Nitrogen Topdressing Rate Alters Starch and Protein Properties in Grains at Different Spike Positions Under Long-Term Field Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

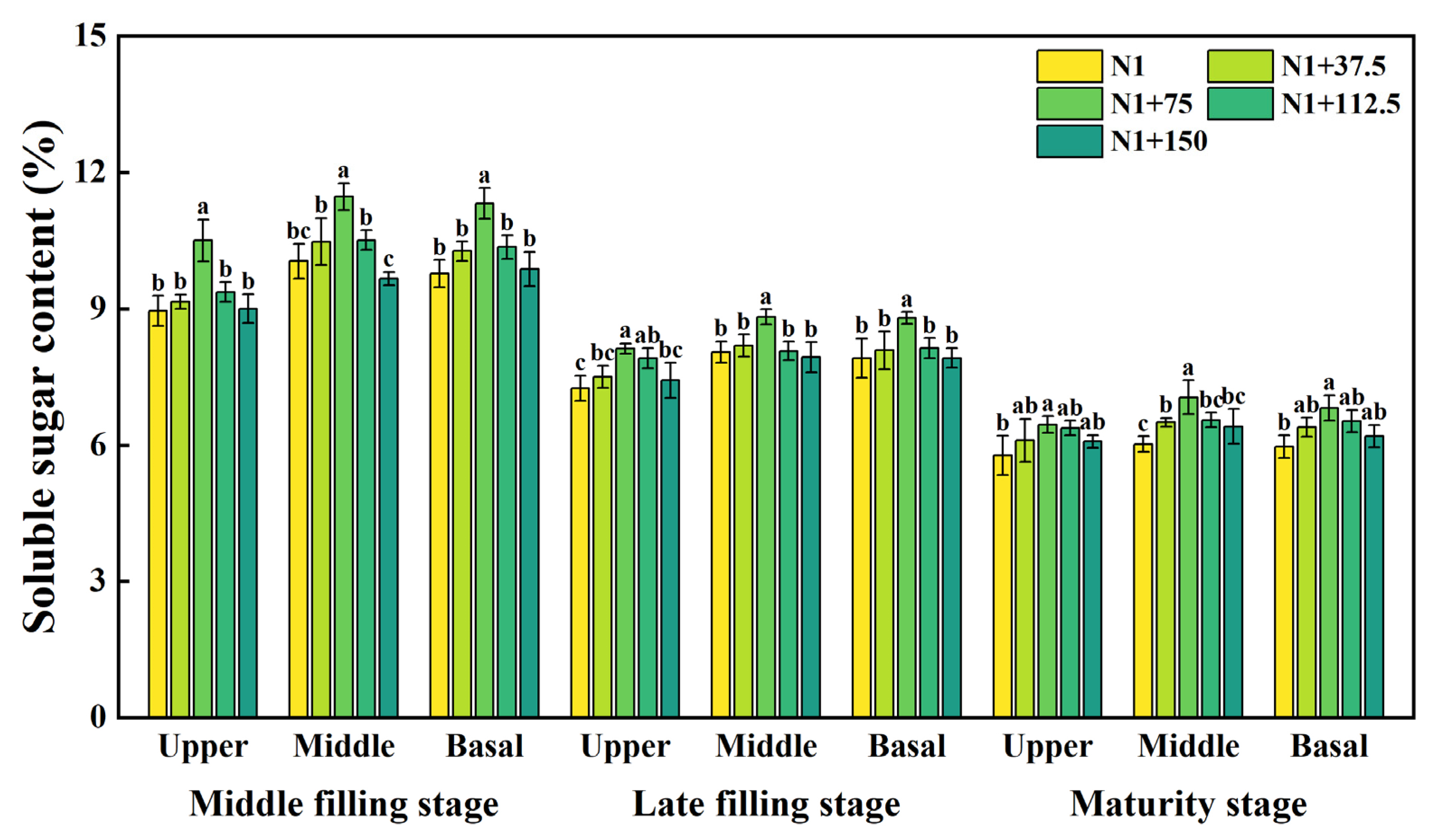

2.1. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on Soluble Sugar Content in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

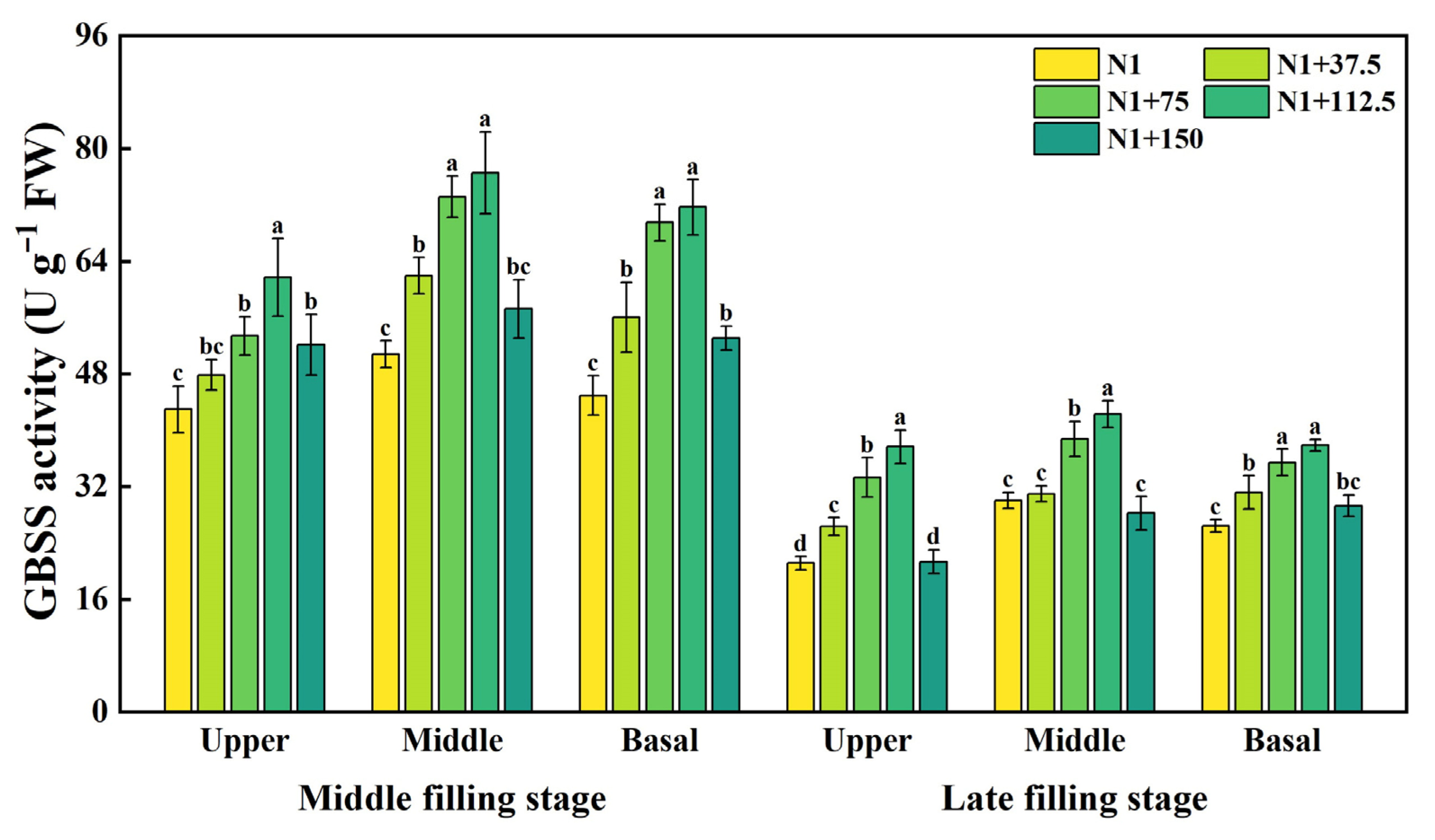

2.2. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the Enzyme Activity of GBSS in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

