Artificial Domestication Enhances Bioactive Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity in Two Wild Asteraceae Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotypic Analysis of Wild Plants and Domesticated Plants

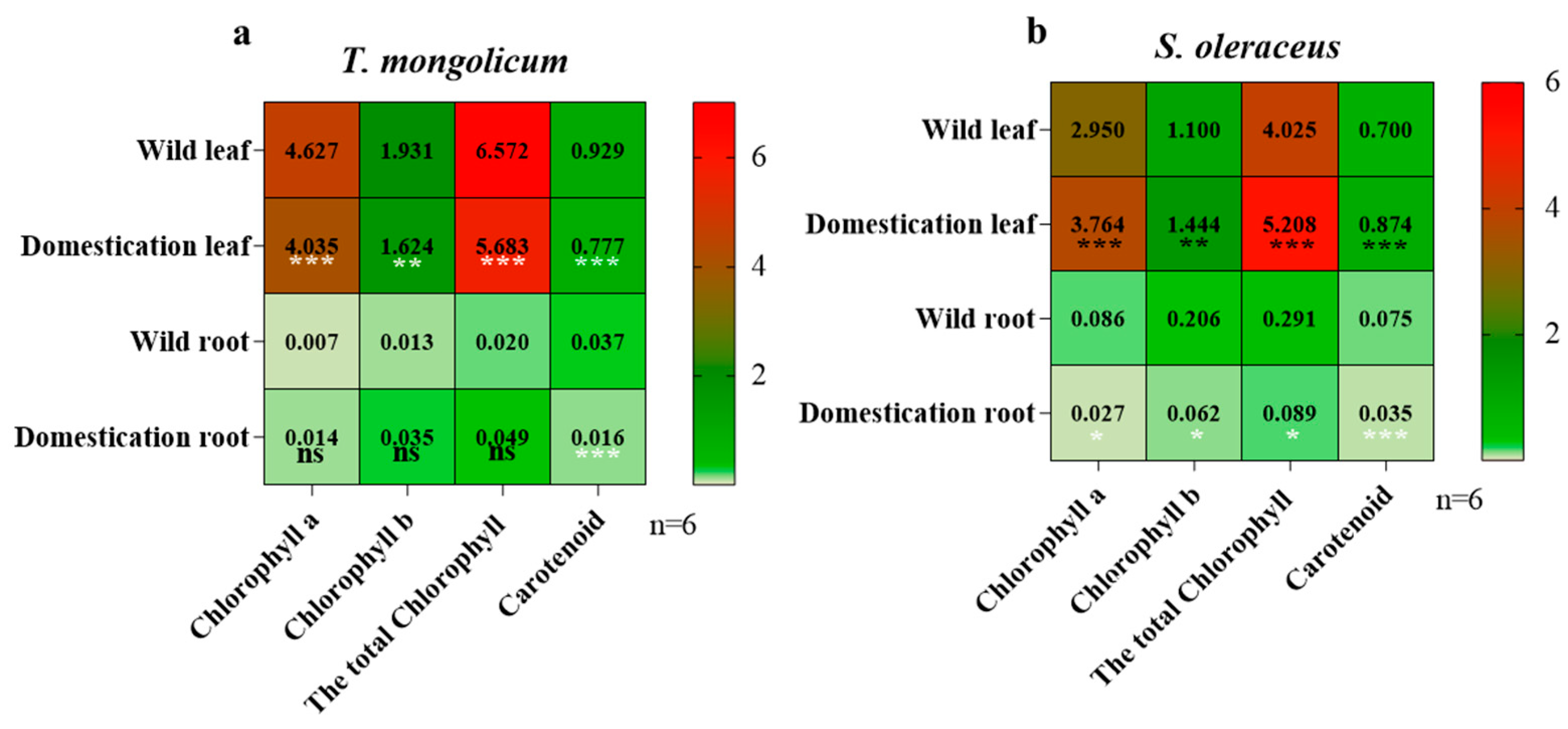

2.2. Analysis of Photosynthetic Pigments in Different Parts of Wild Plants and Domesticated Plants

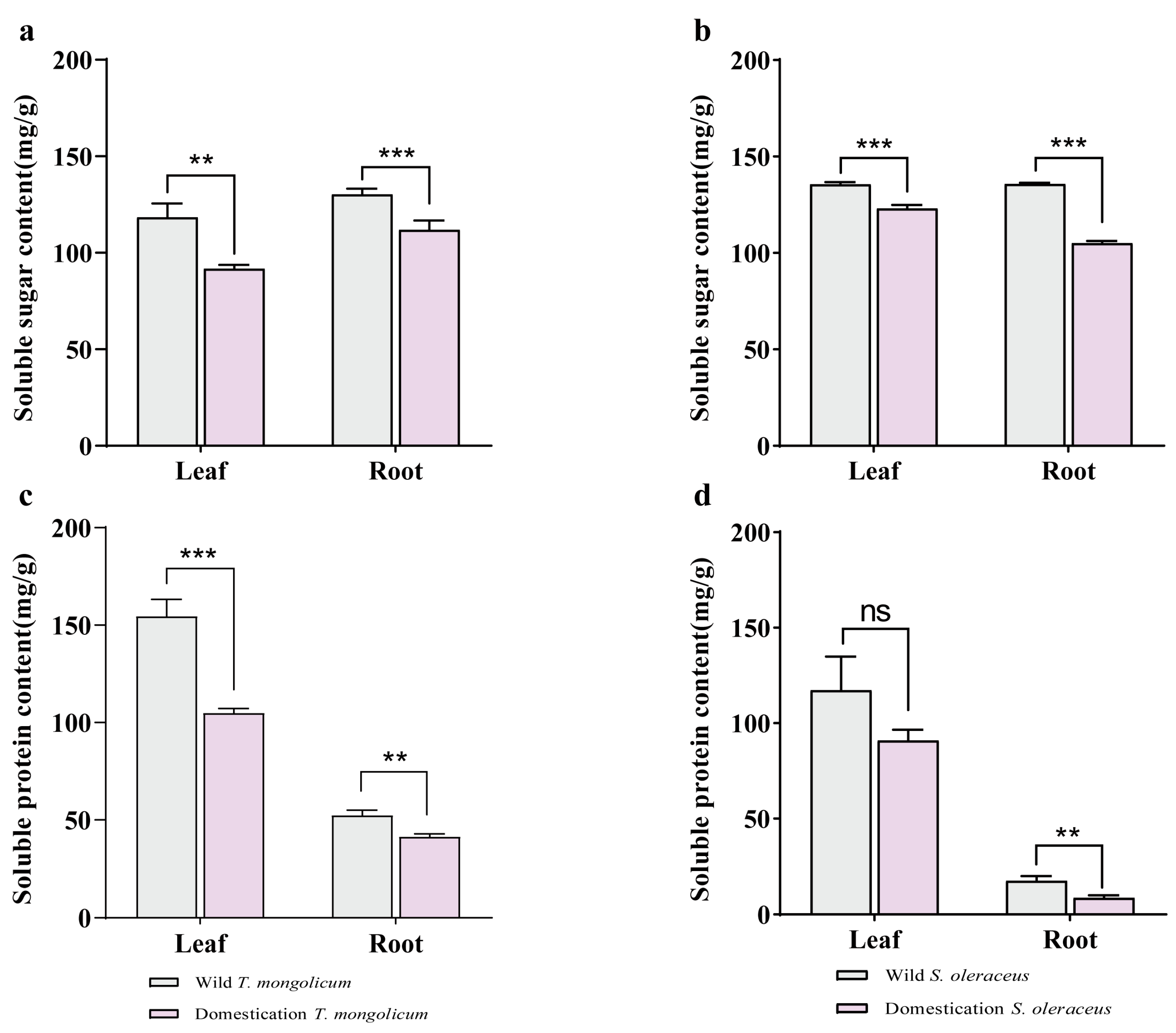

2.3. Analysis of Soluble Sugars and Soluble Proteins in Different Parts of Wild Plants and Artificially Domesticated Plants

