Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria from Kentucky Bluegrass and the Biocontrol Effects of Neobacillus sp. 718 on Powdery Mildew

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

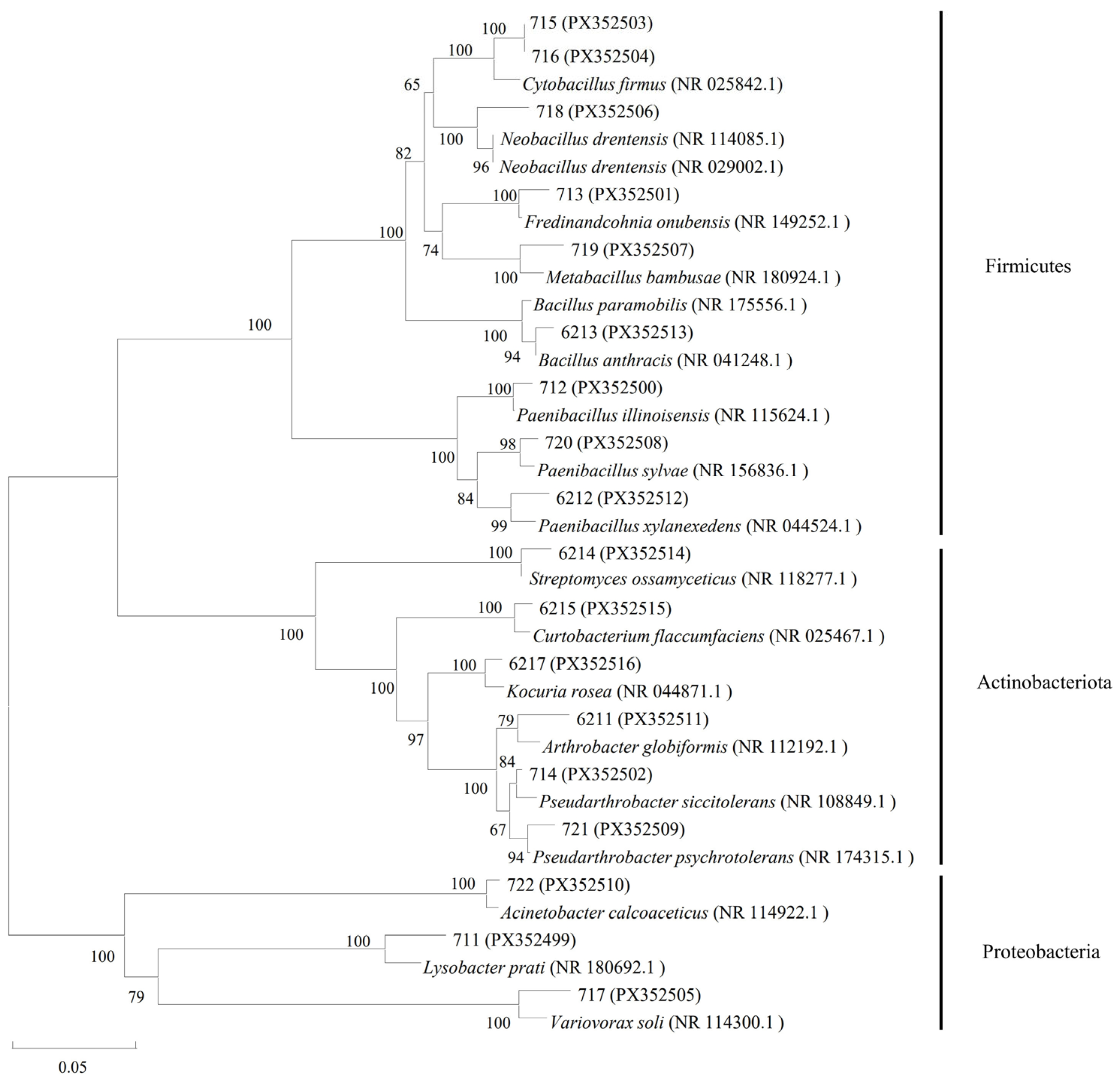

2.1. Molecular Biological Identification and Classification of Endophytic Bacteria Isolated from Kentucky Bluegrass

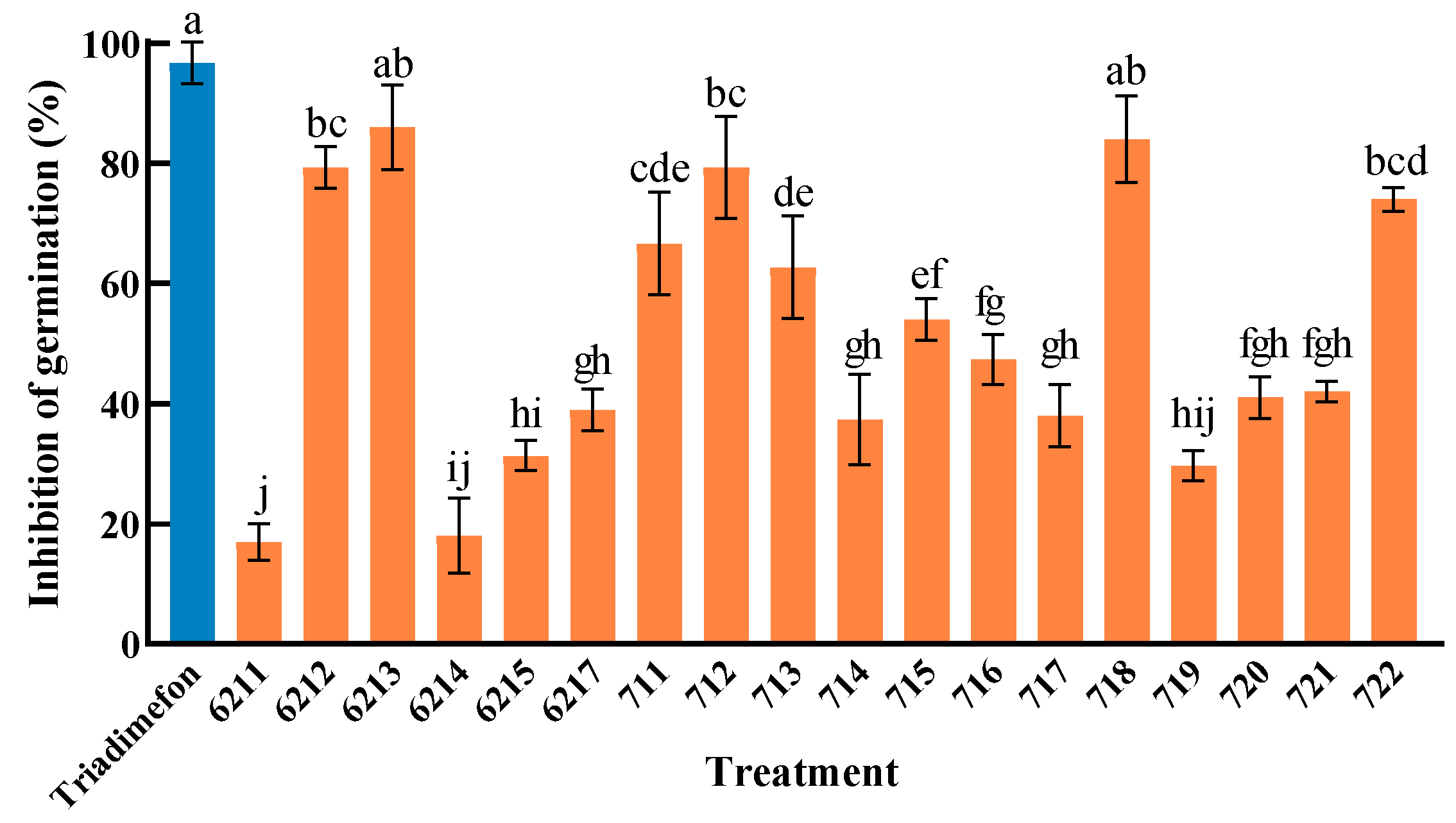

2.2. The Influence of Endophytic Bacteria Isolated from Kentucky Bluegrass on the Germination Inhibition of Powdery Mildew Conidia

