Stand Density Drives Soil Microbial Community Structure in Response to Nutrient Availability in Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilger Plantations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

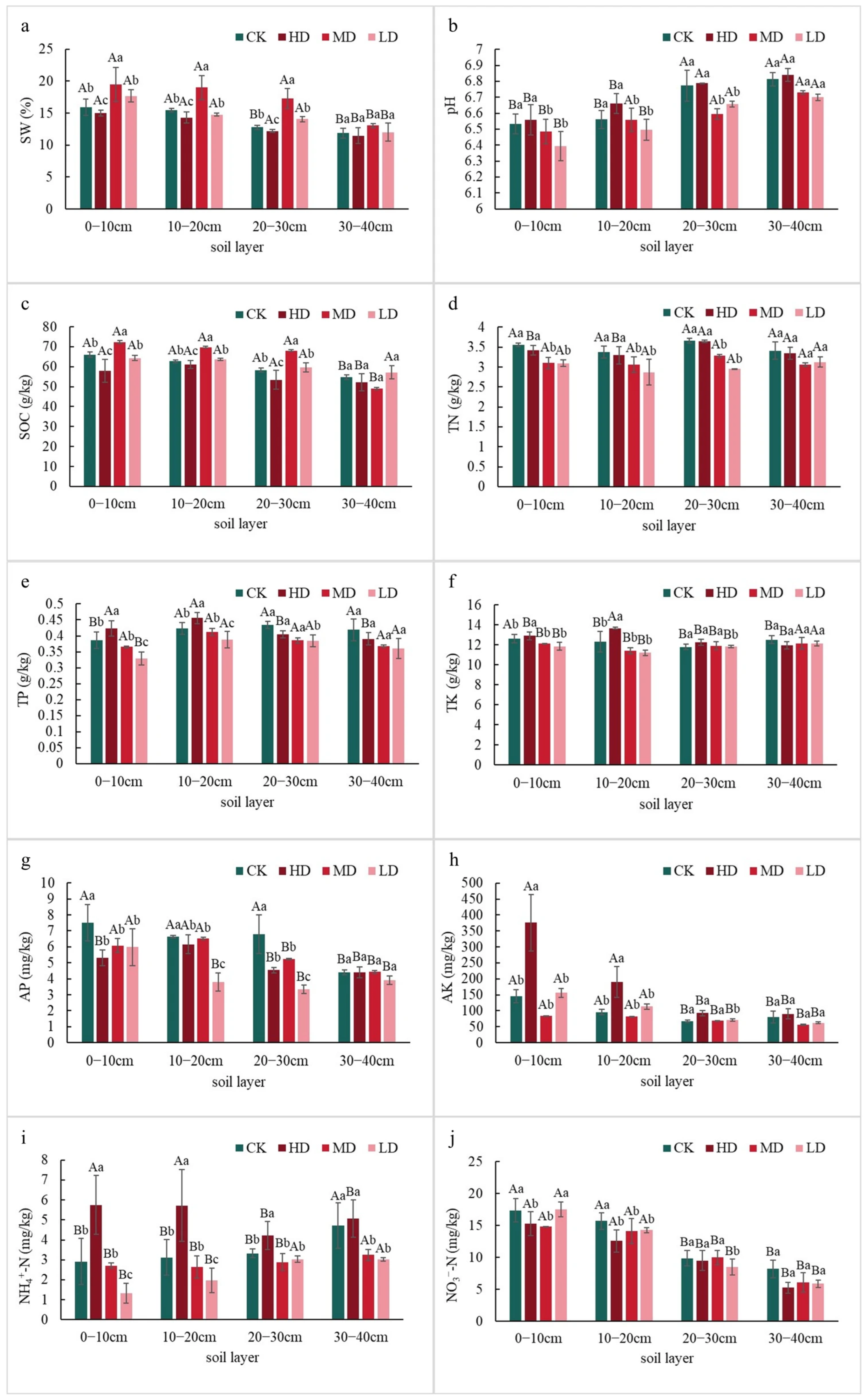

2.1. Differences in Soil Physicochemical Properties Among a Larix principis-rupprechtii Plantations with Different Stand Densities