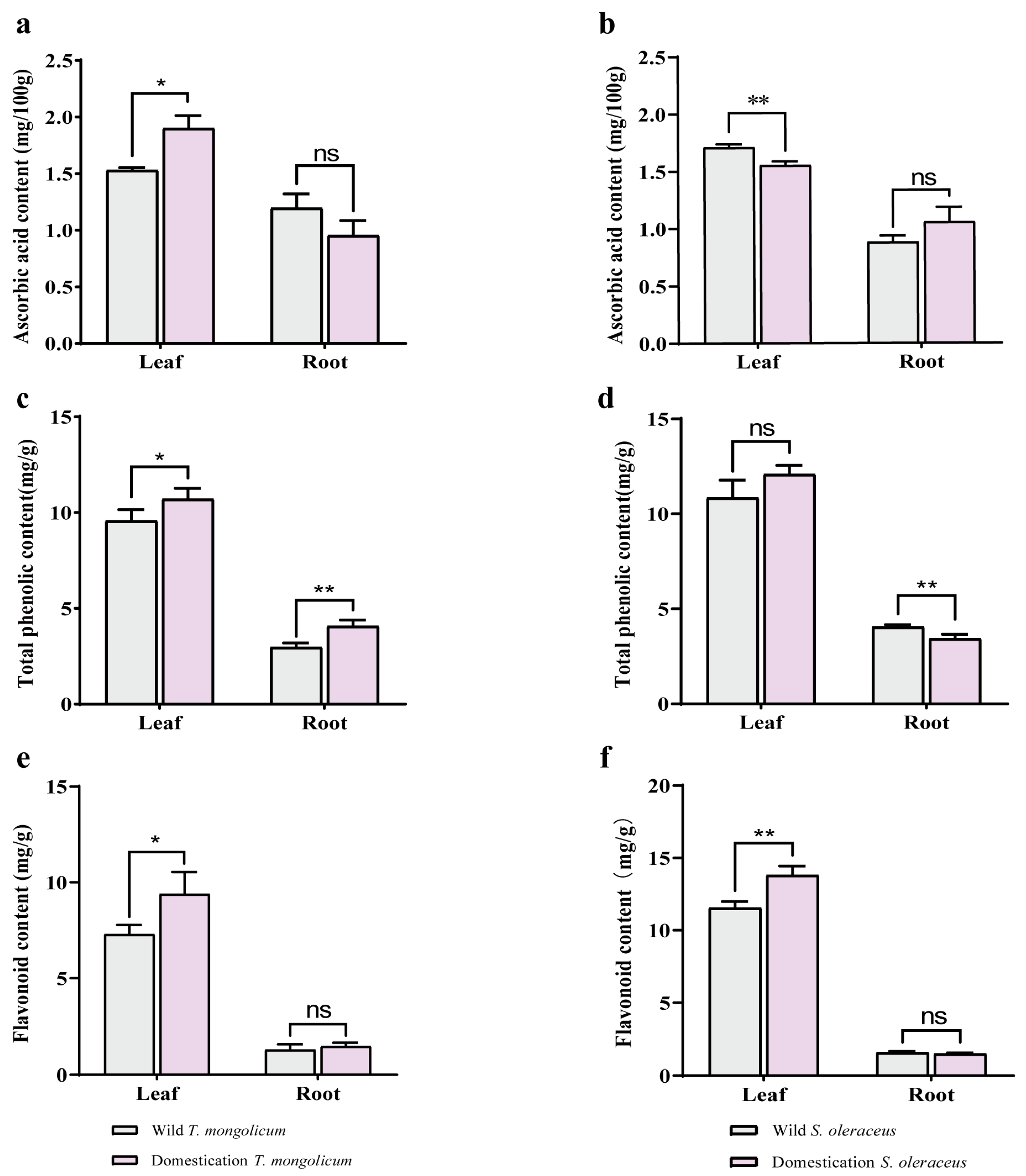

2.4. Antioxidant Components in Different Parts of Wild Plants and Domesticated Plants

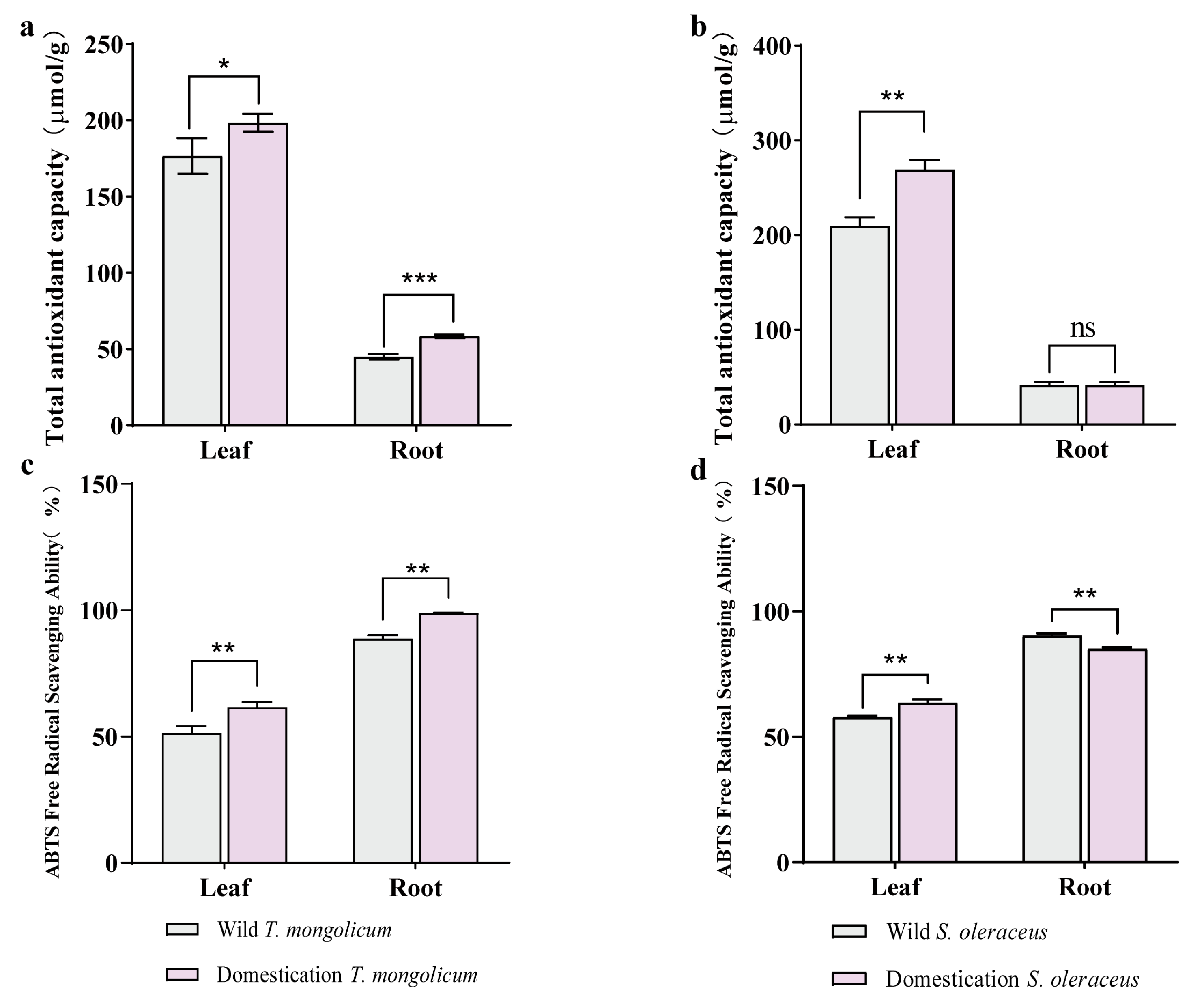

2.5. Antioxidant Capacity in Different Parts of Wild Plants and Domesticated Plants

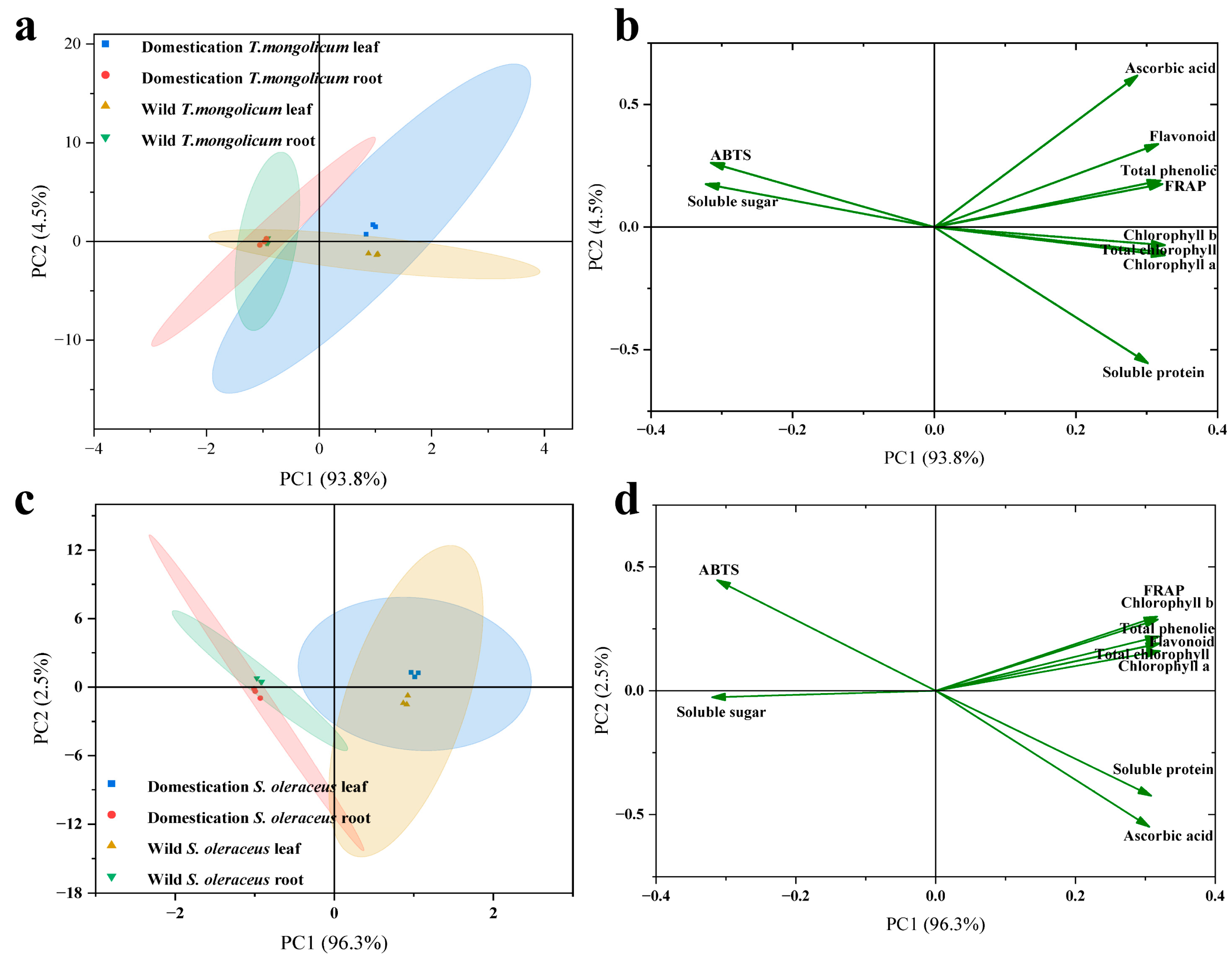

2.6. Principal Component Analysis of Components in Different Parts of Wild Plants and Artificially Domesticated Plants

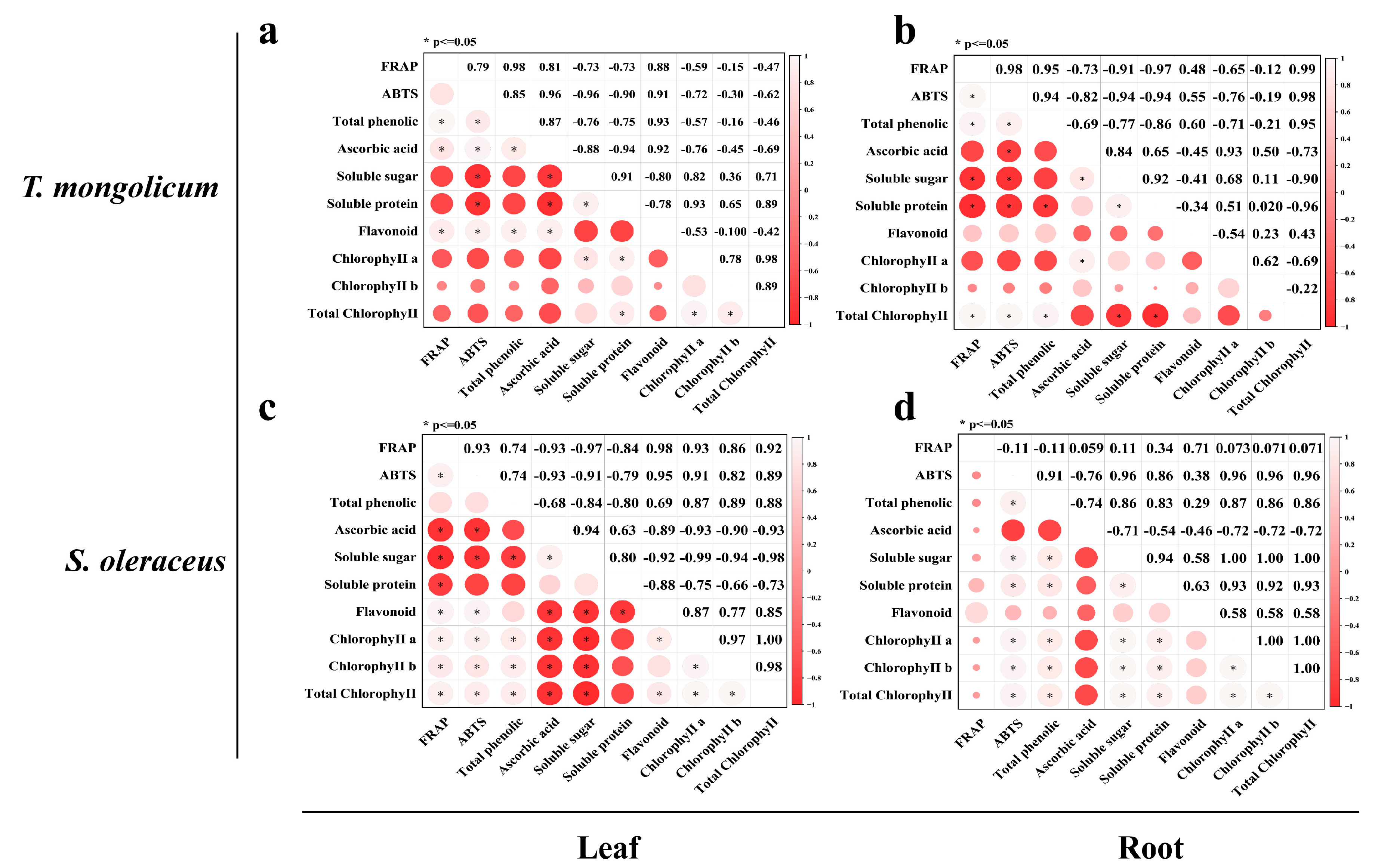

2.7. Correlation Analysis of Components in Different Parts of Wild Plants and Artificially Domesticated Plants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cultivation and Domestication of Wild Plants

4.2. Sample Collection and Growth Indicators

