Assessing the Ecotoxicological Effects of Emerging Drug and Dye Pollutants on Plant–Soil Systems Pre- and Post-Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Problem Statement: Increasing Detection of Pharmaceuticals and Dyes in Soil and Water Environments

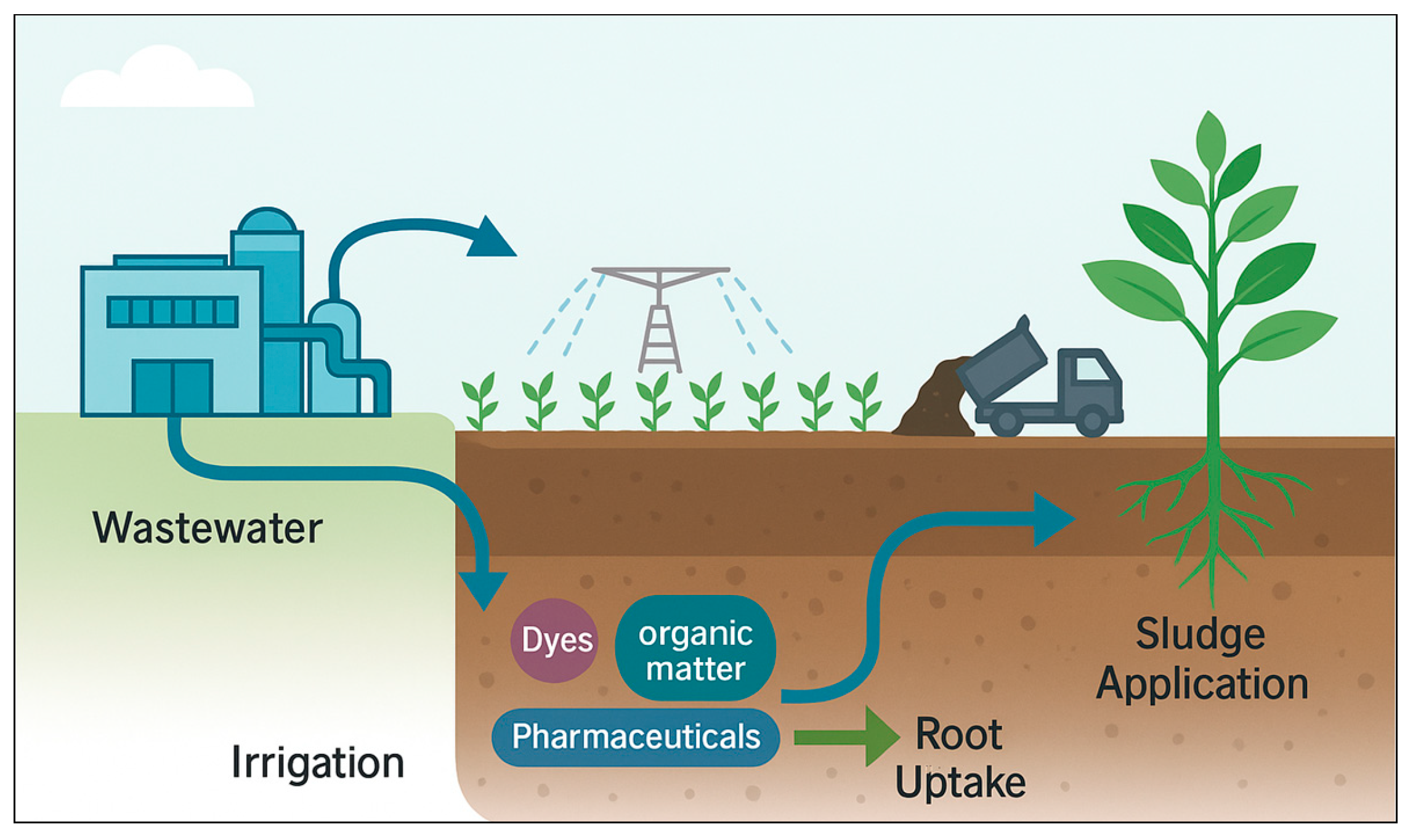

1.2. Environmental Pathways: From Wastewater to Soil and Plant Systems via Irrigation and Sludge Application

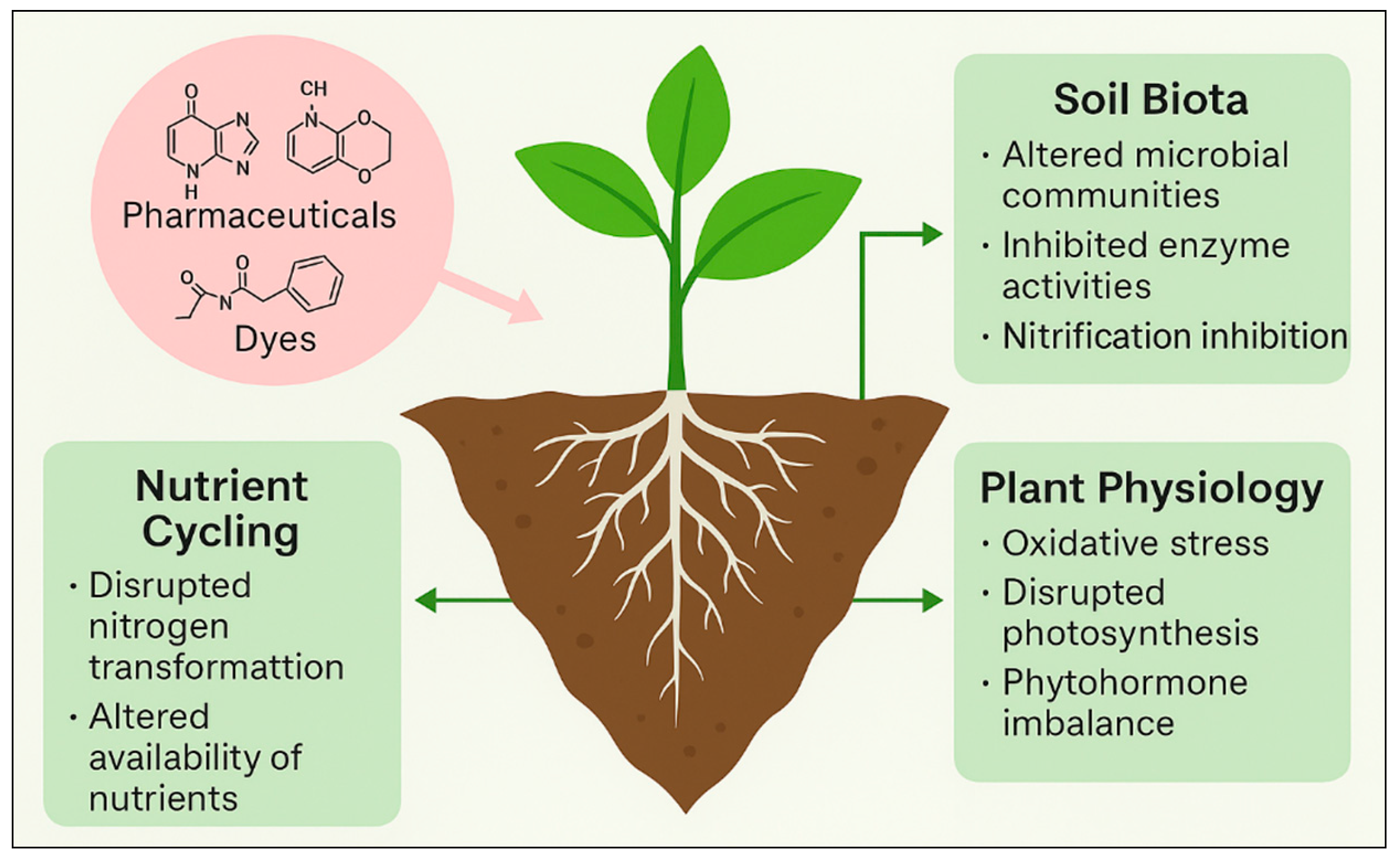

1.3. Relevance for Plant–Soil Health: Impacts on Soil Biota, Nutrient Cycling, and Plant Physiology

1.4. Need for Advanced Treatment: Limitations of Conventional Wastewater Systems and Role of Photocatalysis

1.4.1. Challenges of Conventional Treatments and Advantages of Photocatalytic Approaches for Micropollutant Removal

1.4.2. Operational Limitations and Engineering Advances in Photocatalytic Systems

1.5. Scope and Objectives: Comparative Assessment of Plant–Soil Ecotoxicity Before and After Photocatalytic Degradation

1.6. Methodology

- Literature collection and selection

- 2.

- Screening and categorization

- 3.

- Comparative and critical synthesis

- 4.

