The Mid-Domain Effect Shapes a Unimodal Latitudinal Pattern in Fruiting Phenology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

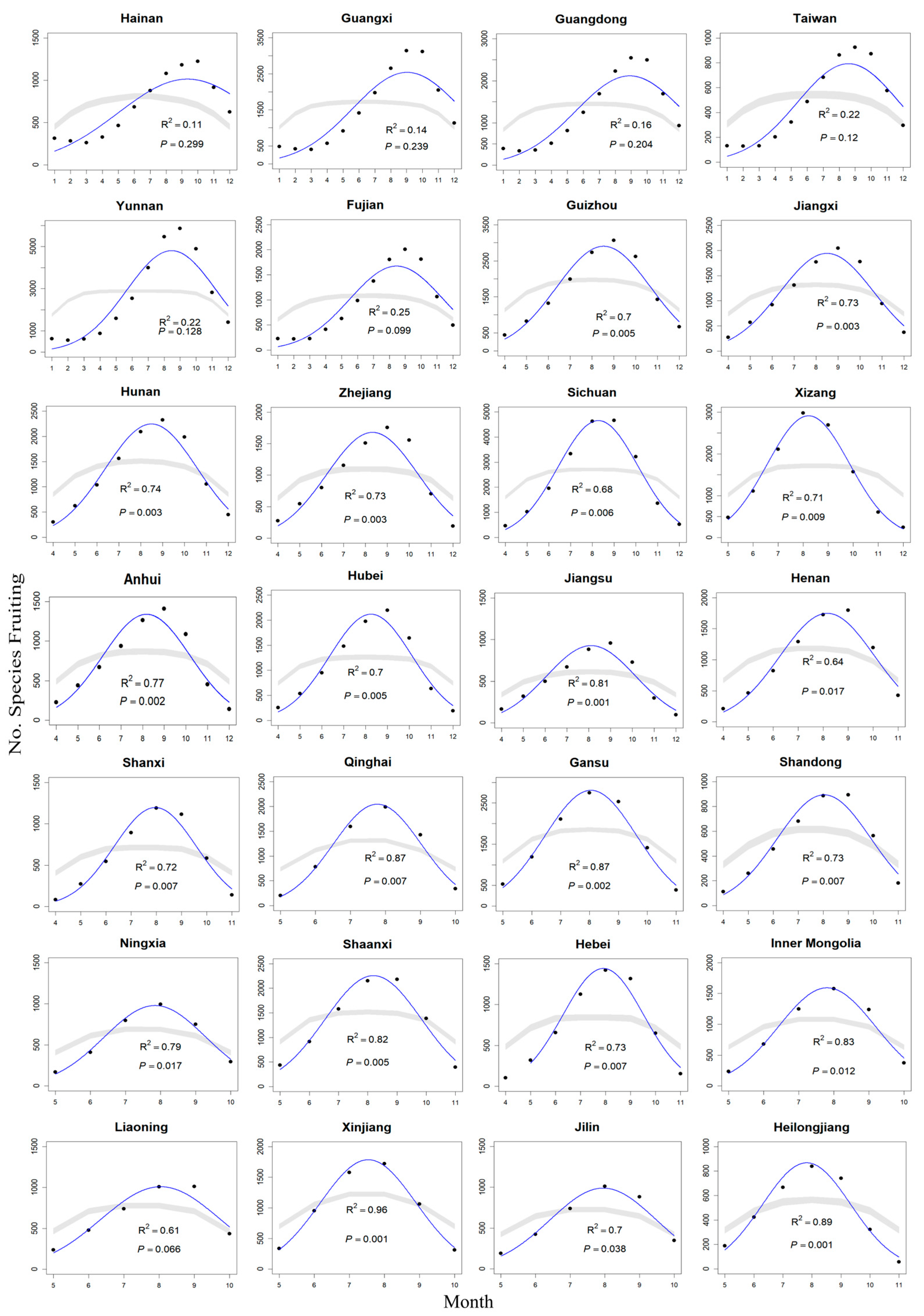

2.1. Mid-Domain Effect in Peak Fruiting Phenology