4.3. Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Content Determination

4.4. Soluble Sugar Content Determination

4.5. Soluble Protein Content Determination

4.6. Ascorbic Acid Content Determination

4.7. Total Phenolic Content Determination

4.8. Flavonoid Content Determination

4.9. FRAP Determination

4.10. ABTS+ Determination

4.11. Data Analysis and Processing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, K.; Su, S.L. Ethnobotanical study on wild edible plants in diet culture of Zhuang Nationality in Western Guangxi. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2017, 26, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, L.J.; Cui, S.J.; Zhu, Q.J.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Xiao, C.J. Study on in vitro Lipid-Lowering Activity of 33 Compositae Plants from West Yunnan. J. Dali Univ. 2022, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barreda, V.D.; Palazzesi, L.; Tellería, M.C.; Olivero, E.B.; Raine, J.I.; Forest, F. Early evolution of the angiosperm clade Asteraceae in the Cretaceous of Antarctica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10989–10994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.H.; Liu, H.R.; Deng, G.H. Processing technology of T. mongolicum tea. Shanghai Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.H.; Ma, J.Y.; Shim, S.H. Chemical constituents of the aerial part of Taraxacum mongolicum and their chemotaxonomic significance. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2303–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.G.; Cheng, S.F.; Li, Q.T.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.B. Research progress on extraction, isolation and biological activities of plant polysaccharides. Light Ind. ST 2023, 39, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Yan, Q.Z.; Tang, J.; Xia, B.H.; Lin, L.M.; He, Q.Z.; Liao, D.F. Study on chemical composition of volatile oil from Taraxaci Herba and its antiinflammatory and anti-tumor activities. China J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Pharm. 2018, 33, 3106–3111. [Google Scholar]

