Genome-Wide Analysis of Nelumbo nucifera UXS Family Genes: Mediating Dwarfing and Aquatic Salinity Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of UXS Family Members in N. nucifera

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of the NnUXS Family

2.3. Structure Analysis of UXS Family Members in N. nucifera

2.4. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoters of NnUXS Family Genes

2.5. Gene Replication and Synteny Analysis of UXS Family Genes

2.6. Structures Prediction and Molecular Docking of NnUXS Family Members

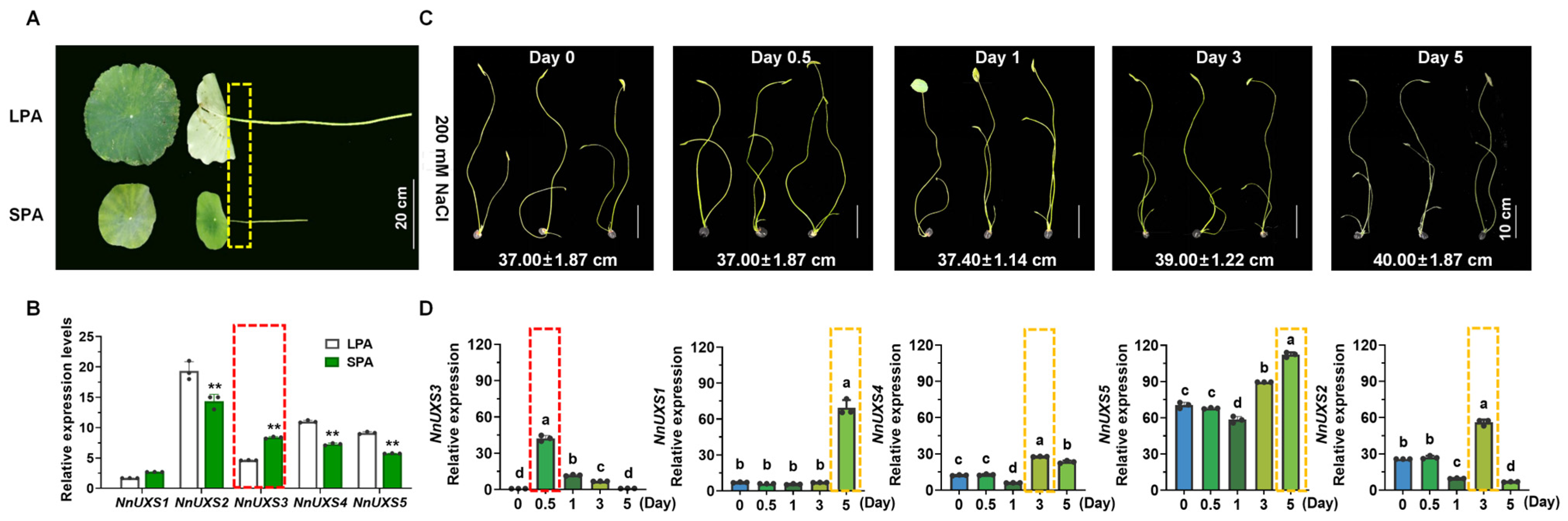

2.7. Identification of NnUXS3 as a Candidate Gene for Plant Architecture Dwarfing and Salt Tolerance in N. nucifera

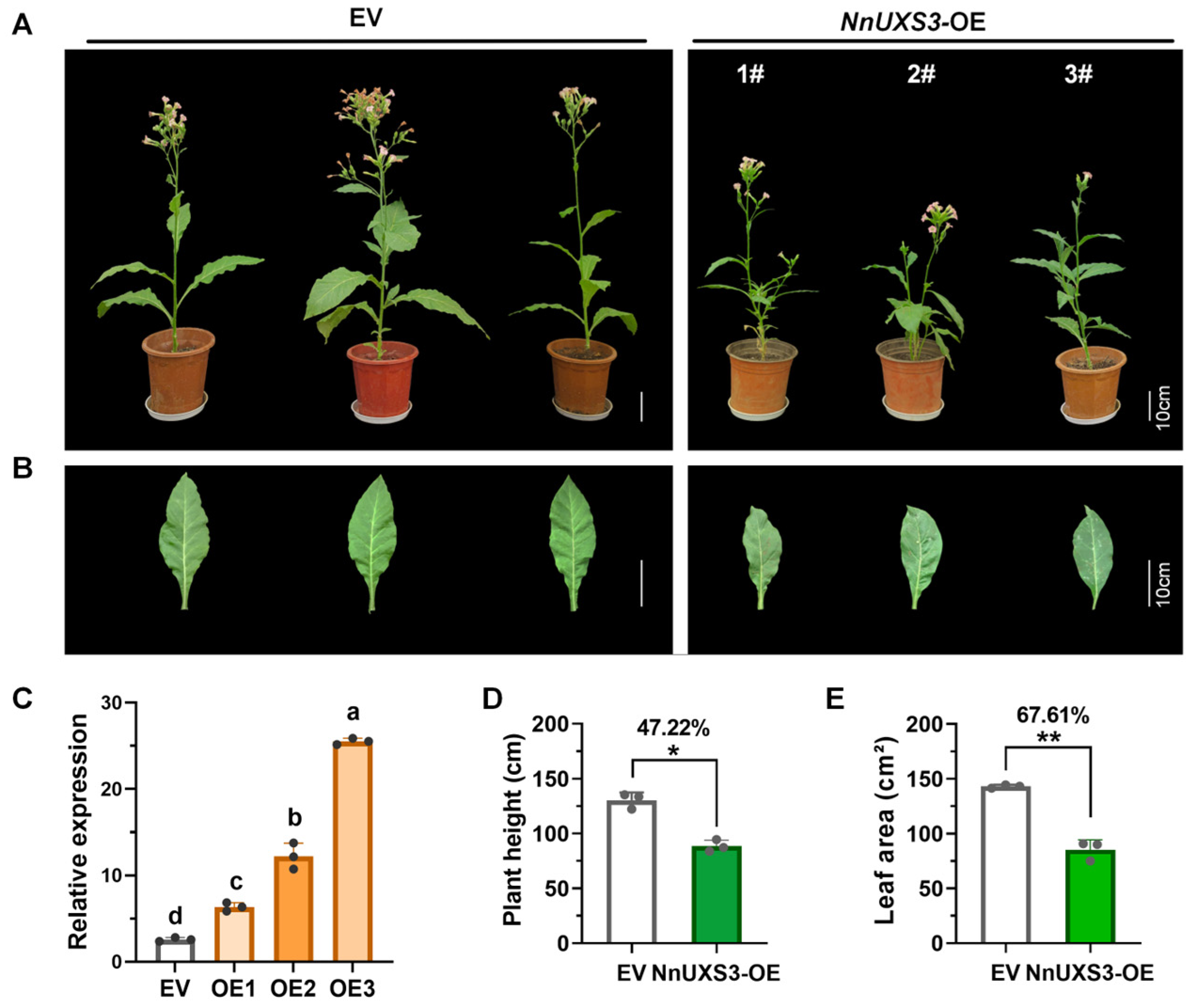

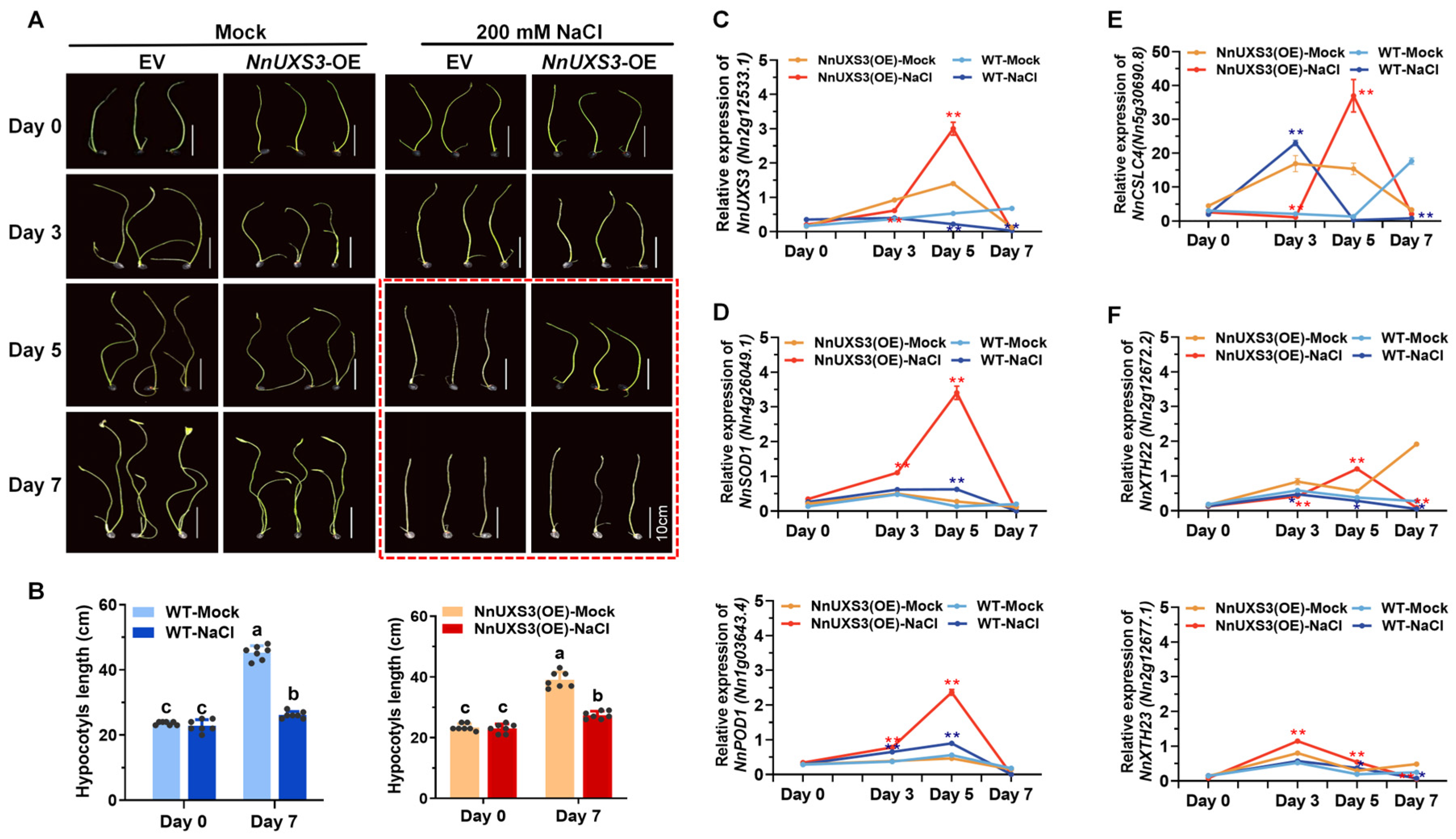

2.8. Functional Validation of NnUXS3 in Plant Dwarfing and Lotus Salt Tolerance

3. Discussion

3.1. Evolutionary Divergence and Functional Specialization of the Lotus UXS Gene Family in Aquatic Adaptation

3.2. NnUXS3 Mediated Growth-Defense Tradeoffs via Cell Wall Remodeling: Mechanistic Insights and Implications for Breeding

3.3. Potential Complex Regulatory Networks of NnUXS3 Orchestrating Growth and Abiotic Stress Responses

3.4. Advantages of Lotus Transient Transformation Technology and Its Application in Gene Function Verification

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Sample Collection

4.2. Salinity Stress Treatment

4.3. Identification and Property Analysis of NnUXS Family Genes

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.5. Chromosome Localization, Motif Distribution and Gene Structure of NnUXS Family Genes

