Response of Lodging Resistance and Grain Yield to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations in Maize (Zea mays L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Grain Yield and Yield Components

2.2. Plant and Ear Height and Gravity Center Height

2.3. Stem–Leaf Angle and Leaf Orientation Value

2.4. Internode Traits and Aerial Root Layers

2.5. Stem Mechanical Properties

2.6. Stem Chemical Composition

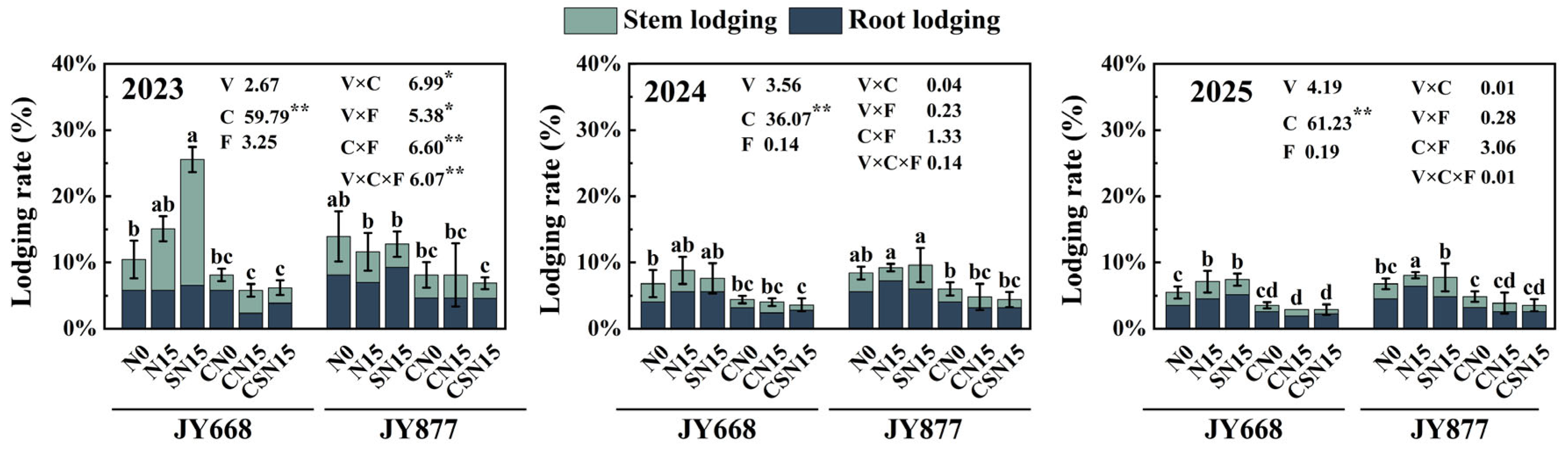

2.7. Lodging Rate

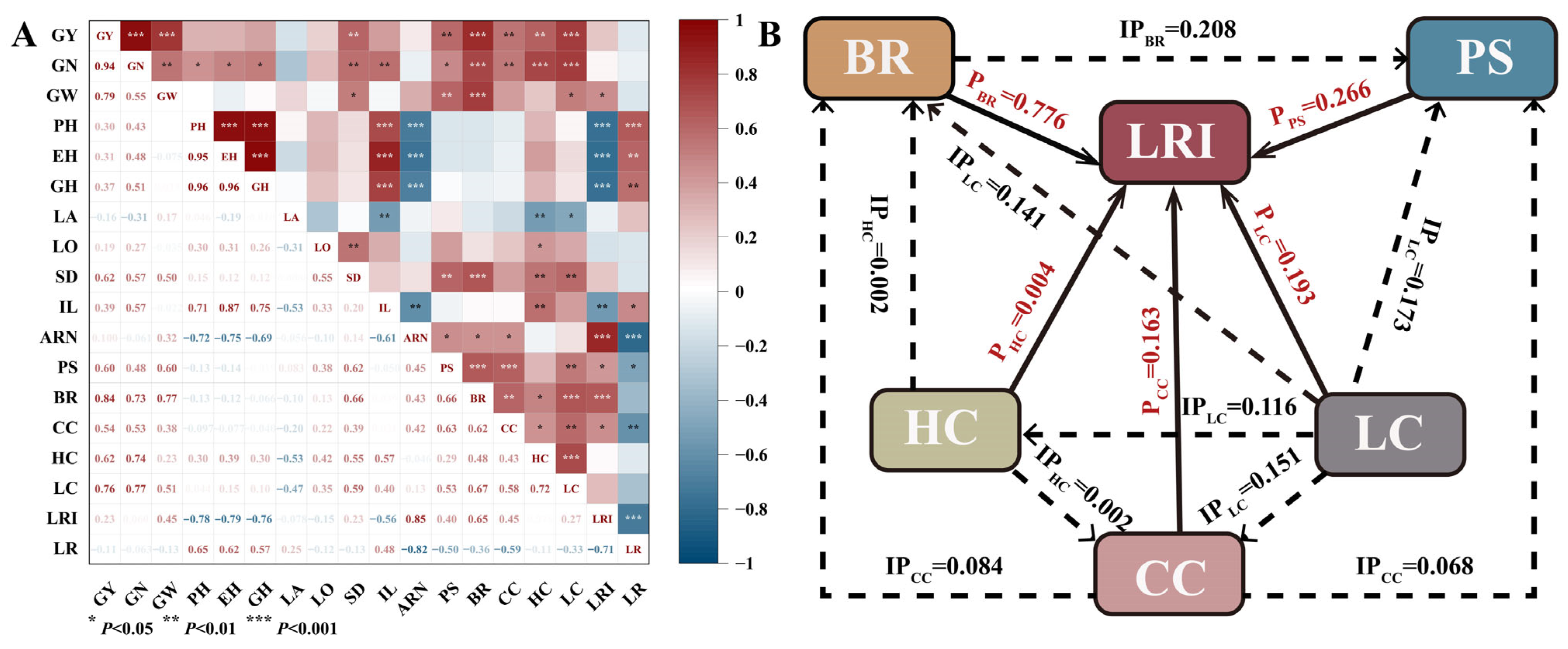

2.8. Correlation Analysis and Path Analysis

3. Discussion

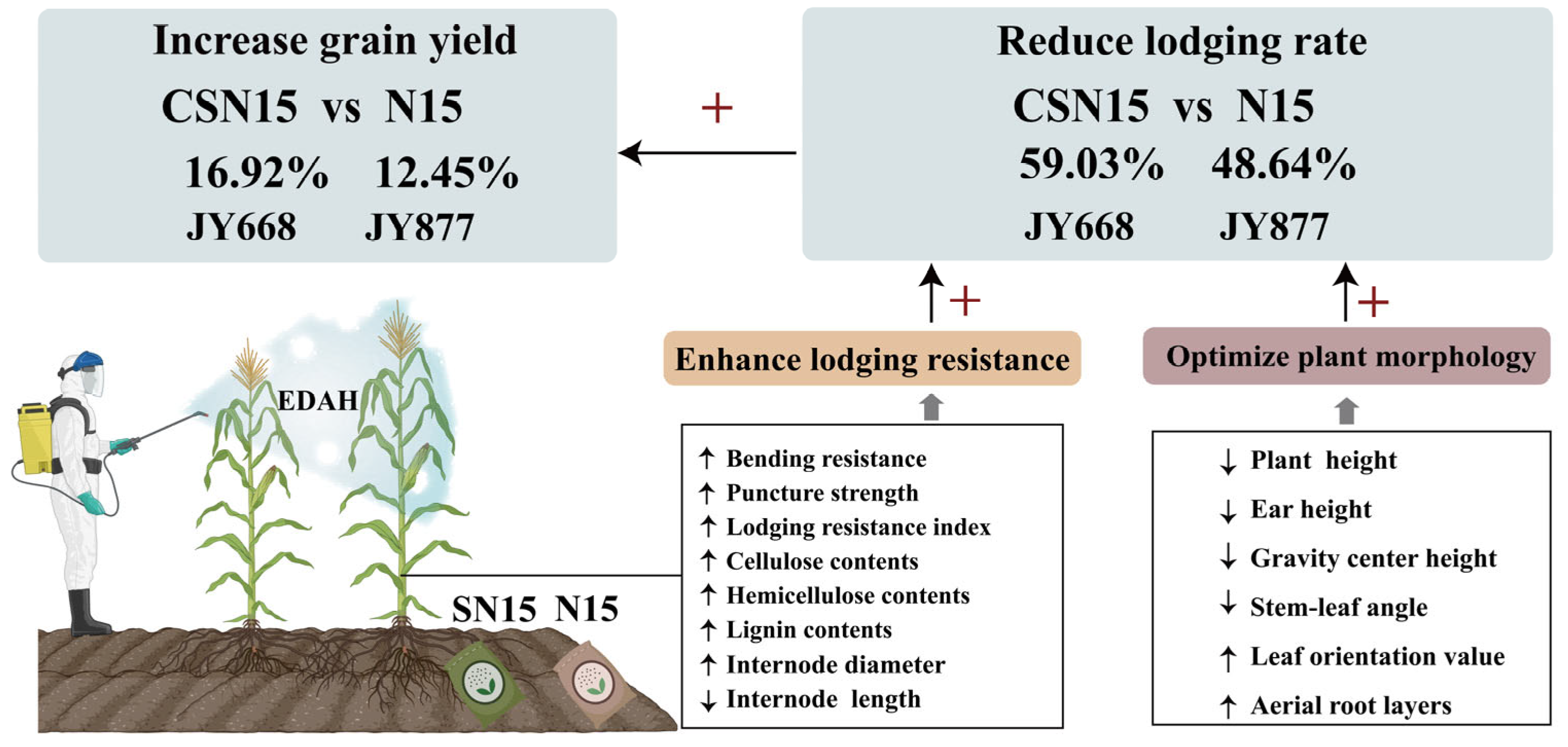

3.1. Maize Yield Response to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations

3.2. Plant Morphology Response to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations

3.3. Lodging Resistance Response to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Site

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Sampling and Measurements

4.3.1. Grain Yield and Its Components

4.3.2. Plant Morphology

4.3.3. Stem Mechanical Properties and Lodging Rate

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, N.; Pei, Y.; Peng, J.; Wang, Z. An Integrated Strategy Coordinating Endogenous and Exogenous Approaches to Alleviate Crop Lodging. Plant Stress 2023, 9, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Shen, R.; Li, X.; Ye, T.; Dong, J.; Fu, Y.; Yuan, W. A Twenty-Year Dataset of High-Resolution Maize Distribution in China. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, N.; Meng, Q.; Feng, P.; Qu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, D.L.; Müller, C.; Wang, P. China Can Be Self-Sufficient in Maize Production by 2030 with Optimal Crop Management. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gu, W.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Wei, S. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer and Chemical Regulation on Spring Maize Lodging Characteristics, Grain Filling and Yield Formation under High Planting Density in Heilongjiang Province, China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Batyrbek, M.; Ikram, K.; Ahmad, S.; Kamran, M.; Misbah; Khan, R.S.; Hou, F.; Han, Q. Nitrogen Management Improves Lodging Resistance and Production in Maize (Zea Mays L.) at a High Plant Density. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, M. Lodging Prevention in Cereals: Morphological, Biochemical, Anatomical Traits and Their Molecular Mechanisms, Management and Breeding Strategies. Field Crops Res. 2022, 289, 108733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, L.; Yahya, M.; Shah, S.M.A.; Nadeem, M.; Ali, A.; Ali, A.; Wang, J.; Riaz, M.W.; Rehman, S.; Wu, W.; et al. Improving Lodging Resistance: Using Wheat and Rice as Classical Examples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Xie, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Hou, P.; Ming, B.; Gou, L.; Li, S. Research Progress on Reduced Lodging