Integrative Transcriptomic and Evolutionary Analysis of Drought and Heat Stress Responses in Solanum tuberosum and Solanum lycopersicum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

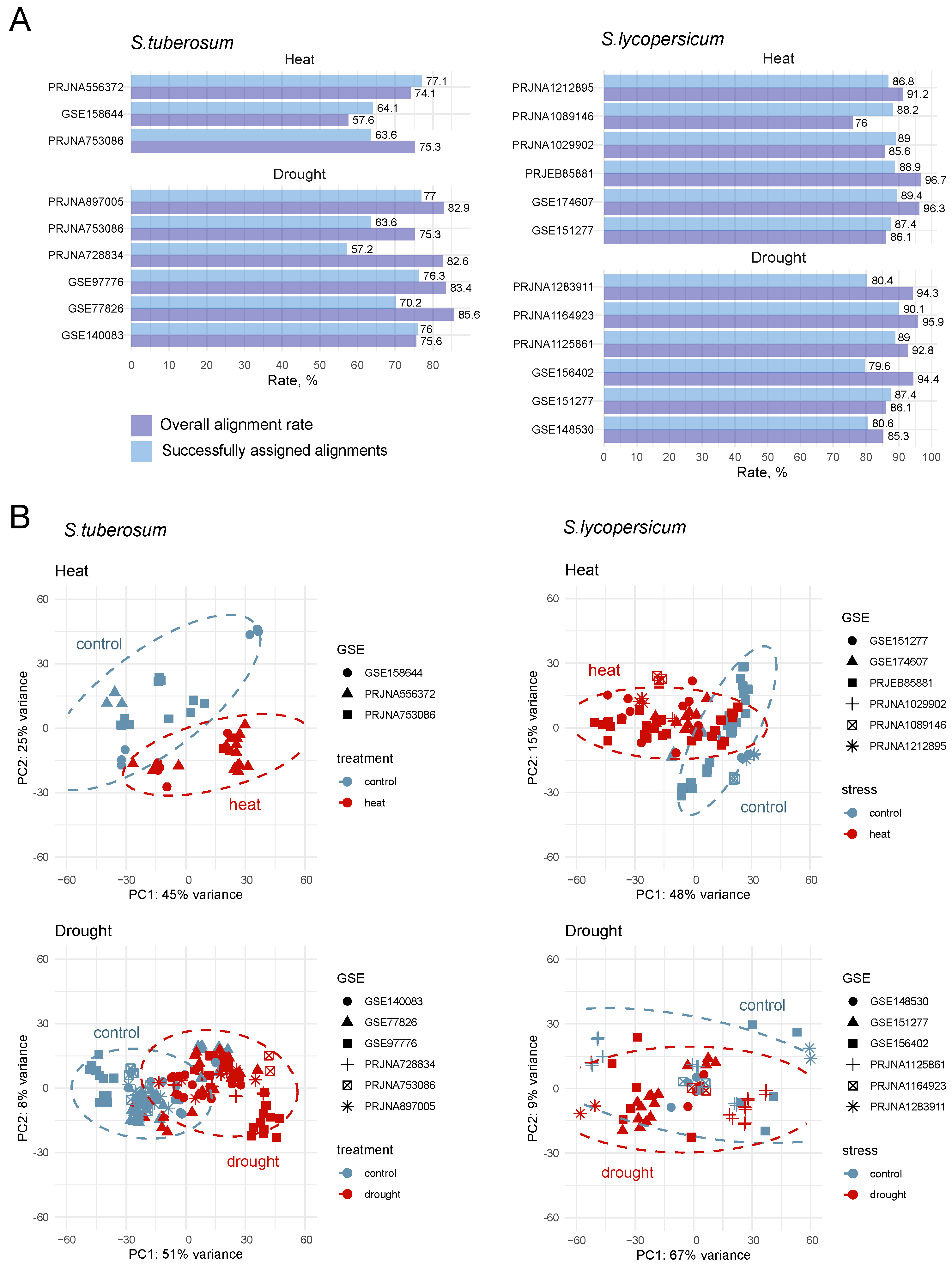

2.1. Search and Selection of Relevant Transcriptomic Experiments for Analysis

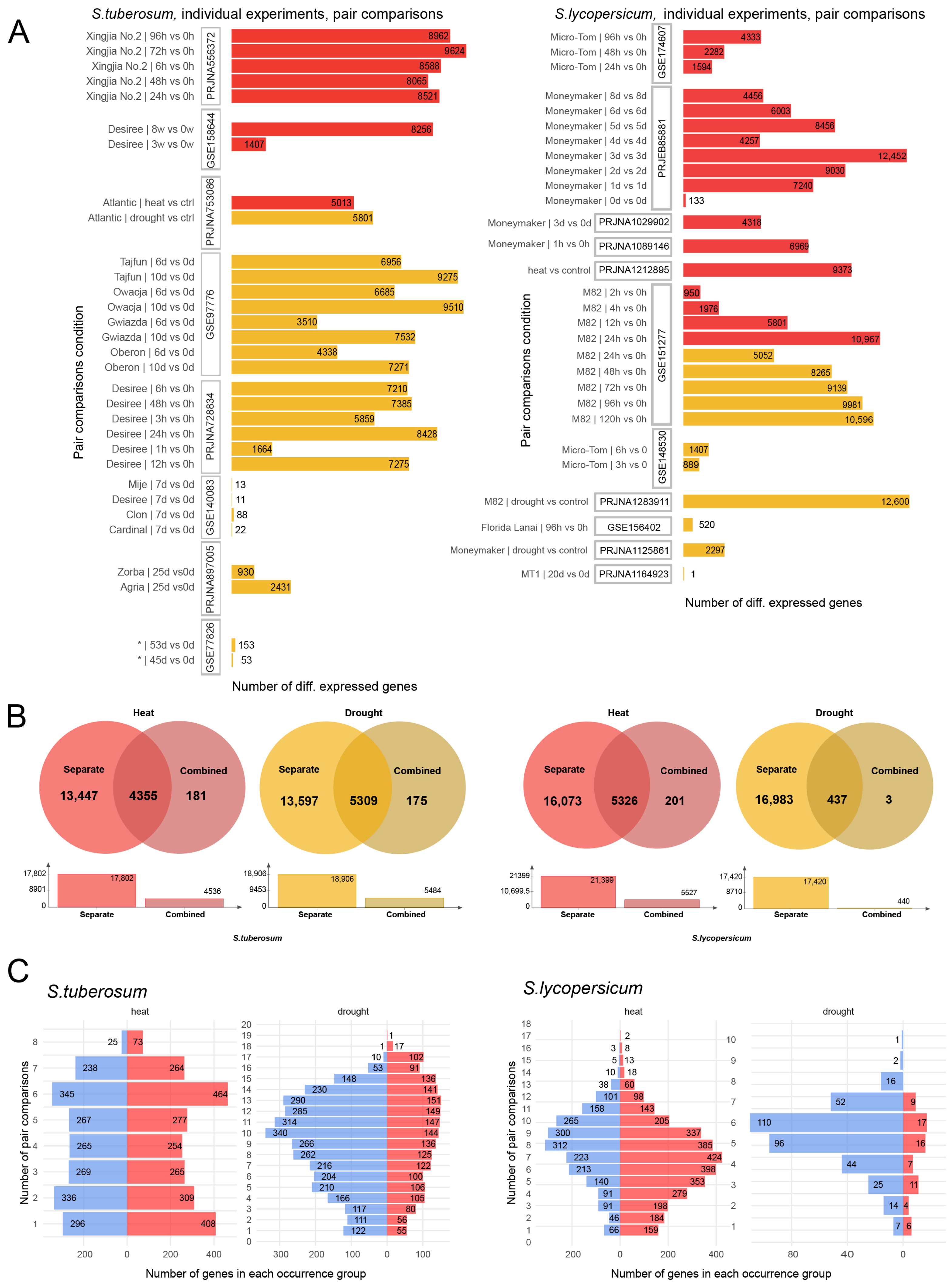

2.2. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

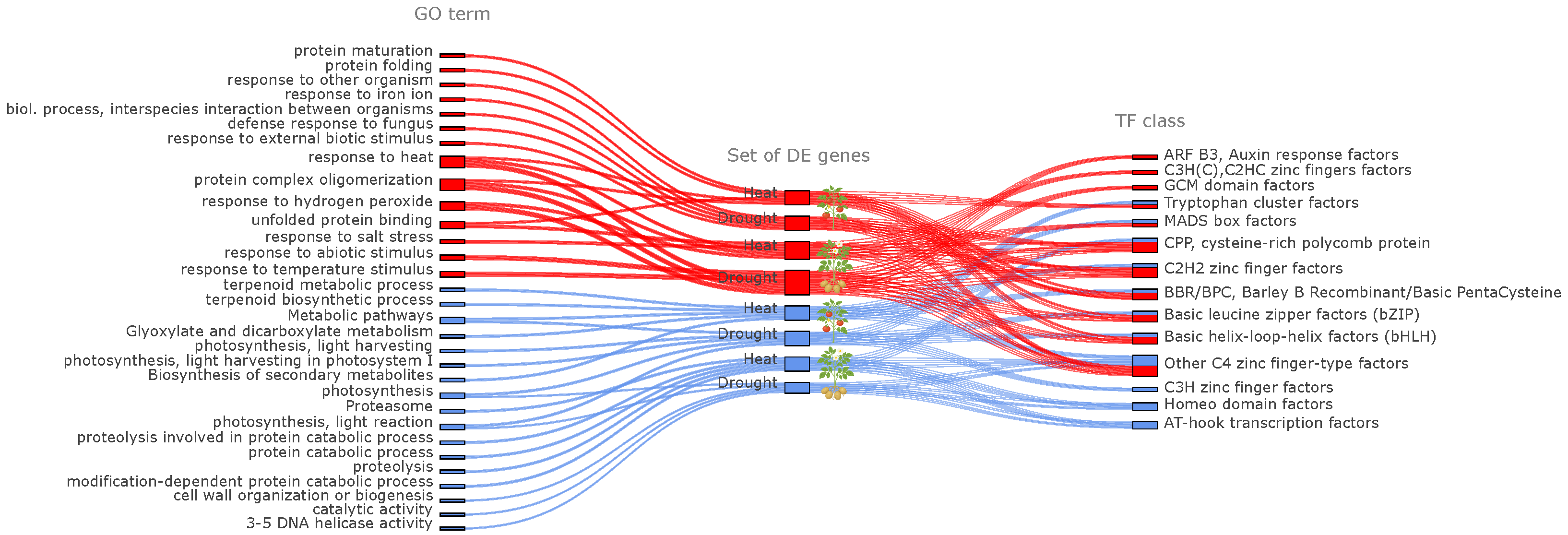

2.3. Functional and Regulatory Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes Under Drought and Heat Stress

2.3.1. Functional Annotation of Differentially Expressed Genes

2.3.2. Identification of Regulatory Motifs and Transcription Factor Classes

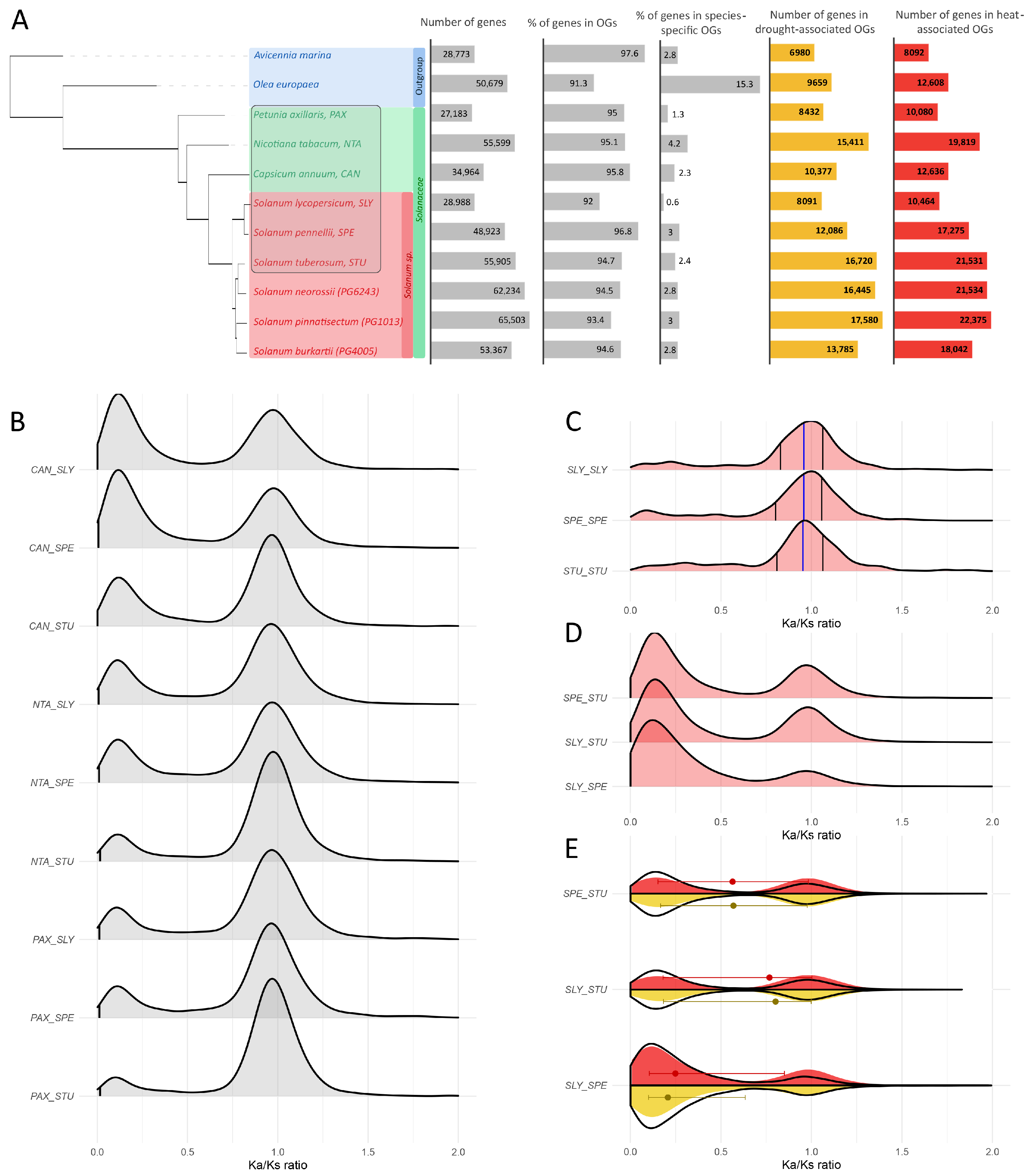

2.4. Comparative Genomic and Orthogroup Analysis of Solanaceae Species

2.4.1. Identification of Orthologous Groups

2.4.2. Evolutionary Dynamics and Selective Constraints in Orthologous Genes

2.5. Gene Network Analysis of Stress Response

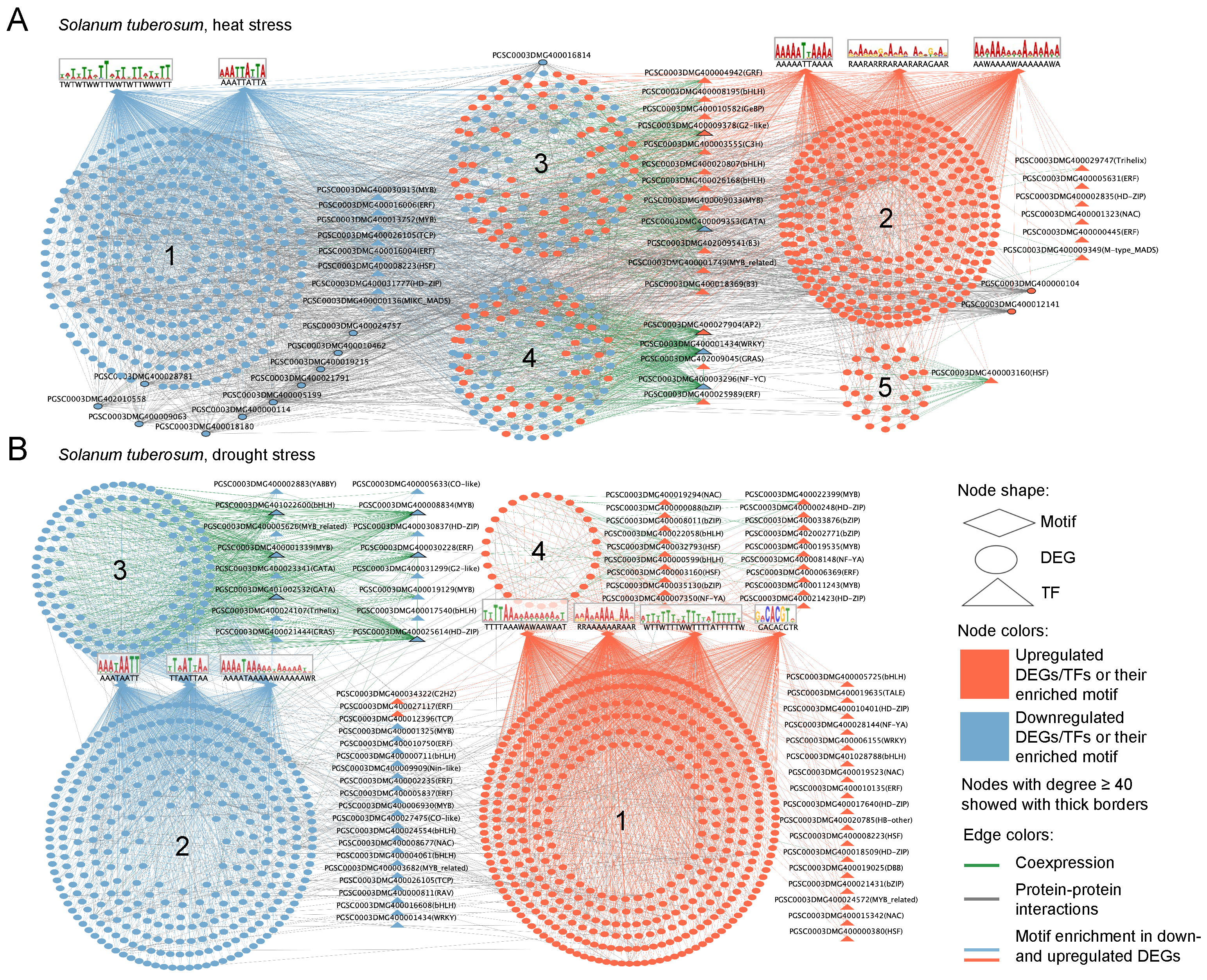

2.5.1. Solanum tuberosum

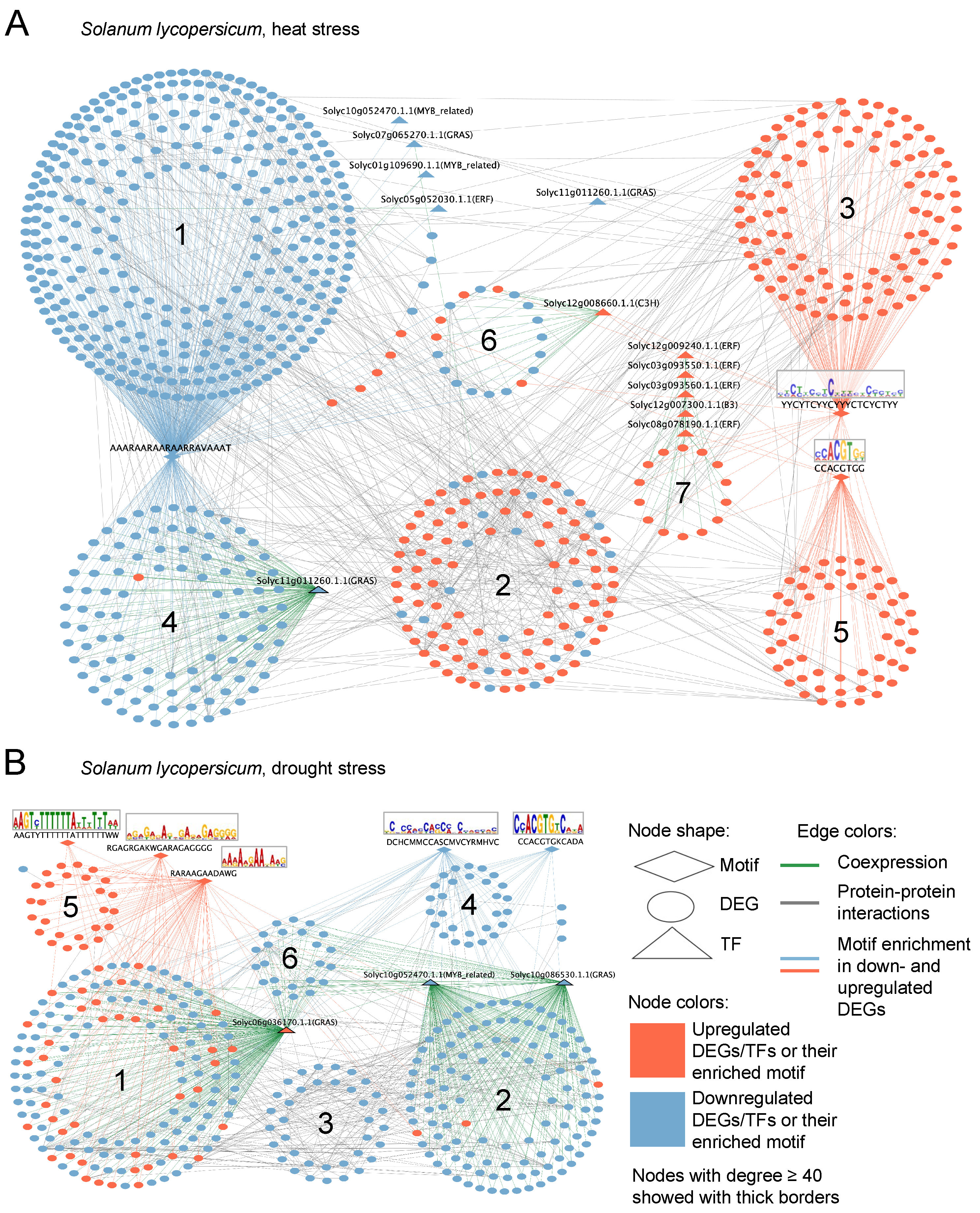

2.5.2. Solanum lycopersicum

2.5.3. Orthologs in Reconstructed Gene Networks

- Heat shock proteins: three heat shock cognate 70 kDa proteins, two heat shock protein 83, and two additional heat shock proteins, which likely contribute to protein folding and protection under elevated temperature.

