Morphological Characteristics of Floral Organs and Their Taxonomic Significance in 23 Species of Bamboo from Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

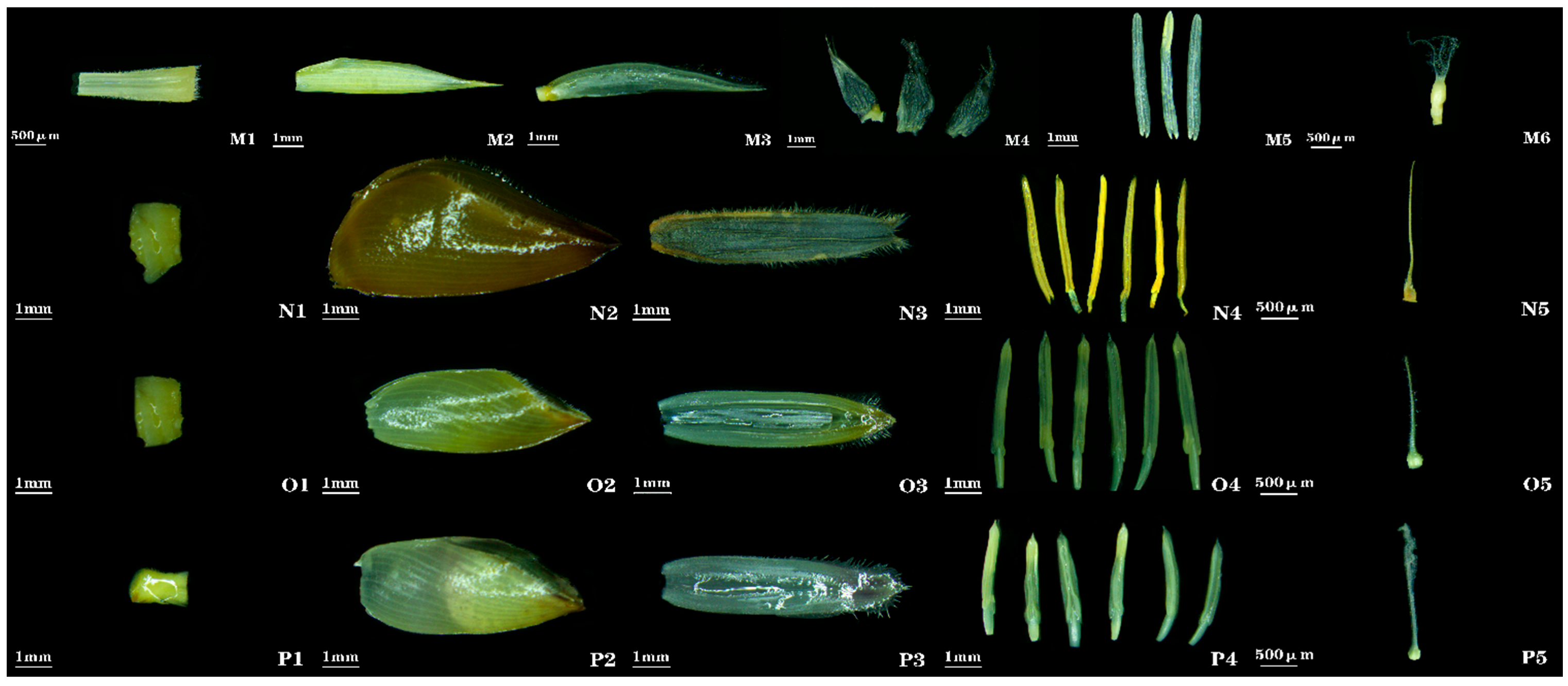

2.1. Morphological Structure and Characteristics of Bamboo Flowers

2.2. Principal Component Analysis of Phenotypic Traits in Bamboo Flowers

2.3. Linear Discriminant Analysis of Bamboo Floral Phenotypic Traits

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, P.F.; Liu, Y.L.; Guo, C.; Jin, G.; Guo, Z.-H.; Mao, L.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Niu, L.-Z.; Wang, Y.-J.; Clark, L.G.; et al. Genome assemblies of 11 bamboo species highlight diversification induced by dynamic subgenome dominance. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora of China; (Poaceae); Wu, Z.-Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.-Y., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2006; Volume 22, ISBN 978-1-930723-50-8. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen, D.H. Why bamboos wait so long to flower. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1976, 7, 347–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holttum, R.E. The typification of the generic name Bambusa and the status of the name Arundo bambos L. Taxon 1956, 5, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Bamboos and Rattans in the World; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, C.; Tang, G. The present status and problems of bamboo classification in China. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 1993, 36, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Systematic Taxonomy of the Subtribe Sasinae; Nanjing Forestry University: Nanjing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y. Key to the Genera and Species of Gramineae in China: With Systematic List; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, B. A Revision of the Genera of Bambusoideae in the World. J. Bamboo Res. 1982, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, W.D.; Renvoize, S.A. Genera Graminum: Grasses of the World; HMSO: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xue, J. Studies on the Genus Dendrocalamus in China (I). J. Bamboo Res. 1988, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Yang, H.-Q.; Li, D.-Z. Highly heterogeneous generic delimitation within the temperate bamboo clade (Poaceae: Bambusoideae): Evidence from GBSSI and ITS sequences. Taxon 2008, 57, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Zeng, C.X.; Li, D.Z. Complex evolution in Arundinarieae (Poaceae: Bambusoideae): Incongruence between plastid and nuclear GBSSI gene phylogenies. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012, 63, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Shi, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Ma, N.; Yang, H.; Zhou, D.; Lu, X. Atlas of Chinese Bamboos; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C. Speciation of the Bambusa–Dendrocalamus–Gigantochloa Complex: Molecular Evidence of Hybridization. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X. Preliminary Study on the Molecular Systematics of the Bambusa Group in Bambusoideae. Ph.D. Dissertation, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, T.; Shi, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, L. A New Species of Yushania Keng f. and Supplement of Flower of Fargesia lincangensis Yi from West Yunnan, China. Bull. Bot. Res. 2008, 28, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. Discussion on Dendrocalamus in China. J. Bamboo Res. 1989, 8, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Committee of Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae. Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1996; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kelchner, S.A.; Clark, L.G. Molecular evolution and phylogenetic utility of the chloroplast rpl16 intron in Chusquea and the Bambusoideae (Poaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 8, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsova, M.S.; Clark, L.G.; Dransfield, J.; Soreng, R.J.; Fisher, A.E.; Kelchner, S.A.; Paula, D.S.; Welker, C.A.D.; Barberá, P.; Cano, Á.A.; et al. World Checklist of Bamboos and Rattans; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Huang, H.; He, F.; Zhang, W. Microsporogenesis and Formation of Male Gametophyte of Phyllostachys violascens. J. Bamboo Res. 1999, 18, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Pu, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, L. Morphological Structure of the Reproductive Organs and Development of Female and Male Gametophytes of Dendrocalamus sinicus. Bull. Bot. Res. 2006, 26, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ding, Y. Development of the Male and Female Gametophytes in Shibataea chinensis (Bambusoideae). Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occid. Sin. 2012, 32, 907–914. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, R.; Dong, X.; Ding, Y. The development of flowering bud differentiation and male gametophyte of Bambusa multiplex. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 39, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Yang, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Studies on the flower morphology and structure in Bambusa eutuldoides McClure var. viridi-vittata(W.T.Lin)Chia J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 40, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, N.; Tong, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Floral Morphology and Development of Female and Male Gametophyte of Bambusa intermedia Hsueh et Yi. Bull. Bot. Res. 2017, 37, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, S. Floral Morphology and Development of Female and Male Gametophytes of Neomicrocalamus prainii. Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occid. Sin. 2019, 39, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Fu, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, R.; Dong, X. Anther development and floral morphology characteristics of Bambusa oldhami ‘Xia Zao’ ZSX. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 43, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Chu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Dong, X.; Qu, Z. Study on the Morphology and Structure of Bambusa rigida Flowers. For. Res. 2020, 33, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Xue, J.; Yang, Y.; Hui, C.; Wang, J. Study on Flowering Phenomenon and its Type of Bamboo in Yunnan in Past Fifteen Years. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2000, 36, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L. A Preliminary Discussion on the Taxonomic Values of The Main Characters of Reproductive Organ of Poaceae and their Ranks Suitable for Differentiating Taxa. Bull. Bot. Res 2002, 22, 278–284. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Shi, W.; Miao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Y. Research Advances in Reproduction Biology of Bamboos. World Bamboo Rep. 2010, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, B. A Revision of the Genera of Bambusoideae in the World (IV). J. Bamboo Res. 1983, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ohrnberger, D. The Bamboos of the World: Annotated Nomenclature and Literature of the Species and the Higher and Lower Taxa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.Q.; Yang, J.B.; Peng, Z.H.; Gao, J.; Yang, Y.M.; Peng, S.; Li, D.Z. A molecular phylogenetic and fruit evolutionary analysis of the major groups of the paleotropical woody bamboos (Gramineae: Bambusoideae) based on nuclear ITS, GBSSI gene and plastid trnL-F DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 48, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.K.; Lu, Q.F.; Zhu, Z.X.; Liu, S.H.; Zhong, H.; Xiao, Z.Z.; Zou, Y.G.; Gu, L.J.; Du, X.H.; Cai, H.J.; et al. Exploring phylogenetic relationships within the subgenera of Bambusa based on DNA barcodes and morphological characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitchak, N.; Traiperm, P.; Staples, G.; Pornpongrungrueng, P. Species delimitation of some Argyreia (Convolvulaceae) using phenetic analyses: Insights from leaf anatomical data reveal a new species. Botany 2018, 96, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Deng, L.; Chu, C.; Zhan, H.; Wang, S. Morphological and Anatomical Observations of Floral Organs and Sterility Analysis of Fargesia yuanjiangensis. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2020, 56, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, H. Pollen Germination Percentage and the Floral Character of Five Bamboo Species. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2008, 44, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus | Species | Spikelet Shape | Spikelet Length (cm) | Spikelet Width (mm) | Rachilla Type | Rachilla Length (mm) | Lemma Shape | Pubescence on Lemma Margins | Lemma Length (mm) | Pubescence on Palea Margins | Palea Length (mm) | Pistil Type | Ovary Shape | Stigmas Number | Stamen Number | Lodicule Number | Lodicule Shape |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bambusa | Bambusa sinospinosa | Linear lanceolate | 2.7–3.8 | 2.7–4.1 | Nearly hollow | 3.8–4.8 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 7.3–8.2 | Yes | 7.1–9.0 | Long style and short stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Obovate |