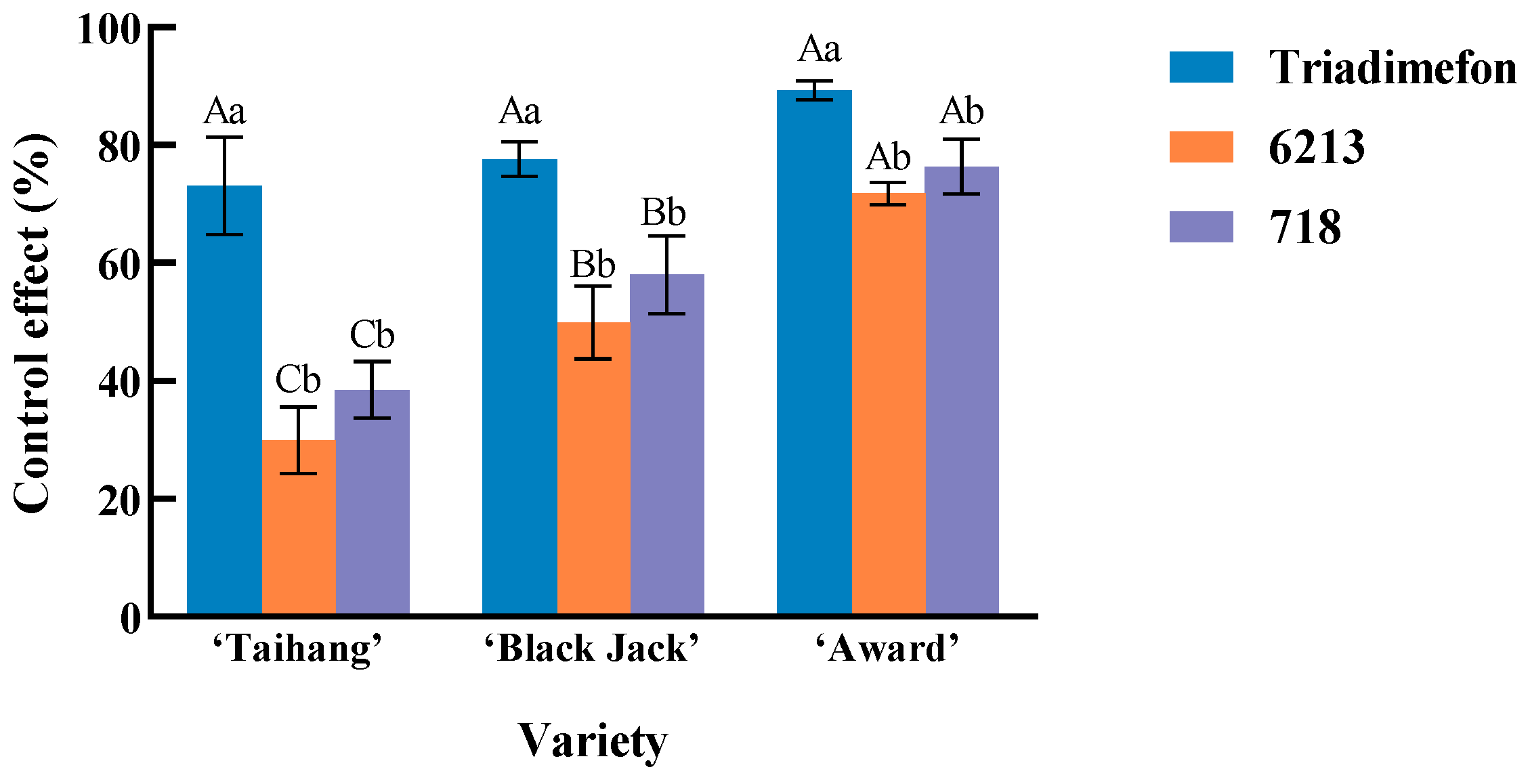

2.3. The Biological Control Effect of Isolate 6213 and Isolate 718 on Kentucky Bluegrass Powdery Mildew

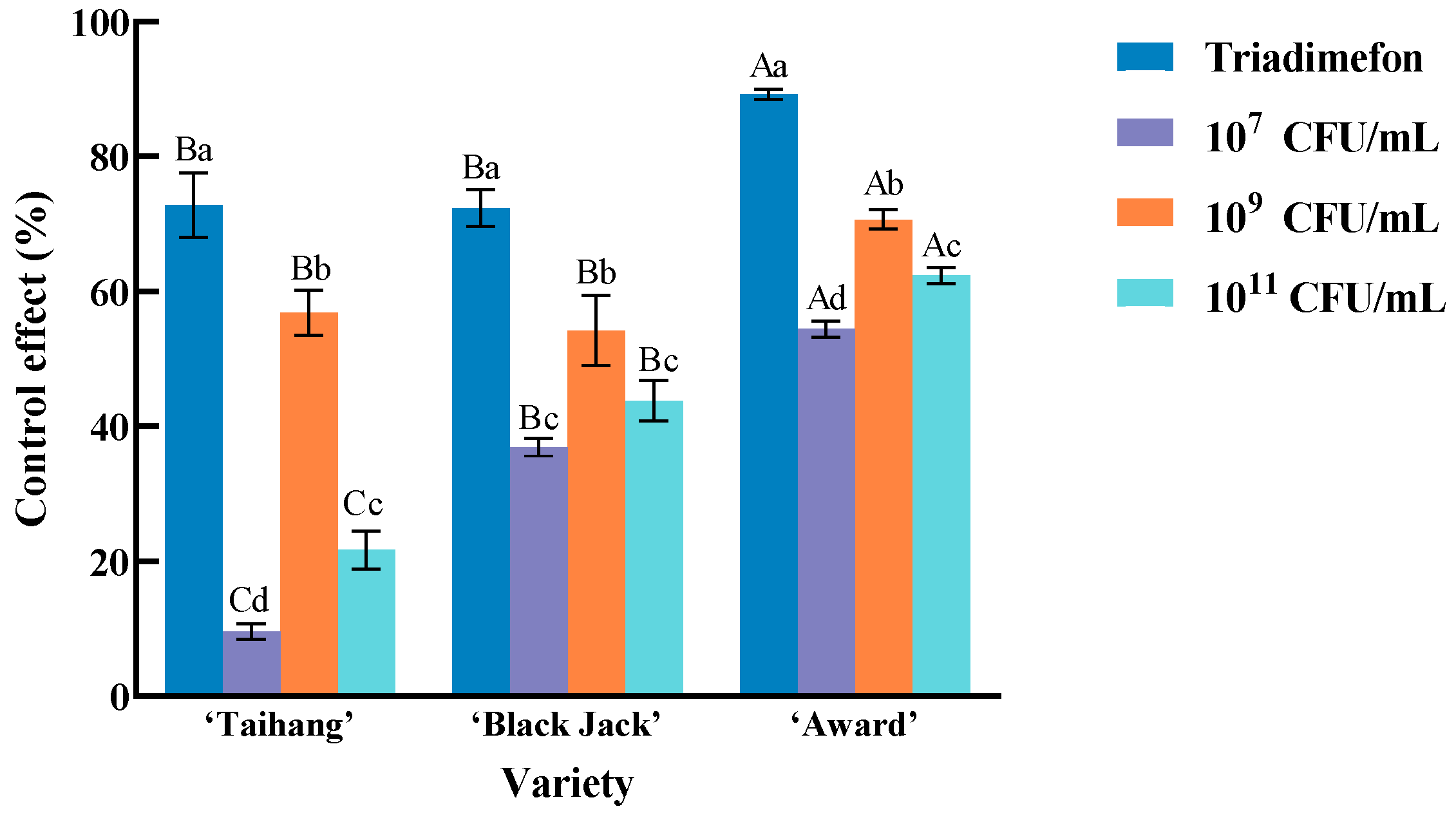

2.4. The Biological Control Effect of Different