4.6. Transcription Factor Binding Sites Analysis and Cis-Acting Elements Prediction of NnUXSs Promoter

4.7. Gene Duplication and Synteny Analyses

4.8. Secondary, 3D Structure and Molecular Docking Analysis of NnUXS Family Genes

4.9. Nucleic Acid Isolation and qRT-PCR Analysis

4.10. Construction of Overexpression Vectors and Genetic Transformation

4.11. Transient Gene Expression in N. nucifera Seedlings

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Somerville, C.; Bauer, S.; Brininstool, G.; Facette, M.; Hamann, T.; Milne, J.; Osborne, E.; Paredez, A.; Persson, S.; Raab, T.; et al. Toward a systems approach to understanding plant cell walls. Science 2004, 306, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Z.; Zhang, R.; Feng, S.Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Wang, Y.T.; Fan, C.F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Schneider, R.; Xia, T.; et al. Three AtCesA6-like members enhance biomass production by distinctively promoting cell growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Z.; Zhang, R.; Tang, Y.W.; Peng, C.L.; Wu, L.M.; Feng, S.Q.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.T.; Du, X.Z.; Peng, L.C. Cotton CSLD3 restores cell elongation and cell wall integrity mainly by enhancing primary cellulose production in the Arabidopsis cesa6 mutant. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 101, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, H.Q.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Z.P.; Zhao, W.Y.; Wang, B.; et al. Cell wall remodeling confers plant architecture with distinct wall structure in Nelumbo nucifera. Plant J. 2024, 120, 1392–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.A.; Wilson, S.M.; Hrmova, M.; Harvey, A.J.; Shirley, N.J.; Medhurst, A.; Stone, B.A.; Newbigin, E.J.; Bacic, A.; Fincher, G.B. Cellulose synthase-like CslF genes mediate the synthesis of cell wall (1,3;1,4)-Beta-D-Glucans. Science 2006, 311, 1940–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, R.J.; Yang, D.M.; Zhao, Y.J.; Kuang, J.H.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhang, R.; Hu, H.Z. Side chain of confined xylan affects cellulose integrity leading to bending stem with reduced mechanical strength in ornamental plants. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 329, 121787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.T.; Hu, H.Z.; Li, F.C.; Li, M.; Ragauskas, A.; Xia, T.; Han, H.Y.; Tang, J.F.; et al. Single-molecular insights into the breakpoint of cellulose nanofibers assembly during saccharification. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Z.; Zhang, R.; Dong, S.C.; Li, Y.; Fan, C.F.; Wang, Y.T.; Xia, T.; Chen, P.; Wang, L.Q.; Feng, S.Q.; et al. AtCSLD3 and GhCSLD3 mediate root growth and cell elongation downstream of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, D.M.; Xia, W.N.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H.Q.; Chen, L.Q.; Hu, H.Z. Genome-wide analysis of CSL family genes involved in petiole elongation, floral petalization, and response to salinity stress in Nelumbo nucifera. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Fang, R.Q.; Deng, R.F.; Li, J.X. The OsmiRNA166b-OsHox32 pair regulates mechanical strength of rice plants by modulating cell wall biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1468–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endler, A.; Kesten, C.; Schneider, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ivakov, A.; Froehlich, A.; Funke, N.; Persson, S. A mechanism for sustained cellulose synthesis during salt stress. Cell 2015, 162, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.Z.; Zayed, O.; Zeng, F.S.; Liu, C.X.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, P.P.; Hsu, C.C.; Tuncil, Y.E.; Tao, W.A.; Carpita, N.C.; et al. Arabinose biosynthesis is critical for salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.H.; Li, Z.Y.; Lu, H.J.; Huo, L.; Wang, Z.B.; Wang, Y.C.; Ji, X.Y. The NAC protein from tamarix hispida, ThNAC7, confers salt and osmotic stress tolerance by increasing reactive oxygen species scavenging capability. Plants 2019, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.M.; Mota, T.R.; Salatta, F.V.; Sinzker, R.C.; Končitíková, R.; Kopečný, D.; Simister, R.; Silva, M.; Goeminne, G.; Morreel, K.; et al. Cell wall remodeling under salt stress: Insights into changes in polysaccharides, feruloylation, lignification, and phenolic metabolism in maize. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 2172–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lee, B.H.; Dellinger, M.; Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S.; Nothnagel, E.A.; Zhu, J.K. A cellulose synthase-like protein is required for osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010, 63, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.J. Nucleotide sugar interconversions and cell wall biosynthesis: How to bring the inside to the outside. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004, 7, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.H. Secondary cell walls: Biosynthesis, patterned deposition and transcriptional regulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacete, L.; Mélida, H.; Miedes, E.; Molina, A. Plant cell wall-mediated immunity: Cell wall changes trigger disease resistance responses. Plant J. 2018, 93, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, R.Q.; Teng, Q.; Haghighat, M.; Yuan, Y.; Furey, S.T.; Dasher, R.L.; Ye, Z.H. Cytosol-Localized UDP-Xylose synthases provide the major source of UDP-Xylose for the biosynthesis of Xylan and Xyloglucan. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharples, S.C.; Fry, S.C. Radioisotope ratios discriminate between competing pathways of cell wall polysaccharide and RNA biosynthesis in living plant cells. Plant J. 2007, 52, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, A.; Moraga, C.; Araya, M.; Moreno, A. Overview of nucleotide sugar transporter gene family functions across multiple species. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3150–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, H.; Saez-Aguayo, S.; Reyes, F.C.; Orellana, A. The inside and outside: Topological issues in plant cell wall biosynthesis and the roles of nucleotide sugar transporters. Glycobiology 2016, 26, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, B.Q.; Zhao, X.H.; Zhou, C.; Zeng, W.; Ren, J.L.; Ebert, B.; Beahan, C.T.; Deng, X.M.; Zeng, Q.Y.; Zhou, G.K.; et al. Role of UDP-Glucuronic acid decarboxylase in xylan biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, N.; Dang, Z.J.; Wang, M.H.; Cao, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.T.; Tang, Y.J.; Huang, Y.W.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Q.; et al. FRAGILE CULM 18 encodes a UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase required for xylan biosynthesis and plant growth in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2320–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, C.M.; Rautengarten, C.; Duan, E.; Zhu, J.P.; Zhu, X.P.; Lei, J.; Peng, C.; Wang, Y.L.; et al. BRITTLE PLANT1 is required for normal cell wall composition and mechanical strength in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.D.; Bar-Peled, M. Biosynthesis of UDP-xylose. Cloning and characterization of a novel Arabidopsis gene family, UXS, encoding soluble and putative membrane-bound UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase isoforms. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 2188–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen-Miller, J.; Lindner, P.; Xie, Y.; Villa, S.; Wooding, K.; Clarke, S.G.; Loo, R.R.; Loo, J.A. Thermal-stable proteins of fruit of long-living Sacred Lotus Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn var. China Antique. Trop. Plant Biol. 2013, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.J.; Wang, L.; Weng, C.Y.; Yen, J.H. Antioxidant activity of methanol extract of the lotus leaf (Nelumbo nucifera Gertn.). Am. J. Chin. Med. 2003, 31, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.A.; Kim, J.E.; Chung, H.Y.; Choi, J.S. Antioxidant principles of Nelumbo nucifera stamens. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2003, 26, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.J.; Yokozawa, T.; Rhyu, D.Y.; Kim, S.C.; Shibahara, N.; Park, J.C. Study on the inhibitory effects of Korean medicinal plants and their main compounds on the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Wahile, A.; Mukherjee, K.; Saha, B.P.; Mukherjee, P.K. Antioxidant activity of Nelumbo nucifera (sacred lotus) seeds. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 104, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Z.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Xiao, M.G.; Liu, H.; Quan, R.D.; Zhang, H.W.; Hang, R.F.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z. Cellulose synthase-like protein OsCSLD4 plays an important role in the response of rice to salt stress by mediating abscisic acid biosynthesis to regulate osmotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Xu, J.