2.1.1. Differences in Soil Nutrient Content

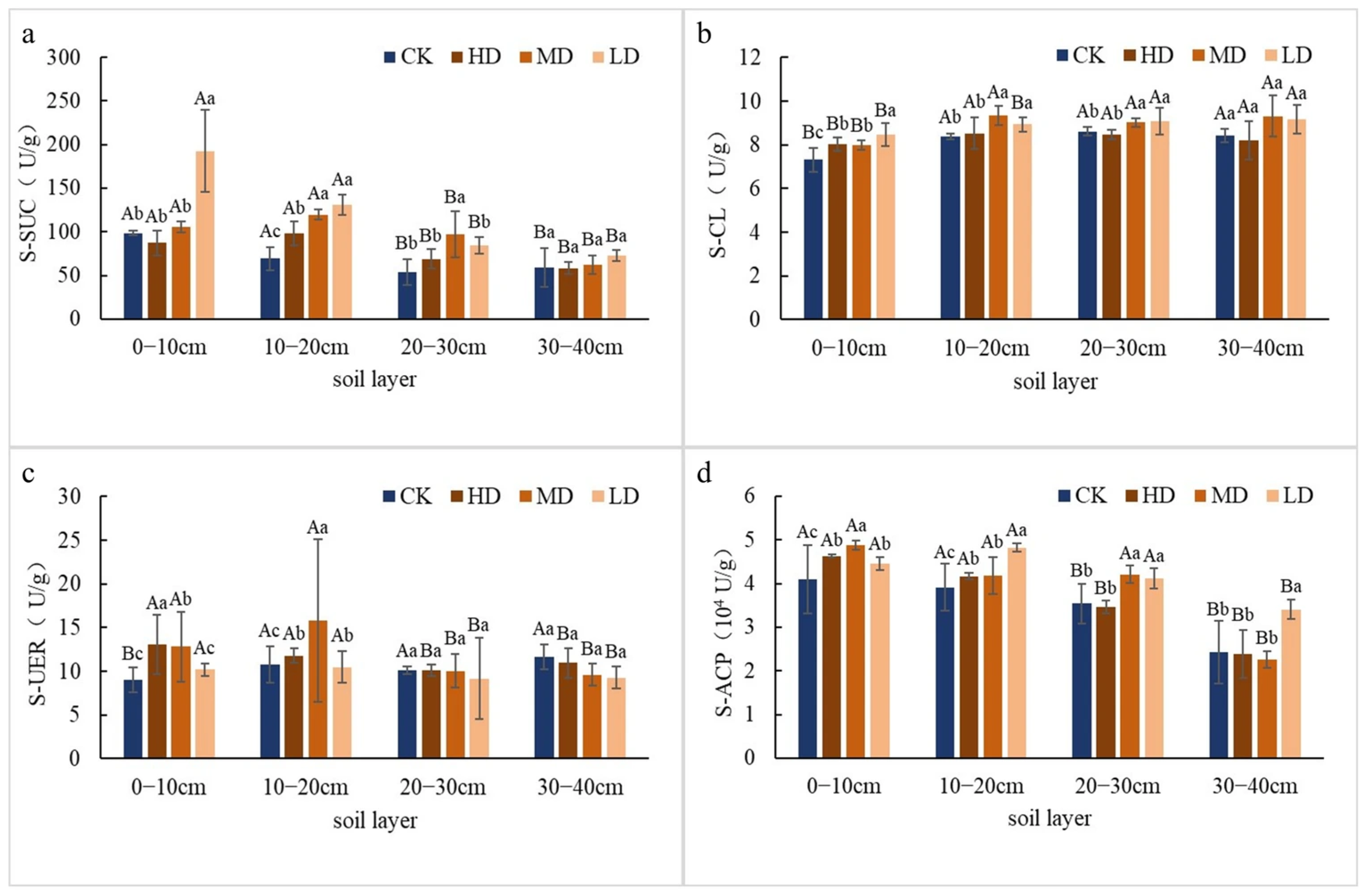

2.1.2. Differences in Soil Enzyme Activity

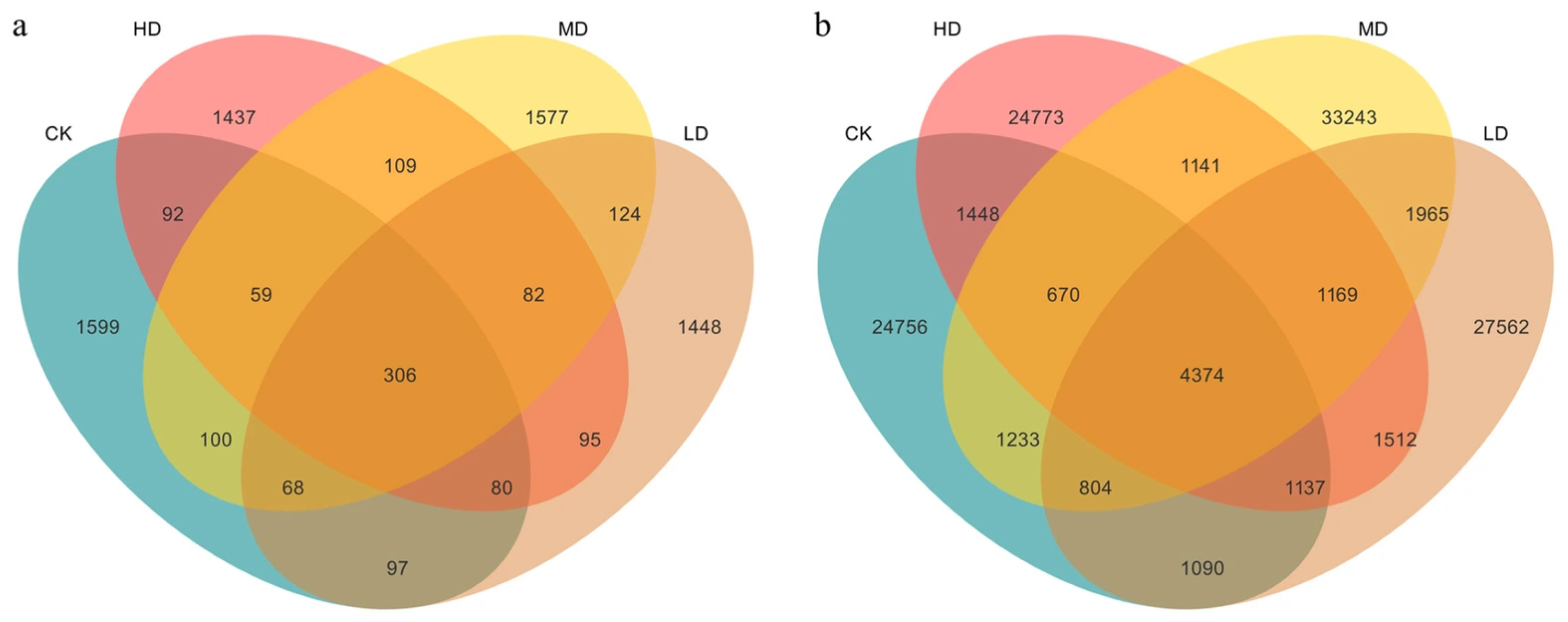

2.2. Soil Microbial Community Structure in Larix principis-rupprechtii