Organic Amendments and Trichoderma Change the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Improve Cucumber Yield and Fusarium Suppression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sequencing Data

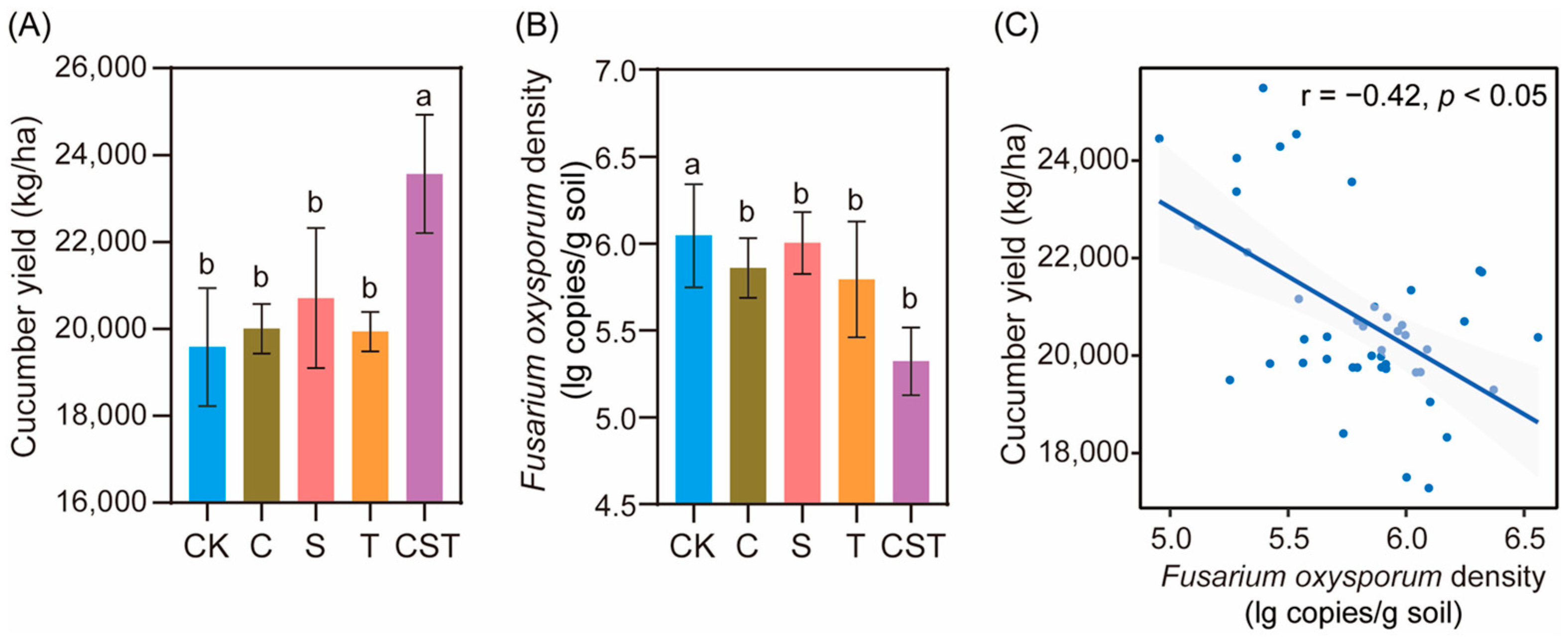

2.2. Effects of the Combined Application of Chitin, Straw, and Trichoderma on Crop Yield and Pathogen Density

2.3. Effects of the Combined Application of Chitin, Straw, and Trichoderma on Rhizosphere Microbial α Diversity and Community Composition

