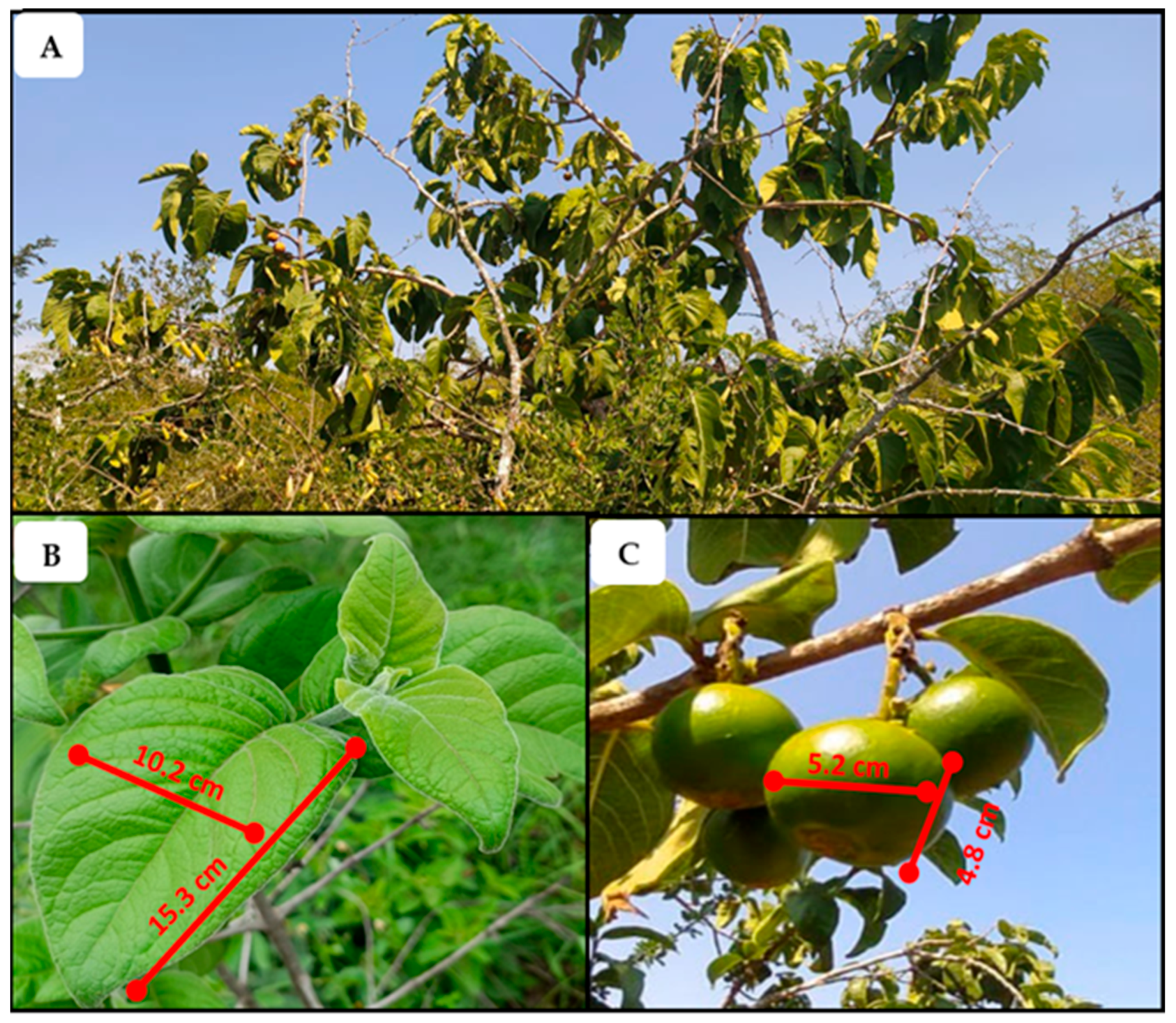

Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Vangueria infausta subsp. infausta Burch in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

