Plant Functional Group Removal Shifts Soil Nematode Community and Decreases Soil Particulate Organic Carbon in an Alpine Meadow

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

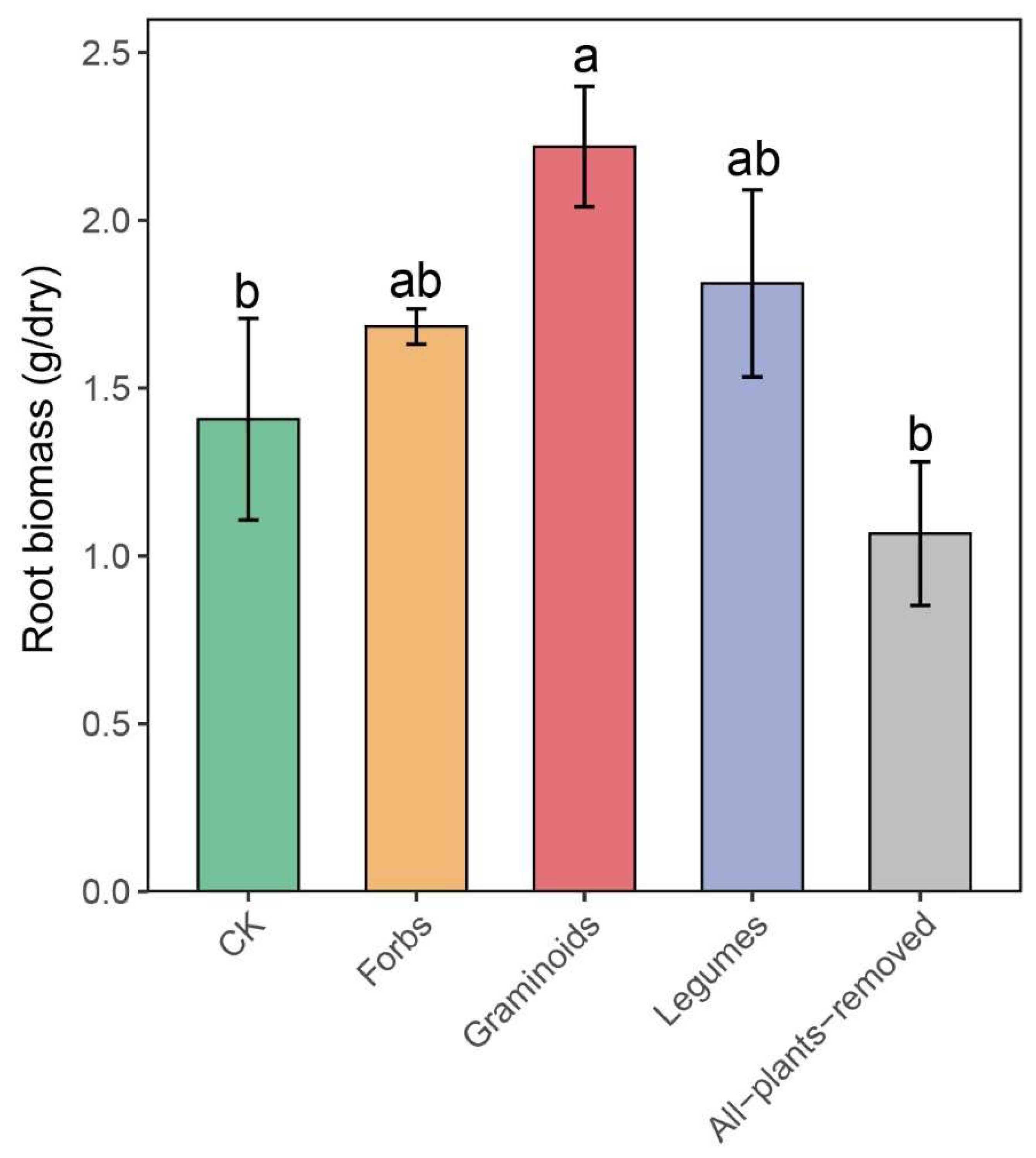

2.1. PFGs Removal Effects on Root Biomass and Root Properties

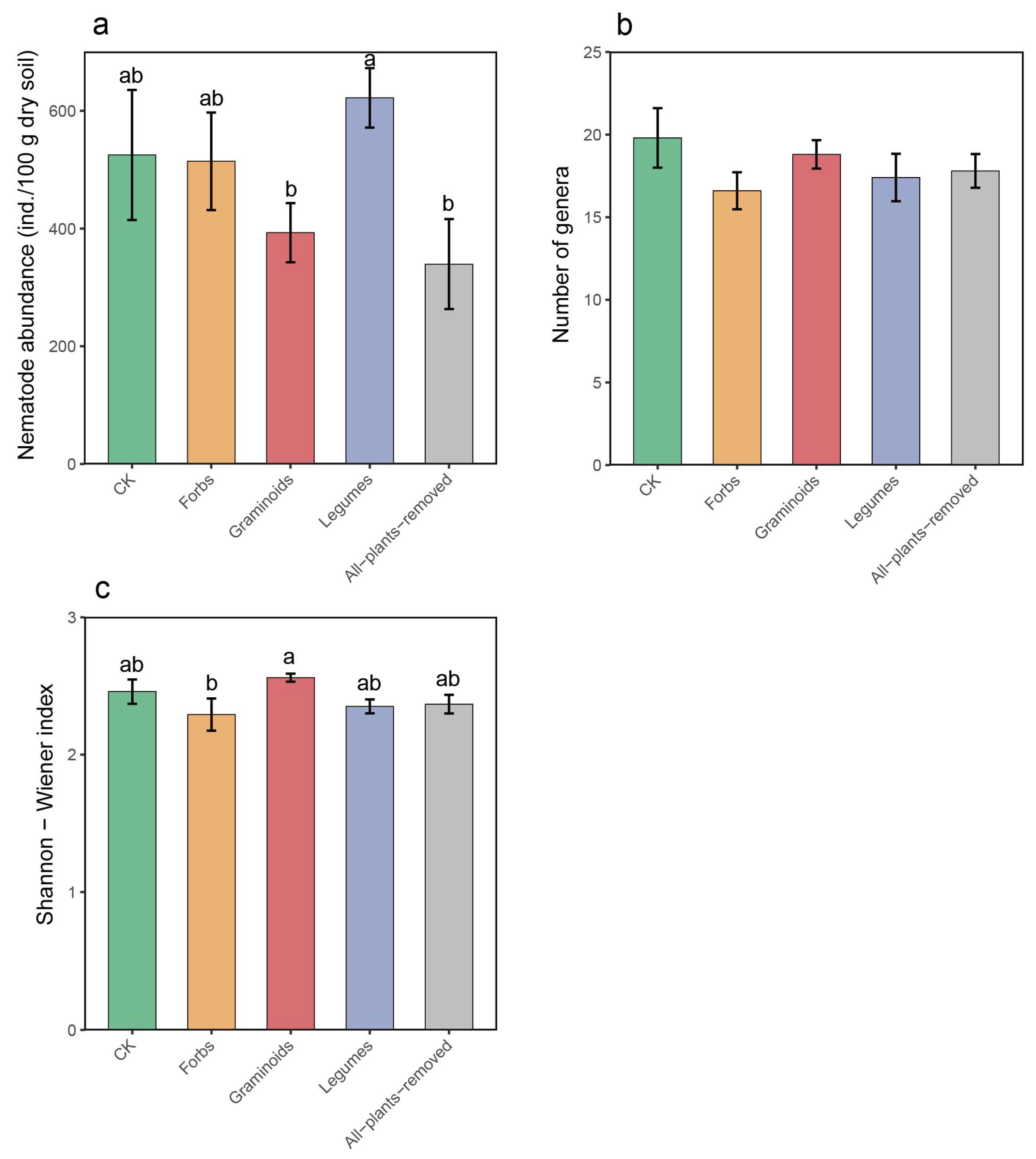

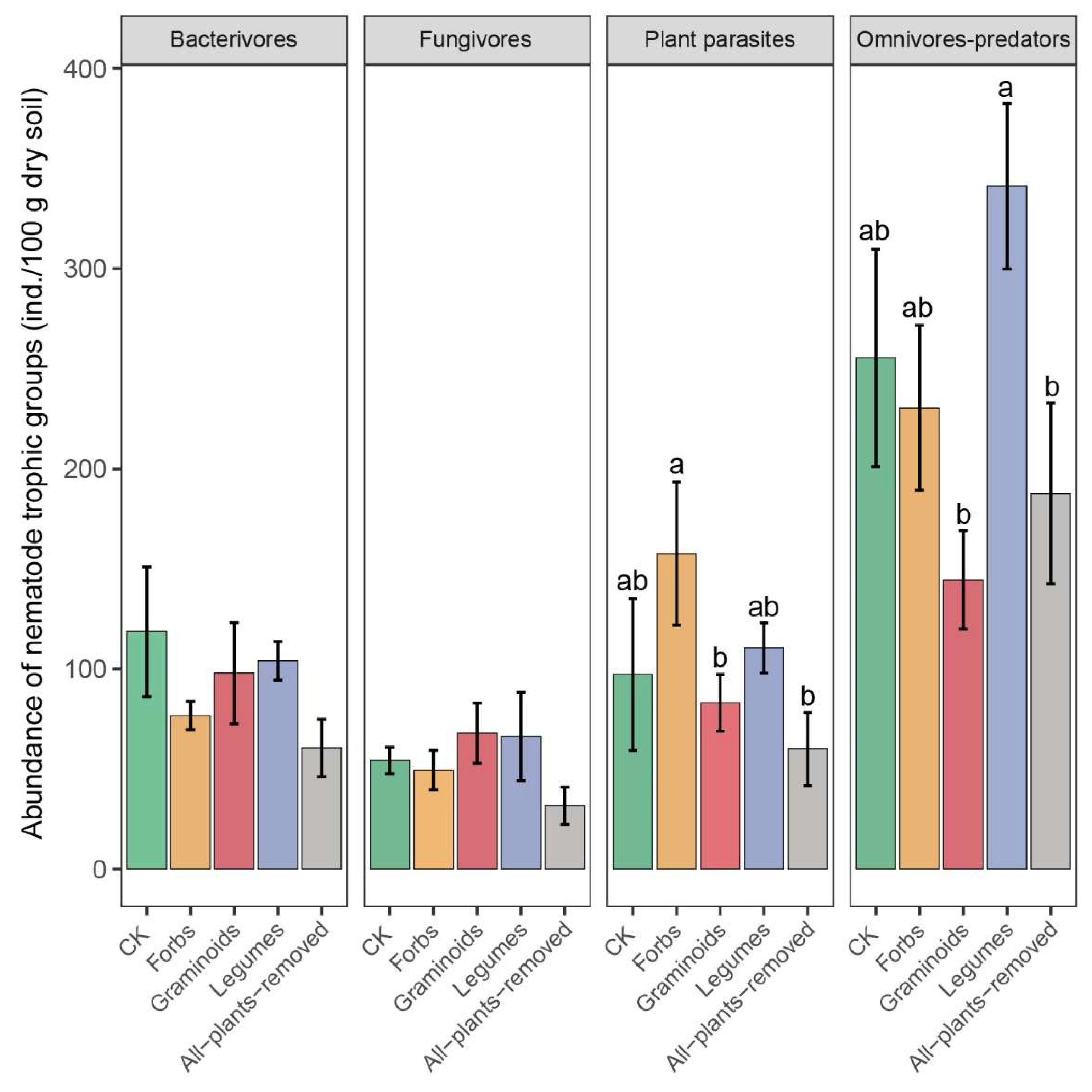

2.2. PFGs Removal Effects on Soil Nematode Community