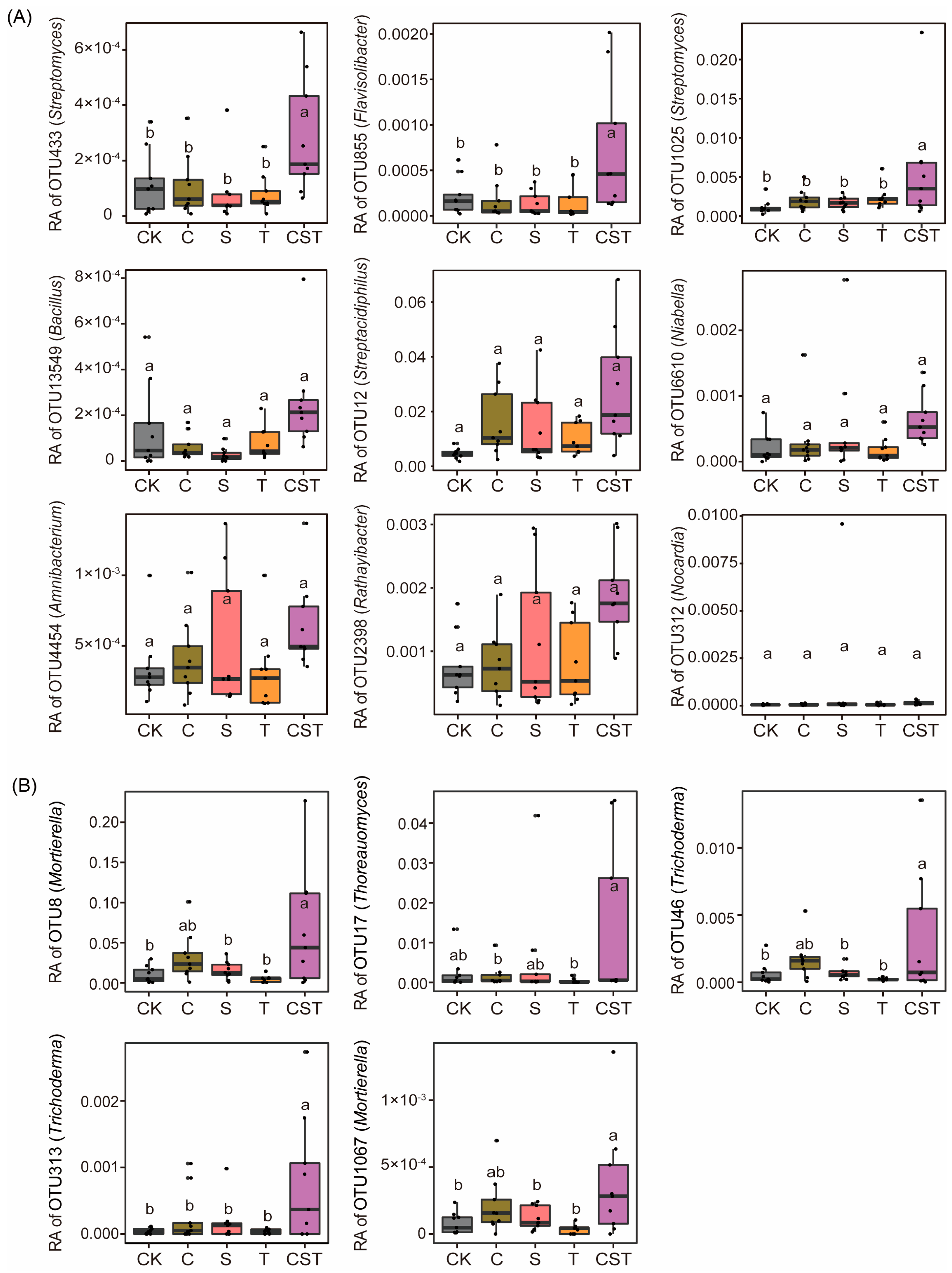

2.4. Effects of the Combined Application of Chitin, Straw, and Trichoderma on the Rhizosphere Microbial Taxonomic Composition and Its Relationships with Crop Yield and Pathogen Density

