Niche-Driven Bacterial Assembly Versus Weak Geographical Divergence of Fungi in the Rhizosheath of Desert Plant Leymus racemosus (Lam.) Tzvel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Soil Properties

2.2. Microbial Community Overview

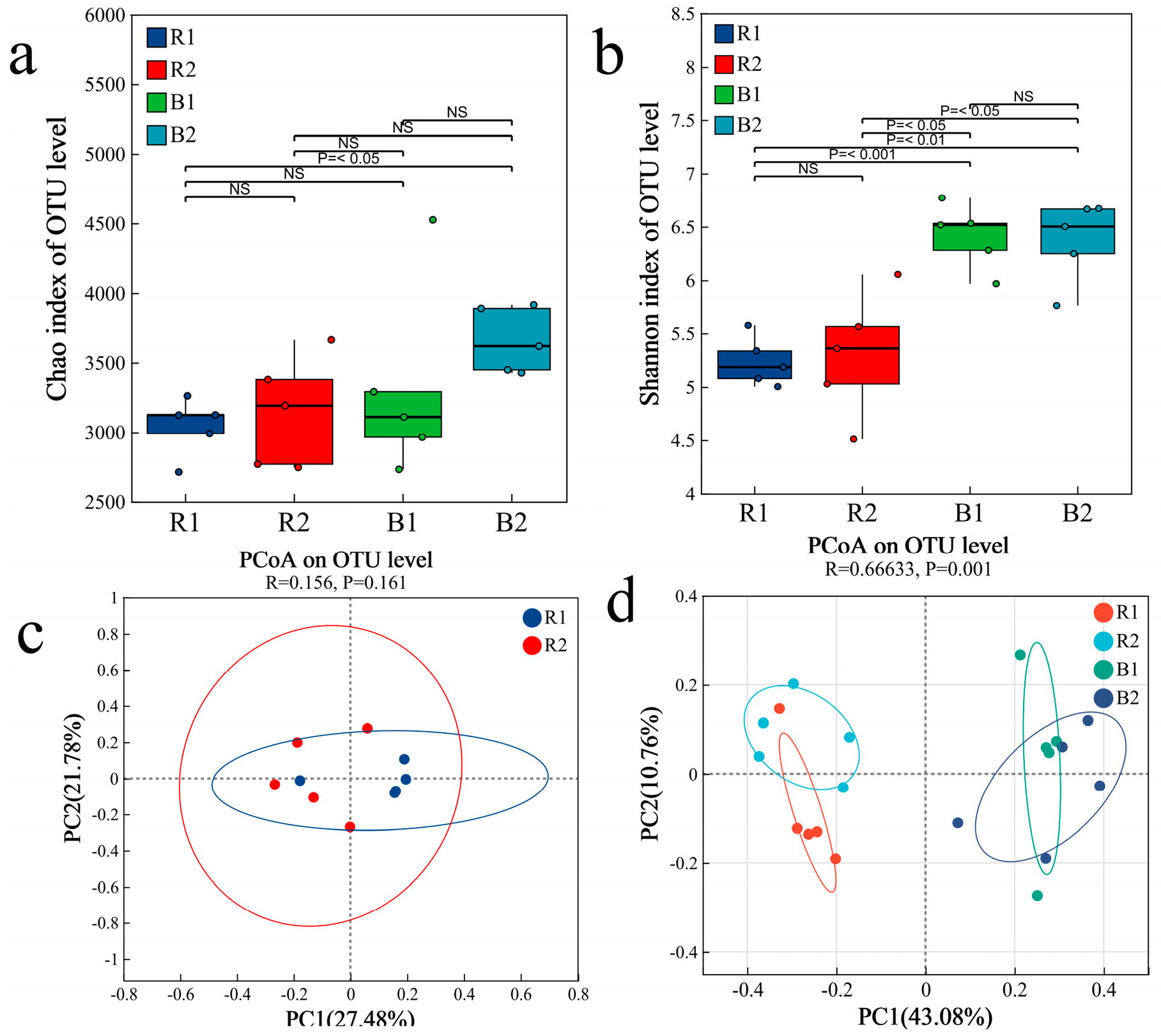

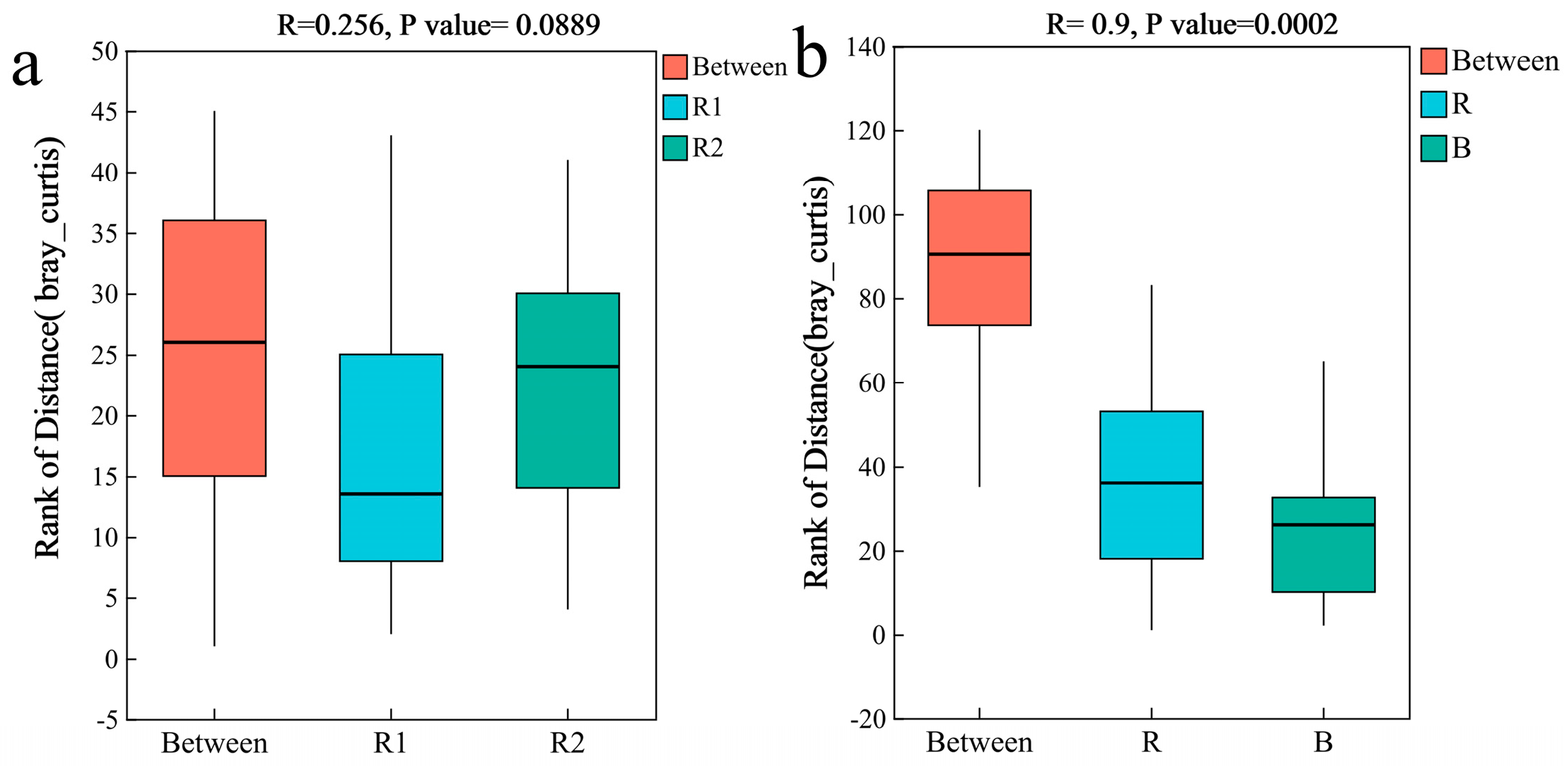

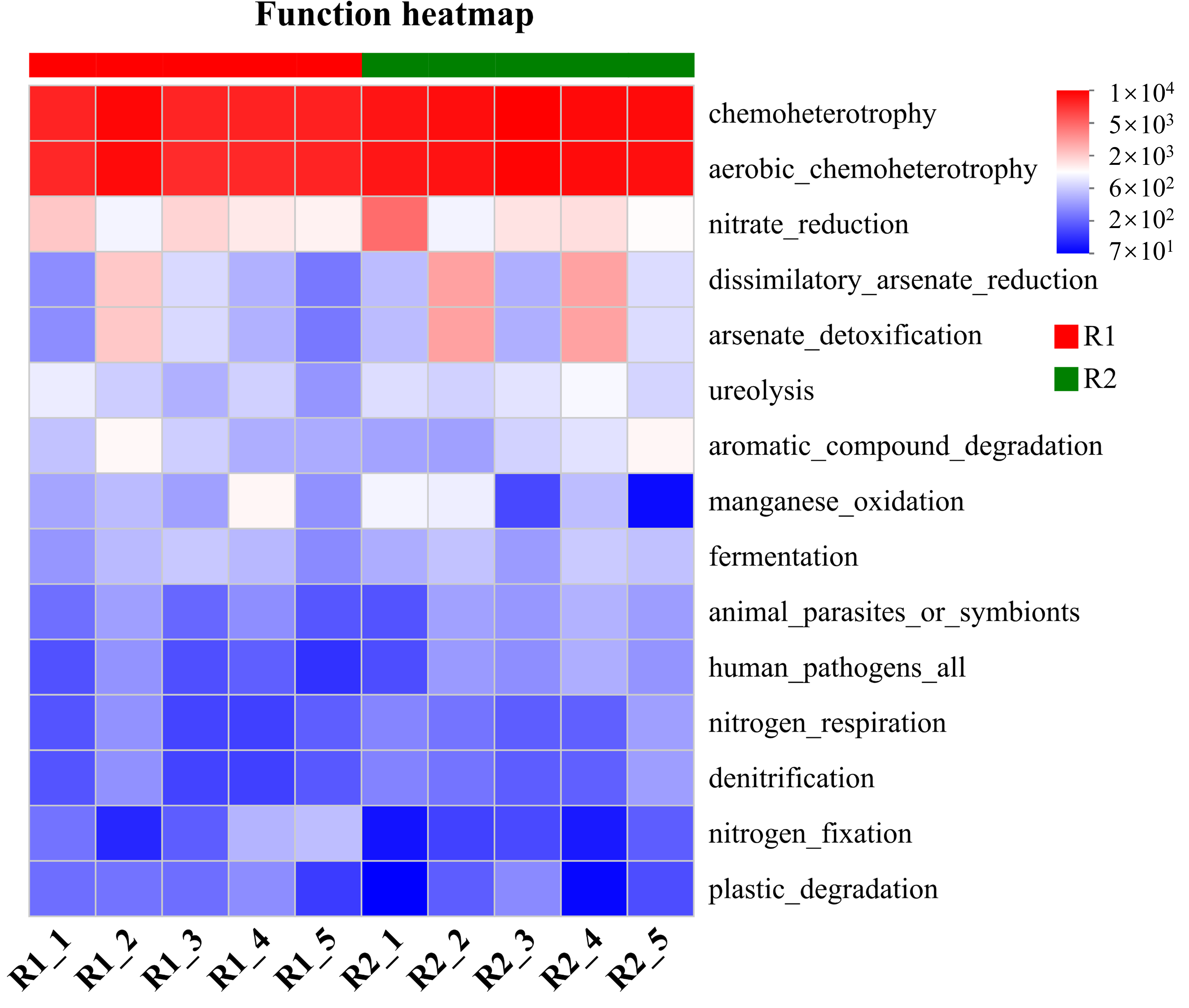

2.3. Characteristics of the Bacterial Community

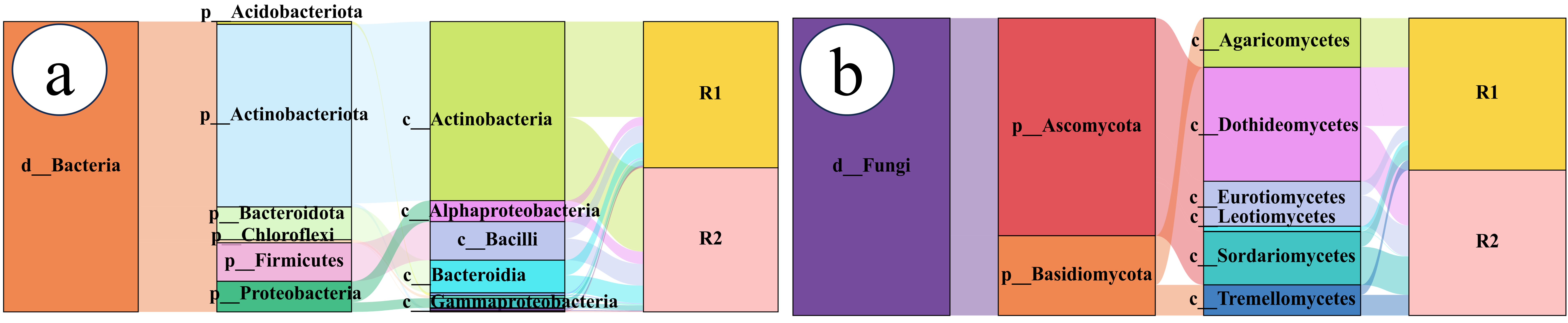

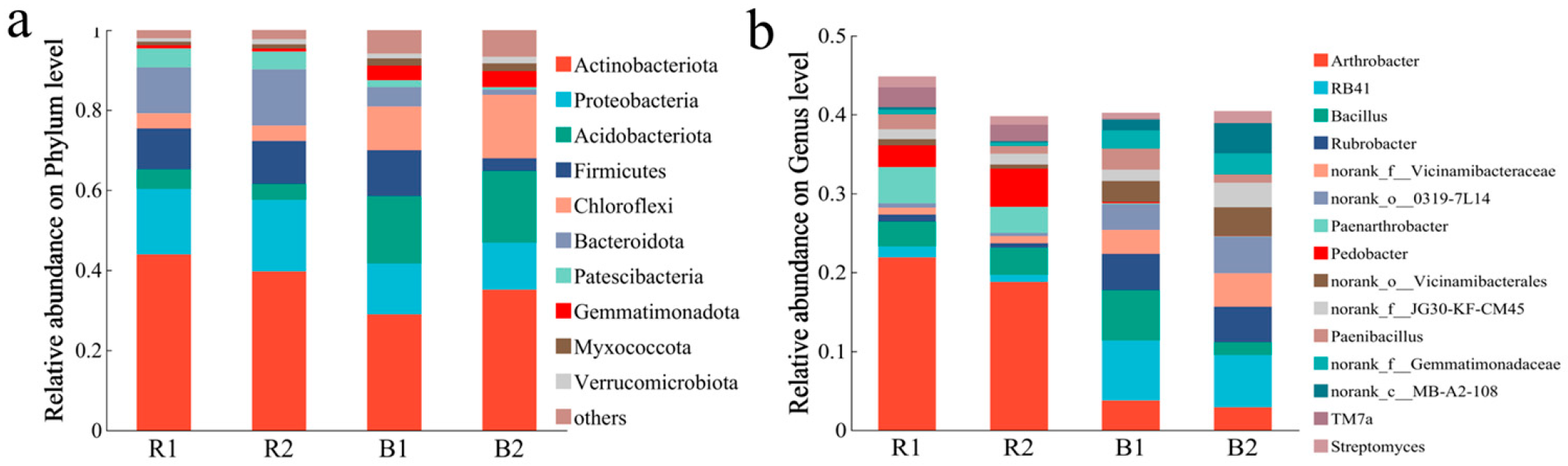

2.3.1. Bacterial Community Composition