Plantations Under Different Stand Densities

2.2.1. Micro Differences in the Species-Level Structure of Soil Microorganisms

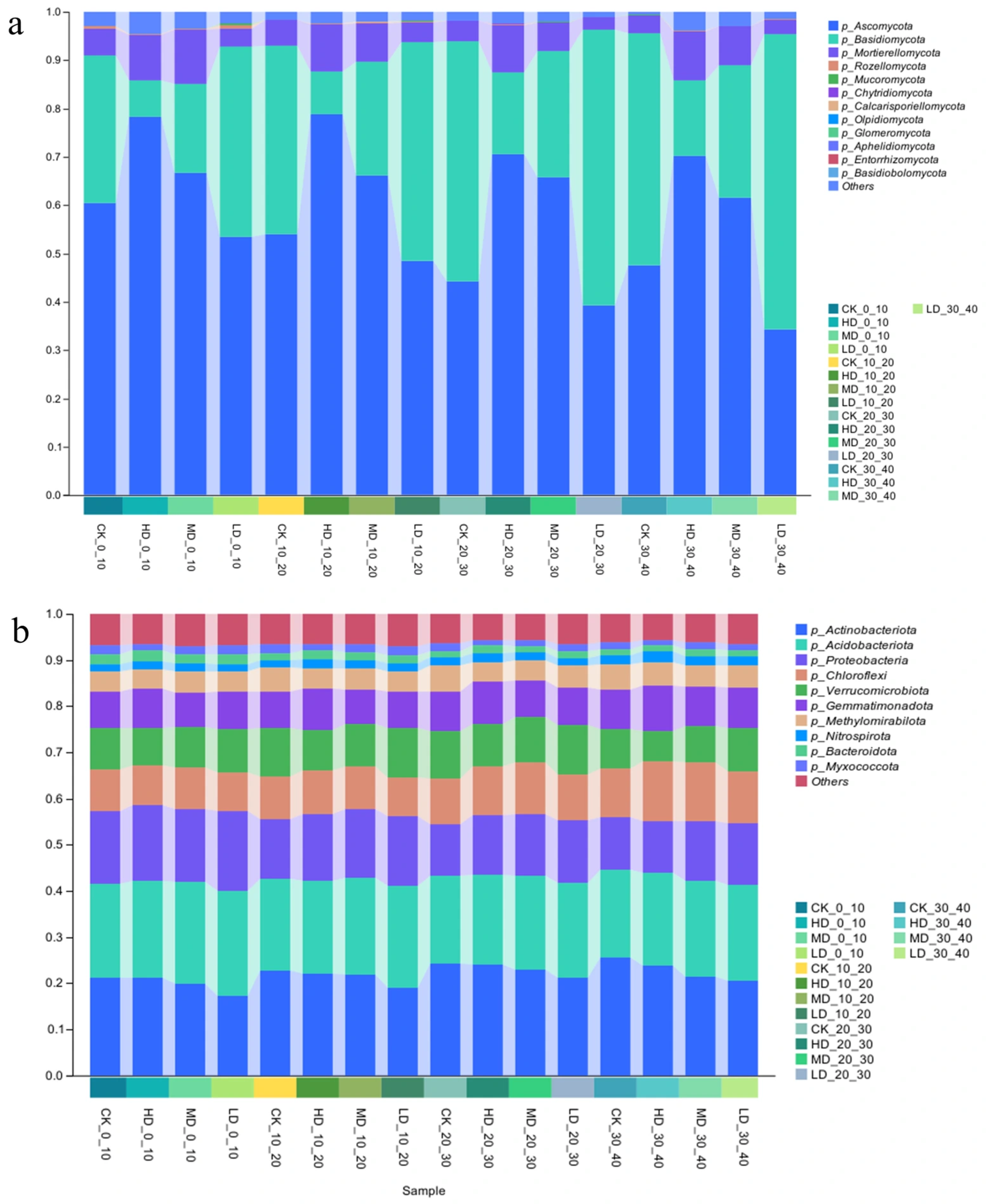

2.2.2. Differences in the Phylum-Level Structure of Soil Microorganisms

