A.-R.Z.; Hussain, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviate chromium-induced oxidative stress by modulating physio-biochemical aspects and organic acids in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrish, A.K.; Ahmad, S.; Nafees, M.; Mahmood, Z.; Ali, S.; Du, W.; Naeem, M.K.; Guo, H. Alleviated cadmium toxicity in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by the coactive role of zinc oxide nanoparticles and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on TaEIL1 gene expression, biochemical and physiological changes. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hernández, H.; Pérez-Moreno, A.Y.; Méndez-López, A.; Fernández-Luqueño, F. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles during the process of phytoremediation of soil contaminated with As and Pb cultivated with sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahira, S.; Bahadur, S.; Lu, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. ZnONPs alleviate cadmium toxicity in pepper by reducing oxidative damage. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R.; Shafiq, M.; Batool, A.; Din, M.I.; Sami, A. Investigate the impact of zinc oxide nanoparticles under lead toxicity on Chilli (Capsicum annuum L). Bull. Biol. Allied Sci. Res. 2024, 2024, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, R.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Siddique, K.H.; Mao, H. Enhancing zinc biofortification and mitigating cadmium toxicity in soil–earthworm–spinach systems using different zinc sources. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Zivcak, M.; Sytar, O.; Kalaji, H.M.; He, X.; Mbarki, S.; Brestic, M. Impact of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles on plants: A critical review. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari Yaichi, Z.; Hassanpouraghdam, M.B.; Rasouli, F.; Aazami, M.A.; Vojodi Mehrabani, L.; Jabbari, S.F.; Asadi, M.; Esfandiari, E.; Jimenez-Becker, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles foliar use and arbuscular mycorrhiza inoculation retrieved salinity tolerance in Dracocephalum moldavica L. by modulating growth responses and essential oil constituents. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, V.; Singh, K.; Qadir, S.U.; Singh, J.; Kim, K.H. Alleviation of cadmium-induced oxidative damage through application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and strigolactones in Solanum lycopersicum L. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 2633–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Kareem, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Guo, Z.; Niu, J.; Roy, M.; Saleem, S.; Wang, Q. Enhanced salinity tolerance in Alfalfa through foliar nano-zinc oxide application: Mechanistic insights and potential agricultural applications. Rhizosphere 2023, 28, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Ascorbate and glutathione: The heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abiotic Stress | Nanoparticles | Crop | Type of Application and Doses | Response Under the Effect of NPs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought stress (60% ETc) and salinity (saline soil) | ZnO-NPs | Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) | 0, 50, 100 ppm (foliar spray) | Increased relative water content, membrane stability, photosynthetic efficiency, growth, yield (12–23%), and water productivity (51–66%). | [95] |

| Drought (100, 75, 50, 25% field capacity) | Green ZnO-NPs | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) | 25, 50, 100 mg L−1 (foliar spray) | Improved shoot and root biomass; 25–50 mg/L increased shoot dry weight 2–2.5-fold under severe drought; reduced malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide; enhanced antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX up to 4.6-, 3.6-, and 3.3-fold higher); 100 mg/L increased oxidative stress. | [96] |

| Drought (40% field moisture capacity) vs. non-drought (80% FMC) | Zinc-NPs (urea-coated 1%) vs. bulk ZnO (2%) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | ≤2.17 mg kg−1 ZnO-NPs, ≤4.34 mg kg−1 bulk ZnO | Under drought, ZnO-NPs reduced panicle initiation by 5 days, increased grain yield by 39–51%, and improved Zn uptake by 24%. Bulk ZnO had no significant effect on yield. Nanoparticles achieved higher efficiency with lower Zn input. | [66] |

| Drought (50% field capacity) | ZnO-NPs | Moringa (Moringa peregrina) | 0.05% and 0.1% (foliar aerosol) | Prevented chlorophyll degradation, increased chlorophyll content in well-watered plants, enhanced total phenolic content, and antioxidant activity under both drought and non-drought conditions. | [103] |

| Drought stress (withholding irrigation for 7 days) | Green synthesized and commercial ZnO-NPs | Chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) | 0, 500, 1000 mg L−1 (foliar application) | Drought reduced relative water content and leaf water potential while increasing proline, TBARS, and antioxidant enzymes. ZnO-NPs improved water status and reduced oxidative markers; green-synthesized ZnO-NPs (100–500 mg/L) were more effective than chemically synthesized ones in mitigating the effects of drought. | [104] |

