Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation and Different Phosphorus Fertilizer Levels Modulate Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization Efficiency of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in Saline-Alkali Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. AMF Status and Root Morphology Characteristics

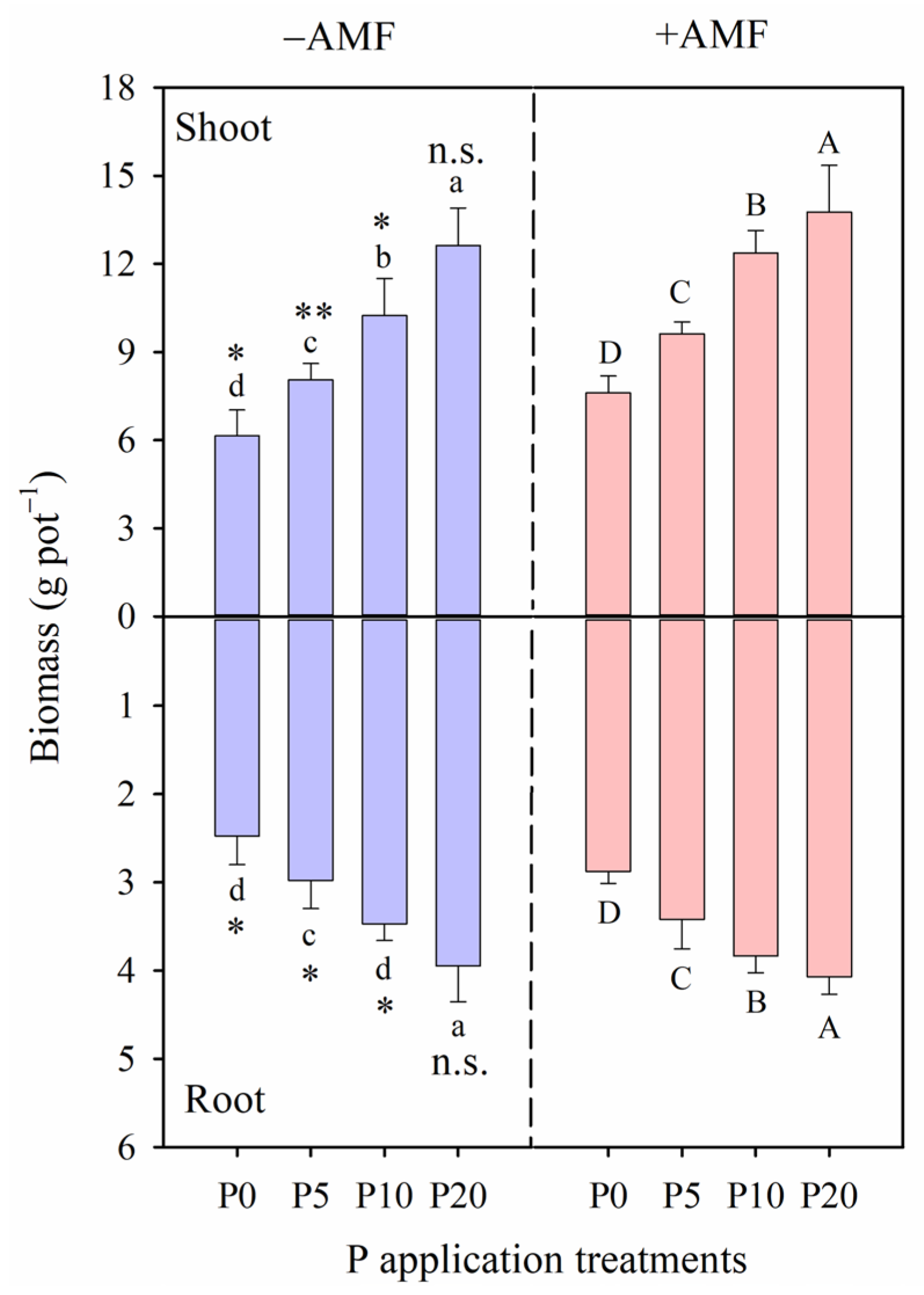

2.2. Plant Biomass and P Content, P Utilization and Acquisition Efficiency

2.3. Rhizosphere Carboxylates

2.4. Soil pH, Available P Content, Alkaline Phosphatase Activity, Microbial Biomass P and Microbial Biomass C

2.5. Correlation Analysis Between P-Utilization Efficiency and Rhizosphere Soil Variables, and Rhizosphere Carboxylates

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of AMF Inoculation on Alfalfa Growth and AMF Status Under Different P Levels

3.2. P-Acquisition Strategy of AMF Inoculation to Improve P-Use Efficiency in Alfalfa Under Low-P Supply Conditions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant and Soil Preparation

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Sample Collection

4.4. Root Characteristics and Rhizosphere Mycorrhizal Status Measurements

4.5. Plant Biomass and P Concentration Measurements

4.6. Rhizosphere Carboxylates Measurements

4.7. Soil pH, Available P Content and Alkaline Phosphatase Activity, Microbial Biomass P and Microbial Biomass C Measurements