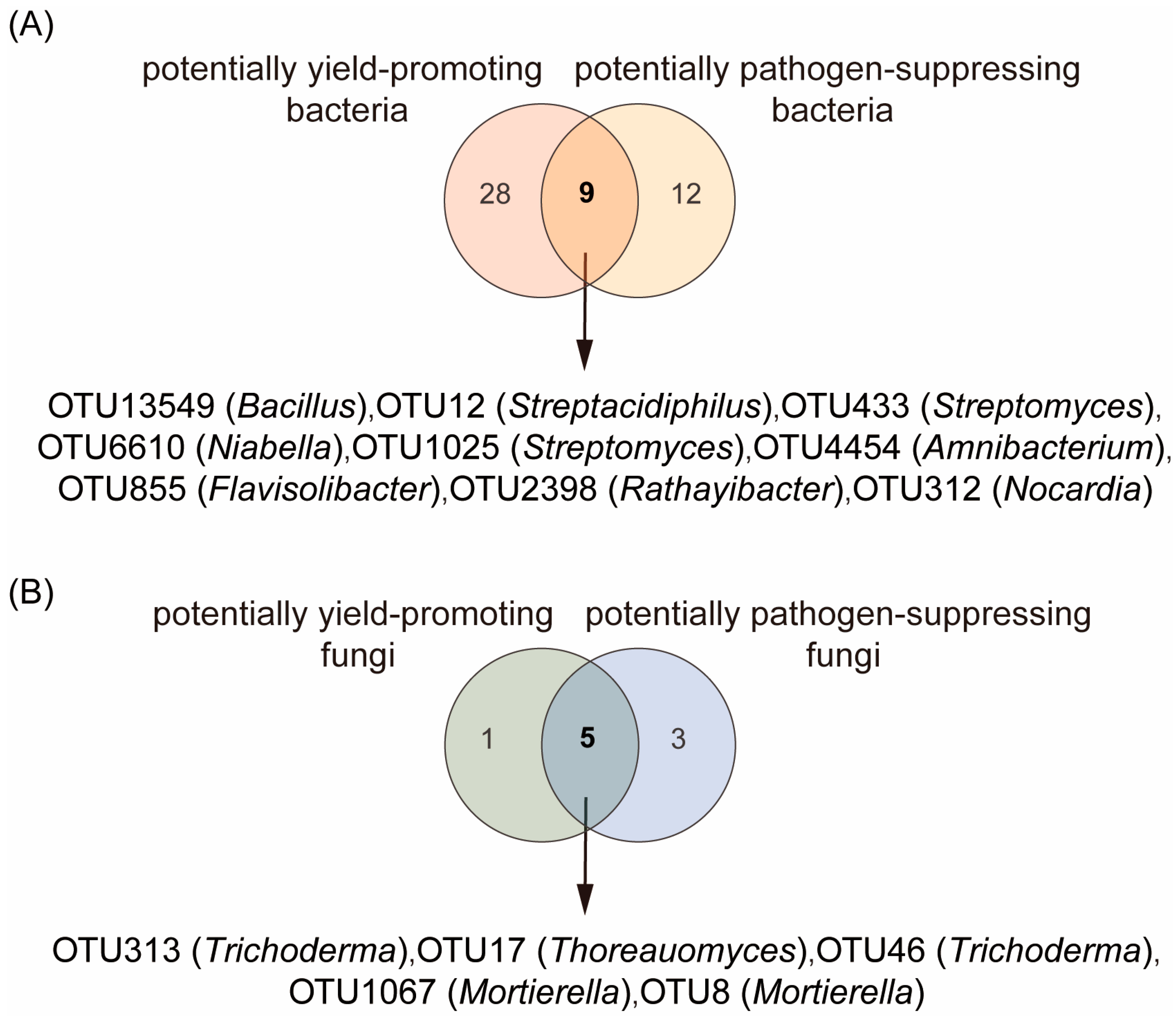

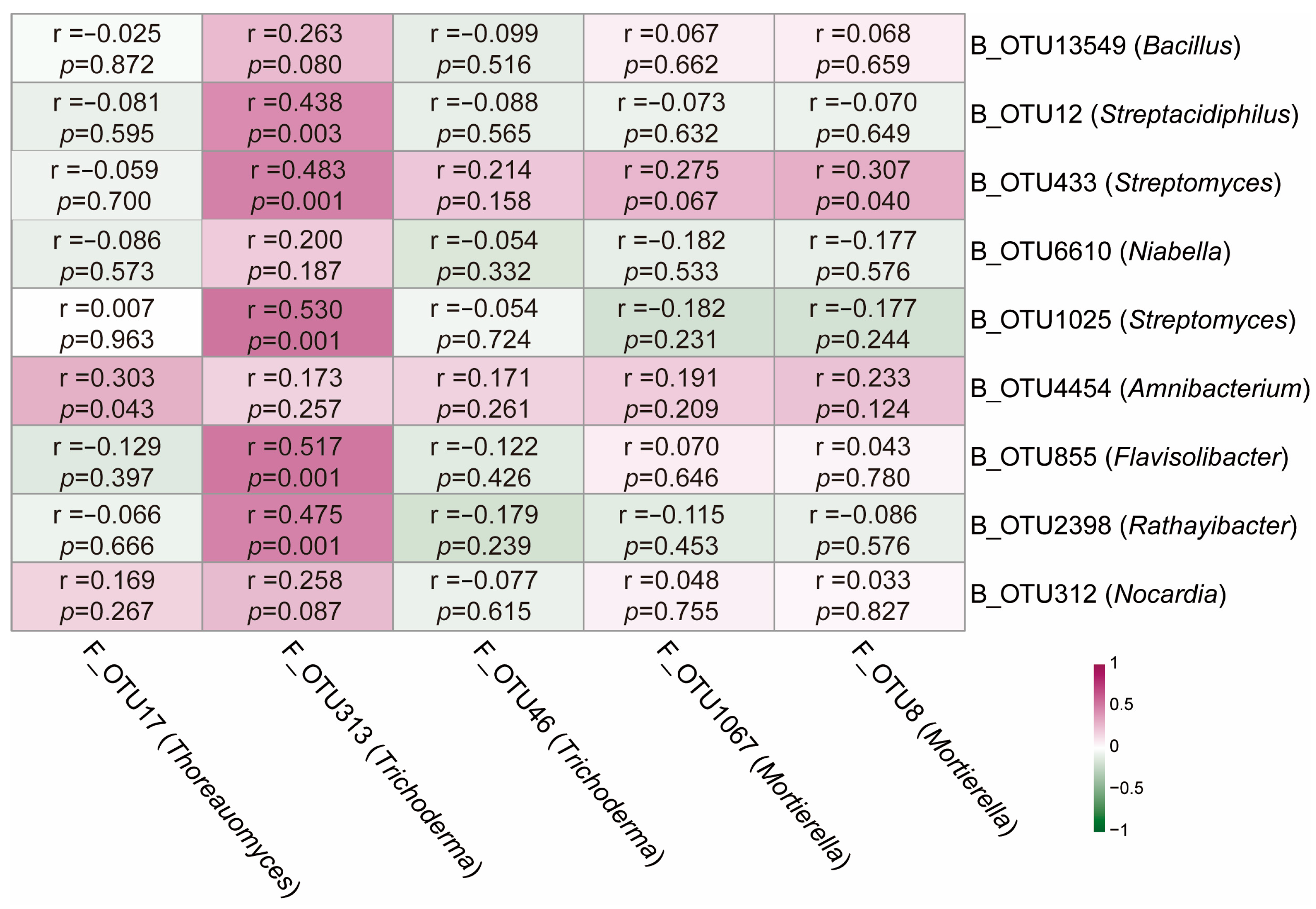

2.5. Relationships Between Core Rhizosphere Bacteria and Fungi with Combined Potentially Growth-Promoting and Pathogen-Suppressive Functions in Plants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

4.2. Cucumber Yield Measurement and Rhizosphere Soil Sample Collection

4.3. Soil Genomic DNA Extraction, Real-Time PCR, Illumina NovaSeq Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analyses

