Nitrogen Fertilisation Modulates Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidant Defence Mechanisms in Intercropped Cactus Under Semi-Arid Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

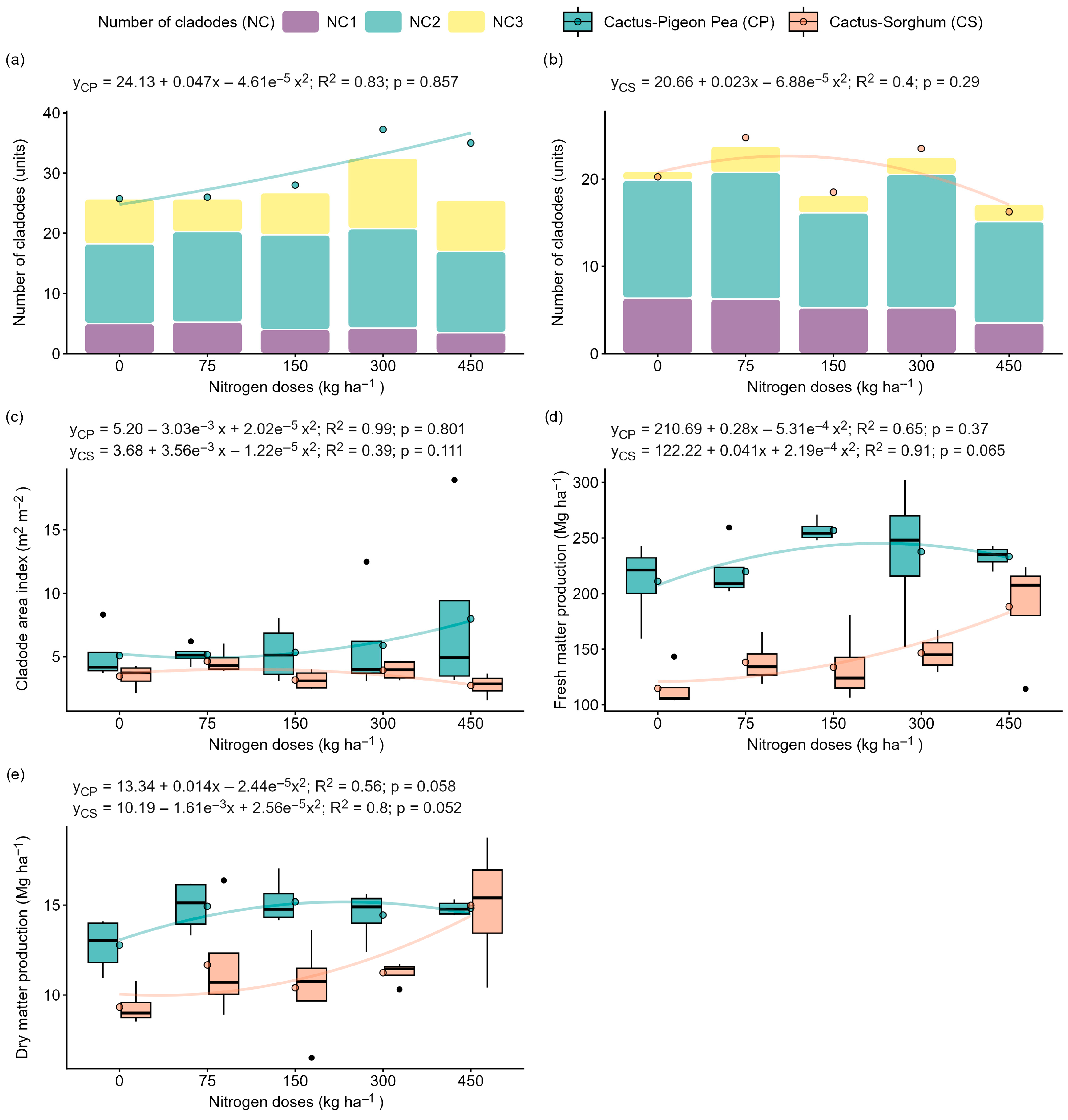

2.1. The Effect of Nitrogen Fertilisation on Growth and Productivity

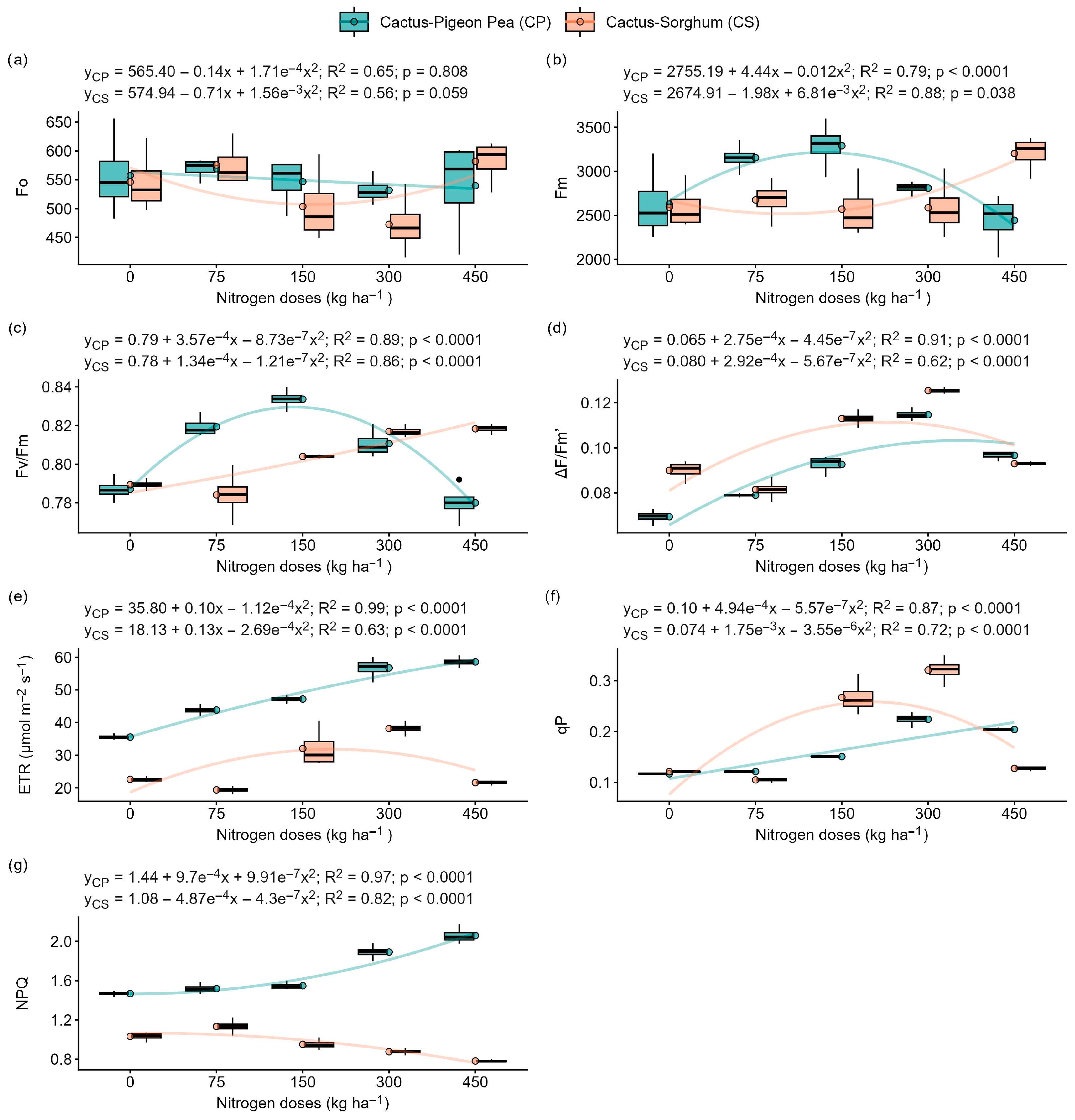