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hammond, J.P.; White, P.J. Sucrose transport in the phloem: Integrating root responses to phosphorus starvation. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Campos, P.M.; Cornejo, P.; Rial, C.; Borie, F.; Varela, R.M.; Seguel, A.; López-Ráez, J.A. Phosphate acquisition efficiency in wheat is related to root:shoot ratio, strigolactone levels, and PHO2 regulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 5631–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.K.; Chen, R.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Li, H.; Wei, T.; Xie, W.; Fan, G.Q. Agronomic and physiological traits associated with genetic improvement of phosphorus use efficiency of wheat grown in a purple lithomorphic soil. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Lin, R.B.; Wang, Z.Y.; Mao, C.Z. Molecular mechanisms and genetic improvement of low-phosphorus tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.E.; Lynch, J.P.; Ryan, P.R.; Delhaize, E.; Smith, F.A.; Smith, S.E.; Harvey, P.R.; Ryan, M.H.; Veneklaas, E.J.; Lambers, H.; et al. Plant and microbial strategies to improve the phosphorus efficiency of agriculture. Plant Soil 2011, 349, 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honvault, N.; Houben, D.; Nobile, C.; Firmin, S.; Lambers, H.; Faucon, M.P. Tradeoffs among phosphorus-acquisition root traits of crop species for agroecological intensification. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Wu, M.M.; Zhang, Z.K.; Su, R.; He, H.H.; Zhang, X.C. The interaction of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphorus inputs on selenium uptake by alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and selenium fraction transformation in soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.H.; Pang, J.Y.; Tueux, G.; Liu, Y.F.; Shen, J.B.; Ryan, M.H.; Lambers, H.; Siddique, K.H.M. Contrasting patterns in biomass allocation, root morphology and mycorrhizal symbiosis for phosphorus acquisition among 20 chickpea genotypes with different amounts of rhizosheath carboxylates. Funct. Ecol. 2020, 34, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Y.; Chang, L.; Li, G.H.; Li, Y.F. Advances and future research in ecological stoichiometry under saline-alkali stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5475–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.D.; Zhang, S.R.; Wang, R.P.; Li, S.Y.; Liao, X.R. AM fungi and rhizobium regulate nodule growth, phosphorous (P) uptake, and soluble sugar concentration of soybeans experiencing P deficiency. J. Plant Nutr. 2016, 39, 1915–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.H.; Wu, M.M.; Guo, L.; Fan, C.B.; Zhang, Z.K.; Sui, R.; Peng, Q.; Pang, J.Y.; Lambers, H. Release of tartrate as a major carboxylate by alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) under phosphorus deficiency and the effect of soil nitrogen supply. Plant Soil 2020, 449, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.J.; Fang, Q.; Peng, S.B.; Li, Y. Genotypic variation of plant biomass under nitrogen deficiency is positively correlated with conservative economic traits in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2175–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Rengel, Z.; Cheng, L.Y.; Shen, J.B. Coupling phosphate type and placement promotes maize growth and phosphorus uptake by altering root properties and rhizosphere processes. Field Crops Res. 2024, 306, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Lone, F.A.; Bhat, R.A.; Mir, S.A.; Dar, Z.A.; Dar, S.A. Concerns and threats of contamination on aquatic ecosystems. In Bioremediation and Biotechnology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J. How understanding soil chemistry can lead to better phosphate fertilizer practice: A 68-year journey (so far). Plant Soil 2022, 476, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. Improving phosphate acquisition from soil via higher plants while approaching peak phosphorus worldwide: A critical review of current concepts and misconceptions. Plants 2024, 13, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.W.; An, Y.L.; Chen, X.P. Phosphorus fractionation related to environmental risks resulting from intensive vegetable cropping and fertilization in a subtropical region. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauro, T.P.; Nezomba, H.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Mapfumo, P. Increasing phosphorus rate alters microbial dynamics and soil available P in a Lixisol of Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjareddy, K.; Blanco, L.; Arthikala, M.K.; Affantrange, X.A.; Sánchez, F.; Lara, M. Nitrate regulates rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbiosis in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freschet, G.T.; Roumet, C.; Comas, L.H.; Weemstra, M.; Bengough, A.G.; Rewald, B.; Bardgett, R.D.; De Deyn, G.B.; Johnson, D.; Klimešová, J.; et al. Root traits as drivers of plant and ecosystem functioning: Current understanding, pitfalls and future research needs. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1123–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; Kamnev, A.A.; de-Bashan, L.E. Tricalcium phosphate is inappropriate as a universal selection factor for isolating and testing phosphate-solubilizing bacteria that enhance plant growth: A proposal for an alternative procedure. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2013, 49, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, I.; Fontaine, J.; Sahraoui, A.L.H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal responses to abiotic stresses: A review. Phytochemistry 2016, 123, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmed, N.; Zhang, L.X. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: Implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawaraya, K. Response of mycorrhizal symbiosis to phosphorus and its application for sustainable crop production and remediation of environment. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 68, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Luo, X.; Jiang, L.; Dong, R.; Siddique, K.H.M.; He, J. Legume crops use a phosphorus-mobilising strategy to adapt to low plant-available phosphorus in acidic soil in southwest China. Plant Soil Environ. 2023, 69, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Jeong, B.R.; Glick, B.R. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, and silicon to P uptake by Plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Yu, N.; Bano, S.A.; Liu, C.W.; Miller, A.J.; Cousins, D.; Zhang, X.W.; Ratet, P.; Tadege, M.; Mysore, K.S.; et al. A H+-ATPase That Energizes Nutrient Uptake during Mycorrhizal Symbioses in Rice and Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1818–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, D.; Krajinski, F.; van Tuinen, D.; Recorbet, G.; Courty, P.E. Trading on the arbuscular mycorrhiza market: From arbuscules to common mycorrhizal networks. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.H.; White, P.J.; Shen, J.B.; Lambers, H. Linking root exudation to belowground economic traits for resource acquisition. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1620–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, J.L.; Deftos, L. Calcium and Phosphate Homeostasis; Chrousos, G., Dungan, K., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyat, F.Z.; Maldani, M.; El-Guilli, M.; Nassiri, L.; Ibijbijen, J. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria isolated from phosphate solid sludge and their ability to solubilize three inorganic phosphate forms: Calcium, iron, and aluminum phosphates. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Jiang, S.S.; Deng, Y.; Christie, P.; Murray, P.J.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, J.L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soil and roots respond differently to phosphorus inputs in an intensively managed calcareous agricultural soil. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Zhang, Z.K.; Chang, C.; Peng, Q.; Cheng, X.; Pang, J.Y.; He, H.H.; Lambers, H. Interactive effects of phosphorus fertilization and salinity on plant growth, phosphorus and sodium status, and tartrate exudation by roots of two alfalfa cultivars. Ann. Bot. 2022, 129, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.C.; Guo, D.D.; Zhang, H.B.; Che, Y.H.; Li, Y.Y.; Tian, B.; Wang, Z.H.; Sun, G.Y.; Zhang, H.H. Physiological and comparative transcriptome analysis of leaf response and physiological adaption to saline alkali stress across pH values in alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Li, A.; Nie, R.N.; Wu, C.X.; Ji, X.Y.; Tang, J.L.; Zhang, J.P. Differential Strategies of Two Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Varieties in the Protection of Lycium ruthenicum under Saline–Alkaline Stress. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.H.; Li, H.B.; Shen, Q.; Tang, X.M.; Xiong, C.Y.; Li, H.G.; Pang, J.Y.; Ryan, M.H.; Lambers, H.; Shen, J.B. Tradeoffs among root morphology, exudation and mycorrhizal symbioses for phosphorus-acquisition strategies of 16 crop species. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.W.; Chen, M.; Tian, F.P.; Yao, R.; Qin, N.N.; Wu, W.H.; Turner, N.C.; Li, F.M.; Du, Y.L. Root morphology, exudate patterns, and mycorrhizal symbiosis are determinants to improve phosphorus acquisition in alfalfa. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 3543–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, T.Y.; Wu, S.H.; Wen, M.X.; Lu, L.M.; Ke, F.Z.; Wu, Q.S. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on rhizosphere organic acid content and microbial activity of trifoliate orange under different low P conditions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2019, 65, 2029–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, M.; Meena, V.S.; Mishra, P.K.; Rakshit, A.; Choudhary, M.; Yadav, P.R.; Rana, K.; Bisht, J.K. Arbuscular mycorrhiza: A viable strategy for soil nutrient loss reduction. Arch. Microbiol. 2019, 201, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grman, E. Plant species differ in their ability to reduce allocation to non-beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Ecology 2012, 93, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.G.; Chai, X.F.; Wang, X.H.; Batchelor, W.D.; Kafle, A.; Feng, G. Indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi play a role in phosphorus depletion in organic manure amended high fertility soil. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 3051–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, I.; Konieczny, A. Effect of mycorrhiza on yield and quality of lettuce grown on medium with different levels of phosphorus and selenium. Agric. Food Sci. 2019, 28, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, D.A.; Flynn, D.; Caruso, T. Improving phosphorus sustainability in intensively managed grasslands: The potential role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, N.C.; Wilson, G.W.T.; Wilson, J.A.; Miller, R.M.; Bowker, M.A. Mycorrhizal phenotypes and the law of the minimum. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.H.; Dong, Z.G.; Peng, Q.; Wang, X.; Fan, C.B.; Zhang, X.C. Impacts of coal fly ash on plant growth and accumulation of essential nutrients and trace elements by alfalfa (Medicago sativa) grown in a loessial soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.P. Root phenotypes for improved nutrient capture: An underexploited opportunity for global agriculture. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Batool, F.; Muhammad, M.; Zaman, W.; Mikhlef, R.M.; Qaddoori, S.M.; Ullah, S.; Abdi, G.; Saqib, S. Unveiling the complex molecular dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizae: A comprehensive exploration and future perspectives in harnessing phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms for sustainable progress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 219, 105633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Raven, J.A.; Shaver, G.R.; Smith, S.E. Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Jakobsen, I.; Grønlund, M.; Smith, F.A. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant phosphorus nutrition: Interactions between pathways of phosphorus uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots have important implications for understanding and manipulating plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts-Williams, S.J.; Smith, F.A.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Patti, A.F.; Cavagnaro, T.R. How important is the mycorrhizal pathway for plant Zn uptake? Plant Soil 2015, 390, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkelaker, B.; Römheld, V.; Marschner, H. Citric acid excretion and precipitation of calcium citrate in the rhizosphere of white lupin (Lupinus albus L.). Plant Cell Environ. 1989, 12, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Dennis, P.G.; Owen, A.G.; van Hees, P.A.W. Organic acid behavior in soils–misconceptions and knowledge gaps. Plant Soil 2003, 248, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Sato, H.; Tanabe, A.S.; Hidaka, A.; Toju, H. Mycorrhizal fungi mediate the direction and strength of plant–soil feedbacks differently between arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal communities. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J. The effects of pH on phosphate uptake from the soil. Plant Soil 2017, 410, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A.; Smith, F.A. Nitrogen assimilation and transport in vascular land plants in relation to intracellular pH regulation. New Phytol. 1976, 76, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.S.; Gregory, P.J.; Wood, M.; Read, D.; Buresh, R.J. Phosphatase activity and organic acids in the rhizosphere of potential agroforestry species and maize. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.Y.; Bansal, R.; Zhao, H.X.; Bohuon, E.; Lambers, H.; Ryan, M.H.; Ranathunge, K.; Siddique, K.H.M. The carboxylate-releasing phosphorus-mobilizing strategy can be proxied by foliar manganese concentration in a large set of chickpea germplasm under low phosphorus supply. New Phytol. 2018, 219, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A.; Lambers, H.; Smith, S.E.; Westoby, M. Costs of acquiring phosphorus by vascular land plants: Patterns and implications for plant coexistence. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rillig, M.C.; Mummey, D.L. Mycorrhizas and soil structure. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Jiang, N.; Condron, L.M.; Dunfield, K.E.; Chen, Z.H.; Wang, J.K.; Chen, L.J. Soil alkaline phosphatase activity and bacterial phoD gene abundance and diversity under long-term nitrogen and manure inputs. Geoderma 2019, 349, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.Z.; Liu, X.J.; Ouyang, J.H.; Tu, X.J.; Song, W.Z.; Cao, W.; Tao, Q.B.; Sun, J. Effects of biochar and phosphorus fertilizer combination on the physiological growth characteristics of alfalfa in saline-alkali soil of the Yellow River Delta. Chin. J. Grassl. 2024, 46, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.Z.; Zhang, X.; Hou, P.X.; Ouyang, J.H.; Rakotoson, T.; Zheng, C.C.; Sun, J. Biochar amendment enhances water use efficiency in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) under partial root-zone drying irrigation by modulating abscisic acid signaling and photosynthetic performance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 238, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M.E.; Miller, W.P. Cation Exchange Capacity and Exchange Coefficients; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., Sumner, M.E., Bartels, J.M., Bigham, J.M., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stüeken, E.E.; de Castro, M.; Krotz, L.; Brodie, C.; Iammarino, M.; Giazzi, G. Optimized switch-over between CHNS abundance and CNS isotope ratio analyses by elemental analyzer-isotope ratio mass spectrometry: Application to six geological reference materials. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 34, e8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walinga, I.; Kithome, M.; Novozamsky, I.; Houba, V.J.G.; Van der Lee, J.J. Spectrophotometric determination of organic carbon in soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1992, 23, 1935–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, K.; Datta, A.; Jat, H.S.; Choudhary, M.; Sharma, P.C.; Jat, M.L. Assessing the availability of potassium and its quantity-intensity relations under long term conservation agriculture based cereal systems in North-West India. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 228, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Liu, R.J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in saline-alkaline soils of Yellow River Delta. Mycosystema 2002, 9, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendzemo, V.W.; Kuyper, T.W.; Matusova, R.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; van Ast, A. Colonizatio by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi of sorghum leads to reduced germination and subsequent attachment and emergence of Striga hermonthica. Plant Signal. Behav. 2007, 2, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.Z.; Hou, P.X.; Zheng, C.C.; Yang, X.C.; Tao, Q.B.; Sun, J. Wheat Straw Biochar Amendment Increases Salinity Stress Tolerance in Alfalfa Seedlings by Modulating Physiological and Biochemical Responses. Plants 2025, 14, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle, T.P.; Miller, M.H.; Evans, D.G.; Fairchild, G.L.; Swan, J.A. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular—Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdemann, J.W.; Nicolson, T.H. Spores of micorrhizal Endogone species extracted from soil by wet sieving and decanting. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethlenfalvay, G.J.; Ames, R.N. Comparison of two methods for quantifying extraradical mycelium of vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1987, 51, 834–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.Z.; Xu, Y.Q.; Meng, B.; Loik, M.E.; Ma, J.Y.; Sun, W. Nitrogen Addition Increases the Sensitivity of Photosynthesis to Drought and Re-watering Differentially in C3 Versus C4 Grass Species. Fron. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, M.L.R. Soil Chemical Analysis: Advanced Course: A Manual of Methods Useful for Instruction and Research in Soil Chemistry, Physical Chemistry of Soils, Soil Fertility, and Soil Genesis; University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries Parallel Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthray, G.R. An improved reversed-phase liquid chromatographic method for the analysis of low-molecular mass organic acids in plant root exudates. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1011, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeri, N.K.; Lambers, H.; Tibbett, M.; Ryan, M.H. Moderating mycorrhizas: Arbuscular mycorrhizas modify rhizosphere chemistry and maintain plant phosphorus status within narrow boundaries. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, C.V.; Watanabe, F.S.; Dean, L.A. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, USA, 1954; Volume 939, pp. 1–19.

