Interaction of Soil Texture and Irrigation Level Improves Mesophyll Conductance Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

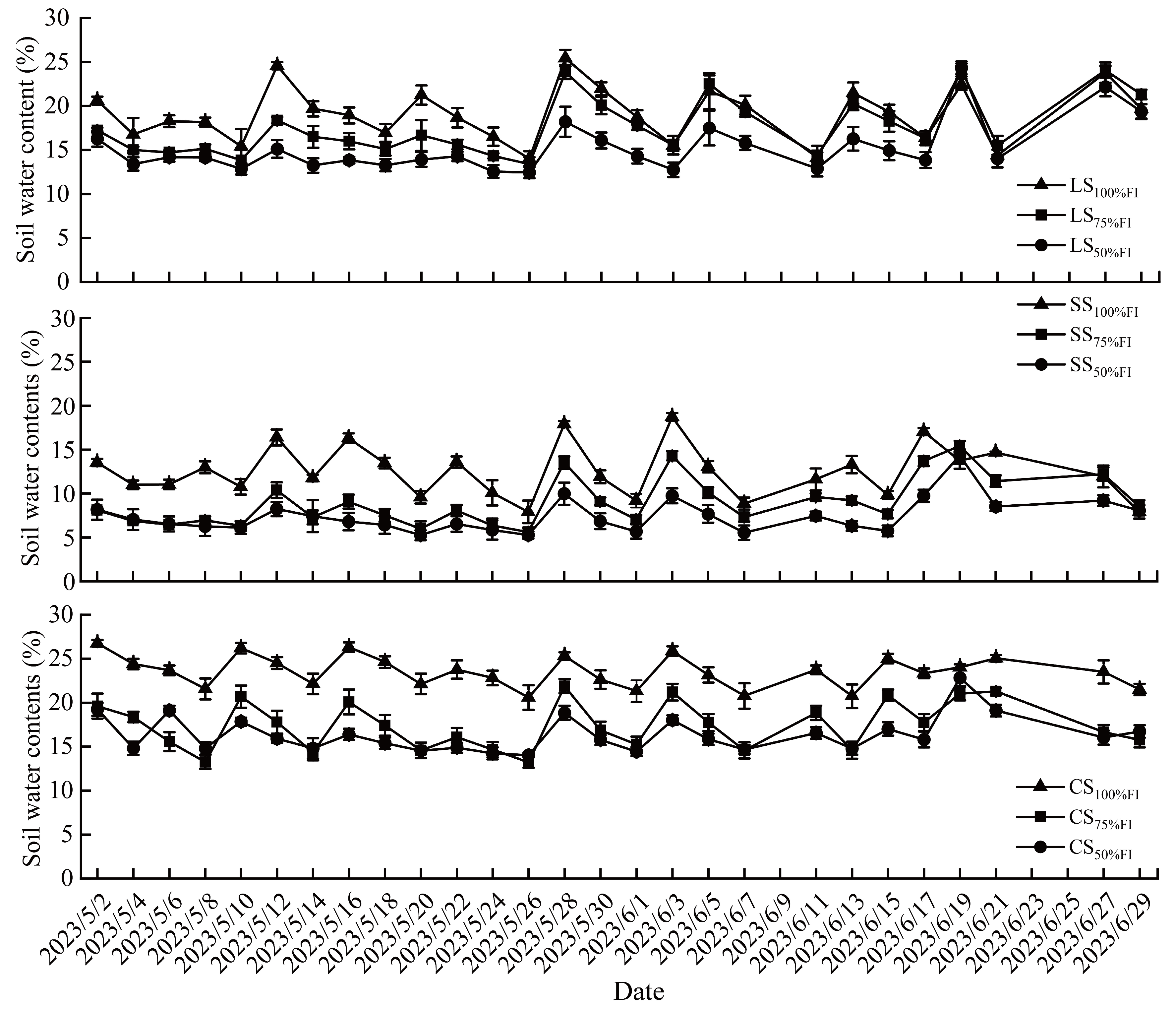

2.1. Changes in Dynamics of Soil Water Content

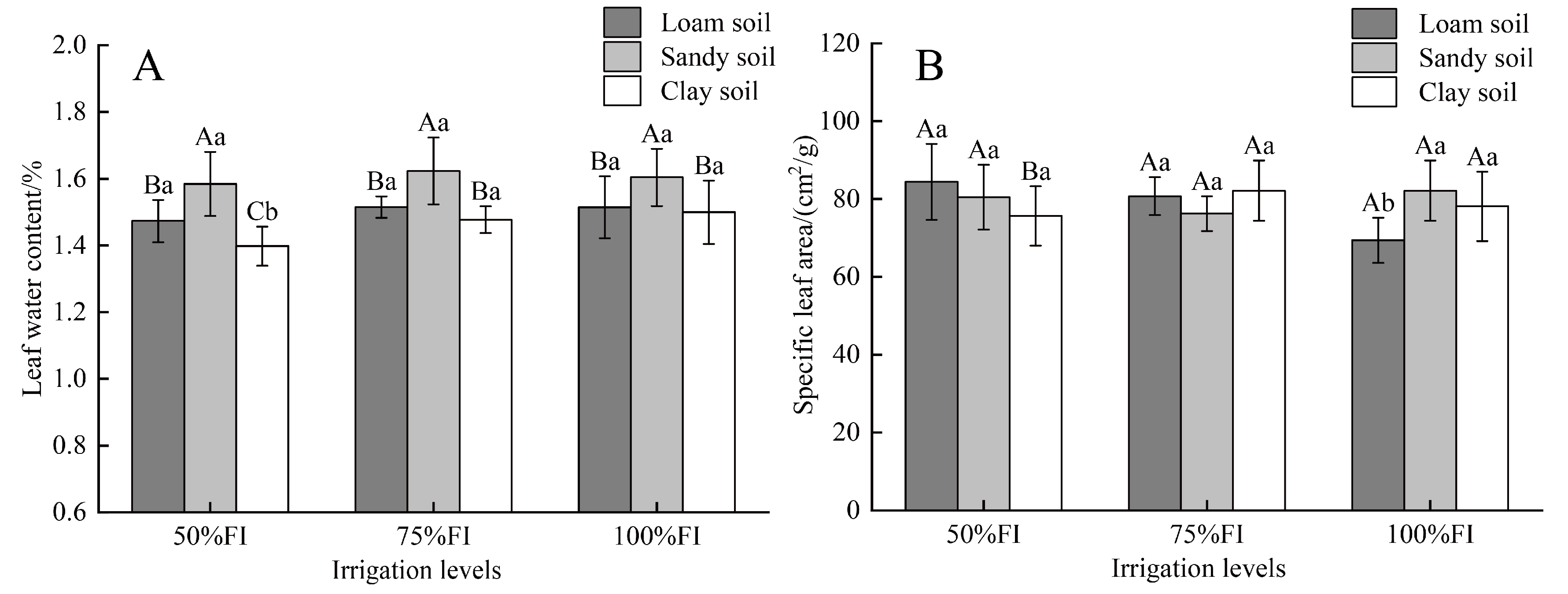

2.2. Changes in Leaf Water Content and Specific Leaf Area