of High-Yield and -Density Maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Duan, L. Plant Growth Regulator and Its Interactions with Environment and Genotype Affect Maize Optimal Plant Density and Yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 91, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.M.; Baker, C.J.; Hatley, D.; Dong, R.; Wang, X.; Blackburn, G.A.; Miao, Y.; Sterling, M.; Whyatt, J.D. Development and Application of a Model for Calculating the Risk of Stem and Root Lodging in Maize. Field Crops Res. 2021, 262, 108037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Peng, C.; Tan, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L. A Novel Plant Growth Regulator Improves the Grain Yield of High-Density Maize Crops by Reducing Stalk Lodging and Promoting a Compact Plant Type. Field Crops Res. 2021, 260, 107982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Pubu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Han, J. Optimal N Fertilizer Management Method for Improving Maize Lodging Resistance and Yields by Combining Controlled-Release Urea and Normal Urea. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 156, 127159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Huang, S. The Relationships between Maize (Zea Mays L.) Lodging Resistance and Yield Formation Depend on Dry Matter Allocation to Ear and Stem. Crop J. 2023, 11, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Meng, X.; Bian, S. Effects of Plant Growth Regulators and Nitrogen Management on Root Lodging Resistance and Grain Yield under High-Density Maize Crops. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Gu, S.; Xiao, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. In Situ Evaluation of Stalk Lodging Resistance for Different Maize (Zea Mays L.) Cultivars Using a Mobile Wind Machine. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Gou, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W. Effect of Leaf Removal on Photosynthetically Active Radiation Distribution in Maize Canopy and Stalk Strength. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Liu, F.; Li, X.; Yin, P.; Lan, T.; Feng, D.; Song, B.; Lei, E.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Ecological Factors Regulate Stalk Lodging within Dense Planting Maize. Field Crops Res. 2024, 317, 109529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Evers, J.; van der Werf, W.; Zhang, W.; Duan, L. Maize Yield and Quality in Response to Plant Density and Application of a Novel Plant Growth Regulator. Field Crops Res. 2014, 164, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Gao, Y.; Tian, B.; Ren, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, P. Effects of EDAH, a Novel Plant Growth Regulator, on Mechanical Strength, Stalk Vascular Bundles and Grain Yield of Summer Maize at High Densities. Field Crops Res. 2017, 200, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, C.J.; Kunduru, B.; Bokros, N.; Verges, V.; Porter, J.; Cook, D.D.; DeBolt, S.; McMahan, C.; Sekhon, R.S.; Robertson, D.J. Moving toward Short Stature Maize: The Effect of Plant Height on Maize Stalk Lodging Resistance. Field Crops Res. 2023, 300, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Kong, F.; Liu, Q.; Lan, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ou, Q.; Chen, L.; Kessel, G.; Kempenaar, C.; et al. Maize Basal Internode Development Significantly Affects Stalk Lodging Resistance. Field Crops Res. 2022, 286, 108611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Qu, S.; Huang, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L. Improving Maize Grain Yield by Formulating Plant Growth Regulator Strategies in North China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, D.; Cui, T.; Huang, S.; Wang, P. Morphological and Mechanical Variables Associated with Lodging in Maize (Zea Mays L.). Field Crops Res. 2021, 269, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Li, Z.; Shah, F.; Wu, W. Optimizing Biomass Allocation for Optimum Balance of Seed Yield and Lodging Resistance in Rapeseed. Field Crops Res. 2024, 316, 109493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Qv, S.; Zhu, A.; Li, W. Effects of “Yuhuangjin” Spraying on Lodging Resistance and Yield of Summer Maize. J. Maize Sci. 2021, 29, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Its Link to Canopy Photosynthesis in Maize from Continuous Ground Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Gou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, M.; Yao, H.; Tian, J.; Zhang, W. Effects of Light Intensity within the Canopy on Maize Lodging. Field Crops Res. 2016, 188, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Kamran, M.; Ali, S.; Bilegjargal, B.; Cai, T.; Ahmad, S.; Meng, X.; Su, W.; Liu, T.; Han, Q. Uniconazole Application Strategies to Improve Lignin Biosynthesis, Lodging Resistance and Production of Maize in Semiarid Regions. Field Crops Res. 2018, 222, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, W.; Jin, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Nitrogen Regulates Stem Lodging Resistance by Breaking the Balance of Photosynthetic Carbon Allocation in Wheat. Field Crops Res. 2023, 296, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, Q.; Kong, F.; Du, L.; Zhou, F.; Shi, H.; Ke, Y.; Liu, Q.; Feng, D.; et al. Non-Structural Carbohydrates in Maize with Different Nitrogen Tolerance Are Affected by Nitrogen Addition. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, D.; Zhang, S.; Gu, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Huang, S. Optimizing Root System Architecture to Improve Root Anchorage Strength and Nitrogen Absorption Capacity under High Plant Density in Maize. Field Crops Res. 2023, 303, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yan, Y.; Gu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Sheng, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Huang, S. Lodging Resistance in Maize: A Function of Root–Shoot Interactions. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 132, 126393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, G.; Shah, S.; Ren, H.; Ren, B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B. The Potential of EDAH in Promoting Kernel Formation and Grain Yield in Summer Maize. Field Crops Res. 2024, 319, 109655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.K.; Tahir, M.M.; Rahim, N. Effect of N Fertilizer Source and Timing on Yield and N Use Efficiency of Rainfed Maize (Zea Mays L.) in Kashmir–Pakistan. Geoderma 2013, 195–196, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fu, P.; Cheng, G.; Lu, W.; Lu, D. Delaying Application Time of Slow-Release Fertilizer Increases Soil Rhizosphere Nitrogen Content, Root Activity, and Grain Yield of Spring Maize. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Geng, J. Improving Crop Yields, Nitrogen Use Efficiencies, and Profits by Using Mixtures of Coated Controlled-Released and Uncoated Urea in a Wheat-Maize System. Field Crops Res. 2017, 205, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.; An, L.; Zhang, S.; Feng, J.; Sun, D.; Yao, Y.; Shen, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M. The Long-Term Effects of Microplastics on Soil Organomineral Complexes and Bacterial Communities from Controlled-Release Fertilizer Residual Coating. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Song, X.; Zheng, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, Q.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Gao, F.; Tian, H.; et al. The Controlled-Release Nitrogen Fertilizer Driving the Symbiosis of Microbial Communities to Improve Wheat Productivity and Soil Fertility. Field Crops Res. 2022, 289, 108712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Sui, C.; Liu, Z.; Geng, J.; Tian, X.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, M. Long-Term Effects of Controlled-Release Urea on Crop Yields and Soil Fertility under Wheat–Corn Double Cropping Systems. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1703–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cheng, G.; Li, L.; Lu, D.; Lu, W. Effects of Slow-Released Fertilizer on Maize Yield, Biomass Production, and Source-Sink Ratio at Different Densities. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Yue, S.; Hou, P.; Cui, Z.; Chen, X. Improving Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency Simultaneously for Maize and Wheat in China: A Review. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Gao, S.; Fan, Y.; Li, L.; Ming, B.; Wang, K.; Xie, R.; Hou, P.; Li, S. Traits of Plant Morphology, Stalk Mechanical Strength, and Biomass Accumulation in the Selection of Lodging-Resistant Maize Cultivars. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 117, 126073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, C. Ridge-Furrow with Plastic Film Mulching System Decreases the Lodging Risk for Summer Maize Plants under Different Nitrogen Fertilization Rates and Varieties in Dry Semi-Humid Areas. Field Crops Res. 2021, 263, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Blaylock, A.D.; Chen, X. Mixture of Controlled Release and Normal Urea to Optimize Nitrogen Management for High-Yielding (>15 Mg ha−1) Maize. Field Crops Res. 2017, 204, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lai, H.; Bi, C.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, D. Effects of Paclobutrazol Application on Plant Architecture, Lodging Resistance, Photosynthetic Characteristics, and Peanut Yield at Different Single-Seed Precise Sowing Densities. Crop J. 2023, 11, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cheng, G.; Lu, W.; Lu, D. Differences of Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency under Different Applications of Slow Release Fertilizer in Spring Maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, B.; KuShaari, K.; Man, Z.B.; Basit, A.; Thanh, T.H. Review on Materials & Methods to Produce Controlled Release Coated Urea Fertilizer. J. Control. Release 2014, 181, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Yue, X.; Liang, X.; Hong, Y.; Wang, F.; Hu, C.; Liu, R. Controlled-Release Fertilizer Improving Paddy Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency by Reducing Soil Residual Nitrogen and Leaching Losses in the Yellow River Irrigation Area. Plants 2025, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalk, P.M.; Craswell, E.T.; Polidoro, J.C.; Chen, D. Fate and Efficiency of 15N-Labelled Slow- and Controlled-Release Fertilizers. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2015, 102, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Xie, R.; Liu, X.; Niu, X.; Hou, P.; Wang, K.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Lodging-Related Stalk Characteristics of Maize Varieties in China since the 1950s. Crop Sci. 2014, 54, 2805–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Abbas, A.; Yildirim, M.; Shah, A.A.; Ahmad, M.I.; Wang, Z.; Sun, W.; Song, Y. Combating Dual Challenges in Maize Under High Planting Density: Stem Lodging and Kernel Abortion. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñera-Chavez, F.J.; Berry, P.M.; Foulkes, M.J.; Molero, G.; Reynolds, M.P. Avoiding Lodging in Irrigated Spring Wheat. II. Genetic Variation of Stem and Root Structural Properties. Field Crops Res. 2016, 196, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, R.; Guo, R.; Guo, G.; Ren, X.; Chen, X.; Jia, Z. Impact of Straw and Its Derivatives on Lodging Resistance and Yield of Maize (Zea Mays L.) under Rainfed Areas. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 153, 127055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Guo, T.; Zhao, J.; Guan, Z.; Liu, K. Identification and Characterization of a New Dwarf Locus DS-4 Encoding an Aux/IAA7 Protein in Brassica Napus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 1435–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ma, B.