2.2. Effects of Nitrogen Doses and Cultivation Systems on Chlorophyll a Fluorescence

2.3. Measurement of the Physiological Responses

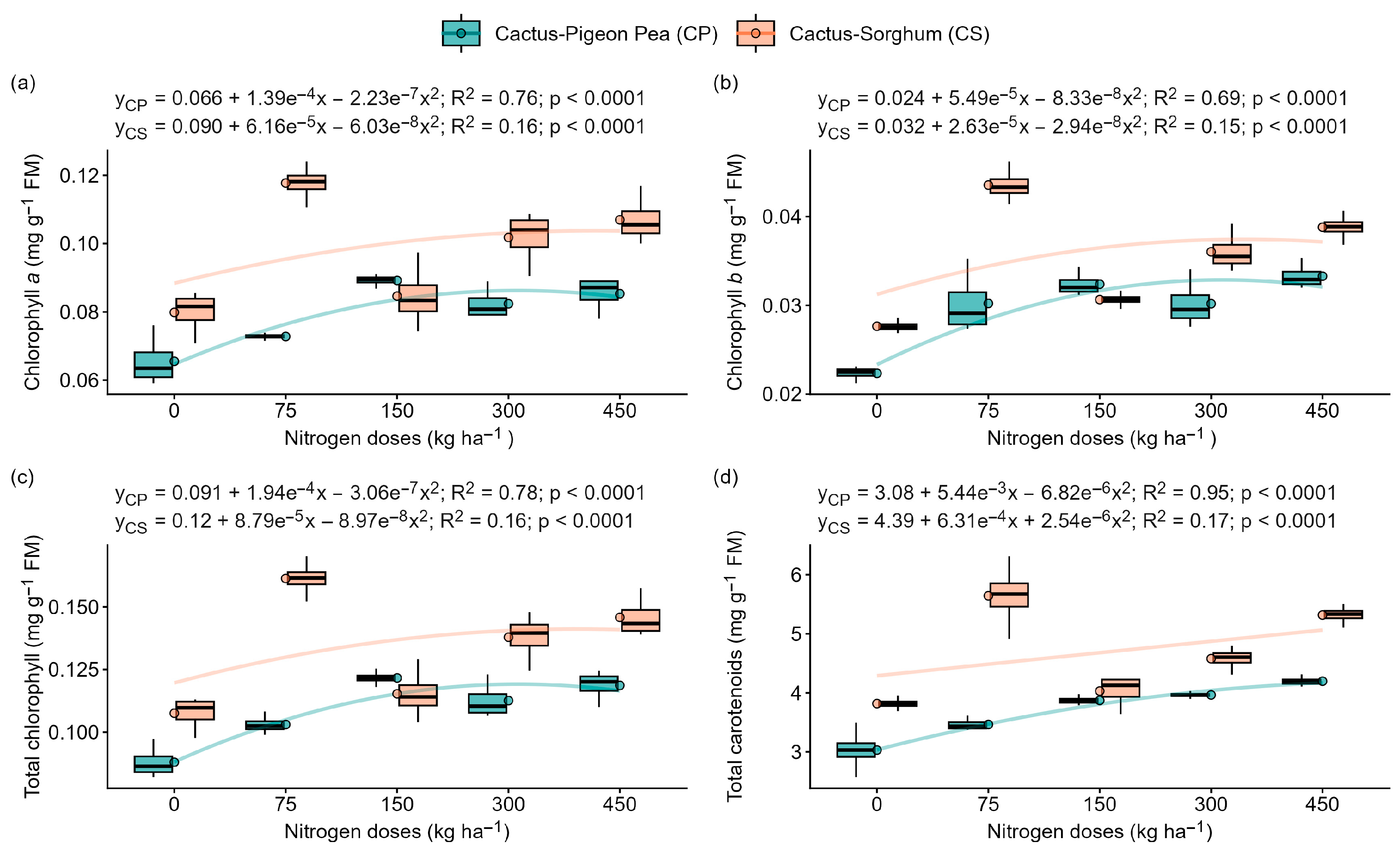

2.4. Effect of Nitrogen Application and Intercropping on Photosynthetic Pigment Content

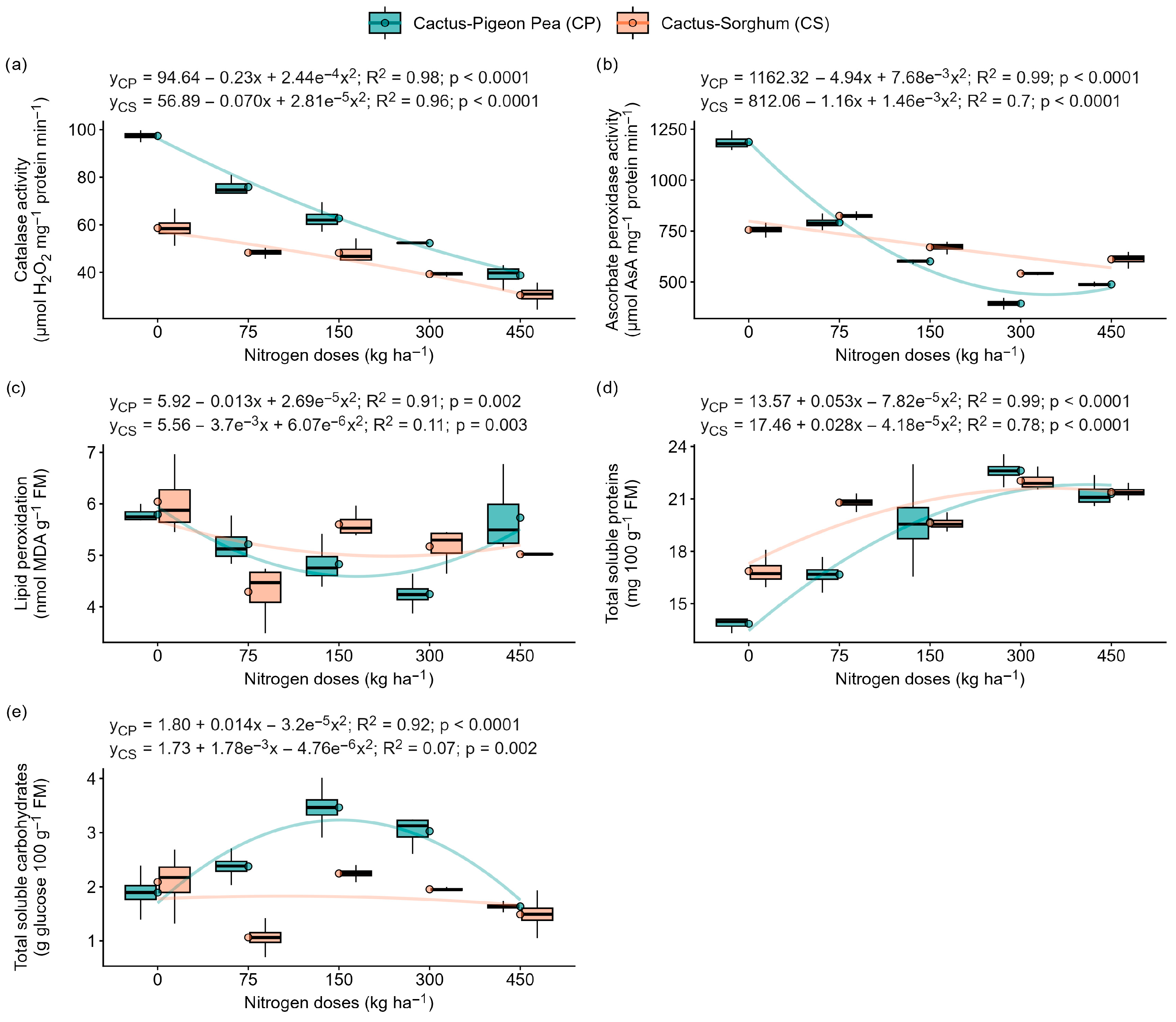

