Combining Hyperspectral Imaging with Ensemble Learning for Estimating Rapeseed Chlorophyll Content Under Different Waterlogging Durations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

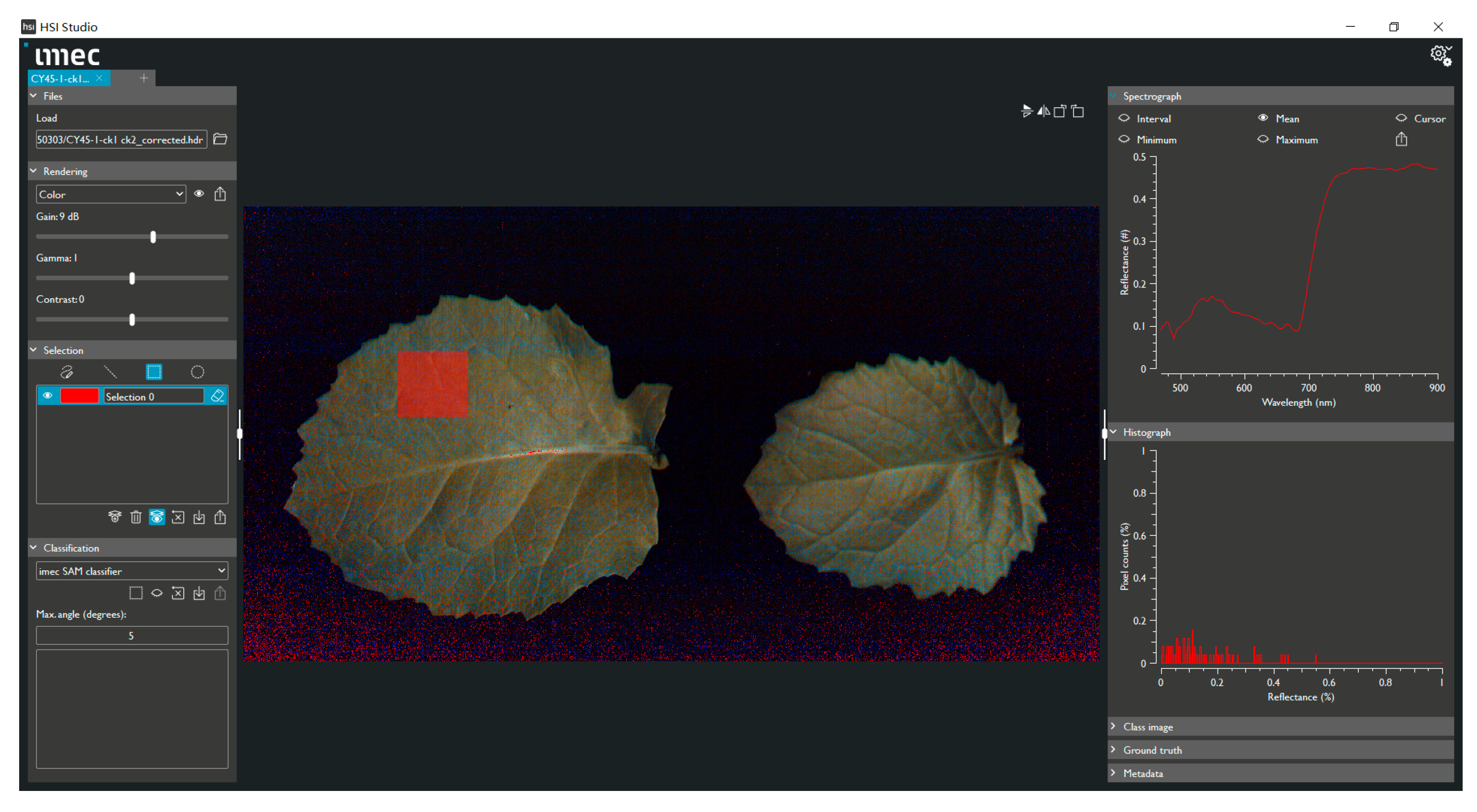

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.3. Spectral and Vegetation Index Construction and Screening

