The Role of Plant-Derived Essential Oils in Eco-Friendly Crop Protection Strategies Under Drought and Salt Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

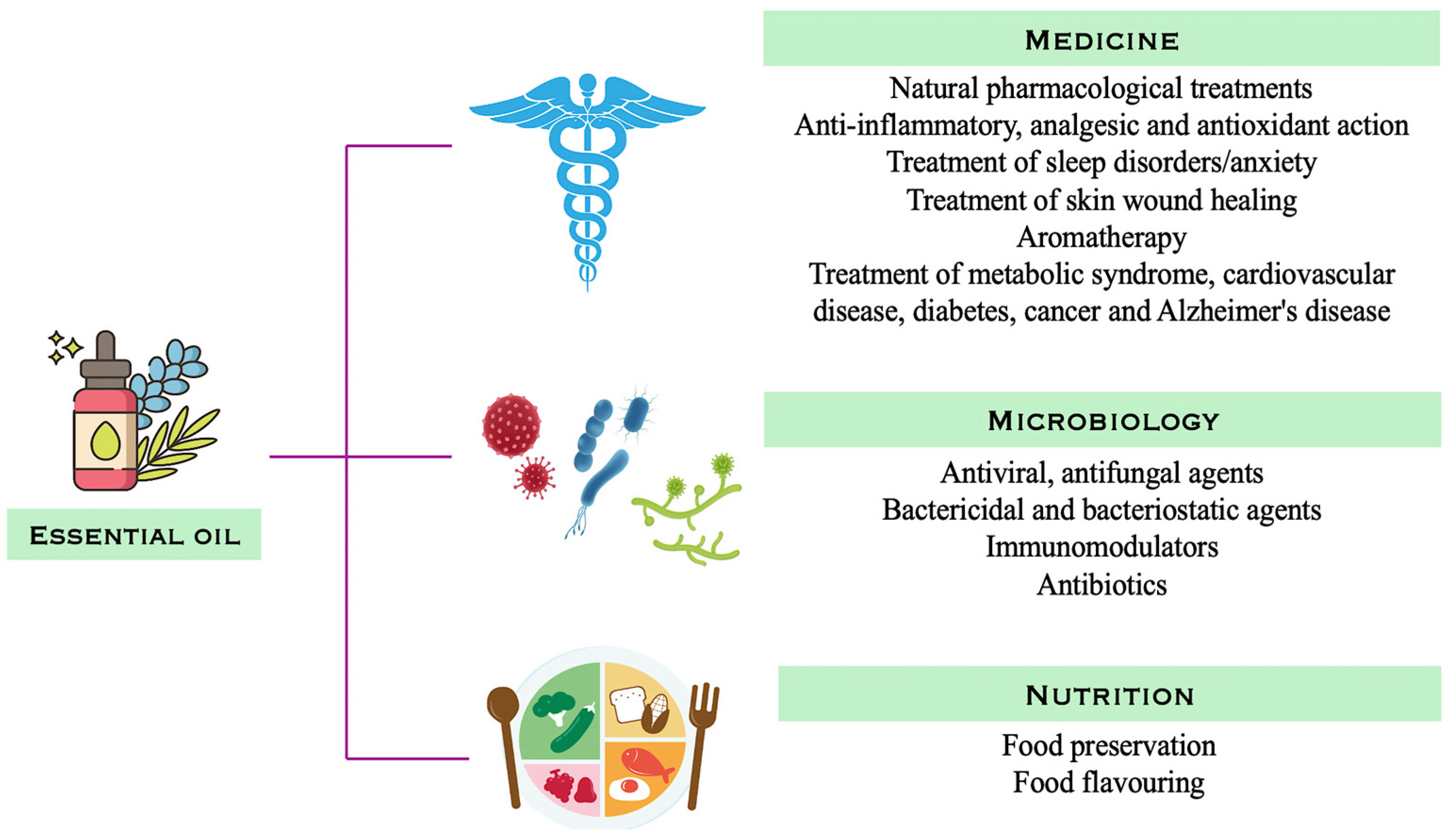

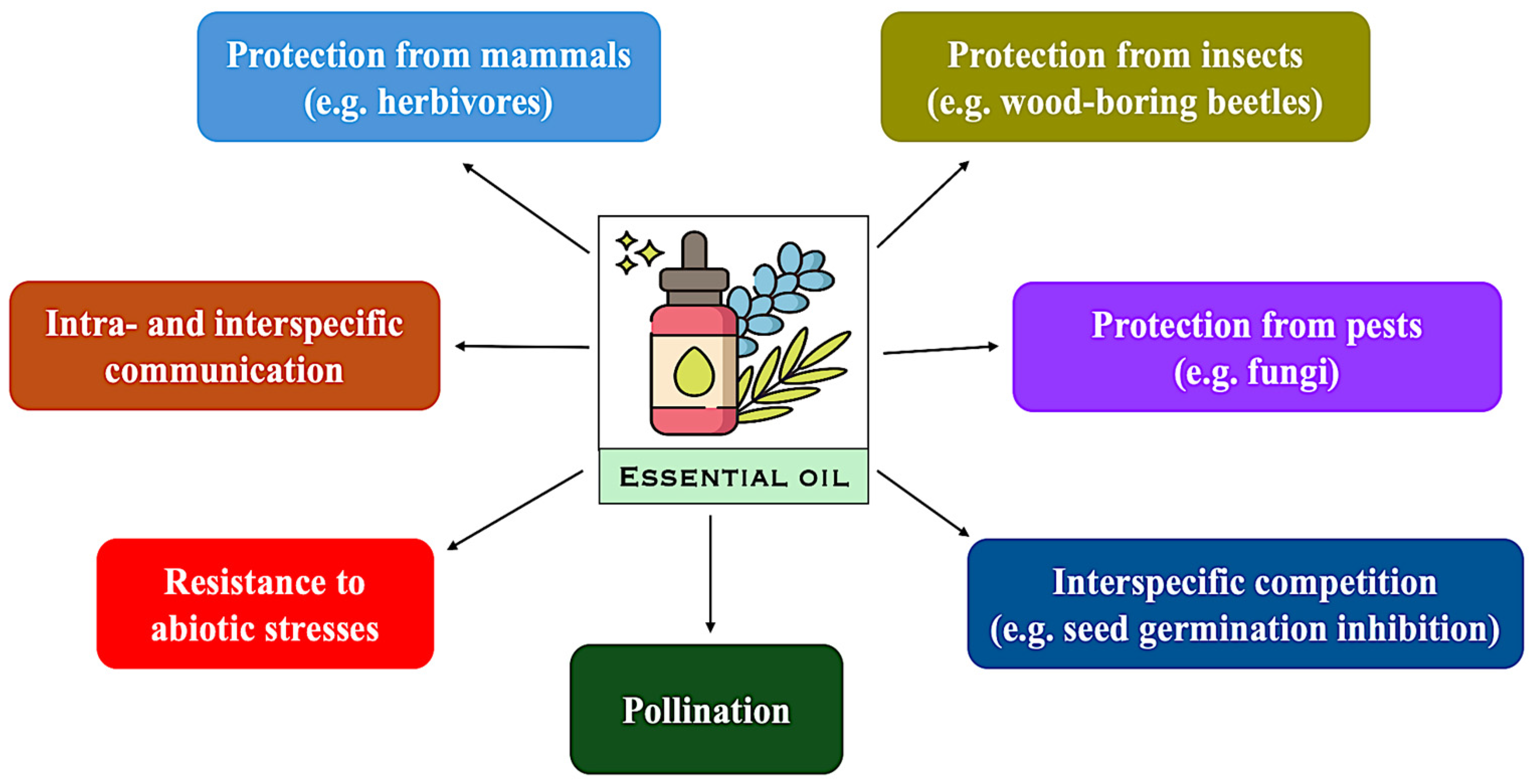

2. Essential Oils and Their Roles in Plant Protection

3. Methodology

4. Essential Oils and Abiotic Stress

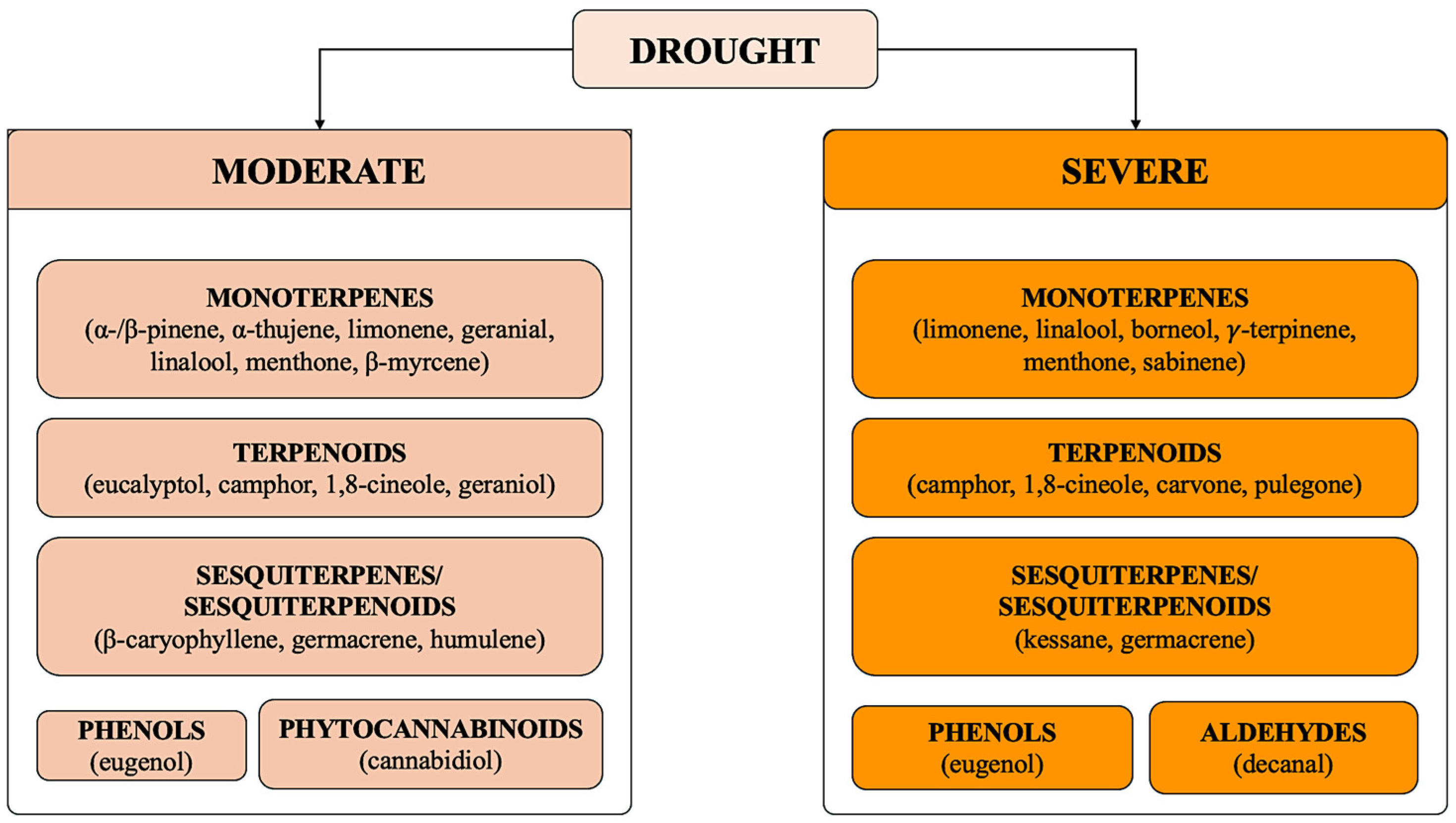