| Bambusa ventricosa | Linear lanceolate | 4.9–5.9 | 3.0–4.5 | Nearly hollow | 1.9–3.1 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 9.2–10.5 | Yes | 9.7–11.3 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Obovate | |

| Bambusa eutuldoides var. vviridivittata | Linear lanceolate | 2.8–3.8 | 4.7–7.5 | Nearly hollow | 2.7–3.7 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 9.4–11.0 | Yes | 9.7–11.1 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 2 | 6 | 3 | Irregular | |

| Bambusa tuldoides | Linear lanceolate | 3.4–4.6 | 2.4–4.0 | Near-solid | 2.8–4.2 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 11.5–13.5 | Yes | 10.7–12.9 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Obovate | |

| Bambusa textilis | Linear lanceolate | 2.9–4.1 | 2.9–5.3 | Nearly hollow | 3.2–4.8 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 12.3–14.5 | Yes | 12.3–13.7 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Spoon-shaped, obovate | |

| Bambusa rigida | Linear lanceolate | 2.1–4.3 | 4.8–7.2 | Nearly hollow | 2.7–3.7 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 11.7–13.3 | Yes | 9.7–10.9 | Long style and short stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Semi-spoon-shaped, Oblanceolate | |

| Bambusa rutila | Linear lanceolate | 6.2–7.7 | 2.4–3.9 | Nearly hollow | 2.3–3.1 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 9.2–11.1 | Yes | 11.0–12.6 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Ovate | |

| Bambusa cerosissima | Long-ovate | 1.8–3.2 | 6.6–8.0 | Nearly hollow | 3.5–5.0 | Broadly ovate | No | 9.3–9.9 | No | 9.0–10.2 | Short style and short stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Ovate | |

