Identification of the Populus euphratica XTHs Gene Family and the Response of PeXTH7 to Abiotic Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Prediction of Physical and Chemical Properties of PeXTHs Family Members

2.2. Analysis of Gene and Protein Structure of PeXTHs

2.3. Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements in PeXTHs Promoter Region

2.4. Collinearity Analysis of XTHs Within P. euphratica and Among Multiple Species

2.5. Chromosomal Localization Analysis of PeXTHs

2.6. Phylogenetic Tree of PeXTHs

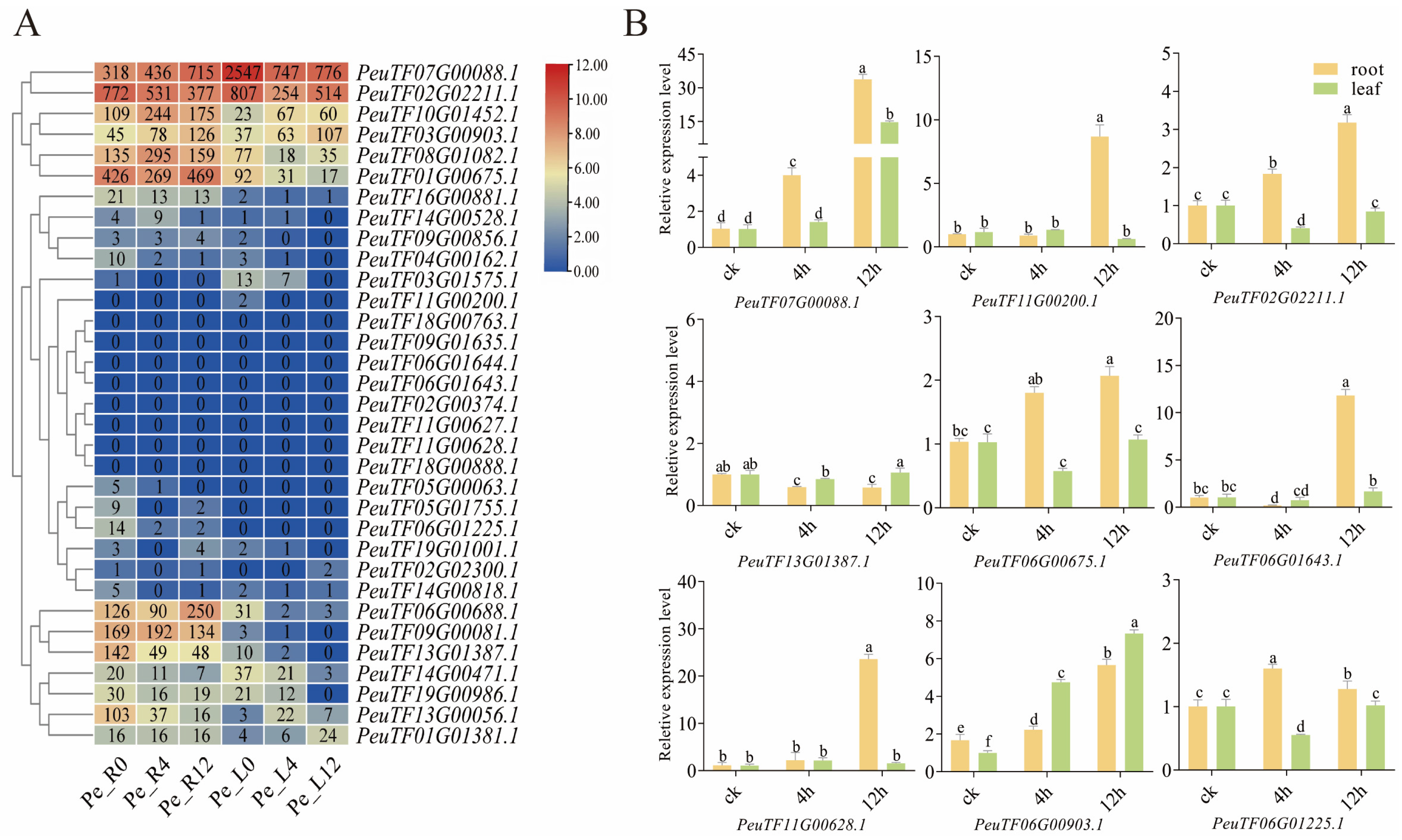

2.7. PeXTH Transcriptome Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.8. Subcellular Localization of PeXTH7 in Nicotiana benthamiana