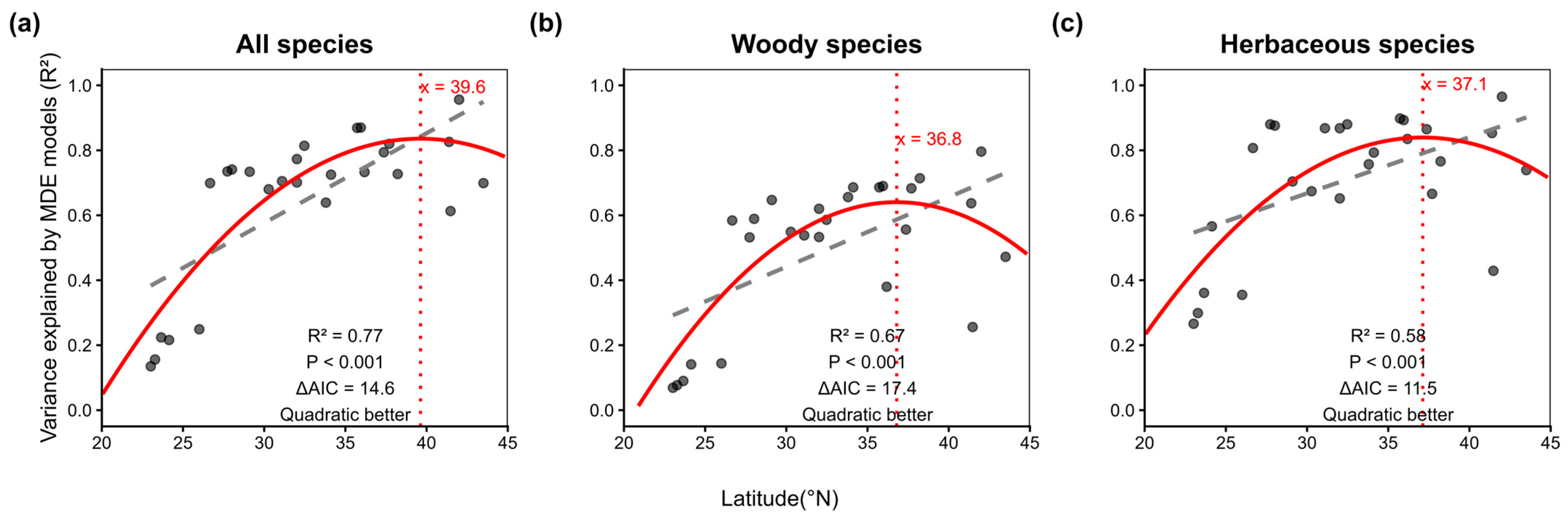

2.2. Latitudinal Patterns of the Mid-Domain Effect

2.3. Relationship Between Climatic Variables and Fruiting Diversity

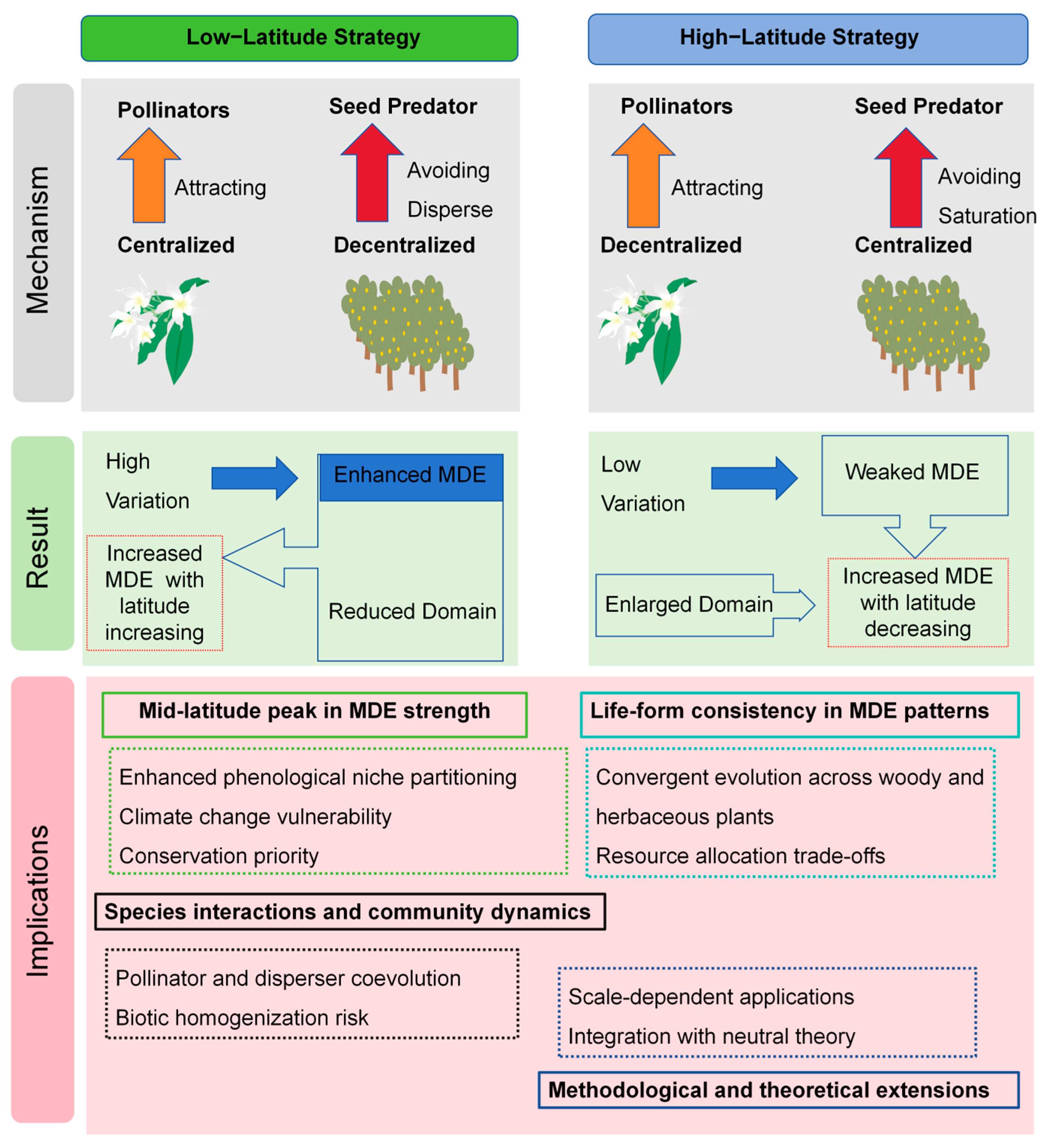

3. Discussion

3.1. Interpretation of the Mid-Domain Effect in Peak Fruiting Phenology

3.2. The Mid-Domain Effect as a Driver of Fruiting Diversity

3.3. Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Species Distribution and Phenology Data