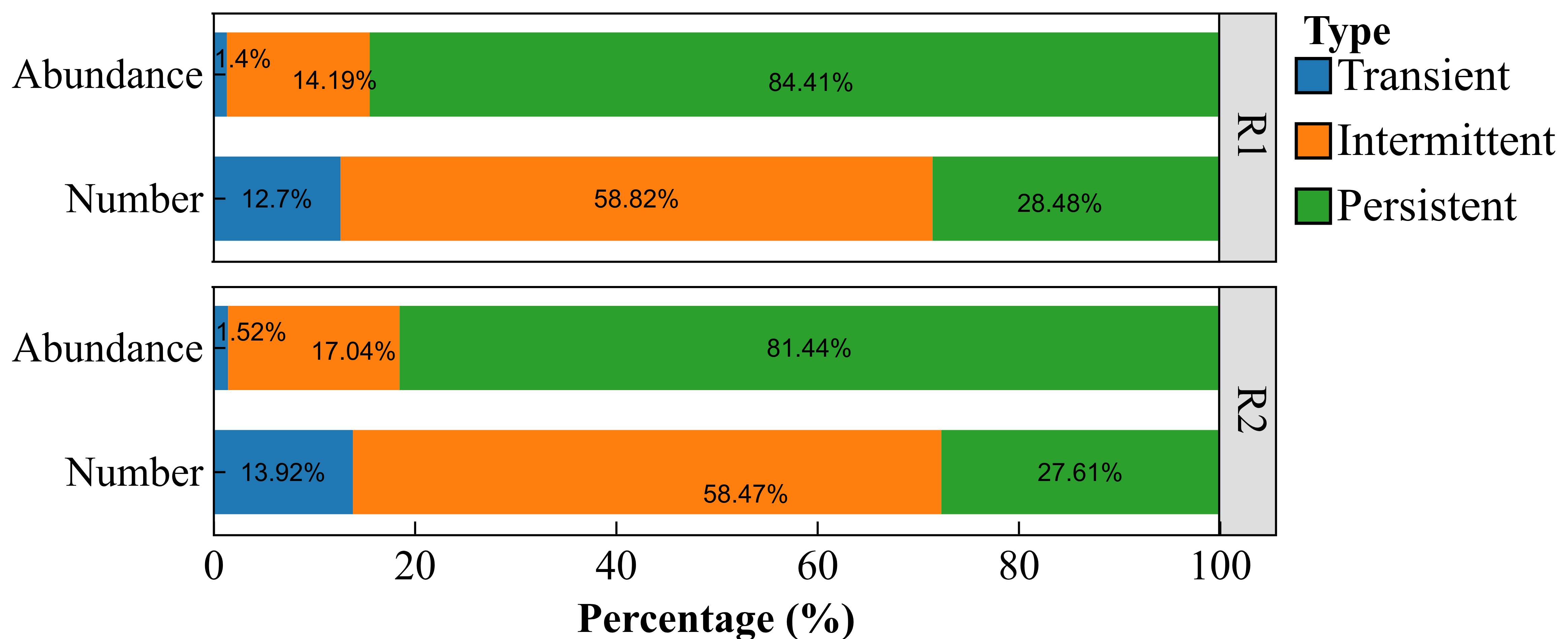

2.3.2. Core Rhizosheath-Specific Bacterial Taxa

2.4. Fungal Community Characteristics

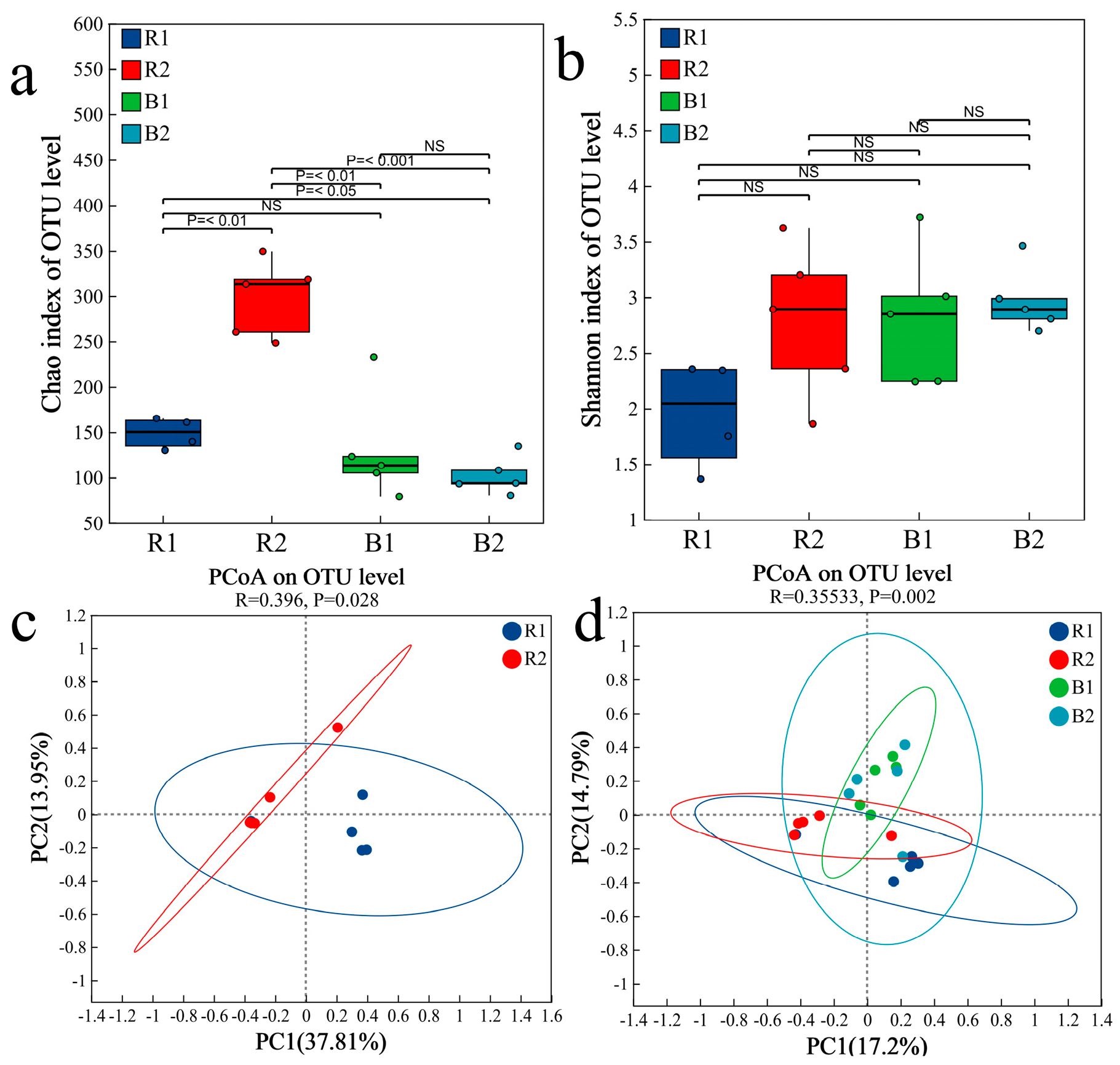

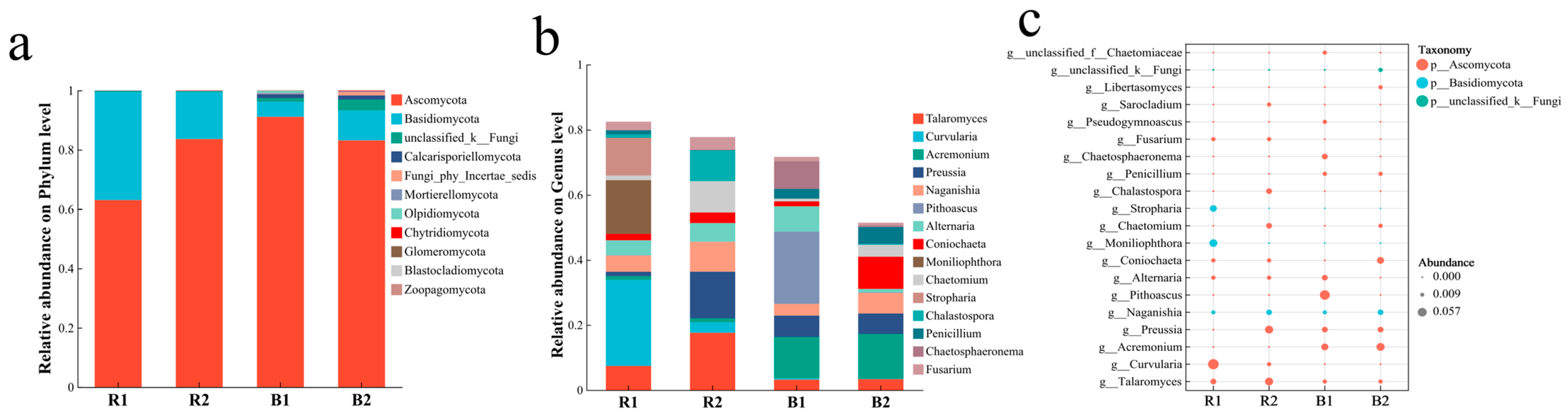

2.4.1. Fungal Community Composition

2.4.2. Analysis of Differences in Fungal Communities

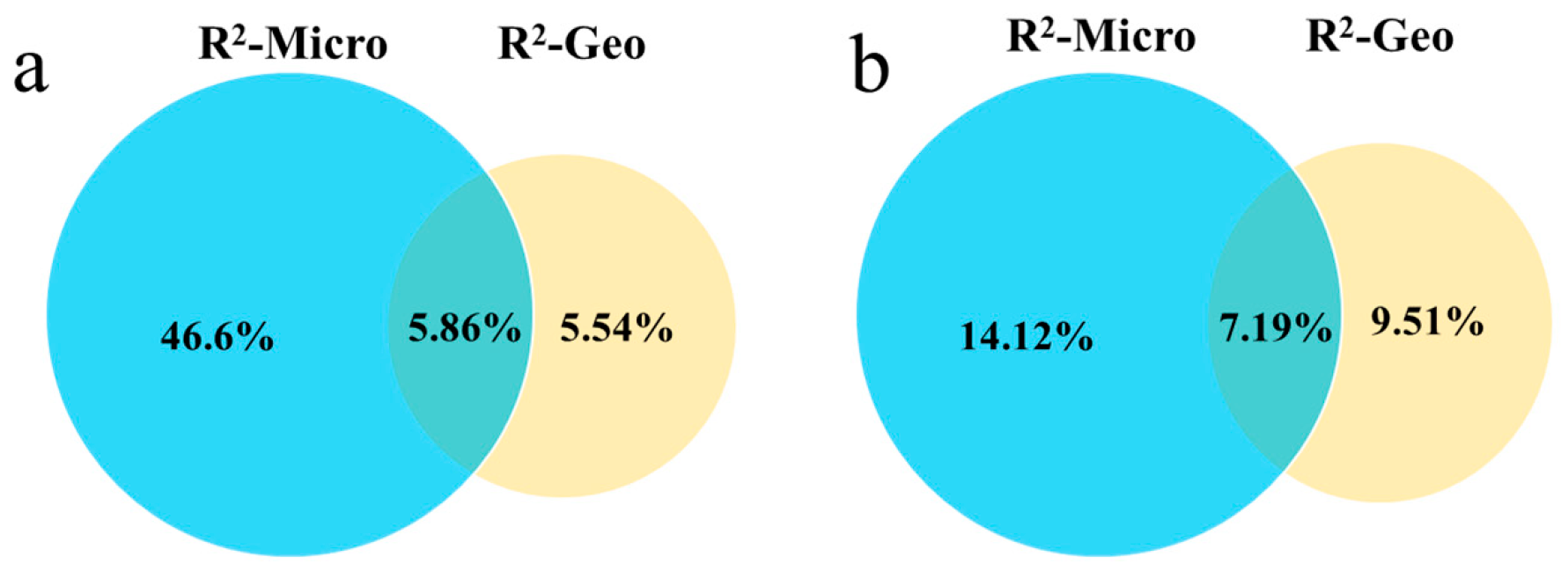

2.5. Decomposition of Multifactorial Explanatory Power

3. Discussion

3.1. The Strong Microenvironment Selection in the Rhizosheath Bacterial Community of L. racemosus

