Moderate Shading Improves Growth, Photosynthesis, and Physiological Traits in Spuriopinella brachycarpa (Kom.) Kitag.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Shading on Plant Height

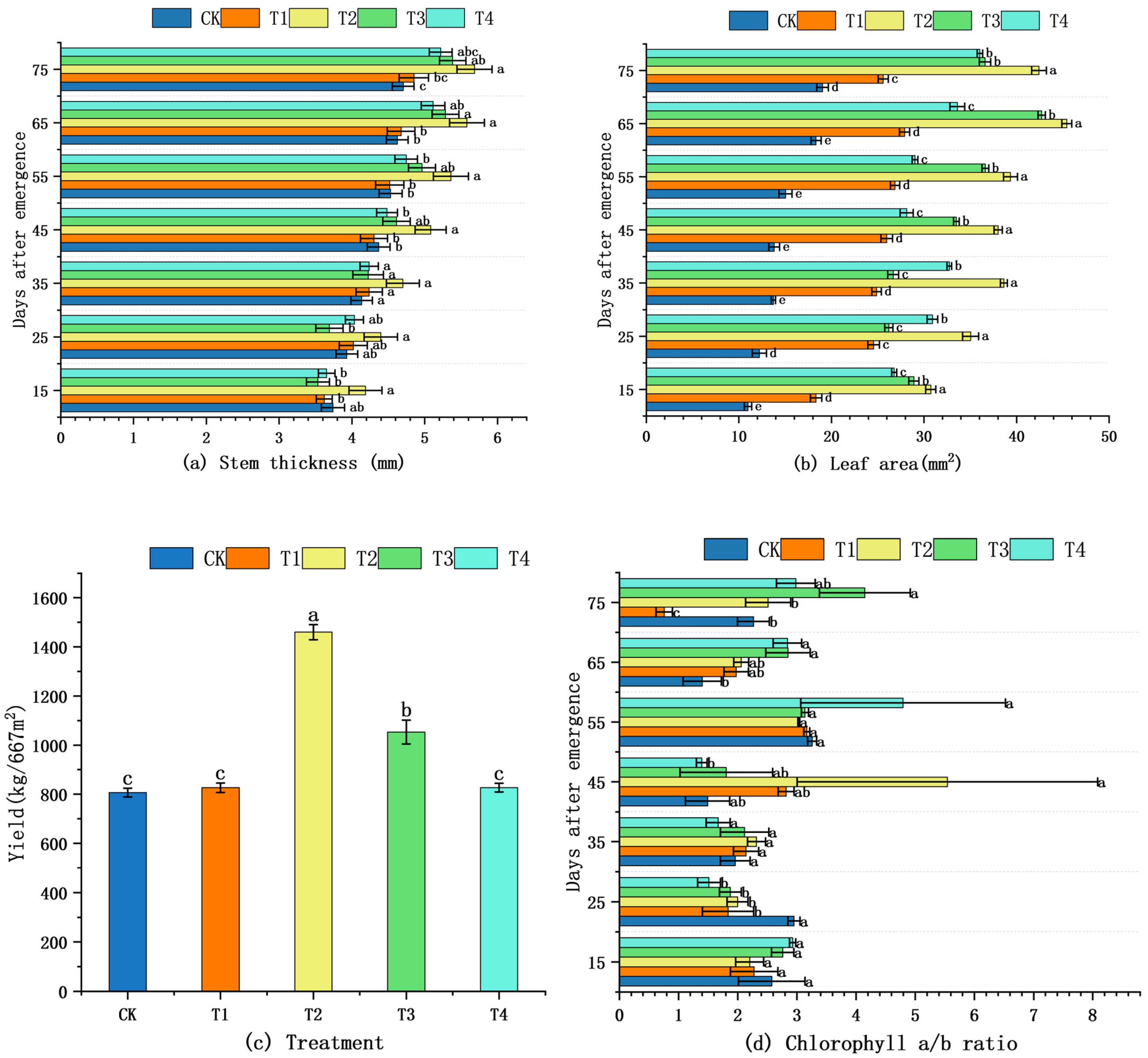

2.2. Effects of Shading on Morphological and Biochemical Traits

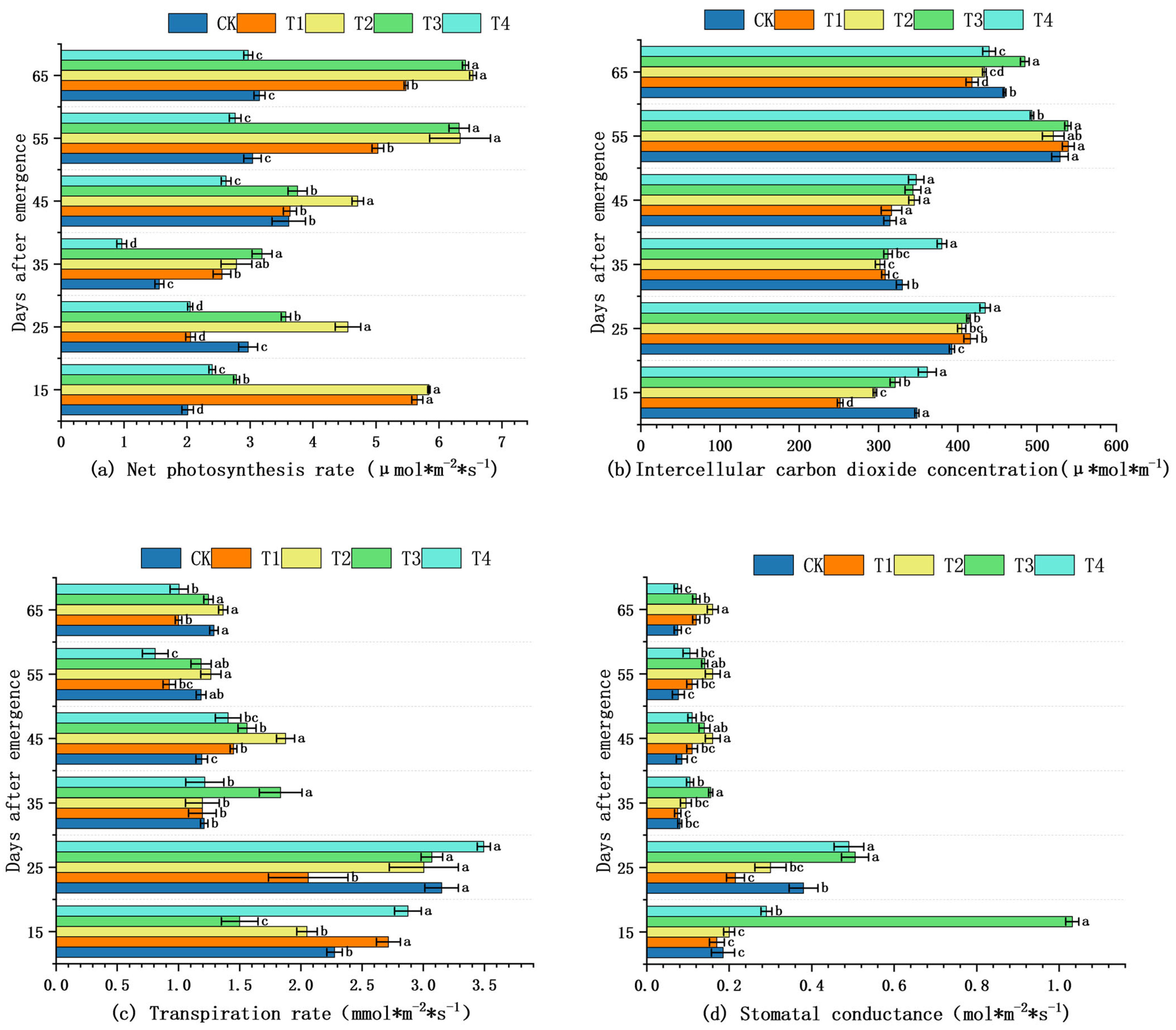

2.3. Effects of Shading on Gas Exchange

2.4. Effects of Shading on PSII Efficiency and Fluorescence Quenching

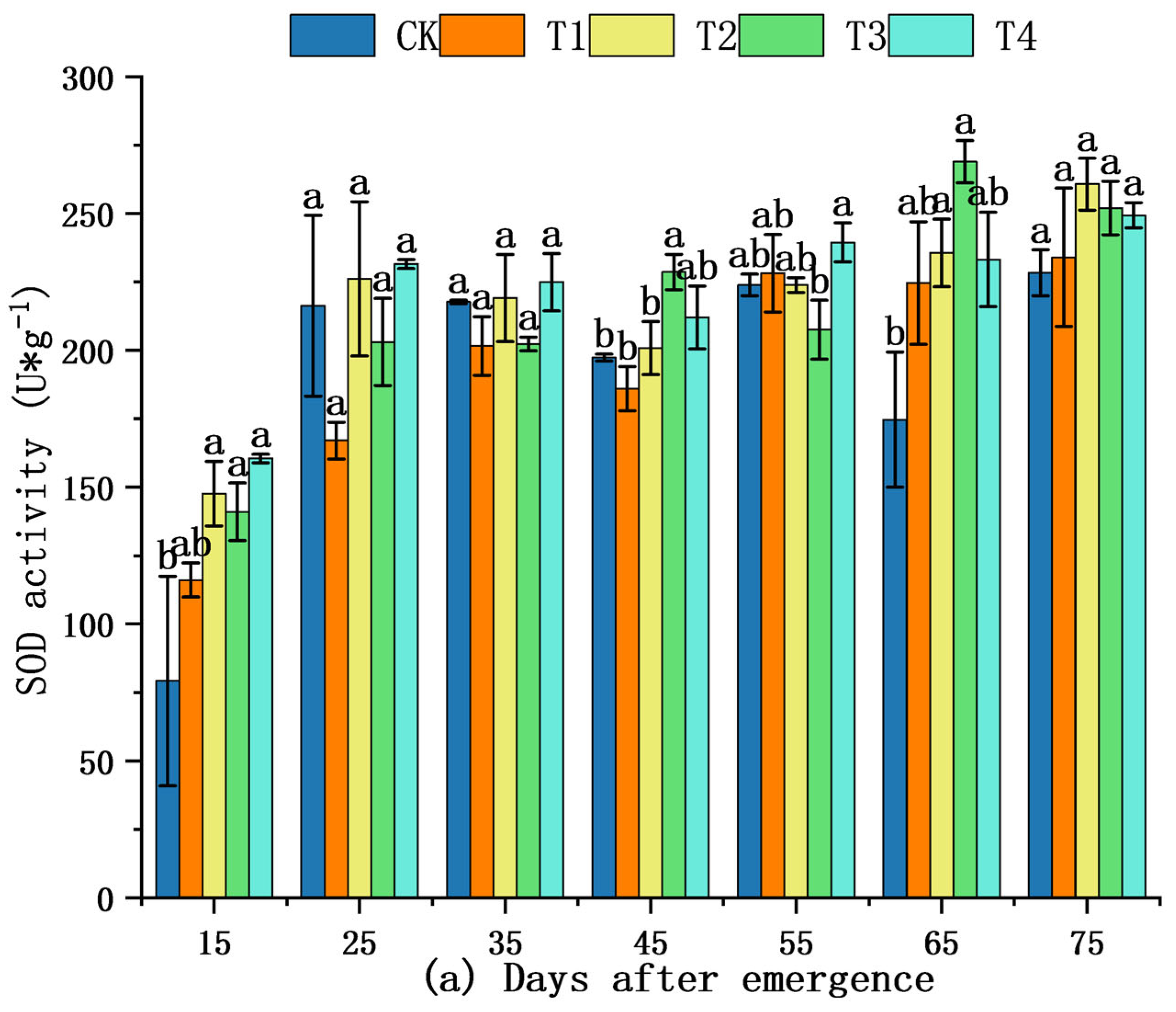

2.5. Effect of Shading on Antioxidant Enzymes

3. Material and Method

3.1. Site Description

3.2. Experimental Design

3.3. Test Method

3.3.1. General Protocol for All Physiological Measurements

3.3.2. Determination of Morphological Traits

3.3.3. Determination of Commercial Yield

3.3.4. Determination of Quality Traits

3.3.5. Determination of Photosynthetic Parameters

3.3.6. Determination of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

3.3.7. Determination of Antioxidant Enzymes

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sample | Days After Emergence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 15d | 25d | 35d | |

| CK | 16.78 ± 0.27a | 18.26 ± 0.08ab | 19.34 ± 0.14d |

| T1 | 14.12 ± 0.28c | 18.66 ± 0.15a | 20.24 ± 0.15bc |

| T2 | 14.96 ± 0.50bc | 18.50 ± 0.21ab | 21.78 ± 0.28a |

| T3 | 15.90 ± 0.30ab | 18.08 ± 0.23b | 20.96 ± 0.40b |

| T4 | 16.32 ± 0.32a | 17.94 ± 0.20b | 19.68 ± 0.29cd |

References

- Eriksson, P.G.; Altermann, W.; Nelson, D.R.; Mueller, W.U.; Catuneanu, O. Evolution of life and Precambrian bio-geology. Dev. Precambrian Geol. 2004, 15, 513–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, R.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Cho, Y.B.; Ermakova, M.; Harbinson, J.; Lawson, T.; McCormick, A.J.; Niyogi, K.K.; Ort, D.R.; Patel-Tupper, D.; et al. Perspectives on improving photosynthesis to increase crop yield. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3944–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslam, M.; Mitsui, T.; Hodges, M.; Priesack, E.; Herritt, M.T.; Aranjuelo, I.; Sanz-Sáez, Á. Photosynthesis in a changing global climate: Scaling up and scaling down in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.N.; Lantzke, N.; van Burgel, A. Effects of shade nets on microclimatic conditions, growth, fruit yield, and quality of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.): A case study in Carnarvon, Western Australia. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Su, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, M.; Yang, B.; Wan, W.; Wen, X.; Yang, S.; Ding, X.; Zou, J. Effect of red and blue light on cucumber seedlings grown in a plant factory. Horticulturae 2020, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niinemets, Ü.; Ntagkas, N.; Siebenkäs, A.; Mäenpää, M.; Matsubara, S.; Pons, T. A meta-analysis of plant responses to light intensity for 70 traits ranging from molecules to whole plant performance. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1073–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Viveros, Y.; Valiente-Banuet, J.I. Colored shading nets differentially affect the phytochemical profile, antioxidant capacity, and fruit quality of piquin peppers (Capsicum annuum L. var. glabriusculum). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of drought stress on the photosynthesis of wild apricot. Acta Hortic. 2008, 769, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.; Han, Y.; Mao, S.; Wang, G.; Feng, L.; Yang, B.; Fan, Z.; Du, W.; Lu, J.; Li, Y. Light spatial distribution in the canopy and crop development in cotton. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyukaryeva, V.; Mallik, A.U. Shade effect on phenology, fruit yield, and phenolic content of two wild blueberry species in Northwestern Ontario, Canada. Plants 2023, 12, 4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.L.; Guo, Y.K.; Bai, J.G.; Shang, L.; Wang, X.J. Effects of long-term chilling on ultrastructure and antioxidant activity in leaves of two cucumber cultivars under low light. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 132, 467–478. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18334000/ (accessed on 12 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Luo, S.; Pan, J.; Yao, S.; Gao, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, G. Light regimes regulate leaf and twigs traits of Camellia oleifera (Abel) in Pinus massoniana plantation understory. Forests 2022, 13, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Song, L.; Yu, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Ying, Y. Growth, physiological, and biochemical responses of Camptotheca acuminata seedlings to different light environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, C.A.; Riadh, K.; Gopi, R.; Manivannan, P.; Inès, J.; Al-Juburi, H.J.; Zhao, C.-X.; Shao, H.-B.; Panneerselvam, R. Antioxidant defense responses: Physiological plasticity in higher plants under abiotic constraints. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2009, 31, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, T.; Tanouchi, A.; Tamoi, M.; Yabuta, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Shigeoka, S. Arabidopsis chloroplastic ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes play a dual role in photoprotection and gene regulation under photooxidative stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 51, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Zhai, W.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Liu, J.; Ren, L.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y. Effects of low light on photosynthetic properties, antioxidant enzyme activity, and anthocyanin accumulation in purple pak-choi (Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis Makino). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, A.H.; Nie, Y.X.; Yu, B.; Li, Q.; Lu, L.Y.; Bai, J.G. Cinnamic acid pretreatment enhances heat tolerance of cucumber leaves through modulating antioxidant enzyme activity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Qian, W.; Xu, L.; Huang, G.; Cong, W.; Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Wang, D.; Guan, S. Phytochemical composition and toxicity of an antioxidant extract from Pimpinella brachycarpa (Kom.) Nakai. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 34, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Li, X.; Lin, L.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Wang, B. The effects of shade on leaf traits and water physiological characteristics in Alhagi sparsifolia. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 8466–8474. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, I.B.; Seo, T.C.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.S. Growth and photosynthetic responses to increased LED light intensity in Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) sprouts. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 207, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, N.; Giannopolitis, C.N.; Stanley, K.; Ries, S. Superoxide dismutases: II. Purification and quantitative relationship with water-soluble protein in seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutase assays in plants: A re-evaluation of the NBT method. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2011.