2.3. Responses of gm and the Related Parameters to Interactions of Soil Texture and Irrigation Level

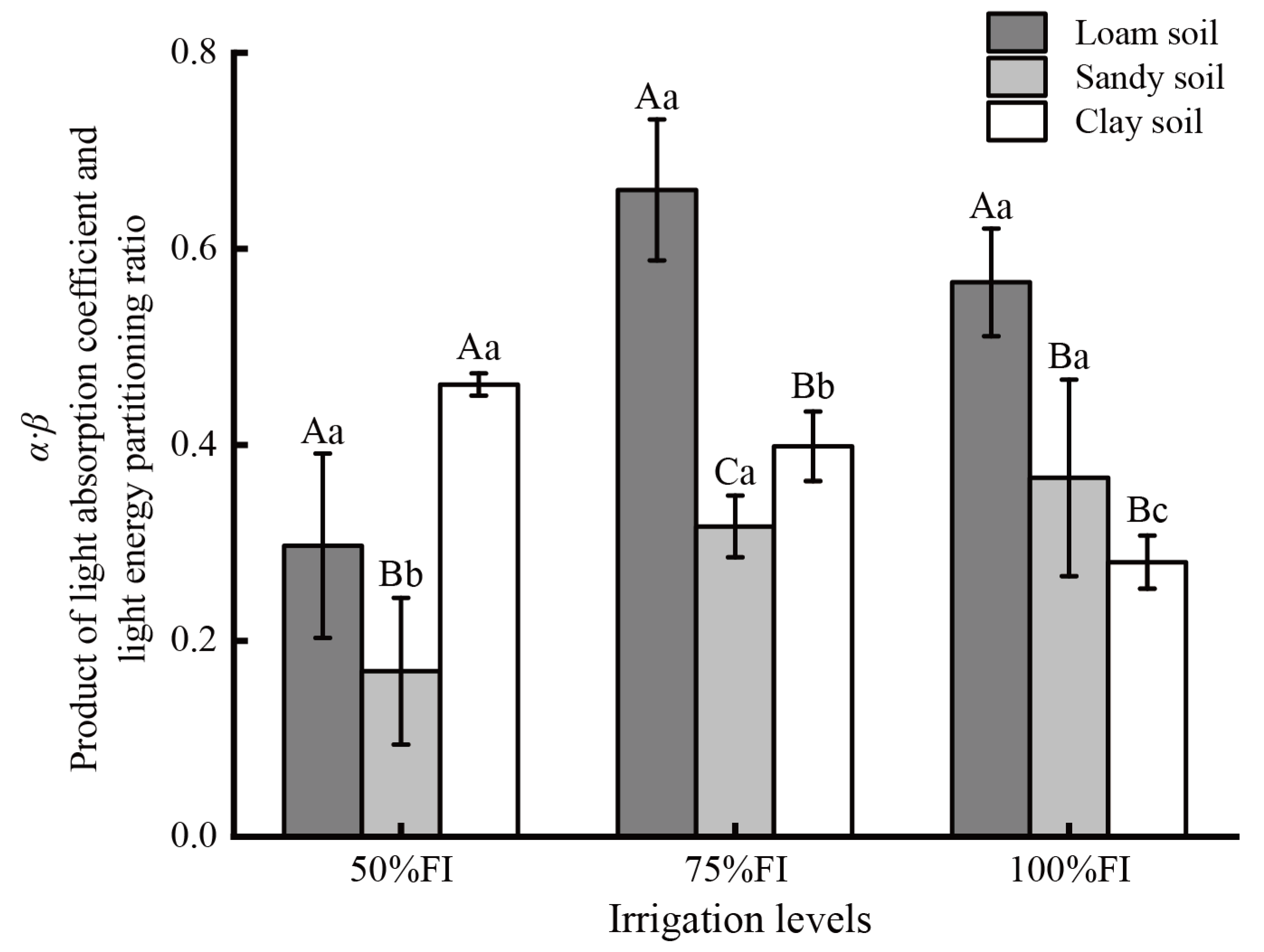

2.4. The Difference of α·β Value Under Different SWC

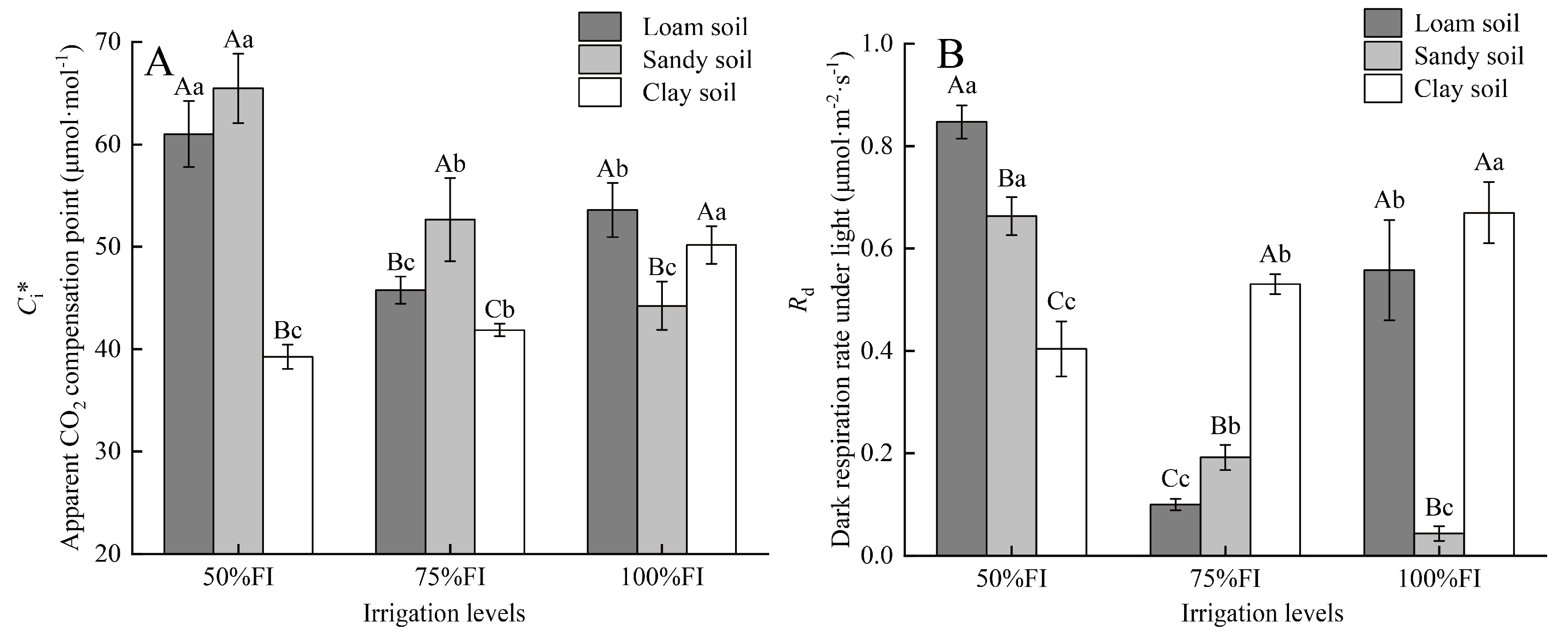

2.5. The Differences of Ci* and Rd Under Different SWC

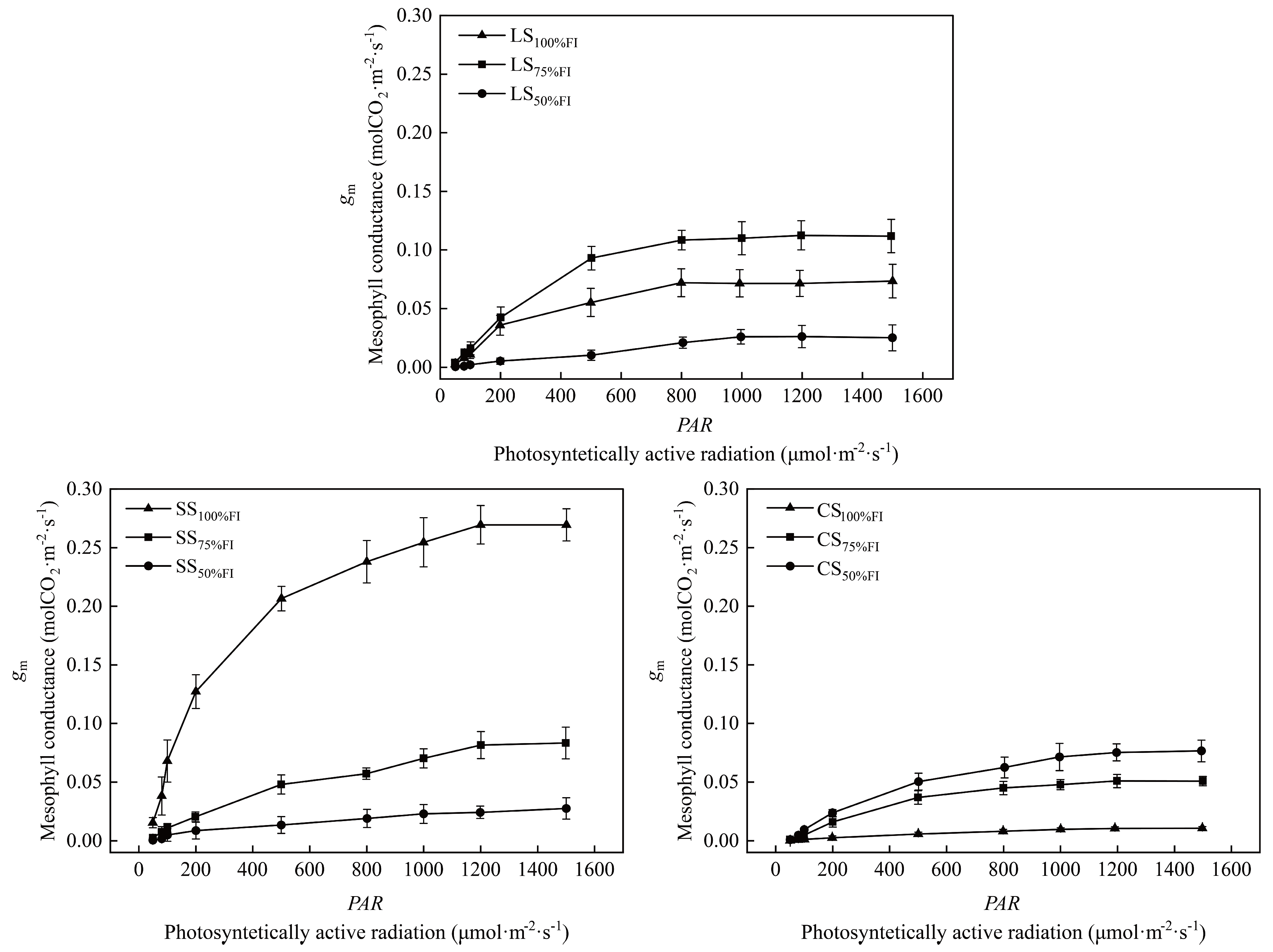

2.6. Responsive Characteristics of gm to PAR Under Different SWC

2.7. Effects of Quantifying Values of α·β on gm and Photosynthetic Biochemical Parameters

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Different Irrigation Levels on Soil Water Content Under Different Soil Textures

3.2. Responses of Leaf Water Content (LWC) and Specific Leaf Area (SLA) to Soil Water Content Under Different Soil Textures

