Molecular Mechanisms of the Phytohormone–Heat Shock Protein Pathway in Regulating Plant Thermotolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

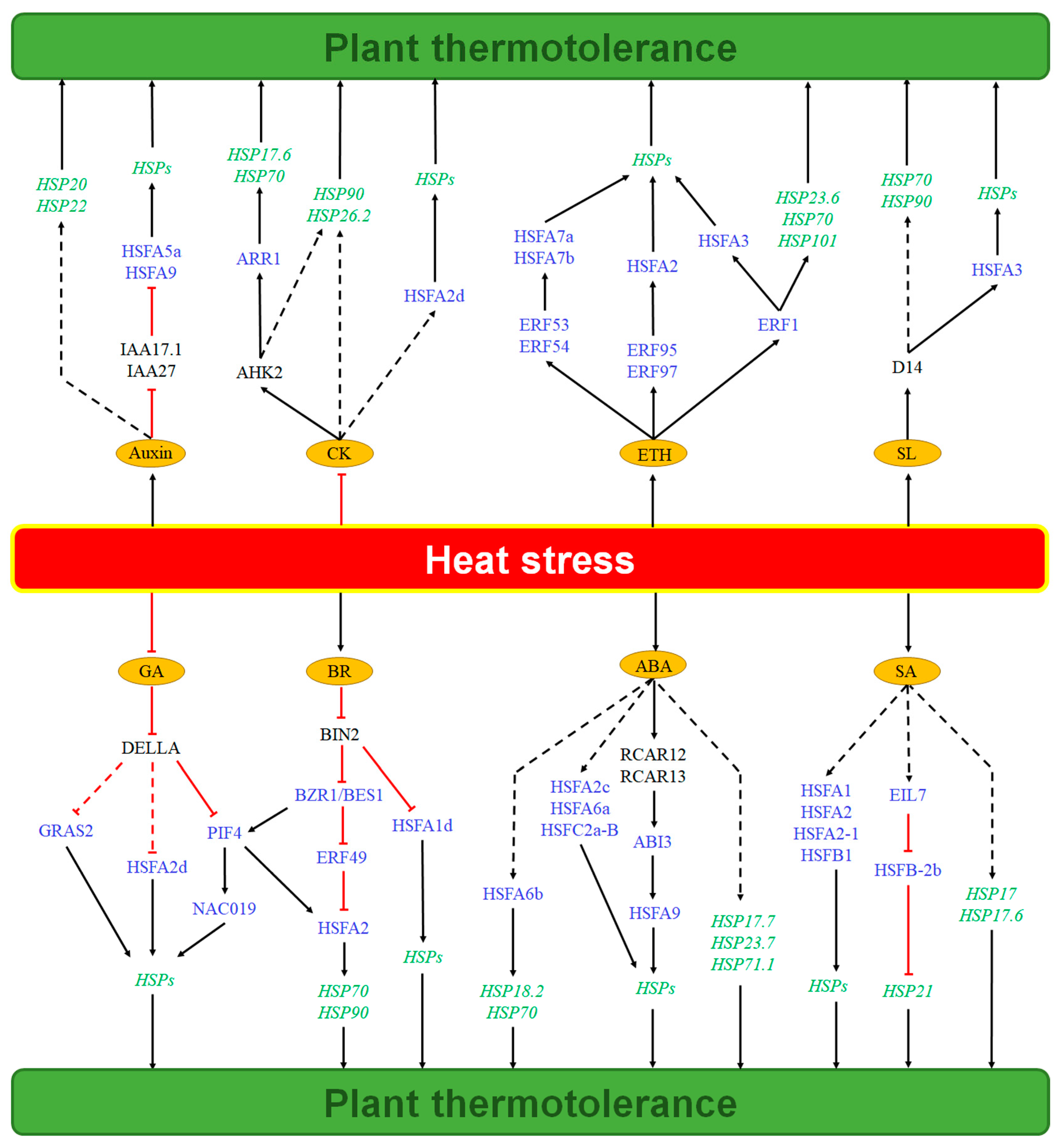

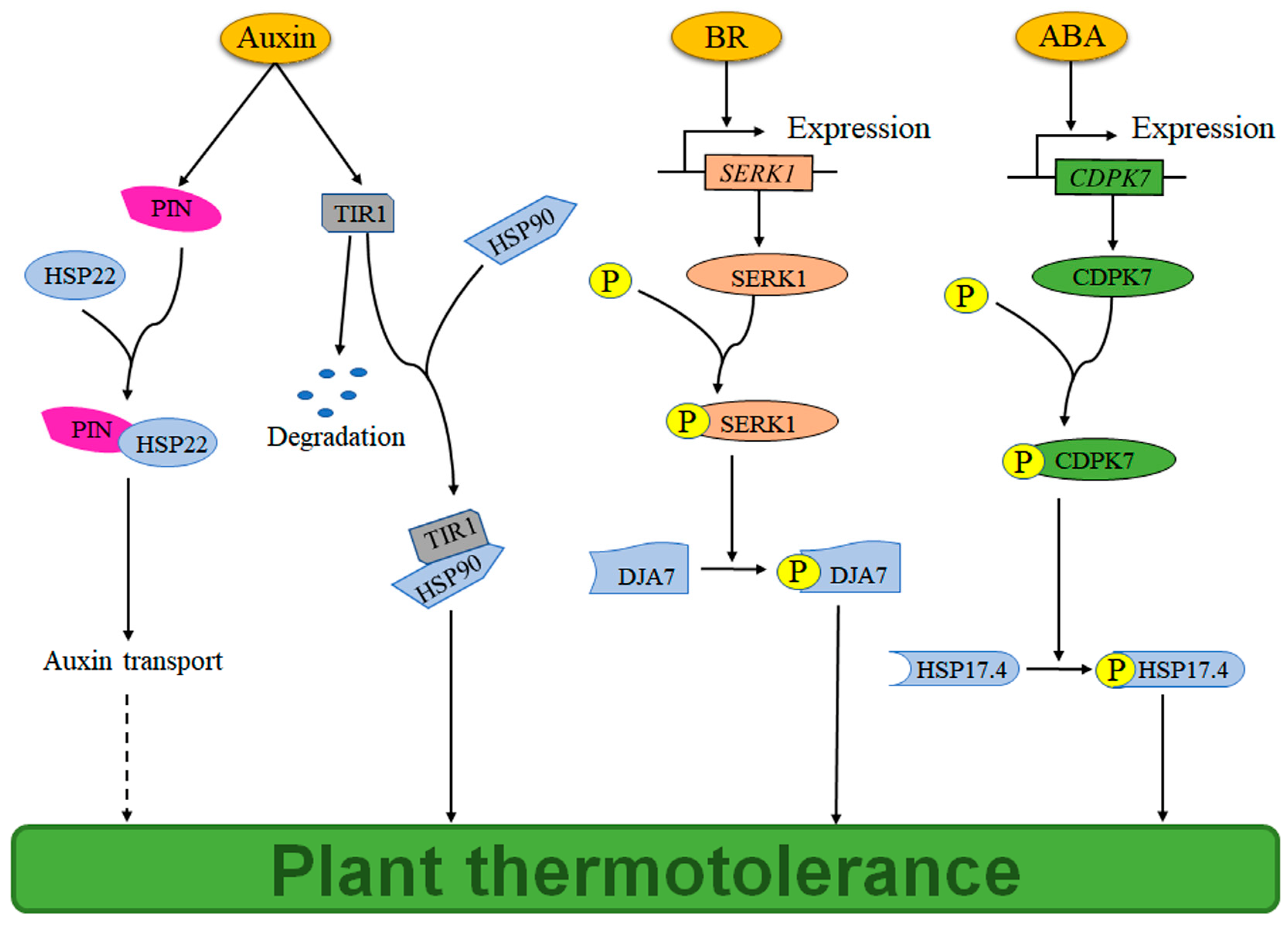

2. The Auxin–HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

3. The GA-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

4. The CK-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

5. The ABA-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

6. The BR-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

7. The SA-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

8. The ETH-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

9. The SL-HSP Pathway Regulates Plant Thermotolerance

10. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jung, M.P.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, S.G.; Park, H.H. Effect of climate change on the occurrence of overwintered moths of orchards in South Korea. Entomol. Res. 2013, 43, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J. IPCC, 2023: Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2024, 50, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Z. Heat stress-induced decapping of WUSCHEL mRNA enhances stem cell thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Zhao, S.; Tu, Y.; Liu, E.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhai, S.; Qi, J.; Wu, C.; et al. Proteasome resides in and dismantles plant heat stress granules constitutively. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 3320–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenbach, S.B.; DuPont, F.M.; Kothari, K.M.; Chan, R.; Johnson, E.L.; Lieu, D. Temperature, water and fertilizer influence the timing of key events during grain development in a US spring wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 2003, 37, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Du, Y.; Zeng, M.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zeng, Y. Relationship between chalkiness and the structural and physicochemical properties of rice starch at different nighttime temperatures during the early grain-filling stage. Foods 2024, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gu, X.; Lu, W.; Lu, D. Multiomics analysis of kernel development in response to short-term heat stress at the grain formation stage in waxy maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6291–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, S.; Zoong-Lwe, Z.S.; Gandhi, N.; Welti, R.; Fallen, B.; Smith, J.R.; Rustgi, S. Comparative lipidomic analysis reveals heat stress responses of two soybean genotypes differing in temperature sensitivity. Plants 2020, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lobell, Y.D.B.; Huang, M.; Huang, Y.; Yao, S.; Bassu, P.; Ciais, J.; et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9326–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakery, A.; Vraggalas, S.; Shalha, B.; Chauchan, H.; Benhamed, M.; Fragkostefanakis, S. Heat stress transcription factors as the central molecular rheostat to optimize plant survival and recovery from heat stress. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Takemori, Y.; Sakurai, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Sakurai, H. Differential recognition of heat shock elements by members of the heat shock transcription factor family. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 1962–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poór, P.; Nawaz, K.; Gupta, R.; Ashfaque, F.; Khan, M.I.R. Ethylene involvement in the regulation of heat stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, N.; Takahashi, T.; Komeda, Y. Analysis of tissue-specific expression of Arabidopsis thaliana HSP90-family gene HSP81. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994, 35, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, L.; Cheng, G.; Li, F.; Zhang, S. A pumpkin heat shock factor CmHSF30 positively regulates thermotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2025, 223, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, L.; Zou, M.; Lu, M.