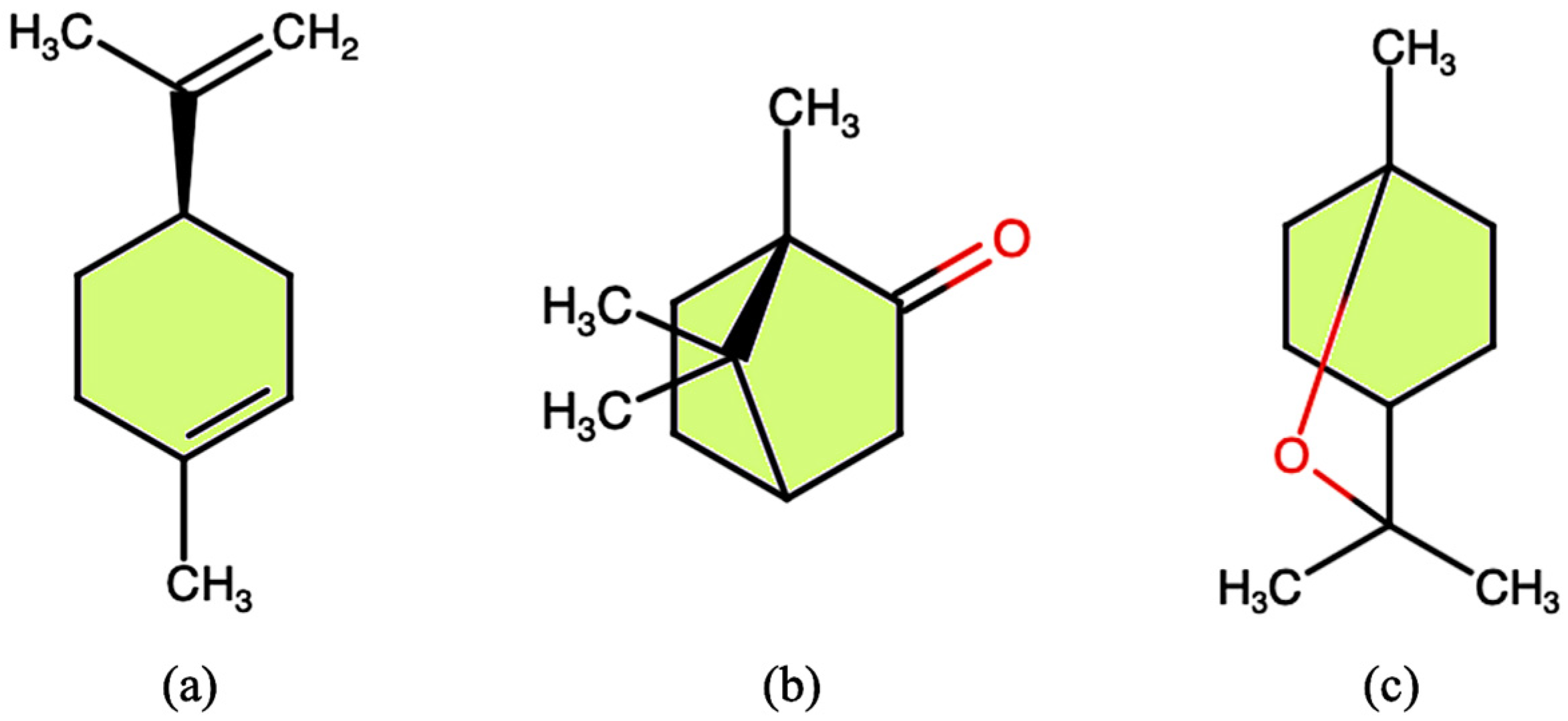

4.1. Drought Stress

| Plant Species | Experimental Conditions | Plant Organ Tested | Effect on the Synthesis and Composition of EO | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Greenhouse | Leaves | Increase under stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning α-pinene and eucalyptol. | [41] |