Concentrations of Isolate 718 on Kentucky Bluegrass Powdery Mildew

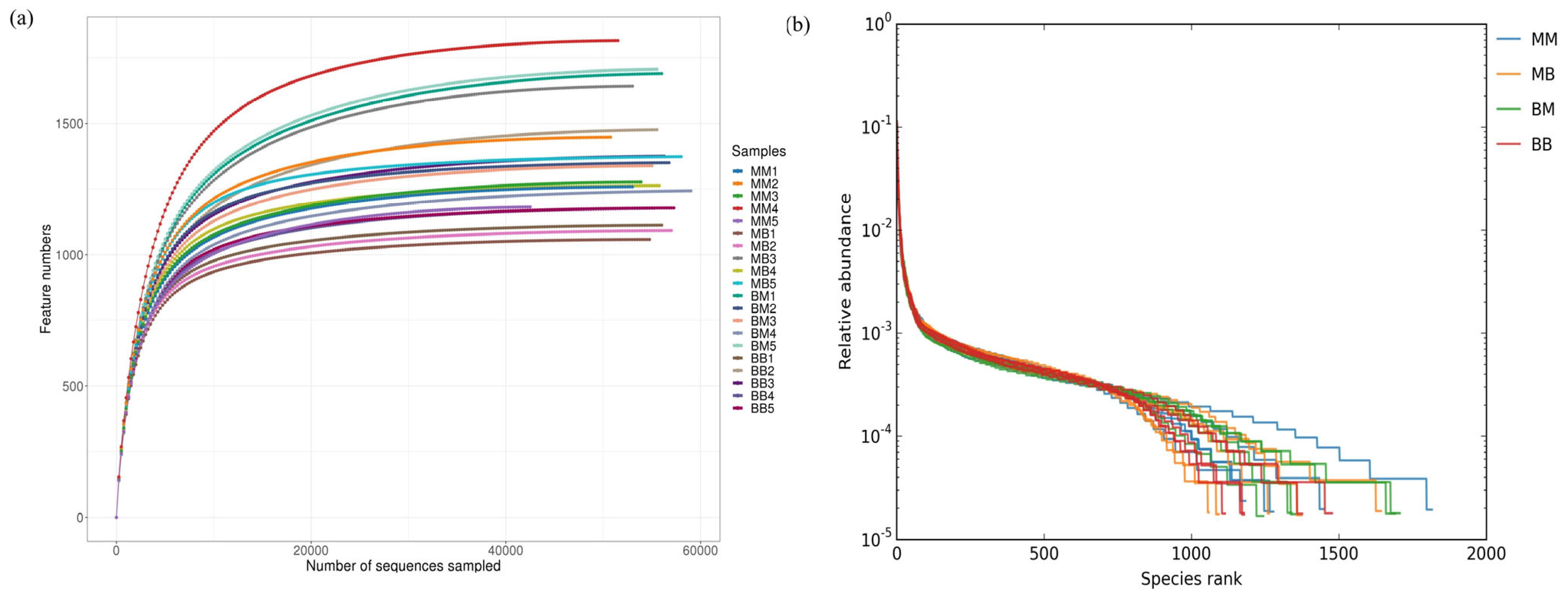

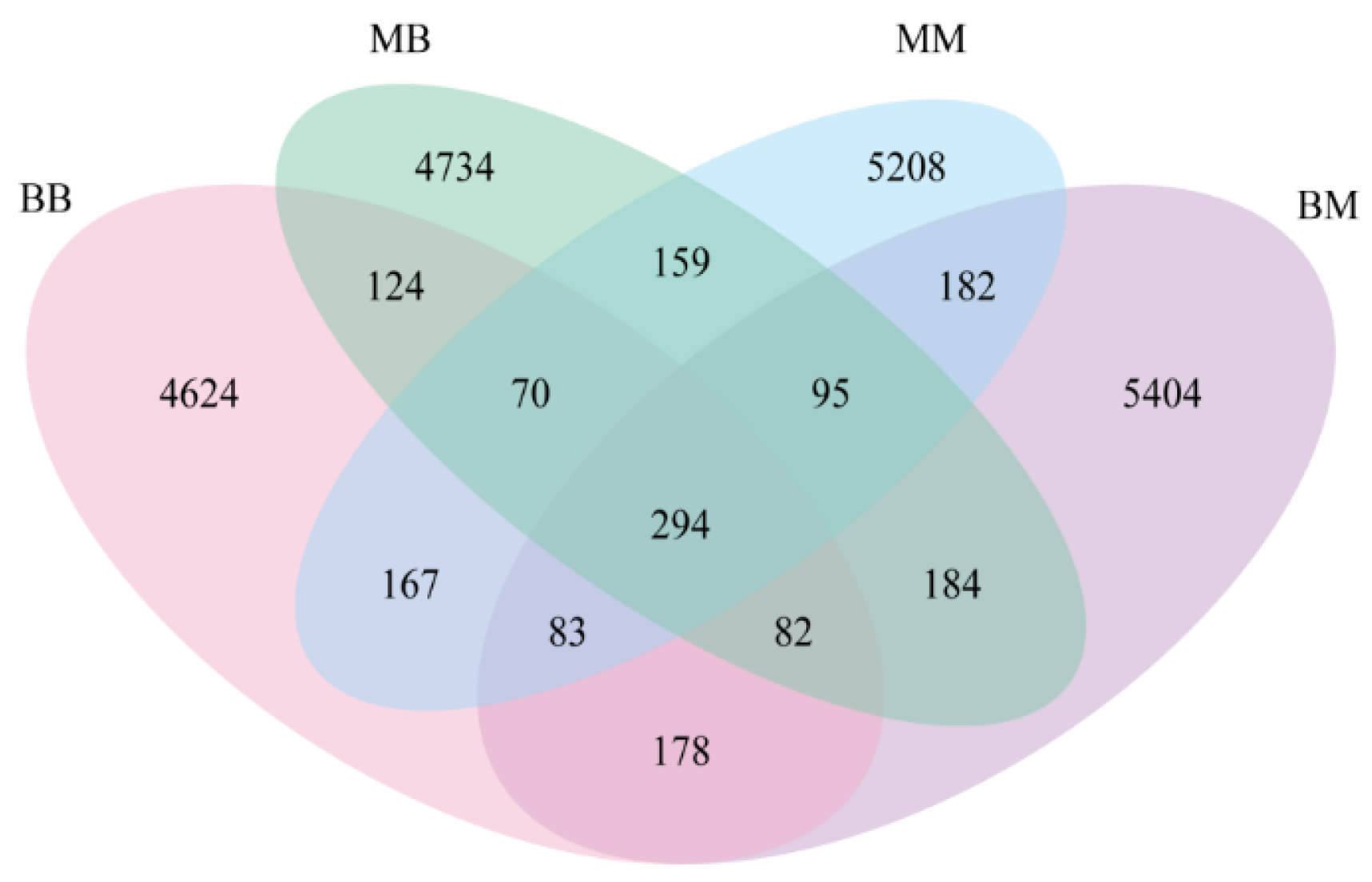

2.5. Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU) Statistics and Analysis

