VrNAC25 Promotes Anthocyanin Synthesis in Mung Bean Sprouts Synergistically with VrMYB90

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of VrNAC25 Protein

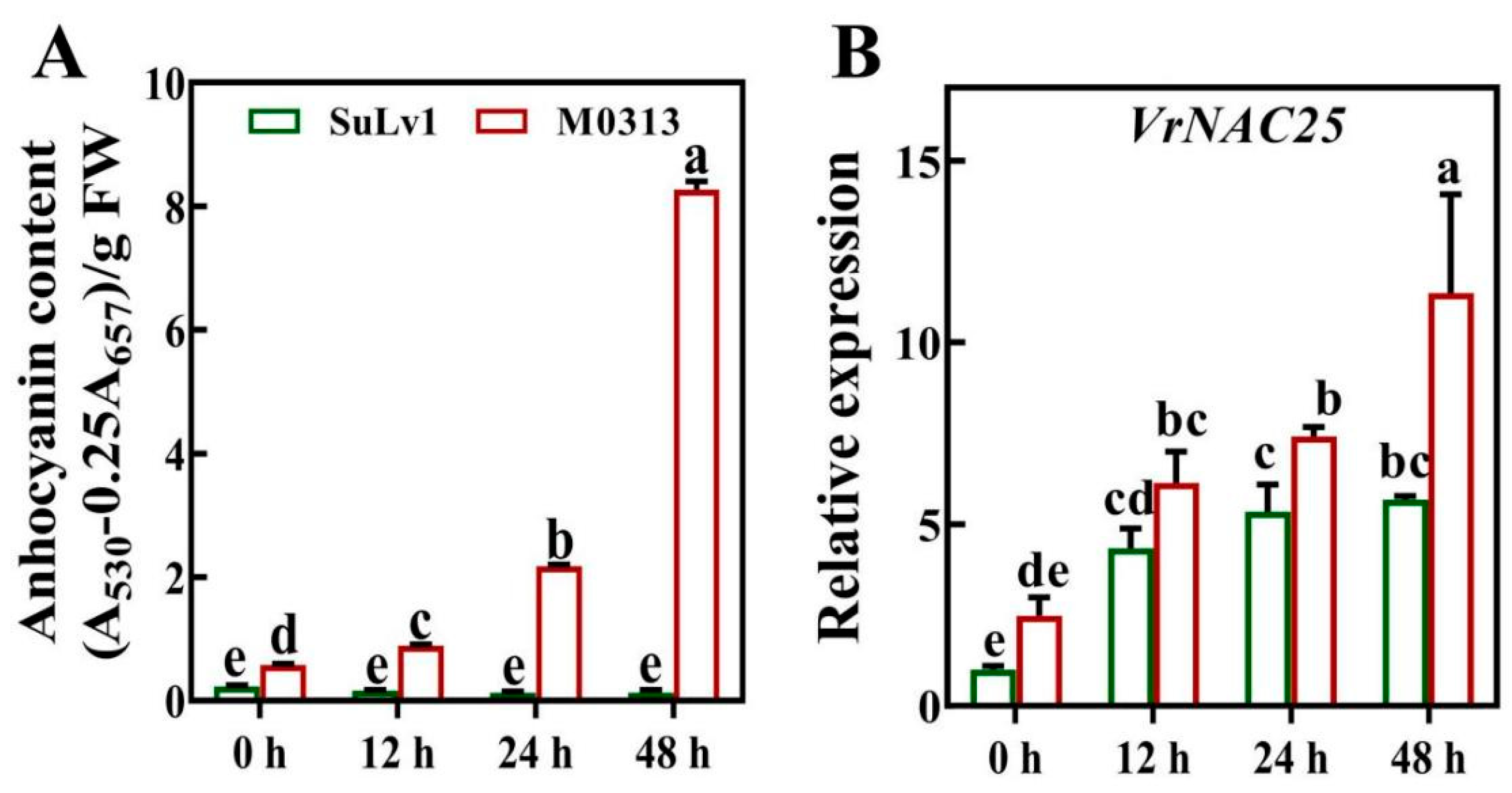

2.2. VrNAC25 Expression Is Highly Correlated with Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Mung Bean Sprouts

2.3. VrNAC25 Positively Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Mung Bean