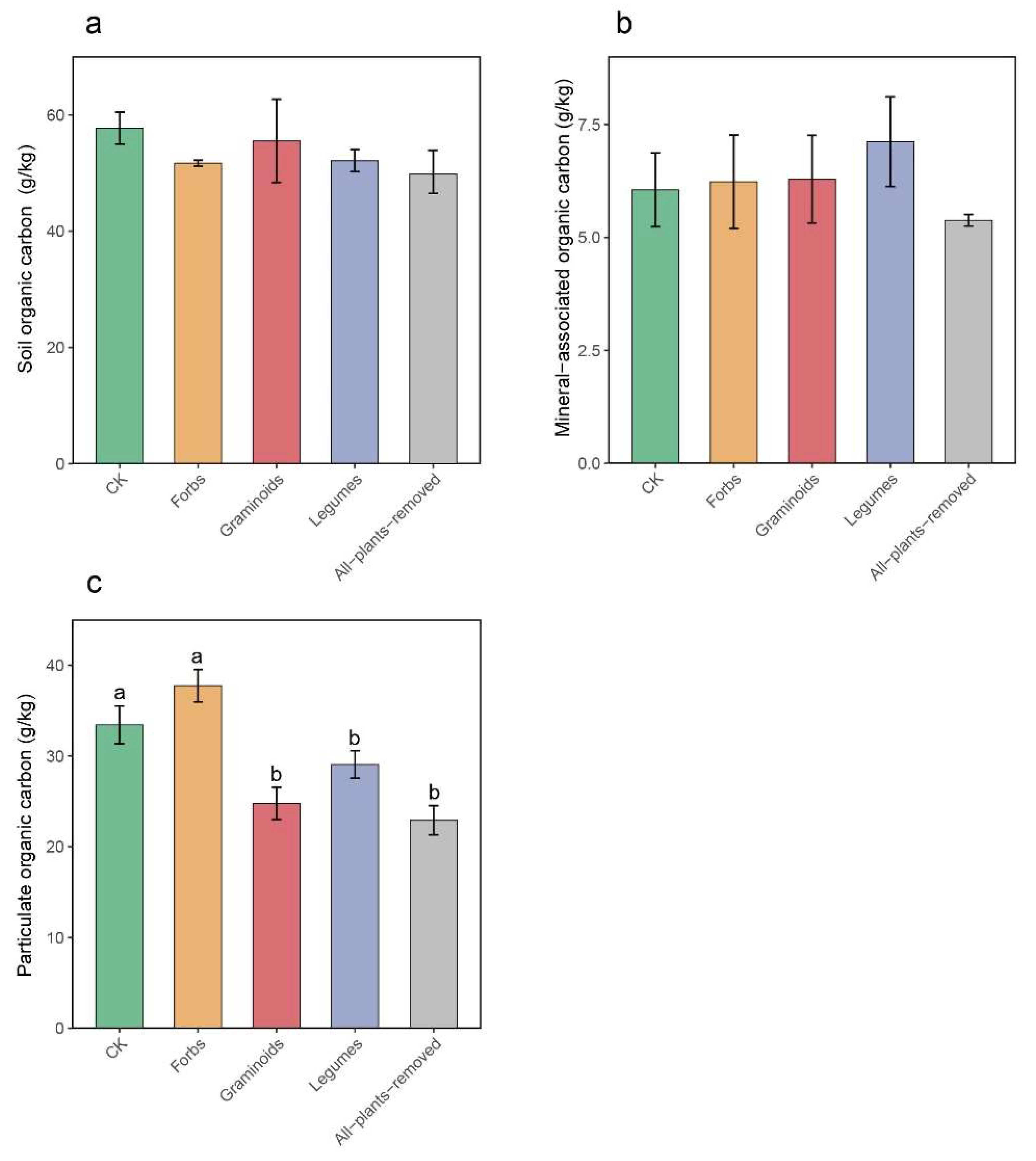

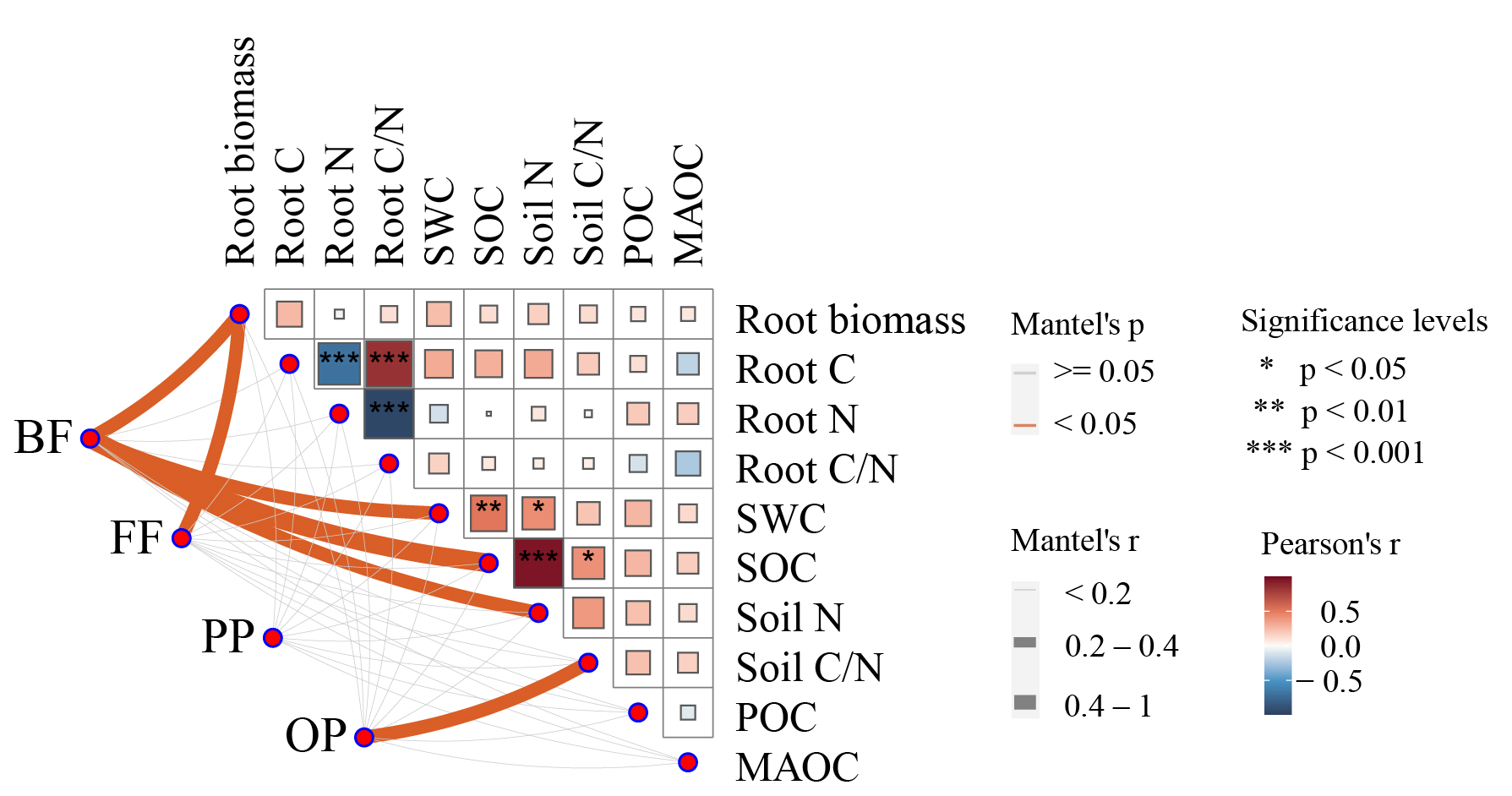

2.3. Linkage Between Soil Carbon Fractions and Nematode Community Under PFGs Removal

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of PFG Removal on Root Properties

3.2. Effects of PFG Removal on Soil Nematode Community

3.3. Linkage Between Nematode Community and Soil Carbon Fractions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Field Site Description

4.2. Soil Sampling

4.3. Nematode Extraction and Identification

- Shannon–Wiener index: H’ = −∑ Pi × ln(Pi);

- where Pi is the proportion of individuals in the i-th taxon.

- Nematode channel ratio: NCR = Ba/(Ba + Fu);

- Enrichment index: EI = 100 × (e/(e + b));

- Structure index: SI = 100 × (s/(s + b));

- Channel index: CI = 100 × 0.8Fu2/(0.8Fu2 + 3.2Ba1);

- Free-living nematode maturity index (Plant parasite index): MI (PPI) = ∑ υ(i) × f(i).