| Drought stress (induced with sorbitol 0.0–0.4 M) | (ZnO-NPs) and magnetite nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NPs) | Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) | 0.0, 2.5, 5.0 mg mL−1 | Sorbitol ≥ 0.3 M reduced growth and stopped at 0.4 M. ZnO-NPs (2.5–5.0 mg mL−1) and Fe3O4-NPs (2.5–5.0 mg mL−1) improved micropropagation, microtuberization, and biochemical traits under drought. Almond cultivar showed higher quercetin, kaempferol, and DPPH activity, especially at ZnO-NPs (5.0 mg mL−1) and Fe3O4-NPs (2.5–5.0 mg mL−1). | [105] |

| Drought stress (pot experiment) | ZnO-NPs | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) | 25, 100 mg L−1 (foliar application) | Improved growth and biomass under drought; enhanced photosynthetic pigments, photosynthesis, and PSII activity (maximal at 100 mg L−1); reduced ROS and lipid peroxidation; increased enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants; elevated proline, glycine betaine, amino acids, and sugars; mitigated drought-induced decline in phenols and mineral nutrients. | [97] |

| Drought stress (60% field capacity, FC) | ZnO-NPs | Pea (Pisum sativum L.) common | 50 ppm (seed priming), 100 ppm (foliar), 150 ppm (soil drenching) | Seed priming (50 ppm) enhanced growth, physiology, antioxidant levels, and mineral content by 35–57%. Foliar (100 ppm) enhanced by 43–64%. Soil drenching (150 ppm) improved by 47–64%. All treatments reduced osmotic stress and boosted drought resilience. | [98] |

| Drought stress (withholding) irrigation for 6 days at the first square stage) | ZnO-NPs vs. zinc sulfate (ZnSO4·7H2O) | Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) | ZnO-NPs: 0.1 g Kg−1 potting mix; ZnSO4·7H2O: 1.0 g Kg−1 potting mix | ZnO-NPs improved growth, root and shoot biomass, hydration status, antioxidant enzyme activity, membrane integrity, and mineral uptake compared to ZnSO4. ZnO-NPs also enhanced yield and fiber quality under drought and well-watered conditions. | [99] |

| Drought stress (optimal irrigation = 20% depletion, moderate deficit = 50% depletion, severe deficit = 80% depletion) | ZnO-NPs alone or combined with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) | Soybean (Glycine max L.) | ZnO-NPs: 200 mg L−1 (foliar); AMF: proprietary blend; combined ZnO-NPs + AMF | Combined ZnO-NPs + AMF enhanced root colonization, nutrient uptake (N, P, K, Zn), proline, soluble carbohydrates, and antioxidant enzymes; reduced oxidative markers. Increased yield (+145%) and oil content (+24%), improved oil composition (higher linoleic and linolenic acids, lower palmitic and stearic acids), and oil quality indices. | [101] |

| Drought stress (100% irrigation requirement = control, 75% irrigation requirement = moderate stress, 50% irrigation requirement = severe stress) | ZnO-NPs compared with jasmonic acid (JA) | Sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) | ZnO-NPs: 0.2 mL L−1 (foliar); JA: 100 µM (foliar) | ZnO-NPs increased sugar content, beta-glycine, and antioxidant enzyme activity under drought. JA at 50% irrigation had a slightly more substantial moderating effect than ZnO-NPs. Both treatments improved root yield, antioxidant defense, and growth under water stress. | [106] |

| Drought stress (50% of the required moisture at the vegetative stage, maintained at 60% field capacity) | ZnO-NPs combined with melatonin (MT) | Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch) | ZnO-NPs: 0.5 g L−1; MT: 0.1 g L−1 (foliar, alone or combined) | Combined ZnO-NPs + MT improved shoot and root length, fruit biomass, bud formation, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, POD, CAT), while reducing H2O2 and MDA levels under drought conditions. The combined treatment outperformed ZnO-NPs or MT alone in enhancing growth and stress tolerance. | [100] |

| Drought stress (irrigation withheld for 8 days until soil moisture reached 8–10% vol) | ZnO-NPs alone, fullerenol nanoparticles (FNPs), and combined ZnO + FNPs | Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana L.) | ZnO-NPs: 10 mg L−1 (foliar); FNPs: micromolar concentrations (foliar); combined ZnO + FNPs | ZnO-NPs (10 mg L−1) improved drought acclimation; FNPs optimized photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, and water-use efficiency due to antioxidative and hygroscopic properties; both reduced ROS, stabilized redox balance, and enhanced antioxidant enzymes. Combined ZnO + FNPs showed synergistic protective effects and modulated ABA-dependent and independent drought-response genes. | [102] |