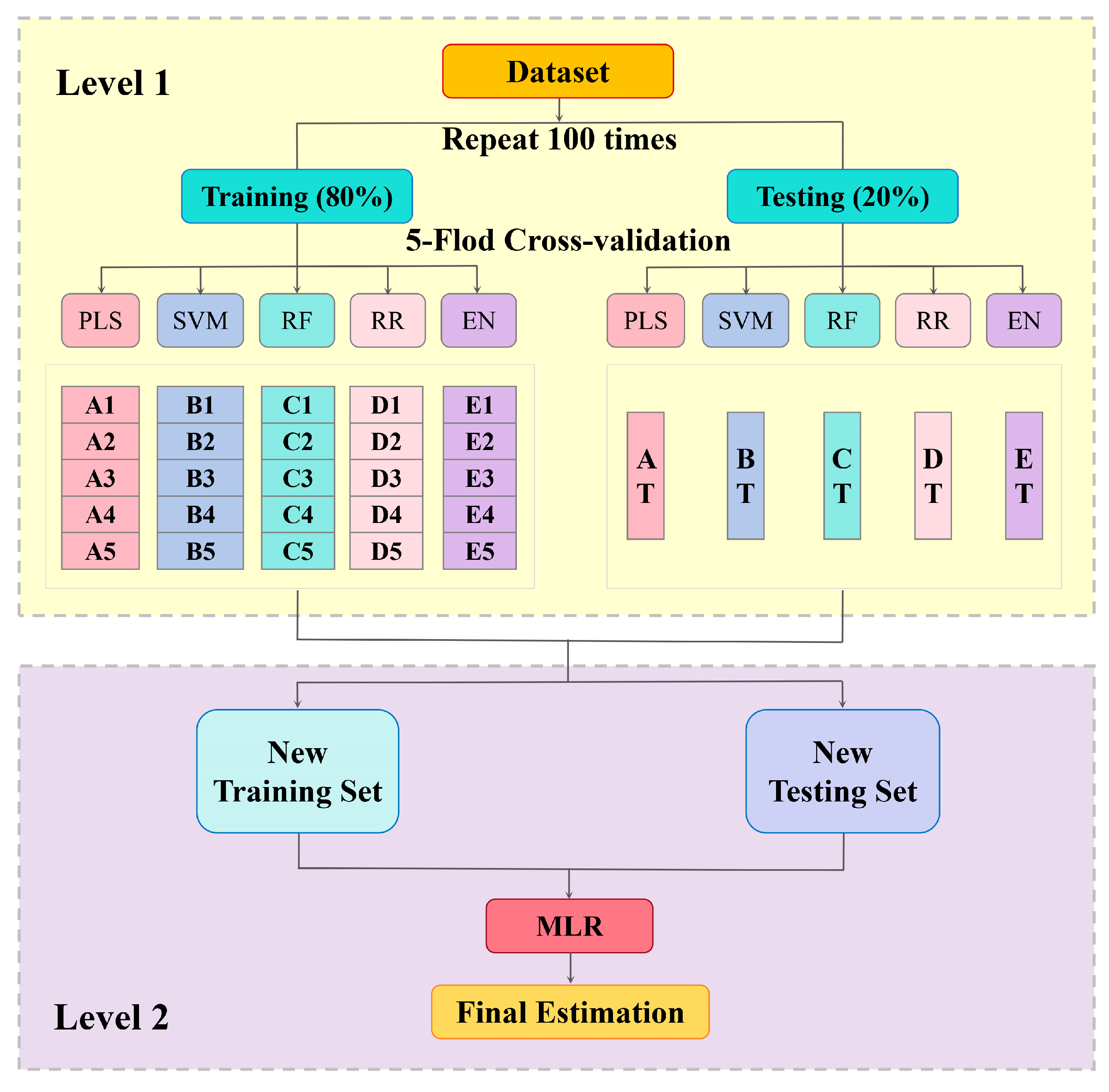

2.4. Modeling for SPAD Value Estimation

2.5. Model Training and Evaluation

3. Results

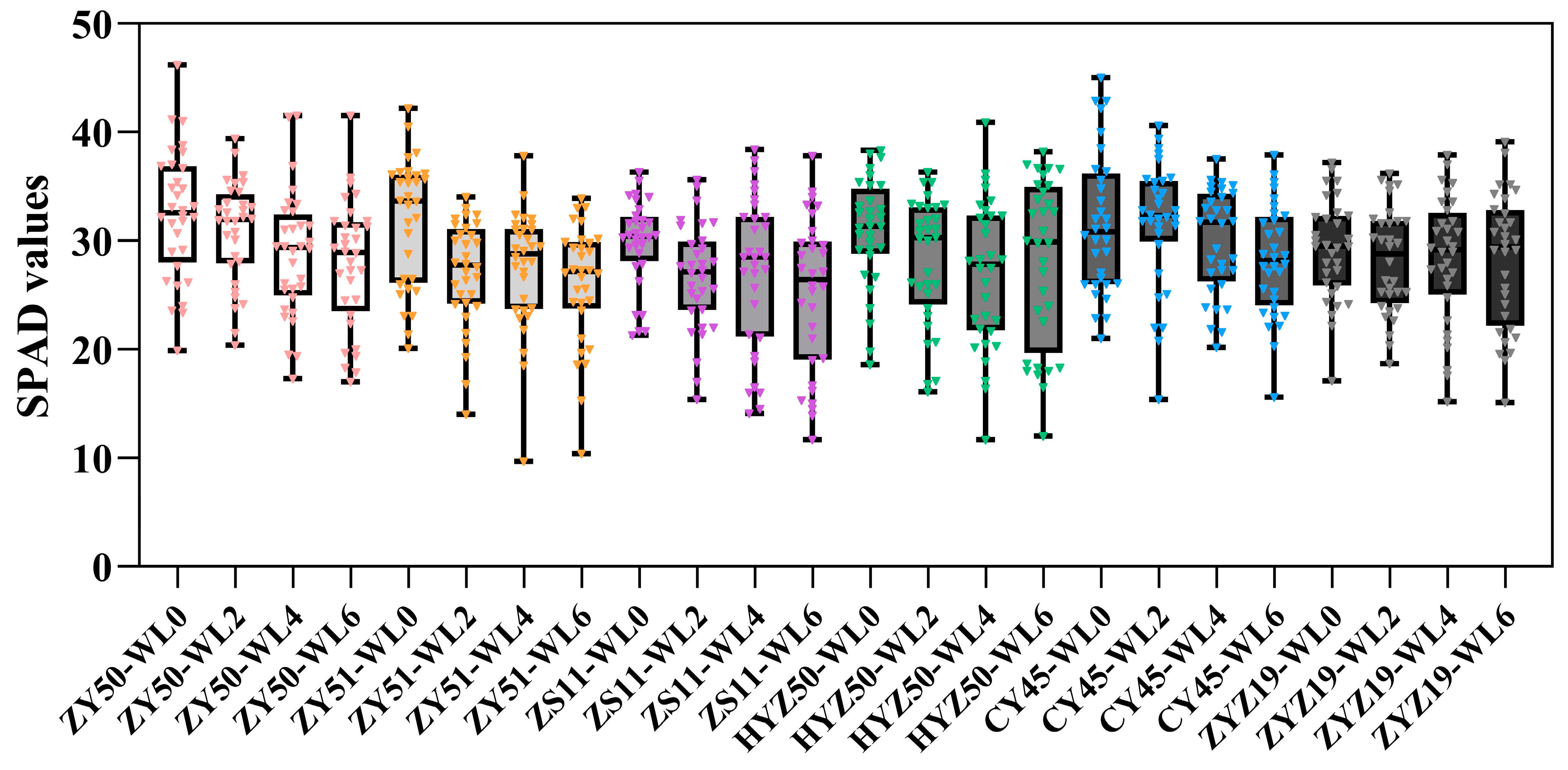

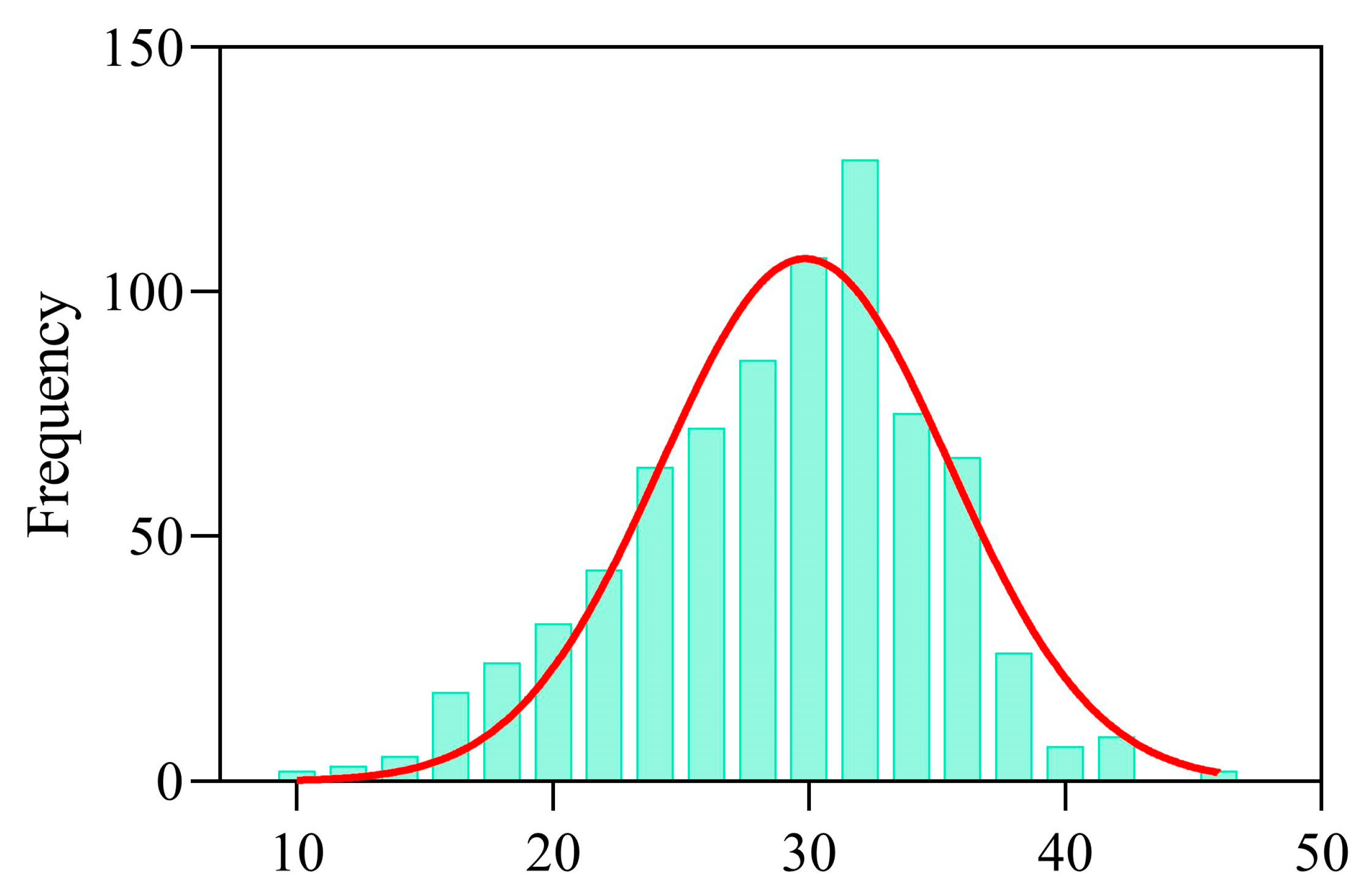

3.1. Statistical Analysis of SPAD Values Under Different Treatments

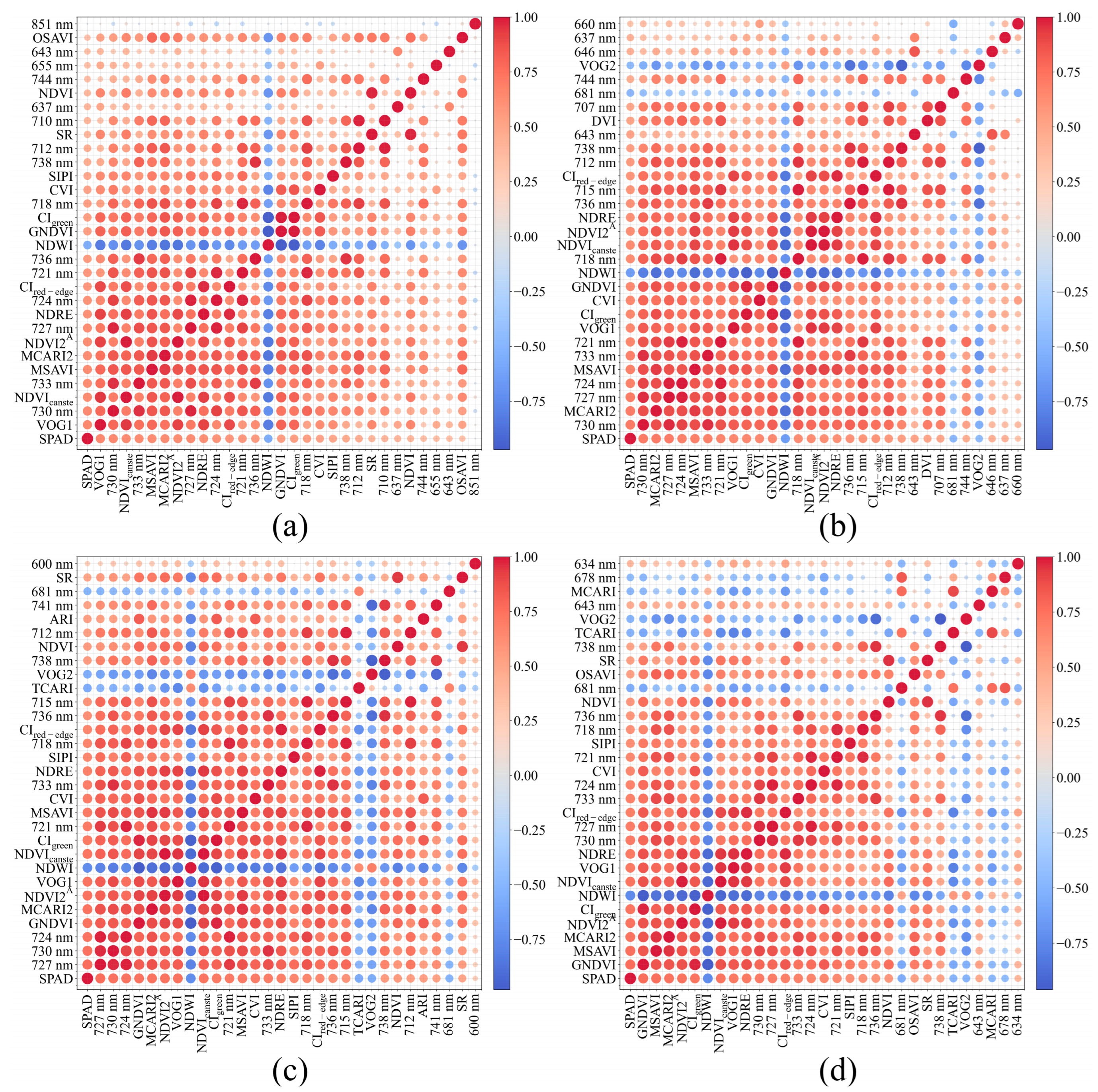

3.2. Screening Results of Spectral Data and Vegetation Indices

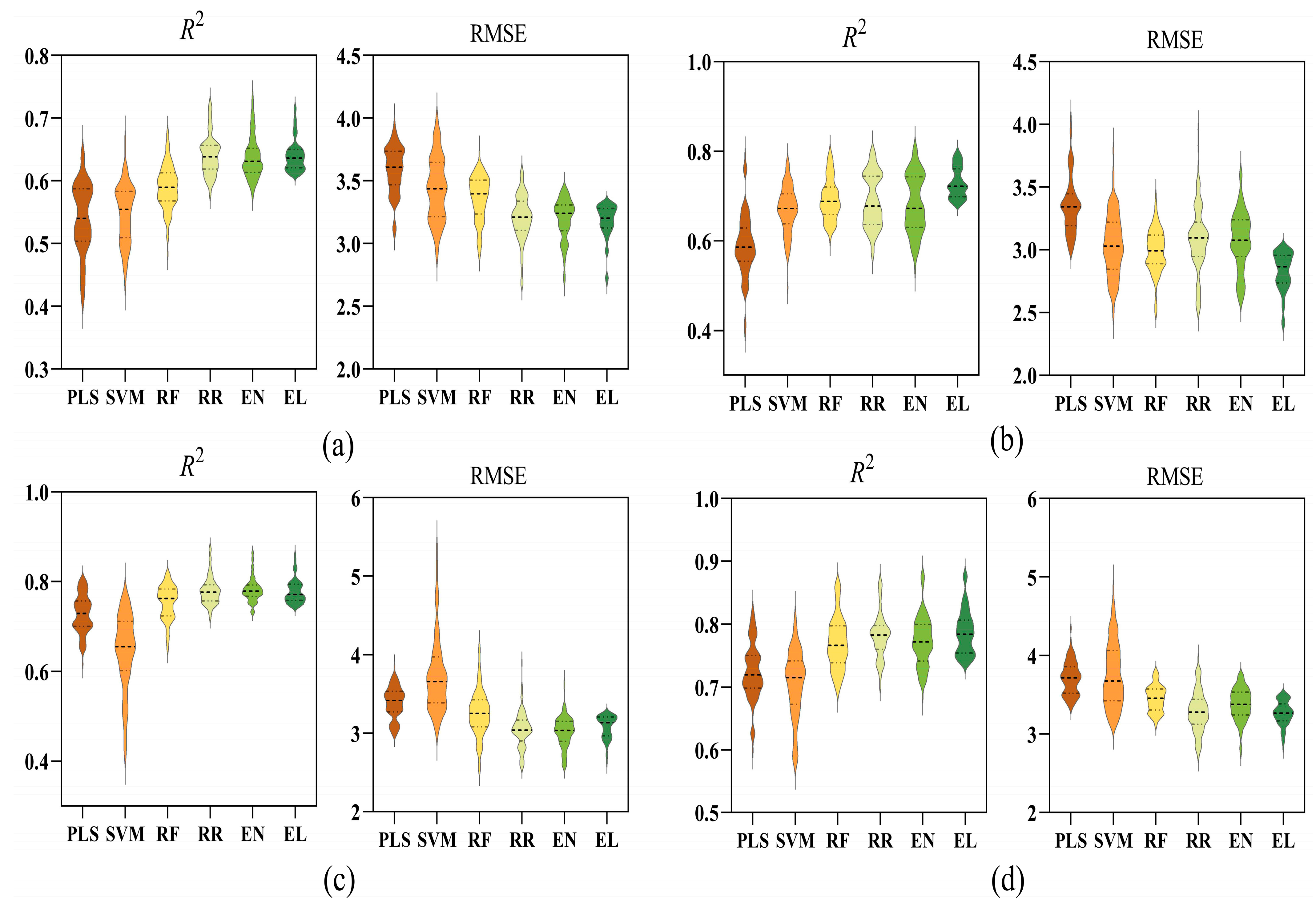

3.3. Estimation Performance of Six Different Models

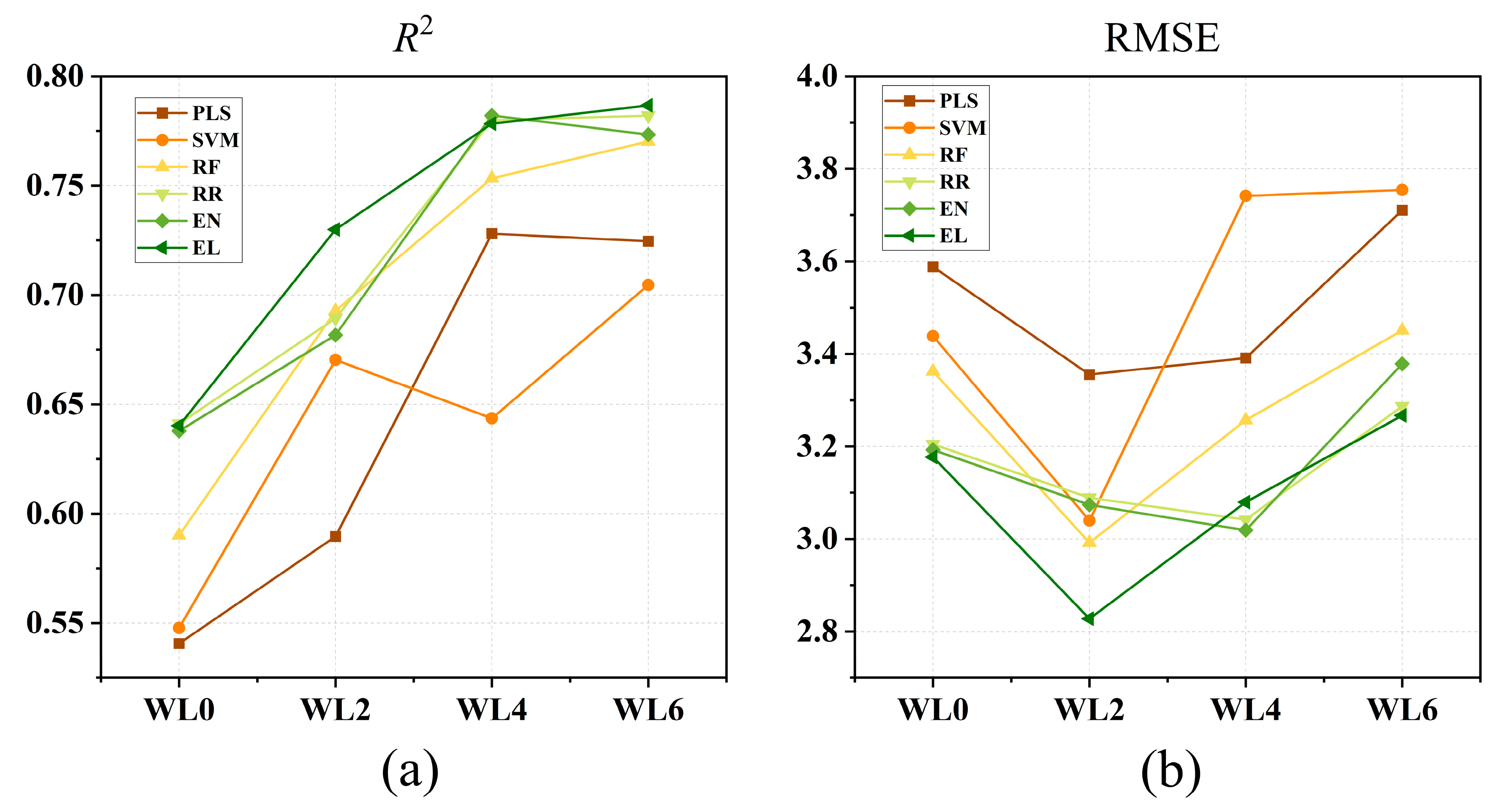

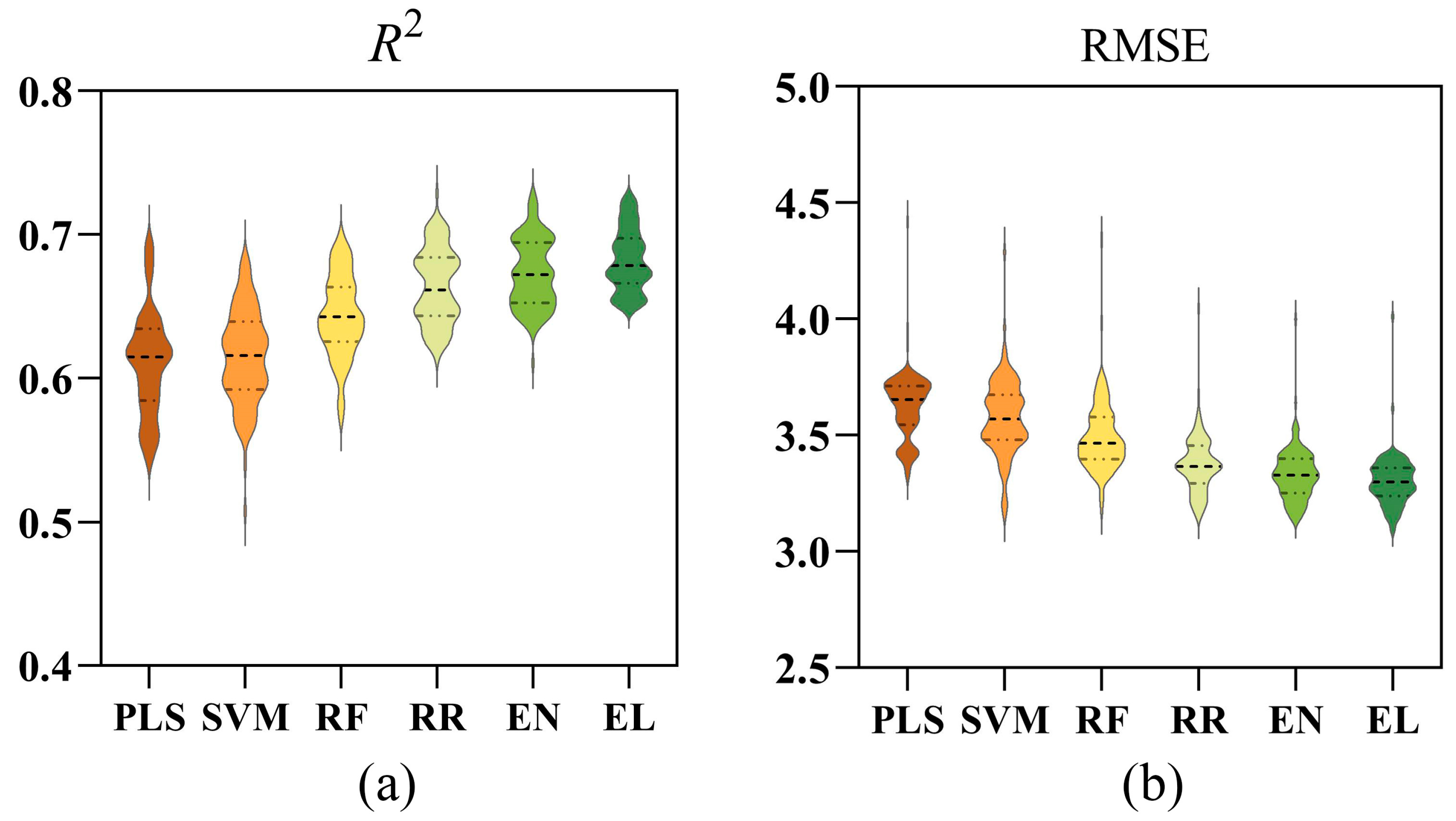

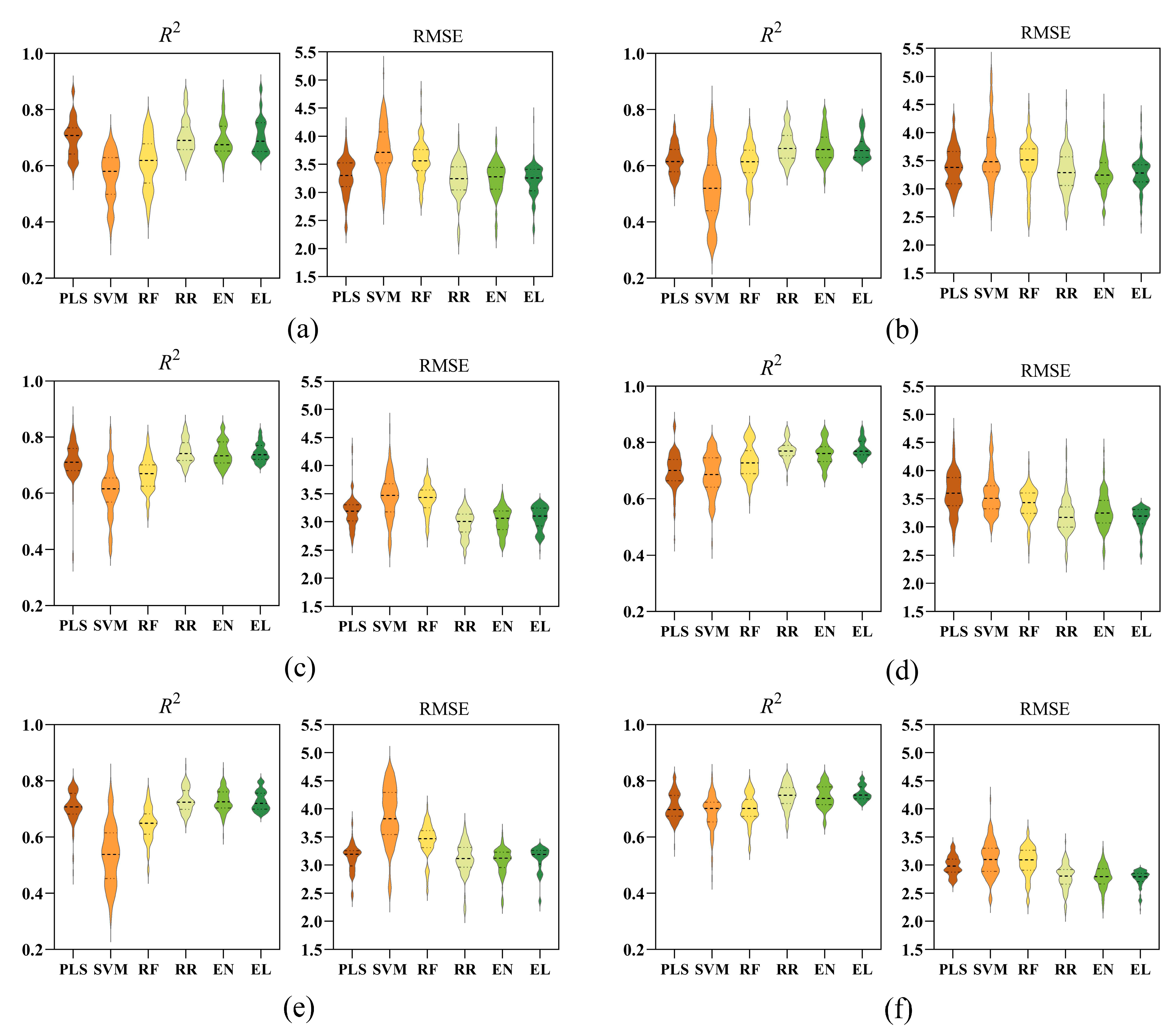

3.4. Comparison of Six Models Under Different Waterlogging Durations

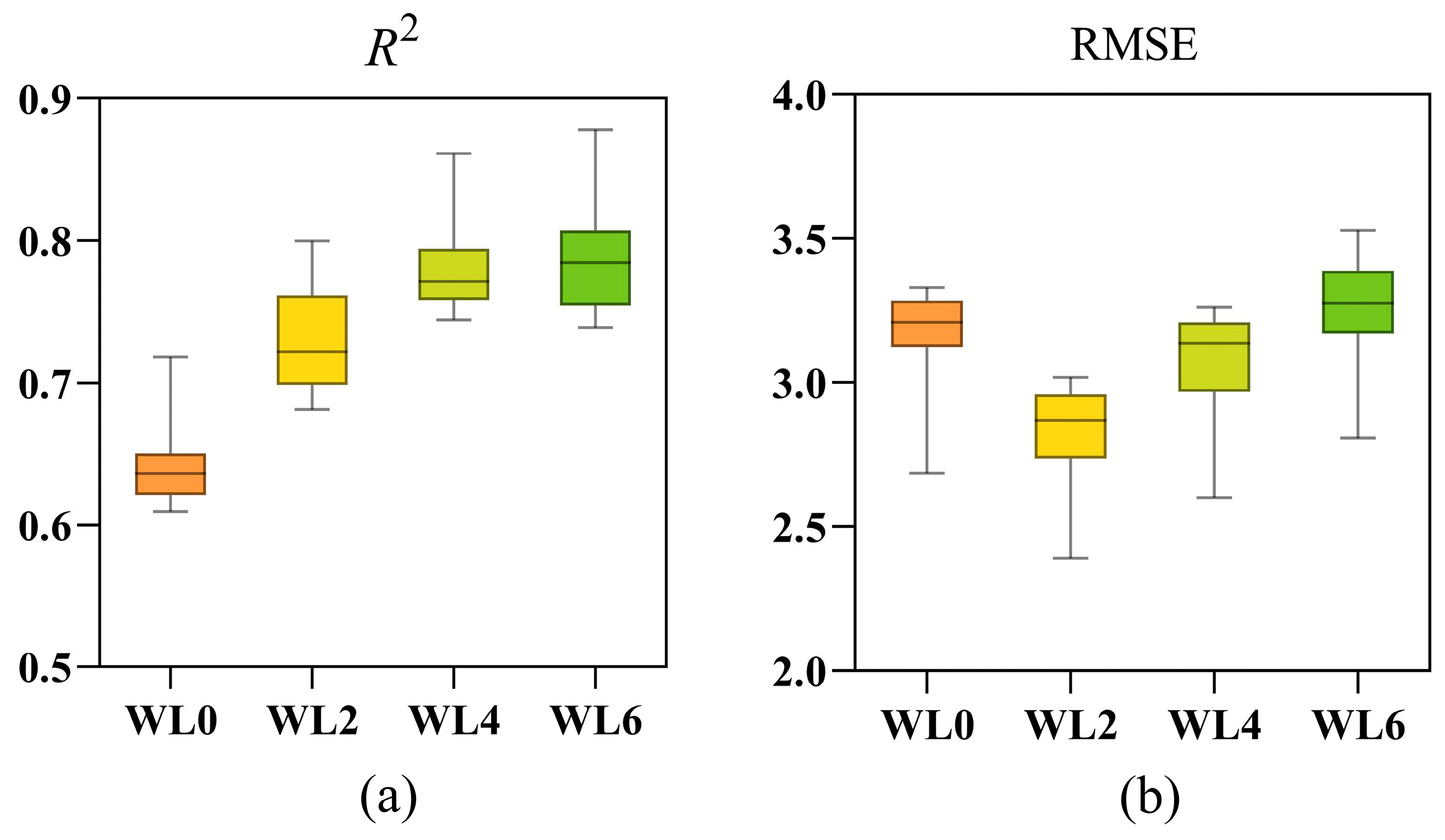

3.5. Effect of Waterlogging Durations on Model Performance

3.6. Model Training Results of Rapeseed Leaves Under Full-Cycle Waterlogging Stress (WLS)

3.7. Prediction Performance of Six Rapeseed Cultivars Under Different Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Prolonged WLS expanded sensitive features from the red-edge to green-red-edge areas and intensified its inverse correlation with the water index NDWI.

- (2)

- The EL model showed greater stability than single models when applied to various data from genotypes and WLS treatments. It also demonstrated higher prediction accuracy in most models.

- (3)

- EL model achieved its highest goodness-of-fit (R2) at the WL6, but its lowest prediction error (RMSE) in WL2.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wasim, A.; Bian, X.; Huang, F.; Zhi, X.; Cao, Y.; Gun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, N. Unveiling Root Growth Dynamics and Rhizosphere Microbial Responses to Waterlogging Stress in Rapeseed Seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 228, 110269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Kar, I.; Yadav, A.; Sahu, A. Exploring Waterlogging Challenges, Causes and Mitigating Strategies in Maize (Zea Mays L.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, L.; Nayatami, K.L.; Tamu, A.; Soe, I.; Sakagami, J.