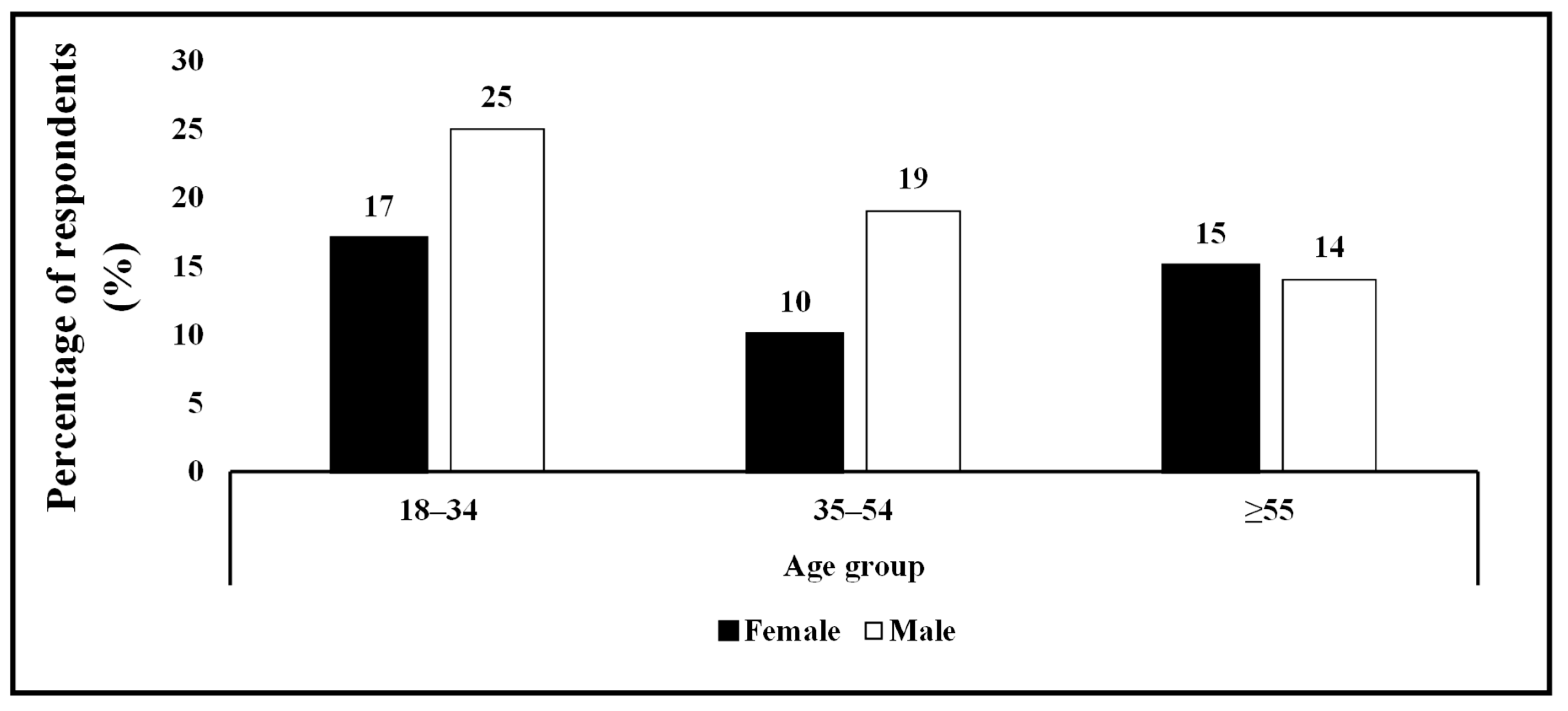

2.1. Socio-Demographic Information

2.2. The Significance of Umviyo, the Isizulu Name of Vangueria infausta (Wild Medlar)

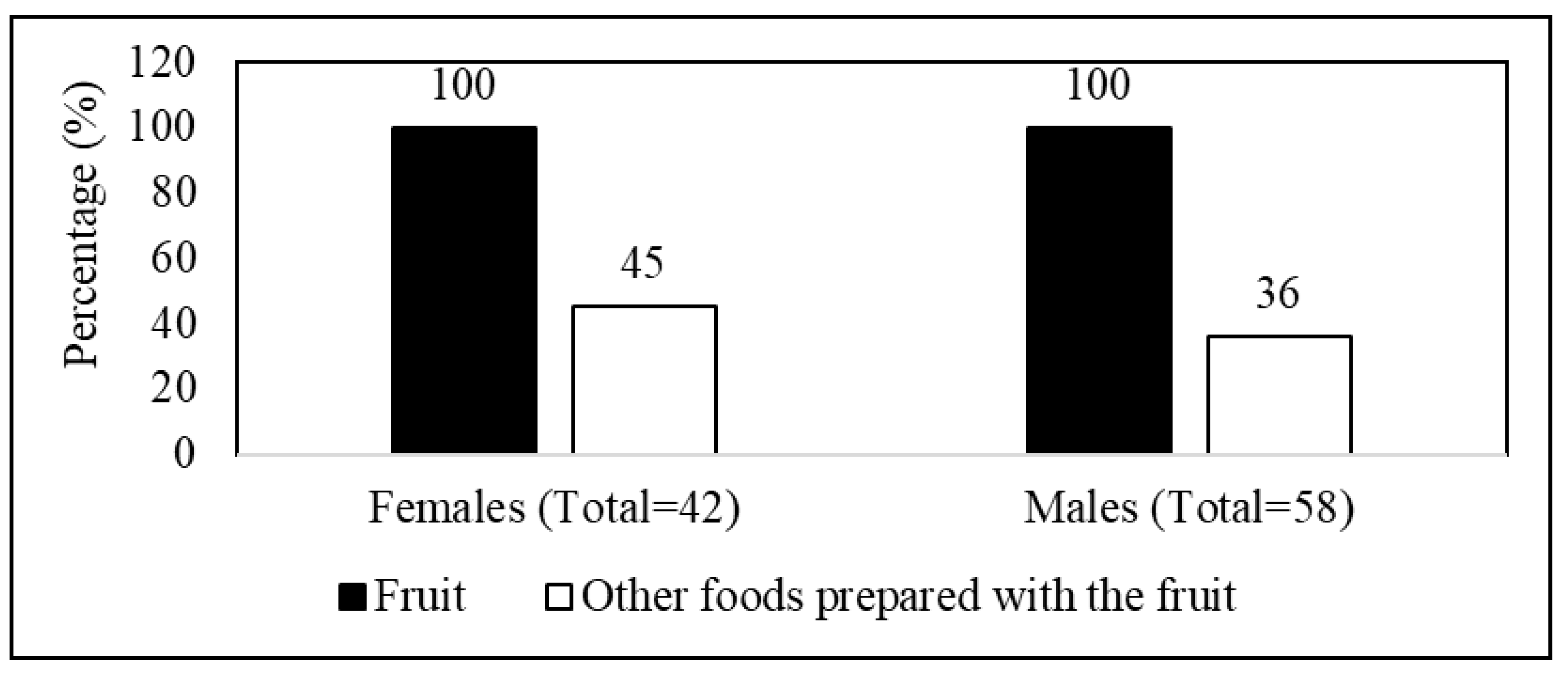

2.3. Consumption of Vangueria infausta (Wild Medlar) Fruit by the Community of Oyemeni

2.4. Medicinal and Other Uses of Vangueria infausta (Wild Medlar)

3. Discussion

3.1. Socio-Demographic Information

3.2. Significance of “Umviyo”, the IsiZulu Name of Wild Medlar

3.3. Consumption of Wild Medlar Fruit

3.4. Medicinal and Other Uses of Wild Medlar

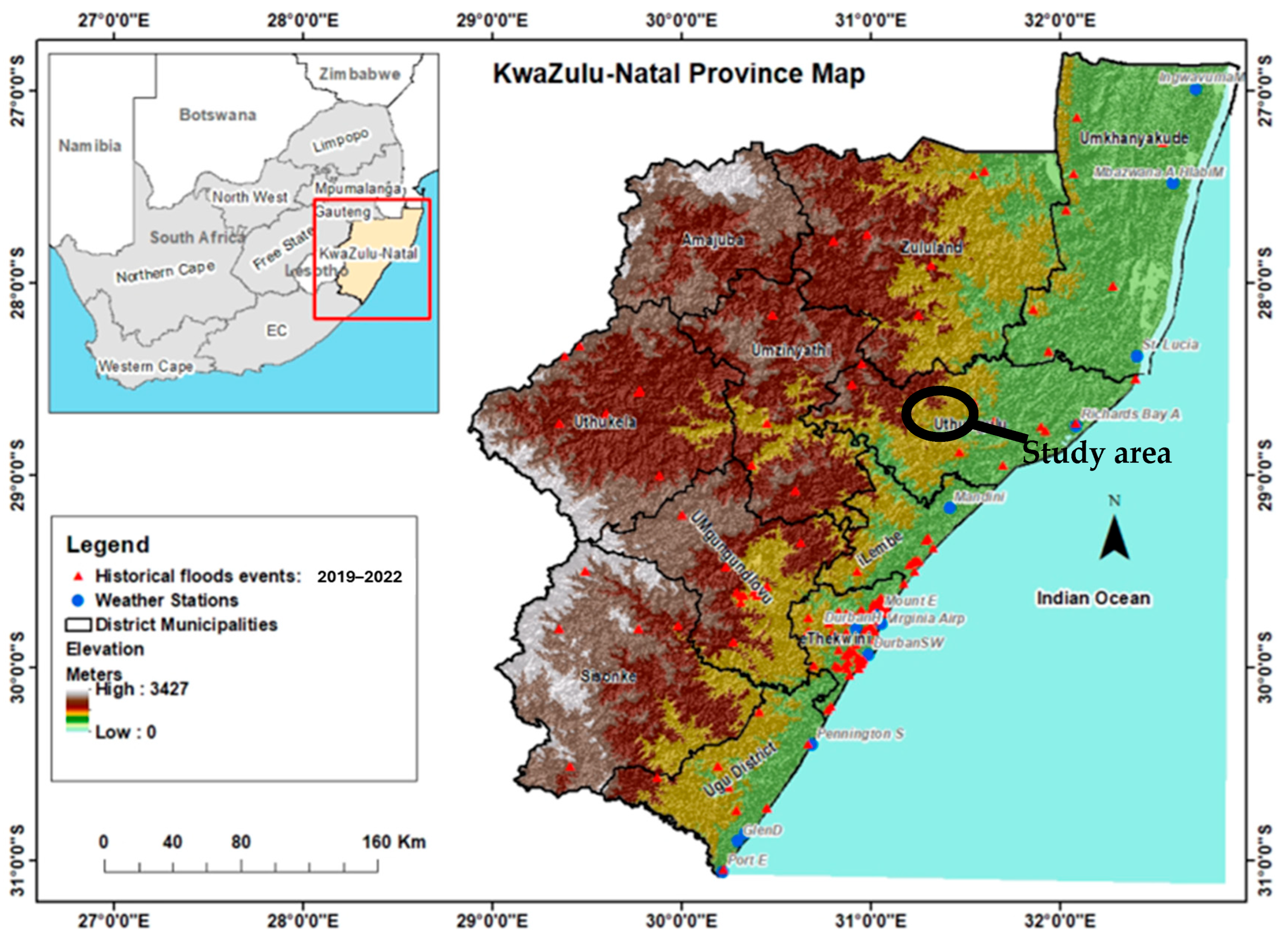

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Ethnobotanical Survey

4.3. Questionnaire Design

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Murugani, V.G.; Pereira, L.M.; Sobratee, N.; Govender, L.; Slotow, R.; Modi, A.T. Mainstreaming Underutilized Indigenous and Traditional Crops into Food Systems: A South African Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.; Borelli, T.; Beltrame, D.M.O.; Oliveira, C.N.S.; Coradin, L.; Wasike, V.W.; Wasilwa, L.; Mwai, J.; Manjella, A.; Samarasinghe, G.W.L.; et al. The potential of neglected and underutilized species for improving diets and nutrition. Planta 2019, 250, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroyi, A. Nutraceutical and ethnopharmacological properties of Vangueria infausta subsp. infausta. Molecules 2018, 23, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, A.; Scott, A.H.; Lewis, G.; Cunningham, A.B. Zulu Medicinal Plants, an Inventory; University of Natal Press Pietermaritzburg: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1996; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- Nkosi, N.N.; Mostert, T.H.C.; Dzikiti, S.; Ntuli, N.R. Prioritization of indigenous fruit tree species with domestication and commercialization potential in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Genet. Resources Crop Evolution. 