3.3. Responses of Parameter (α·β) and Mesophyll Conductance (gm) to Soil Water Content Under Different Soil Textures

3.4. Responses of the Relationship Between gm and PAR to Soil Water Content Under Different Soil Textures

3.5. Response of Photosynthetic Biochemical Parameters to Soil Water Content Under Different Soil Textures

3.6. Physiological Mechanism of Soil Moisture Affecting Mesophyll Conductance and Photosynthetic Parameters

4. Materials and Methods

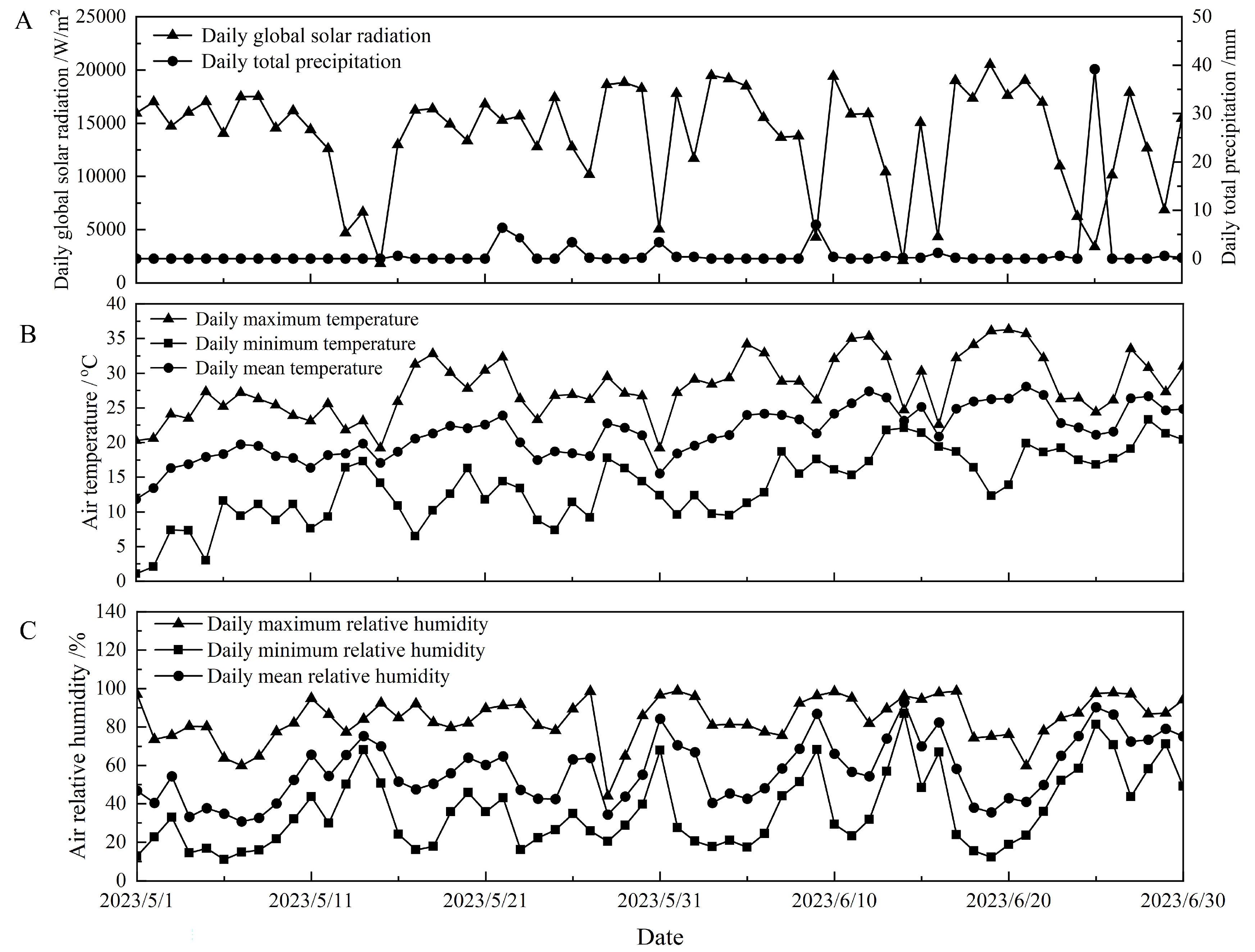

4.1. Experimental Site and Meteorological Conditions

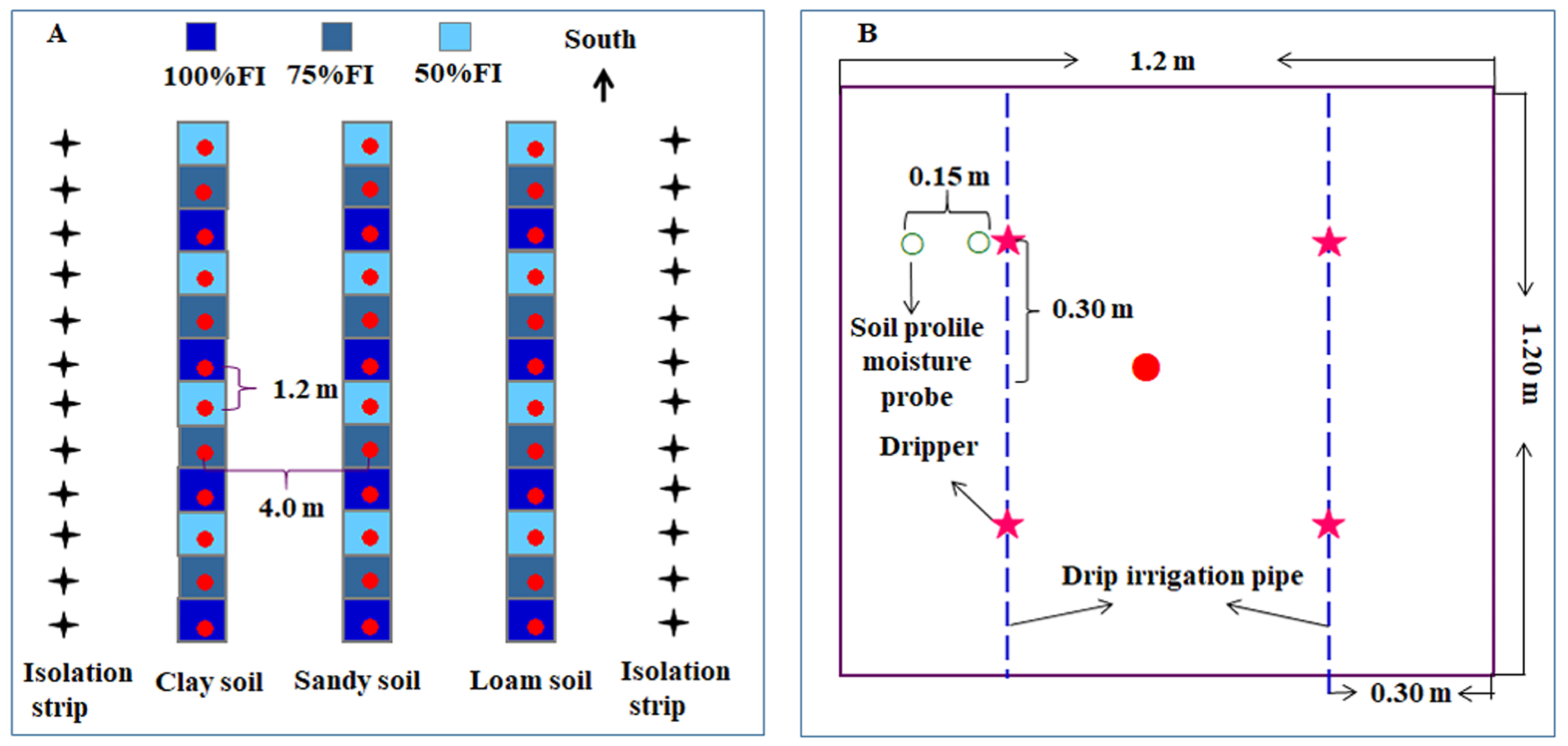

4.2. Experimental Design and Materials

4.3. Experimental Treatment and Irrigation

4.4. Measurements

4.4.1. Soil Water Content (SWC)

4.4.2. Leaf Water Content (LWC) and Specific Leaf Area (SLA)

4.4.3. Mesophyll Conductance (gm)

4.4.4. Response Curves of ΦPSII to PAR

4.4.5. Product of Light Absorption Coefficient and Light Energy Partitioning Ratio (α·β)

4.4.6. Apparent CO2 Compensation Point (Ci*) and Dark Respiration Rate Under Light (Rd)

4.4.7. An-Ci and An-Cc Response Curves and Determination of Photosynthetic Biochemical Parameter

4.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flexas, J.; Ribas-Carbo, M.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Galmés, J.; Medrano, H. Mesophyll conductance to CO2: Current knowledge and prospects. Plant Cell Environ. 2008, 31, 602–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Huang, Z.Y.; Su, X.H.; Siu, A.; Song, Y.P.; Zhang, D.Q.; Fang, Q. Machine learning models for net photosynthetic rate prediction using poplar leaf phenotype data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.P.; Wang, J.Q.; Li, F.Q.; Shi, J.; Gao, J.; Shen, D.Y.; Li, K.Y. Hyperspectral estimation modeling of photosynthetic rate in cotton canopy using chlorophyll data. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2025, 43, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasper, T.B.; Dusenge, M.E.; Breuer, F.; Uwizeye, F.K.; Wallin, G.; Uddling, J. Stomatal CO2 responsiveness and photosynthetic capacity of tropical woody species about taxonomy and functional traits. Oecologia 2017, 184, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Barbour, M.M.; Brendel, O.; Cabrera, H.M.; Carriquí, M.; Díaz-Espejo, A.; Douthe, C.; Dreyer, E.; Ferrio, J.P.; Gago, J.; et al. Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: An unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2012, 193–194, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Yuan, F.H.; Guan, D.X.; Wu, J.B.; Wang, A.Z. Measuring and calculating methods of plant mesophyll conductance: A review. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 1772–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gu, L.; Dickinson, R.E.; Pallardy, S.G.; Baker, J.; Cao, Y.; DaMatta, F.M.; Dong, X.; Ellsworth, D.; van Goethem, D. Asymmetrical effects of mesophyll conductance on fundamental photosynthetic parameters and their relationships estimated from leaf gas exchange measurements. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 978–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.L.; Zhou, B.Z.; Cao, Y.H.; Yang, L.J. Limiting states of photosynthesis of common tree species in the north-subtropical forest based on the improved Farquhar model. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2016, 24, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, Z.Q.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.N.; Niu, Z.M. Photosynthetic responses to the interaction of light intensity and CO2 concentration and photoinhibition characteristics of two apple canopy shapes. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2020, 47, 2073–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Niu, Z.M.; Jiang, C.D.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.N.; Qiao, M.Y. Influences of open-central canopy on photosynthetic parameters and fruit quality of apples (Malus domestica) in the Loess Plateau of China. Hortic. Plant J. 2022, 8, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, G.; Livingston, N. On the need to incorporate sensitivity to CO2 transfer conductance into the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry leaf photosynthesis model. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, X.L.; Li, Q.; Ling, F.L.; Wu, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.A. Effect of salt stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of rice leaves for nitrogen levels. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2018, 53, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, X.T.; Wang, W.E.; Ran, H.; Fang, S.L.; Yang, X. Effects of light intensity and photoperiod on photosynthetic characteristics and chlorophyll fluorescence of hydroponic lettuce. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 32, 1784–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laisk, A.; Loreto, F. Determining photosynthetic parameters from leaf CO2 exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase specificity factor, dark respiration in the light, excitation distribution between photosystems, alternative electron transport rate, and mesophyll diffusion resistance. Plant Physiol. 1996, 110, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.Q.; Zhu, S.D.; Zhu, J.J.; Shen, Z.H.; Cao, K.F. Impact of leaf morphological and anatomical traits on mesophyll conductance and leaf hydraulic conductance in mangrove plants. Plant Sci. J. 2016, 34, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.C.; Galmés, J.; Molins, A.; DaMatta, F.M. Improving the estimation of mesophyll conductance to CO2: On the role of electron transport rate correction and respiration. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3285–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.; Sabate, S.; Gracia, C. Soil water and coupled photosynthesis-conductance models: Bridging the gap between conflicting reports on the relative roles of stomatal, mesophyll conductance, and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; Xia, J.B.; Yang, J.H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Liu, J.T.; Sun, J.K. Comparison of light response models of photosynthesis in leaves of Periploca sepium under drought stress in a sand habitat formed from seashells. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2013, 37, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.M.; Chen, Q.B.; Deng, Q.Q.; Tang, J.; Luo, H.W.; Wu, T.K.; Yang, Z.F. Effects of soil moisture, light, and air humidity on stomatal conductance of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Chin. J. Ecol. 2011, 30, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Y.; Song, J.F.; Zhang, Y.H. Some photosynthetic characteristics of Fraxinus Mandshurica seedlings grown under different soil water potentials. Acta Phytoecol. Sin. 2004, 28, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, H.; Trejo, C.; Peña-Valdivia, C.B.; García-Nava, R.; Conde-Martínez, F.V.; Cruz-Ortega, M.R. Stomatal and nonstomatal limitations of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants under water stress and rewatering: Delayed restoration of photosynthesis during recovery. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 98, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosten, J.H.M.; Pachepsky, Y.A.; Rawls, W.J. Pedotransfer functions: Bridging the gap between available basic soil data and missing soil hydraulic characteristics. J. Hydrol. 2001, 251, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, F.C.; Jiao, J.Y.; Tang, B.Z.; Zhang, Y.F. Soil water availability and holding capacity of different vegetation types in the hilly-gullied region of the Loess Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 3889–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, D.; Tong, B.; Tian, Z.; Heitman, J.L.; Sauer, T.J.; Horton, R. Soil water retention and hydraulic conductivity dynamics following tillage. Soil. Tillage Res. 2019, 193, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.M.; Lei, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yi, X.P.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, Y.L. Drought-introduced variability of mesophyll conductance in Gossypium and its relationship with leaf anatomy. Physiol. Plant 2019, 166, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Forn, D.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Ferrio, J.P.; Mencuccini, M.; Mendoza-Herrer, Ó.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Contrasting functional strategies following severe drought in two Mediterranean oaks with different leaf habits: Quercus faginea and Quercus ilex subsp. rotundifolia. Tree Physiol. 2021, 43, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Hu, W.; Li, Y.X.; Zhu, H.H.; He, J.Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Meng, Y.L.; Chen, B.L.; Zhao, W.Q.; Wang, S.S.; et al. Leaf anatomical alterations reduce cotton’s mesophyll conductance under dynamic drought stress conditions. Plant J. 2022, 111, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Ding, S.Y. Effect of Short-term Drought and Rewatering During the Blooming Stage on Soybean Photosynthesis and Yield. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2009, 44, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Martin, A.; Michelazzo, C.; Torres-Ruiz, J.M.; Flexas, J.; Fernández, J.E.; Sebastiani, L.; Diaz-Espejo, A. Regulation of photosynthesis and stomatal and mesophyll conductance under water stress and recovery in olive trees: Correlation with gene expression of carbonic anhydrase and aquaporins. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 3143–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.W.; Kahlen, K.; Stützel, H. Disentangling the contributions of osmotic and ionic effects of salinity on stomatal, mesophyll, biochemical, and light limitations to photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Qi, X.H.; Xu, C.Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.X.; Sun, P. Short-term responses of leaf gas exchange characteristics to drought stress of Cotinus coggygria seedlings. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2015, 51, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.D.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, M.M. Effect of Soil Texture on Soil Physical Properties and Regulations. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2014, 28, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.P.; Ma, D.H.; Hu, W.; Li, X.L. Land use dependent variation of soil water infiltration characteristics and their scale-specific controls. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 178, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhao, X.N.; Gao, X.D.; Yang, S.W. Deep soil moisture use of planted forests in the Loess Plateau. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2019, 26, 100–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Májeková, M.; Martínková, J.; Hájek, T. Grassland plants show no relationship between leaf drought tolerance and soil moisture affinity, but rapidly adjust to changes in soil moisture. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.X.; Dong, Q.Z.; Zhou, Z.K.; Zhang, Z.G. Leaf traits of the main plant species under different habitat conditions in the Mu Us Sandy Land. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zununjan, Z.; Turghan, M.A.; Sattar, M.; Kasim, N.; Emin, B.; Abliz, A. Combining the fractional order derivative and machine learning for leaf water content estimation of spring wheat using hyperspectral indices. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellstein, C.; Poschlod, P.; Gohlke, A.; Chelli, S.; Campetella, G.; Rosbakh, S.; Canullo, R.; Kreyling, J.; Jentsch, A.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Effects of extreme drought on specific leaf area of grassland species: A meta-analysis of experimental studies in temperate and sub-Mediterranean systems. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Xiang, F.Y.; Zeng, X.G.; Han, Y.C.; Guo, C.; Gu, Y.C.; Chen, F.Y. Physiological Response of Different Strawberry Cultivars Under Drought Stress and Evaluation of Drought Resistance. North. Hortic. 2018, 2, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Z.T.; Zhang, J.R.; Yang, X.F.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.Y.; Shi, L.S. Accurate estimation of winter-wheat leaf water content using continuous wavelet transform-based hyperspectral combined with thermal infrared on a UAV platform. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.Z.; Weng, S.F.; Yuan, Z. Relationships between leaf traits of 5 plantscape shrubs and their responses to the environment in southern China. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2014, 29, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés, J.; Ochogavía, J.M.; Gago, J.; Roldán, E.J.; Cifre, J.; Conesa, M.À. Leaf responses to drought stress in Mediterranean accessions of Solanum lycopersicum: Anatomical adaptations to gas exchange parameters. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 920–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.X.; Wei, L.P.; He, N.P.