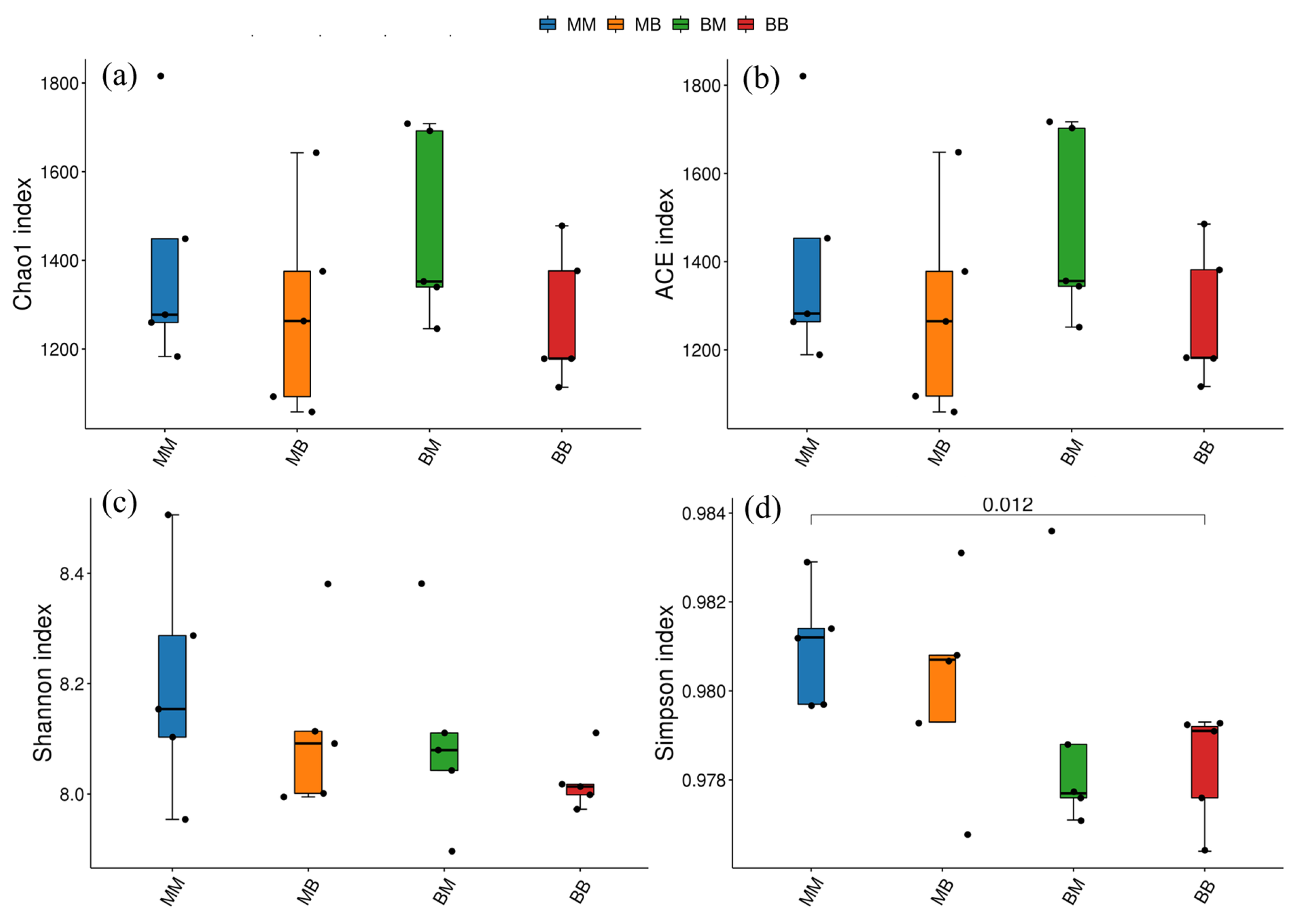

2.6. Analysis of Bacterial Community Diversity

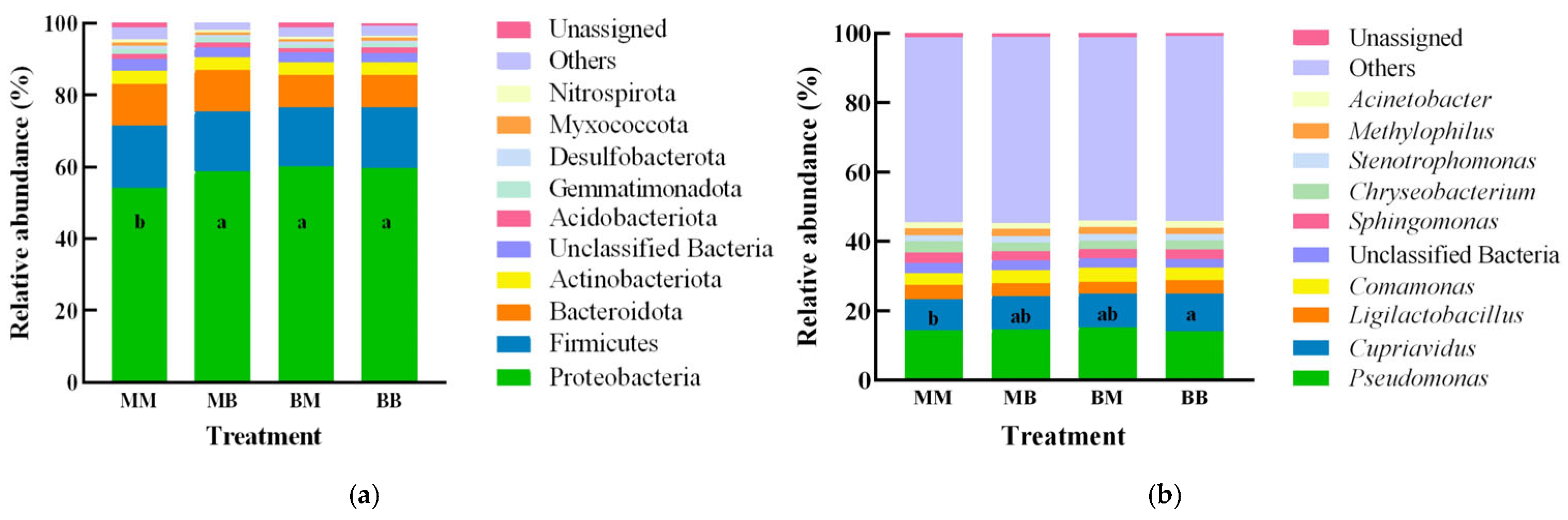

2.7. Taxonomy Richness Analysis

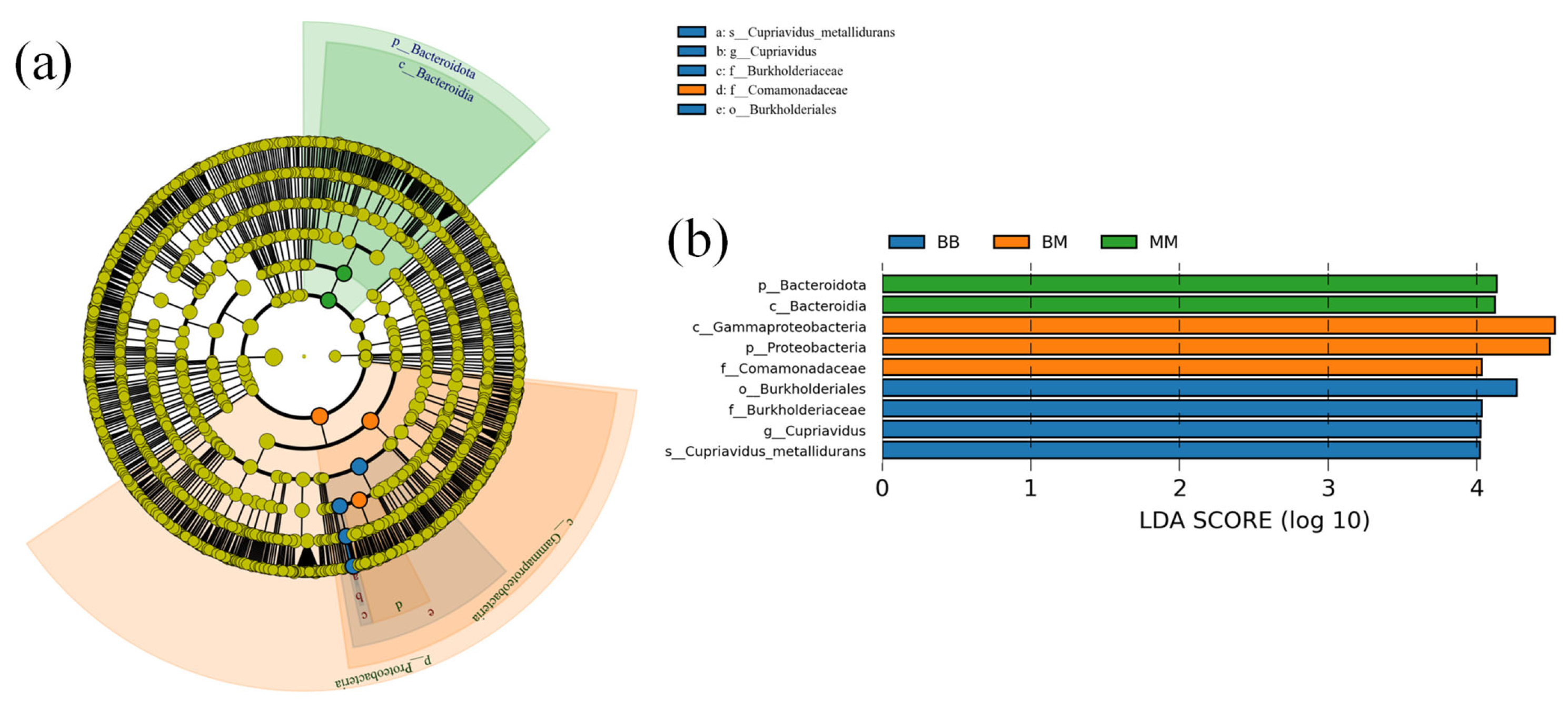

2.8. Analysis of Differences Between Groups

3. Discussion

3.1. Endophytic Bacteria in Kentucky Bluegrass

3.2. Biocontrol Potential of Endophytic Bacteria Against Kentucky Bluegrass Powdery Mildew

3.3. Endophytic Bacterial Community Dynamics and Powdery Mildew Resistance in Kentucky Bluegrass

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant and Pathogen Materials

4.2. Planting Management and Preservation of Pathogen BGP (TG)

4.3. Isolation and Identification of Endophytic Bacteria

4.3.1. Isolation and Purification of Endophytic Bacteria

4.3.2. Identification of Endophytic Bacteria

4.4. Inhibition of Conidia Germination and Control Efficacy of Endophytic Bacteria on Powdery Mildew

4.4.1. Preparation Method of Endophytic Bacteria Suspension

4.4.2. Conidia Germination Inhibition Experiment of Kentucky Bluegrass Powdery Mildew

4.4.3. Determination Method of Control Efficacy of Different Endophytic Bacteria on Powdery Mildew

4.4.4. Control Efficacy of Different Concentrations of Endophytic Bacteria on Powdery Mildew

4.5. Sample Collection for Microbiome Analysis

4.6. High−Throughput 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequencing

4.7. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.8. Analysis of Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, C.; Peng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pedro, G.-C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Sun, X. Transcriptomic profiling of Poa pratensis L. under treatment of various phytohormones. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; Jin, Y.; Sun, H.; Xie, F.; Zhang, L. Biosynthesis and signal transduction of ABA, JA, and BRs in response to drought stress of Kentucky Bluegrass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Shah, F.; Guowen, C.; Chen, Y.; Sumera, A. Determining nitrogen isotopes discrimination under drought stress on enzymatic activities, nitrogen isotope abundance and water contents of Kentucky bluegrass. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatipour, N.; Shams, Z.; Heidari, B.; Richards, C. Genetic variation and response to selection of photosynthetic and forage characteristics in Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) ecotypes under drought conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1239860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, W.S.; Sugiyama, S.-I.; Abbas, A.M. Contribution of avoidance and tolerance strategies towards salinity stress resistance in eight C3 turfgrass species. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2018, 59, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zheng, X.; He, T.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Tan, W.; Xiong, L.; Li, B.; Yin, H.; Agyei, G.D.; et al. The function of PpKCS6 in regulating cuticular wax synthesis and drought resistance of Kentucky bluegrass. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4643–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Xie, F.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Z.; Dong, L.; Qin, L.; Shi, Z.; Xiong, L.; Yuan, R.; Deng, W.; et al. Glutamine synthetase gene PpGS1.1 negatively regulates the powdery mildew resistance in Kentucky bluegrass. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Ji, J.; Shi, W.; Li, Y.F. Occurrence of powdery mildew caused by Blumeria graminis f. sp. poae on Poa pratensis in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 105, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhao, C.; Ma, H. Comparative transcriptome analysis of resistant and susceptible Kentucky bluegrass varieties in response to powdery mildew infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, C.; Renato, D.O.; Antonio, T.O.; Carla, C.; Enrico, P. Genetic analysis of the Aegilops longissima 3S chromosome carrying the Pm13 resistance gene. Euphytica 2003, 130, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, B.; Sheikholeslami, M. Progression of powdery mildew in susceptible-resistant wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivars sown at different dates. J. Phytopathol. 