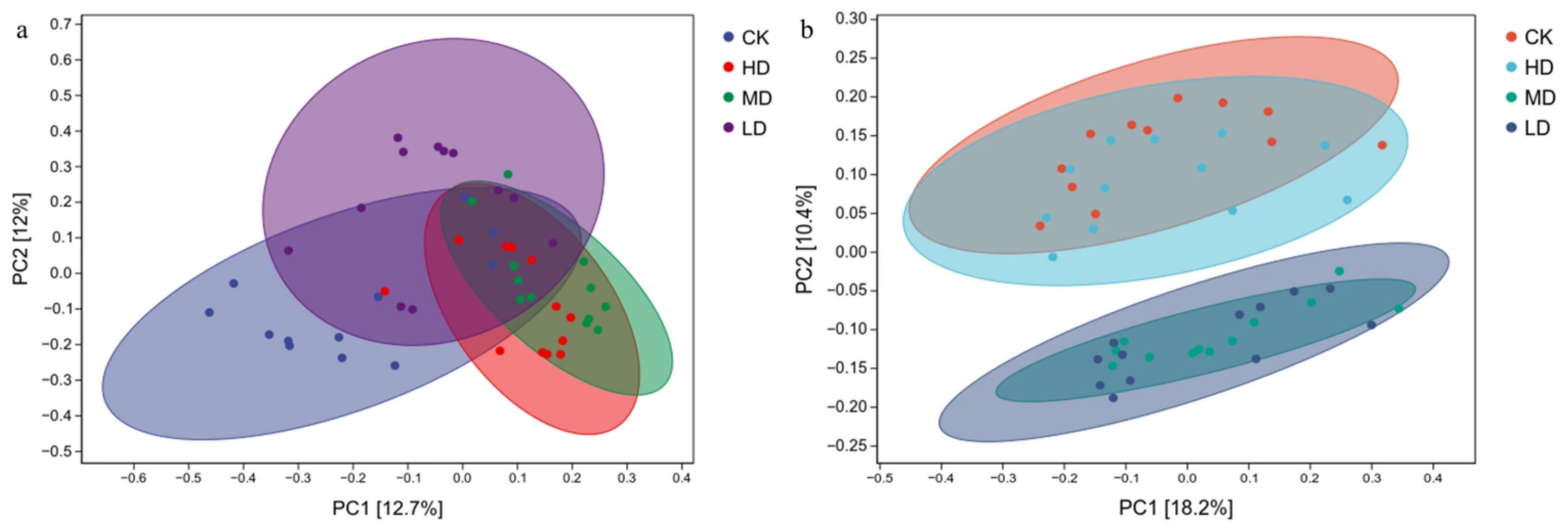

2.3. Soil Microbial Diversity Analysis in Larix principis-rupprechtii Plantations Under Different Stand Densities

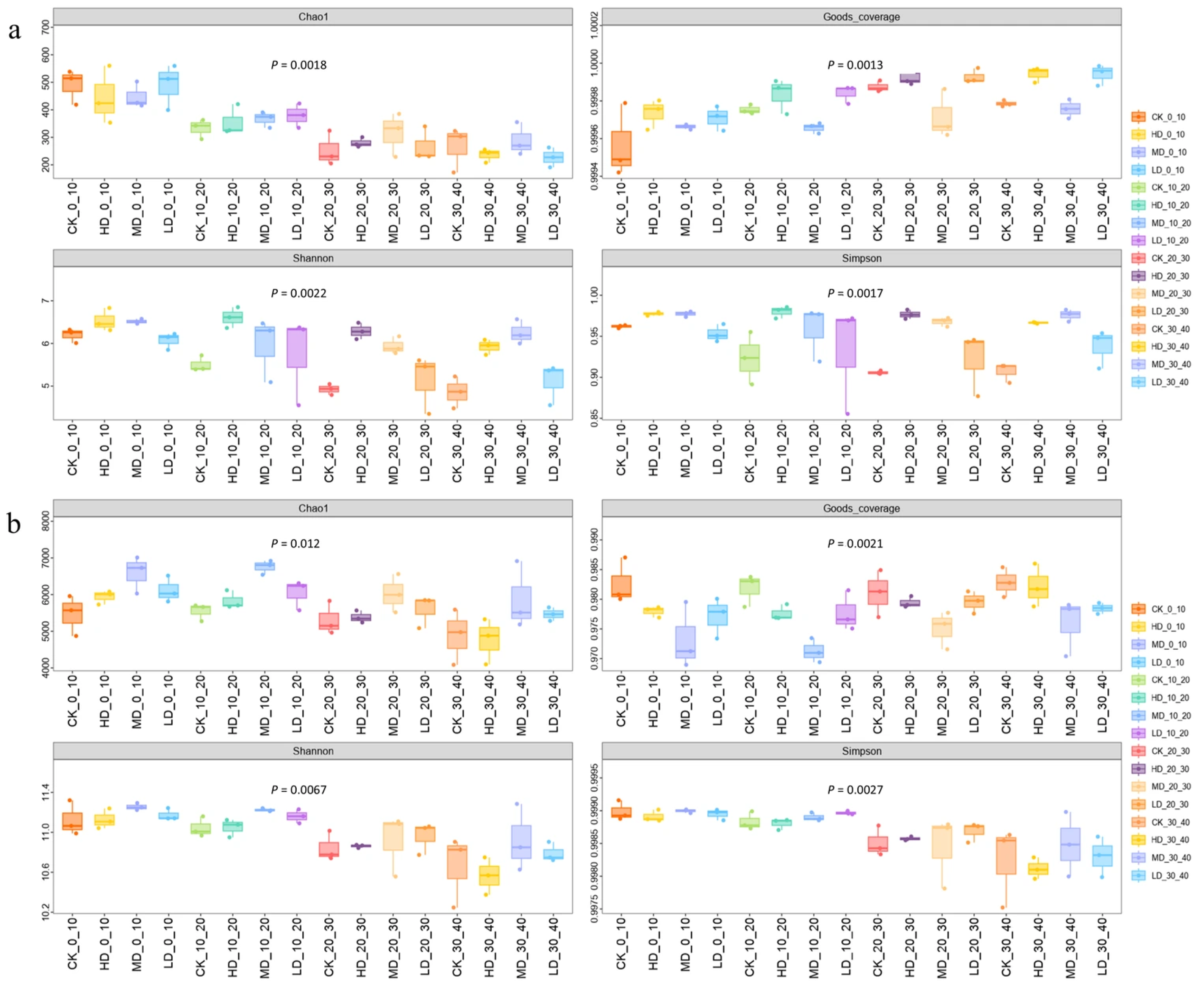

2.3.1. Alpha Diversity Analysis