-L. Erect–Leaf Posture Promotes Lodging Resistance in Oat Plants under High Plant Population. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 103, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, D.; Liu, X.; She, H.; Ruan, R.; Yang, H.; Yi, Z.; Wu, D. Effects of Uniconazole on the Lignin Metabolism and Lodging Resistance of Culm in Common Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum M.). Field Crops Res. 2015, 180, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Yang, D.; Luo, Y.; Pang, D.; Xu, X.; Li, W.; et al. Manipulation of Lignin Metabolism by Plant Densities and Its Relationship with Lodging Resistance in Wheat. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Jia, Z.; Ma, X.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y. Characterising the Morphological Characters and Carbohydrate Metabolism of Oat Culms and Their Association with Lodging Resistance. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistie, E.; McDonald, A.G. Effect of Cell Wall Compositions on Lodging Resistance of Cereal Crops: Review. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, T.; Ding, R.; Han, Q. Mepiquat Chloride Application Increases Lodging Resistance of Maize by Enhancing Stem Physical Strength and Lignin Biosynthesis. Field Crops Res. 2018, 224, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Wu, X.; Liu, T.; Ding, R.; Han, Q. Application of Paclobutrazol: A Strategy for Inducing Lodging Resistance of Wheat through Mediation of Plant Height, Stem Physical Strength, and Lignin Biosynthesis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 29366–29378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Fu, C.; Liang, C.; Ni, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, M.; Ou, L. Crop Lodging and The Roles of Lignin, Cellulose, and Hemicellulose in Lodging Resistance. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ning, F.; Cao, Y.; Liao, S.; Wang, P.; Huang, S. Shortening Internodes Near Ear: An Alternative to Raise Maize Yield. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, F.; Ren, B.; Dong, S.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J. Lignin Metabolism Regulates Lodging Resistance of Maize Hybrids under Varying Planting Density. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2077–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Hu, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Ren, X. Large-Scale Screening of Diverse Barely Lignocelluloses for Simultaneously Upgrading Biomass Enzymatic Saccharification and Plant Lodging Resistance Coupled with near-Infrared Spectroscopic Assay. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 194, 116324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Variety | Treatment | Row Number | Grains Per Row | Grain Number Per Ear | 1000-Grain Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | JY668 | N0 | 14.67c | 28.25b | 414.33c | 252.46c |