- Transcriptional and RNA metabolism regulators: two DNA-directed RNA polymerases, a serine/arginine-rich splicing factor, a DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase, a peptidyl–prolyl isomerase, and an AAR2 protein family member, indicating active post-transcriptional control of gene expression during heat stress.

- Signaling components: PERK1 kinase, WRKY transcription factor C, ethylene response factor ERF4, and a calmodulin-binding protein, reflecting the integration of hormonal and calcium-dependent signaling cascades in heat adaptation.

- Protein metabolism genes: ubiquitin carrier protein, RING zinc finger protein, cysteine protease, protein phosphatase, heat shock protein DnaJ, protein translocase, and transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase, suggesting a reduction in protein turnover and degradation.

- Other metabolic processes: S-adenosyl-methionine-sterol-C-methyltransferase, delta-8 sphingolipid desaturase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, glycerate dehydrogenase, amino acid transporter, 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate phosphatase, and starch synthase VI, which may indicate a shift in primary metabolism toward energy conservation.

- Organelle-associated proteins: chloroplast ferredoxin I, protein of the chloroplast import apparatus 2, DNA-directed RNA polymerase 2B, and mitochondrial small heat shock protein, pointing to altered plastid and mitochondrial functions under prolonged heat exposure.

- Photosynthesis- and chloroplast-related genes: two chlorophyll a/b binding proteins, thylakoid soluble phosphoprotein, tetrapyrrole-binding protein, chloroplast fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase I, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, PTAC16, and nitrite reductase, reflecting the suppression of photosynthetic activity under drought stress.

- Cell wall and extracellular matrix metabolism: arabinogalactan peptide 14, methionine-rich arabinogalactan, pectate lyase, and glycosyltransferase, suggesting the remodeling of the cell wall to prevent water loss.

- Signaling and regulatory components: serine/threonine protein kinase, P21-rho-binding domain-containing protein, extracellular calcium-sensing receptor, and ubiquitin-protein ligase BRE1, which indicate modulation of intracellular signaling and stress perception.

- Amino acid and energy metabolism: aspartate kinase, proline-rich protein, and ATP-binding protein, reflecting adaptive shifts in nitrogen and energy metabolism.

- Lipid and membrane metabolism: delta-9 desaturase, desaturase, and plastidial delta-12 oleate desaturase, likely associated with maintaining membrane fluidity under dehydration.

