Plasma Seed Priming Can Improve the Early Seedling Establishment and Antioxidant Activity of Water Convolvulus Microgreens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plasma Seed Priming Enhances Germination of Water Convolvulus

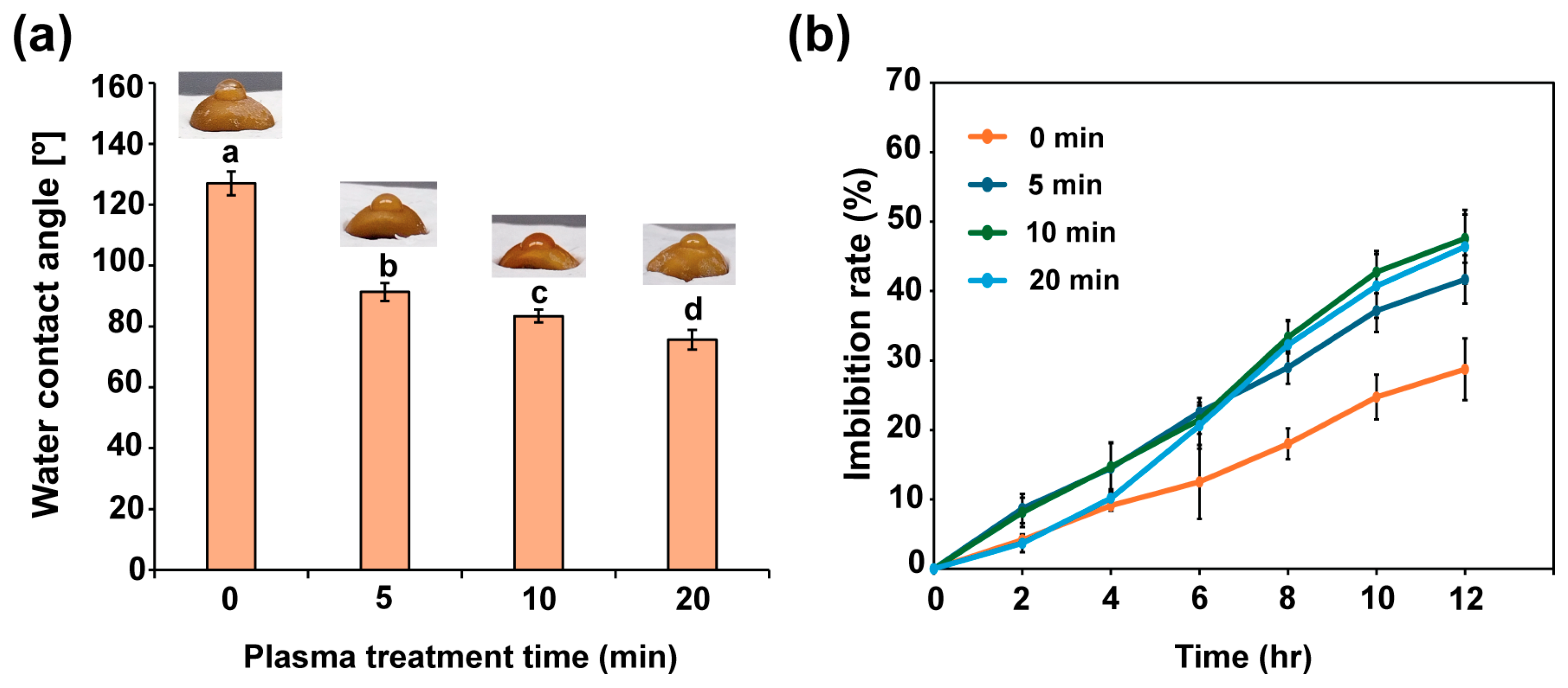

2.2. Plasma Seed Priming Increases Seed Surface Hydrophilicity

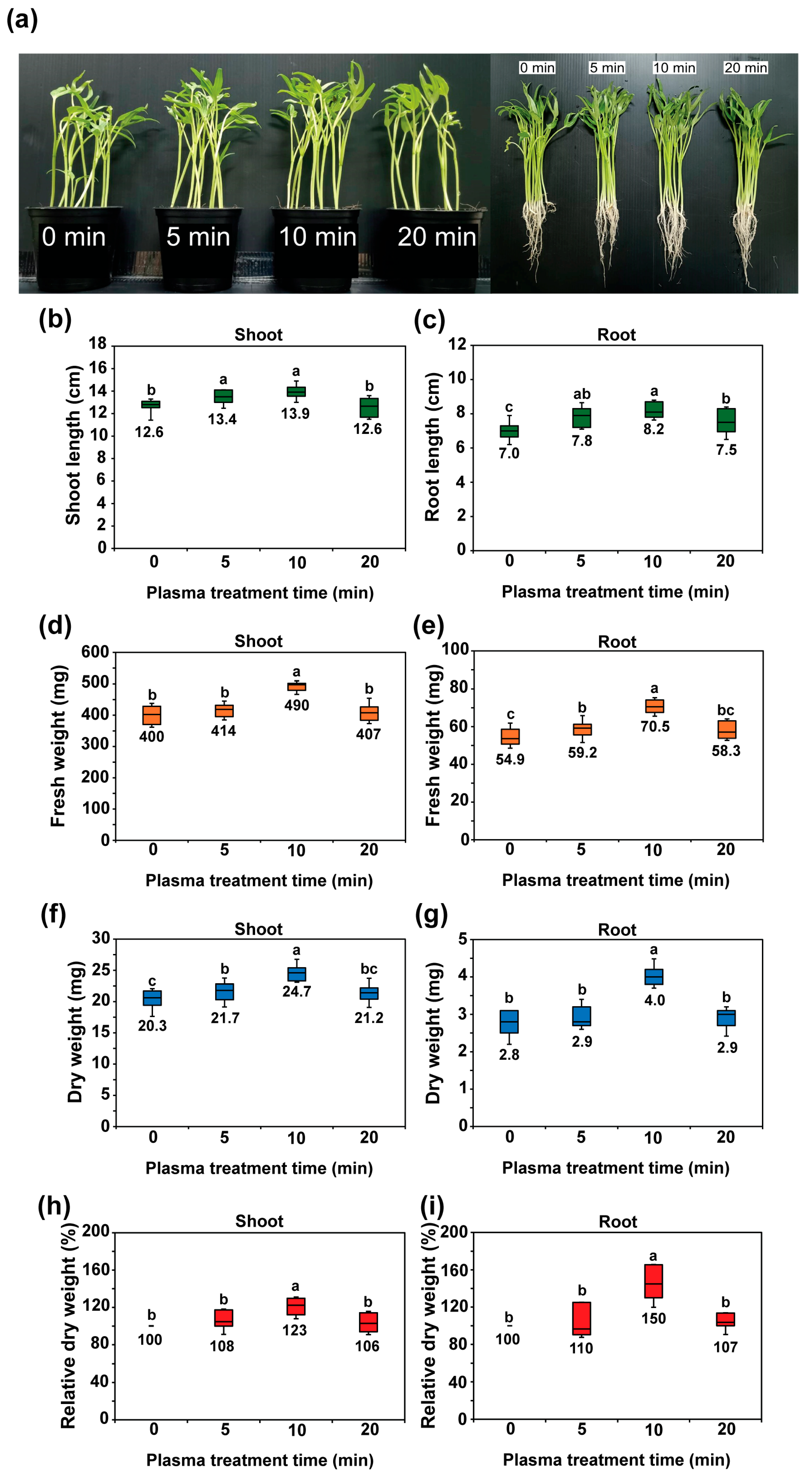

2.3. Plasma Seed Priming Improves Seedling Growth

2.4. Plasma Seed Priming Increases Chlorophyll and Protein Contents in Seedlings