| N15 | 15.33ab | 30.58ab | 468.94bc | 267.95b | ||

| SN15 | 14.67c | 33.83a | 496.17b | 284.56a | ||

| CN0 | 14.67c | 27.42b | 402.11c | 255.56c | ||

| CN15 | 15.33ab | 31.25ab | 479.17bc | 270.28ab | ||

| CSN15 | 16.67a | 30.94ab | 515.11a | 278.38ab | ||

| JY877 | N0 | 15.33ab | 27.69b | 424.58c | 264.13b | |

| N15 | 16.44a | 30.86ab | 507.67ab | 274.66ab | ||

| SN15 | 16.22a | 31.86ab | 516.84a | 274.51ab | ||

| CN0 | 15.56ab | 26.53b | 412.94c | 266.14b | ||

| CN15 | 16.00a | 31.89ab | 510.24a | 276.24ab | ||

| CSN15 | 15.33ab | 33.75a | 517.33a | 286.37a | ||

| 2024 | JY668 | N0 | 13.78b | 29.33b | 404.15bc | 262.28c |

| N15 | 14.22a | 32.04a | 455.64ab | 273.79b | ||

| SN15 | 14.44a | 31.37ab | 453.13ab | 300.66a | ||

| CN0 | 13.56b | 29.15b | 395.17c | 262.73c | ||

| CN15 | 13.44b | 34.04a | 457.63ab | 280.60ab | ||

| CSN15 | 14.22a | 33.70a | 479.34a | 289.19ab | ||

| JY877 | N0 | 13.67b | 29.85b | 407.98bc | 264.02c | |

| N15 | 13.22b | 32.93a | 435.35b | 289.82ab | ||

| SN15 | 14.00a | 33.33a | 466.67ab | 284.34ab | ||

| CN0 | 14.00a | 28.63b | 400.81bc | 264.18c | ||

| CN15 | 14.00a | 33.15a | 464.07ab | 280.13ab | ||

| CSN15 | 14.22a | 33.82a | 480.92a | 294.73a | ||

| 2025 | JY668 | N0 | 15.40c | 35.10b | 540.20d | 231.10b |

| N15 | 15.00c | 39.33a | 587.33c | 239.08b | ||

| SN15 | 15.40c | 39.87a | 610.33c | 266.90a | ||

| CN0 | 16.40b | 28.57d | 467.93e | 231.95b | ||

| CN15 | 15.40c | 38.77b | 596.00c | 227.76b | ||

| CSN15 | 16.20b | 40.53a | 656.40b | 266.73a | ||

| JY877 | N0 | 16.60b | 33.43c | 555.00d | 218.11c | |

| N15 | 16.00b | 36.97b | 607.93c | 253.28ab | ||

| SN15 | 17.00a | 39.27a | 667.67a | 271.60a | ||

| CN0 | 16.60b | 32.80c | 550.74d | 208.52c | ||

| CN15 | 16.80b | 36.33b | 611.07c | 236.05b | ||

| CSN15 | 18.20a | 37.07b | 674.00a | 254.70ab | ||

| ANOVA | ||||||

| Years (Y) | 2023 | 15.52b | 30.40c | 472.12b | 270.94b | |

| 2024 | 13.90c | 31.78b | 441.74c | 278.87a | ||

| 2025 | 16.25a | 36.50a | 593.72a | 247.15c | ||

| Variety (V) | JY668 | 14.93b | 33.00a | 493.28b | 263.44b | |

| JY877 | 15.51a | 32.79b | 511.77a | 264.53a | ||

| Fertilization (F) | N0 | 15.02b | 29.73c | 447.99c | 248.43c | |

| N15 | 15.10a | 34.01a | 515.09b | 264.14b | ||

| SN15 | 15.55a | 34.94a | 544.49a | 279.39a | ||

| Chemical regulation (C) | C0 | 15.08b | 33.10a | 501.11b | 265.18a | |

| C | 15.37a | 32.68b | 503.94a | 262.79b | ||

| Years (Y) | 145.96 ** | 350.63 ** | 349.42 ** | 397.35 ** | ||

| Varieties (V) | 27.27 ** | 0.94 | 12.69 ** | 5.25 * | ||

| Chemical regulation (C) | 7.54 ** | 4.33 * | 0.72 | 2.76 | ||

| Fertilization (F) | 7.45 ** | 247.01 ** | 122.57 ** | 425.74 ** | ||

| Y × V | 12.23 ** | 3.97 * | 3.73 * | 3.83 * | ||

| Y × C | 4.18 * | 10.58 ** | 0.24 | 1.33 | ||

| Y × F | 2.29 | 6.17 ** | 5.52 ** | 23.28 ** | ||

| V × C | 0.14 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.32 | ||

| V × F | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.16 | 13.54 ** | ||

| C × F | 1.57 | 10.96 ** | 4.48 * | 2.46 | ||

| Y × V × C | 5.66 ** | 5.73 ** | 0.30 | 3.35 * | ||

| Y × V × F | 2.27 | 5.89 ** | 0.97 | 15.46 ** | ||

| Y × C × F | 0.49 | 1.17 | 1.40 | 3.96 ** | ||

| V × C × F | 2.30 | 2.53 | 2.77 | 9.08 ** | ||

| Y × V × C × F | 2.36 | 8.12 ** | 1.23 | 2.99 | ||

| ANOVA | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDW (g) | TIL (cm) | TSD (mm) | LDW (g/cm) | TDW (g) | TIL (cm) | TSD (mm) | LDW (g/cm) | TDW (g) | TIL (cm) | TSD (mm) | LDW (g/cm) | |||