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Pei, Y.; Jaworski, K.; Friml, J. TIR1-produced cAMP as a second messenger in transcriptional auxin signalling. Nature 2025, 640, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wang, J.; Chang, M.; Tang, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, T.; et al. TMK-PIN1 drives a short self-organizing circuit for auxin export and signaling in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Pu, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; et al. WAV E3 ubiquitin ligases mediate degradation of IAA32/34 in the TMK1-mediated auxin signaling pathway during apical hook development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2314353121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Kieffer, M.; Yu, H.; Kepinski, S.; Estelle, M. HSP90 regulates temperature-dependent seedling growth in Arabidopsis by stabilizing the auxin co-receptor F-box protein TIR1. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, A.; Mangano, S.; Toribio, R.; Fernández-Calvino, L.; Del Pozo, J.C.; Castellano, M.M. The co-chaperone HOP participates in TIR1 stabilisation and in auxin response in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2508–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, W.M.; Östin, A.; Sandberg, G.; Romano, C.P.; Estelle, M. High temperature promotes auxin-mediated hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7197–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Miao, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, H. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals the involvement of auxin signaling in the heat tolerance of pakchoi under high-temperature stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xie, Q. The sHSP22 heat shock protein requires the ABI1 protein phosphatase to modulate polar auxin transport and downstream responses. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2406–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; He, F.; Kong, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Fan, C.; Luo, K. The IAA17.1/HSFA5a module enhances salt tolerance in Populus tomentosa by regulating flavonol biosynthesis and ROS levels in lateral roots. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranco, R.; Espinosa, J.M.; Prieto-Dapena, P.; Almoguera, C.; Jordano, J. Repression by an auxin/indole acetic acid protein connects auxin signaling with heat shock factor-mediated seed longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21908–21913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, T.; Lin, M.; Kim, J.; Begcy, K.; Liu, Z.; Lee, S. Genome-wide gene network uncover temporal and spatial changes of genes in auxin homeostasis during fruit development in strawberry (F. × ananassa). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Huang, Y.; Qi, P.; Lian, G.; Hu, X.; Han, N.; Wang, J.; Zhu, M.; Qian, Q.; Bian, H. Functional analysis of auxin receptor OsTIR1/OsAFB family members in rice grain yield, tillering, plant height, root system, germination, and auxinic herbicide resistance. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2676–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.K.; Kanno, Y.; Seo, M.; Steber, C.M. Seed dormancy loss from dry after-ripening is associated with increasing gibberellin hormone levels in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1145414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedden, P.; Thomas, S.G. Gibberellin biosynthesis and its regulation. Biochem. J. 2012, 444, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, T.; Davière, J.M.; Achard, P. Long-distance transport of endogenous gibberellins in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1110661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviere, J.M.; Achard, P. Gibberellin signaling in plants. Development 2013, 140, 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colebrook, E.H.; Thomas, S.G.; Phillips, A.L.; Hedden, P. The role of gibberellin signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Gao, X.; Ma, K.; Li, D.; Jia, C.; Zhai, M.; Xu, Z. The walnut transcription factor JrGRAS2 contributes to high temperature stress tolerance involving in Dof transcriptional regulation and HSP protein expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.-Q.; Chen, Y.-X.; Ju, Y.-L.; Pan, C.