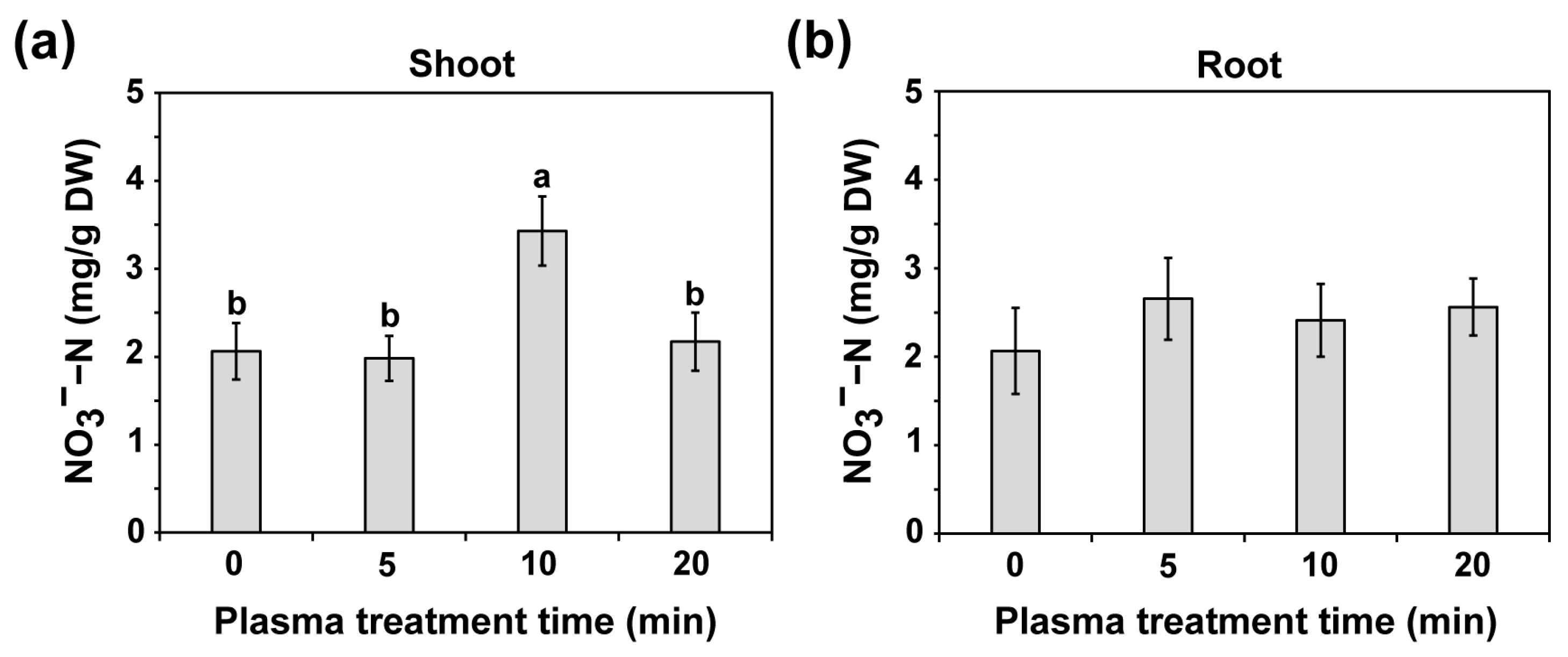

2.5. Plasma Seed Priming Enhances Nitrogen Uptake in Seedlings

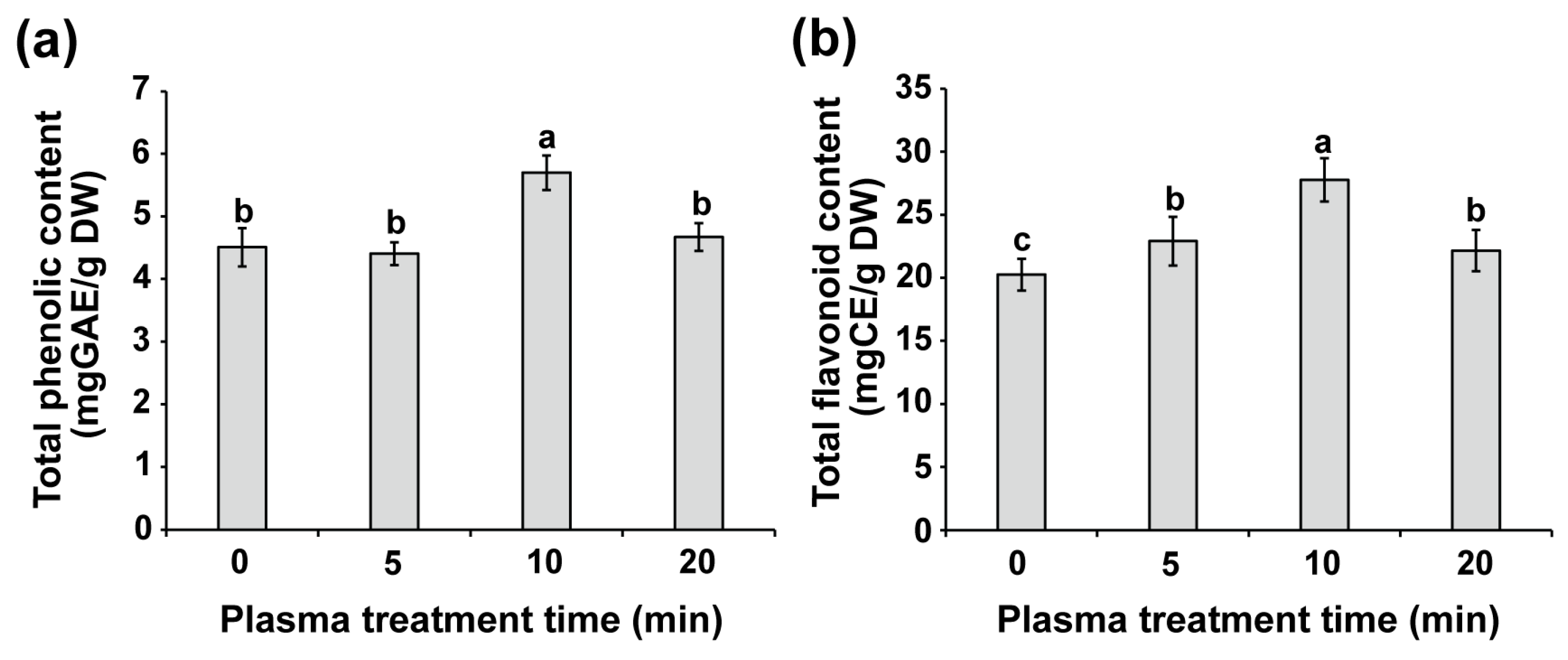

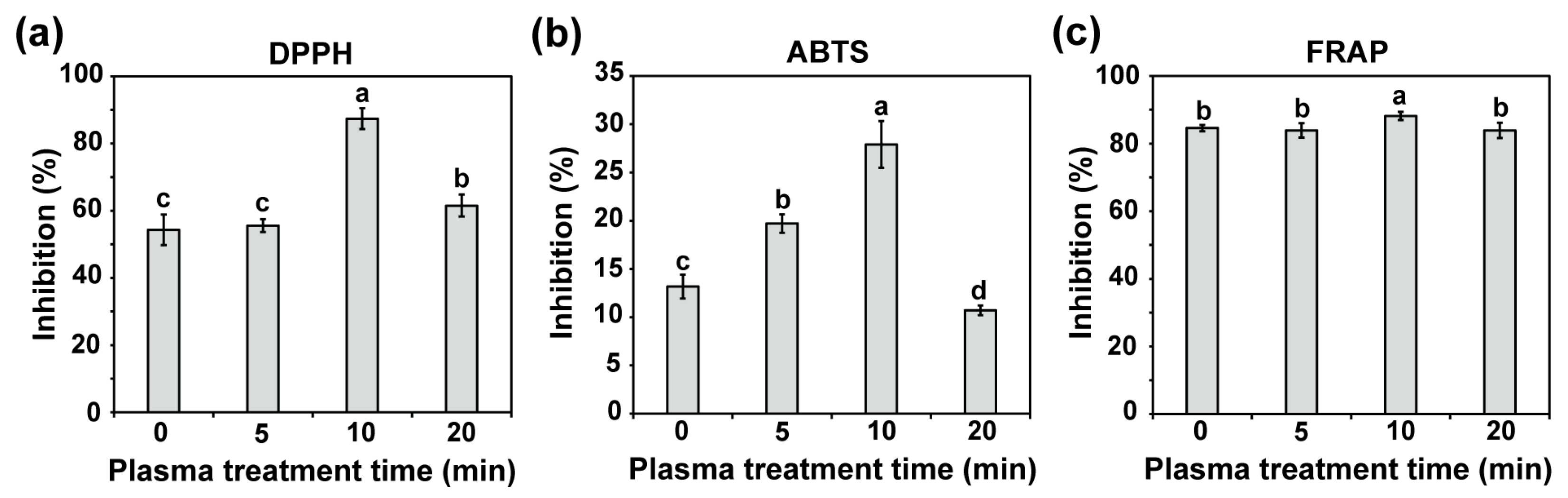

2.6. Plasma Seed Priming Enhances Phenolic, Flavonoid, and Antioxidant Levels in Seedlings

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma Source and Seed Treatment

4.2. Germination Efficiency and Seedling Growth Measurement

4.3. Measurement of Water Contact Angle and Water Imbibition on Plasma-Treated Seeds

4.4. Measurement of Chlorophyll Content

4.5. Analysis of Total Soluble Protein Content

4.6. Determination of Nitrogen Uptake (NO3−−N and NH4+)

4.7. Analysis of Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents

4.7.1. Plant Extraction

4.7.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Measurement

4.7.3. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) Measurement

4.8. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

4.8.1. DPPH Assay

4.8.2. ABTS Assay

4.8.3. FRAP Assay

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NTP | Non-thermal plasma |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| DBD | Dielectric barrier discharge |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| DW | Dry weight |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| Chl a | Chlorophyll a |

| Chl b | Chlorophyll b |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power assay |