- Antioxidant-related genes: two germins and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, implying reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification capacity during drought.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

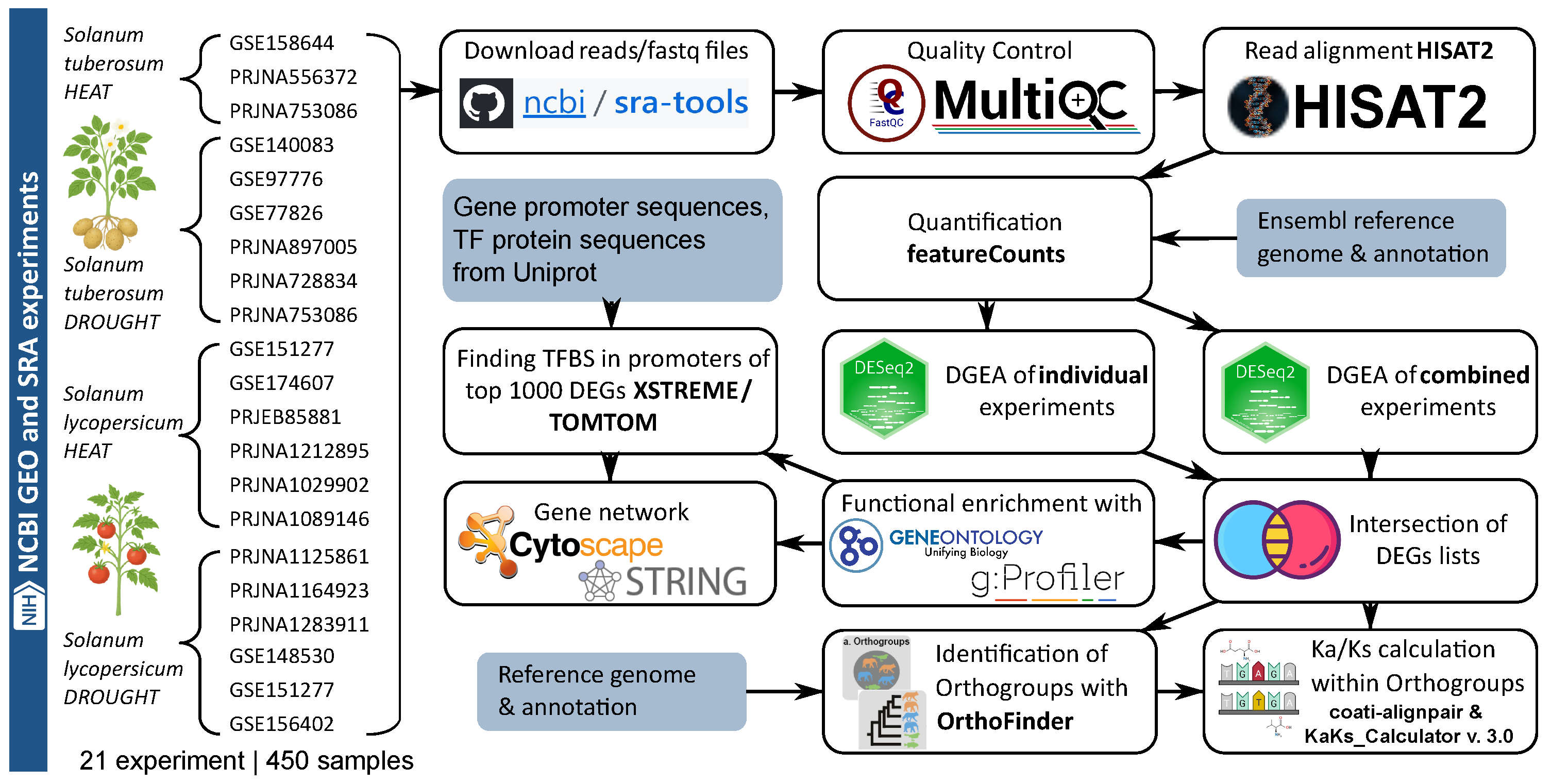

4.1. Pipeline for Identification and Systematic Analysis of Key Differentially Expressed Genes in Solanum tuberosum and Solanum lycopersicum Under Drought and Heat Stress

4.2. Search and Selection of Relevant Transcriptomic Experiments for Analysis

4.3. RNA-Seq Data Processing

4.4. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

4.5. Enrichment Analysis and Functional Annotation

4.6. Promoter Analysis and Motif Identification

4.7. Orthogroup Identification and Evolutionary Analysis

4.8. Gene Network Reconstruction, Analysis, and Visualization

- Motif-based regulatory associations. Statistically enriched promoter motifs specifically associated with subsets of up- and downregulated genes were identified using MEME/XSTREME (see Section 4.6). These motifs were used to infer potential transcriptional regulatory links.

- Coexpression relationships. Gene coexpression networks were reconstructed using the WGCNA package [104]. Adaptive correlation thresholds were applied depending on the number of experiments within each subset [47]:

- S. lycopersicum (drought): threshold 0.4, 6 experiments;

- S. lycopersicum (heat): threshold 0.4, 6 experiments;

- S. tuberosum (drought): threshold 0.4, 6 experiments;

- S. tuberosum (heat): threshold 0.9, 3 experiments.

WGCNA was performed with the following settings: an unsigned network (networkType = “unsigned”), soft-thresholding power chosen by the pickSoftThreshold function to attain scale-free topology, unsigned TOM (TOMType = “unsigned”), average linkage hierarchical clustering for gene dendrogram construction, dynamic module detection (cutreeDynamic) with deepSplit = 2 and a minimum module size of 30 genes, and module merging based on eigengene correlation > 0.75. - Protein–protein interactions (PPIs). Experimentally validated and database-curated interactions were retrieved from STRING (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 10 October 2025) [105]. Protein identifiers were imported using the proteins by sequences option, with the following parameters: evidence sources were set to experiments and databases, and the minimum interaction score was defined as medium confidence (0.400).

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| GRN | gene regulatory network |

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| LFC | fold change |

| TF | transcription factor |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HOGs | hierarchical orthologous groups |