- Integration of analytical and ecological insights

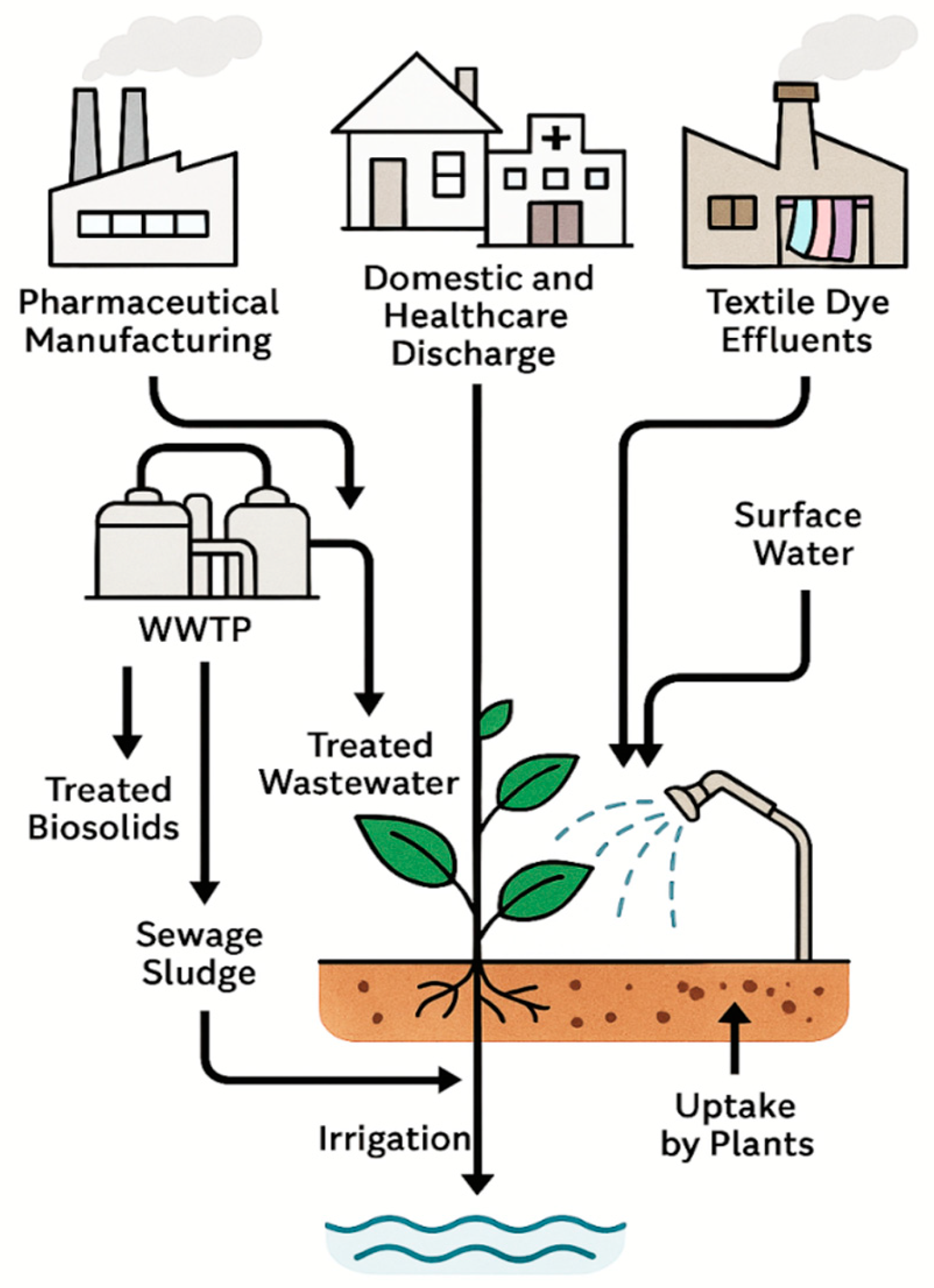

2. Sources, Environmental Fate, and Soil Entry of Emerging Drug and Dye Pollutants

2.1. Sources and Release Pathways

2.1.1. Major Dye Classes and Their Environmental Behaviour

2.1.2. Major Pharmaceutical Classes and Their Environmental Behaviour

2.1.3. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

2.1.4. Domestic and Healthcare Discharge

2.1.5. Textile Dye Effluents

2.1.6. Pathways to Soils and Plants

2.1.7. Integrated Environmental Relevance

2.2. Transport to Soil Systems

2.2.1. Irrigation with Reclaimed Water

2.2.2. Sludge/Biosolid Amendment

2.2.3. Infiltration and Leaching

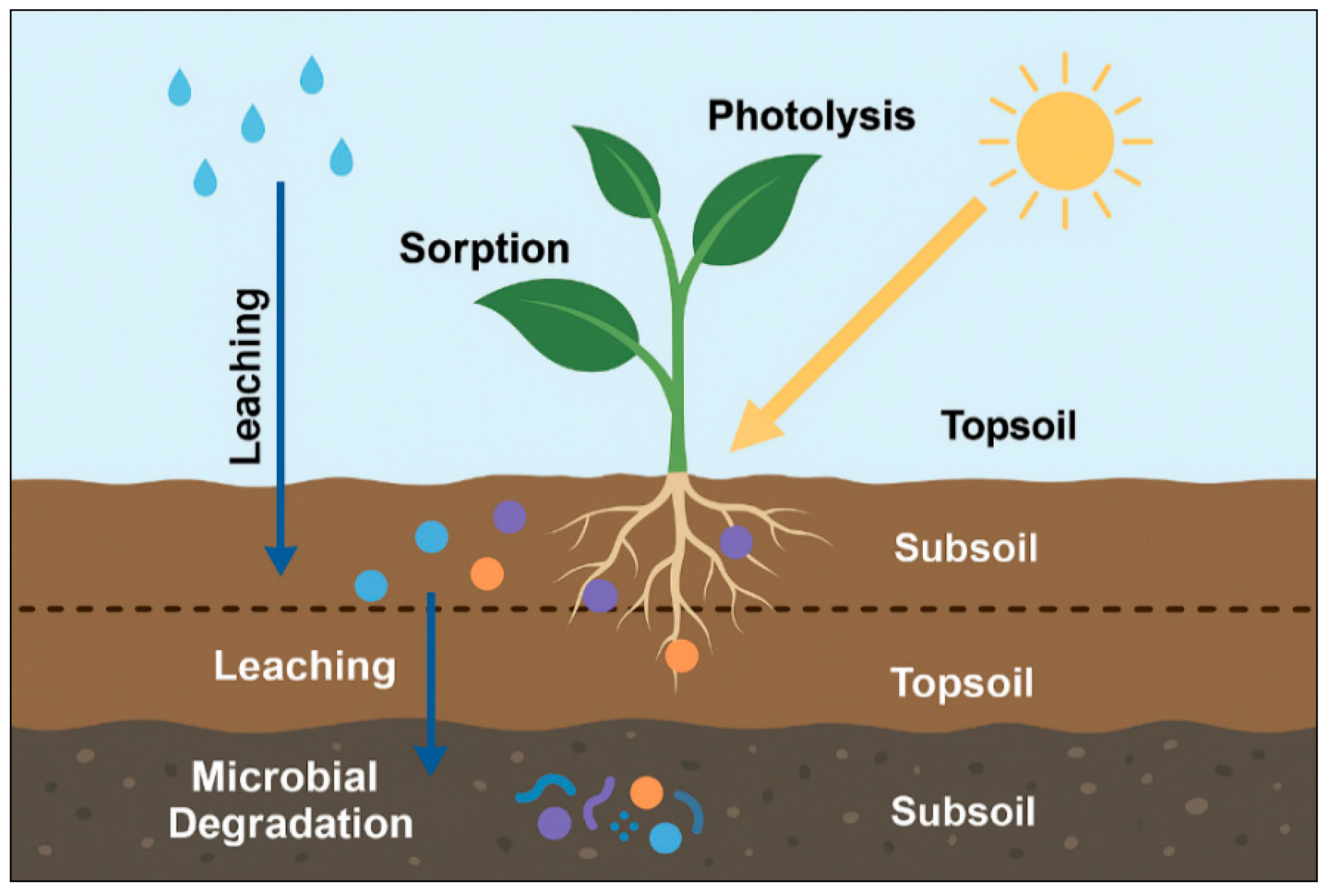

2.3. Chemical Persistence and Mobility

2.3.1. Sorption and Desorption

2.3.2. Leaching and Transport

2.3.3. Photolysis and Abiotic Degradation

2.3.4. Microbial Degradation

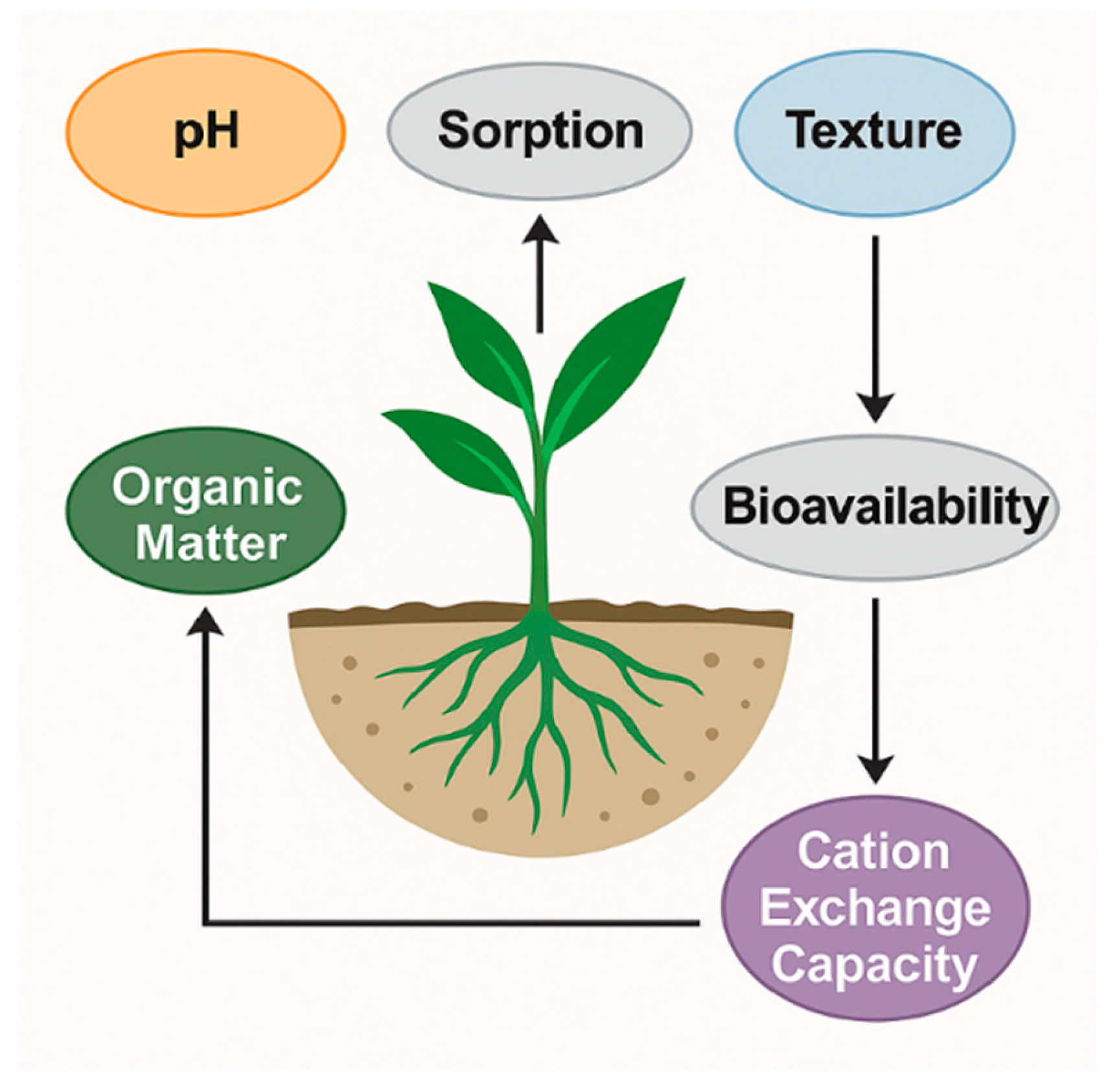

2.4. Influence of Soil Properties—pH, Texture, Organic Matter, and Cation Exchange Capacity Affecting Pollutant Bioavailability

2.4.1. Soil pH

2.4.2. Soil Texture

2.4.3. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

2.4.4. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC)