3.2. The Weak Influence of Geographical Distance on Rhizosheath Fungal Communities

3.3. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

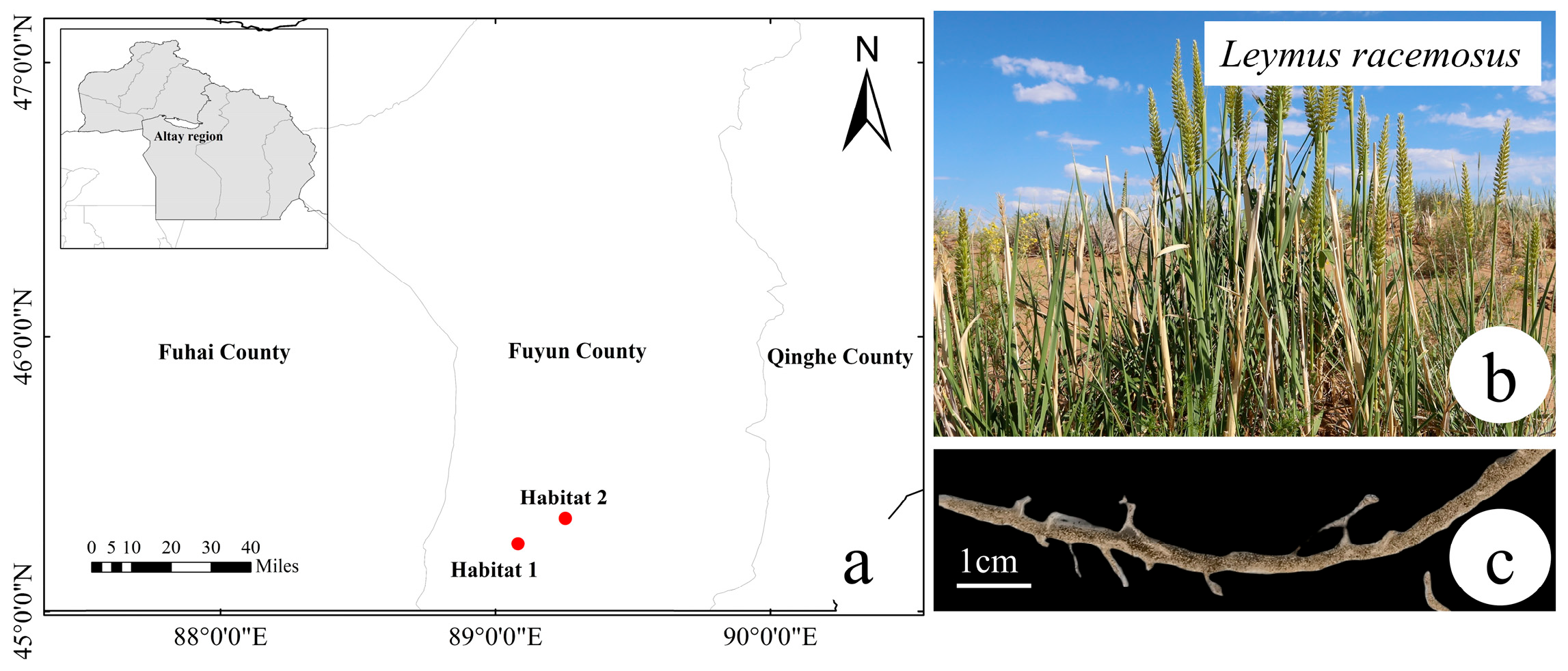

4.1. Study Area and Sampling

4.2. Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties

4.3. DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

4.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Hong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, N.; Jiang, S.; Yao, Z.; Zhu, M.; Ding, J.; Li, C.; Xu, W.; et al. Rhizosheath Formation and Its Role in