| Drought stress (50% pot capacity, applied 30 days after sowing, compared with 100% PC control) | ZnO-NPs synthesized from corn husks | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Seed priming with ZnO-NPs (200 mg L−1) or DR GREEN fertilizer (40 g L−1) | ZnO-NP priming enhanced activity of antioxidant enzymes (POX, CAT, GR), increased total phenolics, flavonoids, and sugars; alleviated oxidative stress under drought but also showed potential phytotoxic risks; overall improved stress resilience compared to conventional nutri-priming. | [107] |

| Drought stress (withholding irrigation from tasseling to grain filling for 21 days) | ZnO-NPs, 100 mg L−1), manganese oxide nanoparticles (MnO-NPs, 20 mg L−1), ZnO-NPs + MnO-NPs, TNAU Nano Revive (1.0%), ZnSO4 0.25% + MnSO4 0.25% | Maize (Zea mays L.) | Foliar application of ZnO-NPs (100 mg L−1) and MnO-NPs (20 mg L−1), alone or in combination | ZnO-NPs and MnO-NPs reduced the anthesis–silking interval, improved chlorophyll index, proline, and green leaf area under drought. Combined ZnO-NPs + MnO-NPs enhanced seed-filling rate (+90%), duration (+13%), and seed yield (+52%) compared with the control. | [108] |

| Drought stress induced with 20% PEG solution (15 days) | Chitosan-loaded ZnO-NPs synthesized with Nigella sativa | Maize (Zea mays L.) | Foliar spray with CSNPs ranging from 300 µg L−1 to 500 mg L−1 | Chitosan-loaded ZnO-NPs mitigated drought stress by enhancing growth traits (plant length +10.2%, leaf area +29.9%, ear length +8.7%, cob weight +47.2%, grains +462.4%). Improved osmotic potential, relative water content, and membrane stability index. Reduced oxidative stress markers (MDA −21.1%, proline −5.5%) while increasing proteins (+61.7%), flavonoids (+21.1%), and antioxidant enzymes (CAT +13.7%, POD +27.2%, SOD +24.7%). | [109] |

| Drought stress induced with 20% PEG-6000 (hydroponics) and irrigation withholding (pot experiment) | ZnO-NPs, at 60 ppm; Iron oxide nanoparticles (FeO-NPs) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L., cultivars Johar-16, Faisalabad-08, Aas) | Foliar/nutrient solution application of ZnO-NPs (60 ppm) and FeO-NPs (dose not specified beyond ~58 nm characterization) | Drought reduced shoot length, RWC, and increased proline. ZnO-NPs (60 ppm) restored shoot length (up to 66.7 cm in Johar-16), RWC (88.4%), and improved root biomass. FeO-NPs enhanced shoot dry weight (9.73 g) and grain yield (+74% in Faisalabad-08). Johar-16 showed the best physiological adjustment, Faisalabad-08 showed the best yield resilience, and Aas showed moderate responses. ZnO-NPs were more effective for growth recovery, and FeO-NPs for yield enhancement. | [110] |

| Drought stress induced by different field capacities (80, 60, 40, and 20%) Drought stress induced by different field capacities (80, 60, 40, and 20%) | ZnO-NPs used for seed priming (nanopriming) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Hydropriming; ZnO-NPs at 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 g/L | Hydropriming and nanopriming alleviated drought effects, improving relative water content, leaf area, and root traits. Specific root length increased under drought but was reduced by priming, indicating that stress was alleviated. ZnO-NPs increased osmolytes (proteins, proline, soluble sugars), antioxidants (DPPH activity, phenolics), and induced a stress-resistant protein band at 40% field capacity. Nanopriming modulated protein synthesis/metabolism, enhancing drought tolerance in both cultivars. | [111] |

| Drought stress at 80% and 60% field capacity (FC) | ZnO-NPs (nanopriming) and bulk ZnO seed priming | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings | 60 mg L−1 (ZnO-NPs and bulk ZnO for seed priming) | Both ZnO-NPs and bulk ZnO priming mitigated drought stress effects, especially at 60% FC. Enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities (POD ↑ 91.8–289.9% shoots, 218.6–261.6% roots), phenolics ↑ 194.4% shoots and 1139.6% roots, H2O2 scavenging ↑ 124.9–147.6%, lipid peroxidation inhibition ↑ 320.6–433%. Increased free amino acids (↑ 393.8–502.8% roots) and soluble carbohydrates (↑ 183.4% roots). Results confirmed adequate biochemical and physiological protection. | [112] |