2.5. Lipid Peroxidation, Enzyme Activity and Protein and Carbohydrate Content

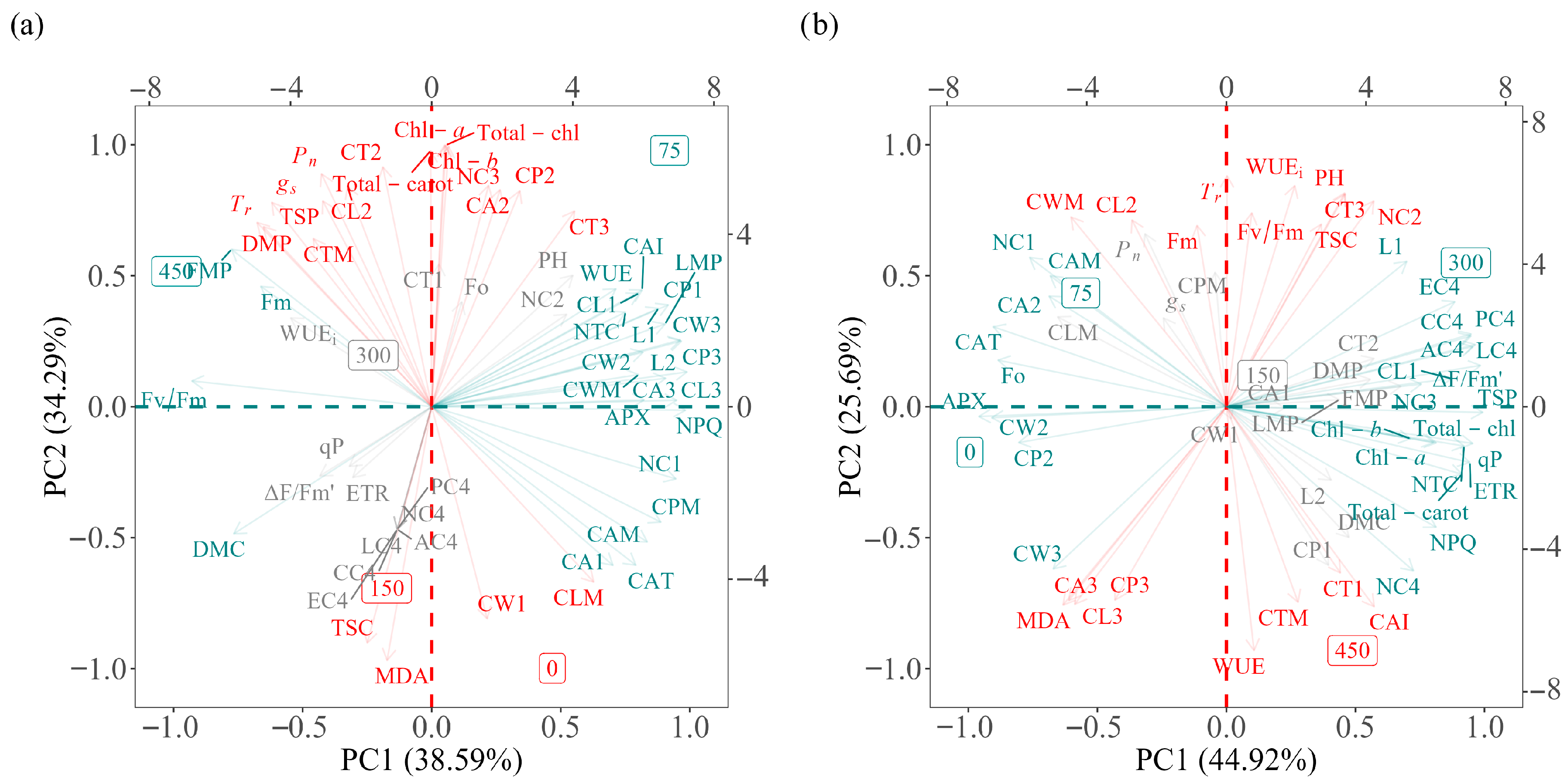

2.6. Association Between Variables Using Principal Component Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. Productive Performance of the Forage Cactus Is Optimised by Moderate Nitrogen Doses in Intercropping Arrangements

3.2. Nitrogen Deficiency Intensifies Photoinhibition and Compromises Photosynthesis

3.3. Nitrogen Supply Strengthens the Antioxidant System and Reduces Oxidative Damage

3.4. Multivariate Integration of Productive and Physiological Parameters

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Characterisation of the Study Area