- Watanabe, F.S.; Olsen, S.R. Test of an ascorbic acid method for determining phosphorus in water and NaHCO3 extracts from soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1965, 29, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöergensen, R.G. The fumigation-extraction method to estimate soil microbial biomass: Calibration of the kEC value. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.A.; Bååth, E.; Jakobsen, I.; Söderström, B. The use of phospholipid and neutral lipid fatty acids to estimate biomass of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soil. Mycol. Res. 1995, 99, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | AMF Colonization Rate (%) | Spore Density (No. g−1) | Hyphal Length (m g−1) | Mycorrhizal Contribution (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | −AMF | - | - | - | 21.17 ± 4.02 AB | ||||

| +AMF | 60.36 ± 3.78 B | 40.32 ± 2.34 B | 2.52 ± 0.21 B | ||||||

| P5 | −AMF | - | - | - | 23.58 ± 2.51 A | ||||

| +AMF | 69.62 ± 4.52 A | 52.75 ± 4.84 A | 3.01 ± 0.19 A | ||||||

| P10 | −AMF | - | - | - | 18.37 ± 3.30 B | ||||

| +AMF | 62.42 ± 7.66 AB | 48.89 ± 3.46 A | 2.62 ± 0.17 B | ||||||

| P20 | −AMF | - | - | - | 8.37 ± 4.57 C | ||||

| +AMF | 52.34 ± 5.38 C | 35.07 ± 2.85 C | 1.85 ± 0.15 C | ||||||

| Significance | |||||||||

| F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | ||

| AMF | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| P | 8.26 | 0.002 ** | 26.11 | <0.001 *** | 35.77 | <0.001 *** | 16.46 | <0.001 *** | |

| AMF × P | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Treatment | Total Root Length (m) | Root Diameter (mm) | Root Surface Area (cm2) | Specific Root Length (m g−1) | Root/Shoot Ratio (None) | Total Biomass (g Pot−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | −AMF | 11.82 ± 0.88 d ** | 1.95 ± 0.13 d n.s. | 118.22 ± 17.01 d * | 4.83 ± 0.54 a n.s. | 0.41 ± 0.08 a n.s. | 8.62 ± 0.99 d ** | ||||||