2.4.5. Integrated Implications for Bioavailability

3. Plant Uptake and Phytotoxicity of Drugs and Dyes in Contaminated Soils

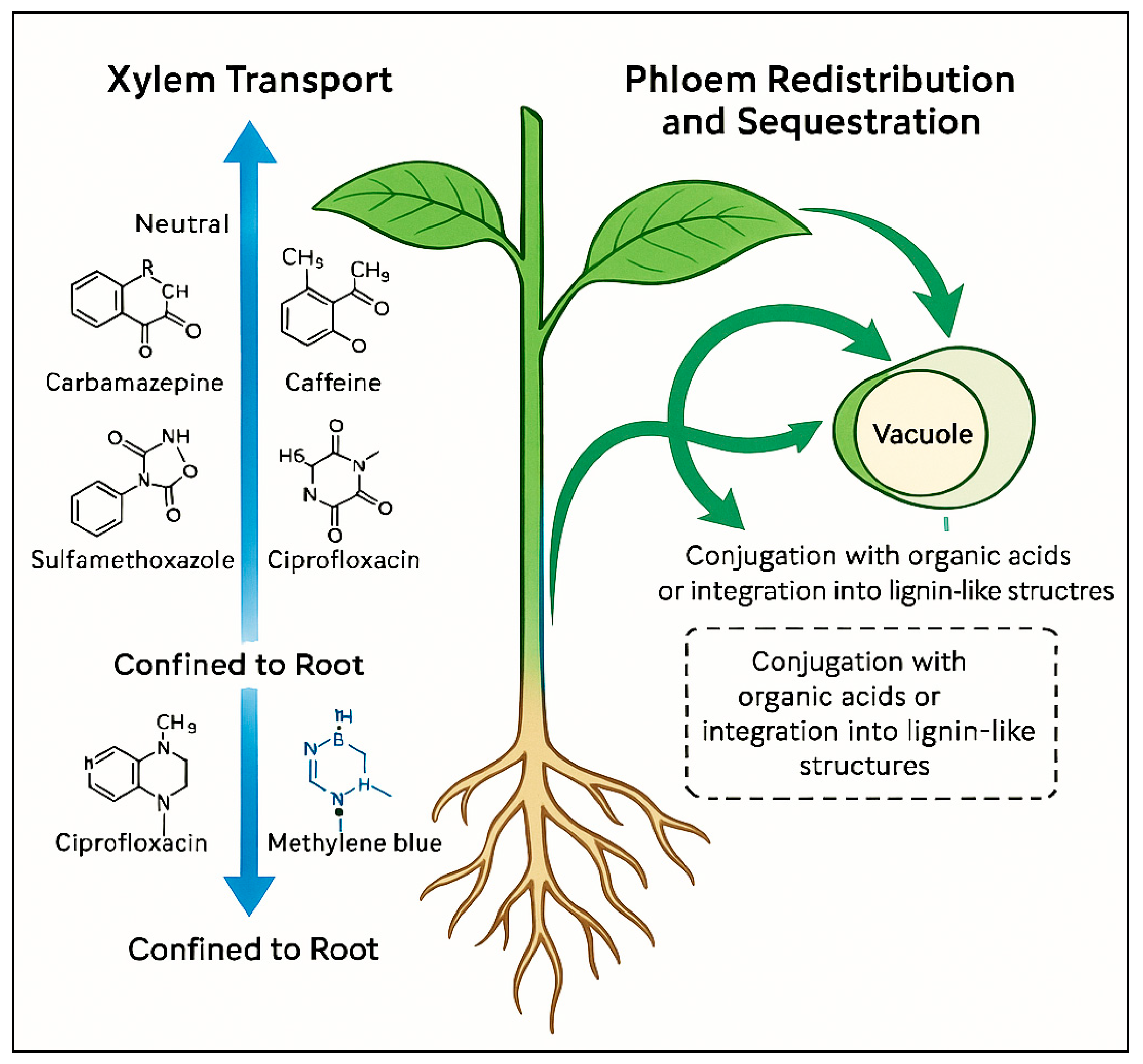

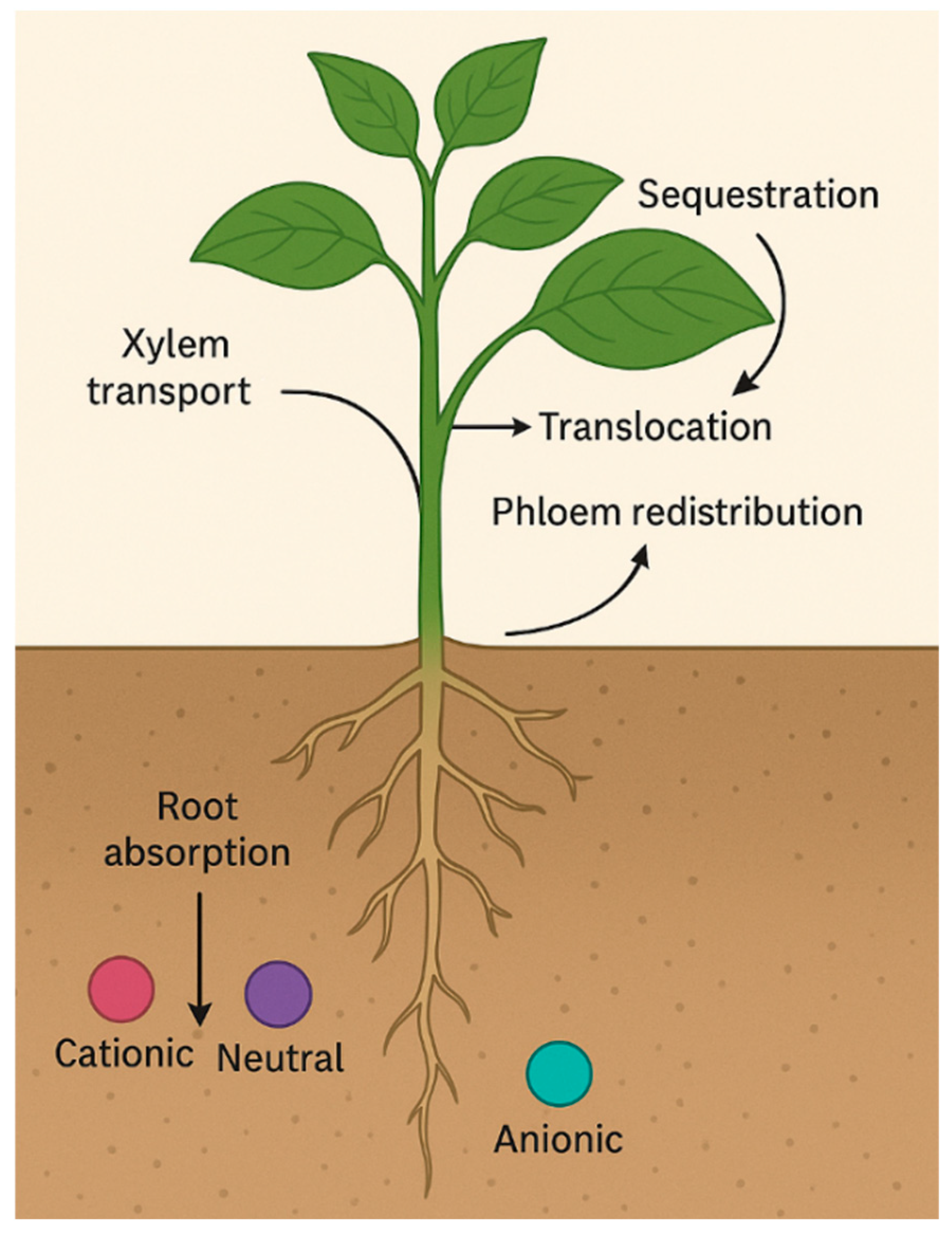

3.1. Uptake Mechanisms—Root Absorption, Xylem Transport, Translocation, and Sequestration

3.1.1. Root Absorption

3.1.2. Xylem Transport and Translocation

3.1.3. Phloem Redistribution and Sequestration

3.1.4. Integrated Dynamics

3.2. Phytotoxicity Endpoints—Germination, Biomass, Pigment Content, Oxidative Stress, Genotoxicity

3.2.1. Seed Germination and Early Growth

3.2.2. Biomass and Morphological Responses

3.2.3. Pigment Content and Photosynthetic Efficiency

3.2.4. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Responses

3.2.5. Genotoxic and Cytological Effects

3.3. Interactions with Soil Microbiota—Indirect Effects Through Microbiome Disruption

3.4. Dose–Response Relationships—Influence of Pollutant Concentration and Exposure Duration

3.4.1. Concentration–Effect Patterns and Thresholds

3.4.2. Hormesis and Low-Dose Stimulation

3.4.3. Exposure Duration and Time-Dependent Toxicity

3.4.4. Mixtures and Interaction Effects

3.4.5. Modeling Implications

3.5. Soil Modulation of Toxicity—Adsorption/Desorption Dynamics and Pollutant Bioavailability

3.5.1. Adsorption Mechanisms and Influencing Factors

3.5.2. Desorption and Bioavailability

3.5.3. Implications for Plant Uptake and Soil Toxicity

3.5.4. Environmental Dynamics and Risk Perspective

4. Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment as a Source Control Strategy

4.1. Principles of Photocatalytic Degradation—ROS Generation, Catalyst Activation, Reaction Pathways

4.1.1. Catalyst Activation and Electron–Hole Generation

4.1.2. ROS Generation and Reactive Pathways

- Catalyst excitation:

- Oxidation reactions:

- Reduction reactions:

4.1.3. Degradation Pathways of Pharmaceuticals and Dyes

4.1.4. Photocatalyst Stability and Reusability

4.2. Photocatalysts and Operational Conditions

4.2.1. TiO2-Based Catalysts

4.2.2. ZnO Photocatalysts

4.2.3. g-C3N4 and Visible-Light Photocatalysis

4.2.4. Doped and Hybrid Photocatalysts

4.2.5. Operational Conditions

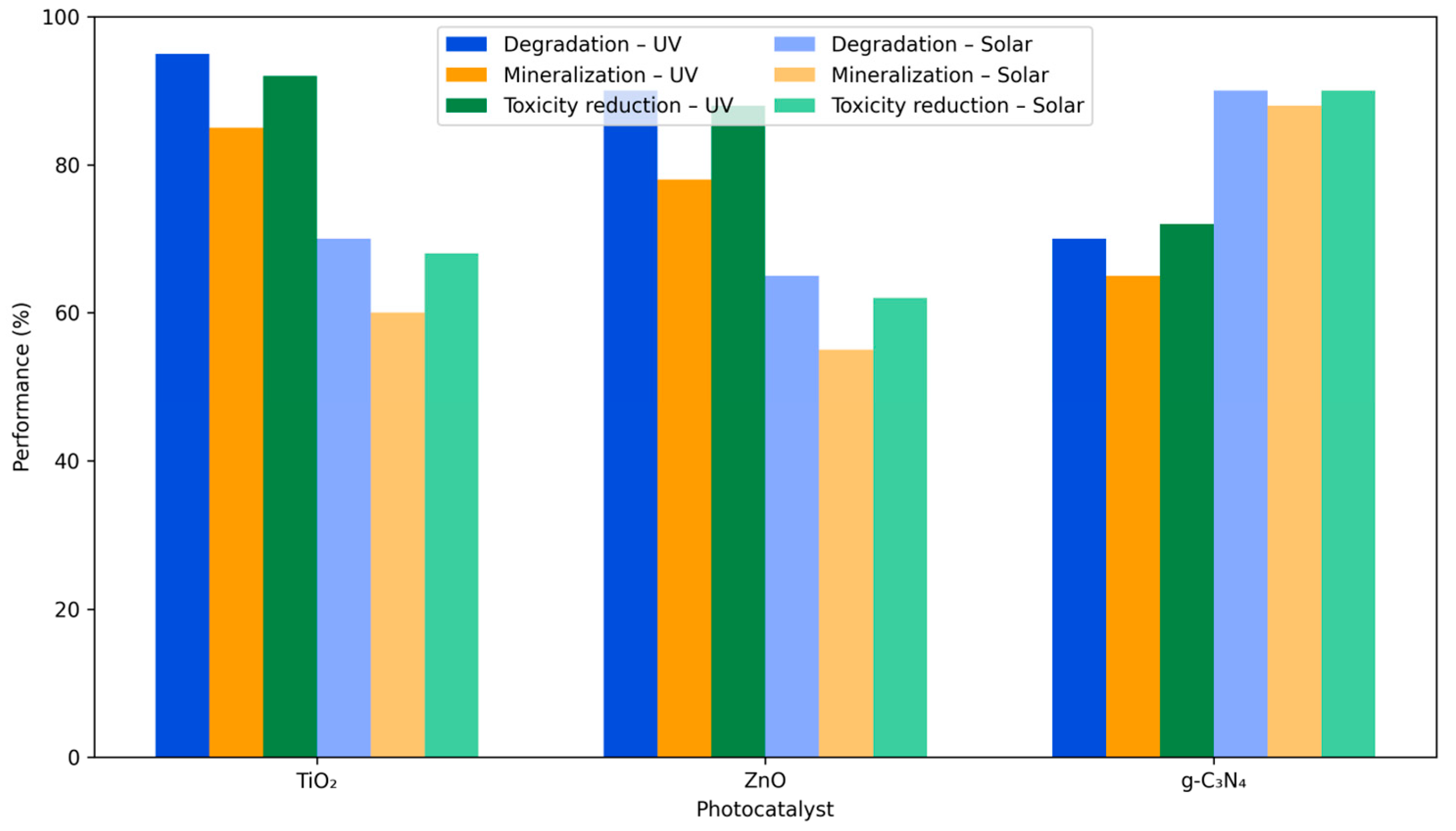

4.3. Performance Metrics—Degradation Rates, Mineralization, and Reduction in Toxicity

4.3.1. Degradation Rates and Kinetic Models

4.3.2. Mineralization Efficiency

4.3.3. Photocatalytic Mineralization Versus Partial Degradation

4.3.4. Reduction in Toxicity and Ecological Safety

4.3.5. Integrated Performance Assessment

4.4. Transformation Product Formation—Mechanisms, Persistence, and Implications for Soil–Plant Exposure

4.4.1. Mechanistic Pathways of Transformation Product Formation

4.4.2. Persistence and Environmental Behavior of Transformation Products

4.4.3. Implications for Soil–Plant Systems and Ecotoxicological Risk

4.4.4. Strategies for TP Management and Risk Mitigation

4.5. Integration of Monitoring Tools and Risk Modeling Metrics (PEC, PNEC, HQ) in AOP Evaluation

5. Post–Photocatalytic Residuals: Transformation Products and Soil–Plant Toxicity

5.1. Classification of Transformation Product (TP) Types

5.1.1. Hydroxylated and Dealkylated Derivatives

5.1.2. Ring-Cleavage Products and Short-Chain Carboxylic Acids

5.1.3. Aromatic Amines and Other Nitrogen-Containing Species

5.1.4. Halogenated and Nitrated Intermediates

5.1.5. Quinone-Type and Other Carbonyl Transformation Products

5.1.6. Ecotoxicologically Relevant Transformation Products: Case Studies

Diclofenac: Formation of ROS-Generating Quinone-Imine Derivatives and Persistent Halogenated Aromatics

Malachite Green: Persistent N-Demethylated Aromatic Intermediates and Ecotoxicologically Relevant Benzophenone-Type TPs

- -

- Planar aromatic structure, enhancing sorption to humic substances and soil particles.

- -

- Photoreactivity, enabling secondary ROS generation under sunlight, thereby prolonging oxidative pressure in exposed plant tissues.