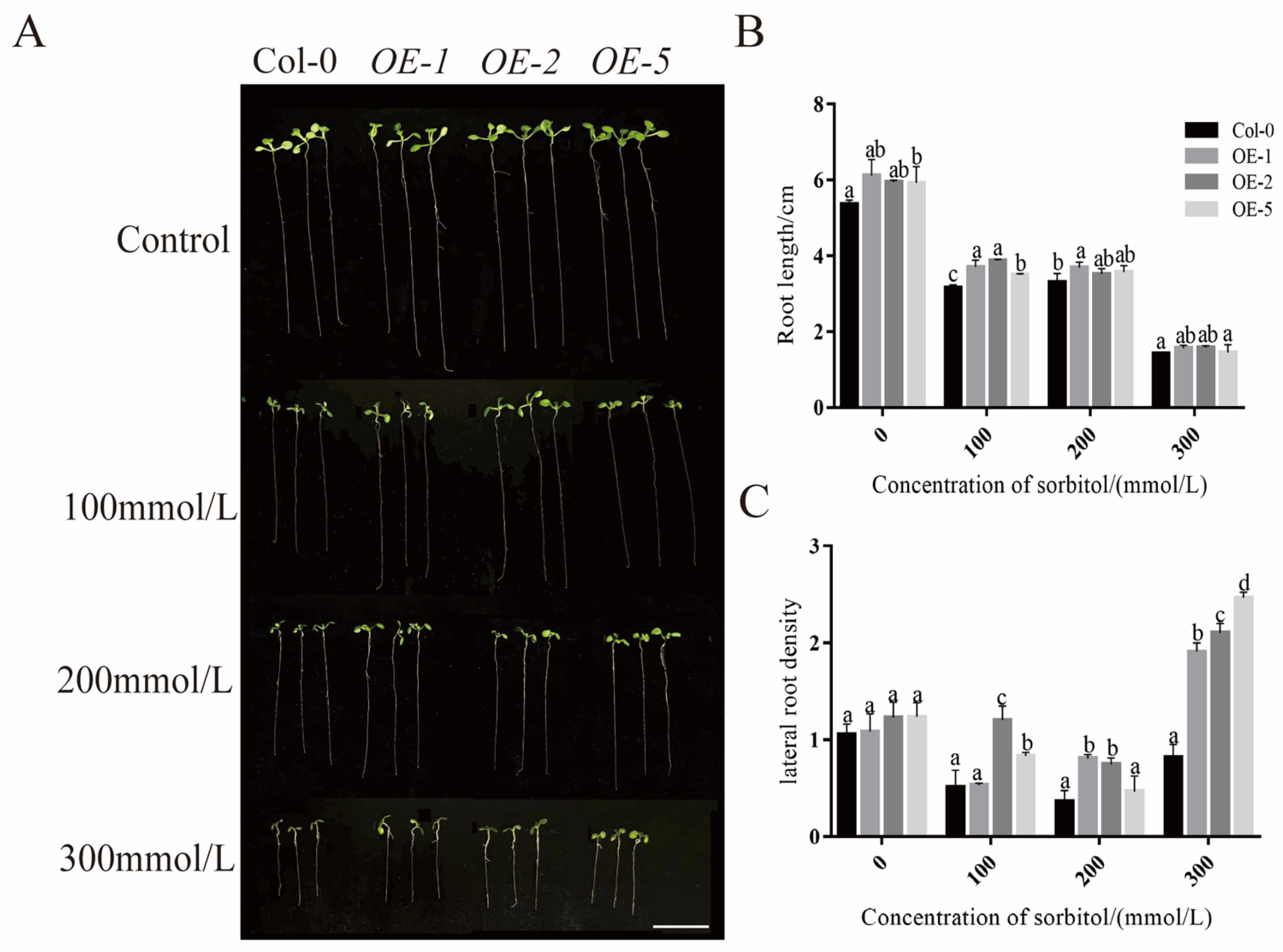

2.9. Effect of PeXTH7 Overexpression on the Regulation of Root System Development in Transgenic A. thaliana

3. Discussion

3.1. Identification of 33 XTH Family Members in P. euphratica

3.2. Potential Biological Functions of the PeXTH Gene Family

3.3. PeXTH7 Participates in the Regulation of Root Length in Transgenic A. thaliana

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genetic Identification, Physical and Chemical Property Analysis