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, L.; Wei, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, X. Physiological, morphological, and anatomical changes in Rhododendron agastum in response to shading. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 81, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberti, I.; Sessa, G.; Ciolfi, A.; Possenti, M.; Carabelli, M.; Morelli, G. Plant adaptation to dynamically changing environment: The shade avoidance response. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semchenko, M.; Lepik, M.; Götzenberger, L.; Zobel, K. Positive effect of shade on plant growth: Amelioration of stress or active regulation of growth rate. J. Ecol. 2012, 100, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.Y.; Díaz-Pérez, J.C.; Nambeesan, S.U. Effect of shade levels on plant growth, physiology, and fruit yield in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Acta Hortic. 2022, 1268, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Feng, L.Y.; Iqbal, N.; Khan, I.; Meraj, T.A.; Xi, Z.J.; Naeem, M.; Ahmed, S.; Sattar, M.T.; Chen, Y.K.; et al. Effects of contrasting shade treatments on the carbon production and antioxidant activities of soybean plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 2020, 47, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Li, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Luo, H.; Lu, M.; Lu, K.; et al. Effects of different shade treatments on Melaleuca seedling growth and physiological properties. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Lu, J.; Yang, H. Effects of shading on the growth and leaf photosynthetic characteristics of three forages in an apple orchard on the Loess Plateau of eastern Gansu, China. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hannaway, D.; Lu, H. Effects of shade treatments on the photosynthetic capacity, chlorophyll fluorescence, and chlorophyll content of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 65, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, K. The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: Scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1999, 50, 601–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Kruk, J.; Górecka, M.; Karpińska, B.; Karpiński, S. Evidence for light wavelength-specific photoelectrophysiological signaling and memory of excess light episodes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, F.; Wei, S.Q.; Liu, N.; Xu, L.J.; Yang, P. Growth of cucumber seedlings in different varieties as affected by light environment. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2020, 13, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartold, M.; Kluczek, M. Estimating of chlorophyll fluorescence parameter Fv/Fm for plant stress detection at peatlands under Ramsar Convention with Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jiang, M.; Yue, Q.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Lv, B.; He, R.; Feng, S.; Yang, M. Effects of low-light environments on the growth and physiological and biochemical parameters of indocalamus and seasonal variations in leaf active substance contents. Plants 2023, 12, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Chu, X.; Gou, K.J.; Jiang, D.X.; Li, Q.Q.; Lv, C.G.; Gao, Z.P.; Chen, G.X. The photosynthetic function analysis for leaf photooxidation in rice. Photosynthetica 2023, 61, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, R.; Sun, Z.; Wang, M.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; et al. Effects of shading on morphology, photosynthesis characteristics, and yield of different shade-tolerant peanut varieties at the flowering stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1429800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valladares, F.; Niinemets, Ü. Shade tolerance, a key plant feature of complex nature and consequences. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ge, J.; Dayananda, B.; Li, J. Effect of light intensities on the photosynthesis, growth and physiological performances of two maple species. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 999026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Zhou, L.; Liao, X.H.; Zhang, K.Y.; Aer, L.S.; Yang, E.L.; Deng, J.; Zhang, R.P. Effects of low light after heading on the yield of direct seeding rice and its physiological response mechanism. Plants 2023, 12, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Dong, W.; Gu, L. Determinants of photochemical characteristics of the photosynthetic electron transport chain of maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1279963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.; Li, X.P.; Niyogi, K.K. Non-photochemical quenching: A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Ghanizadeh, H.; Kerckhoffs, H.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Wu, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; et al. Comparative genomic and physiological analyses of a superoxide dismutase mimetic (SODm-123) for its ability to respond to oxidative stress in tomato plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13608–13619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhamdi, A.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev164376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Li, P.; Wu, Y.; Tang, J. Effects of different light intensities on anti-oxidative enzyme activity, quality and biomass in lettuce. Hort. Sci. 2012, 39, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didaran, F.; Kordrostami, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. The mechanisms of photoinhibition and repair in plants under high light conditions and interplay with abiotic stressors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2024, 259, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Days After Emergence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45d | 55d | 65d | 75d | |