Plant Adaptation to Abiotic Stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addesso, R.; Sofo, A.; Amato, M. Rhizosheath: Roles, Formation Processes and Investigation Methods. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, R.; Fusi, M.; Ramond, J.; Ramond, J.; Van Goethem, M.; Seferji, K.; Maggs-Kölling, G.; Cowan, D.; Daffonchio, D. The plant rhizosheath-root niche is an edaphic “mini-oasis” in hyperarid deserts with enhanced microbial competition. ISME Commun. 2022, 2, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Basirat, M.; Mousavi, S.; Abbaszadeh, S.; Ebrahimi, M.; Zarebanadkouki, M. The rhizosheath: A potential root trait helping plants to tolerate drought stress. Plant Soil 2019, 445, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, M.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M.; Aslam, M.; Kang, J.; Hu, T.; Liu, T. Trends in rhizosheath research: Formation, functions and methods. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 237, 106217. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Liao, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, P.; Cao, Y.; Fang, J.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; Sun, L. Auxin-producing bacteria promote barley rhizosheath formation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, G. The distribution of abundance in neutral communities. Am. Nat. 2000, 155, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Jia, T. Distribution Patterns and Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities at Different Spatiotemporal Scales: A Review. Soil 2024, 56, 689–696. [Google Scholar]