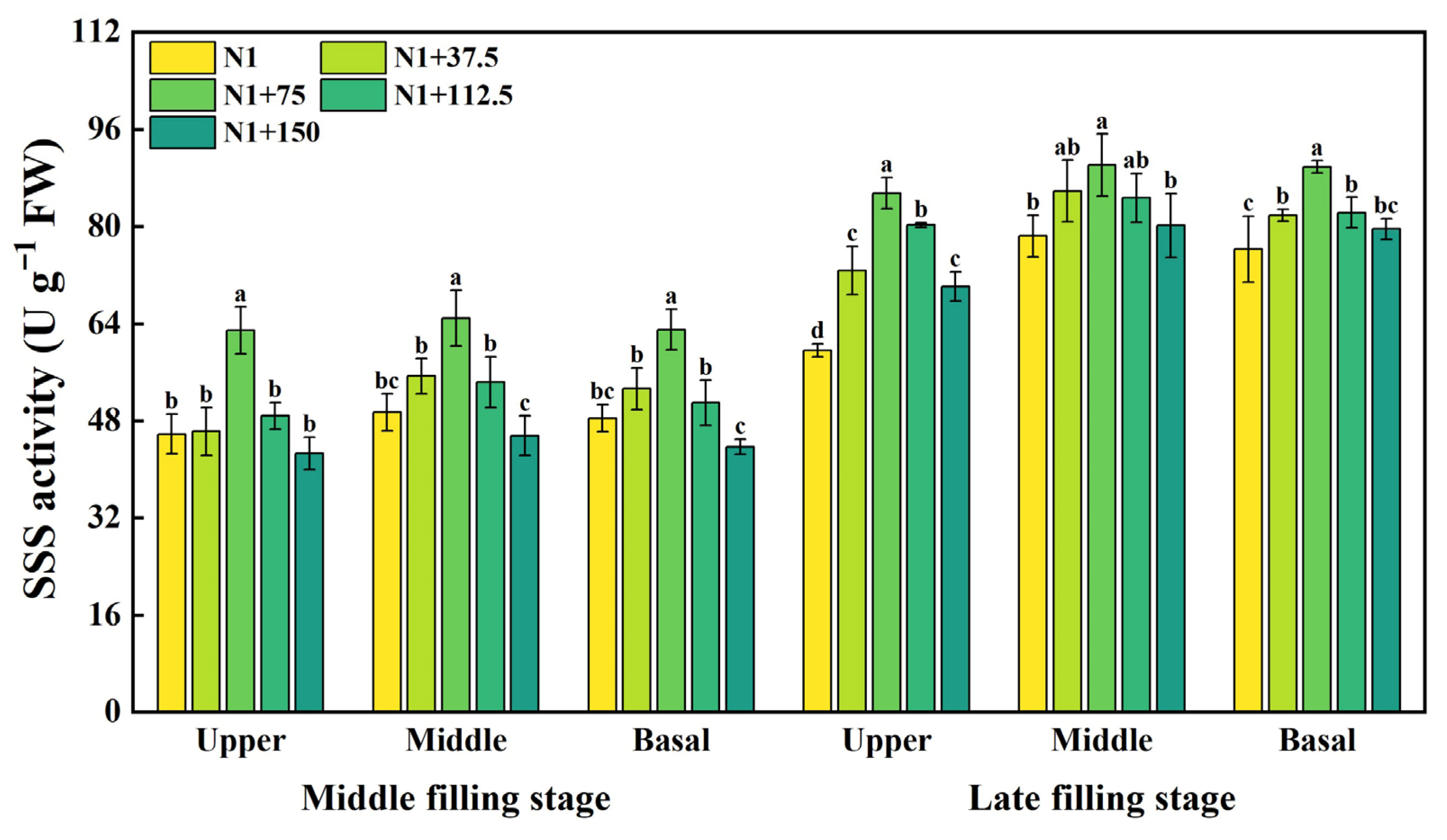

2.3. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the Enzyme Activity of SSS in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