Environmental Implications

5.2. Identification and Characterization of Transformation Products

5.2.1. Analytical Strategies for TP Identification

5.2.2. Transformation Pathways and Chemical Markers

5.2.3. Relevance to Environmental Monitoring and Toxicity

5.3. Fate of TPs in Soils—Sorption, Mobility, and Biodegradability

5.3.1. Sorption Processes and Binding Mechanisms

5.3.2. Mobility and Leaching Dynamics

5.3.3. Biodegradability and Microbial Transformation

5.3.4. Persistence, Aging, and Soil Compartmentalization

5.3.5. Environmental and Agronomic Implications

5.4. Comparative Toxicity to Plants and Soil Organisms—Parent vs. Degraded Compounds

5.4.1. Phytotoxic Responses to Transformation Products

5.4.2. Soil Microbial and Faunal Sensitivity

5.4.3. Mechanistic Insights into Altered Toxicity

5.4.4. Comparative Assessment and Implications for Risk Management

6. Comparative Ecotoxicological Assessment Pre– and Post–Photocatalysis

6.1. Synthesis of Experimental Findings—Summary of Studies Comparing Untreated and Treated Effluents

6.1.1. Experimental Evidence of Detoxification and Transient Toxicity During Photocatalytic Treatment

6.1.2. Endpoints and Sensitivity

6.1.3. Implications for Soil–Plant Systems

6.1.4. Bottom Line

6.2. Quantitative Analysis—Magnitude and Direction of Toxicity Change (Reduction, Persistence, Enhancement)

6.3. Factors Influencing Detoxification Outcomes—Catalyst Type, Water Matrix, Soil Conditions

6.4. Relevance for Agricultural Reuse—Safe Limits for Irrigation and Soil Application

7. Implications for Plant–Soil Health and Environmental Risk Assessment

7.1. Pollutant Accumulation and Soil Functioning—Enzyme Activities, Nutrient Cycling, and Microbial Balance

- Soil enzyme activities

- Nutrient cycling

- Microbial balance and community structure

- Role of transformation products

- Assessment implications

7.2. Risk Assessment Framework—PEC/PNEC Ratios, Hazard Quotients for Parent and Transformation Products

7.3. Food Chain and Crop Safety Concerns—Accumulation in Edible Tissues

7.4. Long-Term Ecological Impacts—Persistence and Cumulative Exposure in Soils

8. Knowledge Gaps and Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, J.L.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Kolpin, D.W.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lai, R.W.S.; Galban-Malagond, C.; Adelle, A.D.; Mondonf, J.; Metiang, M.; Marchant, R.A.; et al. Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113947119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehalt Macedo, H.; Sumpter, J.P.; Richmond, E.; Khan, U.; Klein, E.Y. Antibiotics in the Global River System Arising from Human Activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 4, pgaf096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umweltbundesamt (German Environment Agency). Entry and Occurrence of Human Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. 17 December 2024. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Navarro, S. How Pharmaceutical Residues Occur, Behave, and Affect the Soil Environment. J. Xenobiotics 2024, 14, 1343–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Mordechay, E.; Mordehay, V.; Tarchitzky, J.; Chefetz, B. Pharmaceuticals in Edible Crops Irrigated with Reclaimed Wastewater: Evidence From a Large Survey in Israel. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, J.; Trapp, S.; Garduño-Jiménez, A.; Carter, L. A Framework to assess Pharmaceutical Accumulation in Crops Irrigated with Treated Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 493, 138297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obijianya, C.C.; Yakamercan, E.; Karimi, M.; Veluru, S.; Simko, I. Agricultural Irrigation using treated wastewater: Challenges and Opportunities. Water 2025, 17, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, R.; Bhat, S.V.; Kumar, R. Environmental Risks of Textile Dyes and Photocatalytic Materials for Sustainable Treatment: Current Status and Future Directions. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, D.A.; Scholz, M. Shallow Pond Systems Planted with Lemna minor Treating Azo Dyes. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 94, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P. Recent Advances in the Remediation of Textile-Dye-Containing Wastewater: Prioritizing Human Health and Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.J.; Chefetz, B.; Abdeen, Z.; Boxall, A.B.A. Emerging Investigator Series: Towards a Framework for Establishing the Impacts of Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Irrigation Systems on Agro-Ecosystems and Human Health. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosharaf, M.K.; Gomes, R.L.; Cook, S.; Alam, M.S.; Rasmusssen, A. Wastewater Reuse and Pharmaceutical Pollution in Agriculture: Uptake, Transport, Accumulation and Metabolism of Pharmaceutical Pollutants within Plants. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolesta, W.; Głodniok, M.; Styszko, K. From Sewage Sludge to the Soil—Transfer of Pharmaceuticals: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Guo, M. Soil–Plant Transfer of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs). Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2021, 7, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.; Rajib, M.M.R.; Sarker, U.; Akter, M.; Khan, M.N.E.A.; Khandaker, S.; Khalid, F.; Rahman, G.K.M.M.; Ercisli, S.; Muresan, C.C.; et al. Optimizing Textile Dyeing Wastewater for Tomato Irrigation Through Physiochemical, Plant Nutrient Uses and Pollution Load Index of Irrigated Soil. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mininni, A.N.; Pietrafesa, A.; Calabritto, M.; Di Biase, R.; Brunetti, G.; De Mastro, F.; Murgolo, S.; De Ceglie, C.; Salerno, C.; Dichio, B. Uptake and translocation of pharmaceutically active compounds by olive tree (Olea europaea L.) irrigated with treated municipal wastewater. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1382595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Dong, W.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, F.; Nieto-Delgado, C. Carbamazepine Degradation by Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalyst Ag3PO4/GO: Mechanism and Pathway. Environ. Sci. Ecotech. 2022, 9, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.C.; Babalola, O.O. Metagenomics: A Tool for Exploring Key Microbiome with the Potentials for Improving Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 886987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M. Water, Soil, and Plants Interactions in a Threatened Environment. Water 2021, 13, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, R.; Zahedipour-Sheshglani, P.; Dzingelevičienė, R.; Abbasi, S.; Rees, R.M. Effects of Pharmaceuticals on the Nitrogen Cycle in Water and Soil: A Review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Asiminicesei, D.M.; Fertu, D.I.; Gavrilescu, M. Occurrence and Fate of Emerging Pollutants in Water Environment and Options for Their Removal. Water 2021, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiminicesei, D.-M.; Fertu, D.I.; Gavrilescu, M. Impact of Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment on the Metabolic Profile of Medicinal Plants and Their Therapeutic Potential. Plants 2024, 13, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagoubi, A.; Giannakis, S.; Chamekh, A.; Kharbech, O.; Chouari, R. Influence of Decades-Long Irrigation with Secondary Treated Wastewater on Soil Microbial Diversity, Resistome Dynamics, and Antibiotrophy Development. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotta, V.; Baaloudj, O.; Brienza, M. Risks Associated with Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture: Investigating the Effects of Contaminants in Soil, Plants, and Insects. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1358842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi-Mitoseru, I.-C.; Stoleru, V.; Gavrilescu, M. Integrated Assessment of Pb(II) and Cu(II) Metal Ion Phytotoxicity on Medicago sativa L., Triticum aestivum L., and Zea mays L. Plants: Insights into Germination Inhibition, Seedling Development, and Ecosystem Health. Plants 2023, 12, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garduño-Jimenez, A.-L.; Carter, L.J. Insights into Mode of Action Mediated Responses Following Pharmaceutical Uptake and Accumulation in Plants. Front. Agron. 2024, 5, 1293555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filote, C.; Ros, M.; Hlihor, R.M.; Cozma, P.; Simion, I.M.; Apostol, M.; Gavrilescu, M. Sustainable Application of Biosorption and Bioaccumulation of Persistent Pollutants in Wastewater Treatment: Current Practice. Processes 2021, 9, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil Microorganisms: Their Role in Enhancing Crop Nutrition and Health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, O.F.S.; Palaniandy, P. Occurrence and Removal of Pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 150, 532–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, L.V.; Muthukumaran, S.; Baskaran, S. Recent Advances in Visible Light-Activated Photocatalysts for Degradation of Dyes: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M.; Demnerová, K.; Aamand, J.; Agathos, S.; Fava, F. Emerging Pollutants in the Environment: Present and future Challenges in Biomonitoring, Ecological Risks and Bioremediation. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosini, C.; Poste, E.; Mostachetti, M.; Torretta, V. Pharmaceuticals in Water Cycle: A Review on Risk Assessment and Wastewater and Sludge Treatment. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 1339–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.S.; Peres, J.A.; Li Puma, G. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water and Wastewater Treatment. Water 2021, 13, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ye, L.; Du, B.; Meng, W.; Liu, W.; Su, G. Comprehensive Screening and Occurrence-Removal Assessment of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Wastewater Treatment Plants using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 386, 127201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary Ealias, A.; Meda, G.; Tanzil, K. Recent Progress in Sustainable Treatment Technologies for the Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater: A Review on Occurrence, Global Status and Impact on Biota. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 262, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ok, Y.S.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E.; Tsang, Y.F. Occurrences and Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Drinking Water and Water/Sewage Treatment Plants: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 596–597, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.-H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H. Comprehensive Evaluation of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Typical Highly Urbanized Regions across China. Environ Pollut. 2015, 204, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Li, R. Recent Advances and Perspectives for Solar-Driven Water Splitting using Particulate Photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 3561–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, S.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jin, T.; Wang, M.H. Recent Advances in Photocatalytic Nanomaterials for Environmental Remediation: Strategies, Mechanisms, and Future Directions. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiu, M.; Lutic, D.; Favier, L.; Gavrilescu, M. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis for Advanced Water Treatment: Materials, Mechanisms, Reactor Configurations, and Emerging Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, U.; Spahr, S.; Lutze, H.; Wieland, A.; Rüting, S.; Gernjak, W.; Wenk, J. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water and Wastewater Treatment–Guidance for Systematic Future Research. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiu, M.; Favier, L.; Gavrilescu, M. Photocatalytic Approaches to Treating Mixtures of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Aquatic Environments. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2025, 24, 745–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiu, M.; Favier, L.; Lutic, D.; Hlihor, R.M.; Sergentu, D.C.; Alonzo, V.; Gavrilescu, M. First Insight on the Effective Removal of Pentoxifylline Drug Under Visible-Light-Driven Irradiation with ZnO Catalyst Obtained Via Precipitation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 386, 125420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, D.G.J. Pollution from Drug Manufacturing: Review and Perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2014, 369, 20130571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Agnihotri, S.; Vasundhara, M. Enhanced Solar Light-Driven Photocatalysis of Norfloxacin using Fe-doped TiO2: RSM Optimization, DFT Simulations, and Toxicity Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 47991–48013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidance on Wastewater and Solid Waste Management for Manufacturing of Antibiotics. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240097254 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- USEPA. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Effluent Guidelines. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/eg/pharmaceutical-manufacturing-effluent-guidelines (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Rosen, R. Mass Spectrometry for Monitoring Micropollutants in Water. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.; Fabregat-Safont, D.; Campos-Mañas, M.; Quintana, J.B. Efficient Validation Strategies in Environmental Analytical Chemistry: A Focus on Organic Micropollutants in Water Samples. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 16, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmus, R.; Bagdonaite, I.; de Voogt, P.; van Wezel, A.P.; ter Laak, T.L. Comprehensive Mass Spectrometry Workflows to Systematically Elucidate Transformation Processes of Organic Micropollutants: A Case Study on the Photodegradation of Four Pharmaceuticals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3723–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcanjo, G.S.; Mounteer, A.H.; Bellato, C.R.; da Silva, L.M.M.; Dias, S.H.B.; da Silva, P.R. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis using TiO2 Modified with Hydrotalcite and Iron Oxide under UV–Visible Irradiation for Color and Toxicity Reduction in Secondary Textile Mill Effluent. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 211, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponza, D.T.; Oztekin, R. Effect of Sonication Assisted by Titanium Dioxide and Ferrous Ions on Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Toxicity Removals from a Petrochemical Industry Wastewater in Turkey. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q. Contamination Remediation and Risk Assessment of Four Typical Long-Residual Herbicides: A Timely Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 997, 180169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, I.M.D.; Almeida, C.V.S.; Mascaro, L.H. A Critical Review of Photo-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes to Pharmaceutical Degradation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Márquez, J.J.; Levchuk, I.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Sillanpää, M. A Critical Review on Application of Photocatalysis for Toxicity Reduction of Real Wastewaters. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej-Knysak, D.; Adamek, E.; Baran, W. Biodegradation of Photocatalytic Degradation Products of Sulfonamides: Kinetics and Identification of Intermediates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollinger, H. Color Chemistry: Syntheses, Properties, and Applications of Organic Dyes and Pigments, 3rd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, T.; McMullan, G.; Marchant, R.; Nigam, P. Remediation of Dyes in Textile Effluent: A Critical Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 77, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgacs, E.; Cserháti, T.; Oros, G. Removal of Synthetic Dyes from Wastewaters: A Review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, R.G.; Saratale, G.D.; Chang, J.S.; Govindwar, S.P. Bacterial Decolorization and Degradation of Azo Dyes: A Review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2011, 42, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, H.M.; Touraud, E.; Thomas, O. Aromatic Amines from Azo Dye Reduction: Toxicity, Reactivity and Environmental Impacts. Dye. Pigment. 2004, 63, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Muneer, M.; Haq, A.U.; Akram, N. Photocatalysis: An Effective Tool for Photodegradation of Dyes—A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Poler, J.C. Removal and Degradation of Dyes from Textile Industry Wastewater: Benchmarking Recent Advancements, Toxicity Assessment and Cost Analysis of Treatment Processes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, S.T.G.; Bettanin, F.; Orestes, E.; Homem-de-Mello, P.; Imasato, H.; Viana, R.B.; da Silva, A.B. Photodynamic Efficiency of Xanthene Dyes and Their Phototoxicity against a Carcinoma Cell Line: A Computational and Experimental Study. J. Chem. 2017, 7365263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgar, M.; Gharanjig, K.; Yazdanshenas, M.E.; Farizadeh, K.; Rashidi, A. Photophysical Properties of a Novel Xanthene Dye. Prog. Color Colorants Coat. 2022, 15, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Hussien, S.H.; Hemdan, B.A.; Alzahrani, O.M.; Alswat, A.S.; Alatawi, F.A.; Alenezi, M.A.; Darwish, D.B.E.; Bafhaid, H.S.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Ibrahim, M.F.M.; et al. Microbial Degradation, Spectral Analysis and Toxicological Assessment of MalachiteGreen Dye by Streptomyces exfoliatus. Molecules 2022, 27, 6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilayat, S.; Fazil, P.; Khan, J.A.; Zada, A.; Ali Shah, M.I.; Al-Anazi, A.; Shah, N.S.; Han, C.; Ateeq, M. Degradation of malachite green by UV/H2O2 and UV/H2O2/Fe2+ processes: Kinetics and mechanism. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1467438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aus der Beek, T.; Weber, F.A.; Bergmann, A.; Hickmann, S.; Ebert, I.; Hein, A.; Küster, A. Pharmaceuticals in the Environment—Global Occurrences and Perspectives. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, S.R.; Kay, P.; Brown, L.E. Global Synthesis and Critical Evaluation of Pharmaceutical Data Sets Collected from River Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chefetz, B.; Mualem, T.; Ben-Ari, J. Sorption and Mobility of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Soil Irrigated with reclaimed Wastewater. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziylan, A.; Ince, N.H. The Occurrence and Fate of Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Pharmaceuticals in Sewage and Fresh Water: Treatability by Conventional and Non-Conventional Processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, I.T.; Santos, L. Antibiotics in the Aquatic Environments: A Review of the European Scenario. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 736–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenni, P.; Ancona, P.; Barra Caracciolo, A. Ecological Effects of Antibiotics on Natural Ecosystems: A Review. Microchem. J. 2018, 136, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.C.; Boxall, A.B. Occurrence and Fate of Human Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. Review. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 202, 53–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Dong, Y.; Ni, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wu, X.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Rapid Degradation of Carbamazepine in Wastewater Using Dielectric Barrier Discharge-Assisted Fe3+/Sodium Sulfite Oxidation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, E.M.; Pablos, M.V.; Torija, C.F.; Porcel, M.A.; González-Doncel, M. Uptake of Atenolol, Carbamazepine and Triclosan by Crops Irrigated with Reclaimed Water in a Mediterranean Scenario. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 191, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, E.; Franzellitti, S. Human Pharmaceuticals in the Marine Environment: Focus on Exposure and Biological Effects in Animal Species. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 35, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, A.; Rahman, M.S. Exposure to Metoprolol and Propranolol Mixtures on Biochemical, Immunohistochemical, and Molecular Alterations in the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee. European Union Strategic Approach to Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. COM(2019) 128 Final. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0128 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Boxall, A.B.A.; Rudd, M.A.; Brooks, B.W.; Caldwell, D.J.; Choi, K.; Hickmann, S.; Innes, E.; Ostapyk, K.; Staveley, J.P.; Verslycke, T.; et al. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in the Environment: What Are the Big Questions? Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Spongberg, A.L.; Witter, J.D.; Fang, M. Uptake of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by Soybean Plants from Soils Applied with Biosolids. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 444, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber-Jarlachowicz, P.; Gworek, B.; Kalinowski, R. Removal Efficiency of Pharmaceuticals during the Wastewater Treatment Process: Emission and Environmental Risk Assessment. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0331211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, H.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Z.; Leng, Y.; Liao, M.; Xiong, W. Effects of Three Antibiotics on Nitrogen-Cycling Bacteria in Sediment of Aquaculture Water. Water 2024, 16, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, C.; Hong, Y.; Lee, W.; Chung, H.; Jeong, D.-H.; Kim, H. Distribution and Removal of Pharmaceuticals in Liquid and Solid Phases in the Unit Processes of Sewage Treatment Plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, L. Fundamental Aspects of Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting at Semiconductor Electrodes. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 31, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.O.S.; Goulart, L.A.; Cordeiro-Junior, P.J.M.; Sánchez-Montes, I.; Lanza, M.R.V. Pharmaceutical Contaminants: Ecotoxicological Aspects and Recent Advances in Oxidation Technologies for their Removal in Aqueous Matrices. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalabi, A.M.; Meetani, M.A.; Shabib, A.; Maraqa, M.A. Sorption of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds to Soils: A Review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habimana, E.; Sauvé, S. A Review of Properties, Occurrence, Fate, and Transportation Mechanisms of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Sewage Sludge, Biosolids, Soils, and Dust. Front. Environ. Chem. 2025, 3, 1547596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, S.; Gan, J.; Ernst, F.; Green, R.; Baird, J.; McCullough, M. Leaching of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Turfgrass Soils during Recycled Water Irrigation. J. Environ. Qual. 2012, 41, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Zheng, B.; Zhong, W.; Xu, J.; Nie, W.; Sun, Y.; Guan, Z. Infiltration and Leaching Characteristics of Soils with Different Texture under Irrigation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumlata; Ambade, B.; Kumar, A.; Gautam, S. Sustainable Solutions: Reviewing the Future of Textile Dye Contaminant Removal with Emerging Biological Treatments. Limnol. Rev. 2024, 24, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mastro, F.; Brunetti, G.; Cocozza, C.; Murgolo, S.; Mascolo, G.; Salerno, C.; Ruta, C.; De Mastro, G. Dynamics of Pharmaceuticals in the Soil–Plant System: A Case Study on Mycorrhizal Artichoke. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawn, D.G. Sorption Mechanisms of Chemicals in Soils. Soil Syst. 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.H.; Lima, D.L.D.; Freire, C. Pharmaceutical Contamination in Edible Plants Grown on Soils Amended with Reclaimed Water, Biosolids and Manure: A Review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; Chang, T.F.M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Sone, M.; Hsu, Y.-J. Mechanistic Insights into Photodegradation of Organic Dyes Using Heterostructure Photocatalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, U.; Adelodun, B.; Cabreros, C.; Kumar, P.; Suresh, S.; Dey, A.; Ballesteros, F., Jr.; Bontempi, E. Occurrence, Transformation, Bioaccumulation, Risk and Analysis of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products from wastewater: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 3883–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasket, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Krzmarzick, M.; Gustafson, J.E.; Deng, S. Clay Content Played a Key Role Governing Sorption of Ciprofloxacin in Soil. Front. Soil Sci. 2022, 2, 814924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Essington, M.E.; Chen, X. Polarity Dependence of Transport of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products through Birnessite-Coated Porous Media. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 793587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tang, X.; Thiele-Bruhn, S. Interaction of Pig Manure-Derived DOM with Pharmaceuticals in Soil Systems. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 3859–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allam, K.; Gourai, K.; El Bouari, A.; Belhorma, B.; Bih, L. Adsorption of Methylene Blue on Raw and Activated Clay. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2018, 9, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar]