- Gravel, D.; Canham, C.; Beaudet, M.; Messier, C. Reconciling niche and neutrality: The continuum hypothesis. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewin, V. Beyond neutrality-ecology finds its niche. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, P.; Gao, G.; Ren, Y.; Ding, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Intra-annual variation of root-associated fungi of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica: The role of climate and implications for host phenology. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 176, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papke, R.; Ramsing, N.; Bateson, M.; Ward, D. Geographical isolation in hot spring cyanobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B.; Liu, W.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y. The root microbiome:Community assembly and its contributions to plant fitness. Acta Bot. Sin. 2022, 64, 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Trivedi, P.; Wang, N. The structure and function of the global citrus rhizosphere microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosindell, J.; Hubbell, S.; Etienne, R. The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.; Tringe, S.; Sa, T.; Singh, B. Plant-microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Montoya, L.; Xu, L.; Madera, M.; Hollingsworth, J.; Purdom, E.; Singan, V.; Vogel, J.; Hutmacher, R.; Dahlberg, J.; et al. Fungal community assembly in drought-stressed sorghum shows stochasticity, selection, and universal ecological dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, J.; Myers, J. Disentangling the Importance of Ecological Niches from Stochastic Processes Across Scales. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 2351–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Martiny, J.B.H.; Allison, S.D. Effects of Dispersal and Selection on Stochastic Assembly in Microbial Communities. ISME J. 2017, 11, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C.; Van d, G.; Burns, C.; Mcnamara, N.; Bending, G. Temporally variable geographical distance effects contribute to the assembly of root-associated fungal communities. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, X.; Wang, M.; Zeng, H.; Wang, J. Rhizosheath: Distinct features and environmental functions. Geoderma 2023, 435, 116500. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdish, I.; Chobotarov, A. Functioning of microorganisms in the rhizosphere of plants. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2024, 14, e10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, T.; Yang, Y. Similarities and differences in the rhizosphere biota among different ephemeral desert plants in Gurbantünggüt Desert. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alswat, A.; Jalal, R.; Shami, A.; Majeed, M.; Alsaedi, Z.; Baz, L. Investigating the metagenomics of the bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of the desert plant Senna italica and their role as plant growth promoting factors. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2023, 51, 13053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, Y.; Hauschner, H.; Adams, J.; Doniger, T.; Sherman, C. Influence of Desert Microhabitats on the Abundance and Composition of Live and Dead Soil Bacterial Communities. Open J. Ecol. 2025, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; He, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Lv, X.; Pu, X.; Zhuang, L. Community distribution of rhizosphere and endophytic bacteria of ephemeral plants in desert-oasis ecotone and analysis of environmental driving factors. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, Z.; Al-Ashhab, A.; Gatica, J.; Gafny, R.; Avraham, S.; Minz, D.; Gillor, O.; Jurkevitch, E. Spatial and Temporal Biogeography of Soil Microbial Communities in Arid and Semiarid Regions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Robert, C.; Selma, C.; Xi, Z.; Meng, Y.; Beibei, L.; Manzo, D.; Chervet, N.; Steinger, T.; van der Heijden, M.; et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bais, H.; Weir, T.; Perry, L.; Gilroy, S.; Vivanco, J. The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Li, Y.-h.; Xu, W.-h.; Chen, W.-j.; Hu, Y.-l.; Wang, Z.-g. Different genotypes regulate the microbial community structure in the soybean rhizosphere. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 22, 585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Nannipieri, P.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.; Landi, L.; Valori, F. Effects of Root Exudates in Microbial Diversity and Activity in Rhizosphere Soils. Soil Biol. 2008, 15, 339–365. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, N.; Xiao, M.; Li, X.; Yao, M. Different assembly mechanisms between prokaryotic and fungal communities in grassland plants and soil. Plant Soil 2024, 505, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Lan, G. Geographical Differences Weaken the Convergence Effect of the Rhizosphere Bacteria of Rubber Trees. Forests 2024, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, R.; Fusi, M.; Mosqueira, M.; Booth, J.; Rossi, F.; Cardinale, M.; Michoud, G.; Rolli, E.; Mugnai, G.; Vergani, L. Rhizosheath–root system changes exopolysaccharide content but stabilizes bacterial community across contrasting seasons in a desert environment. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2022, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Lv, G. Root exudates facilitate the regulation of soil microbial community function in the genus Haloxylon. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1461893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Ge, A.; Qi, S.; Guan, Y.; Wang, R.; Yu, N.; Wang, E. Root exudates and microbial metabolites: Signals and nutrients in plant-microbe interactions. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 2290–2320. [Google Scholar]