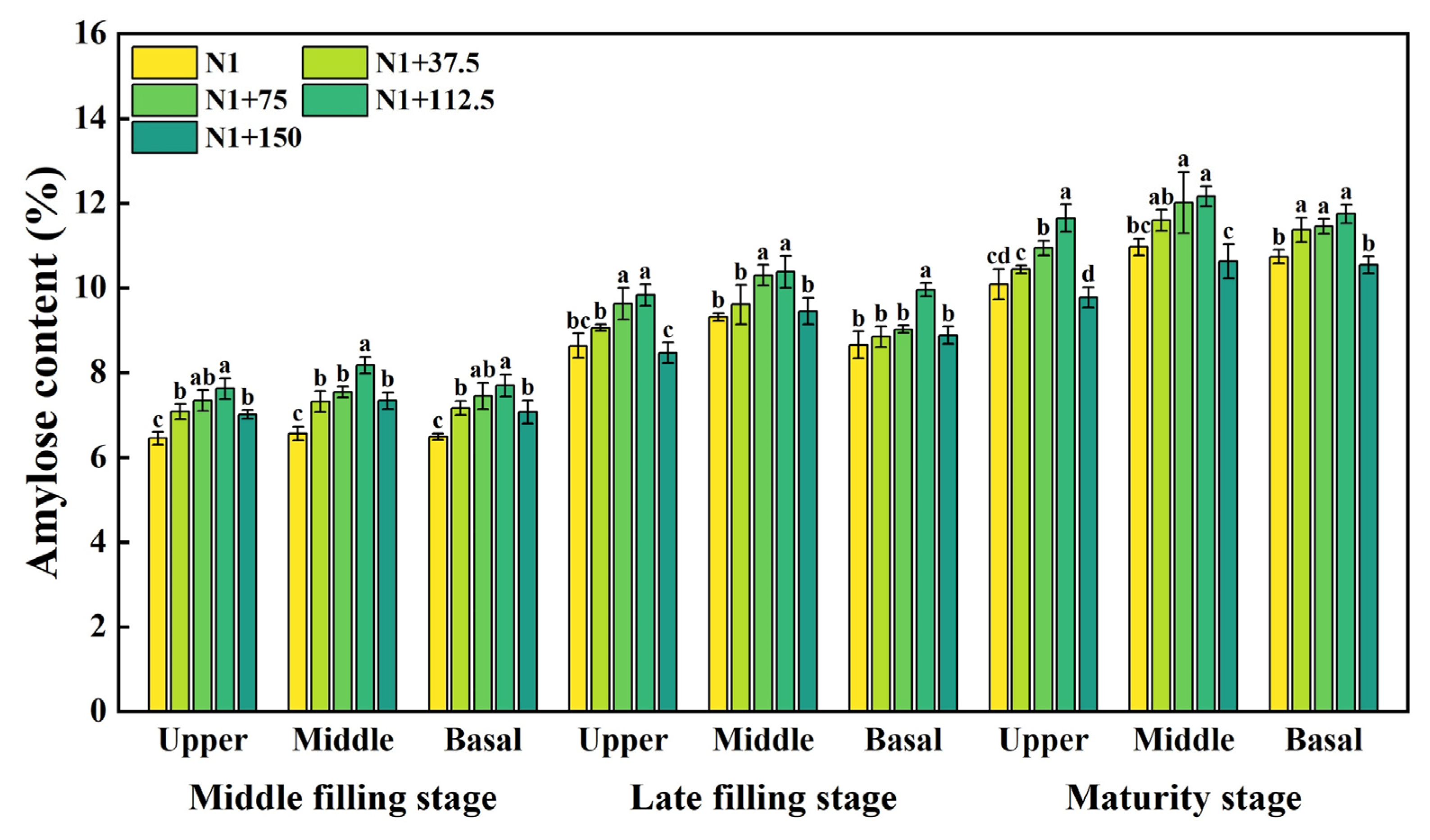

2.4. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the Amylose Content in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

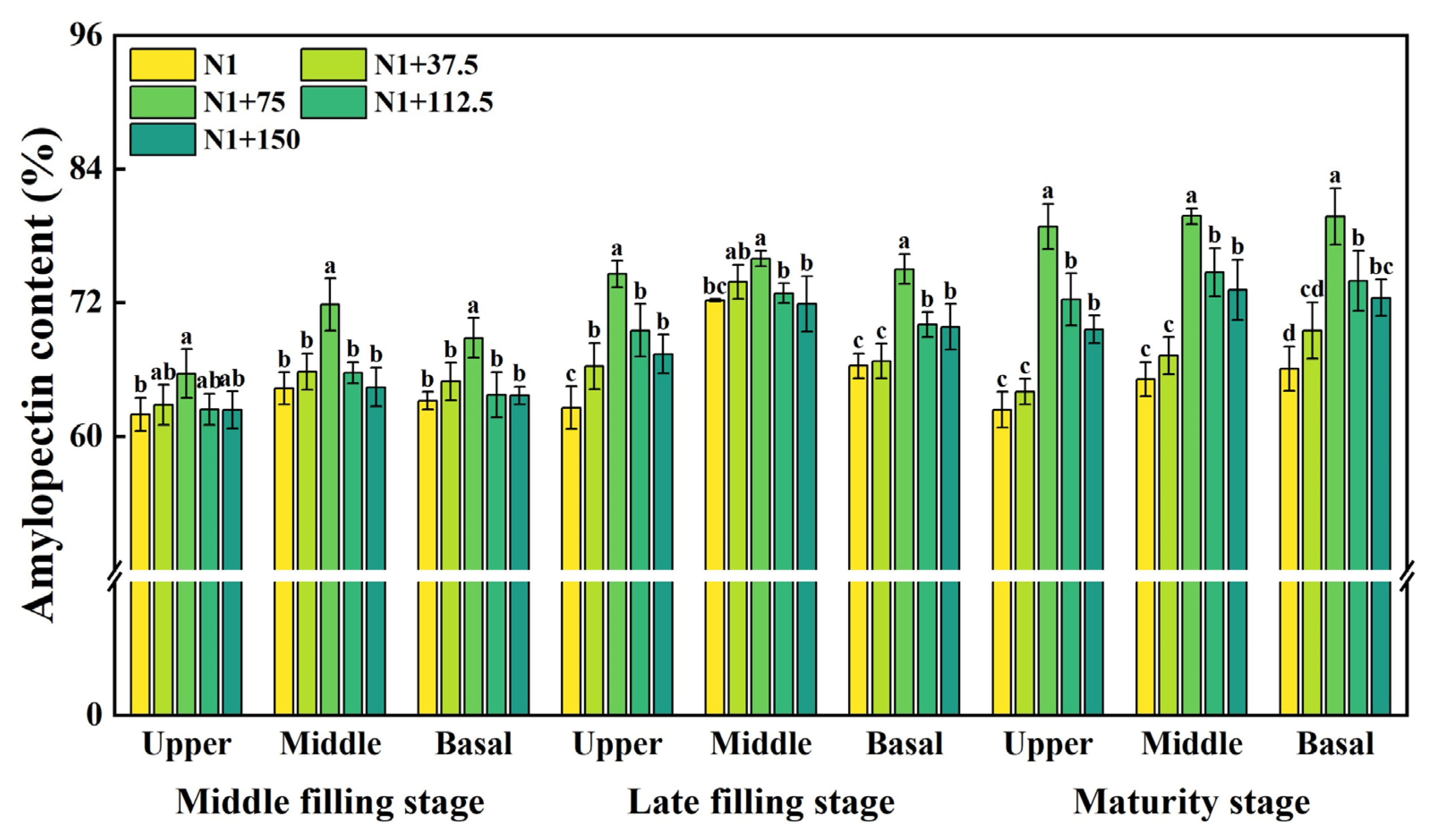

2.5. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the Amylopectin Content in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