2.4. VrNAC25 Cannot Directly Bind to the Promoters of VrDFR or VrLDOX

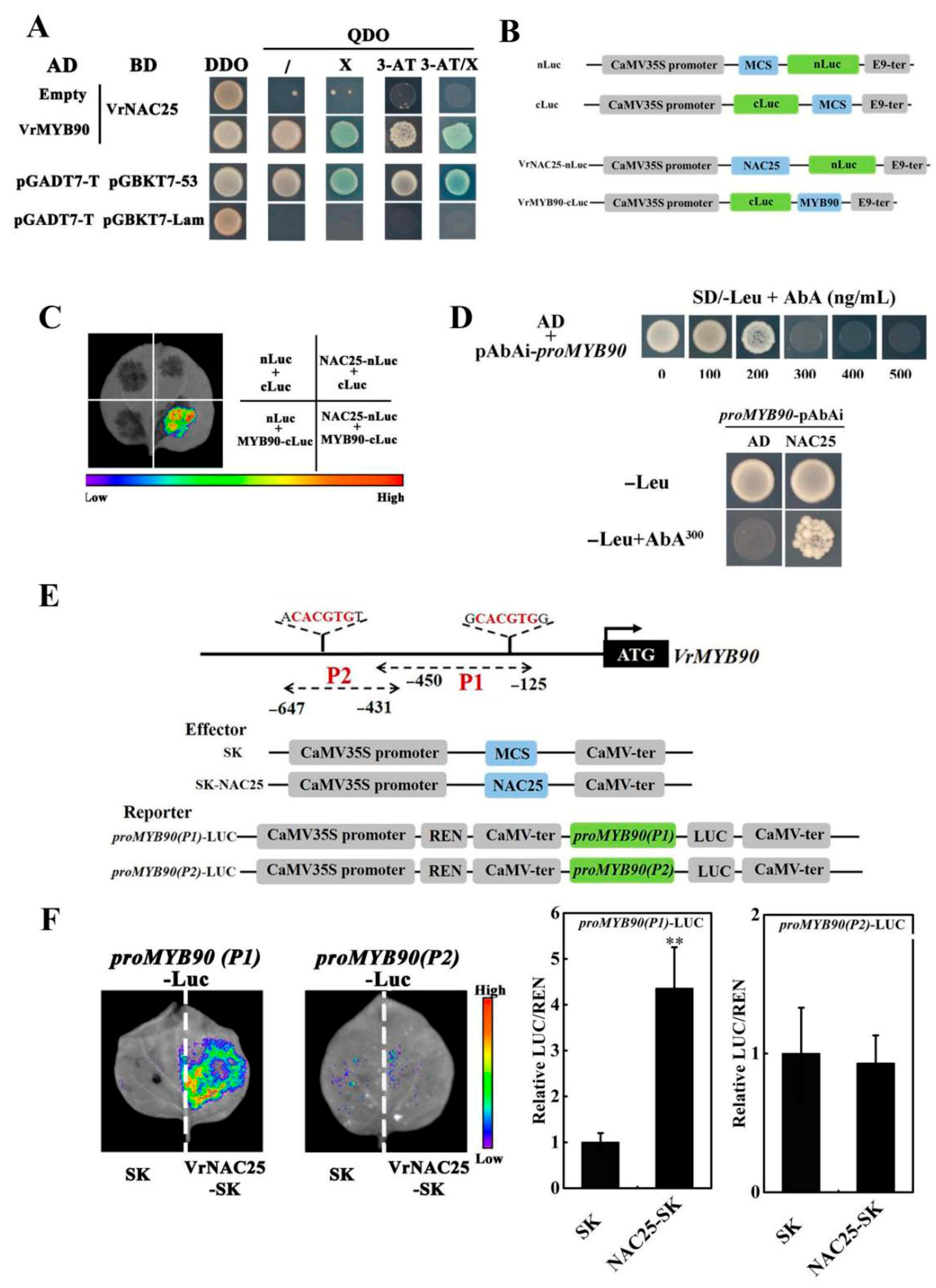

2.5. VrNAC25 Interacted with VrMYB90 at Both Protein Level and Transcription Level

2.6. The Interaction Between VrNAC25 and VrMYB90 Further Enhances the Positive Regulation of VrDFR and VrLDOX

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials and Cultivation Conditions

