Plant Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses: Mechanisms, Defense Strategies, and Nanoparticle-Assisted Remediation

Abstract

1. Introduction

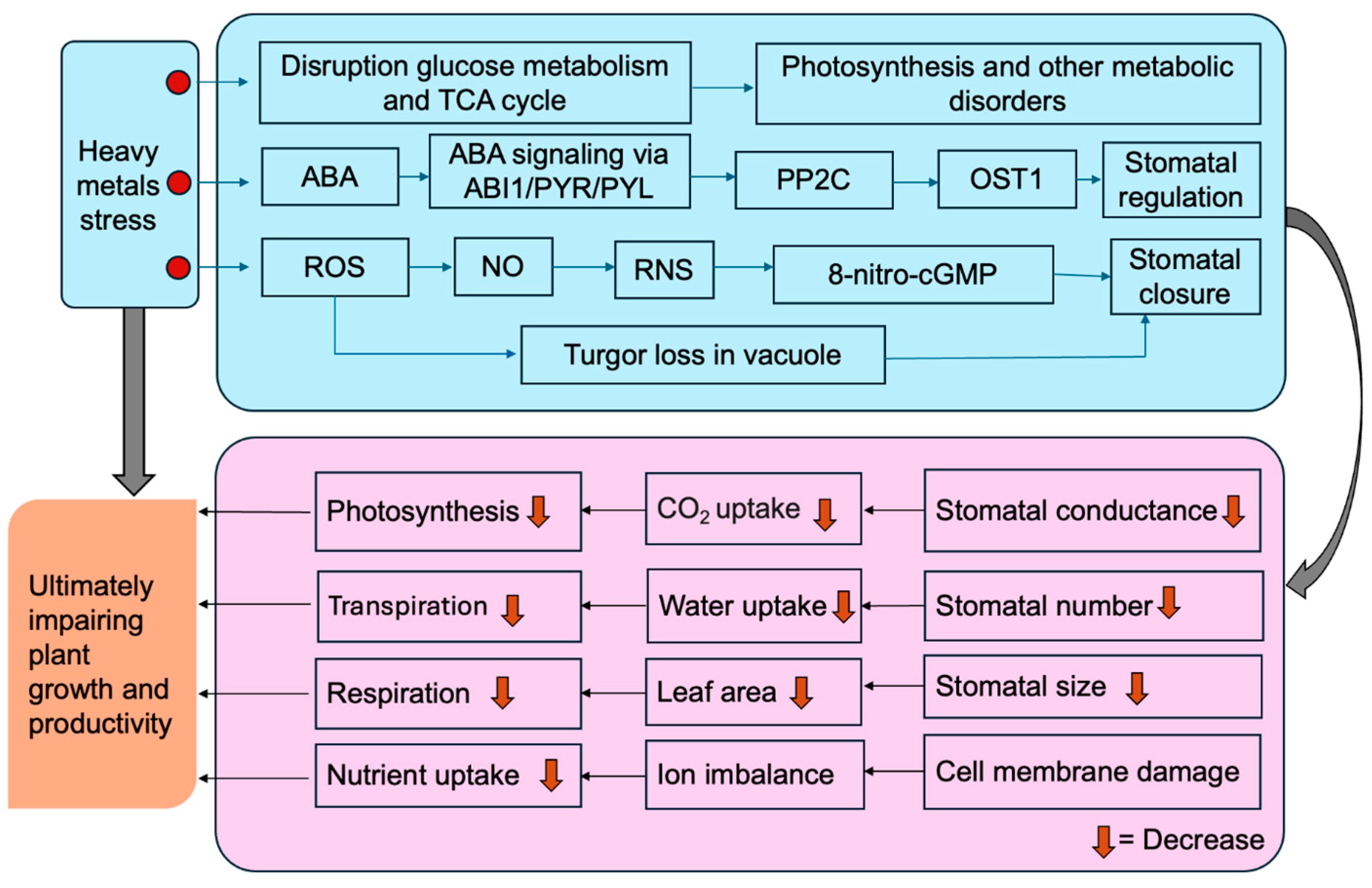

2. Roles of Heavy Metals in Plants

3. Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses

4. Disruption of Cell Membrane Integrity, Oxidative Homeostasis, and Enzymatic Activities Under Heavy Metal Stresses

5. Plants’ Resistance Mechanisms to Heavy Metal Stresses

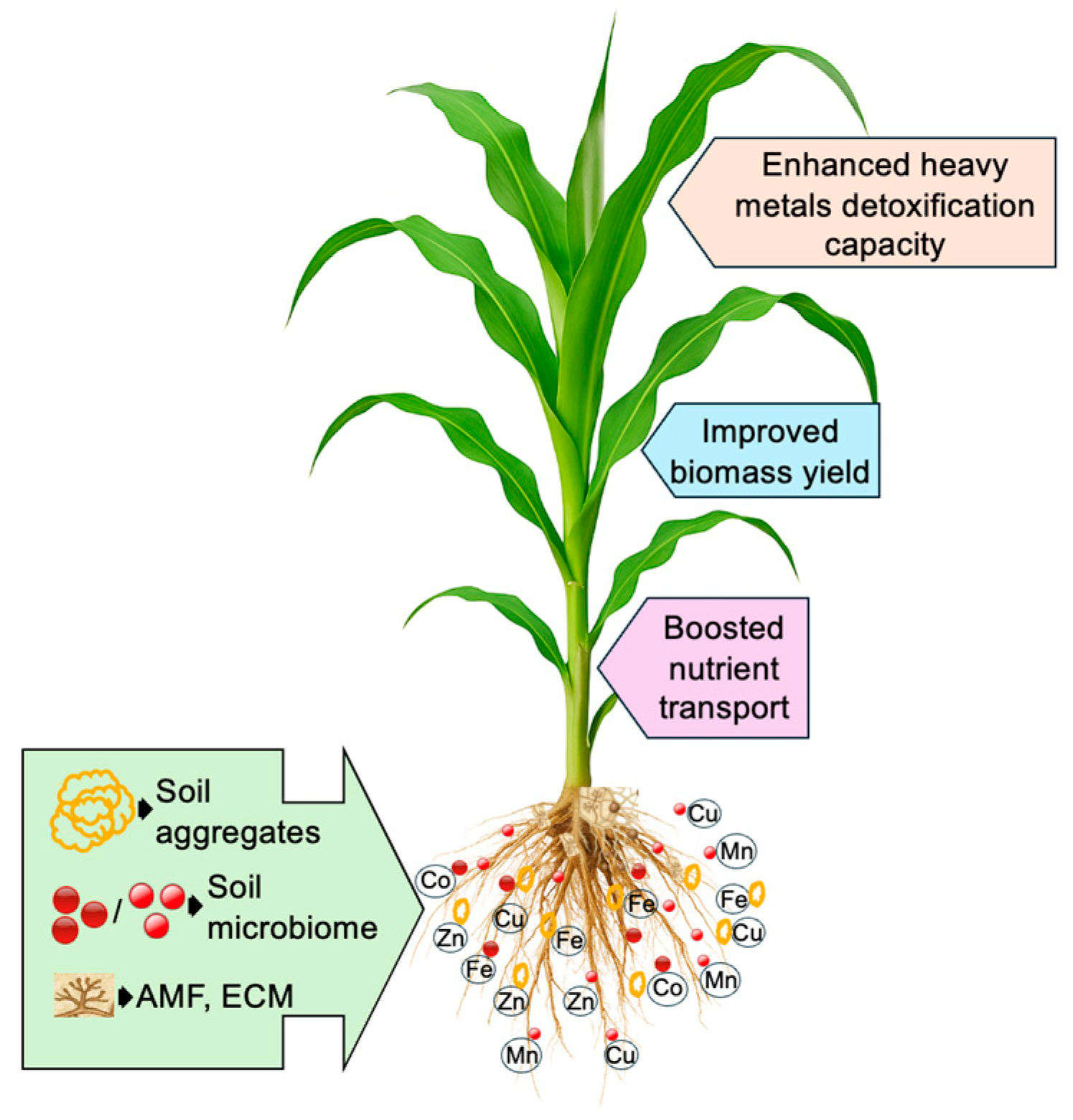

5.1. Immobilization by Mycorrhizal Associations

5.2. Root-Mediated Mechanisms and Phytochelatin-Driven Detoxification Under Heavy Metal Stresses

- i.