- Fioroto, M.A.; Toniazzo, T.; Giuntini, E.B.; Oliveira, P.V.; Purgatto, E. Mineral nutrients and protein composition of non-conventional food plants (Pereskia aculeata Miller, Sonchus oleraceus L. and Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 136, 106825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkanis, A.; Ntatsi, G.; Vasilakakou, E.; Karavidas, I.; Ntanasi, T.; Rumbos, C.I.; Athanassiou, C.G. Combining Tenebrio molitor frass with inorganic nitrogen fertilizer to improve soil properties, growth parameters, and nutrient content of Sonchus oleraceus crop. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 418, 131901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laabar, A.; Kabach, I.; Asri, S.E.; Kchikich, A.; Drioua, S.; Hamri, A.E.; Faouzi, M.E.A. Investigation of antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antiglycation properties of Sonchus oleraceus and Lobularia maritima(L.) Desv. extracts from Taza, Morocco. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, M.F.; El-Baset, M.A.; Khattab, A.R.; Taher, R.F.; El-Saied, M.A.; Elkarim, A.S.A.; Essa, A.F.; El-Rashedy, A.A.; Farag, M.A.; Imagawa, H. Hepatoprotective action of Sonchus oleraceus against paracetamol-induced toxicity via Nrf2/KEAP-1/HO-1 pathway in relation to its metabolite fingerprint and in silico studies. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.H.; Ren, J.Y.; Wang, P.; Duan, H.; Yang, Q.; Hou, M.J.; Gao, P. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of different parts from Sonchus oleraceus. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 2016, 44, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Idan, A.H.; Al-nayili, A.; Saady, N.M.C. Green synthesis of single phase of ZrO2 nanoparticles via Sonchus asper aqueous extract: Antibacterial, antioxidant, cytotoxic, and photocatalytic applications. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 4041–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkefle, N.N.; Zainal, N.; Wahyuni, D.K.; Mahmood, S.; Ramarao, K.D.R.; Chin, K.L. Antimicrobial properties of Sonchus species: A review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2025, 15, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissani, F.; Grara, N.; Guelmamene, R. Phytochemical screening and toxicity investigation of hydro-methanolic and aqueous extracts from aerial parts of Sonchus oleraceus L. in Swiss albino mice. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 31, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchia, C.A.D.; Locateli, G.; Serpa, P.Z.; Gomes, D.B.; Ernetti, J.; Miorando, D.; Zanatta, M.E.D.C.; Nunes, R.K.S.; Wildner, S.M.; Gutierrez, M.V. Sonchus oleraceus L. promotes gastroprotection in rodents via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antisecretory activities. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 7413231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Lin, M.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, X.S.; Qi, C.C.; Fan, R.Y.; Su, S.L.; Duan, J.L.; Liu, F.; Guo, S. Taraxacum mongolicum total triterpenoids and taraxasterol ameliorate benign prostatic hyperplasia by inhibiting androgen levels, inflammatory responses, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the TGFβ1/Smad signalling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 349, 119995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.R.; Guo, Y.; Deng, X.X.; Jiao, Y.N.; Hao, H.F.; Dong, Q.Q.; Sun, H.; Han, S.Y. Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz extract disrupts the interaction between triple-negative breast cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages by inhibiting RAC2/NF-κB p65/p38 MAPK pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 347, 119757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.J.F.; De Assis, R.M.A.; Rocha, J.P.M.; Cossa, M.C.V.; De Oliveira, T.; Coelho, A.D.; Da Silva, A.C.B.; Mendonca, S.C.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Pinto, J.E.B. Sow thistle (Sonchus oleraceus L.) propagation in vitro: Wavelength, photon flux density and natural ventilation effects on its growth and chicoric acid content. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 180, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendy, A.E.G.E.; Mohamed, N.A.; Sarker, T.C.; Hassan, E.M.; Garaa, A.H.; Elshamy, A.I.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M. Chemical composition, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activity of essential oils in the above-ground parts of Sonchus oleraceus L. Plants 2024, 13, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, Á.M.; Hellín, P.; Hernández, V.; Dabauza, M.; Robledo, A.; Sánchez, A.; Fenoll, J.; Flores, P. Chemical composition of wild collected and cultivated edible plants (Sonchus oleraceus L. and Sonchus tenerrimus L.). Plants 2024, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Song, M.; Wang, N.F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.F.; An, X.P.; Qi, J.W. The effects of solid-state fermentation on the content, composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of flavonoids from dandelion. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, G.Q.; Xie, J.Y.; Wu, M.Q.; Wang, W.H.; Xiao, L.; Qian, Z.M. Screening antioxidant components in different parts of dandelion using online gradient pressure liquid extraction coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography antioxidant analysis system and molecular simulations. Molecules 2024, 29, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, D.; Zhao, J.H.; Yan, L.; Feng, G.Z.; Gao, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhao, L.P. Soil pH is the primary factor driving the distribution and function of microorganisms in farmland soils in northeastern China. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, Z.G.; Xiao, J. Effects of different habitats on the growth, chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of medicinal and edible plants Sambucus chinensis Lind. Ecol. Sci. 2021, 40, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.D.; Liang, Z.S.; Pubu, Z.M.; Yang, Z.Q.; Han, R.L.; Xu, X.X. Flavonoids content and flavonoids synthetic key enzyme activities in Alfalfa under drought stress. Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occident. Sin. 2020, 40, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Jiang, J.Y.; Jiang, C.J.; Li, W. Effects of low temperature stress on SOD activity, soluble protein content and soluble sugar content in Camellia sinensis leaves. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2011, 38, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.L.; Li, H.Y.; Wu, H.W.; Liu, Z.X.; Wu, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H.X.; Yang, X.Y. Comparison on osmotica accumulation of different salt-tolerant plants under salt stress. For. Res. 2015, 28, 826–832. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, J.Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.Z.; Li, Y.; Hou, X.L.; Liu, T.K. Comparative analysis of nutritional quality of diploid and autotetraploid of 17 non-heading Chinese cabbage. Acta Agric. Shanghai 2025, 41, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.B.; Liu, Y.N.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.Y.; Ji, Y. Preliminary evaluation on cold tolerance of 8 Pennisetum forage varieties (lines) under natural low temperature. J. Grassl. Forage Sci. 2025, 2, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, L. Effects of Pig Manure Biogas Slurry Irrigation on Soil Quality and Growth of Four Vegetable Crops. Master’s Thesis, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.Q.; Yang, Y.J.; Guo, Z.L.; Qu, F. Effects of fertilization and density on soluble sugar and protein and nitrate reductase of hybrid foxtail millet. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2015, 21, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.P.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.J.; Huang, Y.P. Difference comparison of antioxidant activity among different varieties of Amaranth and Dandelion. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2014, 46, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.X. Effects of Planting Methods and Organic Fertilizer Application on the Growth and Quality of Dandelion. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.M.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Mao, J.Y.; Lei, B.; He, X.X.; Liu, X.B.; Li, P.X.; Pan, K. Effects of light intensity on growth, accumulation of active constituents and antioxidant activities of Taraxacum mongolicum Hand. Mazz. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 2023, 54, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.Y. Effects of Water Supply on the Quality and Functional Substances of Different Kinds of Sonchus oleraceus L. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi Agricultural University, Taiyuan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Anca, T.; Laurian, V.; Ilioara, O.; Dan, C.V.; Ana-Maria, G.; Ilioara, O. Solidago graminifolia L. Salisb. (Asteraceae) as a valuable source of bioactive polyphenols: HPLC profile, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. Molecules 2019, 24, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elżbieta, S.S.; Marlena, D.M.; Justyna, C.K.; Natasza, C.K.; Rafał, R.; Joanna, Ł.; Karolina, G.; Wiesława, B.; Janusz, W. Anti-inflammatory activity and phytochemical profile of Galinsoga parviflora Cav. Molecules 2018, 23, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Lou, L.Y.; Yin, P.; Huang, R.; Ye, X.Q.; Chen, J.C. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of five pickled and dried mustard brands. Food Sci. 2018, 12, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.J.; Shang, Y.H. Comparative analysis of active components and antioxidant capacity of different parts of blueberry. China Condim. 2024, 49, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.F.; Deng, Y.P.; Huang, Z.K.; Lai, Z.X. Bioactive substances and antioxidant activity in different-colored sprouts of cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L.). Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 31, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Vojvodić, S.; Božović, D.; Aćimović, M.; Gašić, U.; Zeković, Z.; Bebek Markovinović, A.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Zlatković, B.; Pavlić, B. A preliminary insight into under-researched plants from the Asteraceae family in the Balkan peninsula: Bioactive compound diversity and antioxidant potential. Plants 2025, 14, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.P.; Cai, S.N.; Chu, D.K.; Pang, R.; Deng, J.H.; Zheng, X.L.; Dai, W. Identification of chemical constituents in Blumea balsamifera using UPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS and evaluation of their antioxidant activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Di, H.M.; Zhang, J.Q.; Xia, P.X.; Huang, W.L.; Jian, Y.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhang, F. Effect of light on sensory quality, health-promoting phytochemicals and antioxidant capacity in post-harvest baby mustard. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 128057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, K.M. The application of the anthrone reagent to the estimation of starch in cereals. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1956, 7, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantization of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. Tyrosine and tryptophane in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1927, 73, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirie, A.; Mullins, M.G. Changes in anthocyanin and phenolics content of grapevine leaf and fruit tissues treated with sucrose, nitrate abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 1976, 58, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘antioxidant power’: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