| Thymus daenensis Celak | Greenhouse. Foliar application with chitosan. | Leaves and flowers | Increase under mild stress in CTRLs. Increase under mild and severe stress in chitosan-treated plants. | [25] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Botanical garden | Leaves, flowers, and fruits | Increase under moderate stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning camphor, α-thujene, and α-pinene. | [42] |

| Mentha piperita L. Salvia lavandulifolia Vahl. Salvia sclarea L. Thymus capitatus L. Thymus mastichina L. Lavandula latifolia Med. | Field experiment | Plant shoots | Decrease under stress only in L. latifolia and S. sclarea. No change was observed in other species. | [27] |

| Mentha spicata L. | Field experiment | Leaves | Decrease under severe stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning carvone, limonene, and 1,8-cineole. | [43] |

| Salvia nemorosa L. Salvia reuterana Boiss | Greenhouse. Foliar application with melatonin. | Flowering stems | Increase under moderate stress in CTRLs. Increase under moderate stress in melatonin-treated plants. Changes in chemical composition concerning β-caryophyllene and germacrene-B in S. nemorosa. Changes in chemical composition concerning (E)-β-ocimene, germacrene-D, and α-gurjunene in S. reuterana. | [44] |

| Ocimum tenuiflorum L. | Growth chamber | Leaves | Increase under stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning eugenol and methyl eugenol. | [45] |

| Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Lavandula stricta Del. | Pots experiment | Plant shoots | Increase under moderate stress in L. angustifolia. Increase under severe stress in L. stricta. Changes in chemical composition concerning bornyl formate, caryophyllene oxide and linalool, and camphor in L. angustifolia. Changes in chemical composition concerning linalool, decanal, 1-decanol, and kessane in L. stricta. | [46] |

| Salvia officinalis L. | Greenhouse | Leaves | Increase under moderate stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineole, α-thujone, and camphor. | [28] |

| Citrus × latifolia Tanaka Citrus aurantifolia (Christ.) Swingle | Greenhouse. Foliar application with melatonin. | Leaves | Increase under moderate and severe stress in CTRLs. Increase under moderate and severe stress in melatonin-treated plants. Changes in chemical composition concerning limonene and γ-terpinene in C. aurantifolia. Changes in chemical composition concerning β-pinene, sabinene, limonene, and γ-terpinene in C. latifolia. | [47] |

| Mentha piperita L. | Growth chamber. Bacterial inoculation with Pseudomonas simiae WCS417r and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens GB03. | Plant shoots | Increase under moderate and severe stress only in CTRLs. Changes in chemical composition concerning menthone and pulegone only in CTRLs. | [29] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. Ocimum × africanum Lour. Ocimum americanum L. | Greenhouse | Leaves and flowers | Decrease under severe stress in O. basilicum and O. americanum. No change was observed in O. x africanum. Drought altered the entire chemical composition of the EOs extracted from the three species. | [30] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Growth chamber | Plant shoots | Slight increase under moderate and severe stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning eugenol and germacrene. | [48] |

| Coriandrum sativum L. | Field experiment | Seeds | Increase under stress. | [49] |

| Lavandula angustifolia Mill. | Greenhouse | Leaves and flowers | Increase under severe stress. Changes in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineol, camphor, and borneol. | [31] |

| Thymus × citriodorus | Greenhouse | Plant shoots | Decrease under stress. Change in chemical composition concerning neral, geraniol, and geranial. | [50] |

| Thymus vulgaris L. | Greenhouse. Foliar application with kaolin. | Plant shoots | Increase under moderate and severe stress in CTRLs. Increase under moderate and severe stress in kaolin-treated plants. | [51] |

| Cannabis sativa L. | Greenhouse. Foliar application with nanosilicon particles. | Inflorescences (floral bracts) | Increase under moderate stress in CTRLs. Increase under moderate stress in nanosilicon-treated plants. Change in chemical composition concerning limonene, caryophyllene, β-myrcene, β-ocimene, humulene, and cannabidiol. | [52] |