- González-Naranjo, V.; Boltes, K. Toxicity of ibuprofen and perfluorooctanoic acid for risk assessment of mixtures in aquatic and terrestrial environments. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 11, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Tang, M.; Xu, X. Mechanism of uptake, accumulation, transport, metabolism and phytotoxic effects of pharmaceuticals and personal care products within plants: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Han, H.; Jiang, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, J.; Chen, H. Uptake, Accumulation, Translocation and Transformation of Seneciphylline (Sp) and Seneciphylline-N-Oxide (SpNO) by Camellia sinensis L. Environ. Int. 2023, 188, 108765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Malchi, T.; Carter, L.J.; Li, H.; Gan, J.; Chefetz, B. Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products: From Wastewater Treatment into Agro-Food Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 14083–14090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farsi, R.S.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Busaidi, A.; Choudri, B.S. Translocation of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) into plant tissues: A review. Emerg. Contam. 2017, 3, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Wei, H.; Xie, J.-X.; Wu, Y.-H.; Tang, B.; Zou, Q.; Guo, P.-R.; Chen, Z.-L. Uptake, subcellular distribution, and fate of tetracycline in two wetland plants supplemented with microbial agents: Effect and mechanism. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthanan, S.; Jayasinghe, C.; Biswas, J.K.; Vithanage, M. Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in the Environment: Plant Uptake, Translocation, Bioaccumulation, and Human Health Risks. Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec. 2021, 51, 1221–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matich, E.K.; Chavez Soria, N.G.; Aga, D.S.; Atilla-Gokcumen, G.E. Applications of Metabolomics in Assessing Ecological Effects of Emerging Contaminants and Pollutants on Plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badolati, N.; Masselli, R.; Maisto, M.; Di Minno, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Stornaiuolo, M.; Novellino, E. Genotoxicity Assessment of Three Nutraceuticals Containing Natural Antioxidants Extracted from Agri-Food Waste Biomasses. Foods 2020, 9, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, F.; Masemola, L.; Britz, E.; Ngcobo, N.; Modiba, S.; Cyster, L.; Samuels, I.; Cupido, C.; Raitt, L. Seed Germination and Early Seedling Growth Responses to Drought Stress in Annual Medicago L. and Trifolium L. Forages. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamiu, W.; Oseni, T.O.; Ibrahim, I.A. Phytotoxicity and Health Risk Assessment of Corchorus olitorius L. (Jute) Irrigated with Textile Dyes and Effluents from Itoku Local Dyeing Industry in Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 2025, 29, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Rayhan, M.Y.H.; Chowdhury, M.A.H.; Mohiuddin, K.M.; Chowdhury, M.A.K. Phytotoxic Effect of Synthetic Dye Effluents on Seed Germination and Early Growth of Red Amaranth. Fundam. Appl. Agric. 2018, 3, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicidomini, C.; Palumbo, R.; Moccia, M.; Roviello, G.N. Oxidative Processes and Xenobiotic Metabolism in Plants: Mechanisms of Defense and Potential Therapeutic Implications. J. Xenobiot. 2024, 14, 1541–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higazy, D.; Ahmed, M.N.; Ciofu, O. The Impact of Antioxidant-Ciprofloxacin Combinations on the Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel-Maeso, M.; Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Occurrence, Distribution and Environmental Risk of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PhACs) in Coastal and Ocean Waters from the Gulf of Cadiz (SW Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Tiwari, N.; Tiwari, U. Assessing the Phytotoxicity of Emerging Pollutants on Vegetable Crops Grown with Sewage Effluent. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 989, 179865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Malla, M.A.; Vimal, S.R.; Kumar, A.; Prasad, S.M.; Khan, M.L. Plant-microbiome engineering: Synergistic microbial partners for crop health and sustainability. Plant Growth Regul. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, L.; Kampouris, I.D.; Lüneberg, K.; Heyde, B.J.; Pulami, D.; Glaeser, S.P.; Siebe, C.; Siemens, J.; Smalla, K.; Grohmann, E.; et al. Wastewater-borne pollutants influenced antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in the soil without affecting the bacterial community composition in a changing wastewater irrigation system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negreanu, Y.; Pasternak, Z.; Jurkevitch, E.; Cytryn, E. Impact of Treated Wastewater Irrigation on Antibiotic Resistance in Agricultural Soils and Crops. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 4800–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, T.A. A review of dye biodegradation in textile wastewater, challenges due to wastewater characteristics, and the potential of alkaliphiles. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongthaw, B.; Chauhan, P.K.; Chishty, N.; Kumar, D.; Velmurugan, A.; Singh, A.; Bhtoya, R.; Devi, N.; Nene, A.; Sadeghzade, S.; et al. Aqueous Phase Textile Dye Degradation by Microbes and Nanoparticles: A Review. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 2024, 8845873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, C.; Guerrero, M.; Sánchez, S.; Rodríguez, A.; García, R.M.; Ewbank, A.C.; Gros, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Martínez, I.M.; Guasch, L.; et al. Comparison of Oxytetracycline and Sulfamethazine Effects on Crops and Wild Species: Species-Sensitive Distributions and ECx Values. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 88, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parus, A.; Lisiecka, N.; Klozinski, A.; Zembrzuska, J. Do Microplastics in Soil Influence the Bioavailability of Sulfamethoxazole to Plants? Plants 2025, 14, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikšaitytė, A.; Kacienė, G.; Miškelytė, D.; Januškaitienė, I. Exacerbated Toxicity of Sulfamethoxazole in Growth and Photosynthetic Performance of Hordeum vulgare under Future Climate Scenario. Environ. Res. 2025, 282, 122041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Lu, H.; Lu, S.; Huang, Z. Impacts of Sulfamethoxazole Stress on Vegetable Growth and Rhizosphere Bacteria Composition and Resistance Genes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1303670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, T.; Yao, S.; Yu, Y.; Peng, K.; Jin, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Huang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhu, L. Transformation Process and Phytotoxicity of Sulfamethoxazole and N4-acetyl-sulfamethoxazole in Rice. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, A.K.; Rathi, B.G.; Shukla, S.P.; Kumar, K.; Bharti, V.S. Acute Toxicity of Textile Dye Methylene Blue on Growth and Metabolism of Selected Freshwater Microalgae. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 82, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biczak, R.; Kierasinska, J.; Jamrozik, W.; Pawłowska, B. Response of Maize (Zea mays L.) to Soil Contamination with Diclofenac, Ibuprofen and Ampicillin and Mixtures of These Drugs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zezulka, S.; Kummerová, M.; Oravec, M.; Babula, P. Investigating the Phytotoxic Effects of Binary Mixtures of Diclofenac and Paracetamol on Duckweed–Synergistic or Antagonistic Interaction? Environ. Pollut. 2025, 387, 127295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Duan, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Cai, W.; Zhao, Z. Environmental Impacts and Biological Technologies Toward Sustainable Treatment of Textile Dyeing Wastewater: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacıosmanoglu, G.G.; Arenas, M.; Mejías, C.; Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Adsorption of Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics from Water and Wastewater by Colemanite. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, A.A.; Adeoye, I.O.; Bello, O.S. Adsorption of Dyes Using Different Types of Clay: A Review. Appl. Water. Sci. 2017, 7, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulava, V.M.; Cory, W.C.; Murphey, V.L.; Ulmer, C.Z. Sorption, photodegradation, and chemical transformation of naproxen and ibuprofen in soils and water. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyyappan, J.; Gaddala, B.; Gnanasekaran, R.; Gopinath, M.; Yuvaraj, D.; Kumar, V. Critical Review on Wastewater Treatment using Photo Catalytic Advanced Oxidation Process: Role of Photocatalytic Materials, Reactor Design and Kinetics. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, G.; Iyapparaja, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Drugs and Dyes Using a Machine Learning Approach. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9003–9019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Li, H.; Yu, D.; Zhang, D. g-C3N4-Based Heterojunction for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance: A Review of Fabrications, Applications, and Perspectives. Catalysts 2024, 14, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawary, S.I.S.; Jabbar, H.S.; Hadrawi, S.K.; Alawsi, T.; Abdulelah, F.M.; Altimari, U.S.; Kareem, S.H.; Alawady, A.H.R.; Alsaalamy, A.H.; Mustafa, Y.F. Removal of Malachite Green and Congo Red from Aqueous Media Using Graphite Carbon Nitride (g-c3n4): A Review. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2024, 23, 1607–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammouri, L.; Aboulaich, A.; Capoen, B.; Bouazaoui, M.; Sarakha, M.; Stitou, M.; Mahiou, R. Enhancement under UV–visible and visible light of the ZnO photocatalytic activity for the antibiotic removal from aqueous media using Ce-doped Lu3Al5O12 nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 106, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, X.-X.; Cui, M.-S.; Cui, K.-P.; Dai, Z.-L.; Wang, B.; Weerasooriya, R.; Chen, X. Efficient Degradation of Sulfamethoxazole by Diatomite-Supported Hydroxyl-Modified UIO-66 Photocatalyst after Calcination. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suman, T.-Y.; Kim, S.-Y.; Yeom, D.-H.; Jeon, J. Transformation Products of Emerging Pollutants Explored Using Non-Target Screening: Perspective in the Transformation Pathway and Toxicity Mechanism—A Review. Toxics 2022, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Melián, J.A.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.J.; Ortega-Méndez, A.; Araña, J.; Doña-Rodríguez, J.M.; Pérez-Peña, J. Degradation and Detoxification of 4-Nitrophenol by Advanced Oxidation Technologies and Bench-Scale Constructed Wetlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 105, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, D.A.; Scholz, M. Textile Dye Wastewater Characteristics and Constituents of Synthetic Effluents: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, W.; Sochacka, J.; Wardas, W. Toxicity and Biodegradability of Sulfonamides and Products of Their Photocatalytic Degradation in Aqueous Solutions. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronic, L.; Vlădescu, A.; Enesca, A. Synthesis, Characterisation, Photocatalytic Activity and Aquatic Toxicity Evaluation of TiO2 nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-L.; Chu, W.-L.; Phang, S.-M. Use of Chlorella vulgaris for bioremediation of textile wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 7314–7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezrianjoo, S.; Revanasiddappa, H.D. Eco-Toxicological and Kinetic Evaluation of TiO2 and ZnO Nanophotocatalysts for the Degradation of an Azo Dye (Food Black 1) Under UV Light. Catalysts 2019, 9, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghmandfard, A.; Ghandi, K. A Comprehensive Review of Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4)-based Photocatalysts: Materials, Modifications and Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 4023. [Google Scholar]

