Microminutinin, a Fused Bis-Furan Coumarin from Murraya euchrestifolia, Exhibits Strong Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity by Disrupting Cell Membranes and Walls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antifungal Coumarin Guided Isolation

2.1.1. The Antifungal Activity of M. euchrestifolia Methanol Extract (ME)

2.1.2. Antifungal Fraction Screening of ME

2.1.3. Isolation of Antifungal Coumarin

2.2. Structural Identification of 1

2.3. The Antifungal Activity of Microminutinin In Vitro

2.4. The Suppressive Effect of Microminutinin on the TGB Pathogenicity In Vivo

2.5. Effects of Microminutinin on the Mycelial Morphology of P. theae

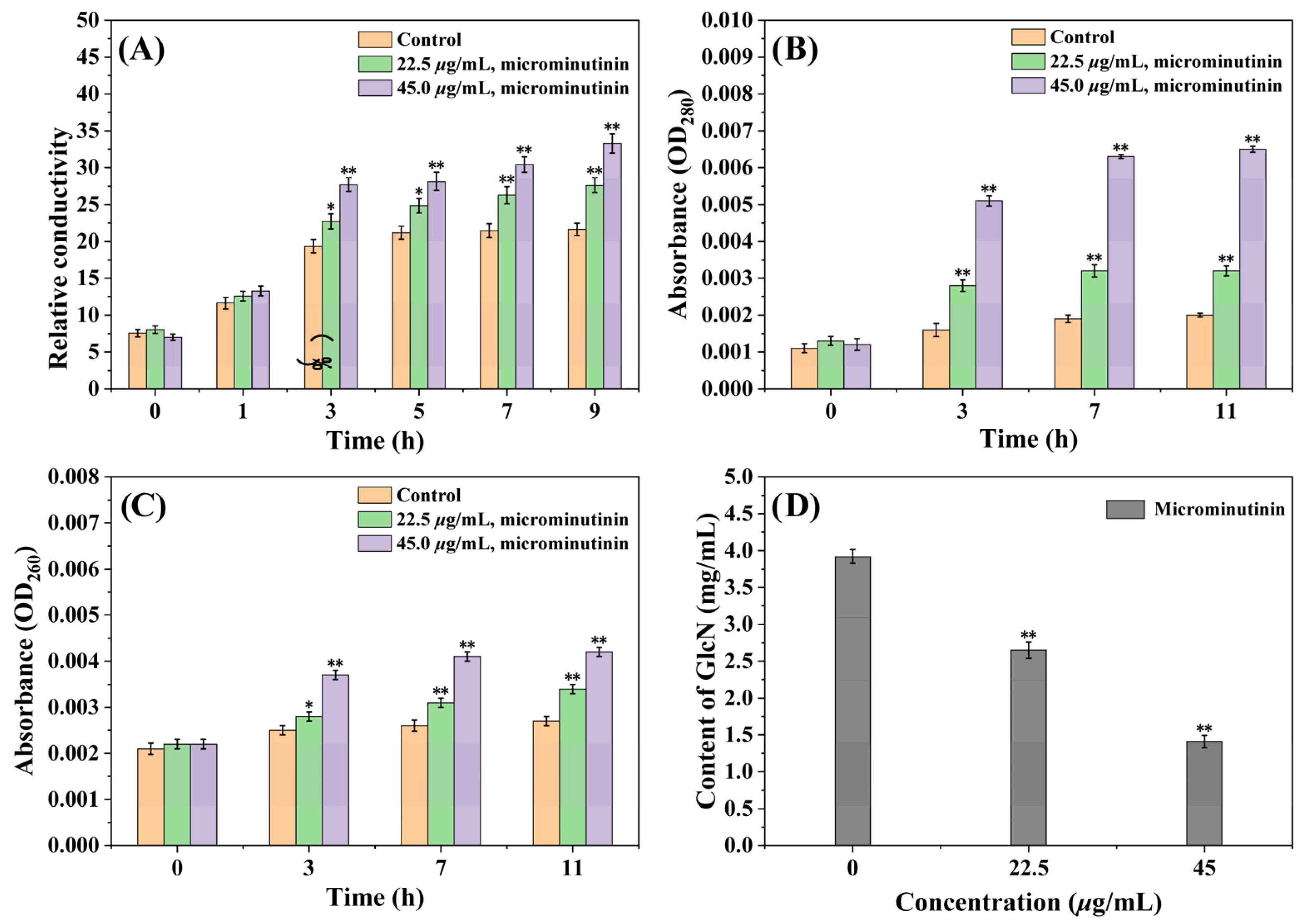

2.6. The Impact of Microminutinin on the Cell Membrane

2.6.1. The Impact of Microminutinin on Cell Membrane Integrity

2.6.2. Effects of Microminutinin on the Cell Membrane Permeability (CMP)

2.7. Effects of Microminutinin on the Cell Wall

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant, Pathogens and Chemicals