References

- Bhaswant, M.; Shanmugam, D.K.; Miyazawa, T.; Abe, C.; Miyazawa, T. Microgreens—A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Molecules and Health Benefits. Molecules 2023, 28, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunjal, M.; Singh, J.; Kaur, J.; Kaur, S.; Nanda, V.; Sharma, A.; Rasane, P. Microgreens: Cultivation practices, bioactive potential, health benefits, and opportunities for its utilization as value-added food. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, T.; Mishra, G.P.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Deb Roy, P.; Devi, M.; Sahu, A.; Sarangi, S.K.; Mhatre, C.S.; Lyngdoh, Y.A.; Chandra, V.; et al. Microgreens: Functional Food for Nutrition and Dietary Diversification. Plants 2025, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, M.; Das, A.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Das, S.; Gangopadhyay, M.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica Forsk.) Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Vegetable Crops; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Chapter 5; pp. 183–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Li, C.; Zhou, X.; Xue, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, A.; Chen, S.; Mo, X.; Zhou, J. Microbial Diversity Analysis and Genome Sequencing Identify Xanthomonas perforans as the Pathogen of Bacterial Leaf Canker of Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatic). Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 752760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göthberg, A.; Greger, M.; Bengtsson, B.-E. Accumulation of heavy metals in water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) cultivated in the Bangkok region, Thailand. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21, 1934–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcussen, H.; Joergensen, K.; Holm, P.E.; Brocca, D.; Simmons, R.W.; Dalsgaard, A. Element contents and food safety of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica Forssk.) cultivated with wastewater in Hanoi, Vietnam. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 139, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwenyi, I.O.; Offor, C.E.; Ajah, D.A.; Nwankwo, O.C.; Ukaomah, J.I.; Aja, P.M. Chemical compositions of Ipomea aquatica (green kangkong). Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2011, 2, B-593–B-598. [Google Scholar]

- Saikia, K.; Dey, S.; Hazarika, S.N.; Handique, G.K.; Thakur, D.; Handique, A.K. Chemical and biochemical characterization of Ipomoea aquatica: Genoprotective potential and inhibitory mechanism of its phytochemicals against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1304903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokeng, S.D.; Rokeya, B.; Hannan, J.M.A.; Junaida, K.; Zitech, P.; Ali, L.; Ngounou, G.; Lontsi, D.; Kamtchouing, P. Inhibitory effect of Ipomoea aquatica extracts on glucose absorption using a perfused rat intestinal preparation. Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanjee, S.; Joardar, S.; Bhattacharjee, N.; Dua, T.K.; Das, S.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Edible leaf extract of Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. (Convolvulaceae) attenuates doxorubicin-induced liver injury via inhibiting oxidative impairment, MAPK activation and intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 105, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasikala, M.; Mohan, S.; Swarnakumari, S.; Nagarajan, A. Isolation and in vivo evaluation of anti-breast cancer activity of resin glycoside merremoside from Ipomoea aquatica Forsskal in overcoming multi-drug resistance. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, R.K.; Biswas, A.K.; Iqbal, M.A.; Reza, M.M. Seed Germination and Seedling Development in Vegetable Crops. In Growth Regulation and Quality Improvement of Vegetable Crops: Physiological and Molecular Features; Ahammed, G.J., Zhou, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Waqas, M.; Korres, N.; Khan, D.; Nizami, A.-S.; Deeba, F.; Ali, I.; Hussain, H. Advances in the Concept and Methods of Seed Priming. In Priming and Pretreatment of Seeds and Seedlings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