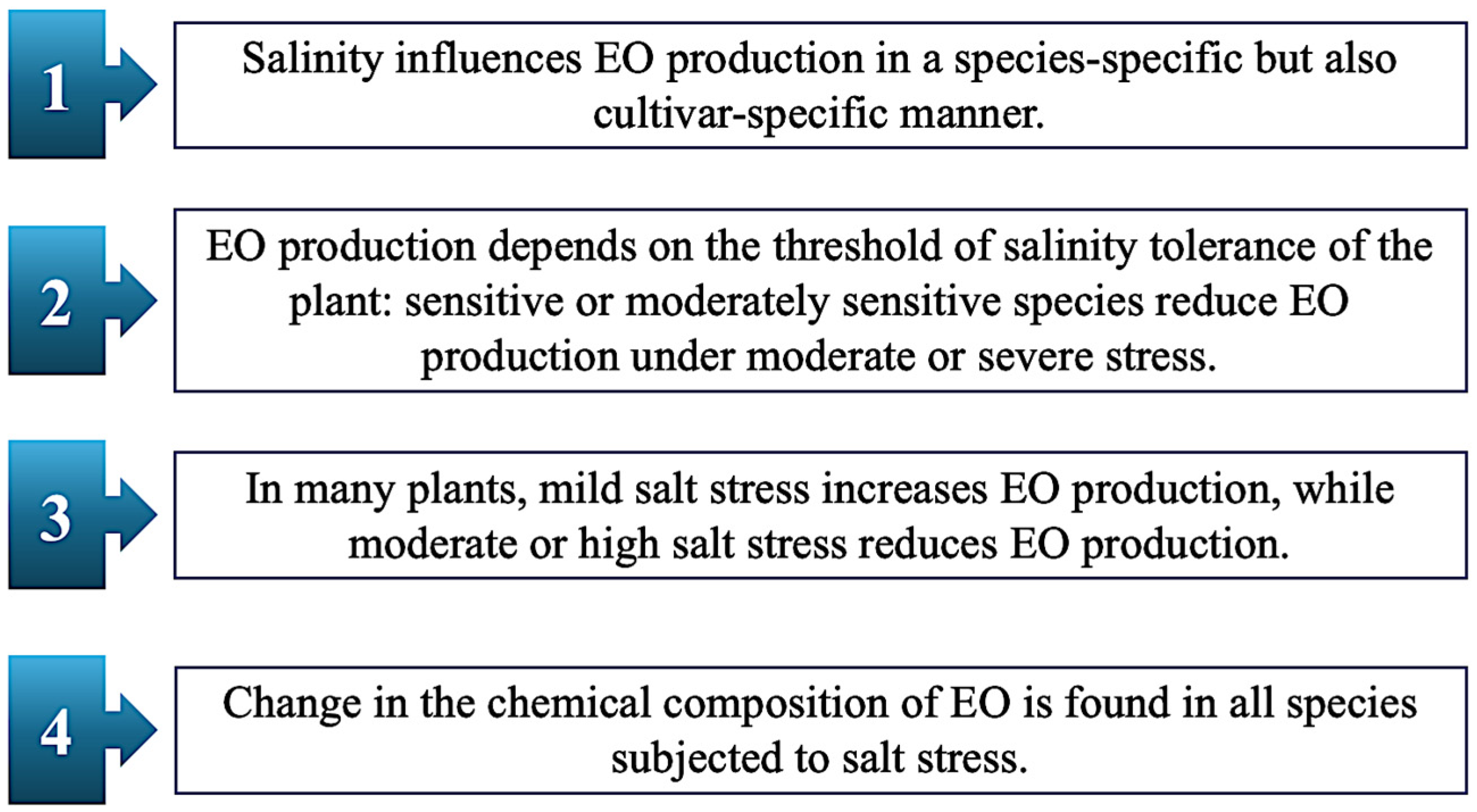

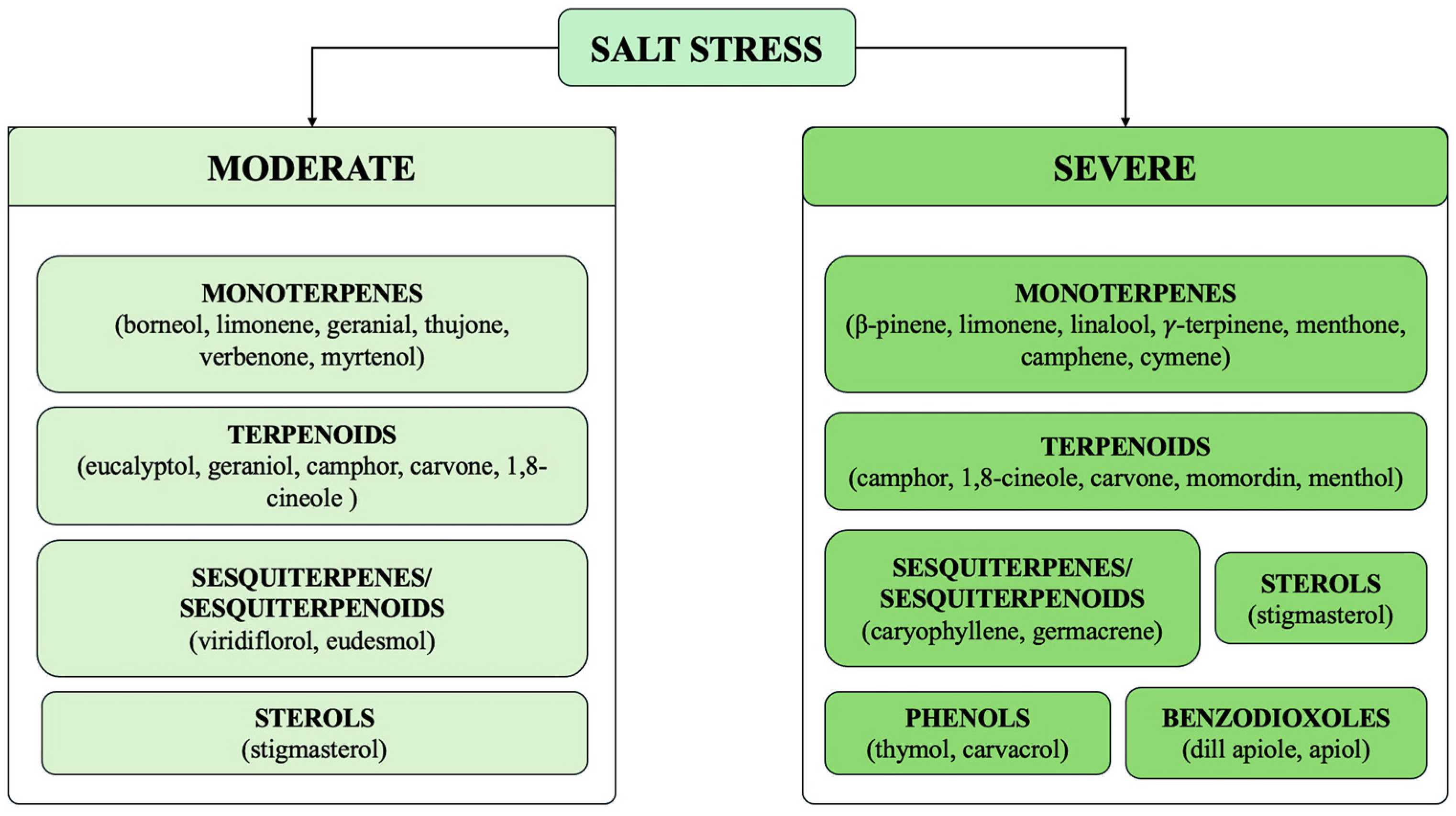

4.2. Salt Stress

| Plant Species | Experimental Conditions | Plant Organ Tested | Effect on the Synthesis and Composition of EO | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salvia officinalis L. | Greenhouse | Leaves | Salt stress did not induce the synthesis of new oils. Change in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineol, β-thujone, camphor, borneol and viridiflorol. | [63] |

| Cuminum cyminum L. | Hydroponically cultivated in a saline solution | Seeds | Decrease under severe stress. Change in chemical composition concerning β-pinene, 1-phenyl-1,2 ethanediol, and camphor. | [70] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Greenhouse. Foliar application with salicylic acid. | Leaves | Decrease under stress in CTRLs. Decrease under severe stress in salicylic acid-treated plants. Change in chemical composition concerning cineole, camphor, borneol and verbenone in CTRLs. Change in chemical composition concerning verbenone and caryophyllene oxide in treated plants. | [71] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Field trials. | Plant shoots | Decrease under stress. Change in chemical composition concerning α-pinene, eucalyptol, camphene, borneol, D-verbenone, bornyl acetate, carcyophyllene and caryophyllene oxide. | [72] |

| Dracocephalum moldavica L. | Greenhouse. Treatment with TiO2 NPs, solubilized in irrigation solution. | Plant shoots | Increase synthesis under moderate and severe stress in CTRLs. Decrease under stress in treated plants. Change in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineole, myrtenol, nerol, and β-eudesmol in CTRLs. Change in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineole, myrtenol, germacrene and linalool in treated plants. | [73] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Greenhouse. Plants were treated with silicon, used as a foliar spray or soil additive. | Plant shoots | Increase synthesis under stress in CTRLs. Increase synthesis in all plants treated with silicon. | [58] |

| Momordica charantia L. | Growth chamber. Foliar application with Cs-Se NPs. | Fruits | Increase synthesis under moderate and severe stress in both CTRLs and Cs-Se NPs treated plants. Change in chemical composition concerning gentisic acid, stigmasterol, and momordin, in CTRLs and treated plants. | [62] |

| Mentha piperita L. | Greenhouse. Inoculation with Piriformospora indica, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, and co-inoculation with P. indica and fungi. | Leaves | Decrease in synthesis under moderate and severe stress in both CTRLs and inoculated plants. Change in chemical composition concerning menthol, menthone, and limonene. | [56] |

| Anethum graveolens L. | Greenhouse. Foliar application with GA3, SA, and CK. | Seeds | Decrease in synthesis under severe stress in both CTRLs and treated seeds. Change in chemical composition concerning dihydrocarvone, limonene, and dillapiole. | [74] |

| Anethum graveolens L. | Greenhouse. Biochar-based nanocomposites were added to soil. | Seeds | Increase synthesis under severe stress. Change in chemical composition concerning limonene, carvone, apiol, and dillapiole. | [75] |