- Plant’s cell wall, rich in pectin and lignin, can adsorb HMs through ion exchange, thereby reducing metal mobility and entry into cells [152].

- ii.

- Specific membrane transporters and channel proteins regulate HM uptake. Under HM stress, plants often downregulate these transporters to reduce metal influx [118].

- iii.

- Chelation is a widespread detoxification mechanism involving intracellular ligands such as PCs, MTs, organic acids (e.g., citric, malic, oxalic acids), and amino acids (e.g., histidine, nicotianamine), which bind free metal ions and prevent them from interfering with vital metabolic processes [153].

- iv.

- The tonoplast (vacuolar membrane) minimizes HM movement back into the cytoplasm via active permeability mechanisms, serving as a dynamic barrier against metal recirculation [147].

- v.

5.3. Antioxidant Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses

5.4. Regulation of Signaling Pathways and Gene Expression in Plants Under Heavy Metal Stresses

6. Nanoparticle-Mediated Alleviation of Heavy Metal Stresses in Plants

7. Nanoparticle-Assisted Bioremediation Against Heavy Metal Stresses

8. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

- i.

- Deciphering complex plant–microbiome–NPs interactions to optimize rhizosphere processes for HM detoxification.

- ii.

- Applying synthetic biology and CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing to enhance key regulatory genes, transcription factors, and transporters for improved HM stress tolerance.

- iii.

- Integrating multi-omics tools to unravel the regulatory networks and crosstalk between physiological, biochemical, and molecular pathways involved in HM stress tolerance.

- iv.

- Evaluating the long-term ecological risks and field performance of NPs, with emphasis on safe design, environmental fate, and regulatory frameworks.

- v.

- Developing scalable, field-applicable nanoparticle-assisted phytoremediation protocols that combine engineered plants, beneficial microbes, and smart nanomaterials for site-specific remediation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, A.J.M. Accumulators and excluders-strategies in the response of plants to heavy metals. J. Plant Nutr. 1981, 3, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanikenne, M.; Nouet, C. Metal hyperaccumulation and hypertolerance: A model for plant evolutionary genomics. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.S.; Yu, S.; Zhu, Y.G.; Li, X.D. Trace metal contamination in urban soils of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 421, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Guo, W.; Dang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Wu, F.; Feng, C.; Zhao, X.; Meng, W.; Xing, B.; Giesy, J.P. Refocusing on nonpriority toxic metals in the aquatic environment in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13960–13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakov, A.E.; Galunin, E.V.; Burakova, I.V.; Kucherova, A.E.; Agarwal, S.; Tkachev, A.G.; Gupta, V.K. Adsorption of heavy metals on conventional and nanostructured materials for wastewater treatment purposes: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 148, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kapoor, D.; Khasnabis, S.; Singh, J.; Ramamurthy, P.C. Mechanism and kinetics of adsorption and removal of heavy metals from wastewater using nanomaterials. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2351–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, R.; Iqbal, N.; Masood, A.; Khan, M.I.R.; Syeed, S.; Khan, N.A. Cadmium toxicity in plants and role of mineral nutrients in its alleviation. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 1476–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Zia, M.A.; Kamran, M.; Shabaan, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Ahmad, M.; Maqsood, M.F. Nanoremediation for heavy metal contamination: A review. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 4, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Ilyas, N.; Bibi, F.; Shabir, S.; Mehmood, S.; Akhtar, N.; Eldin, S.M. Nanoremediation approaches for the mitigation of heavy metal contamination in vegetables: An overview. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20230156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małkowski, E.; Sitko, K.; Zieleźnik-Rusinowska, P.; Gieroń, Ż.; Szopiński, M. Heavy metal toxicity: Physiological implications of metal toxicity in plants. In Plant Metallomics and Functional Omics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 253–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghori, N.; Ghori, T.; Hayat, M.Q.; Imadi, S.R.; Gul, A.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Heavy metal stress and responses in plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1807–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, U. Metal hyperaccumulation in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, N.; Hermans, C.; Schat, H. Mechanisms to cope with arsenic or cadmium excess in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schat, H.; Llugany, M.; Bernhard, R. Metal-specific patterns of tolerance, uptake, and transport of heavy metals in hyperaccumulating and nonhyperaccumulating metallophytes. In Phytoremediation of Contaminated Soil and Water, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Rehman, S.; Khan, A.Z.; Khan, M.A.; Shah, M.T. Soil and vegetables enrichment with heavy metals from geological sources in Gilgit, northern Pakistan. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 1820–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Pinelli, E.; Pourrut, B.; Silvestre, J.; Dumat, C. Lead-induced genotoxicity to Vicia faba L. roots in relation with metal cell uptake and initial speciation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 74, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, B.; Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Chromium immobilization by extraradical mycelium of arbuscular mycorrhiza contributes to plant chromium tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 122, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, C.; Wahsha, M.; Fontana, S.; Maleci, L. Effects of heavy metals on morphological characteristics of Taraxacum officinale Web growing on mine soils in NE Italy. J. Geochem. Explor. 2012, 123, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.A.; Qamar, Z.; Waqas, M. The uptake and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by food plants, their effects on plants nutrients, and associated health risk: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 13772–13799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellem, J.J.; Baijnath, H.; Odhav, B. Translocation and accumulation of Cr, Hg, As, Pb, Cu and Ni by Amaranthus dubius (Amaranthaceae) from contaminated sites. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2009, 44, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Kariman, K. Physiological and antioxidative responses of medicinal plants exposed to heavy metals stress. Plant Gene 2017, 11, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, A. Phenolic compounds and their antioxidant activity in plants growing under heavy metal stress. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2006, 15, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Delmar, J.A.; Su, C.C.; Yu, E.W. Heavy metal transport by the CusCFBA efflux system. Protein Sci. 2015, 24, 1720–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalaria, R.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuča, K.; Torequl Islam, M.; Verma, R. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as potential agents in ameliorating heavy metal stress in plants. Agronomy 2020, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Vibhandik, R.; Agrahari, R.; Daverey, A.; Rani, R. Role of root exudates on the soil microbial diversity and biogeochemistry of heavy metals. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 2673–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Oliveira, R.S.; Freitas, H.; Luo, Y. Bioaugmentation with endophytic bacterium E6S homologous to Achromobacter piechaudii enhances metal Rhizoaccumulation in host Sedum plumbizincicola. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusaravanan, S.; Sivarajasekar, N.; Vivek, J.S.; Paramasivan, T.; Naushad, M.; Prakashmaran, J.; Gayathri, V.; Al-Duaij, O.K. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Mechanisms, methods and enhancements. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 1339–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Abbas, N.; Arshad, F.; Akram, M.; Khan, Z.I.; Ahmad, K.; Mansha, M.; Mirzaei, F. Effects of diverse doses of lead (Pb) on different growth attributes of Zea mays L. Agric. Sci. 2013, 4, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, R.; Sharma, R. Effect of heavy metals: An overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 51, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djingova, R.; Kuleff, I. Instrumental techniques for trace analysis. In Trace Metals in the Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 4, pp. 137–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, I.; Ensley, B.D. Phytoremediation of Toxic Metals: Using Plants to Clean up the Environment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Available online: http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA45677643 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Jadia, C.D.; Fulekar, M.H. Phytoremediation of heavy metals: Recent techniques. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, M.K.; Majumdar, A. Heavy metals’ stress responses in field crops. In Response of Field Crops to Abiotic Stress; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E. Plant Physiology, 3rd ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.A.; Detterbeck, A.; Clemens, S.; Dietz, K.J. Silicon-induced reversibility of cadmium toxicity in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 3573–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruyter-Hooley, M.; Larsson, A.C.; Johnson, B.B.; Antzutkin, O.N.; Angove, M.J. The effect of inositol hexaphosphate on cadmium sorption to gibbsite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 474, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, R.; Larios, R.; Gómez-Pinilla, I.; Gómez-Mancebo, B.; López-Andrés, S.; Loredo, J.; Ordóñez, A.; Rucandio, I. Mercury accumulation and speciation in plants and soils from abandoned cinnabar mines. Geoderma 2015, 253–254, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, R.L.; Lockwood, P.E.; Tseng, W.Y.; Edwards, K.; Shaw, M.; Caughman, G.B.; Lewis, J.B.; Wataha, J.C. Mercury (II) alters mitochondrial activity of monocytes at sublethal doses via oxidative stress mechanisms. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2005, 75, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeid, I. Responses of Phaseolus vulgaris to chromium and cobalt treatments. Biol. Plant. 2001, 44, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.; Tiwari, M.; Dutta, P.; Singh, P.; Chawda, K.; Kumari, M.; Chakrabarty, D. Chromium stress in plants: Toxicity, tolerance and phytoremediation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrut, B.; Jean, S.; Silvestre, J.; Pinelli, E. Lead-induced DNA damage in Vicia faba root cells: Potential involvement of oxidative stress. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2011, 726, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, L.H.; Beardall, J. Effects of lead on two green microalgae Chlorella and Scenedesmus: Photosystem II activity and heterogeneity. Algal Res. 2016, 16, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleday, T.; Nilsson, R.; Jenssen, D. Arsenic [III] and heavy metal ions induce intrachromosomal homologous recombination in the hprt gene of V79 Chinese hamster cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2000, 35, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.M.; Mal, T.K. Effects of lead and copper exposure on growth of an invasive weed, Lythrum salicaria L. (Purple Loosestrife). Ohio J. Sci. 2003, 103, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul, G. Toxic effects of heavy metals on plant growth and metal accumulation in maize (Zea mays L.). Iran. J. Toxicol. 2010, 3, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, H.M.; Le, N.T.; Nguyen, K.H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Le, H.M.; Nguyen, A.T.; Dinh, N.T.T.; Hoang, S.A.; Van Ha, C. Copper nanoparticle application enhances plant growth and grain yield in maize under drought stress conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänsch, R.; Mendel, R.R. Physiological functions of mineral micronutrients (Cu, Zn, Mn, Fe, Ni, Mo, B, Cl). Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman Anik, T.; Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, M.M.; Keya, S.S.; Ha, C.V.; Khan, M.A.R.; Abdelrahman, M.; Dao, M.N.K.; Chu, H.D.; Tran, L.-S.P. Comparative effects of ZnSO4 and ZnO-NPs in improving cotton growth and yield under drought stress at early reproductive stage. Plant Sci. 2025, 359, 112589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, J.; Chatterjee, C. Management of phytotoxicity of cobalt in tomato by chemical measures. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, K.; Jaleel, C.A.; Municipality, A.; Emirates, E.; Emirates, A.; Arabia, S. Phytochemical changes in green gram (Vigna radiata) under cobalt stress. Glob. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 3, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Katare, J.; Pichhode, M.; Kumar, N. Growth of Terminalia bellirica [(Gaertn.) Roxb.] on the Malanjkhand copper mine overburden dump spoil material. Int. J. Res.-Granthaalayah 2015, 3, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Sairam, R.K.; Srivastava, G.C. Oxidative stress and antioxidative system in plants. Curr. Sci. 2002, 82, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar]