2021, 169, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyang, S.; Wenqi, D.; Yiwei, J.; Yanchao, Z.; Can, Z.; Xinru, L.; Jian, C.; Jinmin, F. Morphology, photosynthetic and molecular mechanisms associated with powdery mildew resistance in Kentucky bluegrass. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Shibata, Y.; Oi, T.; Kawakita, K.; Takemoto, D. Effect of flutianil on the morphology and gene expression of powdery mildew. J. Pestic. Sci. 2021, 46, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Cai, X.; Yang, C.; Xie, L.; Qin, G.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Gong, G.; Chang, X.; Chen, H. Studies on the control effect of Bacillus subtilis on wheat powdery mildew. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4375–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.Q.; Kumar, S.M.; Govindsamy, V.; Annapurna, K. Isolation and characterization of endophytic bacteria from wild and cultivated soybean varieties. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2007, 44, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brader, G.; Compant, S.; Mitter, B.; Trognitz, F.; Sessitsch, A. Metabolic potential of endophytic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 27, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, B.S.; Babalola, O.O. Pharmacological potential of fungal endophytes associated with medicinal plants: A review. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Khaleil, M.M.; Hashem, A.H. Fungal endophytes from leaves of Avicennia marina growing in semi-arid environment as a promising source for bioactive compounds. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 72, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, P.-Y.; Levasseur, M.; Buisson, D.; Touboul, D.; Eparvier, V. Identification of antimicrobial compounds from sandwithia guyanensis-associated endophyte using molecular network approach. Plants 2020, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Brettell, L.E.; Qiu, Z.; Singh, B.K. Microbiome-Mediated Stress Resistance in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongena, M.; Jacques, P. Bacillus lipopeptides: Versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meij, A.; Worsley, S.F.; Hutchings, M.I.; van Wezel, G.P. Chemical ecology of antibiotic production by actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.K.; Johri, B.N. Interactions of Bacillus spp. and plants—With special reference to induced systemic resistance (ISR). Microbiol. Res. 2008, 164, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheibani-Tezerji, R.; Rattei, T.; Sessitsch, A.; Trognitz, F.; Mitter, B. Transcriptome profiling of the endophyte Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN indicates sensing of the plant environment and drought stress. MBio 2015, 6, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lang, D.; Zhang, X. Growth-promoting bacteria alleviates drought stress of G. uralensis through improving photosynthesis characteristics and water status. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 580–589. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.R.; Dai, L.; Xu, G.F.; Wang, H.S. A strain of Phoma species improves drought tolerance of Pinus tabulaeformis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 14, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, S.; Lu, L.; Tian, S. Endophytic Stenotrophomonas SaRB5 enhances willow growth and cadmium phytoremediation via hormone regulation and tissue-specific Cd redistribution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 499, 140223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Xi, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; He, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y. Improvement of salt tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings inoculated with endophytic Bacillus cereus KP120. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 22, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wen, W.; Qin, M.; He, Y.; Xu, D.; Li, L. Biosynthetic mechanisms of secondary metabolites promoted by the interaction between endophytes and plant hosts. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 928967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, C.; Šafran, J.; Mohanaraj, S.; Roulard, R.; Domon, J.M.; Bassard, S.; Facon, N.; Tisserant, B.; Mongelard, G.; Gutierrez, L.; et al. Valorization of sugar beet byproducts into oligogalacturonides with protective activity against wheat powdery mildew. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 24237–24250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asad, S.; Priyashantha, A.K.H.; Tibpromma, S.; Luo, Y.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Fan, Z.Q.; Zhao, L.K.; Shen, K.; Niu, C.; Lu, L.; et al. Coffee-associated endophytes: Plant growth promotion and crop protection. Biology 2023, 12, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, U.; Pal, T.; Yadav, N.; Singh, V.K.; Tripathi, V.; Choudhary, K.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Sunita, K.; Kumar, A.; Bontempi, E.; et al. Current scenario and future prospects of endophytic microbes: Promising candidates for abiotic and biotic stress management for agricultural and environmental sustainability. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 1455–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhan, P.; Bansal, P.; Rani, S. Isolation, identification and characterization of endophytic bacteria from medicinal plant Tinospora cordifolia. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 134, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Pinto, L.F.; Tavares, T.C.; Cardenas-Alegria, O.V.; Lobato, E.M.; de Sousa, C.P.; Nunes, A.R. Endophytic bacteria with potential antimicrobial activity isolated from Theobroma cacao in Brazilian Amazon. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Meng, H.; Shi, W.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ma, K. Endophytic Pantoea sp. EEL5 isolated from Elytrigia elongata improves wheat resistance to combined salinity-cadmium stress by affecting host gene expression and altering the rhizosphere microenvironment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Pang, W.; Feng, J.; Liang, Y. Identification of a Pseudomonas brassicacearum strain as a potential biocontrol agent against clubroot in cruciferous plants through endophytic bacterial community analysis and culture-dependent isolation. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnamte, L.; Vanlallawmzuali; Kumar, A.; Yadav, M.K.; Zothanpuia; Singh, P.K. An updated view of bacterial endophytes as antimicrobial agents against plant and human pathogens. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.F.; Chowdhary, S.; Koksch, B.; Murphy, C.D. Biodegradation of amphipathic fluorinated peptides reveals a new bacterial defluorinating activity and a new source of natural organofluorine compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9762–9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengrand, S.; Pesenti, L.; Bragard, C.; Legrève, A. Bacterial endophytome sources, profile and dynamics—A conceptual framework. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1378436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, E.N.; MacDonald, J.; Liu, L.; Richman, A.; Yuan, Z.C. Current knowledge and perspectives of Paenibacillus: A review. Microb Cell Fact 2016, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Afzal, I.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Sikandar, S.; Shahzad, S. Plant beneficial endophytic bacteria: Mechanisms, diversity, host range and genetic determinants. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 221, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C.; Christensen, M.N.; Kovács, Á.T. Molecular aspects of plant growth promotion and protection by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2021, 34, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.S.; Chary, R.N.; Poornachandra, Y.; Basha, S.A.; Ganesh, V.; Chandrasekhar, C.; Kumar, C.G.; Ramars, A.; Prabhakar, S.; Ahmed, K. Identification, characterization and evaluation of novel antifungal cyclic peptides from Neobacillus drentensis. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 115, 105180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, D.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Improving the activity of an inulosucrase by rational engineering for the efficient biosynthesis of low-molecular-weight inulin. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, A.; S, A.K. Shoot the message, not the messenger-combating pathogenic virulence in plants by inhibiting quorum sensing mediated signaling molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 556. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Pan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Shen, Q.; Yang, J.; Huang, L.; Shen, Z.; Li, R. Plant-microbe interactions influence plant performance via boosting beneficial root-endophytic bacteria. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, G.; Belfiore, N.; Marcuzzo, P.; Spinelli, F.; Tomasi, D.; Colautti, A. Counteracting grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) in grapevine ‘Glera’ using three putative biological control agent strains (Paraburkholderia sp., Pseudomonas sp., and Acinetobacter sp.): Impact on symptoms, yield, and gene expression. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.-S.; Aslam, Z.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, G.-G.; Kang, H.-S.; Ahn, J.-W.; Chung, Y.-R. A bacterial endophyte, Pseudomonas brassicacearum YC5480, Isolated from the root of Artemisia sp. producing antifungal and phytotoxic compounds. Plant Pathol. J. 2008, 24, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkić, I.; Janakiev, T.; Petrović, M.; Degrassi, G.; Fira, D. Plant-associated Bacillus and Pseudomonas antimicrobial activities in plant disease suppression via biological control mechanisms—A review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 117, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.X.; Xu, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Q. Identification and pathogenicity of Blumeria graminis f. sp. poae the BGP(TG) strain isolated from Poa pratensis infected with powdery mildew in Shanxi Province. Microbiol. China 2023, 50, 4389–4400. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Han, L.; Gao, P.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, X.; et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the molecular defense mechanisms of Poa pratensis against powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis f. sp. poae. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tan, F.; Zhong, S.; Li, X.; Gong, G.; Chang, X.; Shang, J.; Tang, S.; et al. Comparative transcriptome profiling of Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici during compatible and incompatible interactions with sister wheat lines carrying and lacking Pm40. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leersnyder, I.; De Gelder, L.; Van Driessche, I.; Vermeir, P. Influence of growth media components on the antibacterial effect of silver ions on Bacillus subtilis in a liquid growth medium. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bai, J.; Cai, Z.; Ouyang, F. Optimization of a cultural medium for bacteriocin production by Lactococcus lactis using response surface methodology. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 93, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalai-Grami, L.; Saidi, S.; Bachkouel, S.; Slimene, I.B.; Mnari-Hattab, M.; Hajlaoui, M.R.; Limam, F. Isolation and characterization of putative endophytic bacteria antagonistic to Phoma tracheiphila and Verticillium alboatrum. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, R.; Munir, S.; He, P.F.; Yang, H.W.; Wu, Y.X.; Wang, J.W.; He, P.B.; Cai, Y.Z.; Wang, G.; He, Y.Q. Biocontrol potential of the endophytic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens YN201732 against tobacco powdery mildew and its growth promotion. Biol. Control 2020, 143, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenbach, D.; Jansen, M.; Franke, R.B.; Hensel, G.; Weissgerber, W.; Ulferts, S.; Jansen, I.; Schreiber, L.; Korzun, V.; Pontzen, R.; et al. Evolutionary conserved function of barley and Arabidopsis 3-KETOACYL-CoA SYNTHASES in providing wax signals for germination of powdery mildew fungi. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, T.; Wen, D.; Bates, C.T.; Wu, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Su, Y.; Lei, J.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y. Nutrient supply controls the linkage between species abundance and ecological interactions in marine bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Name of Isolates | Length of 16S rRNA Gene Sequence (bp) | Accession Number of Isolates | Closest Relative Species | Accession Number of Reference Stains | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6211 | 1425 | PX352511 | Arthrobacter globiformis | NR_112192.1 | 98.80 |