4.2. PeXTH Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis

4.3. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements of PeXTH Promoter

4.4. Collinearity and Chromosome Mapping Among Multiple Species

4.5. PeXTH Phylogenetic Tree Analysis

4.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Data Analysis of PeXTHs

4.7. Subcellular Localization of PeXTH7

4.8. Effect of PeXTH7 Overexpression on Root Length in A. thaliana

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, Y.; Xiong, L. General mechanisms of drought response and their application in drought resistance improvement in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 673–689. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad Aslam, M.; Waseem, M. Mechanisms of Abscisic Acid-Mediated Drought Stress Responses in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1084–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Teeples, M.; Lin, L.; de Lucas, M.; Turco, G.; Toal, T.W.; Gaudinier, A.; Young, N.F.; Trabucco, G.M.; Veling, M.T.; Lamothe, R. An Arabidopsis gene regulatory network for secondary cell wall synthesis. Nature 2015, 517, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zayed, O.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, P.; Hsu, C.C.; Zhang, L.; Tao, W.A.; Lozano-Durán, R.; Zhu, J.K. Leucine-rich repeat extensin proteins regulate plant salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 13123–13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, P.; Urbancsok, J.; Donev, E.N.; Derba-Maceluch, M.; Barbut, F.R. Modification of xylan in secondary walls alters cell wall biosynthesis and wood formation programs and improves saccharification. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Lindner, H. Growing Out of Stress: The Role of Cell- and Organ-Scale Growth Control in Plant Water-Stress Responses. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 28, 1769–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Caroli, M.; Manno, E.; Piro, G. Ride to cell wall: Arabidopsis XTH11, XTH29 and XTH33 exhibit different secretion pathways and responses to heat and drought stress. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, K.; Tominaga, R. Endo-xyloglucan transferase, a novel class of glycosyltransferase that catalyzes transfer of a segment of xyloglucan molecule to another xyloglucan molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 21058–21064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Li, Z.; Si, J.; Zhang, S.; Han, X.; Chen, X. Structural and Functional Responses of the Heteromorphic Leaves of Different Tree Heights on Populus euphratica Oliv. to Different Soil Moisture Conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 2376–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.L.; Zhang, L.; Du, J.J.; Wen, S.S.; Qu, G.Z.; Hu, J.J. Transcriptome Analysis of Populus euphratica under Salt Treatment and PeERF1 Gene Enhances Salt Tolerance in Transgenic Populus alba × Populus glandulosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3727–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, R.A.; Koevoets, I.T.; Testerink, C. Out of Shape During Stress: A Key Role for Auxin. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Li, J.; Huang, Z.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M.; Hao, P.; Zhou, W.; Li, J. Reproductive characteristics of a Populus euphratica population and prospects for its restoration in China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 39121–39128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, D.; Kang, M.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Improved genome assembly provides new insights into genome evolution in a desert poplar (Populus euphratica). Plant Physiol. 2020, 20, 781–794. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sheen, J. ABA-activated low-nanomolar Ca2+-CPK signalling controls root cap cycle plasticity and stress adaptation. Nat. Plants 2024, 11, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Nishitani, K. A comprehensive expression analysis of all members of a gene family encoding cell-wall enzymes allowed us to predict cis-regulatory regions involved in cell-wall construction in specific organs of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, R.; Rose, J.K.; Nishitani, K. A Surprising Diversity and Abundance of Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolases in Rice. Classification and Expression Analysis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Han, Q. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase genes family in Salicaceae during grafting. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Gao, H.; Guo, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, A. The alpha- and beta-expansin and xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene families of wheat: Molecular cloning, gene expression, and EST data mining. Genomics 2007, 90, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultink, A.; Liu, L.; Zhu, L.; Pauly, M. Structural Diversity and Function of Xyloglucan Sidechain Substituents. Plants 2014, 3, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Zhong, S.; Fang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Dong, B.; Zhao, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of XTH Gene Family during Flower-Opening Stages in Osmanthus fragrans. Plants 2022, 11, 1015–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Yin, C.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Ge, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylase/Hydrolase in Ananas comosus during Development. Genes 2019, 10, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Z. The XTH Gene Family in Schima superba: Genome-Wide Identification, Expression Profiles, and Functional Interaction Network Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 911761–911776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladié, M.; Rose, J.K.; Cosgrove, D.J.; Catalá, C. Characterization of a new xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) from ripening tomato fruit and implications for the diverse modes of enzymic action. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006, 47, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Seo, Y.S.