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z.; Hou, J.H. Vertical variation of leaf functional traits in temperate forest canopies in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 8383–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ding, J.; Tian, Y.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Feng, J.C.; Shi, S. Functional traits and environmental adaptive characteristics of Ammopiptanthus mongolicus. Guihaia 2025, 45, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Niinemets, Ü.; Wright, I.J. Leaf water content contributes to global leaf trait relationships. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.D.; Gao, J. Soil and climatic drivers of plant SLA (specific leaf area). Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 20, e00696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.P.; Qin, G.M.; Li, J.H.; Xu, C.Y.; He, W.J. Response of plant functional traits and leaf economics spectrum to urban thermal environment. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2018, 40, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, O.F.; Stokes, S.M. Coefficient α as a Measure of Test Score Reliability: Review of 3 Popular Misconceptions. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Struik, P.C.; Romero, P.; Harbinson, J.; Evers, J.B.; van der Putten, P.E.; Vos, J. Using combined measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence to estimate parameters of a biochemical C photosynthesis model: A critical appraisal and a new integrated approach applied to leaves in a wheat (Triticum aestivum) canopy. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhang, K.F.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.L. Effect of soil water stress on photosynthetic CO2 uptake and transport of cucumber in a greenhouse. J. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 37, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douthe, C.; Dreyer, E.; Brendel, O.; Warren, C.R. Is mesophyll conductance to CO2 in leaves of three Eucalyptus species sensitive to short-term changes of irradiance under ambient as well as low O2? Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 39, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassiotou, F.; Ludwig, M.; Renton, M.; Veneklaas, E.J.; Evans, J.R. Influence of leaf dry mass per area, CO2, and irradiance on mesophyll conductance in sclerophylls. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 2303–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.W.; Guan, D.X.; Wu, J.B.; Jing, Y.L.; Yuan, F.H.; Wang, A.Z.; Jin, C.J. Day and night respiration of three tree species in a temperate forest of northeastern China. iFor. Biogeosci. For. 2015, 8, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Ma, D.M.; Cai, J.J.; Huang, T.; Ma, Q.L.; Zhao, L.J.; Zhang, Y. Photosynthetic characteristics of alfalfa seedlings under salt stress based on the FvCB model. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G.D.; von Caemmerer, S.; Berry, J.A. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 1980, 149, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genty, B.; Briantais, J.M.; Baker, N.R. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1989, 990, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisker, M.; Apel, H. Inhibition by light of CO2 evolution from dark respiration: Comparison of two gas exchange methods. Photosynth. Res. 2001, 70, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, R.; Mugnozza, G.S.; De Angelis, P.; Matteucci, G. Coupling water sources and carbon metabolism of natural vegetation at integrated time and space scales. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 73, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laisk, A.K. Kinetics of Photosynthesis and Photorespiration in C3 Plants; Nauka Publishing: Moscow, Russia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Von Caemmerer, S. Biochemical Models of Leaf Photosynthesis; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization: Clayton, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variable | Soil Textures | Irrigation Levels | Soil Textures × Irrigation Levels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gm | F | 112.2 | 143.7 | 164.1 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| α·β | F | 2.129 | 52.54 | 4.074 |

