Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation: Mechanistic Study of the Anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berberis hemsleyana Ahrendt Extract

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Databases and Software

2.3. Extraction of B. hemsleyana Barks

2.4. LC-MS Analysis of B. hemsleyana Extract

2.5. Agar Diffusion Method

2.6. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

2.7. Membrane Permeability Assay

2.8. Biological Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.9. Prediction of Active Components and Disease Targets

2.10. Construction of Protein–Protein Interaction Network and Screening of Core Targets

2.11. KEGG Pathway Analysis and GO Enrichment Analysis

2.12. Molecular Docking

2.13. Cell Culture and Viability Assay

2.14. Measurement of Inflammatory Cytokines

2.15. Western Blot Analysis

2.16. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Component Analysis of B. hemsleyana Extract

3.2. Screening of Antibacterial Activity of B. hemsleyana Extract

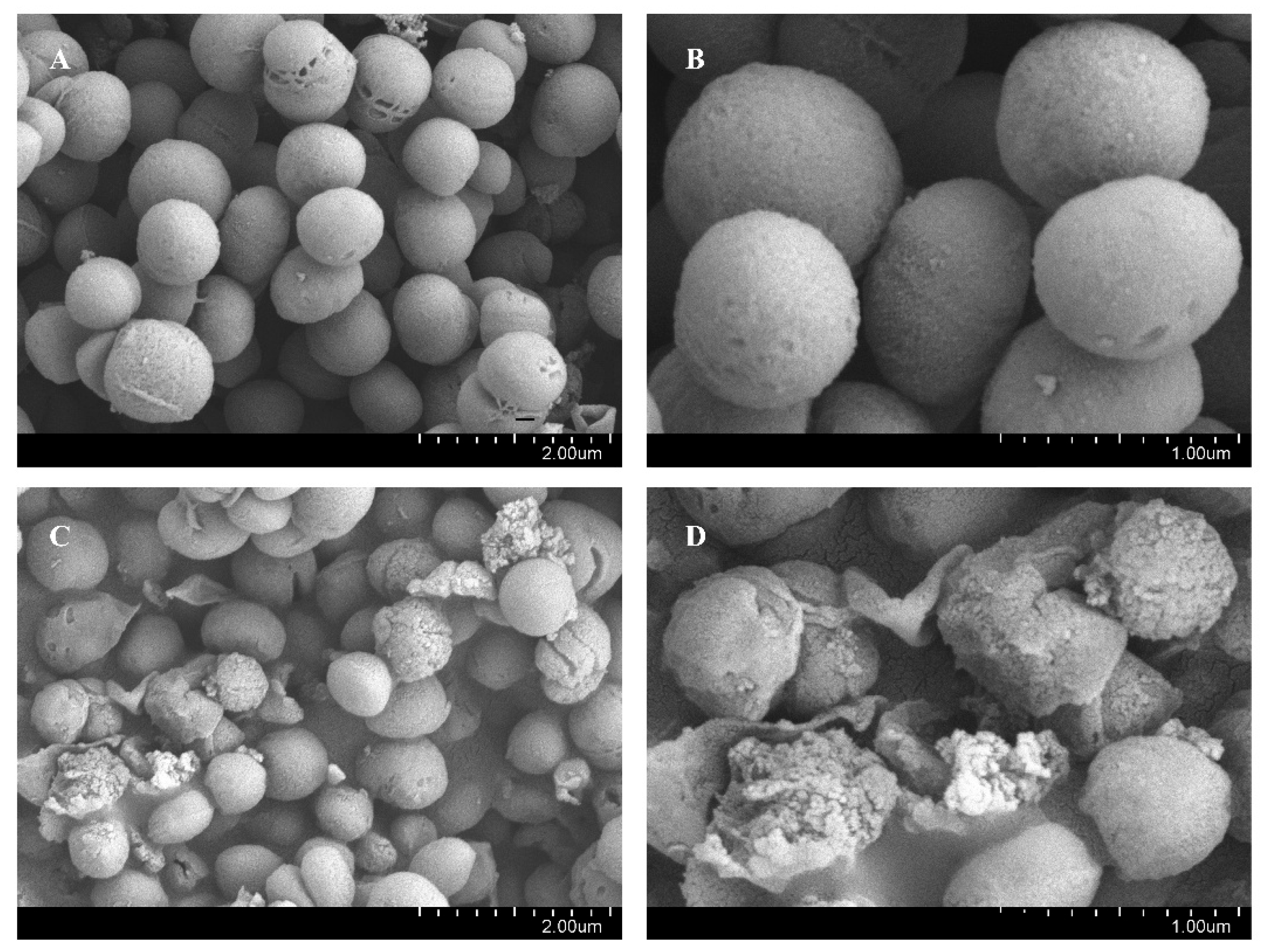

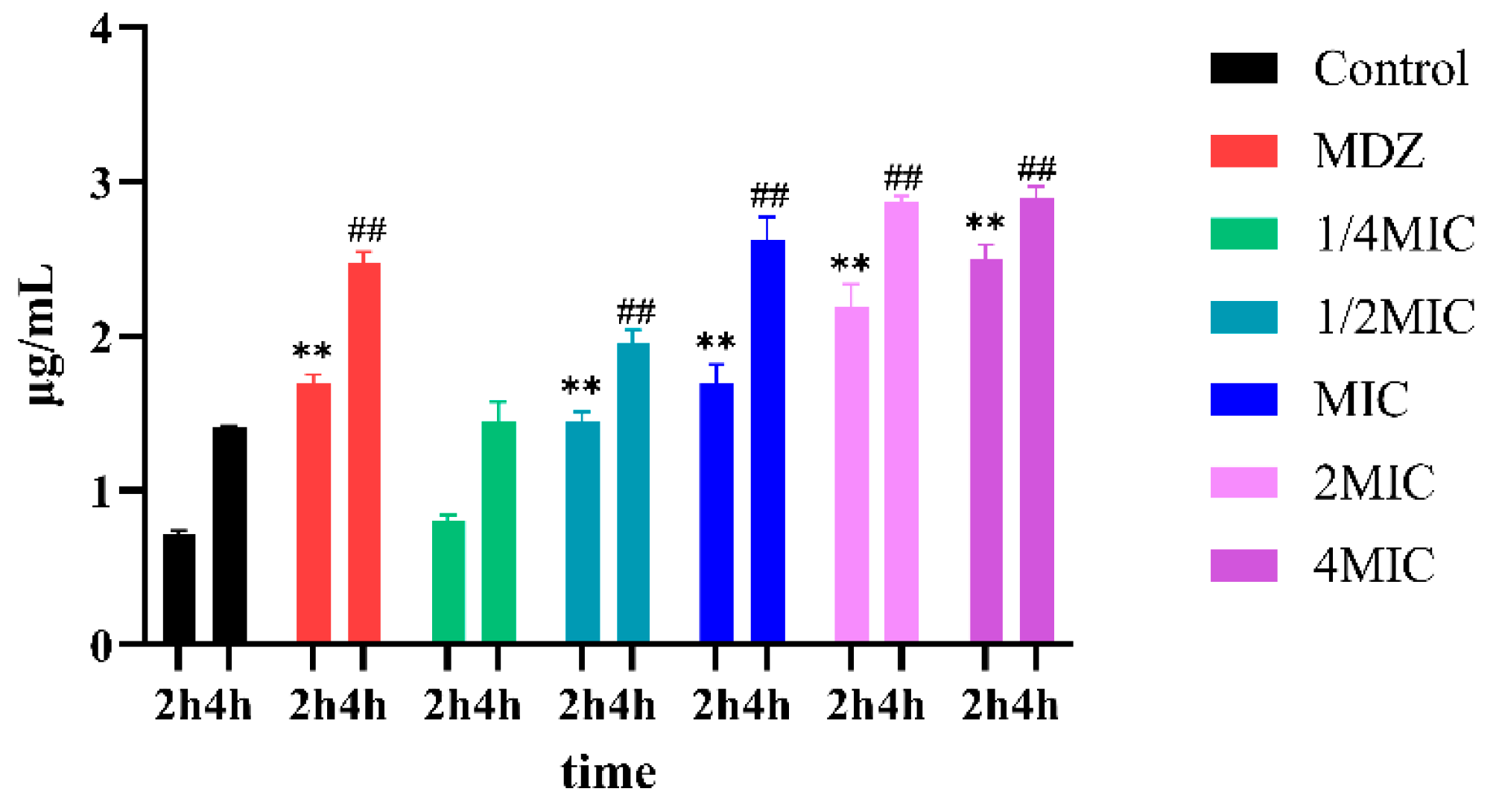

3.3. BNB Damages the Bacterial Cell Membrane of P. gingivalis

3.4. Collection of Action Targets of B. hemsleyana Extract

3.5. Screening of Key Antibacterial Targets of B. hemsleyana

3.6. Biological Function and Pathway Analysis

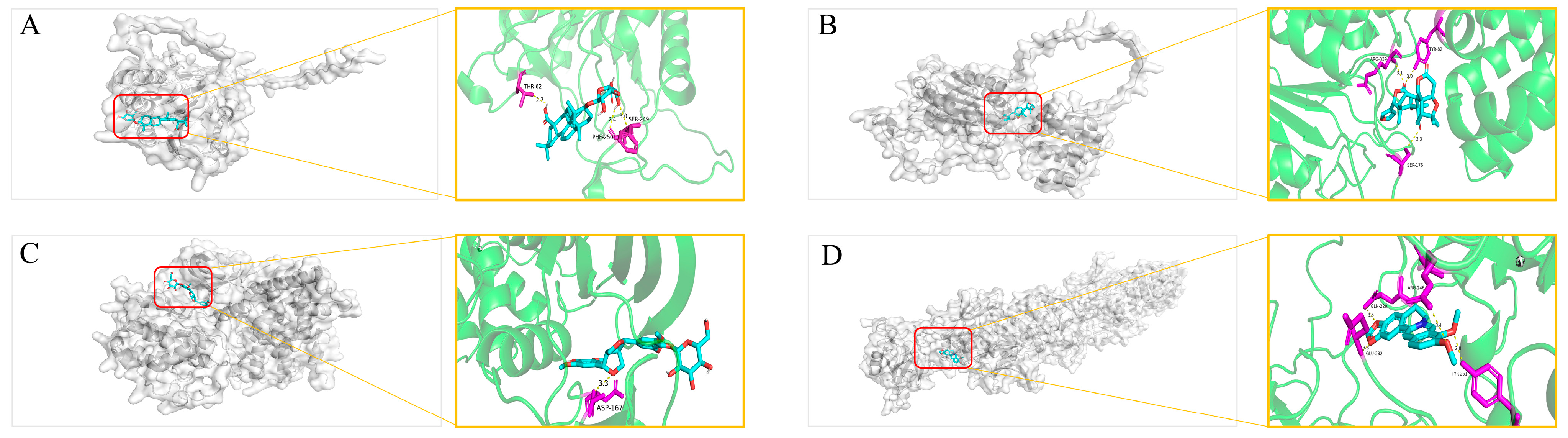

Molecular Docking Validation

3.7. BNB Reduces the Expression of Inflammatory Factors in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Cell Inflammation