| Bambusa intermedia | Linear lanceolate | 4.3–5.1 | 2.0–3.2 | Nearly hollow | 1.8–2.8 | Ovate-lanceolate | No | 11–12.2 | Yes | 12.2–14.4 | Short style and short stigma | Obovate | 1 | 6 | 3 | Elongated-lanceolate | |

| Bambusa emeiensis | Long oval shape | 1.9–3.5 | 5.1–8.1 | Near-solid | 1.5–2.9 | Broadly ovate | Yes | 8.2–9.8 | Yes | 7.8–9.4 | Long style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Oblong-lanceolate | |

| Gigantochloa | Gigantochloa sp. | Lanceolate | 2.5–2.9 | 1.4–2.9 | Near-solid | 3.1–4.3 | Oblong-lanceolate | No | 6.7–8.5 | Yes | 5.2–6.2 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 3 | 3 | Ovo-lanceolate |

| Gigantochloa | Gigantochloa | Oblong | 1.9–2.6 | 5.4–6.8 | Near-solid | 4.56 ± 0.541 | Broadly ovate | Yes | 8.4–10.3 | Yes | 7.0–8.6 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 3 | 6 | 3 | Ovo-lanceolate |

| Pleioblastus | Pleioblastus fortunei | Linear lanceolate | 6.7–7.1 | 1.4–3.5 | Near-solid | 7.11 ± 0.352 | Lanceolate | No | 12.8–14.4 | Yes | 11.9–13.3 | Short style and long stigma | Elliptical | 3 | 3 | 3 | Oblong-lanceolate |

| Dendrocalamus | Dendrocalamus sinicus | Ovate | 3.0–3.5 | 6.2–8.1 | Near-solid | 2.67 ± 0.086 | Broadly ovate | Yes | 24.3–25.7 | Yes | 24.7–26.3 | Long style and long stigma | Globular | 1 | 6 | 0 | / |

| Dendrocalamus giganteus | Ovate | 2.5–2.8 | 4.5–6.1 | Near-solid | 0.59 ± 0.017 | Broadly ovate | Yes | 9.3–11.1 | Yes | 9.1–10.9 | Long style and long stigma | Globular | 1 | 6 | 0 | / | |

| Dendrocalamus fugongensis | Ovate | 2.5–3.2 | 5.7–8.1 | Near-solid | 1.03 ± 0.210 | Broadly ovate | Yes | 11.5–12.9 | Yes | 11.5–12.9 | Long style and long stigma | Globular | 1 | 6 | 0 | / | |

| Dendrocalamus hamiltonii | Ovate | 0.5–1.2 | 4.9–7.0 | Near-solid | 1.2 ± 0.073 | Broadly ovate | Yes | 7.7–10.3 | Yes | 8.4–10.0 | Long style and long stigma | Globular | 1 | 6 | 0 | / | |

| Phyllostachys | Phyllostachys sulphurea | Narrowly lanceolate | 2.3–3.2 | 0.6–2.5 | Near-solid | 5.31 ± 0.351 | Lanceolate | Yes | 18.6–20.0 | Yes | 19.7–21.3 | Long style and short stigma | Obovate | 1 | 3 | 3 | Lanceolate |

| Phyllostachys glauca | Narrowly lanceolate | 3.1–3.6 | 1.5–3.1 | Near-solid | 2.53 ± 0.0231 | Lanceolate | Yes | 19.1–21.3 | Yes | 15.5–17.5 | Long style and short stigma | Obovate | 1 | 3 | 3 | Lanceolate | |

| Phyllostachys nigra | Lanceolate | 2.2–3.4 | 3.8–5.2 | Near-solid | 3.29 ± 0.294 | Lanceolate | Yes | 15.4–16.6 | Yes | 14.1–15.3 | Long style and short stigma | Obovate | 1 | 3 | 3 | Obovate | |

| Schizostachyum | Schizostachyum brachycladum | Lanceolate | 2.3–3.1 | 2.5–4.0 | Near-solid | 2.25 ± 0.0621 | Ovoid-caudal pointed | No | 10.2–12.4 | No | 6.6–8.6 | Long style and short stigma | Broadly ovate | 1 | 6 | 3 | Oblong-lanceolate |