| p | 0.148 | <0.001 | 0.0159 | |

| Ci* | F | 36.44 | 63.48 | 26.78 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Rd | F | 105.5 | 78.66 | 132.6 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Vcmax | F | 11.23 | 4.057 | 29.34 |

| p | 0.018 | 0.1403 | <0.001 | |

| Jmax | F | 18.58 | 5.876 | 37.75 |

| p | 0.0111 | 0.0917 | <0.001 | |

| Vtpu | F | 0.2072 | 1.026 | 25.62 |

| Mesophyll Conductance (molCO2·m−2·s−1) | LS100%FI | LS75%FI | LS50%FI | SS100%FI | SS75%FI | SS50%FI | CS100%FI | CS75%FI | CS50%FI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gm′-max | 0.086 ± 0.015 a | 0.150 ± 0.020 a | 0.027 ± 0.007 a | 0.199 ± 0.005 a | 0.075 ± 0.009 b | 0.025 ± 0.011 a | 0.011 ± 0.001 a | 0.051 ± 0.005 a | 0.080 ± 0.009 a |

| gm-max | 0.076 ± 0.015 a | 0.115 ± 0.013 b | 0.028 ± 0.008 a | 0.271 ± 0.015 b | 0.084 ± 0.013 a | 0.028 ± 0.009 a | 0.011 ± 0.001 a | 0.052 ± 0.005 a | 0.077 ± 0.008 a |

| Treatments | Derived from An-Ci Curves | Derived from An-Cc′ Curves (Empirical α·β) | Derived from An-Cc Curves (Quantified α·β) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vcmax-Ci | Vcmax-Cc’ | Vcmax-Cc | |

| LS100%FI | 96.1 ± 8.5 b | 88.2 ± 3.9 a | 91.4 ± 9.2 ab |

| LS75%FI | 110.6 ± 4.6 a | 97.8 ± 8.0 a | 104.6 ± 6.3 a |

| LS50%FI | 88.9 ± 9.5 b | 75.7 ± 6.4 b | 85.9 ± 9.2 b |

| SS100%FI | 84.7 ± 5.7 a | 90.3 ± 3.7 a | 90.1 ± 9.7 a |

| SS75%FI | 80.2 ± 6.2 a | 74.8 ± 7.8 b | 75.9 ± 7.4 ab |

| SS50%FI | 77.0 ± 5.7 a | 52.3 ± 2.4 c | 67.2 ± 7.5 b |

| CS100%FI | 28.8 ± 2.7 b | 25.3 ± 2.4 c | 41.3 ± 4.7 b |

| CS75%FI | 110.5 ± 11.2 a | 118.9 ± 9.1 b | 126.0 ± 11.6 a |

| CS50%FI | 121.4 ± 5.4 a | 138.8 ± 5.6 a | 137.5 ± 14.3 a |

| Treatments | Jmax-Ci | Jmax-Cc′ | Jmax-Cc |

| LS100%FI | 95.5 ± 10.8 ab | 73.4 ± 5.0 b | 92.2 ± 8.3 a |

| LS75%FI | 106.6 ± 7.0 a | 97.3 ± 6.9 a | 103.2 ± 10.0 a |

| LS50%FI | 86.5 ± 8.2 b | 60.6 ± 2.7 c | 77.7 ± 4.4 b |

| SS100%FI | 87.9 ± 7.3 a | 90.9 ± 5.6 a | 90.5 ± 5.7 a |

| SS75%FI | 84.1 ± 3.9 a | 68.0 ± 3.5 b | 66.8 ± 7.1 b |

| SS50%FI | 63.0 ± 7.0 b | 56.8 ± 8.6 b | 60.5 ± 5.3 b |

| CS100%FI | 26.9 ± 3.4 b | 22.2 ± 1.7 c | 39.8 ± 4.6 b |

| CS75%FI | 120.8 ± 6.6 a | 115.2 ± 10.2 b | 133.3 ± 9.4 a |

| CS50%FI | 125.4 ± 7.7 a | 139.7 ± 5.5 a | 135.7 ± 12.8 a |

| Treatments | Vtpu-Ci | Vtpu-Cc′ | Vtpu-Cc |

| LS100%FI | 13.8 ± 0.4 a | 9.0 ± 0.5 b | 9.6 ± 0.2 a |

| LS75%FI | 14.3 ± 1.2 a | 11.3 ± 1.5 a | 9.7 ± 1.5 a |

| LS50%FI | 7.7 ± 1.5 b | 4.4 ± 1.3 c | 4.7 ± 1.4 b |

| SS100%FI | 12.8 ± 2.5 a | 11.0 ± 2.2 a | 11.6 ± 2.3 a |

| SS75%FI | 10.2 ± 0.8 a | 6.8 ± 1.3 b | 6.7 ± 0.8 b |

| SS50%FI | 6.7 ± 1.8 b | 4.1 ± 0.9 c | 4.4 ± 1.0 c |

| CS100%FI | 5.3 ± 1.6 c | 3.3 ± 1.1 c | 4.1 ± 1.6 c |

| CS75%FI | 9.5 ± 1.1 b | 7.1 ± 1.4 b | 7.5 ± 1.4 b |

| CS50%FI | 15.1 ± 1.2 a | 12.0 ± 0.8 a | 11.8 ± 0.9 a |

| Types of Soil Texture | Clay Particle (%) | Silt Particle (%) | Sand Particle (%) | Field Capacity (v/v, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay soil (CS) | 18.58 | 56.71 | 24.73 | 28.1 |

| Sandy soil (SS) | 1.99 | 22.77 | 75.24 | 15.9 |

| Loam soil (LS) | 4.59 | 70.14 | 25.24 | 22.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, L.; Wang, P.; Liang, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, K.; Yu, L.; Liu, S.; Li, Z. Interaction of Soil Texture and Irrigation Level Improves Mesophyll Conductance Estimation. Plants 2025, 14, 3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243784

Lin L, Wang P, Liang Z, Sun M, Zhao Y, Wang H, Zhu K, Yu L, Liu S, Li Z. Interaction of Soil Texture and Irrigation Level Improves Mesophyll Conductance Estimation. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243784

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Lu, Pengpeng Wang, Zhenxu Liang, Mingde Sun, Yang Zhao, Hongning Wang, Kai Zhu, Lu Yu, Songzhong Liu, and Zhiqiang Li. 2025. "Interaction of Soil Texture and Irrigation Level Improves Mesophyll Conductance Estimation" Plants 14, no. 24: 3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243784

APA StyleLin, L., Wang, P., Liang, Z., Sun, M., Zhao, Y., Wang, H., Zhu, K., Yu, L., Liu, S., & Li, Z. (2025). Interaction of Soil Texture and Irrigation Level Improves Mesophyll Conductance Estimation. Plants, 14(24), 3784. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243784