| HSF | heat shock transcription factors |

References

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis; Agenda; The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 6, 333p. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Schafleitner, R.; Ramirez, J.; Jarvis, A.; Evers, D.; Gutierrez, R.; Scurrah, M. Adaptation of the potato crop to changing climates. In Crop Adaptation to Climate Change; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelton, E.; Fraser, E.D.; Termansen, M.; Benton, T.G.; Gosling, S.N.; South, A.; Arnell, N.W.; Challinor, A.J.; Dougill, A.J.; Forster, P.M. The socioeconomics of food crop production and climate change vulnerability: A global scale quantitative analysis of how grain crops are sensitive to drought. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkort, A.; Verhagen, A. Climate change and its repercussions for the potato supply chain. Potato Res. 2008, 51, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneveux, P.; Ramírez, D.A.; Pino, M.T. Drought tolerance in potato (S. tuberosum L.): Can we learn from drought tolerance research in cereals? Plant Sci. 2013, 205, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Veilleux, R.E. Adaptation of potato to high temperatures and salinity-a review. Am. J. Potato Res. 2007, 84, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Fogelman, E.; Belausov, E.; Ginzberg, I. Potato root system development and factors that determine its architecture. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 205, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, K.; Yamaguchi, J. Abiotic stresses. In Handbook of Potato Production, Improvement, and Postharvest Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; Chapter 7; pp. 231–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kear, P.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Luo, M.; Li, J. Effect of elevated temperature and CO2 on growth of two early-maturing potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) varieties. Clim. Smart Agric. 2025, 2, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Sang, W.G.; Baek, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, P.; Seo, M.C.; Cho, J.I. The effect of concurrent elevation in CO2 and temperature on the growth, photosynthesis, and yield of potato crops. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblonde, P.; Ledent, J.F. Effects of moderate drought conditions on green leaf number, stem height, leaf length and tuber yield of potato cultivars. Eur. J. Agron. 2001, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.N.; Govindakrishnan, P.; Swarooparani, D.; Nitin, C.; Surabhi, J.; Aggarwal, P. Assessment of impact of climate change on potato and potential adaptation gains in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2015, 9, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiasu, B.K.; Soundy, P.; Hammes, P.S. Response of potato (Solarium tuberosum) tuber yield components to gel-polymer soil amendments and irrigation regimes. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2007, 35, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafleitner, R.; Gutierrez, R.; Espino, R.; Gaudin, A.; Pérez, J.; Martínez, M.; Domínguez, A.; Tincopa, L.; Alvarado, C.; Numberto, G.; et al. Field screening for variation of drought tolerance in Solanum tuberosum L. by agronomical, physiological and genetic analysis. Potato Res. 2007, 50, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, L. Physiology of tuberization in plants. (Tubers and tuberous roots.). In Differenzierung und Entwicklung/Differentiation and Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1965; pp. 1328–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J. The effect of night temperature on tuber initiation of the potato. Eur. Potato J. 1968, 11, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Claussen, K.; Zimmerman, J.L. Genotypic differences in the heat-shock response and thermotolerance in four potato cultivars. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemette, A.M.; Hernández Casanova, G.; Hamilton, J.P.; Pokorná, E.; Dobrev, P.I.; Motyka, V.; Rashotte, A.M.; Leisner, C.P. The physiological and molecular responses of potato tuberization to projected future elevated temperatures. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiae664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rykaczewska, K. The impact of high temperature during growing season on potato cultivars with different response to environmental stresses. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 2386–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, J.; Rawat, S.; Govindakrishnan, P.; Kumar, D. Possibilities of enhancing potato production in non-traditional areas. Potato J. 2011, 38, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw, A.; Bonierbale, M.; Khan, M. Integrative breeding strategy for making climate-smart potato varieties for sub-Saharan Africa. In Potato and Sweetpotato in Africa: Transforming the Value Chains for Food and Nutrition Security; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2015; pp. 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xia, G.; Yang, H.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y. Deleterious effects of heat stress on the tomato, its innate responses, and potential preventive strategies in the realm of emerging technologies. Metabolites 2024, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wolters-Arts, M.; Mariani, C.; Huber, H.; Rieu, I. Heat stress affects vegetative and reproductive performance and trait correlations in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Euphytica 2017, 213, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, V.; Qadir, S.U.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Impact of drought and heat stress individually and in combination on physio-biochemical parameters, antioxidant responses, and gene expression in Solanum lycopersicum. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarok, S.; Jadid, N.; Widiastuti, A.; Derajat Matra, D.; Budiarto, R.; Lestari, F.W.; Nuraini, A.; Suminar, E.; Pradana Nur Rahmat, B.; Ezura, H. Parthenocarpic tomato mutants, iaa9-3 and iaa9-5, show plant adaptability and fruiting ability under heat-stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1090774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkostefanakis, S.; Mesihovic, A.; Simm, S.; Paupière, M.J.; Hu, Y.; Paul, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Tschiersch, B.; Theres, K.; Bovy, A.; et al. HsfA2 Controls the Activity of Developmentally and Stress-Regulated Heat Stress Protection Mechanisms in Tomato Male Reproductive Tissues. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 2461–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkostefanakis, S.; Simm, S.; El-Shershaby, A.; Hu, Y.; Bublak, D.; Mesihovic, A.; Darm, K.; Mishra, S.K.; Tschiersch, B.; Theres, K.; et al. The repressor and co-activator HsfB1 regulates the major heat stress transcription factors in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y. Genome-wide identification of C2H2 zinc-finger genes and their expression patterns under heat stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). PeerJ 2019, 7, e7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yu, X.; Ottosen, C.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, T. Unique miRNAs and their targets in tomato leaf responding to combined drought and heat stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayafi, A.A.M. Exogenous ascorbic acid induces systemic heat stress tolerance in tomato seedlings: Transcriptional regulation mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 27, 19186–19199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhtar, T.; Rehman, S.U.; Smith, D.L.; Sultan, T.; Seleiman, M.F.; Alsadon, A.A.; Amna; Ali, S.; Chaudhary, H.J.; Solieman, T.; et al. Mitigation of Heat Stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by ACC-deaminase and Exopolysaccharide Producing Bacillus cereus: Effects on Biochemical Profiling. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, M.; Meneses, C.; Riquelme, S.; Pinto, M.; Lagüe, M.; Davidson, C.; Tai, H.H. Transcriptome profiles of contrasting potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes under water stress. Agronomy 2019, 9, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczynski, M.; Wyrzykowska, A.; Milanowska, K.; Boguszewska-Mankowska, D.; Zagdanska, B.; Karlowski, W.; Jarmolowski, A.; Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z. Genomewide identification of genes involved in the potato response to drought indicates functional evolutionary conservation with Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, H.; Kurowsky, C.; Horn, R.; Erban, A.; Seddig, S.; Rudack, K.; Fischer, A.; Walther, D.; Zuther, E.; Köhl, K.; et al. The drought response of potato reference cultivars with contrasting tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2370–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Morezuelas, A.; Barandalla, L.; Ritter, E.; Ruiz de Galarreta, J.I. Transcriptome analysis of two tetraploid potato varieties under water-stress conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, R.; Zhang, W.; Shang, L.; Wang, J.; Khassanov, V.; Lyu, D. Construction of drought stress regulation networks in potato based on SMRT and RNA sequencing data. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Joshi, J.; Borza, T.; Aqa, M.M.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, H.; Wang-Pruski, G. Exogenous phosphite application alleviates the adverse effects of heat stress and improves thermotolerance of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) seedlings. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Park, S.J.; Kwon, S.Y.; Shin, A.Y.; Moon, K.B.; Park, J.M.; Cho, H.S.; Park, S.U.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Temporally distinct regulatory pathways coordinate thermo-responsive storage organ formation in potato. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragkostefanakis, S.; Simm, S.; Paul, P.; Bublak, D.; SCHARF, K.D.; Schleiff, E. Chaperone network composition in S olanum lycopersicum explored by transcriptome profiling and microarray meta-analysis. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhan, X. Elucidating the role of SlBBX31 in plant growth and heat-stress resistance in tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wu, T.; Pei, T.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Xu, X. Overexpression of SlGATA17 promotes drought tolerance in transgenic tomato plants by enhancing activation of the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 634888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Wu, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Pei, T.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Xu, X. Genome-wide analyses of the genetic screening of C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factors and abiotic and biotic stress responses in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) based on RNA-Seq data. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todaka, D.; Quynh, D.T.N.; Tanaka, M.; Utsumi, Y.; Utsumi, C.; Ezoe, A.; Takahashi, S.; Ishida, J.; Kusano, M.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Application of ethanol alleviates heat damage to leaf growth and yield in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1325365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benny, J.; Pisciotta, A.; Caruso, T.; Martinelli, F. Identification of key genes and its chromosome regions linked to drought responses in leaves across different crops through meta-analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrovskikh, A.V.; Zubairova, U.S.; Bondar, E.I.; Lavrekha, V.V.; Doroshkov, A.V. Transcriptomic data meta-analysis sheds light on high light response in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrovskikh, A.V.; Zubairova, U.S.; Doroshkov, A.V. Identification of Key Differentially Expressed Genes in Arabidopsis thaliana Under Short-and Long-Term High Light Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admas, T.; Jiao, S.; Pan, R.; Zhang, W. Pan-omics insights into abiotic stress responses: Bridging functional genomics and precision crop breeding. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2025, 25, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Fatima, K.; Sadaqat, M.; Tahir ul Qamar, M. Disease Resistance at the Molecular Level: Omics-Based Approaches for Tomato Defense. In Omics Approaches for Tomato Yield and Quality Trait Improvement; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascher, M.; Jayakodi, M.; Shim, H.; Stein, N. Promises and challenges of crop translational genomics. Nature 2024, 636, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, M.; Jayakodi, M.; Stein, N.; Mascher, M. Plant pangenomes for crop improvement, biodiversity and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, M.; Jenike, K.M.; Satterlee, J.W.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Gentile, I.; Hendelman, A.; Passalacqua, M.J.; Suresh, H.; Shohat, H.; Robitaille, G.M.; et al. Solanum pan-genetics reveals paralogues as contingencies in crop engineering. Nature 2025, 640, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Yang, D.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, C.; Yan, Y.; Lamin-Samu, A.T.; Wang, Q.; Xu, X.; Fei, Z.; Lu, G. Tomato stigma exsertion induced by high temperature is associated with the jasmonate signalling pathway. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1205–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Gao, Y.; Cai, J.; Li, D.; Song, F. Tomato stress-associated protein 4 contributes positively to immunity against necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2019, 32, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Katano, K. Coordination between ROS regulatory systems and other pathways under heat stress and pathogen attack. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, A.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Chang, R.; Liu, D.; Ahammed, G.J.; Lin, X. Overexpression of mitochondrial uncoupling protein conferred resistance to heat stress and Botrytis cinerea infection in tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 73, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kang, H. Recent insights into the physio-biochemical and molecular mechanisms of low temperature stress in tomato. Plants 2024, 13, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, P.; Bao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhu, X.; et al. Genome evolution and diversity of wild and cultivated potatoes. Nature 2022, 606, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Hedges, S.B. TimeTree: A resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 1812–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, S.; Gul, H.; Shahzad, M.; Ullah, I.; Shahzad, A.; Khan, S.U. Comprehensive analysis of potato (Solanum tuberosum) PYL genes highlights their role in stress responses. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, FP24094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamoud, Y.A.; Noman, M.; Yang, X.; Ahmed, T.; Alwutayd, K.M.; Qin, H.; Shaghaleh, H. Integrated multi-omics and transcriptomic analysis reveals key regulatory networks of heat stress responses in potato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 228, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Duan, X.; Majeed, Y.; Luo, J.; Guan, N.; Zheng, H.; Zou, H.; Jin, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Functional analysis of StWRKY75 gene in response to heat stress in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1617625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Muijen, D.; Anithakumari, A.; Maliepaard, C.; Visser, R.G.; van der Linden, C.G. Systems genetics reveals key genetic elements of drought induced gene regulation in diploid potato. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1895–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Ali, K.; Wang, Y.; Dormatey, R.; Yao, P.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Bai, J. Global transcriptome and coexpression network analyses reveal cultivar-specific molecular signatures associated with different rooting depth responses to drought stress in potato. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1007866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Jian, H.; Shang, L.; Kear, P.J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Yuan, P.; Lyu, D. Comprehensive transcriptional regulatory networks in potato through chromatin accessibility and transcriptome under drought and salt stresses. Plant J. 2025, 121, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyan, S.; Rao, S.; Jha, S.; Bansal, C.; Das, J.R.; Mathur, S. Characterization of novel regulators for heat stress tolerance in tomato from Indian sub-continent. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2118–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoi, J.; Todaka, D.; Imatomi, T.; Kidokoro, S.; Sakurai, T.; Kodaira, K.S.; Takayama, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. The ability to induce heat shock transcription factor-regulated genes in response to lethal heat stress is associated with thermotolerance in tomato cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1269964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S.; Barone, A. Tomato plant response to heat stress: A focus on candidate genes for yield-related traits. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1245661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Transcriptome analysis and metabolic profiling reveal the key regulatory pathways in drought stress responses and recovery in tomatoes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Qing, Q.; Deng, C.; Wang, H.; Song, Y. Screening and Identification of Drought-Tolerant Genes in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Based on RNA-Seq Analysis. Plants 2025, 14, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurek, M.; Smolibowski, M. Variability of plant transcriptomic responses under stress acclimation: A review from high throughput studies. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2024, 71, 13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Riquelme, J.S.; Contreras, M.; Moyano, T.C.; Sjoberg, R.; Jimenez-Gomez, J.; Alvarez, J.M. Desert-adapted tomato Solanum pennellii exhibit unique regulatory elements and stress-ready transcriptome patterns to drought. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, S.; Su, W.; Guo, H.; Ye, G.; Wang, J. Metabolome and transcriptome analyses reveal molecular responses of two potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivars to cold stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1543380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Nie, X.; Kong, W.; Deng, X.; Sun, T.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Genome-wide identification and evolution analysis of the gibberellin oxidase gene family in six gramineae crops. Genes 2022, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhai, J.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Martine, C.; Ma, H.; et al. Nuclear phylogeny and insights into whole-genome duplications and reproductive development of Solanaceae plants. Plant Commun. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidou, M.; Anglin, N.L.; Ellis, D.; Tai, H.H.; Strömvik, M.V. Genome assembly of six polyploid potato genomes. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achakkagari, S.; Bozan, I.; Camargo-Tavares, J.; McCoy, H.; Portal, L.; Soto, J.; Bizimungu, B.; Anglin, N.; Manrique-Carpintero, N.; Lindqvist-Kreuze, H.; et al. The phased Solanum okadae genome and Petota pangenome analysis of 23 other potato wild relatives and hybrids. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, M.; Zhang, N.; Si, H. Transcriptome analysis of potato leaves under oxidative stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrovskikh, A.; Zubairova, U.; Kolodkin, A.; Doroshkov, A. Subcellular compartmentalization of the plant antioxidant system: An integrated overview. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, P.; Sui, C.; Niu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, F.; Yan, J.; Guo, S. Comparative transcriptomic analysis and functional characterization reveals that the class III peroxidase gene TaPRX-2A regulates drought stress tolerance in transgenic wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1119162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Hernández, M.; Arbona, V.; Simon, I.; Rivero, R.M. Specific ABA-independent tomato transcriptome reprogramming under abiotic stress combination. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1746–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, R.K.; Trowbridge, A.M.; Lindroth, R.L.; Lerdau, M.T. Coordinated resource allocation to plant growth–defense tradeoffs. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Sharifova, S.; Zhao, X.; Sinha, N.; Nakayama, H.; Tellier, A.; Silva-Arias, G.A. Evolution of gene networks underlying adaptation to drought stress in the wild tomato Solanum chilense. Mol. Ecol. 2024, 33, e17536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Kong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y. Gene and metabolite integration analysis through transcriptome and metabolome brings new insight into heat stress tolerance in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plants 2021, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliche, E.B.; Gengler, T.; Hoendervangers, I.; Oortwijn, M.; Bachem, C.W.; Borm, T.; Visser, R.G.; van der Linden, C.G. Transcriptomic responses of potato to drought stress. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.Z.; Ma, S.Y.; Ma, X.H.; Song, Y.; Wang, X.M.; Cheng, G.X. Transcriptome analyses show changes in heat-stress related gene expression in tomato cultivar ‘Moneymaker’under high temperature. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, G.; Huang, X.; Pan, T.; Chen, W.; Qu, M.; Ouyang, B.; Yu, M.; Shabala, S. Candidate regulators of drought stress in tomato revealed by comparative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1282718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhu, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Genome-wide identification and characterization of cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase genes in tomato and their expression profile in response to heat stress. Diversity 2021, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Psaroudakis, D.; Rolletschek, H.; Neumann, K.; Borisjuk, L.; Himmelbach, A.; Pinninti, K.; Töpfer, N.; Szymanski, J. panomiX: Investigating Mechanisms Of Trait Emergence Through Multi-Omics Data Integration. Plant Phenomics 2025, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, R.R.; Vraggalas, S.; Keller, M.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; McNicoll, F.; Löchli, K.; Bublak, D.; Benhamed, M.; Crespi, M.; Berberich, T.; et al. A plant-specific clade of serine/arginine-rich proteins regulates RNA splicing homeostasis and thermotolerance in tomato. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 11466–11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, A.J.; Bhatt, J.J.; Brewer, H.M.; Kintigh, J.; Kariuki, S.M.; Rudrabhatla, S.; Adkins, J.N.; Curtis, W.R. Phloem exudate protein profiles during drought and recovery reveal abiotic stress responses in tomato vasculature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolami, G.; de Werk, T.A.; Larter, M.; Thonglim, A.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Balazadeh, S.; Lens, F. Integrating gene expression analysis and ecophysiological responses to water deficit in leaves of tomato plants. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.Q.; Rejab, N.A.; Taheri, S.; Teo, C.H. Elucidating the roles of small open reading frames towards drought stress in Solanum lycopersicum. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2025, 25, e510625112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, G.; Pertea, M. GFF utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Research 2020, 9, ISCB Comm J-304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. KaKs_Calculator 3.0: Calculating selective pressure on coding and non-coding sequences. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Nastou, K.; Koutrouli, M.; Kirsch, R.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Hu, D.; Peluso, M.E.; Huang, Q.; Fang, T.; et al. The STRING database in 2025: Protein networks with directionality of regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D730–D737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, D.; Haider, S.; Ballester, B.; Holland, R.; London, D.; Thorisson, G.; Kasprzyk, A. BioMart–biological queries made easy. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GEO/Project ID | Number of Samples 1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Solanum tuberosum | ||