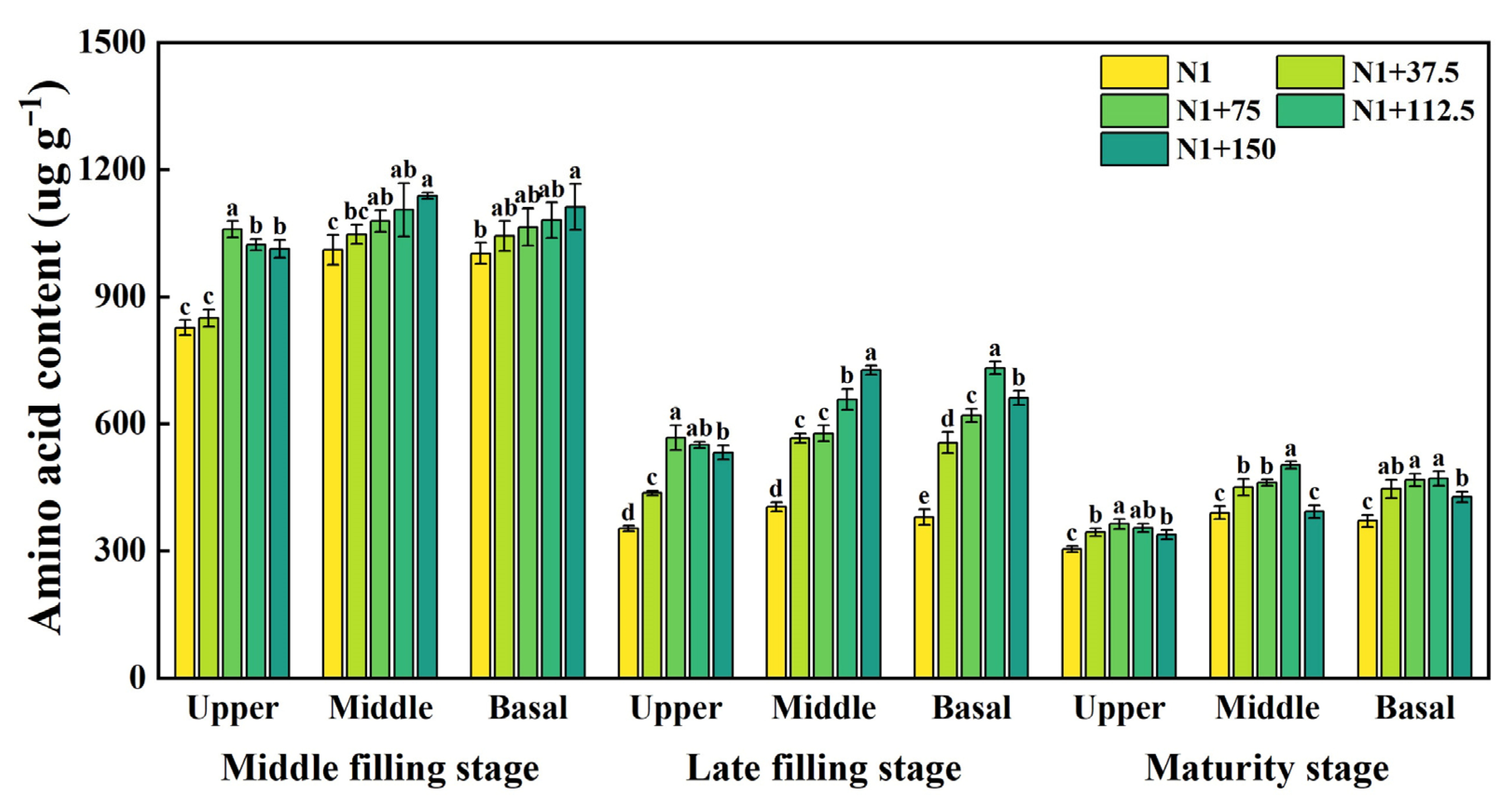

2.6. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the Amino Acid Content in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

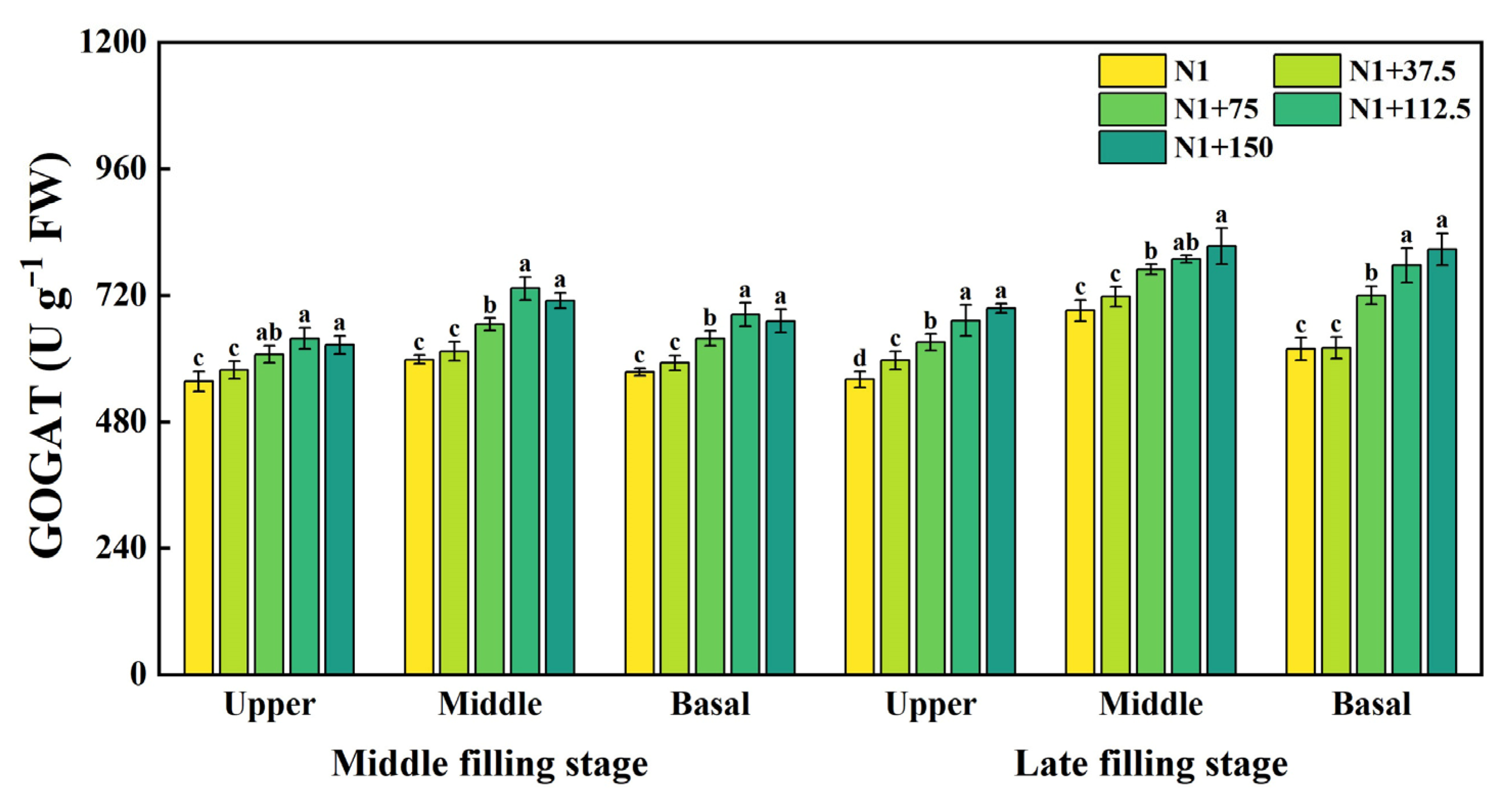

2.7. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the GOGAT Activity in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