- De Dorlodot, S.; Lutts, S.; Bertin, P. Effects of ferrous iron toxicity on the growth and mineral composition of an interspecific rice. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, Z.; Ma, J.; Han, H. Toxicity of molybdenum-based nanomaterials on the soybean–rhizobia symbiotic system: Implications for nutrition. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 5773–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.S.A.; Ashraf, M. Essential roles and hazardous effects of nickel in plants. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 214, 125–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.R.; Cai, Q.S. Photosynthetic and anatomic responses of peanut leaves to zinc stress. Biol. Plant. 2009, 53, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Al-Whaibi, M.H.; Basalah, M.O. Interactive effect of calcium and gibberellin on nickel tolerance in relation to antioxidant systems in Triticum aestivum L. Protoplasma 2011, 248, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutzendubel, A.; Schwanz, P.; Teichmann, T.; Gross, K.; Langenfeld-Heyser, R.; Godbold, D.L.; Polle, A. Cadmium-induced changes in antioxidative systems, H2O2 content and differentiation in pine (Pinus sylvestris) roots. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Saifullah; Malhi, S.S.; Zia, M.H.; Naeem, A.; Bibi, S.; Farid, G. Role of mineral nutrition in minimizing cadmium accumulation by plants. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunaidi, A.A.; Lim, L.H.; Metali, F. Heavy metal tolerance and accumulation in the Brassica species (Brassica chinensis var. parachinensis and Brassica rapa L.): A pot experiment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourrut, B.; Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Winterton, P.; Pinelli, E. Lead uptake, toxicity, and detoxification in plants. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 213, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, M.F.; Sofy, M.R.; Mohamed, H.I.; Sofy, A.R.; Abdel-Kader, H.A. N-or/and P-deprived Coccomyxa chodatii SAG 216–2 extracts instigated mercury tolerance of germinated wheat seedlings. Plant Soil 2023, 483, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, H.E.; Fadhlallah, R.S. Impact of lead on seed germination, seedling growth, chemical composition, and forage quality of different varieties of Sorghum. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2023, 9, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. (Ed.) Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqeel, U.; Aftab, T.; Khan, M.M.A.; Naeem, M. Excessive copper induces toxicity in Mentha arvensis L. by disturbing growth, photosynthetic machinery, oxidative metabolism and essential oil constituents. Plant Stress 2023, 8, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadley, M.R.; White, P.J.; Hammond, J.P.; Zelko, I.; Lux, A. Zinc in plants. New Phytol. 2007, 173, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, J.; Panwar, R. Synergistic effect of pyrene and heavy metals (Zn, Pb, and Cd) on phytoremediation potential of Medicago sativa L. (alfalfa) in multi-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 21012–21027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Aslam, U.; Ferdous, S.; Qin, M.; Siddique, A.; Billah, M.; Naeem, M.; Mahmood, Z.; Kayani, S. Combined effect of endophytic Bacillus mycoides and rock phosphate on the amelioration of heavy metal stress in wheat plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wu, F.-B.; Zhang, G.-P. Effect of cadmium on growth and photosynthesis of tomato seedlings. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2005, 6, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Zuo, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Fang, X. Effects of heavy metal stress on physiology, hydraulics, and anatomy of three desert plants in the Jinchang mining area, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.N. Distribution and dynamics of electron transport complexes in cyanobacterial thylakoid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg 2016, 1857, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Duan, C. Effects of heavy metals on stomata in plants: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; Chwil, M. Lead-induced histological and ultrastructural changes in the leaves of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2005, 51, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, R.; Maruthavanan, J.; Ghoshroy, S.; Steiner, R.; Sterling, T.; Creamer, R. Physiological and ultrastructural effects of lead on tobacco. Biol. Plant. 2012, 56, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, A.; Farhan, M.; Sharif, F.; Hayyat, M.U.; Shahzad, L.; Ghafoor, G.Z. Effect of industrial wastewater on wheat germination, growth, yield, nutrients and bioaccumulation of lead. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosobrukhov, A.; Knyazeva, I.; Mudrik, V. Plantago major plants responses to increased content of lead in soil: Growth and photosynthesis. Plant Growth Regul. 2004, 42, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Growth and physiological responses of Pennisetum sp. to cadmium stress under three different soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 14867–14881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanishi, E.T.; Thomas, B.R.; Campbell, M.M. Drought induces alterations in the stomatal development program in Populus. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 4959–4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Kassem, E.; Sharaf-El-Din, A.; Rozema, J.; Foda, E.A. Synergistic effects of cadmium and NaCl on the growth, photosynthesis and ion content in wheat plants. Biol. Plant. 1995, 37, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.A.; Ashraf, U.; Khan, I.; Saleem, M.F. Chromium toxicity induced alterations in growth, photosynthesis, gas exchange attributes and yield formation in maize. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 53, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudsar, T.; Arshi, A.; Siddiqi, T.O.; Mahmooduzzafar; Iqbal, M. Zinc-induced changes in growth characters, foliar properties, and Zn-accumulation capacity of pigeon pea at different stages of plant growth. J. Plant Nutr. 2008, 31, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, C.; Lin, D.; Sun, Z.X. The effects of Cd on lipid peroxidation, hydrogen peroxide content and antioxidant enzyme activities in Cd-sensitive mutant rice seedlings. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2007, 87, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, R.; Dubey, R.S. Nickel-induced oxidative stress and the role of antioxidant defence in rice seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 59, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dubey, R.S. Lead toxicity induces lipid peroxidation and alters the activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice plants. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibra, M.G. Effects of mercury on some growth parameters of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Soil Environ. 2008, 27, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewska, E.; Bernat, P.; Długoński, J.; Skłodowska, M. Effect of nickel on membrane integrity, lipid peroxidation and fatty acid composition in wheat seedlings. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2012, 198, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Akhtar, M.J.; Zahir, Z.A.; Jamil, A. Effect of cadmium on seed germination and seedling growth of four wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Pak. J. Bot. 2012, 44, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Lukatkin, A.S.; Kashtanova, N.N.; Duchovskis, P. Changes in maize seedlings growth and membrane permeability under the effect of epibrassinolide and heavy metals. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2013, 39, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Seth, C.S. Photosynthesis, lipid peroxidation, and antioxidative responses of Helianthus annuus L. against chromium (VI) accumulation. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2022, 24, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.Y.; Sadiq, R.; Hussain, M.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmad, M.S.A. Toxic effect of nickel (Ni) on growth and metabolism in germinating seeds of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janas, K.M.; Zielińska-Tomaszewska, J.; Rybaczek, D.; Maszewski, J.; Posmyk, M.M.; Amarowicz, R.; Kosińska, A. The impact of copper ions on growth, lipid peroxidation, and phenolic compound accumulation and localization in lentil (Lens culinaris Medic.) seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, I.S.; Singal, H.R.; Singh, R. Effect of cadmium and nickel on photosynthesis and the enzymes of the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.). Photosynth. Res. 1990, 23, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, Z.R.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Kabir, M.; Shafiq, M. Toxic effects of lead and cadmium on germination and seedling growth of Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Upadhyay, N.; Kumar, N.; Yadav, G.; Singh, J.; Mishra, R.K.; Kumar, V.; Verma, R.; Upadhyay, R.G.; Pandey, M.; et al. Abscisic acid signaling and abiotic stress tolerance in plants: A review on current knowledge and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Fung, P.; Nishimura, N.; Jensen, D.R.; Fujii, H.; Zhao, Y.; Lumba, S.; Santiago, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Chow, T.