| Aloysia citrodora Paláu (Lippia citriodora Kunth) | Greenhouse. Foliar application with Se and N-Se. | Leaves | Increase EO% under moderate and severe stress in both CTRLs and treated plants. | [76] |

| Origanum vulgare L. | Greenhouse | Plant shoots | Decrease in synthesis under severe stress in O. vulgare subsp. vulgare and gracile. Increase at low salt stress only in the subsp. gracile. Change in chemical composition concerning carvacrol, thymol, terpinene, and cymene. | [59] |

| Mentha longifolia (L.) Huds. | Greenhouse | Plant shoots | Decrease synthesis under moderate and severe stress. Change in chemical composition concerning limonene and carvone. | [60] |

| Mentha spicata L. Origanum dictamnus L. Origanum onites L. | Greenhouse | Plant shoots | No change was observed in M. spicata. Increase under stress in O. onites. Decrease under stress in O. dictamnus. Change in chemical composition concerning limonene, carvone, 1,8-cineole, and β-caryophyllene in M. spicata. Change in chemical composition concerning cymene and carvacrol in O. dictamus. Change in chemical composition concerning carvacrol and linalool in O. onites. | [34] |

| Salvia abrotanoides (Kar.) Sytsma Salvia yangii B.T. Drew | Field experiment | Plant shoots | Decrease under moderate or severe stress in cv. PAtKH, PAbKH, and PAbAD. Increase under moderate or severe stress in PAbSM and PAbAY. Change in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineole, camphor, and borneol. | [77] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Greenhouse. Plants treatment involved foliar application with Thymbra spicata extract and inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhiza. | Plant shoots | Decrease under severe stress in CTRLs. Slight increase under moderate stress e decrease under severe stress in treated plants. Change in chemical composition concerning 1,8-cineole, camphene and geranyl acetate. | [55] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Pots experiment | Plant shoots | Increase under severe stress (except in the cultivar Dark opal). | [57] |

| Thymus × citriodorus | Greenhouse | Plant shoots | Decrease under stress. Change in chemical composition concerning geraniol, geranial, and neral. | [50] |

5. Future Perspective of EOs Application in Agriculture

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| APX | Ascorbate Peroxidase |

| bHLH | Basic Helix-Loop-Helix transcription factors |

| CAT | Catalase |

| Chl | Chlorophyll |

| CK | Cytokinin |

| Cs–Se NP | Chitosan–Selenium Nanoparticle |

| CTRL | Control |

| DXR | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase |

| DXS | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase |

| EOs | Essential Oils |

| Eto | Evapotranspiration Demand |

| FPPS | Farnesyl Diphosphate Synthase |

| FW | Fresh Weight |

| GA3 | Gibberellic Acid |

| GPPS | Geranyl Diphosphate Synthase |

| HMGR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MEP | 2-C-Methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate |

| MSI | Membrane Stability Index |

| MVA | Mevalonate Pathway |

| MVK | Mevalonate Kinase |

| MYB | Myeloblastosis-related transcription factors |

| N-Se | Nano-Selenium |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| PPO | Polyphenol Oxidase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RWC | Relative Water Content |

| SA | Salicylic Acid |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| STI | Salt Tolerance Index |