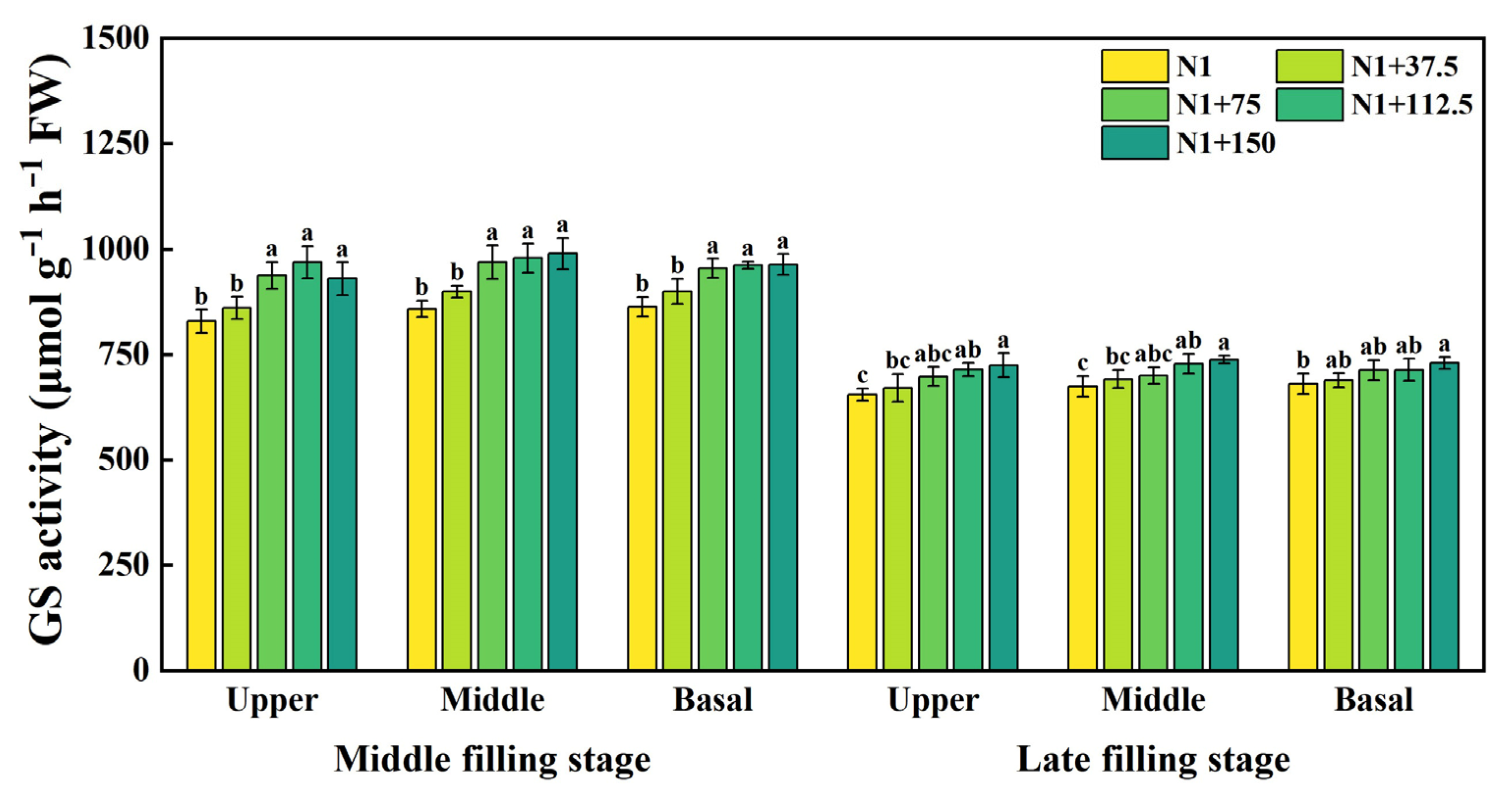

2.8. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the GS Activity in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

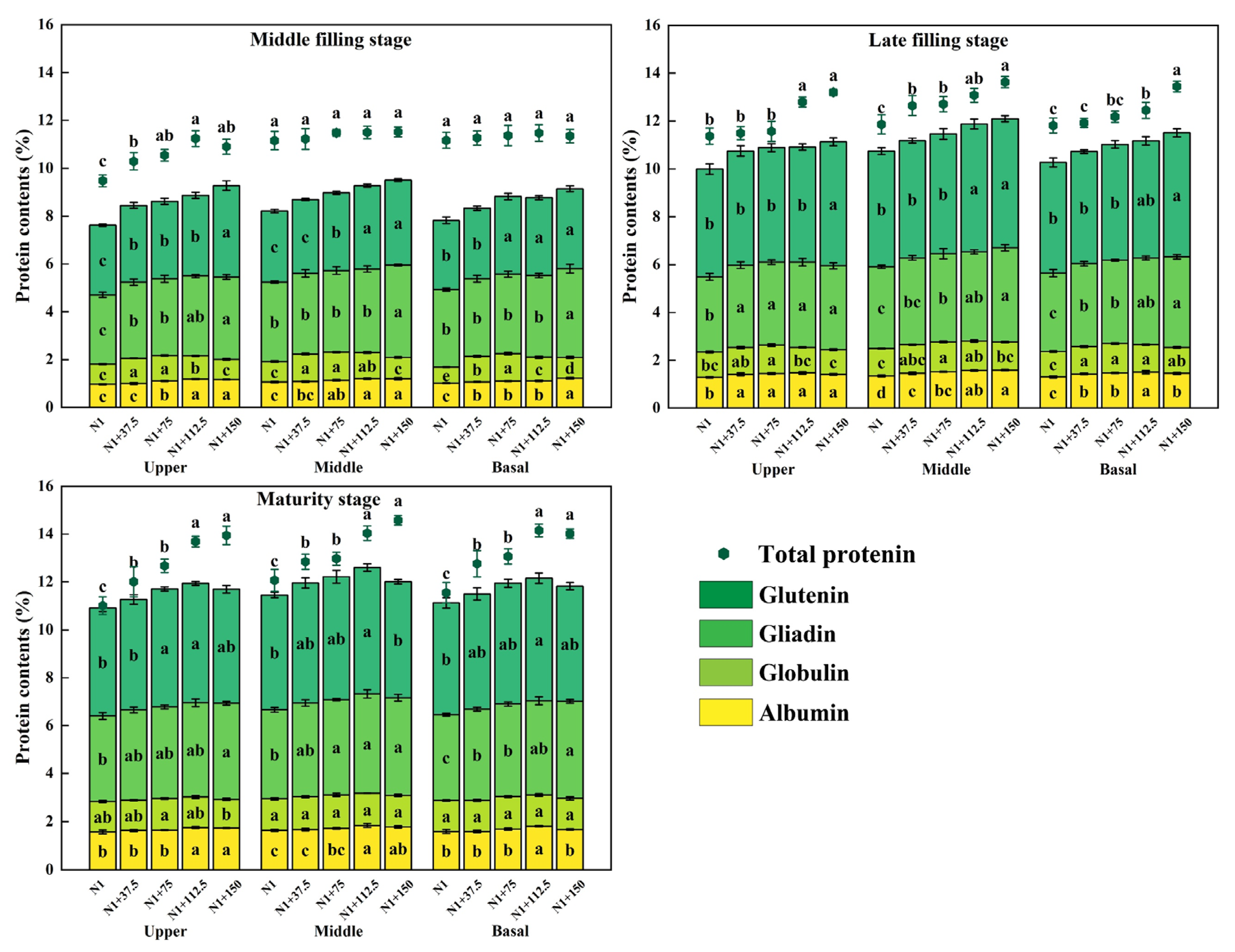

2.9. Effects of Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on the Protein Component Content in Grains at Differential Spike Positions