-F.F.; et al. Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 2009, 324, 1068–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.K. Impact of copper on reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in Lemna minor. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustilli, A.C.; Merlot, S.; Vavasseur, A.; Fenzi, F.; Giraudat, J. Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 3089–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postiglione, A.E.; Muday, G.K. The role of ROS homeostasis in ABA-induced guard cell signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.M.; Murata, Y.; Benning, G.; Thomine, S.; Klusener, B.; Allen, G.J.; Grill, E.; Schroeder, J.I. Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 2000, 406, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, S.; Gupta, M. An update on nitric oxide and its benign role in plant responses under metal stress. Nitric Oxide 2017, 67, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linger, P.; Ostwald, A.; Haensler, J. Cannabis sativa L. growing on heavy metal contaminated soil: Growth, cadmium uptake and photosynthesis. Biol. Plant. 2005, 49, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamverdian, A.; Ding, Y. Effects of heavy metals’ toxicity on plants and enhancement of plant defense mechanisms of Si-mediation “review”. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Res. 2017, 3, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas, A.; Ullrich, C.I.; Sanz, A. Cd2+ effects on transmembrane electrical potential difference, respiration and membrane permeability of rice (Oryza sativa L.) roots. Plant Soil 2000, 219, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Mehrnia, M.; Azami, H.; Barzegari, D.; Shavandi, M.; Sarrafzadeh, M. Effect of heavy metals on fouling behavior in membrane bioreactors. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2010, 7, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.K.; Agrawal, M. Biological effects of heavy metals: An overview. J. Environ. Biol. 2005, 26, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.Z.; Fujita, M. Stress-induced changes of methylglyoxal level and glyoxalase I activity in pumpkin seedlings and cDNA cloning of glyoxalase I gene. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2009, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.Z.; Fujita, M. Up-regulation of antioxidant and glyoxalase systems by exogenous glycinebetaine and proline in mung bean confer tolerance to cadmium stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2010, 16, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Kumar, R.G.; Verma, S.; Dubey, R.S. Effect of cadmium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide anion generation and activities of antioxidant enzymes in growing rice seedlings. Plant Sci. 2001, 161, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M. Heavy metal stress in plants: A review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant defense system in plants: Reactive oxygen species production, signaling, and scavenging during abiotic Stress-Induced oxidative damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Dalal, N.S. Evidence for a Fenton-type mechanism for the generation of OH radicals in the reduction of Cr (VI) in cellular media. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990, 281, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jin, Z.Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, F. Physiological and biochemical responses to drought stress in cultivated and Tibetan wild barley. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 75, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Tito, N.; Giraldo, J.P. Anionic cerium oxide nanoparticles protect plant photosynthesis from abiotic stress by scavenging reactive oxygen species. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11283–11297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.I.; Ullah, I.; Toor, M.D.; Tanveer, N.A.; Din, M.M.U.; Basit, A.; Sultan, Y.; Muhammad, M.; Rehman, M.U. Heavy metals toxicity in plants: Understanding mechanisms and developing coping strategies for remediation: A review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DalCorso, G.; Farinati, S.; Maistri, S.; Furini, A. How plants cope with cadmium: Staking all on metabolism and gene expression. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, M.; Bhowmik, N.; Bandopadhyay, B.; Sharma, A. Comparison of mercury, lead and arsenic with respect to genotoxic effects on plant systems and the development of genetic tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 52, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, F.; Clijsters, H. Inhibition of photosynthesis in Phaseolus vulgaris by treatment with toxic concentrations of zinc: Effects on electron transport and photophosphorylation. Physiol. Plant. 1986, 66, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meharg, A.A.; Hartley-Whitaker, J. Arsenic uptake and metabolism in arsenic resistant and nonresistant plant species. New Phytol. 2002, 154, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quig, D. Cysteine metabolism and metal toxicity. Altern. Med. Rev. 1998, 3, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Chander, K.P.C.B.; Brookes, P.C.; Harding, S.A. Microbial biomass dynamics following addition of metal-enriched sewage sludges to a sandy loam. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillé, D.; Mollica-Nardo, V.; Giuffrè, O.; Ponterio, R.C.; Saija, F.; Sponer, J.; Trusso, S.; Cassone, G.; Foti, C. Binding of arsenic by common functional groups: An experimental and quantum-mechanical study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, J.; Boros, E.; Wyszkowska, J. Biochemical activity of nickel-contaminated soil. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2009, 18, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Kumchai, J.; Huang, J.Z.; Lee, C.Y.; Chen, F.C.; Chin, S.W. Proline partially overcomes excess molybdenum toxicity in cabbage seedlings grown in vitro. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 5589–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Effects of heavy metals on soil, plants, human health and aquatic life. Int. J. Res. Chem. Environ. 2011, 1, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jentschke, G.; Godbold, D.L. Metal toxicity and ectomycorrhizas. Physiol. Plant. 2000, 109, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyval, C.; Turnau, K.; Haselwandter, K. Effect of heavy metal pollution on mycorrhizal colonization and function: Physiological, ecological and applied aspects. Mycorrhiza 1997, 7, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.Á. Cellular mechanisms for heavy metal detoxification and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Polle, A.; Rennenberg, H.; Luo, Z.B. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of heavy metal accumulation in nonmycorrhizal versus mycorrhizal plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1087–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, N.S.; Bennett, A.E. Stressed out symbiotes: Hypotheses for the influence of abiotic stress on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Oecologia 2016, 182, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Sun, C.; Li, S.; Tauqeer, A.; Bian, X.; Shen, J.; Wu, S. The utilization and molecular mechanism of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in vegetables. Veg. Res. 2023, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, N.O.; Atayese, M.O.; Sakariyawo, O.S.; Azeez, J.O.; Sobowale, S.P.A.; Olubode, A.; Adeoye, S. Alleviation of heavy metal stress by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Glycine max (L.) grown in copper, lead and zinc contaminated soils. Rhizosphere 2021, 18, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, R.; Favas, P.J.; Pratas, J.; Varun, M.; Paul, M.S. Effect of Glomus mosseae on accumulation efficiency, hazard index and antioxidant defense mechanisms in tomato under metal(loid) stress. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2018, 20, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Kamran, M.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, H.; Yang, G.; Deng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Anastopoulos, I.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-induced mitigation of heavy metal phytotoxicity in metal contaminated soils: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowicz, V.A. Do arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alter plant–pathogen relations? Ecology 2001, 82, 3057–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd_Allah, E.F.; Hashem, A.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Bahkali, A.H.; Alwhibi, M.S. Enhancing growth performance and systemic acquired resistance of medicinal plant Sesbania sesban (L.) Merr using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under salt stress. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Hu, J.; Gong, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alleviate root damage stress induced by simulated coal mining subsidence ground fissures. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, A.A.; Bhalerao, S.A. Response of plants towards heavy metal toxicity: An overview of avoidance, tolerance and uptake mechanism. Ann. Plant Sci. 2013, 2, 362–368. [Google Scholar]