-I. Photosynthetic Function Analysis under Rhizosphere Anaerobic Conditions in Early-Stage Cassava. Photosynth. Res. 2025, 163, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, J.; Xie, L.; Xu, B.; Zhang, X. Physiological Mechanisms in Response to Waterlogging during Seedling Stage of Brassica Napus L. Acta Agron. Sin. 2024, 50, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhong, R.; Wei, J.; Luo, H.; Eyal, Y.; Jin, H.; Wu, L.; Liang, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Arabidopsis CHLOROPHYLLASE 1 Protects Young Leaves from Long-Term Photodamage by Facilitating FtsH-Mediated D1 Degradation in Photosystem II Repair. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1149–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xin, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A.; Wang, X. Integrated Physiological and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Insight into Leaf Coloration Variation in Cucumber. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoran, C.; Yingxue, L.; Fang, W.; Xiaochen, Z. Spectral Scale Effects on the Optical Estimation of Winter Wheat Leaf SPAD Value. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wicharuck, S.; Suang, S.; Chaichana, C.; Chromkaew, Y.; Mawan, N.; Soilueang, P.; Khongdee, N. The Implementation of the SPAD-502 Chlorophyll Meter for the Quantification of Nitrogen Content in Arabica Coffee Leaves. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, W.; Zhou, J.; Dai, M.; Sun, Q.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Gu, X. A Spectral Index for Estimating Grain Filling Rate of Winter Wheat Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 223, 109059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshkabilov, S.; Lee, A.; Sun, X.; Lee, C.W.; Simsek, H. Hyperspectral Imaging Techniques for Rapid Detection of Nutrient Content of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce Cultivars. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 181, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotukhina, A.; Machikhin, A.; Guryleva, A.; Gresis, V.; Kharchenko, A.; Dekhkanova, K.; Polyakova, S.; Fomin, D.; Nesterov, G.; Pozhar, V. Evaluation of Leaf Chlorophyll Content from Acousto-Optic Hyperspectral Data: A Multi-Crop Study. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. SPAD Monitoring of Saline Vegetation Based on Gaussian Mixture Model and UAV Hyperspectral Image Feature Classification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudu, B.; Rong, G.; Guga, S.; Li, K.; Zhi, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bao, Y. Retrieving SPAD Values of Summer Maize Using UAV Hyperspectral Data Based on Multiple Machine Learning Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, X.; Dong, Z.; Guo, W. Estimation of Biomass in Wheat Using Random Forest Regression Algorithm and Remote Sensing Data. Crop J. 2016, 4, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandler, H.; Brenning, A.; Samimi, C. Quantifying Dwarf Shrub Biomass in an Arid Environment: Comparing Empirical Methods in a High Dimensional Setting. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 158, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Cui, X.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, L.; Shao, G.; Niu, Y.; Huang, S. UAV Multispectral Remote Sensing for the Estimation of SPAD Values at Various Growth Stages of Maize under Different Irrigation Levels. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.I.; Lee, H.; Yang, J.-S.; Choi, J.-H.; Jung, D.-H.; Park, Y.J.; Park, J.-E.; Kim, S.M.; Park, S.H. Predicting Models for Plant Metabolites Based on PLSR, AdaBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM Algorithms Using Hyperspectral Imaging of Brassica Juncea. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, R.; Xiao, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zong, X.; Yang, T. Faba Bean Above-Ground Biomass and Bean Yield Estimation Based on Consumer-Grade Unmanned Aerial Vehicle RGB Images and Ensemble Learning. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1439–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, T.; Yu, D.; Teng, D.; Ge, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, G. Ensemble Machine-Learning-Based Framework for Estimating Total Nitrogen Concentration in Water Using Drone-Borne Hyperspectral Imagery of Emergent Plants: A Case Study in an Arid Oasis, NW China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N.; Chivkunova, O.B. Optical Properties and Nondestructive Estimation of Anthocyanin Content in Plant Leaves. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote Estimation of Canopy Chlorophyll Content in Crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L08403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincini, M.; Frazzi, E.; D’Alessio, P. A Broad-Band Leaf Chlorophyll Vegetation Index at the Canopy Scale. Precis. Agric. 2008, 9, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Feng, W.; Guo, T. Comparing Methods for Estimating Leaf Area Index by Multi-Angular Remote Sensing in Winter Wheat. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Quantitative Estimation of Chlorophyll-a Using Reflectance Spectra: Experiments with Autumn Chestnut and Maple Leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1994, 22, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M. Evaluation of Vegetation Indices and a Modified Simple Ratio for Boreal Applications. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughtry, C. Estimating Corn Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration from Leaf and Canopy Reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Niu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Huang, W. Estimating Chlorophyll Content from Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices: Modeling and Validation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008, 148, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntjr, E.; Rock, B. Detection of Changes in Leaf Water Content Using Near- and Middle-Infrared Reflectances. Remote Sens. Environ. 1989, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFEETERS, S.K. The Use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the Delineation of Open Water Features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.J.; Rodriguez, D.; Christensen, L.K.; Belford, R.; Sadras, V.O.; Clarke, T.R. Spectral and Thermal Sensing for Nitrogen and Water Status in Rainfed and Irrigated Wheat Environments. Precis. Agric. 