4.4. Soil Organic Matter

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hautier, Y.; Isbell, F.; Borer, E.T.; Seabloom, E.W.; Harpole, W.S.; Lind, E.M.; MacDougall, A.S.; Stevens, C.J.; Adler, P.B.; Alberti, J.J. Local loss and spatial homogenization of plant diversity reduce ecosystem multifunctionality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, F.; Tilman, D.; Polasky, S.; Loreau, M. The biodiversity-dependent ecosystem service debt. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, D.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Callaway, R.M.; Van der Putten, W.H. Terrestrial ecosystem responses to species gains and losses. Science 2011, 332, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grau-Andres, R.; Wardle, D.A.; Gundale, M.J.; Foster, C.N.; Kardol, P. Effects of plant functional group removal on CO2 fluxes and belowground C stocks across contrasting ecosystems. Ecology 2020, 101, e03170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.P.; Duan, J.C.; Xu, G.P.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, Z.H.; Rui, Y.C.; Luo, C.Y.; Xu, B.; Zhu, X.X.; Chang, X.F.; et al. Effects of warming and grazing on soil N availability, species composition, and ANPP in an alpine meadow. Ecology 2012, 93, 2365–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjurjav, H.; Gornish, E.S.; Hu, G.Z.; Wan, Y.F.; Li, Y.; Danjiu, L.B.; Gao, Q.Z. Temperature leads to annual changes of plant community composition in alpine grasslands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.L.; Du, G.Z.; Liu, Z.H.; Thirgood, S. Effect of fencing and grazing on a Kobresia-dominated meadow in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Plant Soil 2009, 319, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wen, S.J.; Hu, W.X.; Du, G.Z. Root-shoot competition interactions cause diversity loss after fertilization: A field experiment in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Plant Ecol. 2011, 4, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Zeynali, N.; Bazgir, M.; Omidipour, R.; Kohzadian, M.; Sagar, R.; Prevosto, B.J. Rapid recovery of the vegetation diversity and soil fertility after cropland abandonment in a semiarid oak ecosystem: An approach based on plant functional groups. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 155, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Tian, D.; Naeem, S.; Auerswald, K.; Elser, J.J.; Bai, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.J. Effects of functional diversity loss on ecosystem functions are influenced by compensation. Ecology 2016, 97, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Zhou, H.K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.W.; Li, Y.Z.; Qiao, L.L.; Yang, B.; Chen, K.L.; Liu, G.B.; et al. Loss of plant functional groups impacts soil carbon flow by changing multitrophic interactions within soil micro-food webs. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 178, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanin, N.; Kardol, P.; Farrell, M.; Kempel, A.; Ciobanu, M.; Nilsson, M.C.; Gundale, M.J.; Wardle, D.A. Effects of plant functional group removal on structure and function of soil communities across contrasting ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2019, 22, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.J.; Xu, D.H.; Knops, J.M.H.; Du, G.Z. Plant functional groups, grasses versus forbs, differ in their impact on soil carbon dynamics with nitrogen fertilization. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2016, 75, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.J.; Luo, S.; Wang, J.F.; Zheng, X.Y.; Zhou, X.; Xiang, Z.Q.; Liu, X.; Fang, X.W. Nitrogen deposition magnifies destabilizing effects of plant functional group loss. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viketoft, M.; Bengtsson, J.; Sohlenius, B.; Berg, M.P.; Petchey, O.; Palmborg, C.; Huss-Danell, K. Long-term effects of plant diversity and composition on soil nematode communities in model grasslands. Ecology 2009, 90, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viketoft, M.; Palmborg, C.; Sohlenius, B.; Huss-Danell, K.; Bengtsson, J. Plant species effects on soil nematode communities in experimental grasslands. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2005, 30, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Neher, D.A. Soil energy pathways of different ecosystems using nematode trophic group analysis: A meta analysis. Nematology 2014, 16, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zeng, Z.X.; He, X.Y.; Chen, H.S.; Wang, K. Effects of monoculture and mixed culture of grass and legume forage species on soil microbial community structure under different levels of nitrogen fertilization. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2015, 68, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, M.L.; Forrestel, E.J.; Chang, C.C.; La Pierre, K.J.; Burghardt, K.T.; Smith, M.D. Demystifying dominant species. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P. Benefits of plant diversity to ecosystems: Immediate, filter and founder effects. J. Ecol. 1998, 86, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Lauenroth, W.K. Dominant species, rather than diversity, regulates temporal stability of plant communities. Oecologia 2011, 166, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, T.; Bongers, M.J. Functional diversity of nematodes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1998, 10, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, T.; Ferris, H. Nematode community structure as a bioindicator in environmental monitoring. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, H.; Bongers, T.; de Goede, R.G.M. A framework for soil food web diagnostics: Extension of the nematode faunal analysis concept. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2001, 18, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A. The ecological role of biodiversity in agroecosystems. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 1999, 74, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortois, R.; Veen, G.F.; Duyts, H.; Abbas, M.; Strecker, T.; Kostenko, O.; Eisenhauer, N.; Scheu, S.; Gleixner, G.; De Deyn, G.B.; et al. Possible mechanisms underlying abundance and diversity responses of nematode communities to plant diversity. Ecosphere 2017, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikoyi, I.; Grange, G.; Finn, J.A.; Brennan, F.P. Plant diversity enhanced nematode-based soil quality indices and changed soil nematode community structure in intensively-managed agricultural grasslands. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2023, 118, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viketoft, M.; Sohlenius, B.; Boström, S.; Palmborg, C.; Bengtsson, J.; Berg, M.P.; Huss-Danell, K. Temporal dynamics of soil nematode communities in a grassland plant diversity experiment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.J.; Yan, R.R.; Zhao, J.L.; Li, L.H.; Hu, Y.F.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, J.; McLaughlin, N.B.; Zhao, D.; Xin, X.P. Effects of grazing intensity on soil nematode community structure and function in different soil layers in a meadow steppe. Plant Soil 2022, 471, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.M.; Brigham, L.M.; de Mesquita, C.P.B.; Gattoni, K.M.; Gendron, E.M.; Hahn, P.G.; Schmidt, S.K.; Smith, J.G.; Suding, K.N.; Porazinska, D.L. Trophic group specific responses of alpine nematode communities to 18 years of N addition and codominant plant removal. Plant Soil 2023, 494, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Niu, S.; Luo, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Y.J. Drivers of microbially and plant-derived carbon in topsoil and subsoil. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 6188–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, A.; Liang, Y.; Cornell, C.R.; Guo, X.; Bai, E.; Hou, H.; Wang, D.J. Differential contribution of microbial and plant-derived organic matter to soil organic carbon sequestration over two decades of natural revegetation and cropping. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Fan, J.; Zhang, L.; Lv, Q.; Wang, T.; Meng, Y.; Hu, H.; Gao, H.; Wang, J.; Ren, X.J. The accumulation of plant-and microbial-derived carbon and its contribution to soil organic carbon in reclaimed saline-sodic farmland. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 202, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Eisenhauer, N.; Sierra, C.A.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Griffiths, R.I.; Mellado-Vazquez, P.G.; Malik, A.A.; Roy, J.; Scheu, S.; et al. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, D.; Tilman, D.J. Plant functional composition influences rates of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.J.; Han, X.Z.; Li, N.; Yan, J.; Xu, Y.L. Effect of organic amendment amount on soil nematode community structure and metabolic footprints in soybean phase of a soybean-maize rotation on Mollisols. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, P.; Entemake, W.; Guo, Z.Q.; Xue, S. Concentration-dependent impacts of microplastics on soil nematode community in bulk soils of maize: Evidence from a pot experiment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, F.H.; Luo, Y.Q. A soil nematode community response to reclamation of salinized abandoned farmland. Zool. Stud. 2021, 60, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Fu, S. Legume-soil interactions: Legume addition enhances the complexity of the soil food web. Plant Soil 2014, 385, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, M.; Jing, S. Effects of different carbon inputs on soil nematode abundance and community composition. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2021, 163, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.C.; Guerra, C.A.; Cano-Díaz, C.; Zeiss, R.; Carvalho-Santos, C.; Carvalho, R.P.; Costa, S.R. Effects of protected areas on soil nematode communities in forests of the North of Portugal. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 33, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallee, J.M.; Soong, J.L.; Cotrufo, M.F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.T.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Mou, Z.J.; Zhu, X.M.; Wu, W.J.; Zhang, J.; Kuang, L.H.; Wang, J.; Hui, D.F.; et al. Divergent accumulation of amino sugars and lignins mediated by soil functional carbon pools under tropical forest conversion. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.T.; Chen, X.; Yao, S.H.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, B. Responses of soil mineral-associated and particulate organic carbon to carbon input: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessler, H.; Temperton, V.M.; Roscher, C.; Buchmann, N.; Schmid, B.; Schulze, E.D.; Weisser, W.W.; Engels, C. Aboveground overyielding in grassland mixtures is associated with reduced biomass partitioning to belowground organs. Ecology 2009, 90, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, J.R.; Novoplansky, A.; Turkington, R. Few effects of plant functional group identity on ecosystem properties in an annual desert community. Plant Ecol. 2016, 217, 1379–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenek, J.M.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Gessler, A.; Gockele, A.; De Luca, E.; Temperton, V.M.; Ebeling, A.; Roscher, C.; et al. Long-term study of root biomass in a biodiversity experiment reveals shifts in diversity effects over time. Oikos 2014, 123, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.S.; Jing, G.H.; Jin, J.W.; Wei, L.; Liu, J.; Cheng, J.M. Identifying drivers of root community compositional changes in semiarid grassland on the Loess plateau after long-term grazing exclusion. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 99, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haling, R.E.; Yang, Z.J.; Shadwell, N.; Culvenor, R.A.; Stefanski, A.; Ryan, M.H.; Sandral, G.A.; Kidd, D.R.; Lambers, H.; Simpson, R.J. Growth and root dry matter allocation by pasture legumes and a grass with contrasting external critical phosphorus requirements. Plant Soil 2016, 407, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha, C.; Doerner, P. The impact of the rhizobia-legume symbiosis on host root system architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3902–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnari, F.; Maggio, A.