- Jarin, A.S.; Islam, M.M.; Rahat, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ghosh, P.; Murata, Y. Drought stress tolerance in rice: Physiological and biochemical insights. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 692–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, E.; Löffler, S.; Winnacker, E.L.; Zenk, M.H. Phytochelatins, the heavy-metal-binding peptides of plants, are synthesized from glutathione by a specific γ-glutamylcysteine dipeptidyl transpeptidase (phytochelatin synthase). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6838–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauser, W.E. Phytochelatins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1990, 59, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbett, C.S. Phytochelatin biosynthesis and function in heavy-metal detoxification. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Kneer, R.; Zhu, Y. Vacuolar compartmentalization: A second-generation approach to engineering plants for phytoremediation. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 9, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, S.; Kim, E.J.; Neumann, D.; Schroeder, J.I. Tolerance to toxic metals by a gene family of phytochelatin synthases from plants and yeast. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3325–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Guary, J.C.; Schoefs, B. How plants adapt their physiology to an excess of metals. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, D.E.; Rauser, W.E. MgATP-dependent transport of phytochelatins across the tonoplast of oat roots. Plant Physiol. 1995, 107, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbs, S.; Lau, I.; Ahner, B.; Kochian, L. Phytochelatin synthesis is not responsible for Cd tolerance in the Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens (J. & C. Presl). Planta 2002, 214, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsbrough, P. Metal tolerance in plants: The role of phytochelatins and metallothioneins. In Phytoremediation of Contaminated Soil and Water; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, K.; Hao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Mo, Y.; Rui, Y. Effects of Cerium Oxide on Rice Seedlings as Affected by Co-Exposure of Cadmium and Salt. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.S.; Dietz, K.J. The relationship between metal toxicity and cellular redox imbalance. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T.S.; Tzeng, S.S.; Yeh, K.W.; Yeh, C.H.; Chang, F.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Lin, C.Y. The heat-shock response in rice seedlings: Isolation and expression of cDNAs that encode class I low-molecular-weight heat-shock proteins. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993, 34, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollgiehn, R.; Neumann, D. Metal stress response and tolerance of cultured cells from Silene vulgaris and Lycopersicon peruvianum: Role of heat stress proteins. J. Plant Physiol. 1999, 154, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D.; Lichtenberger, O.; Günther, D.; Tschiersch, K.; Nover, L. Heat-shock proteins induce heavy-metal tolerance in higher plants. Planta 1994, 194, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Donkin, M.E.; Depledge, M.H. Hsp70 expression in Enteromorpha intestinalis (Chlorophyta) exposed to environmental stressors. Aquat. Toxicol. 2001, 51, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.M.; Sresty, T.V.S. Antioxidative parameters in the seedlings of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millspaugh) in response to Zn and Ni stresses. Plant Sci. 2000, 157, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schützendübel, A.; Polle, A. Plant responses to abiotic stresses: Heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1351–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, A.M.; Fulekar, M.H. Antioxidant enzyme responses of plants to heavy metal stress. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2012, 11, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okem, A.; Stirk, W.A.; Street, R.A.; Southway, C.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Effects of Cd and Al stress on secondary metabolites, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch. & C.A. Mey. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekzadeh, P.; Khara, J.; Farshian, S.; Jamal-Abad, A.K.; Rahmatzade, S. Cadmium toxicity in maize seedlings: Changes in antioxidant enzyme activities and root growth. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, N. Oxidative stress and change in plant metabolism of maize (Zea mays L.) growing in contaminated soil with elemental sulfur and toxic effect of zinc. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 57, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, F.; Wu, F.; Mao, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, M. Modulation of exogenous glutathione in antioxidant defense system against Cd stress in two barley genotypes differing in Cd tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.S.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Kumar, V. Root exudates ameliorate cadmium tolerance in plants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1243–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartwal, A.; Mall, R.; Lohani, P.; Guru, S.K.; Arora, S. Role of secondary metabolites and brassinosteroids in plant defense against environmental stresses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, K.A.; Djanaguiraman, M.; Sudhagar, R.; Chandrashekar, C.N.; Pathmanabhan, G. Differential antioxidative response of ascorbate-glutathione pathway enzymes and metabolites to chromium speciation stress in green gram (Vigna radiata L. cv. CO 4) roots. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhoudi, S.; Chaoui, A.; Ghorbal, M.H.; El Ferjani, E. Response of antioxidant enzymes to excess copper in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Plant Sci. 1997, 127, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.V.S.K.; Saradhi, P.P.; Sharmila, P. Concerted action of antioxidant enzymes and curtailed growth under zinc toxicity in Brassica juncea. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1999, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Qadri, T.N.; Siddiqi, T.O.; Iqbal, M. Differential activation of the enzymatic antioxidant system of Abelmoschus esculentus L. under CdCl2 and HgCl2 exposure. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 23, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.-B.; He, X.-J.; Chen, L.; Tang, L.; Gao, S.; Chen, F. Effects of zinc on growth and antioxidant responses in Jatropha curcas seedlings. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2010, 12, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Junior, R.A.; Moldes, C.A.; Delite, F.S.; Gratão, P.L.; Mazzafera, P.; Lea, P.J.; Azevedo, R.A. Nickel Elicits a Fast Antioxidant Response in Coffea arabica Cells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2006, 44, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odjegba, V.J.; Fasidi, I.O. Changes in antioxidant enzyme activities in Eichhornia crassipes (Pontederiaceae) and Pistia stratiotes (Araceae) under heavy metal stress. Rev. De Biol. Trop. 2007, 55, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boojar, M.M.A. Role of antioxidant enzyme responses and phytochelatins in tolerance strategies of Alhagi camelorum Fisch growing on copper mine. Acta Bot. Croat. 2010, 69, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Niekerk, L.A.; Gokul, A.; Basson, G.; Badiwe, M.; Nkomo, M.; Klein, A.; Keyster, M. Heavy metal stress and mitogen activated kinase transcription factors in plants: Exploring heavy metal–ROS influences on plant signalling pathways. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 2793–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Trivedi, P.K. Heavy metal stress signaling in plants. In Plant Metal Interaction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Mir, R.A.; Tyagi, A.; Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S.; Mushtaq, M.; Raina, A.; Park, S.; Sharma, S.; Mir, Z.A.; et al. Chromium toxicity in plants: Signaling, mitigation, and future perspectives. Plants 2023, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, D.; Trivedi, P.K.; Misra, P.; Tiwari, M.; Shri, M.; Shukla, D.; Kumar, S.; Rai, A.; Pandey, A.; Nigam, D.; et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of arsenate and arsenite stresses in rice seedlings. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Qi, J.; Dang, P.; Xia, T. Cadmium activates ZmMPK3-1 and ZmMPK6-1 via induction of reactive oxygen species in maize roots. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.Y.; Hu, F.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.R.; Liu, T. MAPKs regulate root growth by influencing auxin signaling and cell cycle-related gene expression in cadmium-stressed rice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 5449–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S.; Ali, A.; Kour, N.; Bornhorst, J.; AlHarbi, K.; Rinklebe, J.; Abd El Moneim, D.; Ahmad, P.; Chung, Y.S. Heavy Metal Induced Oxidative Stress Mitigation and ROS Scavenging in Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, N.-N.; Huang, T.-L.; Chi, W.-C.; Fu, S.-F.; Chen, C.-C.; Huang, H.-J. Chromium stress response effect on signal transduction and expression of signaling genes in rice. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 149, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Agarwal, P.; Roy, S. Plant response to heavy metal stress: An insight into the molecular mechanism of transcriptional regulation. In Plant Transcription Factors; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Cheng, Y.; Kanwar, M.K.; Chu, X.Y.; Ahammed, G.J.; Qi, Z.Y. Responses of plant proteins to heavy metal stress—A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Ö.; Ayan, A.; Meriç, S.; Atak, Ç. Heavy metal stress-responsive phyto-miRNAs. In Cellular and Molecular Phytotoxicity of Heavy Metals; Hasanuzzaman, M., Fujita, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kohli, S.K.; Khanna, K.; Dhiman, S.; Kour, J.; Bhardwaf, T.; Bhardwaf, R. Deciphering the role of metal binding proteins and metal transporters for remediation of toxic metals in plants. In Bioremediation of Toxic Metal(loid)s; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, W.J.; Sharma, S. Genomic instability in medicinal plants in response to heavy metal stress. In Stress-Responsive Factors and Molecular Farming in Medicinal Plants; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, B.; Ahmad, N.; Li, G.; Jalal, A.; Khan, A.R.; Zheng, X.; Du, D. Unlocking plant resilience: Advanced epigenetic strategies against heavy metal and metalloid stress. Plant Sci. 2024, 349, 112265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciano, S.; Mirouze, M. DNA methylation in rice and relevance for breeding. Epigenomes 2017, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Franco, J.J.; Sosa, C.C.; Ghneim-Herrera, T.; Quimbaya, M. Epigenetic control of plant response to heavy metal stress: A new view on aluminum tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 602625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.S.; Sun, C.C. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of the typical class III chitinase genes from three mangrove species under heavy metal stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Zheng, S.; Liu, R.; Lu, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Lue, C.; Zhang, L.; Yant, L.; et al. Genome-wide identification, phylogenetic and expression analysis of the heat shock transcription factor family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Mu, G.; Shen, Z.; Zheng, L. OsMYB45 plays an important role in rice resistance to cadmium stress. Plant Sci. 2018, 269, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapara, K.K.; Khedia, J.; Agarwal, P.; Gangapur, D.R.; Agarwal, P.K. SbMYB15 transcription factor mitigates cadmium and nickel stress in transgenic tobacco by limiting uptake and modulating antioxidative defence system. Functi. Plant Biol. 2019, 46, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, G. The walnut JrVHAG1 gene is involved in cadmium stress response through ABA-signal pathway and MYB transcription regulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Q.; Hasan, M.K.; Li, Z.; Yang, T.; Jin, W.; Qi, Z.; Yang, P.; Wang, G.; Ahammed, G.J.; Zhou, J. Melatonin-induced plant adaptation to cadmium stress involves enhanced phytochelatin synthesis and nutrient homeostasis in Solanum lycopersicum L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 456, 131670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, D.; Jia, L.; Huang, X.; Ma, G.