2006, 7, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roujean, J.-L.; Breon, F.-M. Estimating PAR Absorbed by Vegetation from Bidirectional Reflectance Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 51, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Q. Reflectance Variation within the In-Chlorophyll Centre Waveband for Robust Retrieval of Leaf Chlorophyll Content. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.A.; Peñuelas, J.; Field, C.B. A Narrow-Waveband Spectral Index That Tracks Diurnal Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 41, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, G.A. Quantifying Chlorophylls and Caroteniods at Leaf and Canopy Scales. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 66, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of Leaf-Area Index from Quality of Light on the Forest Floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Fredeen, A.L.; Merino, J.; Field, C.B. Reflectance Indices Associated with Physiological Changes in Nitrogen- and Water-Limited Sunflower Leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broge, N.H.; Leblanc, E. Comparing Prediction Power and Stability of Broadband and Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices for Estimation of Green Leaf Area Index and Canopy Chlorophyll Density. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmann, J.E.; Rock, B.N.; Moss, D.M. Red Edge Spectral Measurements from Sugar Maple Leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, M.; El Ouni, M.; Salem, M.B. Waterlogging Affect the Development, Yield and Components, Chlorophyll Content and Chlorophyll Fluorescence of Six Bread Wheat Genotypes (Triticum Aestivum L.). Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 20, 647–657. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, S.; Di, L.; Zhang, C.; Deng, M.; Lin, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z. Estimating Crop Chlorophyll Content with Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices and the Hybrid Inversion Method. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 2923–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A.; Khurshid, K.S.; Staenz, K.; Schwarz, J.W. A Comparison of Hyperspectral Chlorophyll Indices for Wheat Crop Chlorophyll Content Estimation Using Laboratory Reflectance Measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2007, 45, 3063–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S.; Schweiger, A.K. Plant Spectra as Integrative Measures of Plant Phenotypes. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 2536–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; Windham, W.R.; Gholz, H.L. Exploring the Relationship between Reflectance Red Edge and Chlorophyll Concentration in Slash Pine Leaves. Tree Physiol. 1995, 15, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, P.-S.; Liu, S.-R. A Review of Plant Spectral Reflectance Response to Water Physiological Changes. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2016, 40, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Marusig, D.; Petruzzellis, F.; Tomasella, M.; Napolitano, R.; Altobelli, A.; Nardini, A. Correlation of Field-Measured and Remotely Sensed Plant Water Status as a Tool to Monitor the Risk of Drought-Induced Forest Decline. Forests 2020, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Guan, Q.; Lu, Z.; Lu, J. An Ensemble Modeling Framework for Distinguishing Nitrogen, Phosphorous and Potassium Deficiencies in Winter Oilseed Rape (Brassica Napus L.) Using Hyperspectral Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Gao, L.; Xu, X.; Wu, W.; Yang, G.; Meng, Y.; Feng, H.; Li, Y.; Xue, H.; Chen, T. Combining UAV Remote Sensing with Ensemble Learning to Monitor Leaf Nitrogen Content in Custard Apple (Annona Squamosa L.). Agronomy 2024, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, J.O.; Schulz-Streeck, T.; Piepho, H.-P. Genomic Selection Using Regularized Linear Regression Models: Ridge Regression, Lasso, Elastic Net and Their Extensions. BMC Proc. 2012, 6, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vegetation Index | Calculation Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anthocyanin Reflectance Index | [20] | |