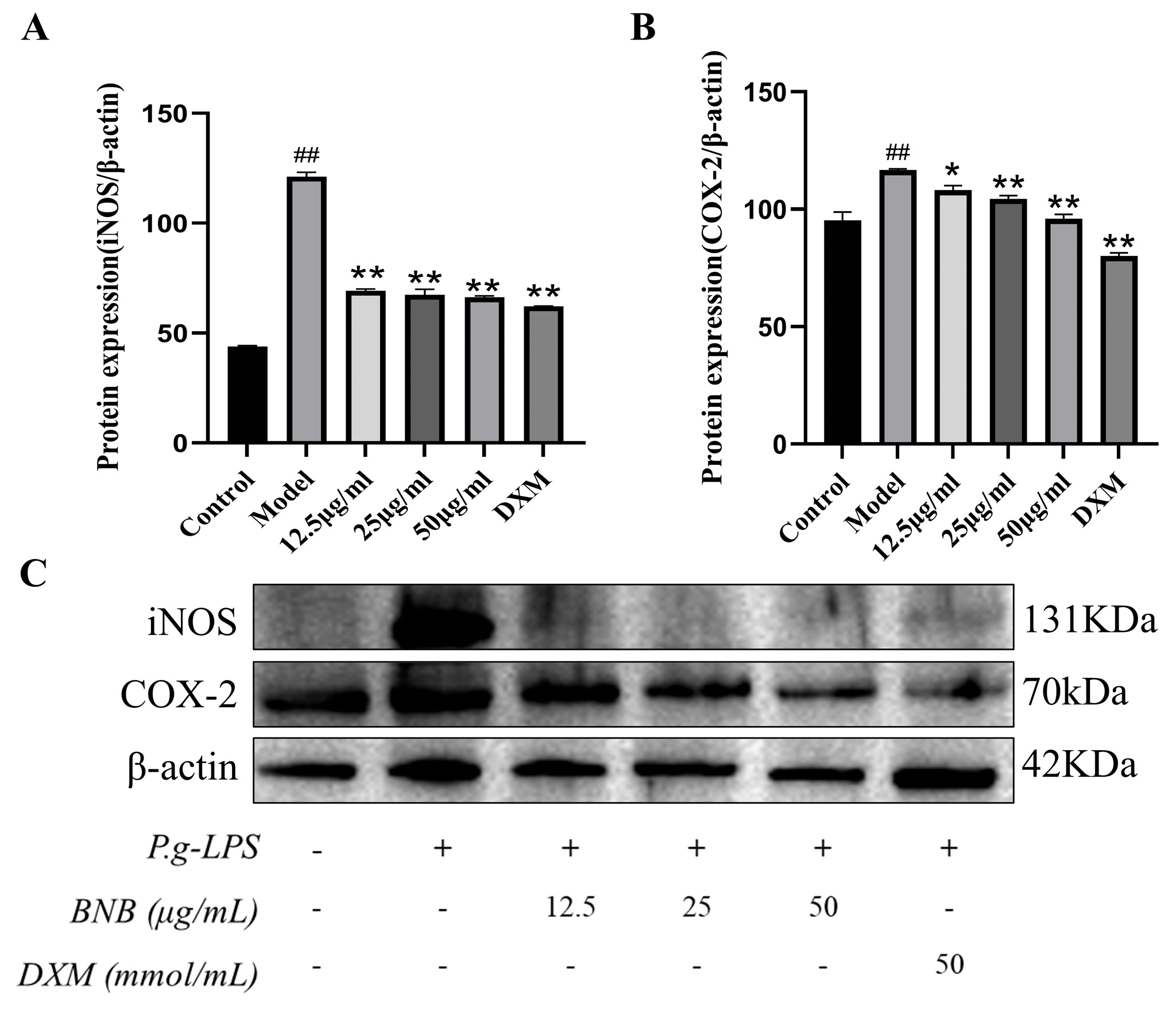

3.8. Effect of BNB on the Expression of NF-κB Pathway-Related Proteins in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, X.; You, L.; Khan, R.A.A.; Yu, Y. Phenolic Contents, Organic Acids, and the Antioxidant and Bio Activity of Wild Medicinal Berberis Plants- as Sustainable Sources of Functional Food. Molecules 2022, 27, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Qin, N.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Fan, D. Berberine regulates intestinal microbiome and metabolism homeostasis to treat ulcerative colitis. Life Sci. 2024, 338, 122385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeri, F.; Kiani, S.; Rahimi, G.; Boskabady, M.H. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects of Berberis vulgaris and its constituent berberine, experimental and clinical, a review. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 1882–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aas, J.A.; Paster, B.J.; Stokes, L.N.; Olsen, I.; Dewhirst, F.E. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5721–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassat, J.E.; Thomsen, I. Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 34, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L. Porphyromonas gingivalis. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Chirman, D.; Clark, J.R.; Xing, Y.; Hernandez Santos, H.; Vaughan, E.E.; Maresso, A.W. Vaccines against extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC): Progress and challenges. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2359691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashem, S.W.; Kaplan, D.H. Skin Immunity to Candida albicans. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayumanavan, T.; Harish, B.S.; Subashkumar, R.; Shanmugapriya, K.; Karthik, V. Streptococcus mutans biofilms in the establishment of dental caries: A review. 3 Biotech 2025, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Xue, Y.; Liu, D. Neougonin A Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Responses via Downregulation of the NF-kB Signaling Pathway in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Inflammation 2016, 39, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhang, P.; Yang, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, M. Extraction Process, Component Analysis, and In Vitro Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Total Flavonoid Extracts from Abutilon theophrasti Medic. Leaves. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 3508506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Yeom, S.H.; Park, J.E.; Kim, J.W. Effect of Ixeris dentata extract on anti-inflammatory by inhibition of Nf-kb and cytokine levels. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venanzoni, R.; Flores, G.A.; Angelini, P. Exploring Plant Extracts as a Novel Frontier in Antimicrobial Innovation: Plant Extracts and Antimicrobials. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantatto, R.R.; Chagas, A.C.d.S.; Gainza, Y.A.; Politi, F.A.S.; Mesquita, L.M.d.S.; Vilegas, W.; Bizzo, H.R.; Montanari Junior, Í.; Pietro, R.C.L.R. Acaricidal and anthelmintic action of ethanolic extract and essential oil of Achyrocline satureioides. Exp. Parasitol. 2022, 236–237, 108252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianecini, R.; Oviedo, C.; Irazu, L.; Rodríguez, M.; Galarza, P. Comparison of disk diffusion and agar dilution methods for gentamicin susceptibility testing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 91, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, C.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Li, L.; Chen, M.; Cheng, M.; et al. In Vitro Antibacterial Experiment of Fuzheng Jiedu Huayu Decoction Against Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, Y.; Huan, W.; Jie, G.; Yufang, L.I.; Qiong, Z.; Yanan, S.; Aixiang, H. Mechanism by Which Antimicrobial Peptide BCp12 Acts on the Cell Wall and Membrane of Escherichia coli Cells and Induces DNA Damage. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-N.; Li, H.-L.; Huang, J.-J.; Li, M.-J.; Liao, T.; Zu, X.-Y. Antimicrobial activities and mechanism of sturgeon spermary protein extracts against Escherichia coli. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1021338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Chang, K.; Yuan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, K.; Jiang, Y.; Tu, P.; Lu, Y.; Guo, X. Exploring the Mechanism of Hepatotoxicity Induced by Dictamnus dasycarpus Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking and Experimental Pharmacology. Molecules 2023, 28, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, F.; Hacioglu, C.; Kacar, S.; Sahinturk, V.; Kanbak, G. Betaine suppresses cell proliferation by increasing oxidative stress–mediated apoptosis and inflammation in DU-145 human prostate cancer cell line. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019, 24, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Apostichopus japonicus Extract in Porphyromonas gingivalis-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 13405–13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potempa, J. Porphyromonas Gingivalis Infections Underline Association of Periodontitis with Systemic Diseases. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 78.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Xu, Z.; Guan, J.; Zheng, J.; Hua, C.; Jiang, Q.; Li, Q.; Fan, J. Network pharmacology analysis and biological validation of molecular targets regulated by glaucocalyxin a in periodontitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 781, 152539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondino, S.; Schmidt, S.; Rolando, M.; Escoll, P.; Gomez-Valero, L.; Buchrieser, C. Legionnaires’ Disease: State of the Art Knowledge of Pathogenesis Mechanisms of Legionella. Annu. Rev. Pathol.-Mech. Dis. 2020, 15, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, N.V.; Kharat, K.R.; Kharat, A.S. Berberine from Argemone mexicana L exhibits a broadspectrum antibacterial activity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2017, 64, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Santos, A.R.D.O.D.; Carvalho, A.C.A.D.; Bechara, M.D.; Guiguer, E.L.; Goulart, R.D.A.; Vargas Sinatora, R.; Araújo, A.C.; Barbalho, S.M. Phytochemicals and Regulation of NF-kB in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Effects. Metabolites 2023, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.E.; Corsino, P.E.; Narayan, S.; Law, B.K. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors as Anticancer Therapeutics. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Effect of Bifidobacterium on osteoclasts: TNF-α/NF-κB inflammatory signal pathway-mediated mechanism. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1109296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Web Link |

|---|---|

| TCMSP (Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform) | https://www.tcmsp-e.com/ |

| ETCM (The Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicine) | http://www.tcmip.cn/ETCM/ |

| Swiss Target Prediction | https://swisstargetprediction.ch/ |

| UniProt | https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb |

| Gene Cards | https://www.genecards.org/ |

| STRING | https://cn.string-db.org/ |

| Metascape | https://metascape.org/ |

| PubChem | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| Venny 2.1.0 | https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html |

| Wei Sheng Xin Platform | http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/ |

| CB-DOCK2 | https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/php/index.php |