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, A.; Guan, M.; Lu, K.; et al. Genome-wide identification and structural analysis of bZIP transcription factor genes in Brassica napus. Genes 2017, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Mitra, M.; Banerjee, S.; Roy, S. MYB4 transcription factor, a member of R2R3-subfamily of MYB domain protein, regulates cadmium tolerance via enhanced protection against oxidative damage and increases expression of PCS1 and MT1C in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2020, 297, 110501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X.; Ouyang, J.; Jiang, L.; Cao, S. WRKY12 represses GSH1 expression to negatively regulate cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 99, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Yan, X.; Huang, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Y.; Fan, T.; Xiao, F.; Liu, Y.; Cao, S. The WRKY transcription factor, WRKY13, activates PDR8 expression to positively regulate cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tong, C.; Cao, L.; Zheng, P.; Tang, X.; Wang, L.; Miao, M.; Liu, Y.; Cao, S. Regulatory module WRKY33–ATL31–IRT1 mediates cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, R.; Ju, Q.; Li, W.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Xu, J. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor MYB49 regulates cadmium accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharem, M.; Elkhatib, E.; Mesalem, M. Remediation of chromium and mercury polluted calcareous soils using nanoparticles: Sorption–desorption kinetics, speciation and fractionation. Environ. Res. 2019, 170, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Dai, H.; Hao, P.F.; Wu, F. Silicon regulates the expression of vacuolar H⁺-pyrophosphatase 1 and decreases cadmium accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Mobin, M.; Abbas, Z.K.; AlMutairi, K.A.; Siddiqui, Z.H. Role of nanomaterials in plants under challenging environments. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingyu, S.; Fashui, H.; Chao, L.; Xiao, W.; Xiaoqing, L.; Liang, C.; Zhongrui, L. Effects of nano-anatase TiO2 on absorption, distribution of light, and photoreduction activities of chloroplast membrane of spinach. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2007, 118, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, A.; Nangia, A.; Prasad, M.N.V. Cadmium and sodium adsorption properties of magnetite nanoparticles synthesized from Hevea brasiliensis bark: Relevance in amelioration of metal stress in rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 371, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Pan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Peijnenburg, W.J. Remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soil by biodegradable chelator–induced washing: Efficiencies and mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Adeel, M.; Shakoor, N.; Guo, M.; Hao, Y.; Azeem, I.; Rui, Y. Application of nanoparticles alleviates heavy metals stress and promotes plant growth: An overview. Nanomaterials 2020, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Lee, B.K. Influence of nano-TiO2 particles on the bioaccumulation of Cd in soybean plants (Glycine max), a possible mechanism for the removal of Cd from the contaminated soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 170, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, P.; Jayaraj, M.; Manikandan, R.; Geetha, N.; Rene, E.R.; Sharma, N.C.; Sahi, S.V. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) alleviate heavy metal-induced toxicity in Leucaena leucocephala seedlings: A physiochemical analysis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, A.M.; David Raju, M.; Rama Sekhara Reddy, D. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using aqueous root extract of Sphagneticola trilobata and its role in toxic metal removal and plant growth promotion. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2020, 50, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Wang, B.; Song, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Jiang, M. Astaxanthin and its gold nanoparticles mitigate cadmium toxicity in rice by inhibiting cadmium translocation and uptake. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Shen, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Wang, X. Impact of TiO2 nanoparticles on lead uptake and bioaccumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). NanoImpact 2017, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ye, F.; Zhang, H.; Hong, J.; Hua, C.; Wang, B.; Zhao, L. Metal(loid) oxides and metal sulfides nanomaterials reduced heavy metals uptake in soil cultivated cucumber plants. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konate, A.; He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, P.; Alugongo, G.M.; Rui, Y. Magnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles reduce heavy metals uptake and mitigate their toxicity in wheat seedling. Sustainability 2017, 9, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, R.; Ahmed, S.; Shah, A.A.; Yasin, N.A. Selenium nanoparticles reduced cadmium uptake, regulated nutritional homeostasis and antioxidative system in Coriandrum sativum grown in cadmium toxic conditions. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, N.; Jin, H. Foliar application of biosynthetic nano-selenium alleviates the toxicity of Cd, Pb, and Hg in Brassica chinensis by inhibiting heavy metal adsorption and improving antioxidant system in plant. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 240, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Chang, X.; Yang, Y.; Song, Z. Foliar graphene oxide treatment increases photosynthetic capacity and reduces oxidative stress in cadmium-stressed lettuce. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 154, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, Z.; Hassanshahian, M.; Cappello, S. Immobilization of microbes for bioremediation of crude oil polluted environments: A mini review. Open Microbiol. J. 2015, 9, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ken, D.S.; Sinha, A. Recent developments in surface modification of nano zero-valent iron (nZVI): Remediation, toxicity and environmental impacts. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 14, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaprakasam, P.; Jeena, S.E.; Premnath, D.; Selvaraju, T. Simple and robust green synthesis of Au NPs on reduced graphene oxide for the simultaneous detection of toxic heavy metal ions and bioremediation using bacterium as the scavenger. Electroanalysis 2016, 28, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rusyn, I.; Dmytruk, O.V.; Dmytruk, K.V.; Onyeaka, H.; Gryzenhout, M.; Gafforov, Y. Filamentous fungi for sustainable remediation of pharmaceutical compounds, heavy metal and oil hydrocarbons. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1106973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhjavani, M.; Nikkhah, V.; Sarafraz, M.M.; Shoja, S.; Sarafraz, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using green tea leaves: Experimental study on the morphological, rheological and antibacterial behaviour. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 53, 3201–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Alabresm, A.; Chen, Y.P.; Decho, A.W.; Lead, J. Improved metal remediation using a combined bacterial and nanoscience approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Puppa, L.; Komárek, M.; Bordas, F.; Bollinger, J.C.; Joussein, E. Adsorption of copper, cadmium, lead and zinc onto a synthetic manganese oxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 399, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.I.; Tani, Y.; Chang, J.; Miyata, N.; Naitou, H.; Seyama, H. As (III) oxidation kinetics of biogenic manganese oxides formed by Acremonium strictum strain KR21-2. Chem. Geol. 2013, 347, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Sadaf, I.; Rafique, M.S.; Tahir, M.B. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1272–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, T.; Joerger, R.; Olsson, E.; Granqvist, C.G. Silver-based crystalline nanoparticles, microbially fabricated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13611–13614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Anwar, F.; Janjua, M.R.S.A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Rashid, U. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles through reduction with Solanum xanthocarpum L. berry extract: Characterization, antimicrobial and urease inhibitory activities against Helicobacter pylori. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 9923–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Senani, G.M.; Al-Kadhi, N. The synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the adsorption of Cu2+ from aqueous solutions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shedbalkar, U.; Singh, R.; Wadhwani, S.; Gaidhani, S.; Chopade, B.A. Microbial synthesis of gold nanoparticles: Current status and future prospects. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 209, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, A.; Jain, N.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Panwar, J. Development of gold nanoparticle-fungal hybrid based heterogeneous interface for catalytic applications. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.S.; Ahmad, A.; Pasricha, R.; Sastry, M. Bioreduction of chloroaurate ions by geranium leaves and its endophytic fungus yields gold nanoparticles of different shapes. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 1822–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, H.; Kumar, S.V.; Rajeshkumar, S. A review on green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles—An eco-friendly approach. Resour.-Effic. Technol. 2017, 3, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Abdallah, Y.; Ali, M.A.; Masum, M.M.I.; Li, B.; Sun, G.; An, Q. Lemon-fruit-based green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and titanium dioxide nanoparticles against soft rot bacterial pathogen Dickeya dadantii. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, D.; Hennebel, T.; Taghavi, S.; Mast, J.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W.; Fitts, J.P. Concomitant microbial generation of palladium nanoparticles and hydrogen to immobilize chromate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7635–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyam, V.; Subashchandrabose, S.R.; Thavamani, P.; Megharaj, M.; Chen, Z.; Naidu, R. Chlorococcum sp. MM11—A novel phyco-nanofactory for the synthesis of iron nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, J.C.; Raliya, R. Rapid, low-cost, and ecofriendly approach for iron nanoparticle synthesis using Aspergillus oryzae TFR9. J. Nanopart. 2013, 2013, 141274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Dhankher, O.P.; Tripathi, R.D.; Seth, C.S. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles potentially regulate the mechanisms for photosynthetic attributes, genotoxicity, antioxidants defense machinery, and phytochelatins synthesis in relation to hexavalent chromium toxicity in Helianthus annuus L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, T.; Liang, J.; Qu, J. The role of biogenic Fe-Mn oxides formed in situ for arsenic oxidation and adsorption in aquatic ecosystems. Water Res. 2016, 98, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Dalei, K.; Chakraborty, J.; Das, S. Extracellular polymeric substances of a marine bacterium mediated synthesis of CdS nanoparticles for removal of cadmium from aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 462, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