4.2. Climatic Data

4.3. Data Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDE | Mid-domain effect |

References

- Albert-Daviaud, A.; Buerki, S.; Onjalalaina, G.E.; Perillo, S.; Rabarijaona, R.; Razafindratsima, O.H.; Sato, H.; Valenta, K.; Wright, P.C.; Stuppy, W. The Ghost Fruits of Madagascar: Identifying Dysfunctional Seed Dispersal in Madagascar’s Endemic Flora. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascompte, J.; Jordano, P.; Olesen, J.M. Asymmetric Coevolutionary Networks Facilitate Biodiversity Maintenance. Science 2006, 312, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Momose, K.; Yumoto, T.; Nagamitsu, T.; Nagamasu, H.; Hamid, A.A.; Nakashizuka, T. Plant Reproductive Phenology over Four Years Including an Episode of General Flowering in a Lowland Dipterocarp Forest, Sarawak, Malaysia. Am. J. Bot. 1999, 86, 1414–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalling, J.W.; Davis, A.S.; Schutte, B.J.; Arnold, A.E. Seed Survival in Soil: Interacting Effects of Predation, Dormancy and the Soil Microbial Community. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Robles, M.; Andresen, E.; Díaz-Castelazo, C. Temporal Changes in the Structure of a Plant-Frugivore Network Are Influenced by Bird Migration and Fruit Availability. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, S.E.; Augspurger, C.K. Aggregated Seed Dispersal by Spider Monkeys Limits Recruitment to Clumped Patterns in Virola calophylla. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araye, Q.; Yahara, T.; Satake, A. Latitudinal Cline of Flowering and Fruiting Phenology in Fagaceae in Asia. Biotropica 2023, 55, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Flores, J.; Cornejo-Tenorio, G.; Urrea-Galeano, L.A.; Andresen, E.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Ibarra-Manríquez, G. Phylogeny, Fruit Traits, and Ecological Correlates of Fruiting Phenology in a Neotropical Dry Forest. Oecologia 2019, 189, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkovich, E.M.; Cook, B.I.; Allen, J.M.; Crimmins, T.M.; Betancourt, J.L.; Travers, S.E.; Pau, S.; Regetz, J.; Davies, T.J.; Kraft, N.J.B.; et al. Warming Experiments Underpredict Plant Phenological Responses to Climate Change. Nature 2012, 485, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K.; Hurtt, G.C. Nonbiological Gradients in Species Richness and a Spurious Rapoport Effect. Am. Nat. 1994, 144, 570–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Li, Q.; Onditi, K.; Khanal, L.; Jiang, X. Small Mammal Species Richness and Turnover along Elevational Gradient in Yulong Mountain, Yunnan, Southwest China. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chettri, B.; Acharya, B.K. Distribution of Amphibians along an Elevation Gradient in the Eastern Himalaya, India. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2020, 47, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K.; Rahbek, C.; Gotelli, N.J. The Mid-Domain Effect and Species Richness Patterns:What Have We Learned So Far? Am. Nat. 2004, 163, E1–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, C.C.; Vrcibradic, D.; Almeida-Gomes, M.; Rocha, C.F.D. Assessing the Importance of Reproductive Modes for the Evaluation of Altitudinal Distribution Patterns in Tropical Frogs. Biotropica 2021, 53, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.A.; Dodge, G.J.; Inouye, D.W. A Phenological Mid-Domain Effect in Flowering Diversity. Oecologia 2005, 142, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, R.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Mao, L.; Chen, G.; Lai, J.; Ma, K. The Mid-Domain Effect in Flowering Phenology. Plant Divers. 2024, 46, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, D.W. Effects of Climate Change on Phenology, Frost Damage, and Floral Abundance of Montane Wildflowers. Ecology 2008, 89, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.S. Beyond Neutral Science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, S.P. Neutral Theory in Community Ecology and the Hypothesis of Functional Equivalence. Funct. Ecol. 2005, 19, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, T.F.L.V.B.; Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. Neutral Community Dynamics, the Mid-domain Effect and Spatial Patterns in Species Richness. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosindell, J.; Hubbell, S.P.; Etienne, R.S. The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography at Age Ten. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdziewicz, M.; Szymkowiak, J.; Tanentzap, A.J.; Calama, R.; Marino, S.; Steele, M.A.; Seget, B.; Piechnik, Ł.; Żywiec, M. Seed Predation Selects for Reproductive Variability and Synchrony in Perennial Plants. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, A.L.; Ensing, J.; Rahn, O.; Oliveira, F.M.P.; Burkiewicz, J.; Lafond, J.; Haeussler, S.; Byerley-Best, M.B.; Lazda, K.; Slinn, H.L.; et al. Latitudinal Gradients in Seed Predation Persist in Urbanized Environments. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colwell, R.K.; Gotelli, N.; Rahbek, C.; Entsminger, G.; Farrell, C.; Graves, G. Peaks, Plateaus, Canyons, and Craters: The Complex Geometry of Simple Mid-Domain Effect Models. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2009, 11, 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, R.K.; Lees, D.C. The Mid-Domain Effect: Geometric Constraints on the Geography of Species Richness. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000, 15, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponsler, D.; Iverson, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. Pollinator Competition and the Structure of Floral Resources. Ecography 2023, 2023, e06651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, D.A.; Kelly, D. Mast Seeding Over 33 Years by Dacrydium Cupressinum Lamb. (Rimu) (Podocarpaceae) in New Zealand: The Importance of Economies of Scale. Funct. Ecol. 1988, 2, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jian, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Ciais, P.; Zscheischler, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Müller, C.; Webber, H.; et al. Extreme Rainfall Reduces One-Twelfth of China’s Rice Yield over the Last Two Decades. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zohner, C.M.; Peñuelas, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Shen, P.; Jia, X.; et al. Declining Precipitation Frequency May Drive Earlier Leaf Senescence by Intensifying Drought Stress and Enhancing Drought Acclimation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, R. Soil and Stem Water Storage Determine Phenology and Distribution of Tropical Dry Forest Trees. Ecology 1994, 75, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J.K.; Wright, S.J.; Calderón, O.; Pagan, M.A.; Paton, S. Flowering and Fruiting Phenologies of Seasonal and Aseasonal Neotropical Forests: The Role of Annual Changes in Irradiance. J. Trop. Ecol. 2007, 23, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauset, S.; Freitas, H.C.; Galbraith, D.R.; Sullivan, M.J.P.; Aidar, M.P.M.; Joly, C.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Vieira, S.A.; Gloor, M.U. Differences in Leaf Thermoregulation and Water Use Strategies between Three Co-occurring Atlantic Forest Tree Species. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1618–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.-W.; Leigh, A.; Guo, J.-J.; Fang, L.-D.; Hao, G.-Y. Sand Dune Shrub Species Prioritize Hydraulic Integrity over Transpirational Cooling during an Experimental Heatwave. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 336, 109483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, K.; Nippert, J.B. Drivers of Nocturnal Water Flux in a Tallgrass Prairie. Funct. Ecol. 2018, 32, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Maroco, J.P.; Pereira, J.S. Understanding Plant Responses to Drought—From Genes to the Whole Plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.J.; Leuzinger, S.; Philipson, C.D.; Tay, J.; Hector, A. Drought Survival of Tropical Tree Seedlings Enhanced by Non-Structural Carbohydrate Levels. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, D.; Rapp, J.K.; Sork, V.L.; Rathcke, B.J.; Reese, G.A.; Weaver, J.C. Phenological Properties of Wind- and Insect-Pollinated Prairie Plants. Ecology 1981, 62, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.D. Climatic and Phylogenetic Determinants of Flowering Seasonality in the Cape Flora. J. Ecol. 1993, 81, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochmer, J.P.; Handel, S.N. Constraints and Competition in the Evolution of Flowering Phenology. Ecol. Monogr. 1986, 56, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.J.; Calderon, O. Phylogenetic Patterns among Tropical Flowering Phenologies. J. Ecol. 1995, 83, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Mao, L.; Queenborough, S.A.; Primack, R.; Comita, L.S.; Hampe, A.; Ma, K. Macro-scale Variation and Environmental Predictors of Flowering and Fruiting Phenology in the Chinese Angiosperm Flora. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 2303–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, B.H.; Bakker, F.T.; Bellstedt, D.U.; Bytebier, B.; Claßen-Bockhoff, R.; Dreyer, L.L.; Edwards, D.; Forest, F.; Galley, C.; Hardy, C.R.; et al. Consistent Phenological Shifts in the Making of a Biodiversity Hotspot: The Cape Flora. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, J.; Willis, C.G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, T.; Dai, W.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, K. Phylogenetic Conservatism and Trait Correlates of Spring Phenological Responses to Climate Change in Northeast China. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 6747–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Fu, Y.H.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, X.; Piao, S. Temperature, Precipitation, and Insolation Effects on Autumn Vegetation Phenology in Temperate China. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, E.; Chuine, I.; Menzel, A.; Mooney, H.; Schwartz, M. Shifting Plant Phenology in Response to Global Change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Fu, Y.H.; Du, Y.; Huang, Z. Global Warming Increases Latitudinal Divergence in Flowering Dates of a Perennial Herb in Humid Regions across Eastern Asia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 296, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, A. rangemodelR: Mid-Domain Effect and Species Richness, version 1.0.6; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A Review of Methods to Deal with It and a Simulation Study Evaluating Their Performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Mao, L. Glmm.Hp: An R Package for Computing Individual Effect of Predictors in Generalized Linear Mixed Models. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Zhu, W.; Cui, D.; Mao, L. Extension of the Glmm.Hp Package to Zero-Inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Models and Multiple Regression. J. Plant Ecol. 2023, 16, rtad038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Province | Latitude | All Species | Herbaceous Species | Woody Species | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | R2 | p | Period | F | R2 | p | Period | F | R2 | p | Period | ||

