Regulation of Plasmodesmata Function Through Lipid-Mediated PDLP7 or PDLP5 Strategies in Arabidopsis Leaf Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

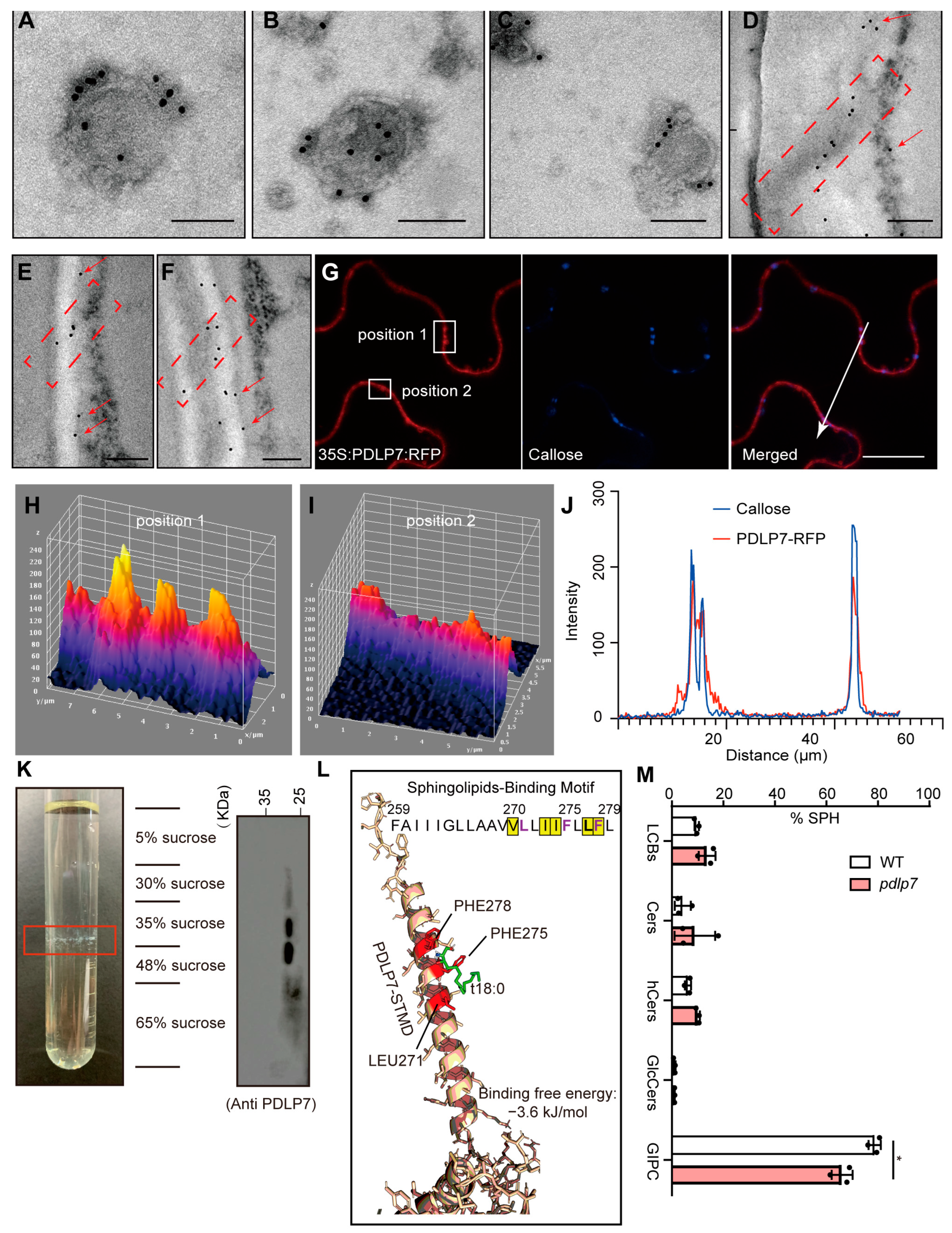

2.1. PDLP7 Is Located in the PD Lipid Rafts and Also Regulates PD Sphingolipids

2.2. PDLP7 Could Form a Homologous Polymer in the Presence of Sphingosine

2.3. PDLP7 Regulates the Membrane Liquid-Ordered/Disordered Phases Through Interaction with Sphingolipids

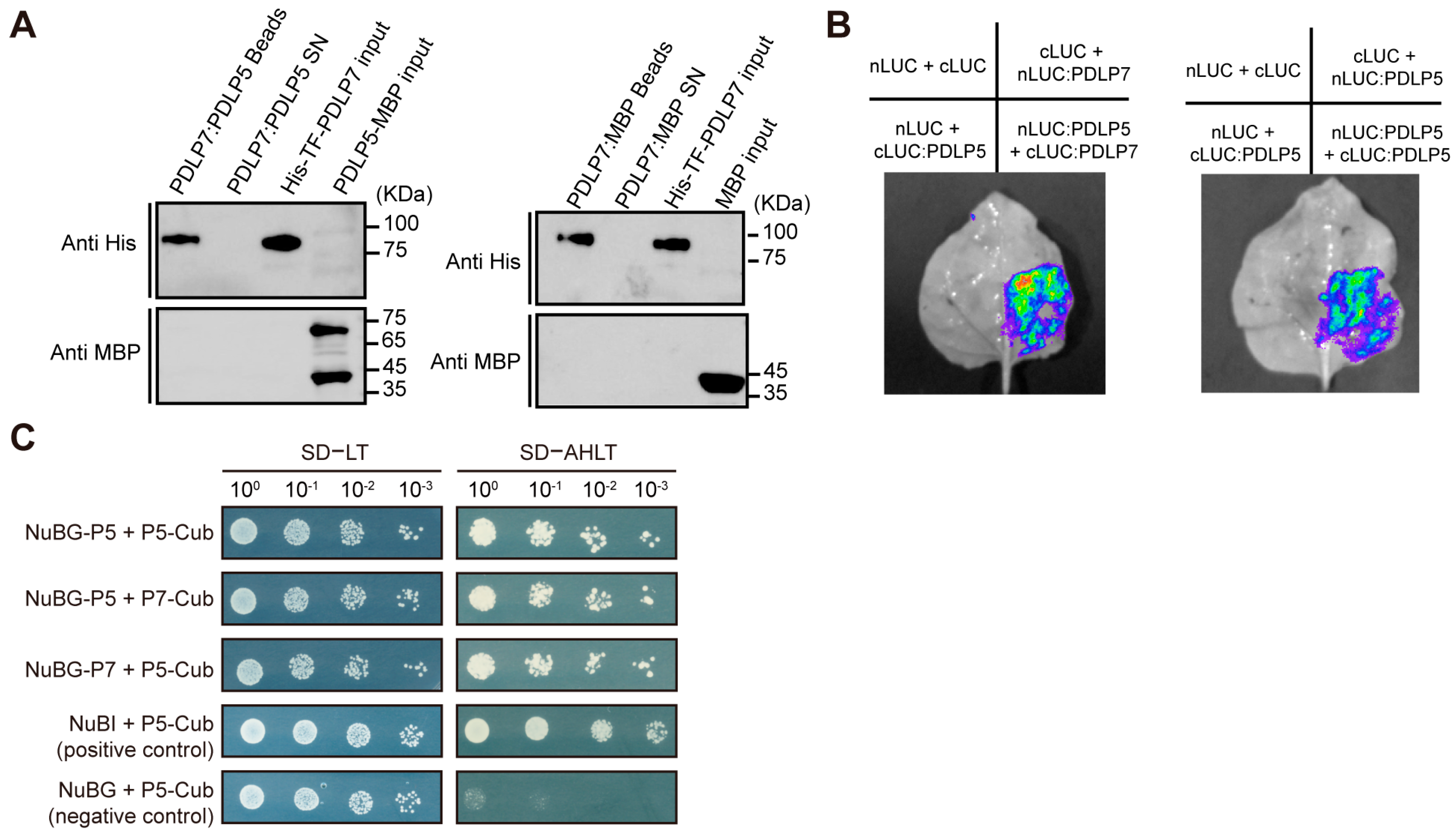

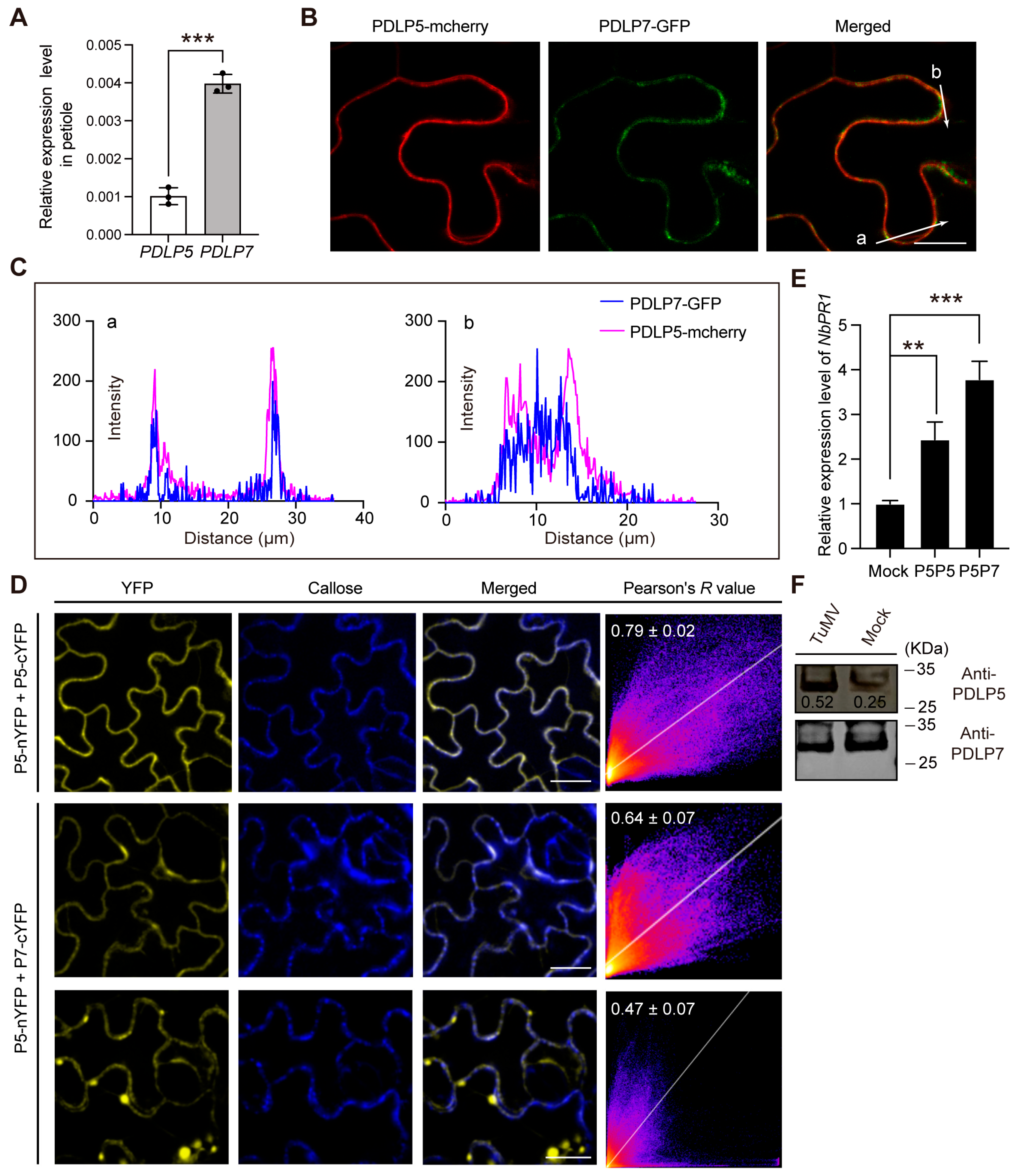

2.4. PDLP7 Interacted with PDLP5 In Vivo

2.5. The Overexpression of PDLP5 and PDLP7 Leads to Upregulation of SA-Characterized Gene PR1 in the Cells