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M.J.C.; Agriculture, B.T.i. Multiple benefits of legumes for agriculture sustainability: An overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, A.; Meyer, A.H.; Schmid, B. Plant diversity affects culturable soil bacteria in experimental grassland communities. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.L.; Tian, P.; Wang, Q.K.; Li, W.B.; Sun, Z.L.; Yang, H. Effects of root dominate over aboveground litter on soil microbial biomass in global forest ecosystems. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pang, X.; Li, N.; Qi, K.; Huang, J.; Yin, C.J.C. Effects of vegetation type, fine and coarse roots on soil microbial communities and enzyme activities in eastern Tibetan plateau. Catena 2020, 194, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Zhou, Y.; Su, J.; Yang, F.J.F.i.P.S. Effects of plant functional group loss on soil microbial community and litter decomposition in a steppe vegetation. Front. Plant. Sci. 2017, 8, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Gong, L.; Luo, Y.; Tang, J.; Ding, Z.; Li, X.J.F.i.P.S. Effects of litter and root manipulations on soil bacterial and fungal community structure and function in a schrenk’s spruce (Picea schrenkiana) forest. Front. Plant. Sci. 2022, 13, 849483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobe, P.D.D.; Erley, G.S.A.; Hoppner, F.; Schrader, S. Nematode abundances and community diversity under energy crop (maize and sainfoin) cultivation in annual and perennial cropping systems. Biomass Bioenerg. 2023, 175, 106844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Qi, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.J.B.e. Soil nematode community and crop productivity in response to 5-year biochar and manure addition to yellow cinnamon soil. BMC Ecol. 2020, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Niu, K. Effect of soil environment on functional diversity of soil nematodes in Tibetan alpine meadows. Biodiversity Science 2020, 28, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsi, M.; Saeki, T.J.A.o.b. On the factor light in plant communities and its importance for matter production. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.L.; Maltais-Landry, G.; Liao, H.L. How soil biota regulate C cycling and soil C pools in diversified crop rotations. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.H.; Shi, Y.; Mi, W.B.; Yue, S.L.; She, J.; Zhang, F.H.; Guo, R.; He, H.Y.; Wu, T.; Li, H.X.; et al. Effects of desert plant communities on soil enzyme activities and soil organic carbon in the proluvial fan in the eastern foothills of the Helan Mountain in Ningxia, China. J. Arid Land 2024, 16, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canarini, A.; Mariotte, P.; Ingram, L.; Merchant, A.; Dijkstra, F.A. Mineral-Associated Soil Carbon is Resistant to Drought but Sensitive to Legumes and Microbial Biomass in an Australian Grassland. Ecosystems 2018, 21, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Boot, C.M.; Denef, K.; Paul, E. The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, P.; Cesarz, S.; Liu, T.; Roscher, C.; Eisenhauer, N. Effects of plant species diversity on nematode community composition and diversity in a long-term biodiversity experiment. Oecologia 2021, 197, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neher, D.A. Ecology of Plant and Free-Living Nematodes in Natural and Agricultural Soil. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2010, 48, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.J.; Sun, B.; Jin, C.; Wang, F. Soil aggregate stratification of nematodes and microbial communities affects the metabolic quotient in an acid soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.Q.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Li, D.B.; Luo, X.Z.; Wu, J.P. Global patterns and controls of soil nematode responses to nitrogen enrichment: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 163, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, H. Contribution of nematodes to the structure and function of the soil food web. J. Nematol. 2010, 42, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F.X.; Ou, W.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wen, D.Z. Vertical distribution and seasonal fluctuation of nematode trophic groups as affected by land use. Pedosphere 2006, 16, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshita, A.; Khan, W.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Ullah, A.; Khan, A.; Jalal, A.; Iqbal, B. Dynamic changes of soil nematodes between bulk and rhizosphere soils in the maize (Zea mays L.)/alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) intercropping system. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treonis, A.M.; Unangst, S.K.; Kepler, R.M.; Buyer, J.S.; Cavigelli, M.A.; Mirsky, S.B.; Maul, J.E. Characterization of soil nematode communities in three cropping systems through morphological and DNA metabarcoding approaches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Guo, J.; Xu, X.Y.; Yan, X.B.; Zhang, K.C.; Qiu, Y.P.; Zhao, Q.Z.; Huang, K.L.; Luo, X.; Yang, F.; et al. Soil acidification alters root morphology, increases root biomass but reduces root decomposition in an alpine grassland. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, L.G.; Jiang, X.; Guo, R.; Wan, W.J.; Ye, L.P.; Drost, T.A.; Zhou, X.H.; Guo, H.; Zuo, J.; et al. Impact of remaining roots on soil nematode communities in an aboveground plant functional group removal experiment. Plant Soil 2024, 498, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Q.; Chen, X.Y.; Qin, J.T.; Wang, D.; Griffiths, B.; Hu, F. A sequential extraction procedure reveals that water management affects soil nematode communities in paddy fields. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 40, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, G.W.; Bongers, T.; Degoede, R.G.M.; Freckman, D.W.; Georgieva, S.S. Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera—An outline for soil ecologists. J. Nematol. 1993, 25, 315–331. [Google Scholar]