| +AMF | 13.54 ± 0.69 C | 1.93 ± 0.05 D | 147.34 ± 18.53 D | 4.72 ± 0.38 A | 0.38 ± 0.05 A | 10.48 ± 0.51 D | |||||||

| P5 | −AMF | 13.78 ± 0.57 c ** | 2.16 ± 0.16 c n.s. | 152.84 ± 11.50 c * | 4.66 ± 0.43 ab n.s. | 0.37 ± 0.02 ab n.s. | 11.03 ± 0.86 c *** | ||||||

| +AMF | 14.90 ± 0.98 B | 2.13 ± 0.09 C | 176.76 ± 16.31 C | 4.39 ± 0.54 AB | 0.36 ± 0.05 B | 13.04 ± 0.39 C | |||||||

| P10 | −AMF | 15.71 ± 0.31 b * | 2.67 ± 0.10 b * | 225.57 ± 20.01 b n.s. | 4.54 ± 0.24 b n.s. | 0.34 ± 0.05 ab n.s. | 13.71 ± 1.20 b ** | ||||||

| +AMF | 16.62 ± 0.56 A | 2.56 ± 0.09 B | 247.22 ± 29.77 B | 4.35 ± 0.35 BC | 0.31 ± 0.02 C | 16.20 ± 0.82 B | |||||||

| P20 | −AMF | 17.56 ± 0.80 a n.s. | 3.40 ± 0.19 a * | 318.56±32.84 a n.s. | 4.49 ± 0.55 c *** | 0.32 ± 0.04 b n.s. | 16.57 ± 1.31 a * | ||||||

| +AMF | 16.86 ± 0.56 A | 3.14 ± 0.14 A | 307.42 ± 18.65 A | 4.14 ± 0.15 C | 0.30 ± 0.02 C | 17.84 ± 1.65 A | |||||||

| Significance | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| AMF | 12.14 | 0.001 *** | 7.71 | 0.009 ** | 5.39 | 0.027 * | 9.50 | 0.004 ** | 2.45 | 0.127 n.s. | 33.46 | <0.001 *** | |

| P | 84.53 | <0.001 *** | 227.19 | <0.001 *** | 137.45 | <0.001 *** | 6.98 | 0.001 *** | 6.91 | 0.001 *** | 103.05 | <0.001 *** | |

| AMF × P | 5.64 | 0.003 ** | 2.03 | 0.129 n.s. | 1.79 | 0.170 n.s. | 0.47 | 0.703 n.s. | 0.07 | 0.973 n.s. | 0.584 | 0.630 n.s. | |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) | Phosphorus (P) | AMF × P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Shoot biomass | 25.02 | <0.001 *** | 77.54 | <0.001 *** | 0.42 | 0.738 n.s. |

| Root biomass | 14.43 | 0.001 ** | 43.41 | <0.001 *** | 0.66 | 0.582 n.s. |

| Shoot P content | 9.42 | 0.004 *** | 60.76 | <0.001 *** | 1.05 | 0.386 n.s. |

| Root P content | 16.75 | <0.001 *** | 82.50 | <0.001 *** | 1.76 | 0.175 n.s. |

| Plant P content | 55.64 | <0.001 *** | 226.37 | <0.001 *** | 1.00 | 0.405 n.s. |

| P-utilization efficiency | 20.79 | <0.001 *** | 92.87 | <0.001 *** | 3.21 | 0.036 * |

| P-acquisition efficiency | 10.89 | 0.003 ** | 20.47 | <0.001 *** | 2.00 | 0.157 n.s. |