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, H.W. The protective effect of cold acclimation on the low temperature stress of the lotus (Nelumbo nucifera). Hortic. Sci. 2022, 49, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartapetian, B.B.; Andreeva, I.N.; Generozova, I.P.; Polyakova, L.I.; Maslova, I.P.; Dolgikh, Y.I.; Stepanova, A.Y. Functional electron microscopy in studies of plant response and adaptation to anaerobic stress. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, M.; Liu, Q.; Miura, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.P.; Hsu, C.C.; Liu, X.; Fu, L.W.; Hou, Y.J.; Du, Y.Y.; Xie, S.J.; Zhang, C.G.; et al. Reciprocal regulation of the TOR kinase and ABA receptor balances plant growth and stress response. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 100–112.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.K. Thriving under stress: How plants balance growth and the stress response. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.K.; Fan, N.N.; Zhang, Y.H.; Sun, L.J.; Su, L.T.; Wen, W.W.; Lv, A.; Dai, X.Y.; Gao, L.; Shi, F.L.; et al. The MsNAC73-MsMPK3 complex modulates salt tolerance and shoot branching of Alfalfa via activating MsPG2 and MsPAE12 Expressions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 5635–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, S.S.; Huang, W.T.; He, C.C.; Wu, B.W.; Duan, H.L.; Ruan, J.J.; Zhao, Q.Z.; Fang, Z.M. Transcription factor OsMYB2 triggers amino acid transporter OsANT1 expression to regulate rice growth and salt tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiae559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.M.; Chen, Y.W.; He, Y.T.; Song, J.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, M.Y.; Zheng, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, H.Z. Transcriptome analysis reveals association of E-Class AmMADS-Box genes with petal malformation in Antirrhinum majus L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Duan, X.B.; Ding, X.D.; Chen, C.; Zhu, D.; Yin, K.D.; Cao, L.; Song, X.W.; Zhu, P.H.; Li, Q.; et al. A novel AP2/ERF family transcription factor from Glycine soja, GsERF71, is a DNA binding protein that positively regulates alkaline stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2017, 94, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Cho, J.I.; Han, M.; Ahn, C.H.; Jeon, J.S.; An, G.; Park, P.B. The ABRE-binding bZIP transcription factor OsABF2 is a positive regulator of abiotic stress and ABA signaling in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkolnik, D.; Finkler, A.; Pasmanik-Chor, M.; Fromm, H. Calmodulin-Binding Transcription Activator 6: A key regulator of Na+ homeostasis during germination. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.H.; Bao, X.X.; Zhi, Y.L.; Wu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yin, X.H.; Zeng, L.Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; He, W.L.; et al. Overexpression of a MYB family gene, OsMYB6, increases drought and salinity stress tolerance in transgenic rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, R.L.; Yang, X.P.; Ju, Q.; Li, W.Q.; Lü, S.; Tran, L.P.; Xu, J. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB49 modulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by modulating the cuticle formation and antioxidant defence. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1925–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.H.; Wan, H.; Tang, J.; Ni, Z.Y. The sea-island cotton GbTCP4 transcription factor positively regulates drought and salt stress responses. Plant Sci. 2022, 322, 111329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Shi, X.X.; He, L.; Guo, Y.; Zang, D.D.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, W.H.; Wang, Y.C. Arabidopsis thaliana trihelix transcription factor AST1 mediates salt and osmotic stress tolerance by binding to a novel AGAG-Box and some GT motifs. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 946–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Fan, C.F.; Hu, H.Z.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, Y.M.; Peng, L.C. Genetic modification of plant cell walls to enhance biomass yield and biofuel production in bioenergy crops. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.Z.; Pan, W.; Tian, J.X.; Li, B.L.; Zhang, D.Q. The UDP-glucuronate decarboxylase gene family in Populus: Structure, expression, and association genetics. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Peled, M.; O’Neill, M.A. Plant nucleotide sugar formation, interconversion, and salvage by sugar recycling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2011, 62, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautengarten, C.; Birdseye, D.; Pattathil, S.; McFarlane, H.E.; Saez-Aguayo, S.; Orellana, A.; Persson, S.; Hahn, M.G.; Scheller, H.V.; Heazlewood, J.L.; et al. The elaborate route for UDP-arabinose delivery into the Golgi of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4261–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.L.; Zhang, M.C.; Ye, J.H.; Hu, D.