| Fargesia | Fargesia yuanjiangensis | Linear lanceolate | 3.1–4.2 | 1.8–3.1 | Near-solid | 5.15 ± 0.754 | Lanceolate | Yes | 8.8–10.0 | Yes | 7.8–9.6 | Short style and long stigma | Obovate | 2 | 3 | 3 | Ovate |

| Fargesia fungosa | Lanceolate | 3.4–4.1 | 1.9–3.3 | Near-solid | 4.46 ± 0.544 | Lanceolate | Yes | 16.4–17.8 | Yes | 11.1–13.3 | Short style and long stigma | Elliptical | 2 | 3 | 3 | Lanceolate |

| Principal Component | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load factor | |||||

| Spikelet morphology | 0.3564 | −0.1738 | 0.1103 | −0.012 | 0.1417 |

| Spikelet length | −0.2452 | −0.0605 | −0.3522 | −0.1068 | −0.5006 |

| Spikelet width | 0.1478 | 0.3505 | −0.0126 | 0.0412 | 0.4417 |

| Lemma length | 0.1787 | −0.2805 | −0.4223 | −0.2799 | 0.2219 |

| Lemma shape | 0.347 | −0.1147 | 0.1759 | −0.0825 | −0.2498 |

| Pubescence on lemma margins | 0.3177 | −0.1593 | 0.0118 | 0.3703 | 0.2023 |

| Palea length | 0.1643 | −0.2022 | −0.5546 | −0.2395 | 0.1897 |

| Pubescence on palea margins | 0.0047 | −0.084 | −0.4163 | 0.6505 | −0.1439 |

| Ovary shape | 0.3048 | 0.1116 | 0.12 | −0.3274 | −0.4039 |

| Stigma number | −0.3313 | 0.1095 | 0.0532 | 0.2175 | 0.0282 |

| Pistil type | 0.2315 | 0.2922 | −0.0917 | 0.2311 | −0.0764 |

| Stamen number | −0.0042 | 0.4673 | −0.0841 | −0.1531 | 0.1395 |

| Rachis type | 0.2758 | −0.242 | 0.2175 | 0.2157 | −0.2017 |

| Rachis length | −0.218 | −0.295 | 0.0131 | 0.0033 | −0.0512 |

| Lodicule number | −0.3512 | −0.2094 | 0.1482 | −0.0752 | 0.2034 |

| Lodicule shape | −0.0871 | −0.4006 | 0.2668 | −0.0211 | 0.2261 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.66771 | 3.7606 | 1.79297 | 1.29936 | 1.02581 |

| Contribution Rate % | 35.4% | 23.50% | 11.2% | 8.1% | 6.4% |

| Cumulative Contribution Rate % | 35.4% | 58.9% | 70.1% | 78.2% | 84.6% |

| Discriminant Function | Eigenvalue | Variance Contribution (%) | Cumulative Contribution (%) | Canonical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.421 | 69.5 | 69.5 | 0.891 |

| 2 | 0.996 | 20.2 | 89.7 | 0.709 |

| 3 | 0.362 | 7.3 | 97.0 | 0.534 |

| 4 | 0.128 | 2.6 | 99.6 | 0.347 |

| 5 | 0.018 | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.133 |

| 6 | 0.000 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.000 |

| Trait | Discriminant Function 1 | Discriminant Function 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Spikelet morphology | 0.502 | −0.179 |

| Spikelet length | −0.365 | 0.221 |

| Spikelet width | 0.394 | 0.087 |

| Lemma length | −0.428 | 0.193 |

| Pubescence on lemma margins | 0.376 | −0.152 |

| Palea length | −0.519 | 0.205 |

| Pubescence on palea margins | 0.473 | −0.251 |

| Ovary shape | −0.398 | 0.324 |

| Number of stamen | 0.479 | 0.163 |

| Number of lodicules | −0.358 | −0.210 |

| Lodicule shape | −0.412 | 0.285 |

| Actual Genus | Sample Size | Correctly Classified | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bambusa | 10 | 10 | 100.0 |

| Gigantochloa | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Pleioblastus | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Dendrocalamus | 4 | 3 | 75.0 |