| 6212 | 1453 | PX352512 | Paenibacillus xylanexedens | NR_044524.1 | 98.96 |

| 6213 | 1450 | PX352513 | Bacillus arachidis | NR_041248.1 | 99.77 |

| 6214 | 1428 | PX352514 | Streptomyces ossamyceticus | NR_118277.1 | 99.85 |

| 6215 | 1419 | PX352515 | Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens | NR_025467.1 | 99.58 |

| 6217 | 1423 | PX352516 | Kocuria rosea | NR_044871.1 | 99.51 |

| 711 | 1447 | PX352499 | Lysobacter prati | NR_180692.1 | 99.00 |

| 712 | 1452 | PX352500 | Paenibacillus illinoisensis | NR_115624.1 | 99.50 |

| 713 | 1452 | PX352501 | Fredinandcohnia onubensis | NR_149252.1 | 99.02 |

| 714 | 1378 | PX352502 | Pseudarthrobacter siccitolerans | NR_108849.1 | 99.56 |

| 715 | 1446 | PX352503 | Cytobacillus firmus | NR_025842.1 | 98.75 |

| 716 | 1451 | PX352504 | Cytobacillus firmus | NR_025842.1 | 98.75 |

| 717 | 1435 | PX352505 | Variovorax soli | NR_114300.1 | 99.16 |

| 718 | 1450 | PX352506 | Neobacillus drentensis | NR_114085.1 | 98.56 |

| 719 | 1457 | PX352507 | Metabacillus bambusae | NR_180924.1 | 99.16 |

| 720 | 1459 | PX352508 | Paenibacillus silvae | NR_156836.1 | 99.02 |

| 721 | 1421 | PX352509 | Pseudarthrobacter psychrotolerans | NR_174315.1 | 99.20 |

| 722 | 1441 | PX352510 | Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | NR_114922.1 | 99.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Han, L.; Gao, P.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, H. Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria from Kentucky Bluegrass and the Biocontrol Effects of Neobacillus sp. 718 on Powdery Mildew. Plants 2025, 14, 3758. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243758

Liang Y, Wu F, Zhang Y, Guo Z, Han L, Gao P, Zhao X, Zhu H. Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria from Kentucky Bluegrass and the Biocontrol Effects of Neobacillus sp. 718 on Powdery Mildew. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3758. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243758

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yinping, Fan Wu, Yining Zhang, Zhanchao Guo, Lingjuan Han, Peng Gao, Xiang Zhao, and Huisen Zhu. 2025. "Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria from Kentucky Bluegrass and the Biocontrol Effects of Neobacillus sp. 718 on Powdery Mildew" Plants 14, no. 24: 3758. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243758

APA StyleLiang, Y., Wu, F., Zhang, Y., Guo, Z., Han, L., Gao, P., Zhao, X., & Zhu, H. (2025). Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria from Kentucky Bluegrass and the Biocontrol Effects of Neobacillus sp. 718 on Powdery Mildew. Plants, 14(24), 3758. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243758