, heavy metals. Figure created using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

, heavy metals. Figure created using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

, heavy metals. Figure created using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

, heavy metals. Figure created using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

| Metals | Essentiality and Roles in Plants | Adequate/Beneficial Levels (mg kg−1 DW) | Toxic Levels (mg kg−1 DW) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Non-essential toxic heavy metal | – | ≥5 | [60] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | – | ≥5 | [60,61] | |

| Chromium (Cr) | – | ≥5 | [62] | |

| Mercury (Hg) | – | ≥1 | [60,63] | |

| Lead (Pb) | – | ≥30 | [62,64] | |

| Copper (Cu) | Essential micronutrient | 5–30 | >30 | [65,66] |

| Iron (Fe) | 50–250 | >500 | [65] | |

| Manganese (Mn) | 20–500 | >1000 | [65] | |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.1–5 | >10 | [65] | |

| Zinc (Zn) | 25–150 | >150 | [67,68] | |

| Nickel (Ni) | 0.1–10 | >50 | [69,70] | |

| Cobalt (Co) | Beneficial for nitrogen fixation in legumes | 0.02–2 | >10 | [65] |

| Plants | HM Stresses | Morphological, Physiological, and Biochemical Responses | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Cd | Reduces catalase activity, which impairs H2O2 scavenging, resulting in higher lipid peroxide levels | [84] |

| Ni | Increases the level of H2O2 and TBARS | [85] | |

| Pb | Increases lipid peroxidation | [86] | |

| Hg | Decreases canopy height, tillers number, panicle length, and yield | [87] | |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Ni | Increases electrolyte leakage and lipid peroxidation | [88] |

| Cd | Reduces shoot and root development | [89] | |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Zn and Ni | Intensifies lipid peroxidation and decrease in permeability of cell membranes | [90] |

| Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) | Cr | Increases lipid peroxidation by stimulating production of malondialdehyde and H2O2 | [91] |

| Ni | Inhibits mobilization of stored proteins and amino acids; reduces α-amylase and protease activity | [92] | |

| Lentil (Lens culinaris) | Cu | Increases lipid peroxidation in roots | [93] |

| Pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) | Cd and Ni | Reduces photosynthetic activity | [94] |

| Siris tree (Albizia lebbeck) | Cd and Pb | Cd impairs seedling development and elongation; Pb disrupts stored food material and reduces germination rate | [95] |

| Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) | Cd | Reduces shoot and root biomass and decreases total chlorophyll content in the leaves | [96] |

| Silene compecta and Thalpsi ochrolucum | Cu | Damages the electron transport chain involved in photosynthesis | [97] |

| Thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) | Cd | Increases lipid peroxidation | [98] |

| Duckweed (Lemna minor) | Cu | [99] |

| Plants | HM | Antioxidant Enzymes Response | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maize (Zea mays) | Cd | Increases APX and GPX activities | [162] |

| Zn | SOD and POD activities increase, while CAT activity decreases at higher Zn levels | [163] | |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | Cd | Increases activities of APX and GPX | [164] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Pb | Elevates guaiacol peroxidase, SOD, and GR activities | [86] |

| Mung bean (Vigna radiata) | Cr | APX activity increases, which helps reduce H2O2 accumulation | [169] |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) | Cu | Increases the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT | [170] |

| Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) | Zn | Increases CAT activity, which scavenges H2O2 and reduces oxidative stress | [171] |

| Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) | Hg | Increases SOD, APX, and GR activities and decreases CAT activity | [172] |

| Peregrina (Jatropha integerrima) | Zn | POD and CAT activities increase with Zn concentration | [173] |

| Coffee (Coffea arabica) | Increases GR activity, which supports GSH levels for PC biosynthesis | [174] | |

| Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) | CAT activity increases with Ag, Cd, Cr, Pb, and Cu | [175] | |