| heat stress: | ||

| GSE158644 | 12 | [39] |

| PRJNA556372 | 18 | [38] |

| PRJNA753086 | 18 | — |

| drought stress: | ||

| GSE140083 | 24 | [33] |

| GSE97776 | 54 | [34] |

| GSE77826 | 48 | [35] |

| PRJNA897005 | 20 | [36] |

| PRJNA728834 | 21 | [37] |

| PRJNA753086 | 17 | — |

| Solanum lycopersicum | ||

| heat stress: | ||

| GSE151277 | 15 | [41] |

| GSE174607 | 12 | [91] |

| PRJEB85881 | 98 | [92] |

| PRJNA1212895 | 6 | — |

| PRJNA1029902 | 6 | — |

| PRJNA1089146 | 6 | [93] |

| drought stress: | ||

| GSE148530 | 8 | [42,43] |

| GSE151277 | 18 | [41] |

| GSE156402 | 12 | [94] |

| PRJNA1125861 | 27 | [95] |

| PRJNA1164923 | 4 | [96] |

| PRJNA1283911 | 6 | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bondar, E.I.; Zubairova, U.S.; Bobrovskikh, A.V.; Doroshkov, A.V. Integrative Transcriptomic and Evolutionary Analysis of Drought and Heat Stress Responses in Solanum tuberosum and Solanum lycopersicum. Plants 2025, 14, 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243851

Bondar EI, Zubairova US, Bobrovskikh AV, Doroshkov AV. Integrative Transcriptomic and Evolutionary Analysis of Drought and Heat Stress Responses in Solanum tuberosum and Solanum lycopersicum. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243851

Chicago/Turabian StyleBondar, Eugeniya I., Ulyana S. Zubairova, Aleksandr V. Bobrovskikh, and Alexey V. Doroshkov. 2025. "Integrative Transcriptomic and Evolutionary Analysis of Drought and Heat Stress Responses in Solanum tuberosum and Solanum lycopersicum" Plants 14, no. 24: 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243851

APA StyleBondar, E. I., Zubairova, U. S., Bobrovskikh, A. V., & Doroshkov, A. V. (2025). Integrative Transcriptomic and Evolutionary Analysis of Drought and Heat Stress Responses in Solanum tuberosum and Solanum lycopersicum. Plants, 14(24), 3851. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243851