3. Discussion

3.1. Determinants of the Localization of PDLP Protein on PDs

3.2. Correlation Between PDLP7, Lipidomics, and Lipid Order

3.3. Plant Cells Possess at Least Two Regulatory Models for Sphingolipid–PDLPs

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Transient Transformation, Fluorescence Observation, and Callose Staining

4.3. Isolation of PD Fraction and PD Lipid Raft

4.4. PD Sphingolipidomic Measurement

4.5. Immuno-Electron Microscopy

4.6. Di-4-ANEPPDHQ Staining

4.7. Molecular Docking of PDLP7 Protein and t18:0

4.8. BiFC and BiLC

4.9. Dual-Membrane Yeast Two-Hybrid Systems

4.10. Pull-Down Assay

4.11. Purification of His-TF-PDLP7

4.12. Preparation of Protein–Liposomes and Crosslinking

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PD | Plasmodesmata |

| PDLP | plasmodesmata-localized protein |

| t18:0 | phytosphinganine |

| POPC | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| BiFC | Bimolecular fluorescence complementation |

| BiLC | Bimolecular luciferase complementation |

| GIPC | glycosyl inositol phosphorylceramides |

| PR1 | pathogenesis-related protein 1 |

| PLANT DEFENSIN | |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative reverse transcription PCR |