4.2. Antifungal Coumarin Guided Isolation

4.3. Determination of Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity In Vitro

4.4. The Suppressive Effect of 1 on the Pathogenicity of TGB

4.5. The Influence of 1 on Mycelial Morphology

4.5.1. OM

4.5.2. SEM

4.6. Assay of Plasma Membrane Integrity of P. theae

4.7. Cell Wall Integrity Measurement

4.8. Determination of Electrolyte Leakage

4.9. Cytoplasmic Leakage Assay

4.10. Determination of Chitin Content

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dayan, F.E.; Cantrell, C.L.; Duke, S.O. Natural products in crop protection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 4022–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, C.L.; Dayan, F.E.; Duke, S.O. Natural products as sources for new pesticides. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.J.; Kong, D.; He, S.; Chen, J.Z.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Z.Q.; Feng, J.T.; Yan, H. Phenanthrene derivatives from Asarum heterotropoides showed excellent antibacterial activity against phytopathogenic bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 14520–14529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.L. Research and development progress of pyrethroid Insecticides. Chem. Reagt. 2024, 46, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.J. Advance on the research and development of China-innovated neonicotinoid insecticides. World Pestic. 2023, 45, 1–12+55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgaud, F.; Hehn, A.; Larbat, R.; Doerper, S.; Gontier, E.; Kellner, S.; Matern, U. Biosynthesis of coumarins in plants: A major pathway still to be unravelled for cytochrome P450 enzymes. Phytochem. Rev. 2006, 5, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limones-Mendez, M.; Dugrand-Judek, A.; Villard, C.; Coqueret, V.; Froelicher, Y.; Bourgaud, F.; Olry, A.; Hehn, A. Convergent evolution leading to the appearance of furanocoumarins in citrus plants. Plant Sci. 2020, 292, 110392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robe, K.; Izquierdo, E.; Vignols, F.; Rouached, H.; Dubos, C. The coumarins: Secondary metabolites playing a primary role in plant nutrition and health. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barot, K.P.; Jain, S.V.; Kremer, L.; Singh, S.; Ghate, M.D. Recent advances and therapeutic journey of coumarins: Current status and perspectives. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 2771–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringlis, I.A.; Jonge, R.; Pieterse, C.M.J. The age of coumarins in plantmicrobe interactions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1405–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yao, X.Y.; Ding, W. The advances on antibacterial activity of coumarins. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2018, 30, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, K.; Shimizu, B.I.; Mizutani, M.; Watanabe, K.; Sakata, K. Accumulation of coumarins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.C.; Tang, H.; Wei, X.F.; He, Y.D.; Hu, S.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Xu, D.Q.; Qiao, F.; Xue, J.Y.; Zhao, Y.C. The gradual establishment of complex coumarin biosynthetic pathway in Apiaceae. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wei, Z.L.; Li, S.L.; Xiao, R.; Xu, Q.Q.; Ran, Y.; Ding, W. Plant secondary metabolite, daphnetin reduces extracellular polysaccharides production and virulence factors of Ralstonia solanacearum. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 179, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.Q.; Ma, J.H.; Hettenhausen, C.; Cao, G.Y.; Sun, G.L.; Wu, J.Q.; Wu, J.S. Scopoletin is a phytoalexin against Alternaria alternata in wild tobacco dependent on jasmonate signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4305–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, P.; Schneider, B.; Svatoš, A.; Oldham, N.J.; Hahlbrock, K. Structural complexity, differential response to infection, and tissue specificity of indolic and phenylpropanoid secondary metabolism in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Cao, N.K.; Tu, P.F.; Jiang, Y. Chemical constituents from Murraya euchrestifolia. Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2017, 42, 1916–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.D.; Pu, Q.L.; Yang, G.Z. The chemical components of the essential oil from Murraya euchrestifolia Hayata. Acta Pharm. Sin. 1983, 18, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.S.; Wang, M.L.; Wu, P.L.; Ito, C.; Furukawa, H. Carbazole alkaloids from the leaves of Murraya euchrestifolia. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 1433–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.S.; Wang, M.L.; Wu, P.L.; Jong, T.T. Two carbazole alkaloids from leaves of Murraya euchrestifolia. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1817–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, C.; Okahana, N.; Wu, T.S.; Furukawa, H. New carbazole alkaloids from Murraya euchrestifolia. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 40, 2377–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Fu, X.X.; Chen, J.G.; Yang, Y.L.; Wu, W.X.; Xiao, S.L.; Huang, Y.J.; Peng, W.W. Antifungal alkaloids from the branch-leaves of Clausena lansium Lour. Skeels (Rutaceae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 2675–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Ismail, H.B.M.; Sukari, A.; Waterman, P.G. New coumarin and dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives from two malaysian populations of Micromelum minutum. Phytochemistry 1994, 31, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperdick, C.; Phuong, N.M.; Sung, T.V.; Schmidt, J.; Adam, G. Coumarins and dihydrocinnamic acid derivatives from Micromelum falcatum. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.M.; He, W.H.; Yin, H.; Li, Q.X.; Liu, Q. Two New Coumarins from Micromelum falcatum with Cytotoxicity and Brine Shrimp Larvae Toxicity. Molecules 2012, 17, 6944–6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakornwong, W.; Kanokmedhakul, K.; Kanokmedhakul, S. Chemical constituents from the roots of Leea thorelii Gagnep. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1015–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walasek, M.