- Woniak, M.; Gazka, A. The rhizosphere microbiome and its beneficial effects on plants–current knowledge and perspectives. Postep. Mikrobiol. 2019, 58, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.; Soleymani, A. The Roles of Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)-Based Biostimulants for Agricultural Production Systems. Plants 2024, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- András, S.; Viktor, K.; Balázs, Á.; Erika, L.; László, V.; Babett, G. Bioactive Potential of Actinobacteria Strains Isolated from the Rhizosphere of Lavender, Lemon Balm, and Oregano. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R.; Cheng, Z.; Czarny, J.; Duan, J. Promotion of plant growth by ACC deaminase-producing soil bacteria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2007, 119, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.A.P. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria enhances germination and bioactive compound in cucumber seedlings under saline stress. Ecosistemas Recur. Agropecu. 2025, 12, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Aviles-Garcia, M.; Flores-Cortez, I.; Hernández-Soberano, C.; Christian; Santoyo, G.; Valencia-Cantero, E. La rizobacteria promotora del crecimiento vegetal Arthrobacter agilis UMCV2 coloniza endofíticamente a Medicago truncatula. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2016, 48, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazard, C.; Gosling, P.; Van Der Gast, C.J.; Gosling, P.; Gast, C.; Bending, G. The role of local environment and geographical distance in determining community composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi at the landscape scale. ISME J. 2013, 7, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. Archaea show different geographical distribution patterns compared to bacteria and fungi in Arctic marine sediments. mLife 2025, 4, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Song, X.; Yu, S.; Jiang, X. Altitudinal variation in rhizosphere microbial communities of the endangered plant Lilium tsingtauense and the environmental factors driving this variation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00966-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obase, K.; Kitagami, Y.; Tanikawa, T.; Chen, C.; Matsuda, Y. Fungi and bacteria in the rhizosphere of Cryptomeria japonica exhibited different community assembly patterns at regional scales in East Asia. Hizosphere 2023, 28, 100807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, D.; Abbott, L.; Robson, A. The effect of soil disturbance on vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soils from different vegetation types. New Phytol. 2010, 118, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos-Espeleta, J.; Marin-Jaramillo, J.; Schmidt, S.; Sommers, P.; Bradley, J.; Orsi, W. Principal role of fungi in soil carbon stabilization during early pedogenesis in the high Arctic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scervino, J.; Mesa, M.; Mónica, I.; Recchi, M.; Sarmiento, N.; Godeas, A. Soil fungal isolates produce different organic acid patterns involved in phosphate salts solubilization. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trklmez, A.; Eren, A.; Zer, G.; Derv, S. The Effect of Talaromyces funiculosus ST976 Isolated from Pistacia vera Rhizosphere on Phosphorus Solubility in Soil Samples with Different Physicochemical Properties. J. Agric. Nat./Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım Doğa Derg. 2022, 25, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantasorn, A.; Oiuphisittraiwat, T.; Wangsawang, S.; Cha-Aim, K. Application of ready-to-use dry-powder formulation of Talaromyces flavus Bodhi001 against rice brown leaf spot disease and to promote the yield components of rice in saline-alkaline soils. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2025, 172, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharsini, P.; Muthukumar, T. The root endophytic fungus Curvularia geniculata from Parthenium hysterophorus roots improves plant growth through phosphate solubilization and phytohormone production. Fungal Ecol. 2017, 27, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, N.; Bellora Nicolás Sajeet, H.; Sajeet, H.; Hui, S.; Chris, D.; Kerrie, B.; Grigoriev, I.; Diego, L.; Connell, L.; Martín, M. Unique genomic traits for cold adaptation in Naganishia vishniacii, a polyextremophile yeast isolated from Antarctica. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 21, foaa056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiersch, G.; Rajasärkkä, J.; Ullrich, R.; Tuomela, M.; Hofrichter, M.; Virta, M.; Hatakka, A.; Steffen, K. Fate of bisphenol A during treatment with the litter-decomposing fungi Stropharia rugosoannulata and Stropharia coronilla. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soytong, K.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kukongviriyapa, V.; Isobe, M. Application of Chaetomium species (Ketomium(Ketomium®) as a new broad spectrum biological fungicide for plant disease control: A review article. Fungal Divers. 2001, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R.; Tewari, A.; Srivastava, K.; Singh, D. Role of antibiosis in the biological control of spot blotch (Cochliobolus sativus) of wheat by Chaetomium globosum. Mycopathologia 2004, 157, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, J.; Ryan, M.; Siddique, K.; Simpson, R. Unwrapping the rhizosheath. Plant Soil 2017, 418, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, H.; Xu, F.; Ding, Y.; Xu, W. Root-Bacteria Associations Boost Rhizosheath Formation in Moderately Dry Soil through Ethylene Responses. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, N.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Yu, G.; Zhang, W.; Jobbágy, E. Soil inorganic carbon storage pattern in China. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 2380–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2004. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Claesson, M.; Wang, Q.; O’sullivan, O.; Greene-Diniz, R.; Cole, J.; Ross, R.; O’Toole, P. Comparison of two next-generation sequencing technologies for resolving highly complex microbiota composition using tandem variable 16S rRNA gene regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes-application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schloss, P.; Westcott Ryabin, S.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.; Lesniewski, A.; Oakley, B.; Parks, D.; Robinson, C. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, L.; Han, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, W.; Gao, H.; Huang, H. Majorbio Cloud 2024: Update single-cell and multiomics workflows. Imeta 2024, 3, e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Name | B1 | B2 | Sample Name | B1 | B2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 8.17 ± 0.25 a | 8.23 ± 0.23 a | WK (mg/kg) | 4.18 ± 1.77 a | 6.54 ± 1.23 a |

| EC | 47.37 ± 4.32 a | 50.17 ± 6.43 a | WNa (mg/kg) | 23.66 ± 8.72 a | 17.93 ± 3.05 a |

| TOC (g/kg) | 1.03 ± 0.22 a | 0.78 ± 0.106 a | WCa (mg/kg) | 30.01 ± 5.15 a | 25.59 ± 6.05 a |

| TN (g/kg) | 0.06 ± 0.006 a | 0.05 ± 0.006 a | SO42− (mg/kg) | 15.45 ± 4.65 a | 21.32 ± 4.73 a |

| TP (g/kg) | 0.038 ± 0.007 a | 0.037 ± 0.005 a | Cl− (mg/kg) | 12.92 ± 1.45 a | 9.84 ± 2.57 a |

| Bacterial | Fungal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Pseudo-F | R2 | p | Pseudo-F | R2 | p |

| Geo | 0.822 | 5.54% | 0.518 | 1.472 | 9.51% | 0.079 |

| Micro | 12.217 | 46.6% | 0.001 | 2.321 | 14.2% | 0.004 |

| Geo × Micro | 5.534 | 58.0% | 0.001 | 1.787 | 30.9% | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J. Niche-Driven Bacterial Assembly Versus Weak Geographical Divergence of Fungi in the Rhizosheath of Desert Plant Leymus racemosus (Lam.) Tzvel. Plants 2025, 14, 3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243747

Sun Y, Tang J, Zhou X, Liu J. Niche-Driven Bacterial Assembly Versus Weak Geographical Divergence of Fungi in the Rhizosheath of Desert Plant Leymus racemosus (Lam.) Tzvel. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243747

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yufang, Jinfeng Tang, Xiaohao Zhou, and Jun Liu. 2025. "Niche-Driven Bacterial Assembly Versus Weak Geographical Divergence of Fungi in the Rhizosheath of Desert Plant Leymus racemosus (Lam.) Tzvel" Plants 14, no. 24: 3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243747

APA StyleSun, Y., Tang, J., Zhou, X., & Liu, J. (2025). Niche-Driven Bacterial Assembly Versus Weak Geographical Divergence of Fungi in the Rhizosheath of Desert Plant Leymus racemosus (Lam.) Tzvel. Plants, 14(24), 3747. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243747