”, this scale shows a length of 5 cm.

”, this scale shows a length of 5 cm.

”, this scale shows a length of 5 cm.

”, this scale shows a length of 5 cm.

| Varieties | Leaf Height (cm) | Leaf Width (cm) | Yield (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild T. mongolicum | 10.86 | 2.06 | 39,020 |

| Domestication T. mongolicum | 21.11 ** | 3.65 * | 51,870 ** |

| Wild S. oleraceus | 10.45 | 1.63 | 109,560 |

| Domestication S. oleraceus | 12.18 | 2.05 | 128,160 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, A.; Gao, H.; Wei, Z.; Sun, D.; Han, S.; Ren, X.; Wan, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, K.; Sun, B. Artificial Domestication Enhances Bioactive Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity in Two Wild Asteraceae Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233662

Zheng A, Gao H, Wei Z, Sun D, Han S, Ren X, Wan X, Cao Y, Wu K, Sun B. Artificial Domestication Enhances Bioactive Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity in Two Wild Asteraceae Plants. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233662

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Aihong, Hanfeng Gao, Zhixin Wei, Dongyang Sun, Shuyu Han, Xuling Ren, Xuhua Wan, Yonggang Cao, Keshun Wu, and Bo Sun. 2025. "Artificial Domestication Enhances Bioactive Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity in Two Wild Asteraceae Plants" Plants 14, no. 23: 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233662

APA StyleZheng, A., Gao, H., Wei, Z., Sun, D., Han, S., Ren, X., Wan, X., Cao, Y., Wu, K., & Sun, B. (2025). Artificial Domestication Enhances Bioactive Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity in Two Wild Asteraceae Plants. Plants, 14(23), 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233662