2.10. Effects of Different Nitrogen Topdressing Rates on Grain Yield and Yield Components

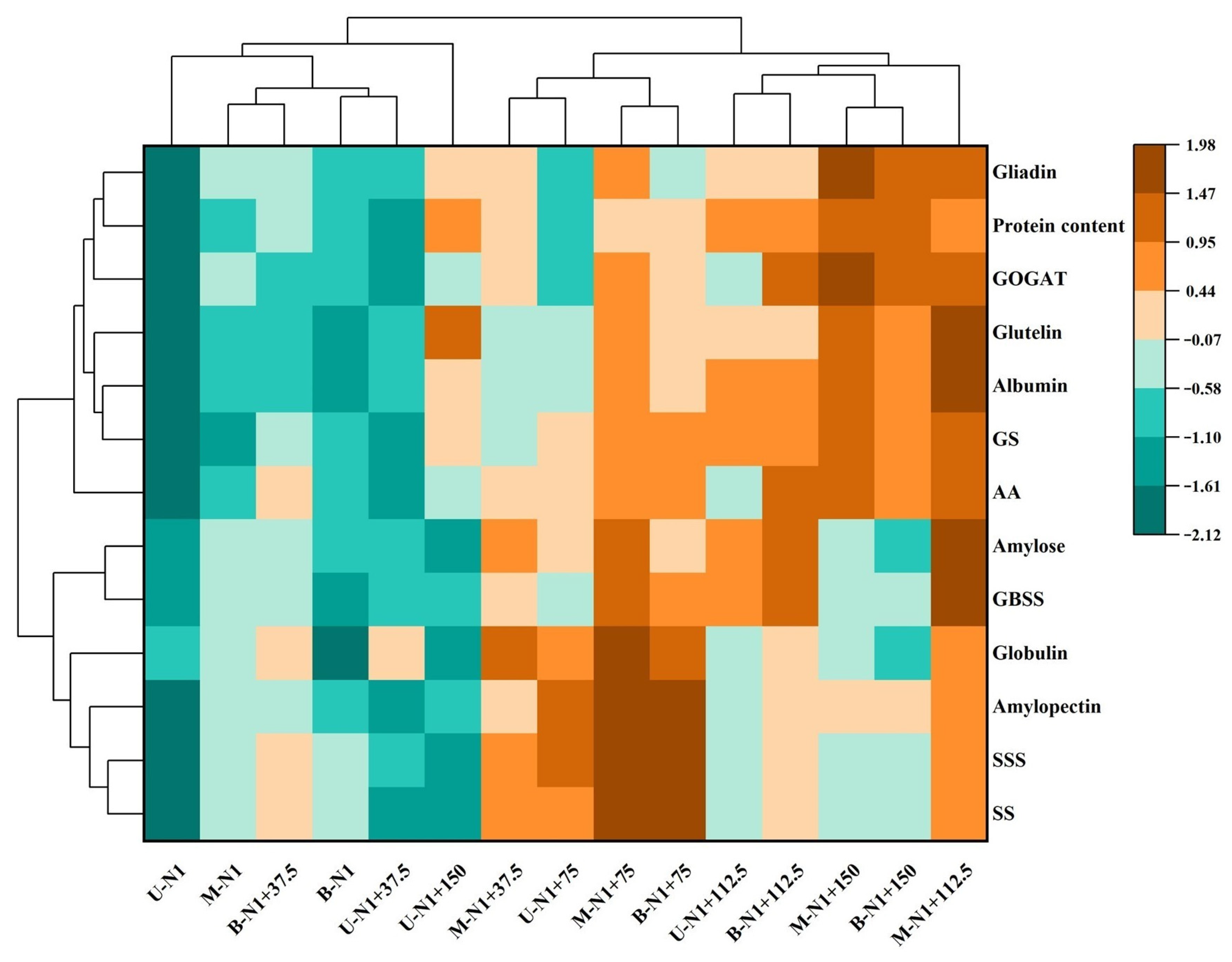

2.11. Cluster Analysis of Physiological and Biochemical Traits of Wheat Grain

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Nitrogen Management on Sugar Content and Starch Properties in Grains at Different Spike Positions

3.2. Effects of Nitrogen Management on Nitrogen Metabolism and Protein Components in Grains at Different Spike Positions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