| GUS | β-galactosidase |

| NASC | Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre |

| At | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| SD | Synthetic defined |

| TuMV | Turnip mosaic virus |

References

- Rustom, A.; Saffrich, R.; Markovic, I.; Walther, P.; Gerdes, H.H. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science 2004, 303, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, W.J.; Grison, M.S.; Bayer, E.M. Shaping intercellular channels of plasmodesmata: The structure-to-function missing link. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 69, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonaviciene, B.; Newcombe, E.; Gresty, A.; Benitez-Alfonso, Y. Plasmodesmata wall biomechanics: Challenges and opportunities. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, eraf392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Adnan, M. Gatekeepers and Gatecrashers of the Symplasm: Cross-Kingdom Effector Manipulation of Plasmodesmata in Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J. Remorin interacting with PCaP1 impairs Turnip mosaic virus intercellular movement but is antagonised by VPg. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 2122–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, N.L.; Voss, U.; Janes, G.; Bennett, M.J.; Wells, D.M.; Band, L.R. Auxin fluxes through plasmodesmata modify root-tip auxin distribution. Development 2020, 147, dev181669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, G.; Medzihradszky, A.; Suzaki, T.; Lohmann, J.U. A mechanistic framework for noncell autonomous stem cell induction in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14619–14624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, R.; Lee, J.-Y. Plasmodesmata in integrated cell signalling: Insights from development and environmental signals and stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 6337–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Lexy, R.; Kasai, K.; Clark, N.; Fujiwara, T.; Sozzani, R.; Gallagher, K.L. Exposure to heavy metal stress triggers changes in plasmodesmatal permeability via deposition and breakdown of callose. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3715–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsbury, S.; Kirk, P.; Benitez-Alfonso, Y. Emerging models on the regulation of intercellular transport by plasmodesmata-associated callose. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 69, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grison, M.S.; Brocard, L.; Fouillen, L.; Nicolas, W.; Wewer, V.; Doermann, P.; Nacir, H.; Benitez-Alfonso, Y.; Claverol, S.; Germain, V.; et al. Specific Membrane Lipid Composition Is Important for Plasmodesmata Function in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1228–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Sancho, J.; Smokvarska, M.; Dubois, G.; Glavier, M.; Sritharan, S.; Moraes, T.S.; Moreau, H.; Dietrich, V.; Platre, M.P.; Paterlini, A.; et al. Plasmodesmata act as unconventional membrane contact sites regulating intercellular molecular exchange in plants. Cell 2025, 188, 958–977.e923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.M.; Rentero, C.; Magenau, A.; Abu-Siniyeh, A.; Gaus, K. Quantitative imaging of membrane lipid order in cells and organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 7, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iswanto, A.B.B.; Kim, J.-Y. Lipid Raft, Regulator of Plasmodesmal Callose Homeostasis. Plants 2017, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronnier, J.; Crowet, J.M.; Habenstein, B.; Nasir, M.N.; Bayle, V.; Hosy, E.; Platre, M.P.; Gouguet, P.; Raffaele, S.; Martinez, D.; et al. Structural basis for plant plasma membrane protein dynamics and organization into functional nanodomains. eLife 2017, 6, e26404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ruan, Y.-L.; Zhou, N.; Wang, F.; Guan, X.; Fang, L.; Shang, X.; Guo, W.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, T. Suppressing a Putative Sterol Carrier Gene Reduces Plasmodesmal Permeability and Activates Sucrose Transporter Genes during Cotton Fiber Elongation. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2027–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, E.; Thomas, C.; Maule, A. Symplastic domains in the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem correlate with PDLP1 expression patterns. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, R.; Kaldis, A.; Spetz, C.J.; Borah, B.K.; Voloudakis, A. Silencing of Putative Plasmodesmata-Associated Genes PDLP and SRC2 Reveals Their Differential Involvement during Plant Infection with Cucumber Mosaic Virus. Plants 2025, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, M.; Gan, L.; Zhou, T.; Xuan, Y. Plasmodesmata Function and Callose Deposition in Plant Disease Defense. Plants 2024, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.H.; Shine, M.B.; de Lorenzo, L.; Yu, K.; Cui, W.; Navarre, D.; Hunt, A.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Kachroo, A.; Kachroo, P. Plasmodesmata Localizing Proteins Regulate Transport and Signaling during Systemic Acquired Immunity in Plants. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.W.; Chen, Q.F.; Chye, M.L. Arabidopsis thaliana Acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP6 interacts with plasmodesmata-located protein PDLP8. Plant Signal Behav. 2017, 12, e1359365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saatian, B.; Austin, R.S.; Tian, G.; Chen, C.; Cui, Y. Analysis of a novel mutant allele of GSL8 reveals its key roles in cytokinesis and symplastic trafficking in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tee, E.E.; Johnston, M.G.; Papp, D.; Faulkner, C. A PDLP-NHL3 complex integrates plasmodesmal immune signaling cascades. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2216397120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.H.; Chen, X.; Guo, H.S.; Ju, B.H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, G.Z.; Zhou, Q.H.; Qin, Y.M.; et al. Phytosphinganine affects plasmodesmata permeability via facilitating PDLP5-stimulated callose accumulation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, W.W.; Gao, J.; Wu, Z.G.; Du, J.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhu, Y.X. Arabidopsis PDLP7 modulated plasmodesmata function is related to BG10-dependent glucosidase activity required for callose degradation. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 3075–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudier, F.; Fernandez, A.G.; Fujita, M.; Himmelspach, R.; Borner, G.H.; Schindelman, G.; Song, S.; Baskin, T.I.; Dupree, P.; Wasteneys, G.O.; et al. COBRA, an Arabidopsis extracellular glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol-anchored protein, specifically controls highly anisotropic expansion through its involvement in cellulose microfibril orientation. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.L.; Bayer, E.M.; Ritzenthaler, C.; Fernandez-Calvino, L.; Maule, A.J. Specific targeting of a plasmodesmal protein affecting cell-to-cell communication. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Robles Luna, G.; Arighi, C.N.; Lee, J.-Y. An evolutionarily conserved motif is required for Plasmodesmata-located protein 5 to regulate cell-to-cell movement. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, G.R.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Liao, L.; Lee, J.Y. Targeting of plasmodesmal proteins requires unconventional signals. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 3035–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, M.C.; Wirthmueller, L.; Sklenar, J.; Findlay, K.; Piquerez, S.J.; Jones, A.M.; Robatzek, S.; Jones, J.D.; Faulkner, C. The plasmodesmal protein PDLP1 localises to haustoria-associated membranes during downy mildew infection and regulates callose deposition. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sancho, J.; Vanneste, S.; Lee, E.; McFarlane, H.E.; Esteban Del Valle, A.; Valpuesta, V.; Friml, J.; Botella, M.A.; Rosado, A. The Arabidopsis synaptotagmin1 is enriched in endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites and confers cellular resistance to mechanical stresses. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, K.; Mongrand, S.; Beney, L.; Simon-Plas, F.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P. Differential effect of plant lipids on membrane organization: Specificities of phytosphingolipids and phytosterols. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 5810–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ke, M.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Ji, C.; Tran, T.M.; Yang, L.; et al. Salicylic acid-mediated plasmodesmal closure via Remorin-dependent lipid organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21274–21284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, S.-L.; Montes-Serey, C.; Walley, J.W.; Aung, K. PLASMODESMATA-LOCATED PROTEIN 6 regulates plasmodesmal function in Arabidopsis vasculature. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3543–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comtet, J.; Turgeon, R.; Stroock, A.D. Phloem Loading through Plasmodesmata: A Biophysical Analysis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, K.; van Bel, A.J. Dynamics of plasmodesmal connectivity in successive interfaces of the cambial zone. Planta 2010, 231, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Liu, N.-J.; Hu, J.-R.; Shi, H.; Gao, J.; Zhu, Y.-X. Regulation of Plasmodesmata Function Through Lipid-Mediated PDLP7 or PDLP5 Strategies in Arabidopsis Leaf Cells. Plants 2026, 15, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010145

Chen X, Liu N-J, Hu J-R, Shi H, Gao J, Zhu Y-X. Regulation of Plasmodesmata Function Through Lipid-Mediated PDLP7 or PDLP5 Strategies in Arabidopsis Leaf Cells. Plants. 2026; 15(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xin, Ning-Jing Liu, Jia-Rong Hu, Hao Shi, Jin Gao, and Yu-Xian Zhu. 2026. "Regulation of Plasmodesmata Function Through Lipid-Mediated PDLP7 or PDLP5 Strategies in Arabidopsis Leaf Cells" Plants 15, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010145

APA StyleChen, X., Liu, N.-J., Hu, J.-R., Shi, H., Gao, J., & Zhu, Y.-X. (2026). Regulation of Plasmodesmata Function Through Lipid-Mediated PDLP7 or PDLP5 Strategies in Arabidopsis Leaf Cells. Plants, 15(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010145