4.2. Experimental Design, Treatments and Irrigation Management

4.3. Evaluating Growth and Productivity

4.4. Measurements of Gas Exchange

4.5. Chlorophyll Fluorescence

4.6. Biochemical Evaluations

4.7. Chlorophyll a and b and Total Carotenoids

4.8. Total Soluble Carbohydrates and Lipid Peroxidation

4.9. Enzyme Extraction and Assay

4.10. Total Soluble Proteins (TSP), Catalase (CAT) and Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) Activity

4.11. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mu, X.; Chen, Y. The Physiological Response of Photosynthesis to Nitrogen Deficiency. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Santos, H.R.B.; Alves, H.K.M.N.; Ferreira-Silva, S.L.; de Souza, L.S.B.; Júnior, G.D.N.A.; de Sá Souza, M.; de Araújo, G.G.L.; de Souza, C.A.A.; da Silva, T.G.F. Genotypic Differences Relative Photochemical Activity, Inorganic and Organic Solutes and Yield Performance in Clones of the Forage Cactus under Semi-Arid Environment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, N.; Kirst, M.; Chen, S. Bringing CAM Photosynthesis to the Table: Paving the Way for Resilient and Productive Agricultural Systems in a Changing Climate. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cushman, J.C.; Borland, A.M.; Edwards, E.J.; Wullschleger, S.D.; Tuskan, G.A.; Owen, N.A.; Griffiths, H.; Smith, J.A.C.; De Paoli, H.C.; et al. A Roadmap for Research on Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) to Enhance Sustainable Food and Bioenergy Production in a Hotter, Drier World. New Phytol. 2015, 207, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-González, Á.J.; Medina-De la Rosa, G.; Bautista, E.; Flores, J.; López-Lozano, N.E. Physiological Regulations of a Highly Tolerant Cactus to Dry Season Modify Its Rhizospheric Microbial Communities. Rhizosphere 2023, 25, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.P.; Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Júnior, G.D.N.A.; de Souza, L.S.B.; de Araújo, G.G.L.; de Souza, C.A.A.; da Silva Salvador, K.R.; Leite, R.M.C.; Pinheiro, A.G.; da Silva, T.G.F. How to Enhance the Agronomic Performance of Cactus-Sorghum Intercropped System: Planting Configurations, Density and Orientation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 184, 115059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.D.; de Matos, R.M.; da Silva, P.F.; de Lima, A.S.; de Azevedo, C.A.V.; Saboya, L.M.F. Growth and Yield of Cactus Pear under Irrigation Frequencies and Nitrogen Fertilization. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2020, 24, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Santos, J.P.A.; de Oliveira, A.C.; de Morais, J.E.F.; Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Alves, C.P.; Júnior, G.D.N.A.; de Souza, C.A.A.; da Silva, M.J.; de Souza, L.F.; de Souza, L.S.B.; et al. Morphophysiological Responses, Water, and Nutritional Performance of the Forage Cactus Submitted to Different Doses of Nitrogen. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 308, 109273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Sun, H.; Shao, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Long, H.; Geng, X.; Zhang, Y. Progress in the Study of Plant Nitrogen and Potassium Nutrition and Their Interaction Mechanisms. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.G.F.; de Medeiros, R.S.; Arraes, F.D.D.; Ramos, C.M.C.; Júnior, G.D.N.A.; Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Alves, C.P.; Campos, F.S.; da Silva, M.V.; de Morais, J.E.F.; et al. Cactus–Sorghum Intercropping Combined with Management Interventions of Planting Density, Row Orientation and Nitrogen Fertilisation Can Optimise Water Use in Dry Regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 165102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.N.; Cândido, M.J.D.; Gomes, G.M.F.; Maranhão, T.D.; da Costa Gomes, E.; Soares, I.; Pompeu, R.C.F.F.; da Silva, R.G. Forage Biomass and Water Storage of Cactus Pear under Different Managements in Semi-Arid Conditions. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2021, 50, e20210022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas Campos, A.R.; Pereira da Silva, A.J.; de Jong van Lier, Q.; Lima do Nascimento, F.A.; Miranda Fernandes, R.D.; Nunes de Almeida, J.; Pedro da Silva Paz, V. Yield and Morphology of Forage Cactus Cultivars under Drip Irrigation Management Based on Soil Water Matric Potential Thresholds. J. Arid. Environ. 2021, 193, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Louhaichi, M.; Dana Ram, P.; Tirumala, K.K.; Ahmad, S.; Rai, A.K.; Sarker, A.; Hassan, S.; Liguori, G.; Probir Kumar, G.; et al. Cactus Pear (Opuntia Ficus-Indica) Productivity, Proximal Composition and Soil Parameters as Affected by Planting Time and Agronomic Management in a Semi-Arid Region of India. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Coêlho, D.; Dubeux, J.C.B.; dos Santos, M.V.F.; de Mello, A.C.L.; da Cunha, M.V.; dos Santos, D.C.; de Freitas, E.V.; da Silva Santos, E.R. Soil and Root System Attributes of Forage Cactus under Different Management Practices in the Brazilian Semiarid. Agronomy 2023, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Han, L.; Xu, N.; Sun, M.; Yang, X. Nitrate Nitrogen Enhances the Efficiency of Photoprotection in Leymus Chinensis under Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1348925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.S.; Andrade, A.N.; Dantas, E.F.O.; Soares, V.A.; Araujo, D.J.; Santos, S.K.; Lopes, A.S.; Ribeiro, J.E.S.; Ferreira, V.C.S.; Henschel, J.M.; et al. Drought-Induced Changes in Antioxidant Capacity, Mineral Content, and Plant Development in Basal Leafy Cactus: Comparisons between Pereskia Aculeata Miller and Pereskia Bahiensis Gürke. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 309, 154503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, J.P.A.; Neto, M.C.L.; da Silva Brito, N.D.; Herminio, P.J.; Santos, H.R.B.; Simões, A.D.N.; Nunes, V.G.; de Lima, A.L.A.; de Souza, E.S.; Ferreira-Silva, S.L. The C3-CAM Shift Is Crucial to the Maintenance of the Photosynthetic Apparatus Integrity in Pereskia Aculeata under Prolonged and Severe Drought. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2024, 46, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Xu, M.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, L.T. Effects of Nitrogen Deficiency on the Photosynthesis, Chlorophyll a Fluorescence, Antioxidant System, and Sulfur Compounds in Oryza Sativa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, F.M.; Dubeux, J.C.B.; da Cunha, M.V.; Menezes, R.S.C.; dos Santos, M.V.F.; Camelo, D.; Ferraz, I. Performance of Forage Cactus Intercropped with Arboreal Legumes and Fertilized with Different Manure Sources. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Salvador, K.R.; Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Alves, C.P.; Júnior, G.D.N.A.; da Silva, M.J.; de Souza, L.F.; Queiroz, M.A.Á.; Campos, F.S.; Gois, G.C.; de França, J.G.E.; et al. Intercropping Impacts Growth in the Forage Cactus, but Complementarity Affords Greater Productivity, Competitive Ability, Biological Efficiency and Economic Return. Agric. Syst. 2024, 218, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Alves, R.; Felix, E.D.S.; de Oliveira Filho, T.J.; Lira, E.C.; Lima, R.P.; Costa, M.D.P.S.D.; de Araújo Oliveira, J.; Souza, J.T.A.; Pereira, E.M.; Gratão, P.L.; et al. Antioxidant Metabolism in Forage Cactus Genotypes Intercropped with Gliricidia Sepium in a Semi-Arid Environment. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2024, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homulle, Z.; George, T.S.; Karley, A.J. Root Traits with Team Benefits: Understanding Belowground Interactions in Intercropping Systems. Plant Soil 2021, 471, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-P.; Surigaoge, S.; Yang, H.; Yu, R.-P.; Wu, J.-P.; Xing, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.-P.; Surigaoge, S.; et al. Diversified Cropping Systems with Complementary Root Growth Strategies Improve Crop Adaptation to and Remediation of Hostile Soils. Plant Soil 2024, 502, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Nasar, J.; Dong, S.; Feng, G.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Q. Deciphering Nitrogen Stress Responses in Maize Rhizospheres: Comparative Transcriptomics of Monocropping and Intercropping Systems. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Chen, Q.; Chen, F.; Yuan, L.; Mi, G. A RNA-Seq Analysis of the Response of Photosynthetic System to Low Nitrogen Supply in Maize Leaf. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Pérez, Z.Z.; Jiménez-Bremont, J.F.; Delgado-Sánchez, P. Continuous High and Low Temperature Induced a Decrease of Photosynthetic Activity and Changes in the Diurnal Fluctuations of Organic Acids in Opuntia Streptacantha. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Ding, P.; Ren, A.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer on Photosynthetic Characteristics and Yield. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yin, W.; Fan, H.; Fan, Z.; Hu, F.; Yu, A.; Zhao, C.; Chai, Q.; Aziiba, E.A.; Zhang, X. Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Water and Nitrogen Coupling for Enhanced High-Density Tolerance and Increased Yield of Maize in Arid Irrigation Regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 726568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomska, E.; Borland, A.M. Crassulacean Acid Metabolism: A Cause or Consequence of Oxidative Stress in Planta? In Progress in Botany; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 247–266. ISBN 978-3-540-72954-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nobel, P.S.; Bobich, E.G. Initial Net CO2 Uptake Responses and Root Growth for a CAM Community Placed in a Closed Environment. Ann. Bot. 2002, 90, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahbouki, S.; Fernando, A.L.; Rodrigues, C.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Ait-El-Mokhtar, M.; Outzourhit, A.; Meddich, A. Effects of Humic Substances and Mycorrhizal Fungi on Drought-Stressed Cactus: Focus on Growth, Physiology, and Biochemistry. Plants 2023, 12, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y. Nitrogen Demand Disparities and Physiological Responses in Grapevine Cultivars under Contrasting Nitrogen Regimes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 227, 110146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M.; Sathish, M.; Kiran, R.; Mushtaq, A.; Baazeem, A.; Hasnain, A.; Hakim, F.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Mubeen, M.; Iftikhar, Y.; et al. Plant Nitrogen Metabolism: Balancing Resilience to Nutritional Stress and Abiotic Challenges. Phyton Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.M.F.; Cândido, M.J.D.; Lopes, M.N.; Maranhão, T.D.; de Andrade, D.R.; Costa, J.F.M.; Silveira, W.M.; Neiva, J.N.M. Chemical Composition of Cactus Pear Cladodes under Different Fertilization and Harvesting Managements. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2018, 53, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; De Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s Climate Classification Map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotraspiration Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998; Volume 300, p. D05109. ISBN 9251042195. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, L.A. Diagnosis and Improvement. Saline and Alkali Soils 1954, 60, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; da Silva, T.G.F.; de Souza, L.S.B.; de Sá Souza, M.; de Morais, J.E.F.; Júnior, G.D.N.A. Multivariate Analysis in the Morpho-Yield Evaluation of Forage Cactus Intercropped with Sorghum. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2020, 24, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, K.M.; da Silva, T.G.F.; da Silva Diniz, W.J.; de Sousa Carvalho, H.F.; de Moura, M.S.B. Indirect Methods for Determining the Area Index of Forage Cactus Cladodes. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2015, 45, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.; Miranda, K.; Santos, D.; Queiroz, M.; Silva, M.; Neto, J.C.; Araújo, J. Area Do Cladódio De Clones De Palma Forrageira: Modelagem, Análise E Aplicabilidade. Rev. Bras. Ciencias Agrar. 2014, 9, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV-VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3.1–F4.3.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho Júnior, L.F.; Ferreira-Silva, S.L.; Vieira, M.R.S.; Carnelossi, M.A.G.; Simoes, A.N. Darkening, Damage and Oxidative Protection Are Stimulated in Tissues Closer to the Yam Cut, Attenuated or Not by the Environment. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak, I.; Strbac, D.; Marschner, H. Activities of Hydrogen Peroxide-Scavenging Enzymes in Germinating Wheat Seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 1993, 44, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havir, E.A.; McHale, N.A. Biochemical and Developmental Characterization of Multiple Forms of Catalase in Tobacco Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide Is Scavenged by Ascorbate-Specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Experiment | Nitrogen Dose (kg ha−1) | Equation | R2 | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 75 | 150 | 300 | 450 | |||||