| Hainan | 19.222 | 1.2 | 0.107 | 0.299 | 1–12 | 3.3 | 0.250 | 0.098 | 1–12 | 0.3 | 0.033 | 0.573 | 1–12 |

| Guangxi | 23.015 | 1.6 | 0.135 | 0.239 | 1–12 | 3.6 | 0.266 | 0.086 | 1–12 | 0.7 | 0.069 | 0.408 | 1–12 |

| Guangdong | 23.277 | 1.8 | 0.156 | 0.204 | 1–12 | 4.3 | 0.299 | 0.066 | 1–12 | 0.8 | 0.077 | 0.382 | 1–12 |

| Taiwan | 23.657 | 2.9 | 0.224 | 0.120 | 1–12 | 5.7 | 0.361 | 0.039 | 1–12 | 1.0 | 0.090 | 0.345 | 1–12 |

| Yunnan | 24.141 | 2.7 | 0.216 | 0.128 | 1–12 | 10.5 | 0.566 | 0.012 | 3–12 | 1.6 | 0.141 | 0.230 | 1–12 |

| Fujian | 26.004 | 3.3 | 0.249 | 0.099 | 1–12 | 5.5 | 0.355 | 0.041 | 1–12 | 1.7 | 0.144 | 0.224 | 1–12 |

| Guizhou | 26.668 | 16.2 | 0.699 | 0.005 | 4–12 | 29.4 | 0.807 | <0.001 | 4–12 | 9.8 | 0.584 | 0.016 | 4–12 |

| Jiangxi | 27.735 | 19.4 | 0.735 | 0.003 | 4–12 | 51.4 | 0.880 | <0.001 | 4–12 | 7.9 | 0.532 | 0.026 | 4–12 |

| Hunan | 28.016 | 20.0 | 0.741 | 0.003 | 4–12 | 49.6 | 0.876 | <0.001 | 4–12 | 10.0 | 0.589 | 0.016 | 4–12 |

| Zhejiang | 29.105 | 19.3 | 0.734 | 0.003 | 4–12 | 14.3 | 0.704 | 0.009 | 4–11 | 11.0 | 0.647 | 0.016 | 4–12 |

| Sichuan | 30.277 | 14.9 | 0.680 | 0.006 | 4–12 | 12.4 | 0.674 | 0.012 | 4–11 | 8.5 | 0.549 | 0.022 | 4–12 |

| Xizang | 31.101 | 14.3 | 0.705 | 0.009 | 5–12 | 32.9 | 0.868 | 0.002 | 5–11 | 8.2 | 0.538 | 0.024 | 4–12 |

| Anhui | 32.014 | 23.8 | 0.773 | 0.002 | 4–12 | 45.9 | 0.868 | <0.001 | 4–12 | 8.0 | 0.533 | 0.025 | 4–12 |

| Hubei | 32.014 | 16.4 | 0.701 | 0.005 | 4–12 | 11.2 | 0.652 | 0.015 | 4–11 | 11.4 | 0.620 | 0.012 | 4–12 |

| Jiangsu | 32.472 | 30.6 | 0.814 | <0.001 | 4–12 | 51.2 | 0.880 | <0.001 | 4–12 | 9.9 | 0.586 | 0.016 | 4–12 |

| Henan | 33.8 | 10.6 | 0.639 | 0.017 | 4–11 | 18.7 | 0.757 | 0.005 | 4–11 | 9.5 | 0.656 | 0.027 | 5–11 |