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.R.; Sun, Y.F.; Wang, S.; Yuan, X.P.; et al. Brittle culm 25, which encodes an UDP-xylose synthase, affects cell wall properties in rice. Crop J. 2023, 11, 2214–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wang, Q.W.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Shen, T.; Jiang, J.J.; Cui, Z.Z.; Li, K.Y.; Yang, Q.Q.; Jiang, M.Y. OsDMI3-mediated OsUXS3 phosphorylation improves oxidative stress tolerance by modulating OsCATB protein abundance in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.D.; Zhao, Y.; Shan, D.Q.; Shi, K.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.T.; Wang, N.; Zhou, J.Z.; Yao, J.Z.; Xue, Y.; et al. MdWRKY9 overexpression confers intensive dwarfing in the M26 rootstock of apple by directly inhibiting brassinosteroid synthetase MdDWF4 expression. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M.; Master, V.; Waites, R.; Davies, B. TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length and leaf shape in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 68, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.F.; Song, Y.L.; Huang, Y.L.; Zhou, S.L.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhou, D.X. The interaction between rice ERF3 and WOX11 promotes crown root development by regulating gene expression involved in cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjuna, G.; Mallikarjuna, K.; Reddy, M.K.; Kaul, T. Expression of OsDREB2A transcription factor confers enhanced dehydration and salt stress tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 33, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Zou, H.F.; Wang, H.W.; Zhang, W.K.; Ma, B.; Zhang, J.S.; Chen, S.Y. Soybean GmMYB76, GmMYB92, and GmMYB177 genes confer stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.L.; Qanmber, G.; Li, J.; Pu, M.L.; Chen, G.Q.; Li, S.D.; Liu, L.; Qin, W.Q.; Ma, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Identification and characterization of the ERF subfamily B3 group revealed GhERF13.12 improves salt tolerance in upland cotton. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 705883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Sun, H.; Liu, J.; Lin, J.; Zhang, X.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; Deng, X.; Yang, D.; et al. Comparative analyses of American and Asian lotus genomes reveal insights into petal color, carpel thermogenesis and domestication. Plant J. 2022, 110, 1498–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Deng, X.B.; Zhang, M.H.; Sun, H.; Gao, L.; Song, H.Y.; Xin, J.; Ming, R.; Yang, D.; et al. Transcription factor NnMYB5 controls petal color by regulating GLUTATHIONE S-TRANSFERASE2 in Nelumbo nucifera. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Suda, I.; Miyagawa, I.; Matoh, T. Purification and cDNA cloning of UDP-D-glucuronate carboxy-lyase (UDP-D-xylose synthase) from pea seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Hu, H.Z.; Wang, Y.M.; Hu, Z.; Ren, S.F.; Li, J.Y.; He, B.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Xia, T.; Chen, P.; et al. A novel rice fragile culm 24 mutant encodes a UDP-glucose epimerase that affects cell wall properties and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2956–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higo, K.; Ugawa, Y.; Iwamoto, M.; Korenaga, T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.N.; Su, Y.L.; Song, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, X.M.; Zu, F.; Hu, H.Z. Cellulose synthase superfamily key in DAMPs-triggered immunity against Sclerotinia stem rot in Brassica napus. Plant Stress 2025, 18, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, W.; Usadel, B.; Stitt, M.; Reindl, A.; Ehrhardt, T.; Sonnewald, U.; Bornke, F. Large-scale phenotyping of transgenic tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum) to identify essential leaf functions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | LOC | AA (aa) | Mw (KDa) | PI | Instability Index | Aliphatic Index | GRAVY | TMHs | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NnUXS1 | Nn1g01140.1 | LOC104602248 | 414 | 46.005 | 10.11 | 50.72 | 82.2 | −0.27 | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| NnUXS2 | Nn1g08189.2 | LOC104587515 | 455 | 50.197 | 9.59 | 34.41 | 83.41 | −0.251 | 1 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| NnUXS3 | Nn2g12533.1 | LOC104612322 | 433 | 47.831 | 9.62 | 33.24 | 79.28 | −0.221 | 2 | Cytoplasm |