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Malm, A.; Krystyna, S.W. Bioactivity-guided isolation of antimicrobial coumarins from Heracleum mantegazzianum Sommier & Levier (Apiaceae) fruits by high-performance counter-current chromatography. Food Chem. 2015, 186, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad-Bzeouich, I.; Mustapha, N.; Chaabane, F.; Ghedira, Z.; Chekir-Ghedira, L. Oligomerization of esculin improves its antibacterial activity and modulates antibiotic resistance. J. Antibiot. 2014, 68, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Khan, R.; Bhat, K.A.; Raja, A.F.; Shawl, A.S.; Alam, M.S. Isolation, characterisation and antibacterial activity studies of coumarins from Rhododendron lepidotum Wall. ex, G. Don, Ericaceae. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2010, 20, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, O.; Kolodziejet, H. Antibacterial activity of simple coumarins: Structural requirements for biological activity. Z. Naturforschung C 1999, 54, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, K.; Mizutani, M.; Kawamura, N.; Yamamoto, R.; Tamai, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sakata, K.; Shimizu, B. Scopoletin is biosynthesized via ortho-hydroxylation of feruloyl CoA by a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008, 55, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, T.; Ramachandran, V.N.; Smyth, W.F. A study of the antimicrobial activity of selected naturally occurring and synthetic coumarins. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2009, 33, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, C.L.; Avila, J.G.; Martínez, A.; Serrato, B.; Salgado-Garciglia, R. Antifungal and antibacterial activities of Mexican tarragon (Tagetes lucida). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3521–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Long, Y.; Yin, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Mo, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, B. Antifungal activity and mechanism of tetramycin against Alternaria alternata, the soft rot causing fungi in kiwifruit. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 192, 105409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.F.; Yang, C.J.; Shang, X.F.; Zhao, Z.M.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhou, R.; Liu, H.; Wu, T.L.; Zhao, W.B.; Wang, Y.L.; et al. Bioassay-guided isolation of two antifungal compounds from Magnolia officinalis, and the mechanism of action of honokiol. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 170, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.E.; Sánchez-Fuentes, R.; Rangel-Sánchez, H.; Hernández-Orteg, S.; López-Cortés, J.G.; Macías-Rubalcava, M.L. Antifungal and antioomycete activities and modes of action of isobenzofuranones isolated from the endophytic fungus Hypoxylon anthochroum strain Gseg1. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 169, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Feng, G.; Li, X.; Ruan, C.; Ming, J.; Zeng, K. Inhibition of three citrus pathogenic fungi by peptide PAF56 involves cell membrane damage. Foods 2021, 10, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Cho, H.S.; Ryu, S.Y.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, J. Coumarins reduce biofilm formation and the virulence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Sanz, A.B.; Bartual, S.G.; Wang, B.; Ferenbach, A.T.; Farkaš, V.; HurtadoGuerrero, R.; Arroyo, J.; Aalten, D.M.F. Mechanisms of redundancy and specificity of the Aspergillus fumigatus Crh transglycosylases. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.X.; Liang, X.G.; Cao, D.T.; Wu, H.L.; Xiao, S.L.; Liang, H.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.J.; Wei, H.Y.; Peng, W.W.; et al. Dictamnine suppresses the development of pear ring rot induced by Botryosphaeria dothidea infection by disrupting the chitin biosynthesis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 195, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.A.; Li, R.Y.; Mo, F.X.; Ding, Y.; Li, R.T.; Guo, X.; Hu, K.; Li, M. Natural product citronellal can significantly disturb chitin synthesis and cell wall integrity in Magnaporthe oryzae. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, S.; Wu, R. Inhibitory effect of carvacrol against Alternaria alternata causing goji fruit rot by disrupting the integrity and composition of cell wall. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1139749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.W.; Fu, X.X.; Cao, D.T.; Liang, X.G.; Xiao, S.L.; Yuan, M.X.; Huang, Y.J.; Zhou, Q.H.; Wei, H.Y.; Wang, J.W.; et al. The delaying effect of Clausena lansium extract on pear ring rot is related to its antifungal activity and induced disease resistance. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2024, 212, 112847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.T.; Wang, X.G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.Y.; Wu, Y.C.; Yao, J.; Cui, B.L.; Chen, Z. Anti-fungal activity of moutan cortex extracts against rice sheath blight (Rhizoctonia solani) and its action on the pathogen’s cell membrane. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 47048–47055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Fu, X.C.; Chang, X.; Ding, Z.M.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.S.; Wang, R.R.; Shan, Y.; Ding, S.H. The ester derivatives of ferulic acid exhibit strong inhibitory effect on the growth of Alternaria alternata in vitro and in vivo. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 196, 112158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wei, J.; Wei, Y.; Han, P.; Dai, K.; Zou, X.; Jiang, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; et al. Tea tree oil controls brown rot in peaches by damaging the cell membrane of Monilinia fructicola. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 175, 111474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Yu, Y.N.; Hu, Z.; Qian, S.A.; Zhao, Z.H.; Meng, J.J.; Zheng, S.M.; Huang, Q.W.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Nie, D.X.; et al. Antifungal Activity and Action Mechanisms of 2,4-Di-tertbutylphenol against Ustilaginoidea virens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17723–17732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.G.; Han, M.H.; He, F.; Wang, S.Y.; Li, C.H.; Wu, G.C.; Huang, Z.G.; Liu, D.; Liu, F.Q.; Laborda, P.; et al. Antifungal mechanism of dipicolinic acid and its efficacy for the biocontrol of pear valsa canker. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Compounds | VRE | EC50 (μg/mL) | R2 | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | microminutinin | y = 2.6466x + 2.2325 | 11.33 | 0.92 | 2.97–43.19 |