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, W.T.; Shin, J.S. Constitutive expression of CaXTH3, a hot pepper xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase, enhanced tolerance to salt and drought stresses without phenotypic defects in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Dotaerang). Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wan, H.; Zhao, H.; Dai, X.; Wu, W.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, R.; Xu, B.; Zeng, C.; et al. Identification and expression analysis of the Xyloglucan transglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) gene family under abiotic stress in oilseed (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Z. Chromosome-scale assemblies of the male and female Populus euphratica genomes reveal the molecular basis of sex determination and sexual dimorphism. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xu, J.; Qiu, C.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z. The chromosome-scale genome and population genomics reveal the adaptative evolution of Populus pruinosa to desertification environment. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jiang, Z. Multi-omics analysis reveals spatiotemporal regulation and function of heteromorphic leaves in Populus. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y. The plant cell wall: Biosynthesis, construction, and functions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Structure and growth of plant cell walls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 25, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoson, T. Apoplast as the site of response to environmental signals. J. Plant Res. 1998, 111, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbut, F.R. Plant-Insect Interactions. Plants 2022, 11, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.H. Secondary cell walls: Biosynthesis, patterned deposition and transcriptional regulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamet, E.; Canut, H.; Boudart, G.; Pont-Lezica, R.F. Cell wall proteins: A new insight through proteomics. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderan-Rodrigues, M.J.; Guimarães Fonseca, J.; de Moraes, F.E.; Vaz Setem, L.; Carmanhanis Begossi, A.; Labate, C.A. Plant Cell Wall Proteomics: A Focus on Monocot Species, Brachypodium distachyon, Saccharum spp. and Oryza sativa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1975–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franková, L.; Fry, S.C. Biochemistry and physiological roles of enzymes that ‘cut and paste’ plant cell-wall polysaccharides. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3519–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, M.; Roujol, D.; Nguyen-Kim, H.; Del Rocio Cisneros Castillo, L.; Saland, E.; Jamet, E.; Albenne, C. Arabinogalactan protein 31 (AGP31), a putative network-forming protein in Arabidopsis thaliana cell walls. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Eberhard, S.; Pattathil, S.; Warder, C.; Glushka, J.; Yuan, C.; Hao, Z.; Zhu, X.; Avci, U.; Miller, J.S.; et al. An Arabidopsis cell wall proteoglycan consists of pectin and arabinoxylan covalently linked to an arabinogalactan protein. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.C.; Terneus, K.; Hall, Q.; Tan, L.; Wang, Y.; Wegenhart, B.L.; Chen, L.; Lamport, D.T.; Chen, Y.; Kieliszewski, M.J. Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extensin scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2226–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, N.; Nishitani, K. Cryogenian Origin and Subsequent Diversification of the Plant Cell-Wall Enzyme XTH Family. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1874–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Qi, D.; Fang, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Genome-wide characterization of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase family genes and their response to plant hormone in sugar beet. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108239–108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, R.; Keuskamp, D.H.; Kooke, R.; Voesenek, L.A.; Pierik, R. Interactions between auxin, microtubules and XTHs mediate green shade- induced petiole elongation in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Han, S.; Ban, Q.; He, Y.; Jin, M.; Rao, J. Overexpression of persimmon DkXTH1 enhanced tolerance to abiotic stress and delayed fruit softening in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, A.; Dou, W.; Qi, J.; Long, Q.; Zou, X.; Lei, T.; Yao, L.; He, Y.; Chen, S. Systematic Analysis and Functional Validation of Citrus XTH Genes Reveal the Role of Csxth04 in Citrus Bacterial Canker Resistance and Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Pang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Sun, Q. Identification and expression analysis of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). PeerJ 2022, 10, e13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisler-Lee, J.; Geisler, M.; Coutinho, P.M.; Segerman, B.; Nishikubo, N.; Takahashi, J.; Aspeborg, H.; Djerbi, S.; Master, E.; Andersson-Gunnerås, S.; et al. Poplar carbohydrate-active enzymes. Gene identification and expression analyses. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 946–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.E.; Fry, S.C. Restructuring of wall-bound xyloglucan by transglycosylation in living plant cells. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2001, 26, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauret-Güeto, S.; Calder, G.; Harberd, N.P. Transient gibberellin application promotes Arabidopsis thaliana hypocotyl cell elongation without maintaining transverse orientation of microtubules on the outer tangential wall of epidermal cells. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 69, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovesi, V.; Fornalé, S.; Fry, S.C.; Ruel, K.; Ferrer, P.; Encina, A.; Sonbol, F.M.; Bosch, J.; Puigdomènech, P.; Rigau, J.; et al. ZmXTH1, a new xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase in maize, affects cell wall structure and composition in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.B.; Lu, S.M.; Zhang, J.F.; Liu, S.; Lu, Y.T. A xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase involves in growth of primary root and alters the deposition of cellulose in Arabidopsis. Planta 2007, 226, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Tripathi, S.K.; Nath, P.; Sane, A.P. Petal abscission in rose is associated with the differential expression of two ethylene-responsive xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase genes, RbXTH1 and RbXTH2. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5091–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittkopp, P.J.; Kalay, G. Cis-regulatory elements: Molecular mechanisms and evolutionary processes underlying divergence. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 13, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thessen, A.E.; Cooper, L.; Swetnam, T.L.; Hegde, H.; Reese, J.; Elser, J.; Jaiswal, P. Using knowledge graphs to infer gene expression in plants. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1201002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Feng, C. Genome-Wide Identification of the Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase (XTH) and Polygalacturonase (PG) Genes and Characterization of Their Role in Fruit Softening of Sweet Cherry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12331–12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, Q.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Kang, H.; Sha, L.; Fan, X.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Genome-wide identification of bHLH transcription factors and expression analysis under drought stress in Pseudoroegneria libanotica at germination. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants Int. J. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 30, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Nishitani, K. Endoxyloglucan transferase is localized both in the cell plate and in the secretory pathway destined for the apoplast in tobacco cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Ding, M.; Zhao, R.; Deng, S.; Wang, F.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Populus euphratica XTH overexpression enhances salinity tolerance by the development of leaf succulence in transgenic tobacco plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4225–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Xu, Y.; Yan, K.; Zhang, S.; Yang, G.; Wu, C.; Zheng, C. BREVIPEDICELLUS Positively Regulates Salt-Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhou, R.; Macaya-Sanz, D.; Carlson, C.H.; Schmutz, J. A willow sex chromosome reveals convergent evolution of complex palindromic repeats. Nat. Plants 2020, 21, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, P.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Qin, R.; Li, Z. Short-term transcriptomic responses of Populus euphratica roots and leaves to drought stress. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Bi, C.; He, B.; Ye, N.; Yin, T.; Xu, L.A. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the MADS-box gene family in Salix suchowensis. PeerJ 2019, 7, e8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene ID | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Number of Amino Acid (aa) | Aliphatic Index | Theoretical pI | Grand Average of Hydropathicity | Predicted Location (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PeuTF09G00081.1 | 33.05 | 294 | 68.03 | 6.15 | −0.486 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF18G00763.1 | 33.19 | 291 | 62.71 | 8.79 | −0.411 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF07G00088.1 | 24.7 | 213 | 60.05 | 5.95 | −0.546 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF09G01635.1 | 32.28 | 289 | 62.77 | 5.03 | −0.362 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF06G01644.1 | 32.66 | 287 | 69.62 | 6.59 | −0.307 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF06G01643.1 | 32.76 | 287 | 68.95 | 7.04 | −0.356 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF09G00856.1 | 34.1 | 294 | 65.31 | 8.9 | −0.494 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF08G01082.1 | 38 | 336 | 71.37 | 5.88 | −0.346 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF01G00675.1 | 33.55 | 289 | 59.38 | 6.22 | −0.512 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF13G00056.1 | 23.83 | 210 | 55.81 | 5.71 | −0.561 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF11G00200.1 | 34.94 | 299 | 56.45 | 5.09 | −0.585 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF04G00162.1 | 34.1 | 293 | 56.62 | 4.76 | −0.561 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF02G00374.1 | 25.69 | 224 | 83.57 | 8.51 | −0.242 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF05G01755.1 | 33.24 | 295 | 70.75 | 8.84 | −0.322 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF10G01452.1 | 38.21 | 335 | 71.28 | 6.07 | −0.417 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF01G01381.1 | 39.49 | 338 | 57.43 | 9.1 | −0.559 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF11G00627.1 | 33.37 | 292 | 71.44 | 8.99 | −0.399 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF11G00628.1 | 31.54 | 274 | 75.44 | 9.67 | −0.419 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF03G01575.1 | 35 | 300 | 65.33 | 8.4 | −0.387 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF14G00471.1 | 32.25 | 282 | 66.77 | 9.07 | −0.33 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF14G00528.1 | 30.82 | 264 | 67.95 | 8.87 | −0.539 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF03G00903.1 | 36.3 | 311 | 62.77 | 9 | −0.603 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF06G01225.1 | 33.88 | 294 | 60.75 | 9.58 | −0.443 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF02G02211.1 | 33.03 | 288 | 66.04 | 9.24 | −0.34 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF02G02300.1 | 33.55 | 293 | 58.6 | 5.64 | −0.606 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF06G00688.1 | 31.88 | 285 | 62.67 | 7.58 | −0.322 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF14G00818.1 | 34.88 | 311 | 70.84 | 6.49 | −0.251 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF19G00986.1 | 33.78 | 296 | 69.8 | 5.89 | −0.295 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF13G01387.1 | 28.12 | 246 | 58.66 | 5.8 | −0.498 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF16G00881.1 | 34.03 | 294 | 61.7 | 9.39 | −0.426 | Cell wall |