| PH (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 96.8 | 99.5 | 103.5 | 105.3 | 94.8 | y = 95.70 + 0.084x − 1.88e−4x2 | 0.93 | 0.63 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 72.0 | 86.3 | 80.5 | 78.8 | 72.8 | y = 75.42 + 0.072x − 79e−4x2 | 0.55 | 0.11 | |

| PW (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 62.0 | 64.6 | 52.6 | 73.0 | 68.0 | y = 59.88 + 0.021x | 0.26 | 0.75 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 53.8 | 62.6 | 50.0 | 55.1 | 44.8 | y = 57.80 − 0.023x | 0.41 | 0.00 | |

| CL1 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 28.3 | 27.5 | 30.8 | 31.6 | 29.8 | y = 27.42 + 0.026x − 4.42e−5x2 | 0.68 | 0.51 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 31.3 | 33.3 | 31.3 | 32.1 | 30.3 | y = 31.63 + 7.86e−3x − 2.41e−5x2 | 0.48 | 0.90 | |

| CL2 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 27.3 | 31.6 | 27.3 | 28.0 | 25.8 | y = 29.21 − 6.35e−3x | 0.27 | 0.43 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 23.8 | 29.6 | 27.6 | 30.1 | 29.6 | y = 24.86 + 0.035x − 5.54e−5x2 | 0.68 | 0.37 | |

| CL3 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 29.5 | 26.5 | 27.9 | 23.3 | 29.0 | y = 29.82−0.041x + 8.39e−5x2 | 0.61 | 0.75 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 18.8 | 22.6 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 12.3 | y = 20.62 − 0.017x | 0.68 | 0.52 | |

| CLM (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 21.3 | 21.0 | 17.5 | 19.6 | 18.3 | y = 20.63 − 5.65e−3x | 0.38 | 0.83 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 25.3 | 21.0 | 21.5 | 17.8 | 18.0 | y = 23.62 − 0.015x | 0.78 | 0.06 | |

| CW1 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 21.3 | 19.9 | 31.0 | 19.3 | 21.3 | y = 21.36 + 0.031x − 7.67e−5x2 | 0.15 | 0.44 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 22.5 | 19.6 | 21.1 | 18.8 | 20.0 | y = 22.14 − 0.020x + 3.26e−5x2 | 0.61 | 0.81 | |

| CW2 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 18.1 | 18.8 | 17.3 | 15.3 | 16.8 | y = 18.25 − 5.27e−3x | 0.50 | 0.39 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 16.1 | 18.0 | 16.5 | 15.0 | 15.1 | y = 17.07 − 4.71e−3x | 0.49 | 0.72 | |

| CW3 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 20.5 | 18.5 | 19.6 | 16.5 | 19.5 | y = 20.62−0.023x + 4.48e−5x2 | 0.57 | 0.74 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 14.4 | 18.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 10.0 | y = 15.86 − 0.013x | 0.57 | 0.49 | |

| CWM (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 27.1 | 28.0 | 24.3 | 26.0 | 22.3 | y = 27.52 − 0.010x | 0.64 | 0.31 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 27.0 | 28.8 | 26.8 | 28.3 | 24.3 | y = 27.06 + 0.014x − 4.41e−5x2 | 0.69 | 0.53 | |

| CT1 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 20.6 | 26.5 | 34.8 | 23.8 | 40.0 | y = 23.26 + 0.030x | 0.46 | 0.30 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 21.8 | 25.0 | 19.5 | 18.0 | 25.8 | y = 23.98 − 0.043x + 1.01e−4x2 | 0.48 | 0.60 | |

| CT2 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 15.6 | 16.0 | 13.5 | 20.0 | 17.0 | y = 15.14 + 6.59e−3x | 0.25 | 0.39 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 13.0 | 15.8 | 13.5 | 14.0 | 16.0 | y = 13.68 + 3.97e−3x | 0.28 | 0.57 | |

| CT3 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 12.0 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 13.5 | 12.3 | y = 12.12 + 0.011x − 2.35e−5x2 | 0.70 | 0.94 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 5.3 | 11.3 | 6.0 | 8.8 | 5.8 | y = 6.53 + 0.021x − 5.11e−5x2 | 0.23 | 0.32 | |