4.4. Network Analyses

4.5. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, M.; Sharma, P. Recent Advances in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Xian, Q.; Chen, X.; Xu, J. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Ethylene-Mediated Defense Responses to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cucumerinum Infection in Cucumis sativus L. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakalounakis, D.J.; Chalkias, J. Survival of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-cucumerinum in Soil. Crop Prot. 2004, 23, 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, K.; Tesoriero, L.; Daniel, R.; Guest, D. Sciarid and Shore Flies as Aerial Vectors of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum in Greenhouse Cucumbers. J. Appl. Entomol. 2014, 138, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, C.; Lal, R.; Yuan, P.; Liu, W.; Adhikari, A.; Bhandari, S.; Xia, Y. Plant Disease Suppressiveness Enhancement via Soil Health Management. Biology 2025, 14, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasir, M.; Hossain, A.; Pratap-Singh, A. Pesticide Degradation: Impacts on Soil Fertility and Nutrient Cycling. Environments 2025, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. Global Food Security and Sustainability Issues: The Road to 2030 from Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets to Food Systems Change. Foods 2024, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Wang, S.; Yan, X. Effects of Long-Term Straw Incorporation on the Net Global Warming Potential and the Net Economic Benefit in a Rice–Wheat Cropping System in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 197, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Tian, X.; Qiao, W.; Peng, C. Measuring Agricultural Total Factor Productivity in China: Pattern and Drivers over the Period of 1978–2016. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 64, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, R.-C.; Liu, W.-X.; Liu, W.-S.; Xue, Y.-H.; Sun, R.-H.; Wei, Y.-X.; Chen, Z.; Lal, R.; Dang, Y.P.; et al. Estimation of Crop Residue Production and Its Contribution to Carbon Neutrality in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 203, 107450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sanabria, A.; Kiesewetter, G.; Klimont, Z.; Schoepp, W.; Haberl, H. Potential for Future Reductions of Global GHG and Air Pollutants from Circular Waste Management Systems. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhila, D.S.; Ashwath, P.; Manjunatha, K.G.; Akshay, S.D.; Reddy Surasani, V.K.; Sofi, F.R.; Saba, K.; Dara, P.K.; Ozogul, Y.; Ozogul, F. Seafood Processing Waste as a Source of Functional Components: Extraction and Applications for Various Food and Non-Food Systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 145, 104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoll, V.; Bravo, P.; Pérez, M.N.; Pérez-Clavijo, M.; García-Castrillo, M.; Larrañaga, A.; Lizundia, E. Environmental Sustainability and Physicochemical Property Screening of Chitin and Chitin-Glucan from 22 Fungal Species. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 7869–7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendining, M.; Powlson, D.S. The Effect of Long-Term Applications of Inorganic Nitrogen Fertilizer on Soil Organic Nitrogen. In Advances in Soil Organic Matter Research; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Monte, E. Trichoderma: A Multipurpose, Plant-Beneficial Microorganism for Eco-Sustainable Agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J. Trichoderma and Its Role in Biological Control of Plant Fungal and Nematode Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1160551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Etesami, H.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma: A Multifunctional Agent in Plant Health and Microbiome Interactions. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil Microorganisms: Their Role in Enhancing Crop Nutrition and Health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musini, A.; Deepu, P.G.; Harikrishna, K.; Kumar, P.P.; Navyatha, S.; Harihara, J. Soil Microbial Community Dynamics and Plant Proliferation. In Soil Microbiome in Green Technology Sustainability; Aransiola, S.A., Atta, H.I., Maddela, N.R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 133–157. ISBN 978-3-031-71844-1. [Google Scholar]