| Drought stress (greenhouse; control = irrigation every 3 days; drought = irrigation withheld until wilting) | ZnO-NPs; Proline-primed ZnO (ZnOP); Betaine-primed ZnO (ZnOBt) | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Soil application: 50 and 100 mg kg−1 (mixed with 2.5 kg soil per pot) | Increased plant height (ZnOP50: 1.09 m; ZnO100: 1.06 m); improved chlorophyll content (ZnOP: +86%, ZnOBt: +87.16%); maximum yield with ZnOP (204 g/g/plant); reduced oxidative stress (lower phenolics/flavonoids in stressed leaves); enhanced fruit nutritional quality (↑ phenolics, flavonoids, lycopene, betaine, and proline). | [113] |

| Abiotic Stress | Nanoparticles | Crop | Type of Application and Doses | Response Under the Effect of NPs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salt stress (200 mM NaCl) | ZnO-NPs | Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) | 25, 50, 100, 200 mg L−1 (foliar spray, seed nanopriming, soil application) | ZnO-NPs alleviated salinity stress by enhancing plant growth traits, including fresh weight (+24%), relative water content (+27%), plant height (+33%), and chlorophyll content (+37%). Stress markers such as proline (↑ >100%), Na+ accumulation, and ROS levels were significantly reduced. Antioxidant enzyme activities improved, supporting redox balance and membrane stability. Among the application methods, nanopriming was the most effective, restoring growth and physiological traits to near control levels. | [77] |

| Salt stress (50 mM and 100 mM NaCl) | ZnO-NPs | Pea (Pisum sativum L.) | Foliar application of ZnO-NPs at 50 and 100 ppm (applied individually and with NaCl) | ZnO-NPs at 50 ppm alone improved growth traits (root length ↑, other growth parameters ↑) and reduced oxidative damage (MDA ↓, H2O2 ↓). High salt concentrations (50–100 mM NaCl) alone decreased all parameters. The best combined treatment was 50 ppm ZnO-NPs + 50 mM NaCl, which significantly improved root length, physiological traits, and lowered MDA, glycine betaine, and H2O2. | [20] |

| Salt stress (150 mM NaCl, applied at 15 DAS) | ZnO-NPs | Rice (Oryza sativa L.) | Foliar spray of ZnO-NPs at 100 mg L−1 for five consecutive days (26–30 DAS) | ZnO-NPs significantly improved shoot and root growth, photosynthetic pigments (SPAD ↑ 29%), and photosynthesis (net rate ↑ 24%). Enhanced nutrient uptake (N, P, K, Zn ↑ 9–17%) and boosted antioxidant enzyme activities. ZnO-NPs reduced oxidative damage by lowering H2O2 and MDA contents, and mitigated salinity-induced proline over-accumulation. Overall, ZnO-NPs promoted growth recovery and enhanced stress tolerance under severe salt stress. | [114] |

| Salt stress (0, 150, and 300 mM NaCl) | ZnO-NPs and copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) | Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) | Foliar spray at 100 mg L−1 for 15 days on 15-day-old seedlings | Salinity reduced nutrient uptake, leaf area, and photosynthetic efficiency, while increasing proline, anthocyanin, and flavonoid levels, as well as antioxidant enzyme activities. Foliar application of ZnO-NPs significantly alleviated these effects by improving leaf area, mineral content, photosynthetic electron transport rate, PSII quantum yield, and stomatal conductance. ZnO-NPs also reduced oxidative stress by lowering proline, anthocyanin, and flavonoid levels, as well as enzymatic activities (SOD, APX, and GOPX). ZnO-NPs were more effective than CuO-NPs in enhancing growth and mitigating salt-induced damage. | [123] |

| Salt stress (0, 100, 200 mM NaCl) | Green-synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and bulk Zn | Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa L.) | Foliar application at 0, 50, 100, and 200 ppm | Salinity stress reduced plant growth (height, weight, diameter), chlorophyll content, and altered ion ratios (K/Na and Ca/Na), while increasing oxidative stress markers (H2O2 and MDA) and osmolytes (proline and sucrose). The application of ZnO-NPs mitigated these effects by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, POD), reducing oxidative damage, stabilizing ion homeostasis, and improving chlorophyll content and plant growth. ZnO-NPs were more effective than bulk Zn in promoting stress tolerance and physiological recovery. | [124] |

| Salt stress (field conditions, saline soil—exact NaCl level not specified) | ZnO NPs, SiO2 NPs, combined SiO2–ZnO NPs (with and without proline) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Foliar spray: Control (water), Proline (Pro), SiO2 NPs (Si), ZnO NPs (Zn), SiO2–ZnO NPs (Si + Zn), Proline + SiO2–ZnO NPs (Pro + Si + Zn) | Exogenous application of SiO2–ZnO NPs, especially in combination with proline, alleviated salt stress by increasing leaf chlorophyll, proline, K, Si, Zn content, and K/Na ratio, while reducing Na accumulation. Also enhanced nutrient content in straw and grains, crude protein in grains, and significantly improved biological, grain, and straw yields under salinity stress. The best performance was achieved with Pro + SiO2–ZnO NPs. | [115] |