4.2. Sampling and Measurements

4.2.1. Soluble Sugar Contents

4.2.2. Amylose and Amylopectin Contents

4.2.3. Contents of Free Amino Acid (FAA)

4.2.4. Determination of Related Enzymes in Grain Starch and Protein Synthesis

4.2.5. Grain Yield and Yield Components

4.2.6. Contents of Protein Components

4.2.7. Determination of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Liu, M.; Hebelstrup, K.H.; Yang, D.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, W.; et al. Nitrogen topdressing timing modifies the gluten quality and grain hardness related protein levels as revealed by iTRAQ. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wei, J.; Ran, L.; Liu, P.; Xiong, F.; Yu, X. The accumulation and properties of starch are associated with the development of nutrient transport tissues at grain positions in the spikelet of wheat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, C.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Dai, T.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, D. Screening of superior wheat lines under nitrogen regulation and factors affecting grain quality improvement under high yield. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 118, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, S.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yu, M.; Ma, X. Nitrogen Regulating the Expression and Localization of Four Glutamine Synthetase Isoforms in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, G.; Xiong, F. Agronomic Traits and Physicochemical Properties of Starch of Different Grain Positions in Wheat Spike Under Nitrogen Treatment. Starch-Stärke 2022, 74, 2100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Deng, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, G.; Lv, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Yan, Y. Comparative Phosphoproteomic Analysis under High-Nitrogen Fertilizer Reveals Central Phosphoproteins Promoting Wheat Grain Starch and Protein Synthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Cao, C.; Jiang, Y. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Starch Structure, Protein Distribution, and Quality of Rice. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 8, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 50, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Lu, F.; Pan, J.; Cui, Z.; Zou, C.; Chen, X.; He, M.; Wang, Z. The effects of cultivar and nitrogen management on wheat yield and nitrogen use efficiency in the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2015, 171, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, L.; Ma, W.; Wu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, F. What has caused the use of fertilizers to skyrocket in China? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 2, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, X. Integrated N management improves nitrogen use efficiency and economics in a winter wheat–summer maize multiple-cropping system. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2019, 3, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnér, K.; Weih, M.; Eriksson, J.; Kirchmann, H. Influence of nitrogen supply on macro- and micronutrient accumulation during growth of winter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2017, 213, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, N.R.; Costa, J.L.; Balzarini, M.; Castro Franco, M.; Córdoba, M.; Bullock, D. Delineation of management zones to improve nitrogen management of wheat. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 110, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.E.; Yue, S.; Schulz, R.; He, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Müller, T. Yield and N use efficiency of a maize–wheat cropping system as affected by different fertilizer management strategies in a farmer’s field of the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2015, 174, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C.-M.; Xue, C.; Sun, Z.; Ma, W. Booting stage is the key timing for split nitrogen application in improving grain yield and quality of wheat—A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2022, 287, 108665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Jiao, X. A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Nitrogen Management on Winter Wheat Yield and Quality. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2021, 11, 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, N.; Sadras, V.O.; Lollato, R.P. Late-season nitrogen application increases grain protein concentration and is neutral for yield in wheat. A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2023, 290, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Yang, S.; Ma, A.; Lunzhu, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Guo, S. Grain chalkiness is reduced by coordinating the biosynthesis of protein and starch in fragrant rice (Oryza sativa L.) grain under nitrogen fertilization. Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.L.B.; Antonangelo, J.A.; de Oliveira Silva, A.; Reed, V.; Arnall, B. Recovery of Grain Yield and Protein with Fertilizer Application Post Nitrogen Stress in Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lollato, R.P.; Jaenisch, B.R.; Silva, S.R. Genotype-specific nitrogen uptake dynamics and fertilizer management explain contrasting wheat protein concentration. Crop Sci. 2021, 3, 2048–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Zou, J.; Deng, J.; Pan, J.; Xiong, F. Analysis of development, accumulation and structural characteristics of starch granule in wheat grain under nitrogen application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 3739–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, P.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xu, F.; Guo, X.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Grain Chalkiness Is Decreased by Balancing the Synthesis of Protein and Starch in Hybrid Indica Rice Grains under Nitrogen Fertilization. Foods 2024, 13, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, M.; Wu, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Ji, Y.; Sun, X. Grain chalkiness traits is affected by the synthesis and dynamic accumulation of the storage protein in rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 14, 6125–6133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cao, X.; Song, J.; Liu, P.; Chen, D.; Liu, A.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z. Effects of Spikelet and Grain Positions on Grain Weight and Protein Content of Different Wheat Varieties. Acta Agron. Sin. 2017, 43, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yuan, X.; Yan, F.; Xiang, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, L.; Fan, P.; Yang, Z.; et al. Nitrogen Application Rate Affects the Accumulation of Carbohydrates in Functional Leaves and Grains to Improve Grain Filling and Reduce the Occurrence of Chalkiness. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 921130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, N.; Hao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer on yield and nitrogen use efficiency in winter wheat-summer maize rotation system. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2019, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, D.; Liu, F.; Cai, J.; Dai, T.; Cao, W. Starch granules size distribution in superior and inferior grains of wheat is related to enzyme activities and their gene expressions during grain filling. J. Cereal Sci. 2010, 2, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.H.; Hanif, M. A Study of Floret Development in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Ann. Bot. 1973, 4, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, G.; Yu, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, G.; Xiong, F. Endosperm enrichment and physicochemical properties of superior and inferior grain starch in super hybrid rice. Plant Biol. 2020, 4, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Cao, W.; Dai, T.; Jing, Q. Activities of key enzymes for starch synthesis in relation to growth of superior and inferior grains on winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) spike. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 3, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liu, W. High nitrogen application rate and planting density reduce wheat grain yield by reducing filling rate of inferior grain in middle spikelets. Crop J. 2021, 2, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Qin, Z.; Zheng, M.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Pang, D.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Involvement of ethylene and polyamines biosynthesis and abdominal phloem tissues characters of wheat caryopsis during grain filling under stress conditions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 1, 46020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Guo, X.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, X.; Dai, X.; He, M. Effect of delayed sowing on grain number, grain weight, and protein concentration of wheat grains at specific positions within spikes. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 8, 2359–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chang, X.; Wang, D.; Llu, X.; Yang, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhao, G. Effects of drought stress on material transportation and grain yield at different panicle positions of winter wheat. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2024, 6, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, B.; Song, J.; Lv, G.; Ji, B.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z.; Bai, W. Effect of dry-hot wind on grain weight of winter wheat at different spikelet and grain positions. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 2021, 42, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huarancca Reyes, T.; Scartazza, A.; Lu, Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Guglielminetti, L. Effect of carbon/nitrogen ratio on carbohydrate metabolism and light energy dissipation mechanisms in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 105, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, S.A.; Huang, Y.; Ali, S.; Hafeez, A.; Shah, A.N.; Song, X.; Ma, X.; Luo, D.; Yang, G. Mepiquat chloride application does not favor leaf photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism as well as lint yield in late-planted cotton at high plant density. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, L.; Ding, Y.; Weng, F.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Tang, S.; Ding, C.; Wang, S. Top-dressing nitrogen fertilizer rate contributes to decrease culm physical strength by reducing structural carbohydrate content in japonica rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 5, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liao, P.; Wang, W.; Xu, K.; Dai, Q.; et al. Excessive Nitrogen Application Leads to Lower Rice Yield and Grain Quality by Inhibiting the Grain Filling of Inferior Grains. Agriculture 2022, 12, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharwood, R.E.; Crous, K.Y.; Whitney, S.M.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Ghannoum, O. Linking photosynthesis and leaf N allocation under future elevated CO2 and climate warming in Eucalyptus globulus. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 5, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, H.; Kasuga, S.; Kawahigashi, H. Root lodging is a physical stress that changes gene expression from sucrose accumulation to degradation in sorghum. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, S.; Liang, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, S.; Wang, Z.; Ma, B.; Li, M. Nitrogen Levels Regulate Sugar Metabolism and Transport in the Shoot Tips of Crabapple Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 626149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; He, Z. Understanding the regulation of cereal grain filling: The way forward. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 2, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, T. Wheat Grain Yield Increase in Response to Pre-Anthesis Foliar Application of 6-Benzylaminopurine Is Dependent on Floret Development. PLoS ONE 2016, 6, e0156627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Mi, L.; Xu, K.; Wu, J.; Fan, Y.; Ma, S.; Jiang, D. Effects of Low Temperature at Booting Stage on Sucrose Metabolism and Endogenous Hormone Contents in Winter Wheat Spikelet. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.; Foulkes, J.; Furbank, R.; Griffiths, S.; King, J.; Murchie, E.; Parry, M.; Slafer, G. Achieving yield gains in wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 10, 1799–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Chen, P.; Xie, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Yang, J. Variations in Carbohydrate and Protein Accumulation among Spikelets at Different Positions Within a Panicle During Rice Grain Filling. Rice Sci. 2012, 3, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.B.; Badoghar, A.K.; Das, K.; Panigrahi, R.; Kariali, E.; Das, S.R.; Dash, S.K.; Shaw, B.P.; Mohapatra, P.K. Compact panicle architecture is detrimental for growth as well as sucrose synthase activity of developing rice kernels. Funct. Plant Biol. 2015, 9, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Zhao, S.; Jiao, G.; Duan, Y.; Ma, L.; Dong, N.; Lu, F.; Zhu, M.; Shao, G.; Hu, S.; et al. OPAQUE3, encoding a transmembrane bZIP transcription factor, regulates endosperm storage protein and starch biosynthesis in rice. Plant Commun. 2022, 6, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-R.; Huang, W.-X.; Cai, X.-L. Oligomerization of rice granule-bound starch synthase 1 modulates its activity regulation. Plant Sci. 2013, 210, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kötting, O.; Kossmann, J.; Zeeman, S.C.; Lloyd, J.R. Regulation of starch metabolism: The age of enlightenment? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 3, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, N.; Abe, N.; Oitome, N.F.; Matsushima, R.; Hayashi, M.; Tetlow, I.J.; Emes, M.J.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujita, N. Amylopectin biosynthetic enzymes from developing rice seed form enzymatically active protein complexes. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 15, 4469–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, K.; Li, L.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Anwar, S.; Fudjoe, S.K. Nitrogen Supply Affects Yield and Grain Filling of Maize by Regulating Starch Metabolizing Enzyme Activities and Endogenous Hormone Contents. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 798119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Beckles, D.M. Dynamic changes in the starch-sugar interconversion within plant source and sink tissues promote a better abiotic stress response. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 234, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, G.; Jaiswal, S.; Hucl, P.; Chibbar, R.N. Wheat genome specific granule-bound starch synthase I differentially influence grain starch synthesis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 114, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, J.; Subburaj, S.; Zhang, M.; Han, C.; Hao, P.; Li, X.; Yan, Y. Dynamic development of starch granules and the regulation of starch biosynthesis in Brachypodium distachyon: Comparison with common wheat and Aegilops peregrina. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 1, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Hu, L.; Ren, Y.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Paul, M.J.; Liu, Z. Nitrogen topdressing at panicle initiation modulated nitrogen allocation between storage proteins and free nitrogenous compounds in grains of japonica rice. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 119, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslam, M.; Mitsui, T.; Sueyoshi, K.; Ohyama, T. Recent Advances in Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in C3 Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ran, S.; Xu, R.; Lin, Y.; Shen, L.; Huang, W.; Zhong, F. Carbon and nitrogen metabolism in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) leaves response to nitrogen treatment. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 3, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Song, W.; Luo, D.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Lyu, W. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Endosperm Composition and Eating Quality of Rice Varieties with Different Protein Components. Agronomy 2024, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Muneer, M.A.; Chen, X.; Rasmussen, S.K.; Wu, L.; Cai, Y.; Cheng, F. Response of Phytic Acid to Nitrogen Application and Its Relation to Protein Content in Rice Grain. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Qiao, J.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. Distribution of proteins and amino acids in milled and brown rice as affected by nitrogen fertilization and genotype. J. Cereal Sci. 2010, 1, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, N.; Sadras, V.O.; Correndo, A.A.; Lollato, R.P. Cultivar-specific phenotypic plasticity of yield and grain protein concentration in response to nitrogen in winter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2024, 306, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Bin, S.; Iqbal, A.; He, L.; Wei, S.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, P.; Liang, H.; Ali, I.; Xie, D.; et al. High Sink Capacity Improves Rice Grain Yield by Promoting Nitrogen and Dry Matter Accumulation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divte, P.R.; Sharma, N.; Parveen, S.; Sellathdurai, D.; Anand, A. Interactive Effects of Post-Anthesis Foliar Nitrogen Management and Elevated Night Temperatures on Wheat Grain Nitrogen Metabolism. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2025, 30, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, Z. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer Rate on Nitrogen Metabolism and Protein Synthesis of Superior and Inferior Wheat Kernel. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2005, 38, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tea, I.; Genter, T.; Naulet, N.; Boyer, V.; Lummerzheim, M.; Kleiber, D. Effect of Foliar Sulfur and Nitrogen Fertilization on Wheat Storage Protein Composition and Dough Mixing Properties. Cereal Chem. 2004, 6, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flæte, N.E.S.; Hollung, K.; Ruud, L.; Sogn, T.; Færgestad, E.M.; Skarpeid, H.J.; Magnus, E.M.; Uhlen, A.K. Combined nitrogen and sulphur fertilisation and its effect on wheat quality and protein composition measured by SE-FPLC and proteomics. J. Cereal Sci. 2005, 3, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, A.E.; Lister, A.; Tomkins, M.; Adamski, N.M.; Simmonds, J.; Macaulay, I.; Morris, R.J.; Haerty, W.; Uauy, C. High expression of the MADS-box gene VRT2 increases the number of rudimentary basal spikelets in wheat. Plant Physiol. 2022, 3, 1536–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J. The Experiment Principle and Technique on Plant Physiology and Biochemistry; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, X.; Gu, S.; Wang, D. Supplemental irrigation at jointing improves spike formation of wheat tillers by regulating sugar distribution in ear and stem. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 279, 108160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, M.; Dai, T.; Jiang, D.; Cai, J. Effect of sulfur and potassium foliar applications on wheat grain protein quality. Field Crops Res. 2024, 319, 109639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, S.; Szłyk, E.; Jastrzębska, A. Simple extraction procedure for free amino acids determination in selected gluten-free flour samples. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 2, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Ren, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. Can wheat yield, N use efficiency and processing quality be improved simultaneously? Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 275, 108006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordas, C.A.; Sioulas, C. Dry matter and nitrogen accumulation, partitioning, and retranslocation in safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) as affected by nitrogen fertilization. Field Crops Res. 2009, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.5-2025; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Protein in Food. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Lu, R. Analysis Methods of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry; Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, G.; Huan, W.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J. Effects of straw incorporation and potassium fertilizer on crop yields, soil organic carbon, and active carbon in the rice–wheat system. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Spike Number (×104 ha−1) | Grain Number per Spike | 1000-Grain Weight (g) | Grain Yield (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 459.83 d | 38.76 b | 48.71 c | 7357.46 c |