| CTM (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 31.8 | 32.3 | 30.5 | 32.0 | 35.5 | y = 32.17−0.015x + 5.02e−5x2 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 43.8 | 45.3 | 45.0 | 44.3 | 46.0 | y = 44.27 + 2.99e−3x | 0.38 | 0.99 | |

| CP1 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 75.3 | 59.5 | 74.0 | 74.0 | 78.3 | y = 68.34 + 0.020x | 0.24 | 0.05 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 78.5 | 85.5 | 76.3 | 78.0 | 73.5 | y = 81.44 − 0.016x | 0.41 | 0.63 | |

| CP2 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 69.3 | 69.0 | 61.0 | 62.3 | 65.3 | y = 70.26 − 0.064x + 1.17e−4x2 | 0.74 | 0.37 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 58.8 | 75.3 | 65.3 | 69.0 | 64.5 | y = 62.56 + 0.068x − 1.46e−4x2 | 0.30 | 0.47 | |

| CP3 (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 75.0 | 62.5 | 74.0 | 55.3 | 74.0 | y = 75.10 − 0.11x + 2.35e−4x2 | 0.37 | 0.44 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 49.5 | 63.5 | 41.0 | 42.5 | 32.8 | y = 55.27 − 0.048x | 0.57 | 0.39 | |

| CPM (cm) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 51.3 | 55.3 | 45.5 | 55.0 | 49.3 | y = 51.75 − 2.59e−3x | 0.01 | 0.76 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 61.3 | 57.5 | 54.0 | 50.3 | 45.3 | y = 60.31 − 0.034x | 0.98 | 0.13 | |

| CA1 (cm2) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 419.5 | 385.7 | 670.9 | 433.8 | 446.0 | y = 410.62 + 1.10x − 2.4e−3x2 | 0.23 | 0.38 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 491.2 | 465.2 | 471.7 | 425.4 | 423.8 | y = 485.49 − 0.15x | 0.87 | 0.96 | |

| CA2 (cm2) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 344.1 | 420.4 | 329.4 | 303.1 | 301.4 | y = 375.05 − 0.18x | 0.46 | 0.25 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 273.4 | 381.2 | 324.6 | 316.9 | 324.9 | y = 304.80 + 0.31x − 6.38e−4x2 | 0.15 | 0.80 | |

| CA3 (cm2) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 423.4 | 360.3 | 386.5 | 298.5 | 407.6 | y = 428.11 − 0.82x + 1.67e−3x2 | 0.64 | 0.82 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 194.1 | 232.9 | 187.8 | 184.6 | 122.3 | y = 219.73 − 0.18x | 0.68 | 0.81 | |

| MCA (cm2) | Cactus–pigeon pea | 410.3 | 416.9 | 304.3 | 360.5 | 299.1 | y = 402.45 − 0.23x | 0.53 | 0.65 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 479.9 | 424.9 | 400.7 | 353.1 | 311.7 | y = 462.86 − 0.35x | 0.97 | 0.24 | |

| DMC | Cactus–pigeon pea | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | y = 0.060 + 1.4e−5x | 0.25 | 0.45 |

| Cactus–Sorghum | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | y = 0.072 + 2.34e−5x | 0.25 | 0.63 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martins, L.D.C.d.S.; Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Santos, W.M.d.; Morais, J.E.F.d.; Souza, L.S.B.d.; Silva, L.R.d.L.e.; Souza, P.P.S.d.; Santos, A.R.M.d.; Santos, W.R.d.; Alves, C.P.; et al. Nitrogen Fertilisation Modulates Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidant Defence Mechanisms in Intercropped Cactus Under Semi-Arid Conditions. Plants 2025, 14, 3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243841

Martins LDCdS, Jardim AMdRF, Santos WMd, Morais JEFd, Souza LSBd, Silva LRdLe, Souza PPSd, Santos ARMd, Santos WRd, Alves CP, et al. Nitrogen Fertilisation Modulates Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidant Defence Mechanisms in Intercropped Cactus Under Semi-Arid Conditions. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243841

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins, Lady Daiane Costa de Sousa, Alexandre Maniçoba da Rosa Ferraz Jardim, Wagner Martins dos Santos, José Edson Florentino de Morais, Luciana Sandra Bastos de Souza, Lara Rosa de Lima e Silva, Pedro Paulo Santos de Souza, Agda Raiany Mota dos Santos, Wilma Roberta dos Santos, Cleber Pereira Alves, and et al. 2025. "Nitrogen Fertilisation Modulates Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidant Defence Mechanisms in Intercropped Cactus Under Semi-Arid Conditions" Plants 14, no. 24: 3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243841

APA StyleMartins, L. D. C. d. S., Jardim, A. M. d. R. F., Santos, W. M. d., Morais, J. E. F. d., Souza, L. S. B. d., Silva, L. R. d. L. e., Souza, P. P. S. d., Santos, A. R. M. d., Santos, W. R. d., Alves, C. P., Silva, E. F. d., Santos, H. R. B., Souza, C. A. A. d., Cruz Neto, J. F. d., Simões, A. N., Ferreira-Silva, S. L., Wang, J., Tang, X., de Lima, J. L. M. P., & Silva, T. G. F. d. (2025). Nitrogen Fertilisation Modulates Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidant Defence Mechanisms in Intercropped Cactus Under Semi-Arid Conditions. Plants, 14(24), 3841. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243841