| SVI | Seed Vigor Index |

| TiO2 NPs | Titanium dioxide Nanoparticles |

| TLA | Total Leaf Area |

| TPS | Terpene Synthase |

References

- Ben Miri, Y. Essential oils: Chemical composition and diverse biological activities: A comprehensive review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquila, P.; Sena, G.; Crudo, M.; Passarino, G.; Bellizzi, D. Effect of essential oils of Apiaceae, Lamiaceae, Lauraceae, Myrtaceae, and Rutaceae family plants on growth, biofilm formation, and quorum sensing in Chromobacterium violaceum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus faecalis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadu, M.G.; Trong Le, N.; Viet Ho, D.; Quoc Doan, T.; Tuan Le, A.; Raal, A.; Usai, M.; Marchetti, M.; Sanna, G.; Madeddu, S.; et al. Phytochemical compositions and biological activities of essential oils from the leaves, rhizomes and whole plant of Hornstedtia bella Škorničk. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Sureda, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Daglia, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Valussi, M.; Tundis, R.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; et al. Biological activities of essential oils: From plant chemoecology to traditional healing systems. Molecules 2017, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.Y.; Li, J.; Yin, H.M.; He, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, T. Stabilization of essential oil: Polysaccharide-based drug delivery system with plant-like structure based on biomimetic concept. Polymers 2023, 15, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, X.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Z.; Yun, Y.; Xie, M.; Chen, L. Combination of plant essential oils and ice: Extraction, encapsulation and applications in food preservation. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, I.K.; Salih, S.J. Extraction of essential oils from citrus by-products using microwave steam distillation. Iraqi J. Chem. Peteroleum Eng. 2015, 16, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Song, R.; Zhang, M.; Li, X. Research progress on extraction, separation, and purification methods of plant essential oils. Separations 2023, 10, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Chemical diversity, yield, and quality of aromatic plants. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugreet, B.S.; Suroowan, S.; Rengasamy, R.R.K.; Mahomoodally, M.F. Chemistry, bioactivities, mode of action and industrial applications of essential oils. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 101, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyita, A.; Mustika Sari, R.; Dwi Astuti, A.; Yasir, B.; Rahma Rumata, N.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and terpenoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservatives. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chi, P.; Liu, H.; Jing, Z.; Cao, H.; Du, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Essential oils: Chemical constituents, potential neuropharmacological effects and aromatherapy—A review. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 6, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential oils: Chemistry and pharmacological activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, S.; Tuteja, N. Cold, salinity and drought stresses: An overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 444, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa Gonçalves, D.; Rodrigues Ribeiro, W.; Gonçalves, D.C.; Menini, L.; Costa, H. Recent advances and future perspective of essential oils in control Colletotrichum spp.: A sustainable alternative in postharvest treatment of fruits. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzali, L.; Allagui, M.B.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Molina-Hernandez, J.B.; Moumni, M.; Mezzalama, M.; Romanazzi, G. Basic Substances and potential basic substances: Key compounds for a sustainable management of seedborne pathogens. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, C.; Lamont, B.B. Plant tannins and essential oils have an additive deterrent effect on diet choice by kangaroos. Forests 2021, 12, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaza, V.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Antibacterial activity of selected essential oil components and their derivatives: A review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.B.; Wilson, T.M.; Wilson, J.S.; Ruggles, Z.; Topham Wilson, L.; Packer, C.; Young, J.G.; Bowerbank, C.R.; Carlson, R.E. Pollination and essential oil production of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. (Lamiaceae). Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Oliveira, C.d.; Gouvêa-Silva, J.G.; Brito Machado, D.d.; Felisberto, J.R.S.; Queiroz, G.A.d.; Guimarães, E.F.; Ramos, Y.J.; Moreira, D.d.L. Chemical diversity and redox values change as a function of temporal variations of the essential oil of a tropical forest shrub. Diversity 2023, 15, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, C.; Duca, D.; Glick, B.R. Mechanisms of plant response to salt and drought stress and their alteration by rhizobacteria. Plant Soil 2017, 410, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansinhos, I.; Gonçalves, S.; Romano, A. How climate change-related abiotic factors affect the production of industrial valuable compounds in Lamiaceae plant species: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1370810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avasiloaiei, D.I.; Calara, M.; Brezeanu, P.M.; Murariu, O.C.; Brezeanu, C. On the future perspectives of some medicinal plants within Lamiaceae botanic family regarding their comprehensive properties and resistance against biotic and abiotic stresses. Genes 2023, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aishwath, O.P.; Lal, R. Resilience of spices, medicinal and aromatic plants with climate change induced abiotic stresses. Ann. Plant Soil Res. 2016, 18, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bistgani, Z.E.; Siadat, S.A.; Bakhshandeh, A.; Pirbalouti, A.G.; Hashemi, M. Interactive effects of drought stress and chitosan application on physiological characteristics and essential oil yield of Thymus daenensis Celak. Crop J. 2017, 5, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, M.; Kuiry, R.; Pal, P.K. Understanding the consequence of environmental stress for accumulation of secondary metabolites in medicinal and aromatic plants. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2020, 18, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Caparrós, P.; Romero, M.J.; Llanderal, A.; Cermeño, P.; Lao, M.T.; Segura, M.L. Effects of drought stress on biomass, essential oil content, nutritional parameters, and costs of production in six Lamiaceae species. Water 2019, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanbeigi, A.; Yıldız, M.; Dıraman, H.; Terzi, H.; Sakartepe, E.; Yıldız, E. Growth responses and essential oil profile of Salvia officinalis L. influenced by water deficit and various nutrient sources in the greenhouse. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 7327–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappero, J.; Cappellari, L.d.R.; Palermo, T.B.; Giordano, W.; Banchio, E. Influence of drought stress and PGPR inoculation on essential oil yield and volatile organic compound emissions in Mentha piperita. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, S.M.; Radácsi, P. Influence of drought stress on growth and essential oil yield of Ocimum species. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, R.; Heidari, M. Impact of drought stress on biochemical and molecular responses in lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.): Effects on essential oil composition and antibacterial activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1506660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Sangwan, N.; Abad Farooqi, A.; Sangwan, R.S. Effect of drought stress on growth and essential oil metabolism in lemongrasses. New Phytol. 1994, 128, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, I.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Pedro, L.G.; Sousa, M.J. Composition variation of the essential oil from Ocimum basilicum L. cv. Genovese Gigante in response to Glomus intraradices and mild water stress at different stages of growth. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 90, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, M.K.; Giannakoula, A.E.; Ouzounidou, G.; Papaioannou, C.; Lianopoulou, V.; Philotheou-Panou, E. The effect of salinity and drought on the essential oil yield and quality of various plant species of the Lamiaceae family (Mentha spicata L., Origanum dictamnus L., Origanum onites L.). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistgani, Z.E.; Barker, A.V.; Hashemi, M. Physiology of medicinal and aromatic plants under drought stress. Crop J. 2024, 12, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzilday, B.; Takahashi, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Uzilday, R.O.; Fujii, N.; Takahashi, H.; Turkan, I. Role of abscisic acid, reactive oxygen species, and Ca2+ signaling in hydrotropism-drought avoidance-associated response of roots. Plants 2024, 13, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraj, T.A.; Fu, J.; Raza, M.A.; Zhu, C.; Shen, Q.; Xu, D.; Wang, Q. Transcriptional factors regulate plant stress responses through mediating secondary metabolism. Genes 2020, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Yang, S.; Wang, D.; Qin, F.; Wang, S.; Meng, S. Advances in the biosynthesis of plant terpenoids: Models, mechanisms, and applications. Plants 2025, 14, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, X.; Qian, Y.; Mao, B. Metabolic profiling of terpene diversity and the response of prenylsynthase-terpene synthase genes during biotic and abiotic stresses in Dendrobium catenatum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoso, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Ritonga, F.N.; Ali, Q.; Channa, M.M.; Alshegaihi, R.M.; Meng, Q.; Ali, M.; Zaman, W.; Brohi, R.D.; et al. WRKY Transcription factors (TFs): Molecular switches to regulate drought, temperature, and salinity stresses in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1039329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, T.B.; Pereira, N.N.D.J.; Silva, J.C.R.L.; Fonseca, F.S.A.D.; Martins, E.R. Influence of water regime on initial growth and essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus. Ciênc. Rural 2017, 47, e20150530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidgoli, R.D. Effect of drought stress on some morphological characteristics, quantity and quality of essential oil in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.). Adv. Med. Plant Res. 2018, 6, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, S.; Ahmad, U.; Ferreira, M.I.; Alvino, A. Evaluation of the effect of irrigation on biometric growth, physiological response, and essential oil of Mentha spicata (L.). Water 2019, 11, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidabadi, S.S.; VanderWeide, J.; Sabbatini, P. Exogenous melatonin improves glutathione content, redox state and increases essential oil production in two Salvia species under drought stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.T.T.; Nguyen, N.H.; Choi, W.S.; Lee, J.H.; Cheong, J.-J. Biosynthesis of essential oil compounds in Ocimum tenuiflorum is induced by abiotic stresses. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2020, 156, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgini Shabankareh, H.; Khorasaninejad, S.; Soltanloo, H.; Shariati, V. Physiological response and secondary metabolites of three lavender genotypes under water deficit. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Shahsavar, A. The effect of foliar application of melatonin on changes in secondary metabolite contents in two citrus species under drought stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 692735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, B.; Petek, M.; Vidak, M.; Šatović, Z.; Gunjača, J.; Politeo, O.; Carović-Stanko, K. Effect of drought and salinity stresses on nutrient and essential oil composition in Ocimum basilicum L. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2023, 88, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.N.; Mittal, G.K.; Singh, B.; Manohar, P.; Mahatma, M.K. Water deficit stress condition alters stress metabolites and essential oil content of coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.). Int. J. Seed Spice 2024, 14, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, E.; Beáta, G.; Zsuzsanna, P. Essential oils under stress: How drought and salinity shape the physiological and biochemical profile of Thymus × citriodorus. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, E.; Aghamir, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Eghlima, G. Kaolin application improved growth performances, essential oil percentage, and phenolic compound of Thymus vulgaris L. under drought stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezghiyan, A.; Esmaeili, H.; Farzaneh, M. Nanosilicon application changes the morphological attributes and essential oil compositions of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) under water deficit stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borromeo, I.; Domenici, F.; Del Gallo, M.; Forni, C. Role of polyamines in the response to salt stress of tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borromeo, I.; Domenici, F.; Giordani, C.; Del Gallo, M.; Forni, C. Enhancing bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) resilience: Unveiling the role of halopriming against saltwater stress. Seeds 2024, 3, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solgi, M.; Bagnazari, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Azizi, A. Thymbra spicata extract and arbuscular mycorrhizae improved the morphophysiological traits, biochemical properties, and essential oil content and composition of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) under salinity stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalvandi, M.; Amerian, M.; Pirdashti, H.; Keramati, S. Does co-inoculation of mycorrhiza and Piriformospora indica fungi enhance the efficiency of chlorophyll fluorescence and essential oil composition in peppermint under irrigation with saline water from the Caspian Sea? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftahizadeh, M.; Shahhoseini, R.; Ghanbari, F. Biochemical, physiological and phenotypic variation in Ocimum Basilicum L. cultivars under salt stress conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.; Elhindi, K.M.; Alotaibi, M.A. Silicon supplementation mitigates salinity stress on Ocimum basilicum L. via improving water balance, ion homeostasis, and antioxidant defense system. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimzadeh, Z.; Hassani, A.; Mandoulakani, B.A.; Sepehr, E.; Morshedloo, M.R. Intraspecific divergence in essential oil content, composition and genes expression patterns of monoterpene synthesis in Origanum vulgare subsp. vulgare and subsp. gracile under salinity stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Ahmed, S.; Luxmi, S.; Rai, G.; Gupta, A.P.; Bhanwaria, R.; Gandhi, S.G. An assessment of the physicochemical characteristics and essential oil composition of Mentha longifolia (L.) Huds. exposed to different salt stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1165687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brengi, S.H.; Moubarak, M.; El-Naggar, H.M.; Osman, A.R. Promoting salt tolerance, growth, and phytochemical responses in coriander (Coriandrum sativum L. cv. Balady) via eco-friendly Bacillus subtilis and cobalt. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikhalipour, M.; Esmaielpour, B.; Behnamian, M.; Gohari, G.; Giglou, M.T.; Vachova, P.; Rastogi, A.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M. Chitosan-selenium nanoparticle (Cs-Se NP) foliar spray alleviates salt stress in bitter melon. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tounekti, T.; Khemira, H. NaCl stress-induced changes in the essential oil quality and abietane diterpene yield and composition in common sage. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 4, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahl, S.A.; Omer, E.A. Medicinal and aromatic plants production under salt stress. A review. Herba Pol. 2011, 57, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizaz, M.; Lubna; Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Bilal, S.; Kim, K.-M.; AL-Harrasi, A. Regulatory dynamics of plant hormones and transcription factors under salt stress. Biology 2024, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Hanif, M.A.; Mushtaq, Z.; Al-Sadi, A.M. Biosynthesis of essential oils in aromatic plants: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2016, 32, 117–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmar, D.; Kleinwächter, M. Stress enhances the synthesis of secondary plant products: The impact of stress-related over-reduction on the accumulation of natural products. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebey, I.B.; Bourgou, S.; Rahali, F.Z.; Msaada, K.; Ksouri, R.; Marzouk, B. Relation between salt tolerance and biochemical changes in cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) seeds. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Esawi, M.A.; Elansary, H.O.; El-Shanhorey, N.A.; Abdel-Hamid, A.M.E.; Ali, H.M.; Elshikh, M.S. Salicylic acid-regulated antioxidant mechanisms and gene expression enhance rosemary performance under saline conditions. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmoum, R.; Haid, S.; Biche, M.; Djazouli, Z.; Zebib, B.; Merah, O. Effect of salinity and water stress on the essential oil components of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.). Agronomy 2019, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohari, G.; Mohammadi, A.; Akbari, A.; Panahirad, S.; Dadpour, M.R.; Fotopoulos, V.; Kimura, S. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) promote growth and ameliorate salinity stress effects on essential oil profile and biochemical attributes of Dracocephalum moldavica. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi-Golezani, K.; Nikpour-Rashidabad, N.; Samea-Andabjadid, S. Application of growth promoting hormones alters the composition and antioxidant potential of dill essential oil under salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi-Golezani, K.; Rahimzadeh, S. The biochar-based nanocomposites influence the quantity, quality and antioxidant activity of essential oil in dill seeds under salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, F.; Bag-Nazari, M.; Azizi, A. Exogenous application of selenium and nano-selenium alleviates salt stress and improves secondary metabolites in lemon verbena under salinity stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, Z.; Rahimmalek, M.; Sabzalian, M.R.; Arzani, A.; Kiani, R.; Gharibi, S.; Wróblewska, K.; Szumny, A. Chemical composition, physiological and morphological variations in Salvia subg. Perovskia populations in response to different salinity levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, P.F.; Cassa, N.; de Melo, A.S.; Dantas Neto, J.; Meneghetti, L.A.M.; Custódio, A.S.C.; de Oliveira, N.P.R.; da Silva, T.J.A.; Bonfim-Silva, E.M.; Andrade, S.P.; et al. Advances in crop genetic improvement to overcome drought stress: Bibliometric and meta-analysis. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jabeur, M.; Kthiri, Z.; Djébali, N.; Karmous, C.; Hamada, W. A case study of seed biopriming and chemical priming: Seed coating with two types of bioactive compounds improves the physiological state of germinating seeds in durum wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 2022, 51, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubenova, A.; Nikolova, M.; Slavov, S.B. Inhibitory Effect of greek oregano extracts, fractions and essential oil on economically important plant pathogens on soybean. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 15, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazeer, H.; Shridhar Gaonkar, S.; Doria, E.; Pagano, A.; Balestrazzi, A.; Macovei, A. Plant-based biostimulants for seeds in the context of circular economy and sustainability. Plants 2024, 13, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, G.; Thakur, S.; Shandilya, M.; Sharma, S.; Thakur, S.; Kalia, S. Nanotechnology for sustainable agro-food systems: The need and role of nanoparticles in protecting plants and improving crop productivity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 194, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, J.P.; Nasser, V.G.; Macedo, W.R.; Santos, M.F.C.; Silva, G.H. The biostimulant potential of clove essential oil for treating soybean seeds. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, R.; Franzoni, G.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants application in horticultural crops under abiotic stress conditions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parađiković, N.; Teklić, T.; Zeljković, S.; Lisjak, M.; Špoljarević, M. Biostimulants research in some horticultural plant species—A review. Food Energy Secur. 2019, 8, e00162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavallieratos, N.G.; Eleftheriadou, N.; Filintas, C.S.; Boukouvala, M.C.; Gidari, D.L.S.; Skourti, A.; Ntinokas, D.; Ferrati, M.; Spinozzi, E.; Petrelli, R.; et al. The potency of essential oils in combating stored-product pests: From nature to nemesis. Plants 2025, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares-Sierra, A.; Monsonís-Güell, E.; Gómez, C.; Abril, S.; Moreno-Gómez, M. Essential oils as bioinsecticides against Blattella germanica (Linnaeus, 1767): Evaluating its efficacy under a practical framework. Insects 2025, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Chemical composition of essential oils and their potential applications in postharvest storage of cereal grains. Molecules 2025, 30, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavallieratos, N.G.; Boukouvala, M.C.; Skourti, A.; Filintas, C.S.; Eleftheriadou, N.; Gidari, D.L.S.; Spinozzi, E.; Ferrati, M.; Petrelli, R.; Cianfaglione, K.; et al. Essential oils from three Cupressaceae species as stored wheat protectants: Will they kill different developmental stages of nine noxious arthropods? J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 105, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyotsna, B.; Patil, S.; Prakash, Y.S.; Rathnagiri, P.; Kishor, P.K.; Jalaja, N. Essential oils from plant resources as potent insecticides and repellents: Current status and future perspectives. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 61, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğuz, M.Ç.; Oğuz, E.; Güler, M. Seed priming with essential oils for sustainable wheat agriculture in semi-arid region. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Afzal, I.; Shabbir, R.; Ikram, K.; Zaheer, M.S.; Faheem, M.; Ali, H.H.; Iqbal, J. Seed coating technology: An innovative and sustainable approach for improving seed quality and crop performance. J. Saudi Soc. Agri. Sci. 2022, 21, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalija, E.; Pustahija, F.; Parić, A. Effect of priming with silver fir and oregano essential oils on seed germination and vigour of Silene sendtneri. Rad. Šumarskog Fak. Univ. Sarajev. 2020, 50, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, E.; Herzyk, P.; Perrella, G.; Colot, V.; Amtmann, A. Hyperosmotic priming of Arabidopsis seedlings establishes a long-term somatic memory accompanied by specific changes of the epigenome. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambona, C.M.; Koua, P.A.; Léon, J.; Ballvora, A. Stress memory and its regulation in plants experiencing recurrent drought conditions. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 26, Erratum in Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-023-04338-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudani, S.; Poza-Carrión, C.; De la Cruz Gómez, N.; González-Coloma, A.; Andrés, M.F.; Berrocal-Lobo, M. Essential oils prime epigenetic and metabolomic changes in tomato defense against Fusarium oxysporum. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 804104, Erratum in Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1443732. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1443732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Aragonés, J.; Terrab, A.; Balao, F. Plant volatile organic compounds evolution: Transcriptional regulation, epigenetics and polyploidy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquila, P.; Paparazzo, E.; Crudo, M.; Bonacci, S.; Procopio, A.; Passarino, G.; Bellizzi, D. Antibacterial activity and epigenetic remodeling of essential oils from calabrian aromatic plants. Nutrients 2022, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Saad, R.; Ben Romdhane, W.; Wiszniewska, A.; Baazaoui, N.; Taieb Bouteraa, M.; Chouaibi, Y.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Kačániová, M.; Čmiková, N.; Ben Hsouna, A.; et al. Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil enhances salt stress tolerance of durum wheat seedlings through ROS detoxification and stimulation of antioxidant defense. Protoplasma 2024, 261, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Jabeur, M.; Vicente, R.; López-Cristoffanini, C.; Alesami, N.; Djébali, N.; Gracia-Romero, A.; Serret, M.D.; López-Carbonell, M.; Araus, J.L.; Hamada, W. A novel aspect of essential oils: Coating seeds with thyme essential oil induces drought resistance in wheat. Plants 2019, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borromeo, I.; De Luca, A.; Domenici, F.; Giordani, C.; Rossi, L.; Forni, C. Antioxidant properties of Lippia alba essential oil: A potential treatment for oxidative stress-related conditions in plants and cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borromeo, I.; Giordani, C.; Forni, C. Efficacy of Lippia alba essential oil in alleviating osmotic and oxidative stress in salt-affected bean plants. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hefny, M.; Hussien, M.K. Enhancing the growth and essential oil components of Lavandula latifolia using Malva parviflora extract and humic acid as biostimulants in a field experiment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Et-Tazy, L.; Desideri, S.; Fedeli, R.; Lamiri, A.; Loppi, S. Unlocking biostimulant potential of essential oils to improve chickpea germination and nutritional quality. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2025, 159, 1667–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.A.; Mohammed, D.M.; Abd El Gawad, F.; Orabi, M.A.; Gupta, R.K.; Srivastav, P.P. Valorization of food processing waste byproducts for essential oil production and their application in food system. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Fiorani, F.; Pieruschka, R.; Wojciechowski, T.; van der Putten, W.H.; Kleyer, M.; Schurr, U.; Postma, J. Pampered inside, pestered outside? Differences and similarities between plants growing in controlled conditions and in the field. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 838–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proto, M.R.; Biondi, E.; Baldo, D.; Levoni, M.; Filippini, G.; Modesto, M.; Di Vito, M.; Bugli, F.; Ratti, C.; Minardi, P.; et al. Es-sential oils and hydrolates: Potential tools for defense against bacterial plant pathogens. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Aim of the work | To collect relevant and recent literature, exploring the relationship between EOs and plants under abiotic stress conditions. |