| MSDIAL version 4.6 software | http://prime.psc.riken.jp/ |

| Cytoscape 3.10.1 software | https://cytoscape.org/ |

| PyMOL 2.5.0 software | https://pymol.org/ |

| ImageJ software | https://imagej.net/ij/ |

| GraphPad Pism9.5 software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| No. | Compound Name | CAS | m/z | ppm | Ion Mode | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dihydroberberine | 120834-89-1 | 338.1378 | 2.6 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 2 | (R)-Fangchinoline | 33889-68-8 | 609.7138 | 3.4 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 3 | Berbamine | 478-61-5 | 609.2938 | 3.4 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 4 | Oxymatrine | 16837-52-8 | 265.19 | 4.2 | POS | Lysine alkaloids |

| 5 | (+)-Coclaurine | 2196-60-3 | 286.1429 | 3.2 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 6 | 5-Methoxydimethyltryptamine | 1019-45-0 | 219.1485 | 3.3 | POS | Tryptophan alkaloids |

| 7 | 4-Guanidinobutyric acid | 463-00-3 | 146.0926 | 1 | POS | Small peptides |

| 8 | D(+)-Pipecolinic acid | 1723-00-8 | 130.0858 | 3.6 | POS | Small peptides |

| 9 | Fraxinol | 486-28-2 | 223.0595 | 2.9 | POS | Coumarins |

| 10 | Matrine | 519-02-8 | 249.1951 | 4.3 | POS | Lysine alkaloids |

| 11 | Allomatrine | 641-39-4 | 249.1951 | 4.3 | POS | Lysine alkaloids |

| 12 | N-Formylcytisine | 53007-06-0 | 219.1123 | 2.6 | POS | Lysine alkaloids |

| 13 | Canadine | 522-97-4 | 340.1531 | 3.7 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 14 | Betaine | 107-43-7 | 118.0859 | 3.6 | POS | Small peptides |

| 15 | Tetrandrine | 518-34-3 | 623.3088 | 4.4 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 16 | Cycleanine | 518-94-5 | 623.3088 | 4.4 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 17 | (±)-Stylopine | 138791-29-4 | 324.1223 | 2.4 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 18 | 6-Hydroxycoumarin | 6093-68-1 | 161.0242 | 1.4 | NEG | Coumarins |

| 19 | 4-Hydroxycoumarin | 1076-38-6 | 161.0242 | 1.4 | NEG | Coumarins |

| 20 | trans-Ferulic acid | 537-98-4 | 193.0503 | 1.5 | NEG | Phenylpropanoids (C6-C3) |

| 21 | Isoferulic acid | 25522-33-2 | 193.0503 | 1.5 | NEG | Phenylpropanoids (C6-C3) |

| 22 | Esculetin | 305-01-1 | 177.019 | 1.6 | NEG | Coumarins |

| 23 | Daphnetin | 486-35-1 | 177.019 | 1.6 | NEG | Coumarins |

| 24 | Acanthoside B | 7374-79-0 | 579.2072 | 1.8 | NEG | Lignans |

| 25 | Eleutheroside E | 573-44-4 | 741.2602 | 1.3 | NEG | Lignans |

| 26 | Syringaresinol diglucoside | 66791-77-3 | 741.2602 | 1.3 | NEG | Lignans |

| 27 | Acanthoside D | 96038-87-8 | 741.2602 | 1.3 | NEG | Lignans |

| 28 | Liriodendrin | 573-44-4 | 741.2602 | 1.3 | NEG | Lignans |

| 29 | Trehalose | 99-20-7 | 341.1081 | 2.3 | NEG | Saccharides |

| 30 | Quercetin | 117-39-5 | 303.0492 | 2.4 | POS | Flavonoids |

| 31 | Rutin | 153-18-4 | 609.1459 | 0.3 | NEG | Flavonoids |

| 32 | Luteolin | 491-70-3 | 285.0401 | 1.2 | NEG | Flavonoids |

| 33 | Medicarpin | 33983-40-3 | 271.0958 | 2.7 | POS | Isoflavonoids |

| 34 | Ethylgallate | 831-61-8 | 197.0452 | 1.6 | NEG | Phenolic acids (C6-C1) |

| 35 | Cytisine | 485-35-8 | 191.1174 | 2.7 | POS | Nicotinic acid alkaloids |

| 36 | (+)-Isocorynoline | 475-67-2 | 340.1546 | 2.3 | NEG | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 37 | Isomagnolone | 155709-41-4 | 281.1177 | 2 | NEG | Lignans |