-Y.; Shan, J.-X.; Ye, W.-W.; Dong, N.-Q.; Kan, Y.; Yang, Y.-B.; Zhao, H.-Y.; et al. Fine-tuning gibberellin improves rice alkali–thermal tolerance and yield. Nature 2025, 639, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, G.; Kim, S.; Thi, T.N.; Kim, H.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, G.; Oh, E. The epidermis coordinates thermoresponsive growth through the phyB-PIF4-auxin pathway. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Bo, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Phytochrome interacting factors PIF4 and PIF5 promote heat stress induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4577–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yao, Y.; Xiang, D.; Du, H.; Geng, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Xie, T.; Dong, F.; Xiong, L. A MITE variation-associated heat-inducible isoform of a heat-shock factor confers heat tolerance through regulation of JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN genes in rice. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1315–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.M.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, T.Q.; Xu, Z.G.; Ma, M.L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.W. The structure of B-ARR reveals the molecular basis of transcriptional activation by cytokinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319335121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ding, B.; Zhu, E.; Deng, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, C.; et al. Phloem unloading via the apoplastic pathway is essential for shoot distribution of root-synthesized cytokinins. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 2111–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, P.D.; Cress, W.A.; Van Staden, J. The involvement of cytokinins in plant responses to environmental stress. Plant Growth Regul. 1997, 23, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortleven, A.; Leuendorf, J.E.; Frank, M.; Pezzetta, D.; Bolt, S.; Schmülling, T. Cytokinin action in response to abiotic and biotic stresses in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 998–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, M.; Jedelský, P.L.; Novák, J.; Schlosser, A.; Brzobohatý, B. Cytokinin modulates proteomic, transcriptomic and growth responses to temperature shocks in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1641–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Xu, Y.; Tian, J.; Gianfagna, T.; Huang, B. Suppression of shade-or heat-induced leaf senescence in creeping bentgrass through transformation with the ipt gene for cytokinin synthesis. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2009, 134, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, B. Cytokinin effects on creeping bentgrass response to heat stress: II. Leaf senescence and antioxidant metabolism. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macková, H.; Hronková, M.; Dobrá, J.; Turečková, V.; Novák, O.; Lubovská, Z.; Motyka, V.; Haisel, D.; Hájek, T.; Prášil, I.T.; et al. Enhanced drought and heat stress tolerance of tobacco plants with ectopically enhanced cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase gene expression. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2805–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prerostova, S.; Rezek, J.; Jarosova, J.; Lacek, J.; Dobrev, P.; Marsik, P.; Gaudinova, A.; Knirsch, V.; Dolezal, K.; Plihalova, L.; et al. Cytokinins act synergistically with heat acclimation to enhance rice thermotolerance affecting hormonal dynamics, gene expression and volatile emission. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2023, 198, 107683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalák, J.; Černý, M.; Jedelský, P.; Dobrá, J.; Ge, E.; Novák, J.; Hronková, M.; Dobrev, P.; Vanková, R.; Brzobohatý, B. Stimulation of ipt overexpression as a tool to elucidate the role of cytokinins in high temperature responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 2861–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilova, M.N.; Kudryakova, N.V.; Doroshenko, A.S.; Zabrodin, D.A.; Vinogradov, N.S.; Kuznetsov, V.V. Molecular and physiological responses of Arabidopsis thaliana plants deficient in the genes responsible for ABA and cytokinin reception and metabolism to heat shock. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 63, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, C.E.; Kieber, J.J. Cytokinin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2002, 14, S47–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunadasa, S.; Kurepa, J.; Smalle, J.A. Gain-of-function of the cytokinin response activator ARR1 increases heat shock tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2073108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, S.; Kerchev, P.; Berka, M.; Černý, M.; Botta, H.K.; Laxmi, A.; Brzobohatý, B. Type-A response regulators negatively mediate heat stress response by altering redox homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 968139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berka, M.; Kopecká, R.; Berková, V.; Brzobohatý, B.; Černý, M. Regulation of heat shock proteins 70 and their role in plant immunity. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1894–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, S.A.; Downs, C.A.; Sharkey, T.D.; Coleman, J.S. The small, methionine-rich chloroplast heat-shock protein protects photosystem II electron transport during heat stress. Plant Physiol. 1998, 116, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Liao, L.; Wei, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, L. Structural basis for abscisic acid efflux mediated by ABCG25 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda-Palazón, B.; Adamo, M.; Valerio, C.; Ferreira, L.J.; Confraria, A.; Reis-Barata, D.; Rodrigues, A.; Meyer, C.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Baena-González, E. A dual function of SnRK2 kinases in the regulation of SnRK1 and plant growth. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkindale, J.; Hall, J.D.; Knight, M.R.; Vierling, E. Heat stress phenotypes of Arabidopsis mutants implicate multiple signaling pathways in the acquisition of thermotolerance. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: From nascent chain to folded protein. Science 2002, 295, 1852–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.K.; Hong, C.B. Over-expression of tobacco NtHSP70-1 contributes to drought-stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Tai, F.; Xue, R.; Li, C. Heat shock protein 70 regulates the abscisic acid-induced antioxidant response of maize to combined drought and heat stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 60, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, S.-S.; Yi, C.-Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J.; Xia, X.-J.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-Q. Hydrogen peroxide mediates abscisic acid-induced HSP70 accumulation and heat tolerance in grafted cucumber plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 2768–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ji, P.; Yang, H.; Jiang, C.; Liang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Lu, F.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. Priming effect of exogenous ABA on heat stress tolerance in rice seedlings is associated with the upregulation of antioxidative defense capability and heat shock-related genes. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 98, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Han, L.; Luo, H. AsHSP17, a creeping bentgrass small heat shock protein modulates plant photosynthesis and ABA-dependent and independent signalling to attenuate plant response to abiotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1320–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Niu, C.-Y.; Yang, C.-R.; Jinn, T.-L. The heat stress factor HSFA6b connects ABA signaling and ABA-mediated heat responses. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotak, S.; Vierling, E.; Bäumlein, H.; von Koskull-Döring, P. A novel transcriptional cascade regulating expression of heat stress proteins during seed development of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-J.; Chen, D.; Mclntyre, C.L.; Dreccer, M.F.; Zhang, Z.-B.; Drenth, J.; Kalaipandian, S.; Chang, H.; Xue, G.