| CK | 20.12 ± 0.23a | 21.5 ± 0.68a | 21.50 ± 0.95a | 20.2 ± 0.18a |

| T1 | 21.08 ± 0.25a | 22.26 ± 0.52a | 22.72 ± 0.45a | 22.64 ± 0.09a |

| T2 | 22.44 ± 0.53a | 24.84 ± 0.31a | 26.88 ± 0.83a | 26.44 ± 0.44a |

| T3 | 22.60 ± 0.43a | 24.80 ± 0.54a | 27.30 ± 0.44a | 26.72 ± 0.45a |

| T4 | 21.42 ± 0.46a | 24.04 ± 0.90a | 26.44 ± 1.18a | 24.68 ± 0.79a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.; Zou, Y.; Qi, Q.; Zhao, C.; Liu, S.; Qiao, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Zou, Y.; et al. Moderate Shading Improves Growth, Photosynthesis, and Physiological Traits in Spuriopinella brachycarpa (Kom.) Kitag. Plants 2025, 14, 3824. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243824

Chen S, Zou Y, Qi Q, Zhao C, Liu S, Qiao J, Yu Y, Zhao J, Li S, Zou Y, et al. Moderate Shading Improves Growth, Photosynthesis, and Physiological Traits in Spuriopinella brachycarpa (Kom.) Kitag. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3824. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243824

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Shanshan, Yan Zou, Qin Qi, Chunbo Zhao, Shuang Liu, Jianlei Qiao, Yue Yu, Jing Zhao, Shuang Li, Yue Zou, and et al. 2025. "Moderate Shading Improves Growth, Photosynthesis, and Physiological Traits in Spuriopinella brachycarpa (Kom.) Kitag." Plants 14, no. 24: 3824. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243824

APA StyleChen, S., Zou, Y., Qi, Q., Zhao, C., Liu, S., Qiao, J., Yu, Y., Zhao, J., Li, S., Zou, Y., Li, X., Teng, J., Lv, H., & Yang, B. (2025). Moderate Shading Improves Growth, Photosynthesis, and Physiological Traits in Spuriopinella brachycarpa (Kom.) Kitag. Plants, 14(24), 3824. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243824