| Phyllostachys | 3 | 3 | 100.0 |

| Schizostachyum | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Fargesia | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Total | 23 | 22 | 95.7 |

| Genus | Species | Flowering Time | Flowering Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bambusa | Bambusa sinospinosa McClure | 2010.4 | Bamboo Garden, Kunming Expo Park, Yunnan Province |

| Bambusa ventricosa McClure | 2012.4 | Bamboo Garden, Kunming Expo Park, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa eutuldoides var. Viridivittata (W. T. Lin) L. C. Chia | 2013.8 | Mengla County, Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa textilis McClure | 2013.8 | Mengla County, Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa tuldoides Munro | 2023.7 | Rare Bamboo Garden at Southwest Forestry University in Kunming City, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa rigida Keng & P. C. Keng | 2017.4 | Rare Bamboo Garden at Southwest Forestry University in Kunming City, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa rutila McClure | 2017.5 | Rare Bamboo Garden at Southwest Forestry University in Kunming City, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa emeiensis L. C. Chia & H. L. Fung | 2012.9 | Rare Bamboo Garden at Southwest Forestry University in Kunming City, Yunnan Province | |

| Bambusa cerosissima McClure | 2022.10 | Chishui County Bamboo Sea National Forest Park, Guizhou Province | |

| Bambusa intermedia J. R. Xue & T. P. Yi | 2014.5 | Yunnan Kunming World Horticultural Expo Bamboo Garden | |

| Gigantochloa | Gigantochloa sp. 1 (SWFC0072425) | 2020.5 | Mangshi, Dehong Prefecture, Yunnan Province |

| Gigantochloa sp. 2 (SWFC0072426) | 2020.5 | Mangshi, Dehong Prefecture, Yunnan Province | |

| Pleioblastus | Pleioblastus fortunei (Van Houtte ex Munro) Nakai | 2015.7 | Simao District, Pu’er City, Yunnan Province |

| Dendrocalamus | Dendrocalamus sinicus L. C. Chia & J. L. Sun | 2014.7 | Cangyuan Wa Autonomous County, Yunnan Province |

| Dendrocalamus giganteus Wall. ex Munro | 2012.10 | Mojiang County, Pu’er City, Yunnan Province | |

| Dendrocalamus fugongensis J. R. Xue & D. Z. Li | 2023.1 | Fugong County, Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province | |

| Dendrocalamus hamiltonii Nees & Arn. ex Munro | 2015.7 | Mengla County, Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province | |

| Phyllostachys | Phyllostachys sulphurea (Carrière) Riviere & C. Rivière | 2013.5 | Panlong District, Kunming City, Yunnan Province |

| Phyllostachys glauca McClure | 2018.7 | Panlong District, Kunming City, Yunnan Province | |

| Phyllostachys nigra (Lodd. ex Lindl.) Munro | 2021.8 | Southwest Forestry University in Kunming City, Yunnan Province | |

| Schizostachyum | Schizostachyum brachycladum (Kurz) Kurz | 2017.10 | Simao District, Pu’er City, Yunnan Province |

| Fargesia | Fargesia yuanjiangensis J. R. Xue & T. P. Yi | 2018.7 | Rare Bamboo Garden at Southwest Forestry University in Kunming City, Yunnan Province |

| Fargesia fungosa T. P. Yi | 2014.4 | Yunnan Kunming World Horticultural Expo Bamboo Garden |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, S. Morphological Characteristics of Floral Organs and Their Taxonomic Significance in 23 Species of Bamboo from Southwest China. Plants 2025, 14, 3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243751

Wang X, Liu J, Zhao C, Wang S. Morphological Characteristics of Floral Organs and Their Taxonomic Significance in 23 Species of Bamboo from Southwest China. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243751

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xingyu, Jiaxin Liu, Chongsheng Zhao, and Shuguang Wang. 2025. "Morphological Characteristics of Floral Organs and Their Taxonomic Significance in 23 Species of Bamboo from Southwest China" Plants 14, no. 24: 3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243751

APA StyleWang, X., Liu, J., Zhao, C., & Wang, S. (2025). Morphological Characteristics of Floral Organs and Their Taxonomic Significance in 23 Species of Bamboo from Southwest China. Plants, 14(24), 3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243751