| Salt stress—150 mM NaCl (hydroponic) | ZnO-NPs | Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) | Foliar spray: 50, 100, 150, 200 mg L−1 (10 mL per plant, front and back of leaves, seven consecutive days) | Improved shoot and root biomass, leaf area, plant height, and stem diameter; reduced MDA, H2O2, and O2−; enhanced antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, CAT); regulated expression of stress-related genes (↑ CNGC, NHX2, AHA3, HAK17; ↓ SKOR), stabilizing Na+/K+ ratio and improving salt tolerance. | [125] |

| Salt stress—150 mM NaCl | ZnO-NPs | Coffee (Coffea arabica) | Foliar spray: 50 and 100 mg L−1 | Mixed effects: increased proline (33–77%) and CAT activity (69–152%); reduced H2O2 (−18.7%); but also, higher Na+ accumulation (+45%), increased MDA (+3–50%), and reduced carotenoids at 100 mg L−1, limiting photoprotection. | [126] |

| Salt stress—150 mM NaCl | ZnO-NPs | Maize (Zea mays L.) | Foliar spray, 2 g L−1 | Improved growth and development under salinity: increased chlorophyll, enhanced fatty acid synthesis, higher protein and sugar metabolism, improved biomass (leaves, stalks, cobs, seeds), and reduced oxidative stress (lower H2O2 and MDA). | [127] |

| Saline–sodic stress (soil condition) | ZnO-NPs | Rice (Oryza sativa L.) | 30 kg ha−1 (mixed with the topsoil) | Reduced Na+ and MDA levels; increased K+, Zn2+, chloroplast pigments, quantum yield, PIABS, and active PSII reaction centers; improved electron and energy transfer in photosystem; enhanced photosynthesis and resistance to saline–sodic stress. | [128] |

| Salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) | ZnO NPs synthesized from Phragmites karka | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. seedlings) | Foliar/soil treatments at 20 mg L−1 and 50 mg L−1 | ZnO NPs improved overall growth under salinity; 50 mg L−1 (T20) enhanced shoot length (3-fold) and increased nodes and internodes; 20 mg L−1 (T16) increased leaf number. ZnO NPs effectively promoted salt resilience by stimulating growth parameters. | [129] |

| Salinity stress, saline soil (EC 7.8 dS m−1) | ZnO-NPs | Mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) | Seed priming with 50, 100, 500, 1000 mg L−1 | Improved germination %, shoot length, and shoot dry weight—increased SOD, POX, and proline, reduced lipid peroxidation and membrane injury. Low dose (50 mg L−1) was most effective, while 1000 mg L−1 negatively affected root traits in the sensitive genotype. | [118] |

| Salinity stress (0, 50, 100 mM NaCl) | ZnO-NPs (alone and in combination with biochar) | Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) | - Priming: 100 mg L−1 ZnO-NPs - Foliar spray: 100 mg L−1 ZnO-NPs - Biochar: 2.0% (w/w) soil amendment | Salinity (100 mM) caused the maximum reduction in growth and oxidative stress. ZnO-NPs alone improved growth, chlorophyll, gas exchange, and antioxidant activity. The combined ZnO-NPs + biochar treatment was most effective, reducing Na+ accumulation (−57.7% in roots, −61.3% in leaves), enhancing nutrient content, and improving nutritional quality and salinity tolerance. | [116] |

| Salt stress (50 mM NaCl) | Biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) were synthesized using Acacia nilotica leaf extract | Chili (Capsicum annuum L.) | Foliar spray: 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 ppm | Foliar ZnO-NPs (100 ppm) significantly enhanced shoot length (+38.6%), root length (+25.5%), chlorophyll content (+23.3%), phenolics (+12.5%), and zinc accumulation (+38.7%). Also reduced oxidative stress markers: MDA (−54.4%) and H2O2 (−33.1%). Overall, 100 ppm was the most effective treatment for growth and stress tolerance. | [121] |

| Salt stress (100 mM NaCl) | ZnO-NPs, SiO2 NPs (compared to ZnSO4 and K2SiO3) | Maize (Zea mays L.) | ZnO: 10 mg L−1, SiO2: 90 mg L−1, applied in hydroponic Hoagland solution | ZnO-NPs increased K+ concentration and K+/Na+ ratio, enhancing ionic homeostasis; SiO2-NPs improved osmotic adjustment and limited Na+ accumulation. Both improved biomass, chlorophyll content, and salinity tolerance index. | [130] |