2.3.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis

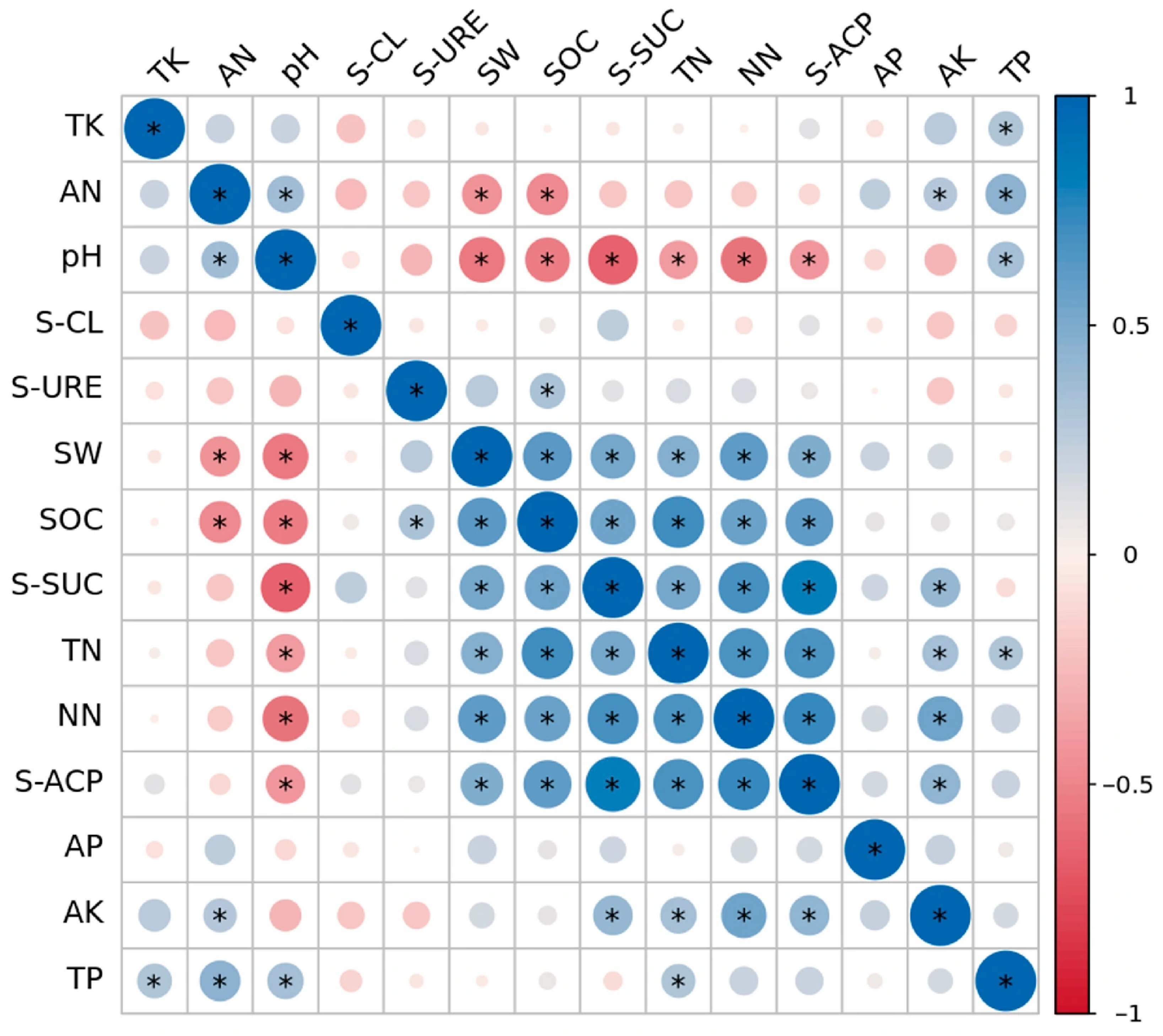

2.4. Correlations Among Soil Physicochemical Properties

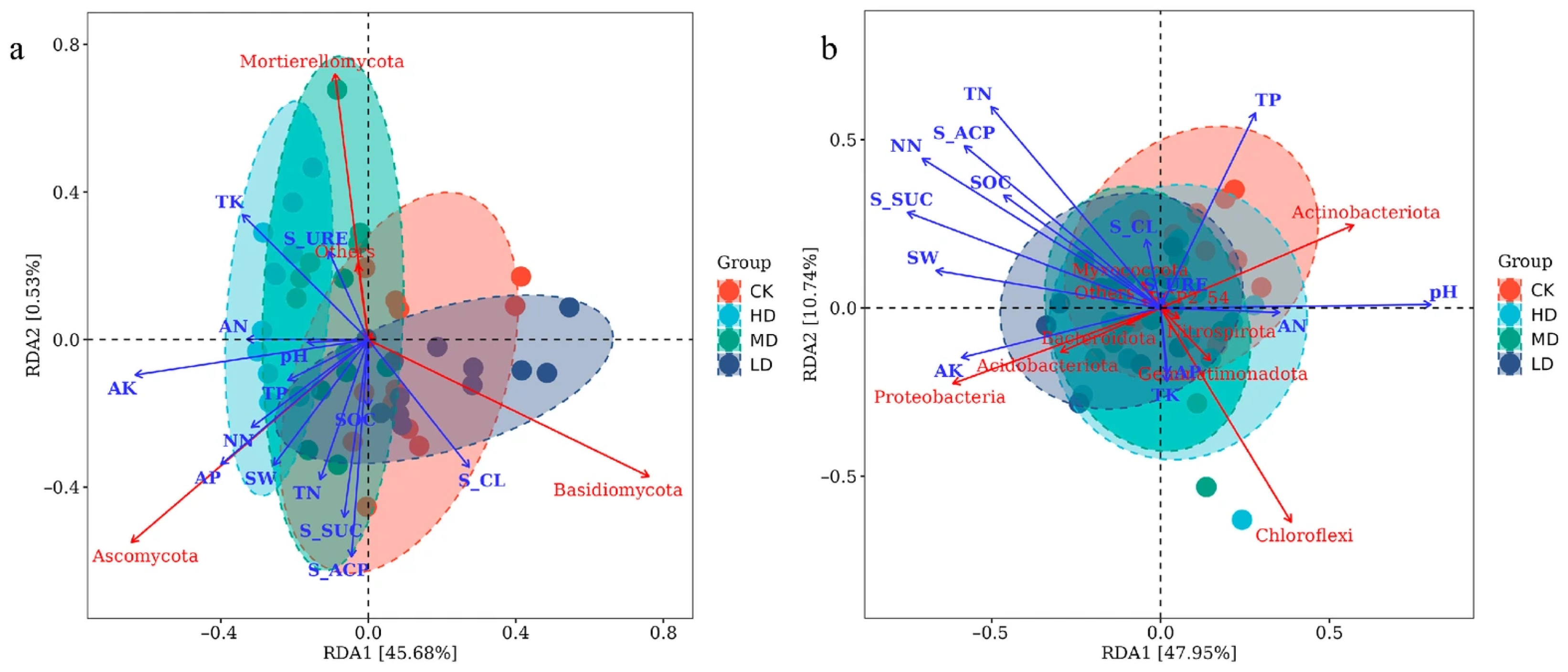

2.5. Main Environmental Factors Affecting Soil Microbial Community Structure

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Stand Density on Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.2. Effects of Stand Density on Soil Microbial Diversity and Community Composition