- Paiu, M.; Favier, L.; Lutic, D.; Hlihor, R.-M.; Gavrilescu, M. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Tartrazine Using ZnO Nanoparticles: Preliminary Phytotoxicity Investigations on Treated Solutions. Bul. Institutului Politeh. Din Iași Secția Chim. și Ing. Chim. 2024, 70, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, H.; Singh, A.; Shukla, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Chauhan, G. A Review on Photocatalysis Used for Wastewater Treatment. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 25, 100671. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.J.; Pereira, L.; Almeida, A.; Silva, A.M.T. Photocatalytic Degradation of Environmental Contaminants. Catalysts 2025, 15, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.W.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z.; Ong, S.L.; Hu, J.Y. Degradation of Carbamazepine by HF-Free-Synthesized MIL-101(Cr)@Anatase TiO2 Composite under UV-A Irradiation: Degradation Mechanism, Wastewater Matrix Effect, and Degradation Pathway. Water 2022, 14, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Chen, C.; Ji, H.; Che, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhao, J. Unraveling the Photocatalytic Mechanisms on TiO2 Surfaces Using the Oxygen-18 Isotopic Label Technique. Molecules 2014, 19, 16291–16311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.E.; Sahoo, M.K. A Review on Effect of Operational Parameters for the Degradation of Azo Dyes by some Advanced Oxidation Processes. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 11, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberini, A.; Fornaro, T.; García-Florentino, C.; Biczysko, M.; Poblacion, I.; Aramendia, J.; Madariaga, J.M.; Poggiali, G.; Vicente-Retortillo, Á.; Benison, K.C.; et al. Investigating the Stability of Aromatic Carboxylic Acids in Hydrated Magnesium Sulfate under UV Irradiation to Assist Detection of Organics on Mars. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollée, J.E.; Bourgin, M.; von Gunten, U.; McArdell, C.S.; Hollender, J. Non-Target Screening to Trace Ozonation Transformation Products in a Wastewater Treatment Train Including Different Post-Treatments. Water Res. 2018, 142, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, J.; Schymanski, E.L.; Singer, H.P.; Ferguson, L. Nontarget Screening with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry in the Environment: Ready to Go? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 11505–11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Di Lorenzo, T.; Reboleira, A.S.P.S. Environmental Risk of Diclofenac in European Groundwaters and Implications for Environmental Quality Standards. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosek, K.; Zhao, D. Transformation Products of Diclofenac: Formation, Occurrence, and toxicity implication in the Aquatic Environment. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, R.N.; Ceriani, L.; Ippolito, A.; Lettieri, T. Development of the First Watch List Under the Environmental Quality Standards Directive. JCR Technical Report, 2015, European Union, Joint Research Center. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2788/101376 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Hernandez-Zamora, M.; Cruz-Castillo, L.M.; Martinez-Jeronimo, L.; Martinez-Jeronimo, F. Diclofenac Produces Diverse Toxic Effects on Aquatic Organisms of Different Trophic Levels, Including Microalgae, Cladocerans, and Fish. Water 2025, 17, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverett, D.; Merrington, G.; Crane, M.; Ryan, J.; Wilson, I. Environmental Quality Standards for Diclofenac Derived under the European Water Framework Directive: 1. Aquatic Organisms. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trognon, J.; Albasi, C.; Choubert, J.-C. A critical review on the pathways of carbamazepine transformation products in oxidative wastewater treatment processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, S.; Tiwari, A.; Vellanki, B.P. Identification of Emerging Contaminants and their Transformation Products in a Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR)–Based Drinking Water Treatment Plant around River Yamuna in India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Sinha, R.; Roy, D. Toxicological Effects of Malachite Green. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004, 66, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakamercan, E.; Obijianya, C.C.; Jayakrishnan, U.; Aygun, A.; Velluru, S.; Karimi, M.; Terapalli, A.; Simsek, H. A Critical Review of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Reclaimed Wastewater: Implications for Agricultural Irrigation. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Madureira, J.; Justino, G.C.; Cabo Verde, S.; Chmielewska-Śmietanko, D.; Sudlitz, M.; Bulka, S.; Chajduk, E.; Mróz, A.; Wang, S.; et al. Diclofenac Degradation in Aqueous Solution Using Electron Beam Irradiation and Combined with Nanobubbling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, B.I.; Fenner, K. Recent Advances in Environmental Risk Assessment of Transformation Products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3835–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalane, C.M.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Vijaya, J.J.; Jayakumar, C.; Maaza, M.; Jeyaraj, B. Photocatalytic Degradation Effect of Malachite Green and Catalytic Hydrogenation by UV–Illuminated CeO2/CdO Multilayered Nanoplatelet Arrays: Investigation of Antifungal and Antimicrobial Activities. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 169, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusvuran, E.; Gulnaz, O.; Samil, A.; Yildirim, O. Decolorization of Malachite Green, Decolorization Kinetics and Stoichiometry of Ozone-Malachite Green and Removal of Antibacterial Activity with Ozonation Processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshvar, N.; Aber, S.; Seyed Dorraji, M.S.; Khataee, A.R.; Rasoulifard, M.H. Photocatalytic Degradation of the Insecticide Diazinon in the Presence of Prepared Nanocrystalline ZnO Powders Under Irradiation of UV-C Light. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 58, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Lu, X. Land Degradation Affects Soil Microbial Properties, Organic Matter Composition, and Maize Yield. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praus, P.; Gavlova, A.; Hrba, J.; Schmidtova, K.; Bedna, P. Photocatalytic Degradation and Transformation of Pharmaceuticals using Exfoliated Metal-Free g-C3N4. iScience 2025, 28, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellepola, N.; Viera, T.; Patidar, P.L.; Rubasinghege, G. Fate, Transformation and Toxicological Implications of Environmental Diclofenac: Role of Mineralogy and Solar Flux. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihemaiti, M.; Huynh, N.; Mailler, R.; Mèche-Ananit, P.; Rocher, V.; Barhdadi, R.; Moilleron, R.; Le Roux, J. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Screening of Wastewater Effluent for Micropollutants and Their Transformation Products during Disinfection with Performic Acid. ACS EST Water 2022, 2, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, H. Insights into the Pathways, Intermediates, Influence Factors and Toxicological Properties in the Degradation of Tetracycline by TiO2-Based Photocatalysts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimon, V.; Fernandez-Vera, J.R.; Hernandez-Moreno, J.M.; Guedes-Alonso, R.; Estévez, E.; Palacios-Diaz, M.D.P. Soil and Water Management Factors That Affect Plant Uptake of Pharmaceuticals: A Case Study. Water 2022, 14, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, S.; Bielan, Z.; Kubica, P.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. Optimization of Carbamazepine Photodegradation on Defective TiO2-Based Magnetic Photocatalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, Z.H.; Al-Qaim, F.F. Quantification of 10,11-dihydro-10-hydroxy carbamazepine and 10,11-epoxycarbamazepine as the main by-products in the electrochemical degradation of carbamazepine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 62447–62457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andino-Enríquez, M.A.; Fabbri, D.; Vione Calza, P. Photoinduced Transformation Pathways of the Sulfonamide Antibiotic Sulfamethoxazole, Relevant to Sunlit Surface Waters. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 384, 126947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushi Siri, C.N.; Shoukat Ali, R.A.; Latha, M.S.; Betageri, V.S.; Byadagi, K.S. A Reflection of Literature Reports on Synthesis, Spectral Studies, Multilateral Applications of Azo Dyes. Results Chem. 2025, 18, 102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalik, W.F.; Ho, L.N.; Ong, S.A.; Wong, Y.S.; Yusoff, N.A.; Lee, S.L. Revealing the influences of functional groups in azo dyes on the degradation efficiency and power output in solar photocatalytic fuel cell. J. Environ. Health. Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleem, A.; Ullah, M.; Rehman, S.U.; Shah, A.; Farooq, M.; Saeed, T.; Ullah, I.; Li, H. In-Depth Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism of the Extensively Used Dyes Malachite Green, Methylene Blue, Congo Red, and Rhodamine B via Covalent Organic Framework-Based Photocatalysts. Water 2024, 16, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Nian, K.; Long, T. Production of Higher Toxic Intermediates of Organic Pollutants during Chemical Oxidation Processes: A Review. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Estrada, L.A.; Agüera, A.; Hernando, M.D.; Malato, S.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Photodegradation of Malachite Green under Natural Sunlight Irradiation: Kinetic and Toxicity of the Transformation Products. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 2068–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Zhang, P.; Halsall, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.E.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Yao, Z. The Importance of Reactive Oxygen Species on the Aqueous Phototransformation of Sulfonamide Antibiotics: Kinetics, Pathways, and Comparisons with Direct Photolysis. Water Res. 2019, 149, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, P.; Escher, B.I.; Baduel, C.; Virta, M.P.; Lai, F.Y. Antimicrobial Transformation Products in the Aquatic Environment: Global Occurrence, Ecotoxicological Risks, and Potential of Antibiotic Resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9474–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, E.; Masternak, E.; Sapińska, D.; Baran, W. Degradation of the Selected Antibiotic in an Aqueous Solution by the Fenton Process: Kinetics, Products and Ecotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Zeid, S.; Leprince-Wang, Y. Advancements in ZnO-Based Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. ZnO-based photocatalysts for water treatment, including toxicity assessment and removal of pharmaceuticals/pesticides. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvar, J.L.; Santos, J.L.; Martín, J.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Approach to the Dynamic of Carbamazepine and Its Main Metabolites in Soil Contamination through the Reuse of Wastewater and Sewage Sludge. Molecules 2020, 25, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Ikram, M.; Zheng, B. ROS Regulation and Antioxidant Responses in Plants Under Air Pollution: Molecular Signaling, Metabolic Adaptation, and Biotechnological Solutions. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahabuddin, L. Development of Cobalt Nickel Doped TiO2 Nanowires as Efficient Photocatalysts for Removal of Tartrazine Dyes. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2024, 6, 3064–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodešová, R.; Švecová, H.; Klement, A.; Fer, M.; Nikodem, A.; Fedorova, G.; Rieznyk, O.; Kočárek, M.; Sadchenko, A.; Chroňáková, A.; et al. Contamination of Water, Soil, and Plants by Micropollutants from Reclaimed Wastewater and Sludge from a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.C.; Simionato, J.I.; de Cinque Almeida, V.; Palácio, S.M.; Rossi, F.L.; Schneider, M.V.; de Souza, N.E. Evolutive Follow-up of the Photocatalytic Degradation of Real Textile Effluents in TiO2 and TiO2/H2O2 Systems and Their Toxic Effects on Lactuca sativa Seedlings. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2009, 20, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L.M.; de Souza, G.M.; Fernandes, S.A.; Rodrigues Rocha, E.M. Evaluation of the acute phytotoxicity of photo-treated textile effluents using Lactuca sativa seeds. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Ambient. 2024, 49, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowiak, R.; Musial, J.; Bakun, P.; Spychała, M.; Czarczynska-Goslinska, B.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Koczorowski, T.; Sobotta, Ł.; Stanisz, B.; Goslinski, T. Titanium Dioxide-Based Photocatalysts for Degradation of Emerging Contaminants including Pharmaceutical Pollutants. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, A.; Coria, D.; Alvarez, J.; Muñoz, V. Study of La Candelaria Streams Water Photocatalysis: Optimization and Biotoxicity Evaluation by Lactuca sativa Bioassay. Res. Square 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliste, M.; Hernández, V.; El Aatik, A.; Pérez-Lucas, G.; Fenoll, J.; Navarro, S. Coupled Bio-Solar Photocatalytic Treatment for Reclamation of Water Polluted with Pharmaceuticals—Ecotoxicity Evolution during Treatment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 287, 117291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.; Cabrera, E.V.; Stahl, U.; Correa-Abril, J. Kinetic and Equilibrium Analysis of Tartrazine Photocatalytic Degradation Using Iron-Doped Biochar from Theobroma cacao L. Husk via Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis. Chem. Proc. 2024, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jari, Y.; Najid, N.; Necibi, M.K.; Gourich, B.; Vial, C.; Elhalil, A.; Kaur, P.; Mohdeb, I.; Park, Y.; Hwang, Y.; et al. A comprehensive review on TiO2-based heterogeneous photocatalytic technologies for emerging pollutants removal from water and wastewater: From engineering aspects to modeling approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.K. Recent Advances in Removal of Pharmaceutical Pollutants in Wastewater using Metal Oxides and Carbonaceous Materials as Photocatalysts: A Review. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2024, 1, 340–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Qu, J. Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Contaminants. Toxics 2025, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.; Ojha, A.; Kansal, S.K.; Gupta, N.K.; Swart, H.C.; Cho, J.; Kuznetsov, A.Y.; Sun, S.; Prakash, J. Advances in powder nano-photocatalysts as pollutant removal and as emerging contaminants in water: Analysis of pros and cons on health and environment. Adv. Powder Mater. 2024, 3, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhajeb, O.; Hammami, R.; Megriche, A.; Özacar, M. Boosting Photocatalytic Efficiency of MAPbCl3/TiO2/SiO2 Heterostructure with Mn Doping for Tartrazine Degradation. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2026, 323, 118732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.; Talami, B.; Almansba, A.; Bonnet, P.; Caperaa, C.; Dalhatou, S.; Kane, A.; Zeghioud, H. Photocatalytic Degradation of Tartrazine and Naphthol Blue Black Binary Mixture with the TiO2 Nanosphere under Visible Light: Box-Behnken Experimental Design Optimization and Salt Effect. ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzzeka, C.; Goldoni, J.; Lenzi, G.G.; Bagatini, M.D.; Colpini, L.M.S. Photocatalytic Action of Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles to Emerging Pollutants Degradation: A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 8, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.D.; Ammar, S.H.; Rashed, M.K.; Jabbar, Z.H.; Hadi, H.J. Boosting visible-light-promoted photodegradation of norfloxacin by S-doped g-C3_33N4_44 grafted by NiS as robust photocatalytic heterojunctions. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1312, 138611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde-Sanz, L.; Gawlik, B.M. Minimum Quality Requirements for Water Reuse in Agricultural Irrigation and Aquifer Recharge; Towards a Legal Instrument on Water Reuse at EU Level; EUR 28962 EN; European Commission, Joint Research Center, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017.