| 38 | (S)-Scoulerine | 6451-73-6 | 328.1537 | 1.9 | POS | Tyrosine alkaloids |

| 39 | Naringin | 10236-47-2 | 581.1844 | 3.6 | POS | Flavonoids |

| 40 | Isoformononetin | 486-63-5 | 269.0804 | 1.8 | POS | Isoflavonoids |

| 41 | Hesperetin 7-O-neohesperidoside | 13241-33-3 | 609.1811 | 2.2 | NEG | Flavonoids |

| 42 | Ursolic acid | 77-52-1 | 455.3526 | 1 | NEG | Triterpenoids |

| 43 | Tarasaponin VI | 59252-95-8 | 763.4262 | 1.5 | NEG | Triterpenoids |

| 44 | Limonin | 1180-71-8 | 471.2006 | 1.7 | POS | Triterpenoids |

| 45 | Medicagenic acid | 599-07-5 | 501.3213 | 1.7 | NEG | Triterpenoids |

| 46 | Calenduloside E | 26020-14-4 | 631.3846 | 0.9 | NEG | Triterpenoids |

| 47 | Cucurbitacin E | 18444-66-1 | 555.2939 | 4.4 | NEG | Triterpenoids |

| Strain | MIC (mg/mL) | MBC (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 6.25 ± 0.05 | 12.00 ± 0.05 |

| E. coli | 25.00 ± 0.05 | 50.00 ± 0.05 |

| P. gingivalis | 1.25 ± 0.05 | 5.00 ± 0.05 |

| S. aureus | 2.50 ± 0.05 | 5.00 ± 0.05 |

| S. mutans | 6.25 ± 0.05 | 25.00 ± 0.05 |

| Extraction Solvent | P. gingivalis Inhibition Zone (mm) |

|---|---|

| Petroleum Ether | 16.1 ± 0.30 |

| Ethyl Acetate | 22.07 ± 0.35 |

| n-Butanol | 36.2 ± 0.30 |

| Water | 26.97 ± 0.21 |

| Extraction Solvent | MIC (mg/mL) | MBC (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Petroleum Ether | 2.00 ± 0.01 | 8.00 ± 0.01 |

| Ethyl Acetate | 2.00 ± 0.01 | 4.00 ± 0.01 |

| n-Butanol | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.01 |

| Water | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 2.00 ± 0.01 |

| Gene | Corresponding Representative Active Components |

|---|---|

| CASP7 | Luteolin |

| CASP8 | Quercetin |

| CASP9 | Quercetin |

| CASP1 | Citric Acid |

| CASP3 | Citric Acid, Calenduloside E |

| BIRC5 | Palmatine, Quercetin, Luteolin |

| STAT3 | Calenduloside E, Magnoflorine |

| IL1B | Quercetin |

| STAT1 | Quercetin |

| CDK9 | Citric Acid, Dihydroberberine |

| RELA | Betaine, Matrine, Quercetin |

| BCL2 | Aesculetin |

| MCL1 | Luteolin, Acanthopanaxoside B, Liriodendrin |

| BCL2L1 | Calenduloside E, Tarasaponin VI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, G.; Gui, M.; Dong, H.; Zhuoma, D.; Li, X.; Shen, T.; Guo, H.; Yuan, R.; Li, L. Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation: Mechanistic Study of the Anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berberis hemsleyana Ahrendt Extract. Plants 2026, 15, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010115

Yang G, Gui M, Dong H, Zhuoma D, Li X, Shen T, Guo H, Yuan R, Li L. Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation: Mechanistic Study of the Anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berberis hemsleyana Ahrendt Extract. Plants. 2026; 15(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Guibin, Mingan Gui, Hai Dong, Dongzhi Zhuoma, Xuehuan Li, Tai Shen, Hao Guo, Ruiying Yuan, and Le Li. 2026. "Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation: Mechanistic Study of the Anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berberis hemsleyana Ahrendt Extract" Plants 15, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010115

APA StyleYang, G., Gui, M., Dong, H., Zhuoma, D., Li, X., Shen, T., Guo, H., Yuan, R., & Li, L. (2026). Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation: Mechanistic Study of the Anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Berberis hemsleyana Ahrendt Extract. Plants, 15(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010115