-P. Heat shock factor C2a serves as a proactive mechanism for heat protection in developing grains in wheat via an ABA-mediated regulatory pathway. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhuang, L.; Shi, Y.; Huang, B. Up-regulation of HSFA2c and HSPs by ABA contributing to improved heat tolerance in tall fescue and Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Li, C.; Chen, N.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. The calcium-dependent protein kinase ZmCDPK7 functions in heat-stress tolerance in maize. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, F.; Li, Z.; Waadt, R.; Schroeder, J.I. SnapShot: Abscisic acid signaling. Cell 2017, 171, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Kong, X.; Yu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, Y. Responses of PYR/PYL/RCAR ABA receptors to contrasting stresses, heat and cold in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 14, 1670596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Liu, A.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Gao, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X. Expression analysis of nine rice heat shock protein genes under abiotic stresses and ABA treatment. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgakov, V.P.; Wu, H.-C.; Jinn, T.-L. Coordination of ABA and chaperone signaling in plant stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, M.; Leonhardt, N.; Droillard, M.-J.; Reiter, I.; Montillet, J.-L.; Genty, B.; Laurière, C.; Nussaume, L.; Noël, L.D. The cytosolic/nuclear HSC70 and HSP90 molecular chaperones are important for stomatal closure and modulate abscisic acid-dependent physiological responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.W.; Mandava, N.; Worley, J.F.; Plimmer, J.R.; Smith, M.V. Brassins—A new family of plant hormones from rape pollen. Nature 1970, 225, 1065–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajguz, A. Metabolism of brassinosteroids in plants. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2007, 45, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-Y.; Bai, M.-Y.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3767–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xue, H.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Long, H.; Zhao, J.; Meng, F.; Liu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Luo, X.; et al. ERF49 mediates brassinosteroid regulation of heat stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, F.; Jahan, B.; Kumari, S.; Iqbal, N.; Albaqami, M.; Sofo, A.; Khan, M.I.R. Brassinosteroid modulates ethylene synthesis and antioxidant metabolism to protect rice (Oryza sativa) against heat stress-induced inhibition of source-sink capacity and photosynthetic and growth attributes. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 289, 154096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kour, J.; Kohli, S.K.; Khanna, K.; Bskshi, P.; Sharma, P.; Singh, A.D.; Ibrahim, M.; Devi, K.; Sharma, N.; Ohri, P.; et al. Brassinosteroid signaling, crosstalk and, physiological functions in plants under heavy metal stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 608061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Sae-Seaw, J.; Wang, Z.-Y. Brassinosteroid signalling. Development 2013, 140, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wu, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, D.; Gao, K.; Tang, W. Heat shock-induced accumulation of the glycogen synthase kinase 3-like kinase brassinosteroid insensitive 2 promotes early flowering but reduces thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 838062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, C.; Espinosa-Ruíz, A.; de Lucas, M.; Bernardo-García, S.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; Prat, S. PIF4-induced BR synthesis is critical to diurnal and thermomorphogenic growth. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaubhadel, S.; Chaudhary, S.; Dobinson, K.F.; Krishna, P. Treatment with 24-epibrassinolide, a brassinosteroid, increases the basic thermotolerance of Brassica napus and tomato seedlings. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 40, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Jiang, J.; Sun, S.; Wang, X. Brassinosteroids promote thermotolerance through releasing BIN2-mediated phosphorylation and suppression of HsfA1 transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, M.A.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, C.; Kamran, H.M.; Altaf, M.A.; Hao, Y.; Shu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Abbas, H.M.K.; et al. Interaction between transcriptional activator BRI1-EMS-SUPPRESSOR 1 and HSPs regulates heat stress tolerance in pepper. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 211, 105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Bao, X.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, X. The leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase protein TaSERK1 positively regulates high-temperature seedling plant resistance to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici by interacting with TaDJA7. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Wang, Z.-Y. Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavaliev, R.; Dong, X. NPR1, a key immune regulator for plant survival under biotic and abiotic stresses. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancheya, T.V.; Popoya, L.P.; Uzunoya, A.N. Effects of salicylic acid on growth and photosynthesis in barley plants. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 149, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Manna, M.; Kaur, H.; Thakur, T.; Gandass, N.; Bhatt, D.; Muthamilarasan, M. Phytohormone signaling and crosstalk in regulating drought stress response in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1305–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Z.L.; Hanzlik, S.; Cook, E.; Shen, Q.J. Salicylic acid inhibits gibberellin-induced alpha-amylase expression and seed germination via a pathway involving an abscisic-acid-inducible WRKY gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 64, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefevere, H.; Bauters, L.; Gheysen, G. Salicylic acid biosynthesis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Ortega, M.A.; Tsai, C.J. The diversity of salicylic acid biosynthesis and defense signaling in plants: Knowledge gaps and future opportunities. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2023, 72, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, E.; Szalai, G.; Janda, T. Induction of abiotic stress tolerance by salicylic acid signaling. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 26, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhan, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Wen, P.; Huang, W. Salicylic acid synthesized by benzoic acid 2-hydroxylase participates in the development of thermotolerance in pea plants. Plant Sci. 2006, 171, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Qu, L.; Hu, Y.; Lu, D. Transcriptomic and alternative splicing analyses provide insights into the roles of exogenous salicylic acid ameliorating waxy maize seedling growth under heat stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-J.; Fan, L.; Loescher, W.; Duan, W.; Liu, G.-J.; Cheng, J.-S.; Luo, H.-B.; Li, S.-H. Salicylic acid alleviates decreases in photosynthesis under heat stress and accelerates recovery in grapevine leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Dai, S.; Zhang, M.; Meng, Q.; Ma, N.; Zhuang, K. Salicylic acid regulates two photosystem II protection pathways in tomato under chilling stress mediated by ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 3-like proteins. Plant J. 2023, 114, 1385–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, S.; Sheteiwy, M.S.A.; Zhang, H.; Shao, H.; Guo, X. TaHsfA2-1, a new gene for thermotolerance in wheat seedlings: Characterization and functional roles. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 246, 153135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, M.; Cronjé, M.J. Modulation of heat shock factors accompanies salicylic acid-mediated potentiation of Hsp70 in tomato seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronjé, M.J.; Weir, I.E.; Bornman, L. Salicylic acid-mediated potentiation of Hsp70 induction correlates with reduced apoptosis in tobacco protoplasts. Cytom. Part A 2004, 61, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Goswami, S.; Verma, P.; Singh, K.; Dixit, N.; Pathak, H.; Viswanathan, C.; Rai, R.D. Salicylic acid alleviates the heat stress-induced oxidative damage of starch biosynthesis pathway by modulating the expression of heat-stable genes and proteins in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Acta Physiol. Plant 2015, 37, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.; Feng, B.H.; Chen, T.T.; Zhang, X.F.; Tao, L.X.; Fu, G.F. Sugars, antioxidant enzymes and IAA mediate salicylic acid to prevent rice spikelet degeneration caused by heat stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 83, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, P.; Ecker, J.R. Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, H.; Abreu, I.; López Ortiz, J.; Peralta Ogorek, L.L.; Shukla, V.; Mäkelä, M.; Lyu, M.; Shapiguzov, A.; Licausi, F.; Mähönen, A.P. Plants monitor the integrity of their barrier by sensing gas diffusion. Nature 2025, 644, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Bürger, M.; Chory, J.; Wang, X. The role of ethylene in plant temperature stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslop-Harrison, G.; Nakabayashi, K.; Espinosa-Ruiz, A.; Robertson, F.; Baines, R.; Thompson, C.R.L.; Hermann, K.; Alabadí, D.; Leubner-Metzger, G.; Williams, R.S.B. Functional mechanism study of the allelochemical myrigalone A identifies a group of ultrapotent inhibitors of ethylene biosynthesis in plants. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, Q.; Rothenberg, M.; Solano, R.; Roman, G.; Terzaghi, W.; Ecker, J.R. Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell 1997, 89, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, D.B.; Do, J.H.; Mason, R.E.; Morgan, G.; Finlayson, S.A. Heat stress induced ethylene production in developing wheat grains induces kernel abortion and increased maturation in a susceptible cultivar. Plant Sci. 2007, 172, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Bürger, M.; Wang, Y.; Chory, J. Two interacting ethylene response factors regulate heat stress response. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, Z.; Liu, X.; Sun, D.; Tang, W. Transcriptional profiling reveals a time-of-day-specific role of REVEILLE 4/8 in regulating the first wave of heat shock-induced gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2353–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-C.; Liao, P.-M.; Kuo, W.-W.; Lin, T.-P. The Arabidopsis ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 regulates abiotic stress-responsive gene expression by binding to different cis-acting elements in response to different stress signals. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1566–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Q.; Fan, F.; Fu, R.; Ahammed, G.J.; Yu, J.; Shi, K. Role of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling in elevated CO2-induced heat stress response in tomato. Planta 2019, 250, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-S.; Yang, C.-Y. Ethylene-mediated signaling confers thermotolerance and regulates transcript levels of heat shock factors in rice seedlings under heat stress. Bot. Stud. 2019, 60, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.E.; Whichard, L.P.; Turner, B.; Wall, M.E.; Egley, G.H. Germination of witchweed (Striga lutea Lour.): Isolation and properties of a potent stimulant. Science 1966, 154, 1189–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Kane, A.; Wu, S.; Wang, K.; Santiago, M.; Ishiguro, Y.; Yoneyama, K.; Palayam, M.; Shabek, N.; Xie, X.; et al. Evolution of interorganismal strigolactone biosynthesis in seed plants. Science 2025, 387, eadp0779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dong, L.; Durairaj, J.; Guan, J.C.; Yoshimura, M.; Quinodoz, P.; Horber, R.; Gaus, K.; Li, J.; Setotaw, Y.B.; et al. Maize resistance to witchweed through changes in strigolactone biosynthesis. Science 2023, 379, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, E.; Chai, L.; Zhang, S.; Yu, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Hu, Y. Catabolism of strigolactones by a carboxylesterase. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; He, Y.; Hao, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Ban, X.; et al. Regulatory mechanisms of strigolactone perception in rice. Cell 2024, 187, 7551–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Roldan, V.; Fermas, S.; Brewer, P.B.; Puech-Pagès, V.; Dun, E.A.; Pillot, J.P.; Letisse, F.; Matusova, R.; Danoun, S.; Portais, J.-C.; et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature 2008, 455, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umehara, M.; Hanada, A.; Yoshida, S.; Akiyama, K.; Arite, T.; Takeda-Kamiya, N.; Magome, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Yoneyama, K.; et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature 2008, 455, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, M.G.; Li, W.; Nguyen, K.H.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.-S.P. Strigolactones in plant adaptation to abiotic stresses: An emerging avenue of plant research. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 2227–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.; Kamiya, Y.; Kawakami, N.; Nambara, E.; McCourt, P.; Tsuchiya, Y. Thermoinhibition uncovers a role for strigolactones in Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Fang, P.; Zhou, J.; Xia, X.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J. Strigolactones positively regulate abscisic acid-dependent heat and cold tolerance in tomato. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, J.; Zhu, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chu, S.; Xiong, E.; Zheng, X.; Jiao, Y. AtMYBS1 negatively regulates heat tolerance by directly repressing the expression of MAX1 required for strigolactone biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, W.; Cheng, X.; Lin, D.; He, C.; Shi, H. Heat shock protein 90 co-chaperone modules fine-tune the antagonistic interaction between salicylic acid and auxin biosynthesis in cassava. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plitsi, P.K.; Samakovli, D.; Roka, L.; Rampou, A.; Panagiotopoulos, K.; Koudounas, K.; Isaioglou, I.; Haralampidis, K.; Rigas, S.; Hatzopoulos, P.; et al. GA-mediated disruption of RGA/BZR1 complex requires HSP90 to promote hypocotyl elongation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lämke, J.; Brzezinka, K.; Altmann, S.; Bäurle, I. A hit-and-run heat shock factor governs sustained histone methylation and transcriptional stress memory. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Matsubara, S.; Yoshimizu, K.; Seki, M.; Hamada, K.; Kamitani, M.; Kurita, Y.; Nomura, Y.; Nagashima, K.; Inagaki, S.; et al. H3K27me3 demethylases alter HSP22 and HSP17.6C expression in response to recurring heat in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.R.; Pathak, H.; Sharma, S.K.; Kale, Y.K.; Nirjal, M.K.; Singh, G.P.; Goswami, S.; Rai, R.D. Novel and conserved heat-responsive microRNAs in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Funct. Integr. Genom. 2014, 15, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, F.; Zou, X.; Lan, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Zhou, F.; Yin, C.; Lin, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of the Phytohormone–Heat Shock Protein Pathway in Regulating Plant Thermotolerance. Plants 2025, 14, 3706. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233706

Zhang J, Zhu Y, Ma F, Zou X, Lan Q, Zhou X, Li M, Zhou F, Yin C, Lin Y. Molecular Mechanisms of the Phytohormone–Heat Shock Protein Pathway in Regulating Plant Thermotolerance. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3706. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233706

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jialiang, Yanchun Zhu, Fumin Ma, Xiao Zou, Qiuxia Lan, Xiaoran Zhou, Mengxia Li, Fei Zhou, Changxi Yin, and Yongjun Lin. 2025. "Molecular Mechanisms of the Phytohormone–Heat Shock Protein Pathway in Regulating Plant Thermotolerance" Plants 14, no. 23: 3706. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233706

APA StyleZhang, J., Zhu, Y., Ma, F., Zou, X., Lan, Q., Zhou, X., Li, M., Zhou, F., Yin, C., & Lin, Y. (2025). Molecular Mechanisms of the Phytohormone–Heat Shock Protein Pathway in Regulating Plant Thermotolerance. Plants, 14(23), 3706. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233706