| Camelthorn (Alhagi camelorum) | Cu | Induces PC synthesis and depletes total GSH activity | [176] |

| Signaling Pathways | Key Components | Heavy Metals | Responses | Genes Involved | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium-dependent signaling | Ca2+ channels, calmodulins (CaMs), calmodulin-like proteins (CMLs), calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs)/CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs) | Cr, As, Pb, Cu | Calcium influx triggers antioxidant enzyme activation (e.g., SOD, APX); regulates redox homeostasis; CDPKs and CaMs modulate downstream responses | AtCBL1, CDPK-like kinases, CAMs | [178,179,180] |

| MAPK cascade signaling | MAPKKK → MAPKK → MAPK (MPKs) | Cd, Cu, As, Cr | Phosphorylation of TFs (WRKY, DREB, bZIP, MYB); modulation of stress-responsive genes; interaction with HSPs for defense | OsMAPK2, ZmMPK3/6, WRKY, ERF, bZIP, MYB | [177,181,182] |

| ROS signaling | ROS (O2–, H2O2, OH−), antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX), thiol metabolism enzymes | Cd, Cr, As, Pb | Low ROS levels act as signaling molecules; high ROS induce PCD; upregulation of antioxidant genes maintains ROS balance | OsGSTL2, OsMATE1/2, DHAR, GR, SOD, CAT | [178,183] |

| Hormonal Signaling | ABA, JA, ET, SA, EIN2/3, JAZ, AP2/ERF transcription factors | Cd, Cr, As | Phytohormones regulate transcription and crosstalk with MAPK cascades; influence root development and HM detoxification | AP2/ERF, ACS, OsARM1, AtMYB, AB15, TGAL3 | [180,184] |

| Crosstalk and integration | Interactions among Ca2+, ROS, MAPKs, hormones, nitric oxide | Cd, Pb, As, Cr, Cu | Synergistic and antagonistic interactions among signaling pathways coordinate stress responses; modulate TF networks | Multigene families: WRKY, bZIP, HSF, MYB, ERF | [177,178] |

| Plants | TFs | Gene(s) | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | HSF | TaHsfA4a | Upregulates metallothionein genes under Cd stress | [194] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | MYB | OsMYB45 | Downregulation increases Cd sensitivity; regulates antioxidant activity | [182,195] |

| bZIP | - | Involved in auxin and HM signaling crosstalk | ||

| WRKY | - | Activated by MAPK pathways under HM stress | ||

| Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) | MYB | SbMYB15 | Confers Cd and Ni stress tolerance | [196] |

| Walnut (Juglans regia) | MYB | JrMYB2 | Improves tolerance to Cd stress | [197] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | HSF | HSF1A | Induces melatonin biosynthesis for Cd tolerance | [198] |

| Rapeseed (Brassica napus) | bZIP | BnbZIP2, BnbZIP3 | Upregulated under drought and Cd; involved in stress signaling | [199] |

| Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | MYB | AtMYB4 | Improves antioxidant defense under Cd stress | [200] |

| WRKY | AtWRKY12 | Downregulated under Cd; represses GSH1 to negatively regulate Cd tolerance | [201] | |

| WRKY | AtWRKY13 | Upregulated under Cd; activates PDR8 to positively regulate Cd tolerance | [202] | |

| WRKY | WRKY33 | Regulates HM uptake via IRT1 regulation under Cd stress | [203] | |

| bZIP | AB15 | Interacts with MYB49 to reduce Cd uptake via IRT1 inactivation | [204] |

| Nanoparticles | Plant Species | HMs | Reduction of HMs (%) | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc oxide (ZnO) | Rice, fenugreek, and Leucaena leucocephala | Pb, Cd, Cr, Cu | Pb: 79–85; Cd: 80–87; Cr: 38–81; Cu: 60 | Improves growth and Zn uptake; reduces HM accumulation | [213,214] |

| Cerium oxide (CeO2) | Rice | Cd | 8.4 | Reduces growth inhibition and oxidative stress | [152] |

| Astaxanthin-functionalized gold (Ast-Au) NPs | 26–86 | Enhances chlorophyll content and amino acid metabolism; scavenges ROS | [215] | ||

| Titanium dioxide (TiO2) | Rice and cucumber | Pb, As, Al | 34–97 | Reduces HM contamination and toxicity | [216] |

| Iron oxide (Fe3O4) | Wheat | Pb, Zn, Cd, Cu | Roots: 24–68; Shoots: 11–100 | Reduces oxidative stress and growth suppression | [217,218] |

| Selenium NPs (Se, Bio-Se) | Coriander and pak choi | Cd, Pb, Hg | Cd: 21–31; Pb: 5–30; Hg: 3–23 | Enhances antioxidant defense; reduces HM uptake | [219,220] |

| Graphene oxide | Lettuce | Cd | - | Reduces Cd toxicity; improves photosynthesis, chlorophyll content, antioxidant enzymes, and biomass | [221] |

| Nanoparticles | Microorganisms/Plant Extracts Used | Alleviation of Phytotoxicity/Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver NPs | Escherichia coli | Rapid reduction of Ag+ ions within minutes | [230] |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | Silver-resistant; accumulates silver and reduces its toxicity | [231] | |

| Solanum xanthocarpum (berry extract) | Enhances Ag+ ion reduction rate via phytochemicals | [232] | |

| Convolvulus arvensis (leaf extract) | Achieves 98.99% Cu2+ ion removal via adsorption | [233] | |

| Gold NPs | Bacillus subtilis | Acts as a biocontrol agent with antifungal properties | [234] |

| Aspergillus japonicus | Reduces Au(III) to Au(0); immobilized AuNPs | [235] | |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Reduces and caps gold NPs | [236] | |

| ZnO NPs | Green algae | Converts metal ions into zero-valent metals via phytochemicals | [237] |

| Citrus limon (leaf extract) | Non-toxic synthesis; biomolecule-rich extract enhances safety | [238] | |

| Lead NPs | Clostridium pasteurianum | Reduces Cr(VI) to Cr(III); ~70% remediation efficiency | [239] |

| Iron NPs | Chlorococcum (alga) | Biosynthesized Fe NPs removed 92% Cr vs. 25% by bulk Fe | [240] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Cost-effective and eco-friendly NP synthesis for remediation | [241] | |

| TiO2 NPs | Aspergillus niger | Reduces Cr(VI) toxicity and DNA damage in Helianthus annuus by minimizing total Cr uptake | [242] |

| Biogenic Fe–Mn oxides (BFMO) | Pseudomonas sp. | Converts As(III) to less mobile As(V); enhances arsenic remediation | [243] |

| CdS NPs | P. aeruginosa | EPS-enriched CdS NPs enhance cadmium ion adsorption and stabilization | [244] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarin, A.S.; Khan, M.A.R.; Apon, T.A.; Islam, M.A.; Rahat, A.; Akter, M.; Anik, T.R.; Nguyen, H.M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ha, C.V.; et al. Plant Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses: Mechanisms, Defense Strategies, and Nanoparticle-Assisted Remediation. Plants 2025, 14, 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243834

Jarin AS, Khan MAR, Apon TA, Islam MA, Rahat A, Akter M, Anik TR, Nguyen HM, Nguyen TT, Ha CV, et al. Plant Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses: Mechanisms, Defense Strategies, and Nanoparticle-Assisted Remediation. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243834

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarin, Aysha Siddika, Md Arifur Rahman Khan, Tasfiqure Amin Apon, Md Ashraful Islam, Al Rahat, Munny Akter, Touhidur Rahman Anik, Huong Mai Nguyen, Thuong Thi Nguyen, Chien Van Ha, and et al. 2025. "Plant Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses: Mechanisms, Defense Strategies, and Nanoparticle-Assisted Remediation" Plants 14, no. 24: 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243834

APA StyleJarin, A. S., Khan, M. A. R., Apon, T. A., Islam, M. A., Rahat, A., Akter, M., Anik, T. R., Nguyen, H. M., Nguyen, T. T., Ha, C. V., & Tran, L.-S. P. (2025). Plant Responses to Heavy Metal Stresses: Mechanisms, Defense Strategies, and Nanoparticle-Assisted Remediation. Plants, 14(24), 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243834