| NnUXS4 | Nn4g26366.1 | LOC104611461 | 438 | 48.409 | 10 | 46.98 | 83.04 | −0.226 | 1 | Nucleus |

| NnUXS5 | Nn8g40216.3 | LOC104605367 | 431 | 47.671 | 9.73 | 36.65 | 80.12 | −0.225 | 2 | Cytoplasm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Mao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, X.; Chen, L.; Hu, H. Genome-Wide Analysis of Nelumbo nucifera UXS Family Genes: Mediating Dwarfing and Aquatic Salinity Tolerance. Plants 2026, 15, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010116

Wang L, Zheng X, Liu Y, Mao Q, Chen Y, Zhao L, Cheng X, Chen L, Hu H. Genome-Wide Analysis of Nelumbo nucifera UXS Family Genes: Mediating Dwarfing and Aquatic Salinity Tolerance. Plants. 2026; 15(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Li, Xingyan Zheng, Yajun Liu, Qian Mao, Yiwen Chen, Lin Zhao, Xiaomao Cheng, Longqing Chen, and Huizhen Hu. 2026. "Genome-Wide Analysis of Nelumbo nucifera UXS Family Genes: Mediating Dwarfing and Aquatic Salinity Tolerance" Plants 15, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010116

APA StyleWang, L., Zheng, X., Liu, Y., Mao, Q., Chen, Y., Zhao, L., Cheng, X., Chen, L., & Hu, H. (2026). Genome-Wide Analysis of Nelumbo nucifera UXS Family Genes: Mediating Dwarfing and Aquatic Salinity Tolerance. Plants, 15(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010116