- European Union (EU). Regulation (EU) 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Minimum Requirements for Water Reuse; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- WHO. Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater in Agriculture; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241546859 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- USEPA. 2012 Guidelines for Water Reuse; EPA/600/R-12/618; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/waterreuse/guidelines-water-reuse (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- ISO 16075; Guidelines for Treated Wastewater Use for Irrigation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020–2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/73482.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ayers, R.S.; Westcot, D.W. Water Quality for Agriculture; FAO Irrigation and Drainage, Paper 29 Rev. 1; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1985; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/t0234e/t0234e00.htm (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- European Union (EU). Directive 2008/105/EC on Environmental Quality Standards in the Field of Water Policy (consolidated text, as amended by Directive 2013/39/EU); Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2008/2013.

- IEEP. Manual of European Environmental Policy—Disposal of Sewage Sludge; Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK; Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://ieep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/6.10_Disposal_of_sewage_sludge_-_final.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Stando, K.; Wilk, J.; Jakóbik-Kolon, A.; Felis, E.; Bajkacz, S. Application of UHPLC-MS/MS to Monitor Sulfonamides and Their Transformation Products in Soils in Silesia, Poland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 112922–112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola, M.; Kougias, P.G.; Statiris, E.; Papadopoulou, P.; Malamis, S.; Monokrousos, N. Short-Term Effect of Reclaimed Water Irrigation on Soil Health, Plant Growth and the Composition of Soil Microbial Communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, M.S.; Abdalla, S.; Abdelrahman, A.A.; Amin, I.A.; Ramadan, M.; Salah, M. Irrigation Water Quality Shapes Soil Microbiomes: A 16S rRNA-Based Biogeographic Study in Arid Ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho Mendes, I.; Cerrados, E. Standard Operating Procedure for Soil Enzyme Activities. β-Glucosidases, Arylsulfatase, N-Acetyl-β-Glucosaminidase, Dehydrogenase, Phosphomonoesterases; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/c2eea5c9-65db-42bd-9eca-0579507dd694/content (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Mravcová, L.; Syslová, K.; Vávrová, M.; Koutník, I.; Rehůřková, I.; Kalina, J.; Golovko, O.; Škulcová, A.; Horký, P.; Křesinová, Z.; et al. Optimization and Validation of Multiresidual Extraction for the Determination of Pharmaceuticals in Soil, Lettuce and Earthworms by LC-MS/MS. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 33120–33140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mravcová, L.; Jašek, V.; Hamplová, M.; Navrkalová, J.; Amrichová, A.; Zlámalová Gargosšová, H.; Fucčík, J. Assessing Lettuce Exposure to a Multipharmaceutical Mixture under Hydroponic Conditions: Findings through LC-ESI-TQ Analysis and Ecotoxicological Assessments. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 49707−49718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMA. Guideline on the Environmental Risk Assessment of Medicinal Products for Human Use (Revision 1); European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-environmental-risk-assessment-medicinal-products-human-use-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ryu, H.-D.; Kim, J.-H.; Han, H.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, Y.S. Ecological Risk Assessment and Sustainable Management of Pollutants in Hydroponic Wastewater from Plant Factories. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinken, J.F.; Pasmooij, A.M.G.; Ederveen, A.G.H.; Hoekman, J.; Bloem, L.T. Environmental risk assessment in the EU regulation of medicines for human use: An analysis of stakeholder perspectives on its current and future role. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finckh, S.; Beckers, L.-M.; Busch, W.; Carmona, E.; Dulio, V.; Kramer, L.; Krauss, M.; Posthuma, L.; Schulze, T.; Slootweg, T.; et al. A Risk Based Assessment Approach for Chemical Mixtures from Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents. Environ. Int. 2022, 164, 107234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faunce, K.E.; Barber, L.B.; Keefe, S.H.; Jasmann, J.R.; Rapp, J.L. Wastewater reuse and predicted ecological risk posed by contaminant mixtures in Potomac River watershed streams. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2023, 59, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszar, S.A.; Vitale, C.M.; Vamshi, R.; Carmona, E.; Dulio, V.; Kramer, L.; Krauss, M.; Posthuma, L.; Schulze, T.; Slootweg, T.; et al. Spatially Referenced Environmental Exposure Model for Down-the-Drain Substance Emissions across European Rivers for Aquatic Safety Assessments. Integr. Environ. Asses. Manag. 2025, vjaf119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Trias, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Verlicchi, P.; Buttiglieri, G. Selection of Pharmaceuticals of Concern in Reclaimed Water for Crop Irrigation in the Mediterranean Area. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, K.; Sleight, H.; Ashfield, N.; Boxall, A.B.A. Are Pharmaceutical Residues in Crops a Threat to Human Health? J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2024, 87, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gao, T.; Gao, Z.; Lai, C.W.; Xiang, P.; Yang, F. Global Distribution, Ecotoxicity, and Treatment Technologies of Emerging Contaminants in Aquatic Environments: A Recent Five-Year Review. Toxics 2025, 13, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.; Mecha, A.C.; Samuel, H.M.; Suliman, Z.A. Recent Trends in the Application of Photocatalytic Membranes in Removal of Emerging Organic Contaminants in Wastewater. Processes 2025, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyengabe, A.; Banda, M.F.; Augustyn, W. Predicting plant uptake of potential contaminants of emerging concerns using machine learning models (2018–2025): A global review. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, W.; Xi, Y.; Li, X. Comprehensive Review of Emerging Contaminants: Detection Technologies, Environmental Impact, and Management Strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denora, M.; Mehmeti, A.; Candido, V.; Brunetti, G.; De Mastro, F.; Murgolo, S.; De Ceglie, C.; Gatta, G.; Giuliani, M.M.; Fiorentino, C.; et al. Fate of Emerging Contaminants in the Soil-Plant System: A Study on Durum Wheat Irrigated with Treated Municipal Wastewater. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1448016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, N.; Chen, T.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H. Accumulation and Subcellular Distribution Patterns of Carbamazepine in Hydroponic Vegetables. Biology 2025, 14, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, E.R.; Coldren, C.; Williams, C.; Simpson, C. Uptake, Partitioning, and Accumulation of High and Low Rates of Carbamazepine in Hydroponically Grown Lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. capitata). Plants 2025, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejías, C.; Arenas, M.; Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Multiclass Analysis for the Determination of Pharmaceuticals and Their Main Metabolites in Leafy and Root Vegetables. Molecules 2024, 29, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, O.Z.; Olawade, D.B. Recent Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals in Freshwater, Emerging Treatment Technologies, and Future Considerations: A Review. Chemosphere 2025, 374, 144153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mastro, F.; Traversa, A.; Cocozza, C.; Cacace, C.; Provenzano, M.R.; Vona, D.; Sannino, F.; Brunetti, G. Fate of Carbamazepine and Its Metabolites in a Soil–Aromatic Plant System. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, F.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Fu, Y.; Xiang, L.; Sheng, H.; Li, Z.; Hashsham, S.A.; Jiang, X.; Tiedje, J.M. Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes from Soil to Rice in Paddy Field. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 108956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Sun, A.; Yuan, R.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B. The Influence Mechanism of Dissolved Organic Matter on the Photocatalytic Oxidation of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products. Molecules 2025, 30, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Pollutant/Matrix | Treatment Process | Bioassay and Endpoint | Toxicity Before Treatment (EC50/LC50) | Toxicity After Treatment (EC50/LC50) | Detoxification Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Textile secondary effluent (dyes + organics) | TiO2 photocatalysis (suspended catalyst) | Daphnia similis, 48 h immobilization (EC50, % effluent) | 70.7% (raw effluent) | 95.0% (after TiO2 treatment) | Toxicity decreases (higher EC50) |