| Keywords used | essential oils, climate change, abiotic stresses, salt stress, drought stress, soil salinity, and plant protection. |

| Databases consulted | PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, MDPI |

| Type of studies included | Experimental studies |

| Time frame | 2015–present |

| Inclusion criteria | Studies addressing EOs in relation to climate change and abiotic stresses (salt and drought stress) |

| Exclusion criteria | Studies before 2015, non-experimental works, papers not relevant to the selected keywords. |

| Essential Oil Origin | Plant Species Exposed to Stress | Stress | Experimental Conditions and Treatment | Effect of EO Treatment on Plant | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymbra capitata (L.) Cav. | Triticum turgidum L. | Water stress and nutrient stress | Growth chambers. Seed coating treatment. | Increase germination, shoot and roots dry weight and length, N and C content in shoots, Chl and flavonoids, of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. | [100] |

| Origanum vulgare L. Abies alba Mill. | Silene sendtneri Boiss. | No stress | Growth chambers. Seed priming treatment. | O. vulgare EO increased seedling length, RWC, SVI, Chl, and carotenoids of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. A. alba EO increased RWC, SVI, and carotenoids of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. | [93] |

| Thymus capitatus L. | Triticum turgidum L. | No stress | Growth chambers. Seed coating treatment. | Increase germination, shoot and root dry weight and length, amylolytic activity, and phenols of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. | [79] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. Salvia officinalis L. Lavandula x intermedia L. | Triticum aestivum L. | No stress | Growth chambers and field. Seed priming treatment. | Low EOs concentration increased germination, shoot and root length, Chl, RWC, grain yield, and grain weight of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. | [91] |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Triticum turgidum L. | Salt stress | Environment chamber. Seed priming treatment. | High EO concentration increased germination, seedling, root, and leaf length, FW, TLA, MSI, Fv/Fm, carbohydrates, proline, H2O2, MDA, CAT, SOD, POD, and 7 stress-related genes of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. | [99] |

| Lippia alba Mill. | Phaseolus acutifolius L. Solanum lycopersicum L. | Salt stress | Greenhouse. Seed priming treatment. | Increase shoot and root length, biomass, phenols, flavonoids, reducing power, and scavenger activity of treated plants with respect to CTRLs, in both species. | [101] |

| Syzygium aromaticum L. | Glycine max L. | Salt stress during the germination stage | Germination chamber and field trial. Seed priming treatment. | Increase germination, root length, higher percentage of emergence, nodulation, and production than treated plants with industrial treatment and soybean oil controls. | [83] |

| Lippia alba Mill. | Phaseolus acutifolius L. | Salt stress | Greenhouse Seed priming treatment. | Increase STI, Chl, carbohydrates, proline, SOD, POD, PPO, and APX of treated plants with respect to CTRLs. | [102] |

| Malva parviflora L. (in combination with humic acid) | Lavandula latifolia Medik. | No stress | Field trial. Foliar spray. | Increase plant height, branch number, and plant fresh weight, and leaf area compared to CTRLs and other treatments. | [103] |

| Syzygium aromaticum L. Origanum compactum Bentham Cedrus atlantica (Endl.) Carrière Aloysia citriodora Palau Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. Myrtus communis L. Thymus saturejoides Coss. Mentha pulegium L. | Cicer arietinum L. | No stress | Germination chamber. Seed priming treatment. | Low concentration of EOs (0.01%) increases germination rate, total phenolic and flavonoid content, total soluble protein content, and mineral composition (phosphorus and sulfur content) | [104] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borromeo, I.; Giordani, C.; Forni, C. The Role of Plant-Derived Essential Oils in Eco-Friendly Crop Protection Strategies Under Drought and Salt Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 3789. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243789

Borromeo I, Giordani C, Forni C. The Role of Plant-Derived Essential Oils in Eco-Friendly Crop Protection Strategies Under Drought and Salt Stress. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3789. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243789

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorromeo, Ilaria, Cristiano Giordani, and Cinzia Forni. 2025. "The Role of Plant-Derived Essential Oils in Eco-Friendly Crop Protection Strategies Under Drought and Salt Stress" Plants 14, no. 24: 3789. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243789

APA StyleBorromeo, I., Giordani, C., & Forni, C. (2025). The Role of Plant-Derived Essential Oils in Eco-Friendly Crop Protection Strategies Under Drought and Salt Stress. Plants, 14(24), 3789. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243789