3.3. Relationship Between Soil Microbial Community Structure and Environmental Factors

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site Description

4.2. Experimental Design and Soil Sampling

4.3. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

4.4. DNA Extraction and Illumina Sequencing

4.5. Data Processing and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lull, C.; Bautista, I.; Lidón, A.; del Campo, A.D.; González-Sanchis, M.; García-Prats, A. Temporal effects of thinning on soil organic carbon pools, basal respiration and enzyme activities in a Mediterranean Holm oak forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 464, 118088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Hildebrand, F.; Forslund, S.K.; Anderson, J.L.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Bodegom, P.M.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Anslan, S.; Coelho, L.P.; Harend, H.; et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature 2018, 560, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, C.E. Litter decomposition: What controls it and how can we alter it to sequester more carbon in forest soils? Biogeochemistry 2010, 101, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L. Long-term impacts of stand density on soil fungal and bacterial communities for targeted cultivation of large-diameter Larix olgensis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 591, 122842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, S.; Li, S.Z.; Deng, Y. Advances in molecular ecology on microbial functional genes of carbon cycle. Microbiol. China 2017, 44, 1676–1689. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Meng, Z.X.; He, J.; Dong, Z.H.; Liu, K.Q.; Chen, W.Q. Soil microbial richness predicts ecosystem multifunctionality through co-occurrence network complexity in alpine meadow. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 2542–2558. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Deng, D.; Feng, Q.; Xu, Z.; Pan, H.; Li, H. Changes in litter input exert divergent effects on the soil microbial community and function in stands of different densities. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Fan, F.; Lin, Q.; Guo, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Rensing, C.; Cao, G.; et al. Effects of Different Stand Densities on the Composition and Diversity of Soil Microbiota in a Cunninghamia lanceolata Plantation. Plants 2025, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, L.; Ranger, J.; Binkley, D.; Rothe, A. Impact of several common tree species of European temperate forests on soil fertility. Ann. For. Sci. 2002, 59, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, L.E.; Vance, E.D.; Swanston, C.W.; Curtis, P.S. Harvest impacts on soil carbon storage in temperate forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilen, A.D.; Chen, C.R.; Parker, B.M.; Faggotter, S.J.; Burford, M.A. Differences in nitrate and phosphorus export between wooded and grassed riparian zones from farmland to receiving waterways under varying rainfall conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 598, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Hou, J.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, W. The changes in soil organic carbon stock and quality across a subalpine forest successional series. For. Ecosyst. 2024, 11, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Spatiotemporal patterns of soil nitrogen mineralization and nitrification in four temperate forests. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 3747–3758. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Burns, R.G.; DeForest, J.L.; Marxsen, J.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Stromberger, M.E.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Weintraub, M.N.; Zoppini, A. Soil enzymes in a changing environment: Current knowledge and future directions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 58, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Duan, Y.; Mulder, J.; Dörsch, P.; Zhu, W.; Xu-Ri; Huang, K.; Zheng, Z.; Kang, R.; Wang, C.; et al. Universal temperature sensitivity of denitrification nitrogen losses in forest soils. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Distribution of Extracellular Enzymes in Soils: Spatial Heterogeneity and Determining Factors at Various Scales. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Abarenkov, K.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1256688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Zhang, Y.T.; Zhang, J.H.; Chai, X.; Zhou, S.S.; Tong, Z.K. Effects of Chinese fir plantations with different densities on understory vegetation and soil microbial community structure. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 45, 62–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, J.; Tong, Z. Changes in Soil Nutrients and Acidobacteria Community Structure in Cunninghamia lanceolata Plantations. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2019, 55, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Dong, Y. Shift in soil bacterial communities from K- to r-strategists facilitates adaptation to grassland degradation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 2076–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 1978, 199, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Mikryukov, V.; Zizka, A.; Bahram, M.; Hagh-Doust, N.; Anslan, S.; Prylutskyi, O.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.T.; Maestre, T.; Pärn, J.; et al. Global Patterns in Endemicity and Vulnerability of Soil Fungi. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 6696–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louca, S.; Polz, M.F.; Mazel, F.; Albright, M.B.N.; Huber, J.A.; O’Connor, M.I.; Ackermann, M.; Aria, S.; Hahn, A.S.; Srivastava, D.S.; et al. Function and functional redundancy in microbial systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D.W.; Schink, S.J.; Patsalo, V.; Williamson, J.R.; Gerland, U.; Hwa, T. A global resource allocation strategy governs growth transition kinetics of Escherichia coli. Nature 2017, 551, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5111–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štursová, M.; Žifčáková, L.; Leigh, M.B.; Burgess, R.; Baldrian, P. Cellulose utilization in forest litter and soil: Identification of bacterial and fungal decomposers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 80, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Xu, J. Differential spatial responses and assembly mechanisms of soil microbial communities across region-scale Taiga ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 122653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, W.; Folman, L.B.; Summerbell, R.C.; Boddy, L. Living in a fungal world: Impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, L.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, K.; Hong, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, X.; Li, Z.; Li, F. Soil Microbial Communities and Their Relationship with Soil Nutrients in Different Density Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica Plantations in the Mu Us Sandy Land. Forests 2025, 16, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenzind, T.; Hättenschwiler, S.; Treseder, K.K.; Lehmann, A.; Rillig, M.C. Nutrient limitation of soil microbial processes in tropical forests. Ecol. Monogr. 2018, 88, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Jin, L.; Sang, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, B.T.; Jin, F.J. Characterization of potassium-solubilizing fungi, Mortierella spp., isolated from a poplar plantation rhizosphere soil. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bödeker, I.T.M.; Lindahl, B.D.; Olson, Å.; Clemmensen, K.E. Mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal guilds compete for the same organic substrates but affect decomposition differently. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, O.; Sardans, J.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Molowny-Horas, R.; Janssens, I.A.; Ciais, P.; Goll, D.; Richter, A.; Obersteiner, M.; Asensio, D.; et al. Global patterns of phosphatase activity in natural soils. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroz, S.; Oger, P.; Lepleux, C.; Collignon, C.; Frey-Klett, P.; Turpault, M.P. Bacterial weathering and its contribution to nutrient cycling in temperate forest ecosystems. Res. Microbiol. 2011, 162, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.E.; Grayston, S.J. Tree species influence on microbial communities in litter and soil: Current knowledge and research needs. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 309, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krah, F.-S.; Bässler, C.; Heibl, C.; Soghigian, J.; Schaefer, H.; Hibbett, D.S. Evolutionary dynamics of host specialization in wood-decay fungi. BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.T.; Robeson, M.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses. ISME J. 2009, 3, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Basu, A.; Ahmad, I.; Sayyed, R.Z.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Dailin, D.J.; Suriani, N.L. Recent understanding of soil Acidobacteria and their ecological significance: A critical review. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; Simpson, R.J. Soil microorganisms mediating phosphorus availability update on microbial phosphorus. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Guan, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, B.; Ma, M.; Qin, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S.; Cao, F.; Shen, D.; et al. Influence of 34-years of fertilization on bacterial communities in an intensively cultivated black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Tao, Y.; Huang, B.; Wen, D. Identifying the key taxonomic categories that characterize microbial community diversity using full-scale classification: A case study of microbial communities in the sediments of Hangzhou Bay. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, D.; DeGraaf, S.; Purdom, E.; Coleman-Derr, D. Drought and host selection influence bacterial community dynamics in the grass root microbiome. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2691–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegen, J.C.; Lin, X.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Chen, X.; Kennedy, D.W.; Murray, C.J.; Rockhold, M.L.; Konopka, A. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 2013, 7, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, M.M.; Helgason, B.L.; Lemke, R.L. Microbial crop residue decomposition dynamics in organic and conventionally managed soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.-Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.E.; Hawes, I.; Jungblut, A.D. 16S rRNA gene and 18S rRNA gene diversity in microbial mat communities in meltwater ponds on the McMurdo Ice Shelf, Antarctica. Polar Biol. 2021, 44, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Han, Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, T.; You, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Qiao, P.; Man, C.; et al. 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification and infectious disease diagnosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 739, 150974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stand Density | Longitude | Latitude | TH (m) | DBH (cm) | UBH (m) | CB (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 556 trees ha−1 | 112°04′29″ E | 41°05′11″ N | 15.6 ± 0.35 a | 22.1 ± 0.48 a | 4.2 ± 0.52 b | 4.5 ± 0.31 a |