| Textile secondary effluent | HT/Fe/TiO2 photocatalyst | Daphnia similis, 48 h immobilization (EC50, % effluent) | 70.7% | 78.6% | Moderate toxicity decrease |

| Pharmaceutical wastewater | N-Cu-TiO2/CQD photocatalysis (visible light) | Daphnia magna, acute toxicity (EC50, % effluent) | 62.5% | ≈150% (after photocatalysis) | Strong toxicity decrease |

| PAHs mixture in water | GO–TiO2–Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 photocatalysis | Daphnia magna, acute toxicity (EC50, ng/mL) | 342.56 ng/mL | 631.05 ng/mL | Toxicity decreases |

| Brilliant Blue FCF dye | Ozonation (200 mg O3/L; 50% dilution) | Daphnia magna, 48 h immobilization (EC50, mg/L) | EC50 > 100 mg/L | 4.8 mg/L | Toxicity increases |

| Diclofenac (model solution) | Ultrasonic AOP (sonication, 240 s) | Daphnia magna, acute toxicity (EC50, mg/L) | 103.4 mg/L | 133.7 mg/L | Toxicity decreases |

| Leather wastewater | ZnO photocatalysis | Artemia salina, 24 h LC50 (% effluent) | 14.9% | 56.82% | Toxicity decreases |

| Jeans laundry textile effluent | TiO2 P25 photocatalysis | Artemia salina, LC50 (% effluent) | 27.59% | 90.86% | Toxicity decreases |

| Compound/Class | Representative Use | Log Kₒw | pKa | Water Solubility (mg L−1) | Main Factors Influencing Fate in Soil–Plant Systems | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diclofenac (NSAID) | Analgesic, anti-inflammatory | 4.51 | 4.0 | 2.4 | Moderately hydrophobic; ionized at neutral pH; sorbs to organic matter; limited mobility; partial plant uptake | [31,37,39,80] |

| Carbamazepine (antiepileptic) | Psychotropic drug | 2.45 | 13.9 | 17.7 | Neutral at environmental pH; persistent; weak sorption; readily taken up and translocated in plants | [40,41,81,82] |

| Sulfamethoxazole (antibiotic) | Antimicrobial | 0.9 | 5.6 | 610 | Ionizable; mobile in soils; limited sorption; affects microbial activity and nitrogen cycling | [19,20,42,83] |

| Ciprofloxacin (antibiotic) | Fluoroquinolone | 1.3 | 6.1 | 30 | Strong sorption to clays; cation exchange interactions; restricted plant uptake; accumulates in roots | [31,37,43,84] |

| Ibuprofen (NSAID) | Analgesic | 3.97 | 4.9 | 21 | Weak acid; moderately hydrophobic; sorption to organic matter; partial biodegradation | [1,31,37] |

| Atenolol (β-blocker) | Cardiovascular agent | 0.16 | 9.6 | 13,000 | Hydrophilic; limited sorption; leaches easily; potential foliar absorption from irrigation sprays | [38,40,79,81] |

| Tartrazine (azo dye) | Food/textile colorant | 2.5 | 10.1 | 1200 | Anionic; mobile in soil solution; may inhibit root growth and photosynthetic enzymes | [8] |

| Methylene Blue (cationic dye) | Textile dye, disinfectant | 0.6 | — | 43,600 | High solubility; electrostatic adsorption on clays; strong root surface binding; photosensitizing activity | [8,10] |

| Reactive Black 5 (azo dye) | Textile dye | 1.6 | 7.1 | 200 | Hydrophilic; resistant to biodegradation; persistent in soil–water interface; limited plant uptake | [10] |

| Soil Property | Condition/Range | Compound(s) | Reported Metric (Units) | Key Effect/Finding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay content & CEC | 20 agricultural soils; variable clay, CEC (acidic conditions) | Ciprofloxacin | Sorption capacity: 8–141 g kg−1; Kd: 23–200 mL kg−1; Koc: 54–2146 mL g−1 OC; correlations: r(clay) = 0.92 *, r(CEC) = 0.64 *; pH effect r < 0.25 | Sorption (and reduced mobility) increases with clay and CEC; pH had little effect in this set. | [57,97] |

| Soil organic carbon (SOM, OC) & speciation | Cross-study synthesis (137 papers; 106 PACs; batch & column) | Class comparison | Average Koc spans 0.0915 mL g−1 (anionic sulfonamides) to 84,725.5 mL g−1 (zwitterionic norfloxacin); sorption with OC; zwitterion > cation > neutral > anion | Higher OC and positive speciation (zwitterion/cation) strongly increase sorption (lower bioavailability/mobility). | [47,87] |

| Texture (coarse fine) & sorption variability | Five soils with contrasting texture/OC | Carbamazepine | Kd (measured): 1.08–14.88 L kg−1; literature 0.43–37 L kg−1 | Low–moderate sorption; more mobile in sandy/low-OC soils; texture and OC drive variability. | [58,98] |

| Texture/OC | Five soils (as above) | Ibuprofen | Kd (measured): 0.29–20.32 L kg−1; literature typically 0.15–3.71 L kg−1 | Sorption ranges widely with soil; higher OC/finer texture increases retention (reduces mobility). | [58,98] |

| pH/charge interactions & low sorption acids | Multi-soil comparison | Sulfameter (sulfonamide) | Literature Kd: 0.09–0.17 L kg−1 | Weak sorption for anionic sulfonamides, higher mobility/leaching risk in many soils. | [58,98] |

| CEC & OC (cultivation effects) | Same 20-soil dataset; cultivated vs. uncultivated | Ciprofloxacin | In cultivated soils: r(OC, capacity) = 0.96 *; r(OC, Kd) = 0.72 * | Cultivation altered SOM quality; OC correlated strongly with sorption only in cultivated soils. | [57,97] |

| Dissolved organic matter (DOM) competition | Manure-DOM 0–140 mg C L−1 | Atenolol (also sulfadiazine, caffeine) | DOM up to 140 mg C L−1 decreased soil sorption of atenolol (mobilizing effect) | DOM competes/complexes, increasing dissolved fraction and potential mobility. | [59,99] |

| Cationic dye–clay electrostatics (CEC proxy) | Raw vs. activated clay | Methylene blue (cationic dye) | Langmuir qₘ: 30–50.2 mg g−1; higher on activated clay | Strong electrostatic adsorption to clay surfaces; higher capacity with more reactive clay (increased CEC/area). | [60,100] |

| Texture–hydraulics (infiltration & leaching potential) | Sandy vs. loamy vs. clayey soils (irrigation scenarios) | General (PACs/dyes) | Higher infiltration in coarse textures | Coarse-textured soils favor percolation & leaching of weakly sorbing, soluble compounds (increased bioavailability below root zone). | [50,90] |

| Recycled-water irrigation (field lysimeters) | Turfgrass soils under TWW irrigation | Mixed PPCPs | Detection in leachate below root zone | Weakly sorbing PPCPs can leach under irrigation; texture/irrigation intensity modulate fluxes. | [49,89] |

| Topic | Matrix/ Species | Compound(s) | Exposure Design | Key Numeric Result(s)/Finding | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration–effect patterns and thresholds | Crops & wild species (multi-species meta/SSD) | Oxytetracycline (OTC) | Multiple lab datasets aggregated; plant growth endpoints | EC10 = 0.39–26.64 mg L−1 (crops), 0.18–64.34 mg L−1 (wild); EC50 = 18.0–846.78 mg L−1 (crops), 46.02–2611.49 mg L−1 (wild). | [82,122] |

| Sorption controls on ECx (context) | Review/soils | Multiple classes | Synthesis of 137 studies (batch/column) | Higher sorption to clay/OM and CEC sites predicts higher ECx in shoots; weakly sorbing compounds show lower ECx in sandy/low-OC soils. | [47,87] |

| Hormesis/low-dose stimulation | Soil–plant (pot): sorghum | Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) ± 1% microplastics | 0–50 mg kg−1 soil; germination and biomass endpoints | ≤5 mg kg−1: stimulation; ≥25 mg kg−1: inhibition; 1% MPs reduced SMX toxicity by lowering bioavailability. | [83,123] |

| Hormesis (broader synthesis) | Review/plants | SMX and related antibiotics | Narrative synthesis | Low-dose stimulation, high-dose inhibition (hormetic biphasic response) across plant endpoints. | [84,124] |

| Time-dependent toxicity (longer exposure) | Vegetables (basil, cilantro, spinach) | SMX | Multi-week exposure vs. short-term; growth + rhizosphere | Longer exposure increased impairment and ARG abundances versus short exposure (time-dependent toxicity). | [85,125] |

| Transformation products matter | Rice | SMX → N4-acetyl-SMX | Uptake/translocation and toxicity study | N4-acetyl-SMX formed in situ and contributed to toxicity; transformation shifts dose–response vs. nominal SMX. | [86,126] |

| Dyes: acute vs. prolonged effects | Microalgae (primary producers) | Methylene blue (MB) | Acute lab tests | Concentration-dependent inhibition of growth and metabolism; strong acute effect. | [87,127] |

| Mixtures (plant) | Maize (soil) | Diclofenac, Ibuprofen, Ampicillin; single, binary, ternary | 0–1000 mg kg−1 in soil; 14 days | At 1000 mg kg−1, Fv/F0 decreased ≈ 10–12%; mixtures produced similar or additive inhibition patterns. | [88,128] |

| Mixtures (aquatic plant model) | Duckweed (Lemna minor) | Diclofenac + Paracetamol | 0.2–20 mg L−1 each, 7-day exposure | Mixture interaction ambiguous; DCF toxicity dominated; accumulation similar between single and binary exposures. | [89,129] |

| Modeling guidance | Review/multi-class | Pharmaceuticals and dyes | ECx modeling and risk comparison guidance | 4-parameter log-logistic or Weibull for standard endpoints; Brain–Cousens for hormesis; use TWA or BMD when TPs accumulate. | [65,85,86,105,125,126] |

| Parent Compound | Photocatalyst/Light Source | Identified Transformation Products (TPs) | Extent of Degradation/Mineralization | Key Findings and Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|