| Chlorophyll Index | [21] | |

| [21] | ||

| Chlorophyll Vegetation Index | [22] | |

| Difference Vegetation Index | [23] | |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [24] | |

| Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | [25] | |

| Modified Simple Ratio | [26] | |

| Modified Chlorophyll Absorption Ratio Index | [27] | |

| [28] | ||

| Moisture Stress Index | [29] | |

| Normalized Difference Water Index | [30] | |

| Normalized Difference Red Edge Index | [31] | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [32] | |

| [33] | ||

| [33] | ||

| Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | [34] | |

| Photochemical Reflectance Index | [35] | |

| Ratio Vegetation Index | [36] | |

| Renormalized Difference Vegetation Index | [32] | |

| Simple Ratio | [37] | |

| Structure Insensitive Pigment Index | [38] | |

| Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption Ratio Index | [39] | |

| Triangular Vegetation Index | [39] | |

| Vogelmann Index | [40] | |

| [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, Y.; Peng, Y.; Song, H.; Jin, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ji, Y.; Ding, M. Combining Hyperspectral Imaging with Ensemble Learning for Estimating Rapeseed Chlorophyll Content Under Different Waterlogging Durations. Plants 2025, 14, 3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243713

Jin Y, Peng Y, Song H, Jin Y, Jiang L, Ji Y, Ding M. Combining Hyperspectral Imaging with Ensemble Learning for Estimating Rapeseed Chlorophyll Content Under Different Waterlogging Durations. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243713

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Ying, Yaoqi Peng, Haoyan Song, Yu Jin, Linxuan Jiang, Yishan Ji, and Mingquan Ding. 2025. "Combining Hyperspectral Imaging with Ensemble Learning for Estimating Rapeseed Chlorophyll Content Under Different Waterlogging Durations" Plants 14, no. 24: 3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243713

APA StyleJin, Y., Peng, Y., Song, H., Jin, Y., Jiang, L., Ji, Y., & Ding, M. (2025). Combining Hyperspectral Imaging with Ensemble Learning for Estimating Rapeseed Chlorophyll Content Under Different Waterlogging Durations. Plants, 14(24), 3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243713