| Salinity stress (50 mM NaCl, 33.3 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaCl + 16.6 mM CaCl2) | ZnO-NPs, SiO2 NPs | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | Foliar application, 100 mg L−1 | Under non-saline conditions, both NPs improved growth. SiO2 NPs increased biomass, root architecture, and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GR); ZnO NPs enhanced root biomass, root architecture, and leaf chlorophyll. Under CaCl2 stress, SiO2 NPs improved root growth, non-enzymatic antioxidants, and CAT, APX, and GR activity. ZnO NPs caused greater physiological damage under CaCl2 and NaCl + CaCl2 (impaired root development, reduced PSII efficiency). Overall, SiO2 NPs conferred partial tolerance; ZnO NPs were detrimental under combined stresses. | [31] |

| Salinity stress (1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 dS m−1 NaCl) | ZnO-NPs | Basil (Ocimum basilicum) | Foliar spray, 1.5–2.0 mg L−1 | Salinity reduced growth and photosynthesis, while increasing lipid peroxidation, electrolyte leakage (EL), and antioxidant markers. ZnO NPs (1.5–2.0 mg L−1) enhanced growth and photosynthetic traits, increased antioxidant activity, and reduced EL and lipid peroxidation. Most effective dose identified: 2.0 mg L−1. | [122] |

| Salinity stress 100 mM NaCl | ZnO-NPs and Salicylic Acid (SA) | Salvia varita (Salvia virgata) | Foliar application ZnO NPs: 20 mg L−1 SA: 500 μM foliar spray | Salinity decreased chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids; increased MDA, H2O2, phenolics, flavonoids, sugars, and proline. Elicitors (SA, ZnO NPs, SA + ZnO NPs) increased pigments, proline, sugars, phenolics, and flavonoids. They boosted antioxidant enzymes (CAT, GR, APX, SOD) a synergistic effect was observed, resulting in reduced oxidative stress and improved growth under salinity conditions. | [117] |

| Salinity stress 50 mM and 100 mM NaCl | ZnO-NPs | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) | 750 ppm ZnO NPs, seed priming for six h before sowing | Salinity reduced chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids, and increased MDA, H2O2, phenolics, flavonoids, sugars, and proline. Elicitors (SA, ZnO NPs, SA + ZnO NPs) increased pigments, proline, sugars, phenolics, flavonoids, and boosted antioxidant enzymes (CAT, GR, APX, SOD). Combination NaCl + SA + ZnO NPs: ↑ proline (+21.55%), ↑ sugars (+15.73%), ↓ MDA (−42.28%), ↓ H2O2 (−42.34%). A synergistic effect was observed, resulting in reduced oxidative stress and improved growth under salinity conditions. | [119] |

| Salinity stress (20, 40, 80, 120 mmol L−1 NaCl) | ZnO-NPs ZnO bulk | Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) | Foliar application, 50 mg L−1 (ZnO bulk and ZnO NPs) | Salt stress reduced growth, chlorophyll, K+ and Zn2+, and increased Na+, Cl−, MDA, and proline. ZnO bulk and ZnO NPs enhanced growth, nutrient uptake, and antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, APX, GPX, GR). ZnO bulk decreased MDA by 30–47% and proline by 1.6–6%; ZnO NPs decreased MDA by 31–58% and proline by 21–28%, showing stronger stress mitigation compared to bulk ZnO. | [120] |

| Abiotic Stress | Nanoparticles | Crop | Type of Application and Doses | Response Under the Effect of NPs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat stress (heatwave, 37 °C, 6 days) | ZnO-NPs | Rice (Oryza sativa L.) | Foliar spray: 50, 100, 200 mg L−1 (0.5 mL per plant day−1 for 6 d); life cycle: 100 mg L−1 (6.7 mL per plant day−1) | Increased grain yield (22.1%), protein (11.8%), and amino acids (77.5%). Enhanced nutrient accumulation (Zn, Mn, Cu, Fe, Mg ↑15.8–416.9%), chlorophyll (↑22–25%), Rubisco activity (↑21.2%), and antioxidant activity (↑27–31%). Reversed transcriptomic dysregulation, improved photosynthesis (↑74.4%), and stabilized phyllosphere microbial community under HW stress. | [131] |