| Citrate | 51.35 | <0.001 *** | 38.50 | <0.001 *** | 0.42 | 0.742 n.s. |

| Acetate | 145.34 | <0.001 *** | 82.28 | <0.001 *** | 1.59 | 0.313 n.s. |

| Malonate | 8.22 | 0.007 ** | 36.19 | <0.001 *** | 1.30 | 0.290 n.s. |

| Malate | 25.47 | <0.001 *** | 6.72 | 0.002 ** | 1.05 | 0.406 n.s. |

| Tartrate | 114.03 | <0.001 *** | 35.54 | <0.001 *** | 1.43 | 0.251 n.s. |

| Rhizosphere carboxylates | 191.21 | <0.001 *** | 96.48 | <0.001 *** | 1.28 | 0.300 n.s. |

| Rhizosphere soil | ||||||

| pH | 6.09 | 0.019 * | 9.08 | <0.001 *** | 0.66 | 0.583 n.s. |

| AP | 7.34 | 0.011 * | 130.56 | <0.001 *** | 1.43 | 0.253 n.s. |

| ALP | 27.06 | <0.001 *** | 134.93 | <0.001 *** | 1.67 | 0.193 n.s. |

| MBP | 247.04 | <0.001 *** | 96.84 | <0.001 *** | 1.33 | 0.281 n.s. |

| MBC | 27.55 | <0.001 *** | 67.02 | <0.001 *** | 1.03 | 0.393 n.s. |

| Bulk soil | ||||||

| pH | 4.14 | 0.050 * | 6.79 | 0.001 ** | 0.35 | 0.790 n.s. |

| AP | 10.69 | 0.003 ** | 117.06 | <0.001 *** | 1.11 | 0.359 n.s. |

| ALP | 29.77 | <0.001 *** | 70.43 | <0.001 *** | 0.47 | 0.709 n.s. |

| MBP | 38.38 | <0.001 *** | 107.81 | <0.001 *** | 0.33 | 0.805 n.s. |

| MBC | 44.52 | <0.001 *** | 62.86 | <0.001 *** | 0.31 | 0.821 n.s. |

| Factor | Soil |

|---|---|

| Clay (<0.002 mm), % | 4 |

| Silt (0.05–0.002 mm), % | 70 |

| Sand (2–0.05 mm), % | 26 |

| pH | 8.97 |

| EC, μS cm−1 | 1044.68 |

| CEC, cmol + kg−1 | 23.05 |

| Total C, g kg−1 | 18.38 |

| Total N, mg kg−1 | 251.60 |

| Total K, mg kg−1 | 19.38 |

| Total P, mg kg−1 | 547.76 |

| Available P, mg kg−1 | 3.76 |

| Organic matter, g kg−1 | 5.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhong, S.; Hou, P.; Yu, M.; Cao, W.; Tu, X.; Ma, X.; Miao, F.; Tao, Q.; Sun, J.; Jia, W. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation and Different Phosphorus Fertilizer Levels Modulate Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization Efficiency of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in Saline-Alkali Soil. Plants 2026, 15, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010114

Zhong S, Hou P, Yu M, Cao W, Tu X, Ma X, Miao F, Tao Q, Sun J, Jia W. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation and Different Phosphorus Fertilizer Levels Modulate Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization Efficiency of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in Saline-Alkali Soil. Plants. 2026; 15(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Shangzhi, Pengxin Hou, Mingliu Yu, Wei Cao, Xiangjian Tu, Xiaotong Ma, Fuhong Miao, Qibo Tao, Juan Sun, and Wenke Jia. 2026. "Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation and Different Phosphorus Fertilizer Levels Modulate Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization Efficiency of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in Saline-Alkali Soil" Plants 15, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010114

APA StyleZhong, S., Hou, P., Yu, M., Cao, W., Tu, X., Ma, X., Miao, F., Tao, Q., Sun, J., & Jia, W. (2026). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Inoculation and Different Phosphorus Fertilizer Levels Modulate Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization Efficiency of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in Saline-Alkali Soil. Plants, 15(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010114