- Cambardella, C.A.; Elliott, E.T. Particulate soil organic-matter changes across a grassland cultivation sequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, R package version 2.6-2; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Index | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Root properties | ||

| Root biomass | 4.716 | 0.006 |

| Root carbon | 0.253 | 0.905 |

| Root nitrogen | 0.704 | 0.598 |

| Root carbon to nitrogen ratio | 0.730 | 0.580 |

| Soil properties | ||

| Soil water content | 0.999 | 0.427 |

| Soil organic carbon | 0.527 | 0.717 |

| Soil nitrogen | 0.615 | 0.657 |

| Soil carbon to nitrogen ratio | 1.181 | 0.348 |

| MAOC | 0.122 | 0.973 |

| POC | 14.972 | 0.000 |

| Index | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| Nematode abundance | ||

| Total abundance | 4.395 | 0.011 |

| Bacterivores abundance | 2.337 | 0.090 |

| Fungivores abundance | 1.750 | 0.179 |

| Plant parasites | 4.719 | 0.008 |

| Omnivores-predators | 4.747 | 0.008 |

| Nematode indices | ||

| Shannon–Wiener index | 3.321 | 0.031 |

| Nematode channel ratio | 0.487 | 0.745 |

| Channel index | 2.569 | 0.069 |

| Enrichment index | 0.360 | 0.834 |

| Structure index | 5.933 | 0.002 |

| Free-living nematode maturity index | 27.475 | 0.000 |

| Plant parasite index | 7.392 | 0.000 |

| Genera | Trophic Group | Treatments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | Forbs | Graminoids | Legumes | Removal All | ||

| Acrobeloides | Ba2 | 5.51 ± 1.14 | 5.40 ± 0.49 | 7.37 ± 1.59 | 4.87 ± 1.70 | 7.00 ± 1.97 |

| Cephalobus | Ba2 | 3.77 ± 1.60 | 2.81 ± 0.51 | 4.75 ± 2.12 | 2.02 ± 1.07 | 1.27 ± 0.68 |

| Plectus | Ba2 | 4.87 ± 1.12 | 1.90 ± 0.68 | 3.94 ± 0.87 | 1.82 ± 0.77 | 1.82 ± 0.95 |

| Alaimus | Ba4 | 3.86 ± 1.08 | 2.83 ± 0.86 | 1.02 ± 0.39 | 3.25 ± 1.17 | 2.06 ± 0.78 |

| Eucephalobus | Ba2 | 0.78 ± 0.37 | 0.74 ± 0.53 | 1.81 ± 0.64 | 1.90 ± 0.54 | 2.50 ± 0.96 |

| Mesorhabditis | Ba1 | 0 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 2.54 ± 1.43 | 0.58 ± 0.38 | 0.36 ± 0.22 |