| 2 | carbendazim | y = 1.3096x + 3.8908 | 7.03 | 0.98 | 4.53–10.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, D.-T.; Yao, Y.-J.; Fu, X.-X.; Song, W.-W.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Q.-H.; Li, B.-T.; Peng, W.-W. Microminutinin, a Fused Bis-Furan Coumarin from Murraya euchrestifolia, Exhibits Strong Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity by Disrupting Cell Membranes and Walls. Plants 2025, 14, 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213392

Cao D-T, Yao Y-J, Fu X-X, Song W-W, Liu X-Y, Zhang P, Zhou Q-H, Li B-T, Peng W-W. Microminutinin, a Fused Bis-Furan Coumarin from Murraya euchrestifolia, Exhibits Strong Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity by Disrupting Cell Membranes and Walls. Plants. 2025; 14(21):3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213392

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Duan-Tao, Ying-Juan Yao, Xiao-Xiang Fu, Wen-Wu Song, Xin-Yuan Liu, Peng Zhang, Qing-Hong Zhou, Bao-Tong Li, and Wen-Wen Peng. 2025. "Microminutinin, a Fused Bis-Furan Coumarin from Murraya euchrestifolia, Exhibits Strong Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity by Disrupting Cell Membranes and Walls" Plants 14, no. 21: 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213392

APA StyleCao, D.-T., Yao, Y.-J., Fu, X.-X., Song, W.-W., Liu, X.-Y., Zhang, P., Zhou, Q.-H., Li, B.-T., & Peng, W.-W. (2025). Microminutinin, a Fused Bis-Furan Coumarin from Murraya euchrestifolia, Exhibits Strong Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity by Disrupting Cell Membranes and Walls. Plants, 14(21), 3392. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213392