| PeuTF18G00888.1 | 33.23 | 292 | 71.16 | 8.95 | −0.383 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF05G00063.1 | 33.01 | 291 | 71.41 | 4.48 | −0.261 | Cell wall, Cytoplasm |

| PeuTF19G01001.1 | 33.78 | 296 | 69.8 | 5.89 | −0.295 | Cell wall |

| Gene_1 | Gene_2 | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PeuTF01G01381.1 | PeuTF03G00903.1 | 0.088029963 | 0.336819885 | 0.261356192 |

| PeuTF01G00675.1 | PeuTF03G01575.1 | 0.136741168 | 0.46409146 | 0.294642715 |

| PeuTF08G01082.1 | PeuTF10G01452.1 | 0.052476004 | 0.350912053 | 0.149541755 |

| PeuTF06G01643.1 | PeuTF18G00888.1 | 0.240293693 | 2.165085817 | 0.110985759 |

| PeuTF06G01225.1 | PeuTF09G00081.1 | 0.197261823 | 1.201835773 | 0.164133759 |

| PeuTF06G01225.1 | PeuTF16G00881.1 | 0.038836235 | 0.416044352 | 0.093346383 |

| PeuTF19G01001.1 | PeuTF13G01387.1 | 0.060220985 | 0.446202234 | 0.134963432 |

| PeuTF14G00528.1 | PeuTF02G02300.1 | 0.427698912 | NaN | NaN |

| PeuTF05G01755.1 | PeuTF11G00627.1 | 0.211307847 | NaN | NaN |

| PeuTF05G01755.1 | PeuTF02G00374.1 | 0.109048588 | 0.500680619 | 0.217800697 |

| PeuTF05G00063.1 | PeuTF13G00056.1 | 0.126769113 | 0.411406195 | 0.30813613 |

| PeuTF02G00374.1 | PeuTF11G00627.1 | 0.233638517 | NaN | NaN |

| PeuTF04G00162.1 | PeuTF11G00200.1 | 0.038976214 | 0.365085239 | 0.106759218 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Jin, H.; Song, T.; Miao, D.; Ning, Q.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Jiao, P.; Wu, Z. Identification of the Populus euphratica XTHs Gene Family and the Response of PeXTH7 to Abiotic Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243847

Li J, Jin H, Song T, Miao D, Ning Q, Sun J, Li Z, Jiao P, Wu Z. Identification of the Populus euphratica XTHs Gene Family and the Response of PeXTH7 to Abiotic Stress. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243847

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jing, Hongyan Jin, Tongrui Song, Donghui Miao, Qi Ning, Jianhao Sun, Zhijun Li, Peipei Jiao, and Zhihua Wu. 2025. "Identification of the Populus euphratica XTHs Gene Family and the Response of PeXTH7 to Abiotic Stress" Plants 14, no. 24: 3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243847

APA StyleLi, J., Jin, H., Song, T., Miao, D., Ning, Q., Sun, J., Li, Z., Jiao, P., & Wu, Z. (2025). Identification of the Populus euphratica XTHs Gene Family and the Response of PeXTH7 to Abiotic Stress. Plants, 14(24), 3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243847