- Devika, O.S.; Singh, S.; Sarkar, D.; Barnwal, P.; Suman, J.; Rakshit, A. Seed Priming: A Potential Supplement in Integrated Resource Management Under Fragile Intensive Ecosystems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 654001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulikienė, S.; Benesevičius, D.; Benesevičienė, K.; Ūksas, T. Review—Seed Treatment: Importance, Application, Impact, and Opportunities for Increasing Sustainability. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mravlje, J.; Regvar, M.; Vogel-Mikuš, K. Development of Cold Plasma Technologies for Surface Decontamination of Seed Fungal Pathogens: Present Status and Perspectives. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Veerana, M.; Choi, E.-H.; Park, G. Effects of Pre-Treatment Using Plasma on the Antibacterial Activity of Mushroom Surfaces. Foods 2021, 10, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskow, A.; Howling, A.; Furno, I. Mechanisms of Plasma-Seed Treatments as a Potential Seed Processing Technology. Front. Phys. 2021, 9, 617345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sera, B. Non-thermal Plasma Technology: A Sustainable Solution for Agriculture. In Advances in Seed Quality Evaluation and Improvement; Roy, B., Shukla, G., Dunna, V., Sharma, P., Shukla, P.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, P.; Sehgal, H.; Joshi, M.; Arora, G.; Simek, M.; Lamba, R.P.; Maurya, S.; Pal, U.N. Advances in using non-thermal plasmas for healthier crop production: Toward pesticide and chemical fertilizer-free agriculture. Planta 2025, 261, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, G.; Cela, F.; Trivellini, A.; Gambineri, F.; Cursi, L.; Cecchi, A.; Pardossi, A.; Incrocci, L. Effects of Nonthermal Plasma (NTP) on the Growth and Quality of Baby Leaf Lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. Acephala alef.) Cultivated in an Indoor Hydroponic Growing System. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerana, M.; Ketya, W.; Choi, E.-H.; Park, G. Non-thermal plasma enhances growth and salinity tolerance of bok choy (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) in hydroponic culture. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodini, M.; Traversari, S.; Cacini, S.; Gonfiotti, I.; Lenzi, A.; Massa, D. The effect of plasma-treated nutrient solution on yield, pigments, and mineral content of rocket [Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC.] grown under different nitrogen fertilization levels. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1511335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, S.; Khan, R.; Rana, J.N.; Javed, R.; Iqbal, M.; Choi, E.H.; Han, I. Review on the Biomedical and Environmental Applications of Nonthermal Plasma. Catalysts 2023, 13, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Adhikari, M.; Park, G. The Effects of Plasma on Plant Growth, Development, and Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holc, M.; Mozetič, M.; Recek, N.; Primc, G.; Vesel, A.; Zaplotnik, R.; Gselman, P. Wettability Increase in Plasma-Treated Agricultural Seeds and Its Relation to Germination Improvement. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Song, J.S.; Woo, S.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Song, S.-Y.; Seo, W.D.; Son, Y.-J.; et al. Cold Plasma Treatment Increases Bioactive Metabolites in Oat (Avena sativa L.) Sprouts and Enhances In Vitro Osteogenic Activity of their Extracts. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2023, 78, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerana, M.; Mumtaz, S.; Rana, J.N.; Javed, R.; Panngom, K.; Ahmed, B.; Akter, K.; Choi, E.H. Recent Advances in Non-Thermal Plasma for Seed Germination, Plant Growth, and Secondary Metabolite Synthesis: A Promising Frontier for Sustainable Agriculture. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2024, 44, 2263–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungmunnithum, D.; Thongboonyou, A.; Pholboon, A.; Yangsabai, A. Flavonoids and Other Phenolic Compounds from Medicinal Plants for Pharmaceutical and Medical Aspects: An Overview. Medicines 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, S.; Cao, W.; Fan, D.; Duan, Z.; Xia, Z. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis of cold plasma promoting biosynthesis of active substances in broccoli sprouts. Phytochem. Anal. 2023, 34, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luang-In, V.; Saengha, W.; Karirat, T.; Buranrat, B.; Matra, K.; Deeseenthum, S.; Katisart, T. Effect of cold plasma and elicitors on bioactive contents, antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of Thai rat-tailed radish microgreens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 1685–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, L.; Jiafeng, J.; Jiangang, L.; Minchong, S.; Xin, H.; Hanliang, S.; Yuanhua, D. Effects of cold plasma treatment on seed germination and seedling growth of soybean. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiafeng, J.; Xin, H.; Ling, L.; Jiangang, L.; Hanliang, S.; Qilai, X.; Renhong, Y.; Yuanhua, D. Effect of Cold Plasma Treatment on Seed Germination and Growth of Wheat. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2014, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Sohan, M.S.R.; Sajib, S.A.; Hossain, M.F.; Miah, M.; Maruf, M.M.H.; Khalid-Bin-Ferdaus, K.M.; Kabir, A.H.; Talukder, M.R.; Rashid, M.M.; et al. The Effect of Low-Pressure Dielectric Barrier Discharge (LPDBD) Plasma in Boosting Germination, Growth, and Nutritional Properties in Wheat. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2022, 42, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Dong, Y. Effect of cold plasma treatment on seedling growth and nutrient absorption of tomato. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2018, 20, 044007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.; Sajib, S.A.; Roy, N.C.; Rashid, M.M.; Reza, M.A.; Hasan, M.M.; Talukder, M.R. Effects of DBD air plasma treatment on the enhancement of black gram (Vigna mungo L.) seed germination and growth. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 681, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.F.; Sohan, M.S.R.; Hasan, M.; Miah, M.M.; Sajib, S.A.; Karmakar, S.; Khalid-Bin-Ferdaus, K.M.; Kabir, A.H.; Rashid, M.M.; Talukder, M.R.; et al. Enhancement of Seed Germination Rate and Growth of Maize (Zea mays L.) Through LPDBD Ar/Air Plasma. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1778–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randeniya, L.K.; de Groot, G.J.J.B. Non-Thermal Plasma Treatment of Agricultural Seeds for Stimulation of Germination, Removal of Surface Contamination and Other Benefits: A Review. Plasma Process. Polym. 2015, 12, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhu, S.; Thirumdas, R.; Deshmukh, R.R.; Annapure, U.S. Influence of cold plasma on the enzymatic activity in germinating mung beans (Vigna radiate). LWT 2017, 78, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatama, R.A.; Pervitasari, A.N.; Park, S.; Park, S.J.; Lee, Y.K. Current Advancements in the Molecular Mechanism of Plasma Treatment for Seed Germination and Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglia, G.D. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) signalling in seed dormancy release, perception of environmental cues, and heat stress response. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 103, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C. The signalling role of ROS in the regulation of seed germination and dormancy. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 3019–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajer, M.H.; Khademi, A.; Rahmani, M.; Monfaredi, M.; Hamidi, A.; Mirjalili, M.H.; Ghomi, H. Optimizing beet seed germination via dielectric barrier discharge plasma parameters. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash Guragain, R.; Bahadur Baniya, H.; Prakash Guragain, D.; Prasad Subedi, D. Exploring the effects of non-thermal plasma pre-treatment on coriander (Coriander sativum L.) seed germination efficiency. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalal, A.; Oliveira Junior, J.C.D.; Ribeiro, J.S.; Fernandes, G.C.; Mariano, G.G.; Trindade, V.D.R.; Reis, A.R.D. Hormesis in plants: Physiological and biochemical responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, B.; Adhikari, M.; Ghimire, B.; Adhikari, B.C.; Park, G.; Choi, E.H. Cold plasma seed priming modulates growth, redox homeostasis and stress response by inducing reactive species in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 156, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paatre Shashikanthalu, S.; Ramireddy, L.; Radhakrishnan, M. Stimulation of the germination and seedling growth of Cuminum cyminum L. seeds by cold plasma. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2020, 18, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guragain, R.; Baniya, H.; Dhungana, S.; Kuwar Chhetri, G.; Sedhai, B.; Basnet, N.; Shakya, A.; Pandey, B.; Pradhan, S.; Joshi, U.; et al. Effect of plasma treatment on the seed germination and seedling growth of radish (Raphanus sativus). Plasma Sci. Technol. 2022, 24, 015502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orman-Ligeza, B.; Parizot, B.; de Rycke, R.; Fernandez, A.; Himschoot, E.; Van Breusegem, F.; Bennett, M.J.; Périlleux, C.; Beeckman, T.; Draye, X. RBOH-mediated ROS production facilitates lateral root emergence in Arabidopsis. Development 2016, 143, 3328–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova, M.; Svubova, R.; Kyzek, S.; Medvecka, V.; Slovakova, L.; Sevcovicova, A.; Galova, E. The Effects of Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma on Germination Parameters, Enzyme Activities and Induction of DNA Damage in Barley. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, M.; Modarres-Sanavy, S.A.M.; Zare, R.; Ghomi, H. Amelioration of Photosynthesis and Quality of Wheat under Non-thermal Radio Frequency Plasma Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Shen, M.; Hou, J.; Shao, H.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, J. Improving Seed Germination and Peanut Yields by Cold Plasma Treatment. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2016, 18, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezowski, P.; Richter, A.S.; Grimm, B. Regulation and function of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in plants and algae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Al Azzawi, T.N.; Saqib, S.; Ullah, F.; Ayaz, A.; Zaman, W. The Key Roles of ROS and RNS as a Signaling Molecule in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.-C.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.-Y.; Song, C.-P. Reactive oxygen species: Multidimensional regulators of plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasooli, Z.; Barzin, G.; Mahabadi, T.D.; Entezari, M. Stimulating effects of cold plasma seed priming on germination and seedling growth of cumin plant. South Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 142, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, F.; Markgren, J.; Hedenqvist, M.; Johansson, E. Modeling to Understand Plant Protein Structure-Function Relationships—Implications for Seed Storage Proteins. Molecules 2020, 25, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Sarkar, M.; Khan, A.; Biswas, M.; Masi, A.; Rakwal, R.; Agrawal, G.K.; Srivastava, A.; Sarkar, A. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) in plants—Maintenance of structural individuality and functional blend. Adv. Redox Res. 2022, 5, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Jiangang, L.; Minchong, S.; Chunlei, Z.; Yuanhua, D. Cold plasma treatment enhances oilseed rape seed germination under drought stress. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zheng, N. Molecular Mechanism Underlying the Plant NRT1.1 Dual-Affinity Nitrate Transporter. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Huang, D. The Utilization and Roles of Nitrogen in Plants. Forests 2024, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Tian, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; Li, S. The crosstalk between nitrate signaling and other signaling molecules in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1546011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Llamas, A.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. Role of Nitrate Reductase in NO Production in Photosynthetic Eukaryotes. Plants 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, M.; Janicka, M.; Kabała, K. 4-Nitrate reductase dependent synthesis of NO in plants. In Nitric Oxide in Plant Biology; Pratap Singh, V., Singh, S., Tripathi, D.K., Romero-Puertas, M.C., Sandalio, L.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Shahzad, B.; Rehman, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Landi, M.; Zheng, B. Response of Phenylpropanoid Pathway and the Role of Polyphenols in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Molecules 2019, 24, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Anmol, A.; Kumar, S.; Wani, A.W.; Bakshi, M.; Dhiman, Z. Exploring phenolic compounds as natural stress alleviators in plants—A comprehensive review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, J.R.; Mhatre, K.J.; Yadav, K.; Yadav, L.S.; Srivastava, S.; Nikalje, G.C. Flavonoids in plant-environment interactions and stress responses. Discov. Plants 2024, 1, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranbakhsh, A.; Ghoranneviss, M.; Oraghi Ardebili, Z.; Oraghi Ardebili, N.; Hesami Tackallou, S.; Nikmaram, H. Non-thermal plasma modified growth and physiology in Triticum aestivum via generated signaling molecules and UV radiation. Biol. Plant. 2017, 61, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgedaite-Seziene, V.; Lucinskaite, I.; Mildaziene, V.; Ivankov, A.; Koga, K.; Shiratani, M.; Lauzike, K.; Baliuckas, V. Changes in Content of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity Induced in Needles of Different Half-Sib Families of Norway Spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst) by Seed Treatment with Cold Plasma. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, M.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Flavonoids: Antioxidant Powerhouses and Their Role in Nanomedicine. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.J.; Duan, M.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, P.; Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Shen, Q.; Ji, P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Signaling, and Scavenging During Abiotic Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D. Plant Foods, Antioxidant Biomarkers, and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality: A Review of the Evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S404–S421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Admasu, K.A.; Choi, E.H. Selective productions of reactive species in dielectric barrier discharge by controlling dual duty cycle. Plasma Process. Polym. 2024, 21, e2400098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Dong, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, S.; Bai, X. Effects of foliar application of salicylic acid and nitric oxide in alleviating iron deficiency induced chlorosis of Arachis hypogaea L. Bot. Stud. 2014, 55, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra, O. Derivative Spectrophotometric Determination of Nitrate in Plant Tissue. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.A.; Woollard, D.C.; Irving, D.E.; Borst, W.M. Physiological changes in asparagus spear tips after harvest. Physiol. Plant. 1990, 80, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, D.T.; Akele, M.L.; Melese, A.T. Analysis of total phenolic contents, flavonoids, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Croton macrostachyus root extracts. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molole, G.J.; Gure, A.; Abdissa, N. Determination of total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Commiphora mollis (Oliv.) Engl. resin. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, N.; Santiago, A.; Alías, J.C. Quantification of the Antioxidant Activity of Plant Extracts: Analysis of Sensitivity and Hierarchization Based on the Method Used. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minarti, M.; Ariani, N.; Megawati, M.; Hidayat, A.; Hendra, M.; Primahana, G.; Darmawan, A. Potential Antioxidant Activity Methods DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, Total Phenol and Total Flavonoid Levels of Macaranga hypoleuca (Reichb. f. & Zoll.) Leaves Extract and Fractions. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 503, 07005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veerana, M.; Poochim, B.; Intharasuwan, P.; Saphanthong, P.; Lim, J.-S.; Choi, E.-H.; Park, G. Plasma Seed Priming Can Improve the Early Seedling Establishment and Antioxidant Activity of Water Convolvulus Microgreens. Plants 2025, 14, 3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233648

Veerana M, Poochim B, Intharasuwan P, Saphanthong P, Lim J-S, Choi E-H, Park G. Plasma Seed Priming Can Improve the Early Seedling Establishment and Antioxidant Activity of Water Convolvulus Microgreens. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233648

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeerana, Mayura, Burapa Poochim, Praepun Intharasuwan, Phatlada Saphanthong, Jun-Sup Lim, Eun-Ha Choi, and Gyungsoon Park. 2025. "Plasma Seed Priming Can Improve the Early Seedling Establishment and Antioxidant Activity of Water Convolvulus Microgreens" Plants 14, no. 23: 3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233648

APA StyleVeerana, M., Poochim, B., Intharasuwan, P., Saphanthong, P., Lim, J.-S., Choi, E.-H., & Park, G. (2025). Plasma Seed Priming Can Improve the Early Seedling Establishment and Antioxidant Activity of Water Convolvulus Microgreens. Plants, 14(23), 3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233648