4.2. Determination of Anthocyanin Content

4.3. Extraction of Total RNA, DNA Digestion, and RNA Reverse Transcription

4.4. Protein Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Construction of VrNAC25

4.5. Subcellular Localization of VrNAC25 in Tobacco Cell

4.6. Transcriptional Activation Activity Analysis of VrNAC25

4.7. Yeast One-Hybrid Experiment

4.8. Yeast Two-Hybrid Experiment

4.9. Dual Luciferase Assay

4.10. Transient Expression Assays in Mung Bean Hairy Roots

4.11. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, R.H. Dietary bioactive compounds and their health implications. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, A18–A25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhir, R.; Lin, Y.T.; Shetty, K. Stimulation of phenolics, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities in dark germinated mung bean sprouts in response to peptide and phytochemical elicitors. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, J.J.; Smalley, J.V.; Dempsey, M.E. A phylogenetic examination of the primary anthocyanin production pathway of the Plantae. Bot. Stud. 2014, 55, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrede, G.; Wrolstad, R.E.; Lea, P.; Enersen, G. Color stability of strawberry and blackcurrant syrups. J. Food Sci. 1992, 57, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Ohmiya, A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: Anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 2008, 54, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broun, P. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis: A complex network of conserved regulators involved in multiple aspects of differentiation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005, 8, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Fang, H.; Zhang, J.; Su, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, N.; et al. Apple NAC transcription factor MdNAC52 regulates biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin through MdMYB9 and MdMYB11. Plant Sci. 2019, 289, 110286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Sharoni, A.M.; Kikuchi, S. Roles of NAC transcription factors in the regulation of biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooka, H.; Satoh, K.; Doi, K.; Nagata, T.; Otomo, Y.; Murakami, K.; Matsubara, K.; Osato, N.; Kawai, J.; Carninci, P.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2003, 10, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Xu, Z.; El-Kereamy, A.; Casaretto, J.A.; Rothstein, S.J. The Arabidopsis transcription factor ANAC032 represses anthocyanin biosynthesis in response to high sucrose and oxidative and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, T.; Kojima, Y.; Maruta, T.; Nishizawa-Yokoi, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor, ANAC078, regulates flavonoid biosynthesis under high-light. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 2210–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Allu, A.D.; Garapati, P.; Siddiqui, H.; Dortay, H.; Zanor, M.-I.; Asensi-Fabado, M.A.; Munné-Bosch, S.; Antonio, C.; Tohge, T.; et al. JUNGBRUNNEN1, a reactive oxygen species-responsive NAC transcription factor, regulates longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 482–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lin-Wang, K.; Wang, H.; Gu, C.; Dare, A.P.; Espley, R.V.; He, H.; Allan, A.C.; Han, Y. Molecular genetics of blood-fleshed peach reveals activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by NAC transcription factors. Plant J. 2015, 82, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhan, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Su, N.; Cui, J. VrMYB90 Functions Synergistically with VrbHLHA and VrMYB3 to Regulate Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Mung Bean. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lian, W.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Qi, C.; Liu, L.; Qin, S.; Yuan, X.; Li, X.; et al. Overexpression of BoNAC019, a NAC transcription factor from Brassica oleracea, negatively regulates the dehydration response and anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 13349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, C.; Yu, J.; Li, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, S.; Su, H.; Wang, L. A novel NAC transcription factor, MdNAC42, regulates anthocyanin accumulation in red-fleshed apple by interacting with MdMYB10. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Montesino, R.; Bouza-Morcillo, L.; Marquez, J.; Ghita, M.; Duran-Nebreda, S.; Gómez, L.; Holdsworth, M.J.; Bassel, G.; Oñate-Sánchez, L. A regulatory module controlling GA mediated endosperm cell expansion is critical for seed germination in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2019, 12, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Chen, N.