| Anaplectus | Ba2 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.60 ± 0.38 | 0.88 ± 0.47 | 0.99 ± 0.79 |

| Panagrolaimus | Ba1 | 0.95 ± 0.52 | 0.36 ± 0.36 | 0 | 0.69 ± 0.50 | 0.79 ± 0.48 |

| Wilsonema | Ba2 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.58 ± 0.39 | 0.55 ± 0.36 | 0.37 ± 0.23 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Protorhabditis | Ba1 | 0.39 ± 0.24 | 0.79 ± 0.79 | 0.36 ± 0.22 | 0 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Teratocephalus | Ba3 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.18 ± 0.18 | 0.37 ± 0.22 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Diplogaster | Ba1 | 0.76 ± 0.36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Amphidelus | Ba4 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0 | 0 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0 |

| Bastiania | Ba3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Rhabditis | Ba1 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 ± 0.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Filenchus | Fu2 | 7.63 ± 3.15 | 5.41 ± 0.88 | 11.25 ± 2.42 | 3.75 ± 1.82 | 3.78 ± 1.03 |

| Tylencholaimus | Fu4 | 3.99 ± 1.37 | 3.91 ± 1.13 | 5.10 ± 0.85 | 7.31 ± 3.67 | 5.49 ± 1.64 |

| Leptonchus | Fu4 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Helicotylenchus | PP3 | 13.39 ± 4.42 | 27.46 ± 3.24 | 19.26 ± 2.46 | 11.39 ± 2.51 | 12.11 ± 3.38 |

| Pratylenchus | PP3 | 2.48 ± 0.77 | 2.25 ± 0.75 | 1.27 ± 0.54 | 5.81 ± 3.69 | 4.33 ± 1.44 |

| Tylenchus | PP2 | 0.38 ± 0.24 | 0 | 0.78 ± 0.53 | 0.76 ± 0.37 | 0.75 ± 0.55 |

| Tylenchorhynchus | PP4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.41 ± 0.41 |

| Aporcelaimus | OP5 | 18.96 ± 1.82 | 16.99 ± 3.26 | 11.38 ± 3.19 | 16.36 ± 3.44 | 19.24 ± 1.92 |

| Eudorylaimus | OP4 | 12.74 ± 1.65 | 9.39 ± 2.33 | 11.36 ± 4.10 | 12.34 ± 2.89 | 17.17 ± 4.35 |

| Discolaimus | OP4 | 3.85 ± 1.12 | 7.82 ± 2.21 | 3.97 ± 1.26 | 6.53 ± 2.21 | 7.42 ± 3.74 |

| Epidorylaimus | OP4 | 1.93 ± 1.03 | 4.12 ± 0.65 | 1.70 ± 0.66 | 7.18 ± 4.63 | 3.91 ± 1.14 |

| Prodorylaimus | OP4 | 5.47 ± 2.58 | 1.31 ± 0.55 | 1.08 ± 0.72 | 6.06 ± 4.48 | 2.21 ± 1.18 |

| Dorylaimellus | OP5 | 3.48 ± 2.78 | 2.59 ± 1.41 | 3.45 ± 0.33 | 2.31 ± 1.00 | 3.24 ± 1.72 |

| Mononchus | OP4 | 0.57 ± 0.23 | 0.37 ± 0.23 | 2.01 ± 0.93 | 0.89 ± 0.47 | 0.37 ± 0.22 |

| Mesodorylaimus | OP4 | 1.16 ± 0.57 | 0.36 ± 0.22 | 1.10 ± 0.67 | 0.58 ± 0.40 | 0.73 ± 0.53 |

| Microdorylaimus | OP4 | 0.96 ± 0.43 | 1.09 ± 0.67 | 0.74 ± 0.54 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Prionchulus | OP4 | 0.57 ± 0.23 | 0.18 ± 0.18 | 1.64 ± 0.83 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.38 ± 0.38 |

| Tripyla | OP3 | 0.36 ± 0.36 | 0.18 ± 0.18 | 0.42 ± 0.26 | 0.18 ± 0.18 | 0.41 ± 0.41 |

| Mylonchulus | OP4 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0 | 0.88 ± 0.47 | 0.18 ± 0.18 |

| Axonchium | OP5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.51 ± 0.51 | 0 |

| Enchodelus | OP4 | 0 | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, L.; Ye, L.; Zhou, X.; Guo, H.; Zuo, J.; Wang, P.; Zheng, Y. Plant Functional Group Removal Shifts Soil Nematode Community and Decreases Soil Particulate Organic Carbon in an Alpine Meadow. Plants 2025, 14, 3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243728

Huang L, Ye L, Zhou X, Guo H, Zuo J, Wang P, Zheng Y. Plant Functional Group Removal Shifts Soil Nematode Community and Decreases Soil Particulate Organic Carbon in an Alpine Meadow. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243728

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Ligai, Luping Ye, Xianhui Zhou, Hui Guo, Juan Zuo, Peng Wang, and Yong Zheng. 2025. "Plant Functional Group Removal Shifts Soil Nematode Community and Decreases Soil Particulate Organic Carbon in an Alpine Meadow" Plants 14, no. 24: 3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243728

APA StyleHuang, L., Ye, L., Zhou, X., Guo, H., Zuo, J., Wang, P., & Zheng, Y. (2025). Plant Functional Group Removal Shifts Soil Nematode Community and Decreases Soil Particulate Organic Carbon in an Alpine Meadow. Plants, 14(24), 3728. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243728