| Heat stress (field conditions, summer 2022, Peshawar valley) | ZnO-NPs | Maize (Zea mays L.) | Seed priming: Control, 100 mg L−1, 150 mg L−1 Foliar spray (V8 stage): Control, 100 mg L−1, 150 mg L−1 | Foliar spray (150 mg L−1): ↑ leaf area, height, yield, Zn uptake (+53%); seed priming (150 mg L−1): ↑ plant height, yield, Zn uptake (+59.7%); improved chlorophyll, photosynthesis, CTD, reduced electrolyte leakage and HSPs. | [40] |

| Heat stress: 38 °C, 2 h day−1, 6 days | ZnO-NPs (biosynthesized) enriched with Lessertia frutescens leaf extract (CLE) | Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) | Foliar spray: CLE (2%) + ZnO NPs at 25, 50, 75 mg L−1 | CLE + ZnO NPs (50–75 mg L−1): ↑ growth, yield, chlorophylls, carotenoids, essential oil, phenolics, ascorbic acid, antioxidant enzymes (CAT, APX, SOD); ↓ MDA and electrolyte leakage under heat stress. | [132] |

| Heat stress (45 °C Day/34 °C night, 7 days) | ZnO-NPs | Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) | Foliar spray: 30, 60, 90 mg L−1; treatments: No heat stress (NHS), pretreatment before heat stress (BHS), post-treatment after heat stress (AHS) | ZnO-NPs (esp. 90 mg L−1) ↓ membrane damage, lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress; ↑ antioxidant systems and osmolytes. BHS > AHS: reversible chloroplast/mitochondria damage, improved growth and physiological performance. | [38] |

| Heat stress (37 °C) | ZnO-NPs | Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | 1 µg mL−1 in growth medium | ZnO-NPs alone did not alleviate TGS-GUS, but under heat stress, they enhanced transcriptional gene silencing, showing a synergistic effect between NPs and heat stress on genomic instability, which is modulated by developmental stage and heat duration. | [133] |

| Heat stress (24 °C vs. 28 °C; heatwave simulation) | ZnO-NPs | (Chlorella pyrenoidosa) | 1.0 mg L−1 | ZnO-NPs caused growth inhibition, which was stronger at 24 °C than at 28 °C. HW (28 °C) reduced ROS and cell damage, altered algal surface properties, and decreased Zn uptake. Metabolomics revealed disturbances in amino acids, fatty acids, and energy metabolism under ZnO-NPs stress, which were mitigated under HW, thereby improving algal adaptability. | [134] |

| Radiation stress 60 Gy gamma irradiation | ZnO–NPs | Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) | ZnO–NPs seed priming (0, 50, 100, 200 ppm for 24 h) | Maximum germination at 100 ppm ZnO–NPs (92%) and 100 ppm + 60 Gy (90%). Highest chlorophylls and carotenoids at 100 ppm + 60 Gy. Proline peaked (1.069 mg g−1 FW) at 200 ppm ZnO–NPs + 60 Gy. Anatomical changes: epidermal tissue thickened, especially at 200 ppm. Molecular (SCoT) markers revealed ZnO–NPs reduced gamma-induced genetic alterations. ZnO nanoparticles act as nanoprotective agents, mitigating radiation damage. | [135] |

| UV-B radiation stress (30 min/day for 15 days, hydroponic culture) | ZnO-NPs | Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) | Foliar spray: 50 and 100 mg L−1 (before UV-B exposure) | UV-B reduced root length (−40%), shoot FW (−17%), SDW (−15%), and stem thickness (−39%). ZnO-NPs improved growth: shoot FW (+56%, +63%), SDW (+40%, +79%), shoot length (+21%, +12%). At 100 mg L−1, enhanced stem thickness (+31%) and vascular tissues (xylem, phloem, collenchyma). Increased TPC (+8%), TFC (+30%), and antioxidant activity (DPPH ↑15.78% at 50 mg L−1). Mitigated UV-B-induced anatomical and physiological damage. | [136] |

| Heat stress (field, El Wadi El Gadeed, Egypt) | Zn-NPs Fe-NPs | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Foliar spray at 0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.0, and 10 ppm | Best performance observed at 10 ppm Zn-NPs and 0.25 ppm Fe-NPs. Enhanced yield in heat-sensitive cultivar (Gimmeza7). Increased antioxidant enzymes (GST, SOD, POX, CAT), decreased MDA (lipid peroxidation). The isozyme profile showed new bands linked to stress tolerance. Improved plant survival and yield under heat stress. | [138] |