| 1108 trees ha−1 | 112°03′48″ E | 41°05′36″ N | 15.2 ± 0.88 a | 19.9 ± 0.17 a | 4.4 ± 0.15 b | 4.69 ± 0.81 a |

| 2077 trees ha−1 | 112°04′05″ E | 41°05′23″ N | 14.8 ± 0.15 a | 16.04 ± 0.04 a | 4.9 ± 0.71 b | 3.26 ± 0.37 a |

| 2800 trees ha−1 | 112°03′29″ E | 41°05′33″ N | 14.5 ± 0.12 a | 15.75 ± 0.44 a | 5.3 ± 0.15 a | 2.73 ± 0.64 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Liu, L.; Hai, L.; Yang, H.; Zhao, K.; Di, Q.; Wang, Z. Stand Density Drives Soil Microbial Community Structure in Response to Nutrient Availability in Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilger Plantations. Plants 2025, 14, 3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243737

Li F, Liu L, Hai L, Yang H, Zhao K, Di Q, Wang Z. Stand Density Drives Soil Microbial Community Structure in Response to Nutrient Availability in Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilger Plantations. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243737

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fengzi, Lei Liu, Long Hai, Hongwei Yang, Kai Zhao, Qiuming Di, and Zhibo Wang. 2025. "Stand Density Drives Soil Microbial Community Structure in Response to Nutrient Availability in Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilger Plantations" Plants 14, no. 24: 3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243737

APA StyleLi, F., Liu, L., Hai, L., Yang, H., Zhao, K., Di, Q., & Wang, Z. (2025). Stand Density Drives Soil Microbial Community Structure in Response to Nutrient Availability in Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii (Mayr) Pilger Plantations. Plants, 14(24), 3737. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243737