| Variety (V) | JY668 | 5.76a | 12.55b | 24.27b | 0.46a | 4.11a | 9.16a | 22.20b | 0.45a | 4.11a | 9.16a | 22.20b | 0.45a | |

| JY877 | 5.50b | 12.65a | 24.42a | 0.43b | 3.76b | 8.47b | 25.81a | 0.44b | 7.12a | 9.6a | 28.06a | 0.78a | ||

| Fertilization (F) | N0 | 4.47c | 12.02c | 23.55c | 0.37c | 2.91c | 7.95c | 20.18c | 0.37b | 4.78c | 6.83b | 21.95c | 0.70b | |

| N15 | 5.68b | 12.55b | 24.19b | 0.46b | 4.13b | 8.77b | 25.08b | 0.48a | 5.55b | 6.78c | 26.74b | 0.82a | ||

| SN15 | 6.73a | 13.23a | 25.30a | 0.51a | 4.77a | 9.73a | 26.75a | 0.49b | 6.77a | 10.72a | 28.73a | 0.64b | ||

| Chemical regulation (C) | C0 | 4.98b | 12.88a | 23.87b | 0.39b | 3.63b | 9.26a | 23.41b | 0.39c | 5.28b | 8.67a | 24.56b | 0.59b | |

| C | 6.27a | 12.32b | 24.82a | 0.51a | 4.24a | 8.37b | 24.6a | 0.50a | 6.12a | 7.55b | 27.05a | 0.85a | ||

| F-value | ||||||||||||||

| Varieties (V) | 1.71 | 0.32 | 1.01 | 1.46 | 0.85 | 5.32 * | 47.45 ** | 0.01 | 131.88 ** | 203.76 ** | 346.506 ** | 0.00 | ||

| Chemical regulation (C) | 41.74 ** | 10.23 ** | 43.68 ** | 41.67 ** | 2.67 | 8.86 ** | 5.13 * | 5.58 * | 11.51 ** | 28.94 ** | 106.598 ** | 95.09 ** | ||

| Fertilization (F) | 42.98 ** | 15.80 ** | 50.52 ** | 18.47 ** | 8.46 ** | 11.92 ** | 56.60 ** | 3.03 | 21.99 ** | 156.02 ** | 276.267 ** | 3.35 | ||

| V × C | 1.42 | 0.06 | 7.87 * | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 7.51 * | 3.48 | 7.343 * | 0.00 | ||

| V × F | 1.47 | 0.43 | 10.76 ** | 0.80 | 2.54 | 3.34 | 12.90 ** | 0.77 | 5.42 * | 1.82 | 5.319 * | 0.00 | ||

| C × F | 5.43 * | 0.86 | 14.7 ** | 3.32 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 1.29 | 0.03 | 4.47 * | 0.19 | 3.732 * | 14.02 ** | ||

| V × C × F | 0.82 | 0.44 | 11.54 ** | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 10.889 ** | 0.00 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Liang, Y.; You, G.; Guo, J.; Lu, D.; Li, G. Response of Lodging Resistance and Grain Yield to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations in Maize (Zea mays L.). Plants 2025, 14, 3707. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233707

Wang Y, Wang Y, Jiang C, Liang Y, You G, Guo J, Lu D, Li G. Response of Lodging Resistance and Grain Yield to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations in Maize (Zea mays L.). Plants. 2025; 14(23):3707. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233707

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuru, Yifei Wang, Chenyang Jiang, Yuwen Liang, Genji You, Jian Guo, Dalei Lu, and Guanghao Li. 2025. "Response of Lodging Resistance and Grain Yield to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations in Maize (Zea mays L.)" Plants 14, no. 23: 3707. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233707

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, Y., Jiang, C., Liang, Y., You, G., Guo, J., Lu, D., & Li, G. (2025). Response of Lodging Resistance and Grain Yield to EDAH and Different Fertilization Combinations in Maize (Zea mays L.). Plants, 14(23), 3707. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233707