| N1 + 37.5 | 483.05 cd | 40.26 b | 50.04 b | 8031.04 b |

| N1 + 75 | 564.96 b | 44.81 a | 50.71 ab | 9206.64 a |

| N1 + 112.5 | 630.57 a | 45.05 a | 51.53 a | 9451.74 a |

| N1 + 150 | 506.28 c | 42.69 ab | 47.58 c | 8076.03 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Jin, H.; Zhang, X.; Hao, Y.; Fang, B.; Zhang, D.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Yue, J.; Cheng, H.; et al. Nitrogen Topdressing Rate Alters Starch and Protein Properties in Grains at Different Spike Positions Under Long-Term Field Conditions. Plants 2025, 14, 3678. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233678

Wang J, Jin H, Zhang X, Hao Y, Fang B, Zhang D, Yang C, Wang H, Yue J, Cheng H, et al. Nitrogen Topdressing Rate Alters Starch and Protein Properties in Grains at Different Spike Positions Under Long-Term Field Conditions. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3678. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233678

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiarui, Haiyang Jin, Xiaoyan Zhang, Yonghui Hao, Baoting Fang, Deqi Zhang, Cheng Yang, Hanfang Wang, Junqin Yue, Hongjian Cheng, and et al. 2025. "Nitrogen Topdressing Rate Alters Starch and Protein Properties in Grains at Different Spike Positions Under Long-Term Field Conditions" Plants 14, no. 23: 3678. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233678

APA StyleWang, J., Jin, H., Zhang, X., Hao, Y., Fang, B., Zhang, D., Yang, C., Wang, H., Yue, J., Cheng, H., Zheng, F., & Li, X. (2025). Nitrogen Topdressing Rate Alters Starch and Protein Properties in Grains at Different Spike Positions Under Long-Term Field Conditions. Plants, 14(23), 3678. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233678