| Heat stress (35/30 °C Day/night), drought stress (35% WHC), and combined drought + heat stress | Green-synthesized ZnO-NPs (Papaya fruit extract, 10 ppm) + PGPR (Pseudomonas sp.) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Foliar application of ZnO-NPs (10 ppm), alone or in combination with PGPR | Heat and drought stresses increased MDA and H2O2, resulting in reduced growth and pigment production. ZnO-NPs + PGPR improved biomass, photosynthetic pigments, nutrients, soluble sugars, proteins, and IAA. Combination treatment enhanced proline, ABA, antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POX, CAT, APX, GR, DHAR), and reduced electrolyte leakage, MDA, and H2O2. The synergistic effect provided stronger protection under combined stress. | [139] |

| Heat stress: 25/20 °C (control), 35/30 °C (moderate), 40/35 °C (severe) | ZnO-NPs | Snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) seedlings | 0, 50, 100, 200 mg L−1 foliar spraying | Heat stress reduced growth, chlorophyll, and antioxidant activity. ZnO-NPs alleviated inhibition by increasing chlorophyll (↑by 3.8–7.7%), carotenoids (↑by 4.9–11.7%), soluble sugars (↑by 12.7–44.8%), and proline (↑by 18.2–32.9%). Enhanced AsA-GSH cycle enzymes: APX (↑35.3–86.3%), DHAR (↑13.5–24.6%), MDHAR (↑58.5–81.5%), GR (↑8.6–19.7%), plus higher AsA, GSH, AsA/DHA, and GSH/GSSG ratios. Reduced MDA, electrolyte leakage, O2•−, and H2O2. Best effect at 100 mg L−1, conferring the highest heat tolerance. | [137] |

| Abiotic Stress | Nanoparticles | Crop | Type of Application and Doses | Response Under the Effect of NPs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy metal stress: wastewater contamination with Cadmium (Cd) and Chromium (Cr6+) | Biologically synthesized ZnO-NPs (from Shewanela sp.) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Foliar spray: 0, 25, 50, 100 mg L−1 applied at intervals for 40 days | 100 mg L−1 ZnO-NPs gave the best results. Cd in shoots ↓19.6%, 43.8%, 90.9% (at 25, 50, 100 mg L−1). Cr6+ in shoots ↓14.6%, 39.3%, 94.9% (at 25, 50, 100 mg L−1). Growth, germination, chlorophyll, total soluble sugars, total free amino acids, and ascorbic acid increased. Antioxidant enzymes (APX, SOD, POD, CAT) ↑. Oxidative stress markers (MDA, H2O2, EL, O2•−) ↓. ZnO-NPs alleviated heavy metal toxicity, improving growth and physiology. | [140] |

| Heavy metal stress: Cadmium (Cd) contamination | ZnO-NPs, Fe3O4-NPs, and combined NPs | Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) | Foliar spray: 50–400 mg L−1; optimal at 150 mg L−1 combined NPs | Combined NPs reduced Cd in roots (↓52.1%) and shoots (↓47.8%); biomass ↑42.9% (roots) and ↑100.2% (shoots). At 150 mg L−1, root Cd dropped from 0.619 to 0.245 mg g−1 and shoot Cd from 0.187 to 0.148 mg g−1. Transcriptomics: upregulated GST23, POD2 (antioxidant defense); downregulated transporters ABCC2, Nramp2, ABCG29, ABCG2 (Cd uptake ↓). Combined NPs synergistically enhanced growth, antioxidant capacity, and Cd resistance. | [141] |

| Heavy metal stress: Arsenic (As, 10 ppm) and Chromium (Cr, 10 ppm) | ZnO-NPs | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Foliar spray: 10, 20, 30 ppm ZnO-NPs, applied once after 14 days of germination | ZnO-NPs reduced As and Cr toxicity, improving morphological traits, physiology, antioxidant enzymes, and yield. Variety Faisalabad 2008 performed better than Aas 2011. ZnO-NPs decreased heavy metal accumulation, enhanced biochemical and antioxidant responses, and mitigated stress-induced yield losses. ZnO-NPs alleviated As and Cr toxicity, improving wheat growth and productivity. | [143] |

| Heavy metal stress: Cadmium (Cd, 19.2 mg kg−1 soil) | ZnO-NPs | Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) | Foliar spray: 100 mg L−1 ZnO-NPs | Cd stress reduced shoot height, biomass, and induced ROS accumulation, oxidative stress, and programmed cell death (PCD). ZnO-NPs enhanced antioxidant activity, cell membrane stability, osmotic homeostasis, and ultrastructural integrity, thereby reducing ROS and mitigating PCD. ZnO-NPs upregulated antioxidant enzymes and PCD-related genes, enriched pathways in cell death and porphyrin/chlorophyll metabolism. ZnO-NPs alleviated Cd toxicity by promoting redox balance and enhancing molecular defenses, thereby increasing tolerance. | [148] |