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Zhi, J.; Yu, B.; Liu, X.; Cao, B.; Qiu, Z. Anthocyanin Fruit encodes an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, SlAN2-like, activating the transcription of SlMYBATV to fine-tune anthocyanin content in tomato fruit. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 2048–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Huang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X. LcNAC13 physically interacts with LcR1MYB1 to coregulate anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes during litchi fruit ripening. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Hu, D.; Zhao, L.; Tang, J.; Huang, Q.; Jin, P.; Li, H.; Han, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yao, F.; et al. MYB44 competitively inhibits the formation of the MYB340-bHLH2-NAC56 complex to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in purple-fleshed sweet potato. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, W.; Xu, J.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y. Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Induced by MYB Transcription Factors in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, X.; An, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, W.; Li, M.; Chen, Q.; et al. Molecular mechanism of pear R2R3-MYB transcription factor PbMYB30 that dynamically regulates anthocyanin synthesis. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2025, 229, 110410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Jin, X.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Dang, Y.; Ren, H.; Sultan, A.; et al. VvLBD11/28 repress anthocyanins biosynthesis and intracellular transport to decrease their deposition in grape. Plant Physiol. 2025, 199, kiaf562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, P.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Hou, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Pu, Y.; Chu, S.; et al. GmMYB4 Positively Regulates Isoflavone Biosynthesis via the GmMAPK6-GmMYB4-MBW Module in Soybean. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Peng, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Song, A.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, F. CmNAC25 targets CmMYB6 to positively regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis during the post-flowering stage in chrysanthemum. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.; Niu, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Xiong, M.; Xie, L.; Mao, Z.; Guo, T.; et al. Photoexcited CRY1 physically interacts with ATG8 to regulate selective autophagy of HY5 and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ye, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, P. GLK2, a GOLDEN2-LIKE Transcription Factor, Directly Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation by Binding With Promoters of Key Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 7055–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xue, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, H. High light upregulates the expression of the duplicate glutathione S-transferase genes SbrGSTF10/11 to induce anthocyanin accumulation in Salix brachista. Plant Sci. 2025, 362, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaqami, M. The Splicing Factor SR45 Negatively Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation under High-Light Stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Life 2023, 13, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; You, F.; Wan, Z.; Guo, M.; Lu, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Jia, L.; et al. VrNAC25 Promotes Anthocyanin Synthesis in Mung Bean Sprouts Synergistically with VrMYB90. Plants 2025, 14, 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233667

Zhu Y, Liu Y, You F, Wan Z, Guo M, Lu M, Yang L, Wang X, Yang J, Jia L, et al. VrNAC25 Promotes Anthocyanin Synthesis in Mung Bean Sprouts Synergistically with VrMYB90. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233667

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yaolei, Yao Liu, Fangfang You, Zixin Wan, Meilian Guo, Menghan Lu, Lu Yang, Xuezhu Wang, Jiajun Yang, Li Jia, and et al. 2025. "VrNAC25 Promotes Anthocyanin Synthesis in Mung Bean Sprouts Synergistically with VrMYB90" Plants 14, no. 23: 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233667

APA StyleZhu, Y., Liu, Y., You, F., Wan, Z., Guo, M., Lu, M., Yang, L., Wang, X., Yang, J., Jia, L., & Su, N. (2025). VrNAC25 Promotes Anthocyanin Synthesis in Mung Bean Sprouts Synergistically with VrMYB90. Plants, 14(23), 3667. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233667