- Walia, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Gupta, B.K.; Rana, N.; Sharma, A.; Verma, P. Biocontrol Potential of Trichoderma-Derived Chitinase: Optimization, Purification, and Antifungal Activity against Soilborne Pathogens of Apple. Front. Fungal Biol. 2025, 6, 1618728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappel, L.; Münsterkötter, M.; Sipos, G.; Escobar Rodriguez, C.; Gruber, S. Chitin and Chitosan Remodeling Defines Vegetative Development and Trichoderma Biocontrol. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lin, Z.; Que, Y.; Fallah, N.; Tayyab, M.; Li, S.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Abubakar, A.Y.; Zhang, H. Straw Retention Efficiently Improves Fungal Communities and Functions in the Fallow Ecosystem. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Cheruiyot, N.K.; Bui, X.-T.; Ngo, H.H. Composting and Its Application in Bioremediation of Organic Contaminants. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Chang, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Duan, C.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, T. Combined Application of Chemical and Organic Fertilizers Promoted Soil Carbon Sequestration and Bacterial Community Diversity in Dryland Wheat Fields. Land 2024, 13, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Begum, F.; Nguchu, B.A.; Claver, U.P.; Shaw, P. The Invisible Architects: Microbial Communities and Their Transformative Role in Soil Health and Global Climate Changes. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Jin, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, Z.; Luo, S.; Wu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Yu, J. Reduced Chemical Fertilizer Combined with Bio-Organic Fertilizer Affects the Soil Microbial Community and Yield and Quality of Lettuce. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 863325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Zuo, J.; Deng, J.; Yuan, L.; Gao, L.; Bai, W. Mixed Oligosaccharides-Induced Changes in Bacterial Assembly during Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Growth. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1195096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathor, P.; De Silva, C.; Lumactud, R.A.; Gorim, L.Y.; Quideau, S.A.; Thilakarathna, M.S. Humalite Shapes the Wheat Rhizosphere Soil Microbiome by Altering Microbial Community Structure, Diversity, and Network Stability. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 215, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J. Effects of Trichoderma Harzianum and Arthrobacter Ureafaciens on Control of Fusarium Crown Rot and Microbial Communities in Wheat Root-Zone Soil. Phytopathol. Res. 2025, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Miao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ma, L.; Guo, K.; Liu, D.; Ran, W.; Shen, Q. TgSWO from Trichoderma Guizhouense NJAU4742 Promotes Growth in Cucumber Plants by Modifying the Root Morphology and the Cell Wall Architecture. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.; Meng, L.; Ou, Y.; Shao, C.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, N.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Trichoderma-Amended Biofertilizer Stimulates Soil Resident Aspergillus Population for Joint Plant Growth Promotion. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Penton, C.R.; Xiong, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Reshaping the Rhizosphere Microbiome by Bio-Organic Amendment to Enhance Crop Yield in a Maize-Cabbage Rotation System. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A. Trophic Interactions of a Chitin-Degrading Microbiome of an Aerated Agricultural Soil. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Izadi, H.; Asadi, H.; Bemani, M. Chitin: A Comparison between Its Main Sources. Front. Mater. 2025, 12, 1537067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Dai, Y.; Cheng, X.; He, X.; Bei, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, K.; Tian, X.; et al. Straw Mulch Improves Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Cycle by Mediating Microbial Community Structure and Function in the Maize Field. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1217966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, E.A.; Martínez-Hidalgo, P.; Hirsch, A.M.; Veliz, E.A.; Martínez-Hidalgo, P.; Hirsch, A.M. Chitinase-Producing Bacteria and Their Role in Biocontrol. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Gu, S.; Peng, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Berendsen, R.L.; Yang, T.; Dong, C.; Wei, Z.; Xu, Y.; et al. Synergic Interactions between Trichoderma and the Soil Microbiomes Improve Plant Iron Availability and Growth. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielak, A.M.; Cretoiu, M.S.; Semenov, A.V.; Sørensen, S.J.; van Elsas, J.D. Bacterial Chitinolytic Communities Respond to Chitin and pH Alteration in Soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Xiong, W.; Hang, X.; Gao, Z.; Jiao, Z.; Liu, H.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, N.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Li, R.; et al. Protists as Main Indicators and Determinants of Plant Performance. Microbiome 2021, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hang, X. Formation Mechanism of High Yield Soil Microflora of Cucumber Based on Continous Application of Trichoderma Bio-Organic Fertilizer. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naïve Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of rRNA Se-quences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Zhou, P.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Trichoderma Guizhouense NJAU4742 Augments Morphophysiological Responses, Nutrient Availability and Photosynthetic Efficacy of Ornamental Ilex Verticillata. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Li, T.; Wu, H.; Xia, Y.; Huang, Q.; Liu, D.; Shen, Q. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Key Gene in Trichoderma Guizhouense NJAU4742 Enhancing Tomato Tolerance Under Saline Conditions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, W.; Hyde, E.R.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Ackermann, G.; Humphrey, G.; Parada, A.; Gilbert, J.A.; Jansson, J.K.; Caporaso, J.G.; Fuhrman, J.A.; et al. Improved Bacterial 16S rRNA Gene (V4 and V4-5) and Fungal Internal Transcribed Spacer Marker Gene Primers for Microbial Community Surveys. mSystems 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-High-Throughput Microbial Community Analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq Platforms. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.-X.; Li, X. USEARCH 12: Open-Source Software for Sequencing Analysis in Bioinformatics and Microbiome. iMeta 2024, 3, e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Guo, S.; Jousset, A.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, H.; Li, R.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Shen, Q. Bio-Fertilizer Application Induces Soil Suppressiveness against Fusarium Wilt Disease by Reshaping the Soil Microbiome. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 114, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W.; Revelle, M.W. Package ‘Psych’. Compr. R Arch. Netw. 2015, 337, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing Mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Hang, X.; Shao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Organic Amendments and Trichoderma Change the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Improve Cucumber Yield and Fusarium Suppression. Plants 2025, 14, 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233660

Wang Y, Hang X, Shao C, Zhang Z, Guo S, Li R, Shen Q. Organic Amendments and Trichoderma Change the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Improve Cucumber Yield and Fusarium Suppression. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233660

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuanming, Xinnan Hang, Cheng Shao, Zhiying Zhang, Sai Guo, Rong Li, and Qirong Shen. 2025. "Organic Amendments and Trichoderma Change the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Improve Cucumber Yield and Fusarium Suppression" Plants 14, no. 23: 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233660

APA StyleWang, Y., Hang, X., Shao, C., Zhang, Z., Guo, S., Li, R., & Shen, Q. (2025). Organic Amendments and Trichoderma Change the Rhizosphere Microbiome and Improve Cucumber Yield and Fusarium Suppression. Plants, 14(23), 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233660