| Shanxi | 34.115 | 15.8 | 0.725 | 0.007 | 4–11 | 23.0 | 0.793 | 0.003 | 4–11 | 10.9 | 0.686 | 0.021 | 5–11 |

| Qinghai | 35.723 | 26.6 | 0.869 | 0.007 | 5–10 | 35.3 | 0.898 | 0.004 | 5–10 | 8.7 | 0.686 | 0.042 | 5–10 |

| Gansu | 35.949 | 33.4 | 0.870 | 0.002 | 5–11 | 41.7 | 0.893 | 0.001 | 5–11 | 11.1 | 0.690 | 0.021 | 5–11 |

| Shandong | 36.178 | 16.5 | 0.733 | 0.007 | 4–11 | 30.3 | 0.835 | 0.002 | 4–11 | 3.7 | 0.380 | 0.103 | 4–11 |

| Ningxia | 37.366 | 15.4 | 0.794 | 0.017 | 5–10 | 25.6 | 0.865 | 0.007 | 5–10 | 5.0 | 0.556 | 0.089 | 5–10 |

| Shaanxi | 37.699 | 22.7 | 0.820 | 0.005 | 5–11 | 12.0 | 0.666 | 0.013 | 4–11 | 10.8 | 0.683 | 0.022 | 5–11 |

| Hebei | 38.222 | 16.0 | 0.727 | 0.007 | 4–11 | 19.7 | 0.766 | 0.004 | 4–11 | 12.5 | 0.714 | 0.017 | 5–11 |

| Inner Mongolia | 41.386 | 19.0 | 0.826 | 0.012 | 5–10 | 23.2 | 0.853 | 0.009 | 5–10 | 7.0 | 0.637 | 0.057 | 5–10 |

| Liaoning | 41.474 | 6.3 | 0.613 | 0.066 | 5–10 | 3.8 | 0.429 | 0.110 | 4–10 | 1.4 | 0.256 | 0.306 | 5–10 |

| Xinjiang | 42.002 | 87.0 | 0.956 | <0.001 | 5–10 | 111.5 | 0.965 | <0.001 | 5–10 | 15.6 | 0.796 | 0.017 | 5–10 |

| Jilin | 43.501 | 9.3 | 0.699 | 0.038 | 5–10 | 11.4 | 0.739 | 0.028 | 5–10 | 3.6 | 0.472 | 0.132 | 5–10 |

| Heilongjiang | 46.77 | 39.8 | 0.888 | 0.001 | 5–11 | 20.9 | 0.777 | 0.004 | 5–11 | 3.3 | 0.453 | 0.143 | 5–10 |

| All Species | Herbaceous Species | Woody Species | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | p | I.perc (%) | t | p | I.perc (%) | t | p | I.perc (%) | |

| mid-domain effect | 21.4 | <0.001 | 89.18 | 26.3 | <0.001 | 92.96 | 23.0 | <0.001 | 72.85 |

| Tmin | 3.0 | 0.002 | 6.43 | 3.6 | <0.001 | 4.41 | 5.0 | <0.001 | 15.50 |

| MMP | −1.2 | 0.234 | 2.73 | −0.8 | 0.423 | 1.20 | −2.5 | 0.012 | 6.71 |

| sunshine | −0.9 | 0.350 | 1.67 | −1.9 | 0.059 | 1.44 | 0.24 | 0.811 | 4.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Xue, Q.; Du, Y. The Mid-Domain Effect Shapes a Unimodal Latitudinal Pattern in Fruiting Phenology. Plants 2025, 14, 3701. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233701

Zhang L, Xue Q, Du Y. The Mid-Domain Effect Shapes a Unimodal Latitudinal Pattern in Fruiting Phenology. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3701. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233701

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Longyang, Qianhuai Xue, and Yanjun Du. 2025. "The Mid-Domain Effect Shapes a Unimodal Latitudinal Pattern in Fruiting Phenology" Plants 14, no. 23: 3701. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233701

APA StyleZhang, L., Xue, Q., & Du, Y. (2025). The Mid-Domain Effect Shapes a Unimodal Latitudinal Pattern in Fruiting Phenology. Plants, 14(23), 3701. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233701