2020, 67, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara-Leret, R.; Bascompte, J. Language extinction triggers the loss of unique medicinal knowledge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2103683118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlahla, M.O.; Kunene, L.A.; Mphekgwana, P.M.; Madiba, S.; Monyeki, K.D.; Modjadji, P. Comparison of malnutrition indicators and associated socio-demographic factors among children in rural and urban public primary schools in South Africa. Children 2023, 10, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.P.; Hinz, E.; Lang, D.J.; Tengö, M.; von Wehrden, H.; Martín-López, B. Indigenous and local knowledge in sustainability transformations research: A literature review. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, K.N.; Ncama, K.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Struwing, M.; Aremu, A.O. An exploratory study on the diverse uses and benefits of locally-sourced fruit species in three villages of Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Foods 2020, 9, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiau, E.; Francisco, J.D.C.; Bergenståhl, B.; Sjöholm, I. Softening of dried Vangueria infausta (African medlar) using maltodextrin and sucrose. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2013, 7, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemapare, P.; Gadaga, T.H.; Mugadza, D.T. Edible indigenous fruits in Zimbabwe: A review on the post-harvest handling, processing, and commercial value. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2229686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska, K.; Argumedo, A.; Wekesa, C.; Ndalilo, L.; Song, Y.; Rastogi, A.; Ryan, P. Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems and Biocultural Heritage: Addressing Indigenous Priorities Using Decolonial and Interdisciplinary Research Approaches. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, J.; Cifre, E. Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 384557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, N.; Mulrennan, M.E. “Part of Who We Are…”: A Review of the Literature Addressing the Sociocultural Role of Traditional Foods in Food Security for Indigenous People in Northern Canada. Societies 2024, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois, S.; Henry, A.G. The cost of gathering among the Baka forager-horticulturalists from southeastern Cameroon. Front. Ecology Evol. 2021, 9, 768003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, G. Indigenous knowledge and implications for the sustainable development agenda. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, J.R.; Aksoy, E.B.; Köse, N.; Okan, T.; Köse, C. What women know that men do not about chestnut trees in Turkey: A method of hearing muted knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. 2018, 38, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kom, Z.; Nethengwe, N.S. Indigenous and Local Knowledge: Instruments Towards Achieving SDG2: A Review in an African Context. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matandirotya, N.R.; Filho, W.L.; Mahed, G.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Mathe, P. Local knowledge of climate change adaptation strategies from the vhaVenda and baTonga communities living in the Limpopo and Zambezi River Basins, Southern Africa. Inland. Waters 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Maltitz, L.; Bahta, Y.T. The impact of indigenous practices to promote women’s empowerment in agriculture in South Africa. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1393582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Costa, F.V.; Guimarães, M.F.M.; Messias, M.C.T.B. Gender differences in traditional knowledge of useful plants in a Brazilian community. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, B.M.Q.; Perono Cacciafoco, F. Botanical Roots and Word Origins: A Systematic Reconstruction of Alor Plant Name Etymologies. Histories 2024, 4, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapane, O.L.; Chanza, N.; Musakwa, W. Transmission of indigenous knowledge systems under changing landscapes within the vhavenda community, South Africa. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 161, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaoue, O.E.; Coe, M.A.; Bond, M.; Hart, G.; Seyler, B.C.; McMillen, H. Theories and Major Hypotheses in Ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 2017, 71, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxele, B.J.; Mdletshe, B.A.; Memela, B.E.; Nxumalo, M.M.; Sithole, H.J.; Mlaba, P.J.; Nhleko, K.; Zulu, Z.; Zuke, L.; Mchunu, S.; et al. Naming invasive alien plants into indigenous languages: KwaZulu-Natal case study, South Africa. J. Biodivers. For. 2019, 8, 1000207. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, A. The interface between magic, plants and language. S. Afr. Humanit. 2013, 25, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mbelebele, Z.; Mdoda, L.; Ntlanga, S.S.; Nontu, Y.; Gidi, L.S. Harmonizing Traditional Knowledge with Environmental Preservation: Sustainable Strategies for the Conservation of Indigenous Medicinal Plants (IMPs) and Their Implications for Economic Well-Being. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Salim, J.; Anuar, S.N.; Omar, K.; Tengku Mohamad, T.R.; Sanusi, N.A. The Impacts of Traditional Ecological Knowledge towards Indigenous Peoples: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathoure, A.K. Cultural practices to protecting biodiversity through cultural heritage: Preserving nature, preserving culture. Biodivers. Int. 2024, 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashile, S.P.; Tshisikhawe, M.P.; Masevhe, N.A. Indigenous fruit plants species of the Mapulana of Ehlanzeni district in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluleke, M.K.; Ralulimi, T.S.; Machete, M. Biological constituents and the role of African wild medlar (Vangueria infausta) in human nutrition: A review. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legwaila, G.M.; Mojeremane, W.; Madisa, M.E.; Mmolotsi, R.M.; Rampart, M. Potential of traditional food plants in rural household food security in Botswana. J. Hortic. For. 2011, 3, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Teixidor-Toneu, I.; Elgadi, S.; Zine, H.; Manzanilla, V.; Ouhammou, A.; D’Ambrosio, U. Medicines in the Kitchen: Gender Roles Shape Ethnobotanical Knowledge in Marrakshi Households. Foods 2021, 10, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, B.; Bergh, S.I. Why women’s traditional knowledge matters in the production processes of natural product development: The case of the Green Morocco Plan. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum. 2019, 77, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbhele, Z.; Zharare, G.E.; Zimudzi, C.; Ntuli, N.R. Indigenous knowledge on the uses and morphological variation among Strychnos spinosa Lam. at Oyemeni area, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, T.P.; Schönfeldt, H.C.; Vermeulen, H. Consumer acceptability and perceptions of maize meal in Giyani, South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2011, 28, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affonfere, M.; Madode, Y.E.; Chadare, F.J.; Azokpota, P.; Hounhouigan, D.J. A dual food-to-food fortification with moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaf powder and baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) fruit pulp increases micronutrients solubility in sorghum porridge. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, T.F.; Salgaço, M.K.; Oliveira, G.L.V.d.; Carvalho, L.A.L.d.; Pinheiro, D.G.; Todorov, S.D.; Sivieri, K.; Casarotti, S.N.; Penna, A.L.B. Functional Fermented Milk with Fruit Pulp Modulates the In Vitro Intestinal Microbiota. Foods 2022, 11, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleke, M.S.; Adefisoye, M.A.; Doorsamy, W.; Adebo, O.A. Processing, nutritional composition and microbiology of amasi: A Southern African fermented milk product. Sci. Afr. 2021, 12, e00795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejayan, J.; Bathmanathan, R.; Tuan Said, S.A.; Chakravarthi, S.; Ibrahim, H. Fruit extract derived from a mixture of noni, pineapple and mango capable of coagulating milk and producing curd with antidiabetic activities. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 60, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaia, T.; Uamusse, A.; Sjöholm, I.; Skog, K. Proximate analysis of five wild fruits of Mozambique. Sci. World J. 2013, 1, 601435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilonu, M.C.; Ngubane, X.V.; Jiyane, P.C. Phytochemicals, bioactivity, and ethnopharmacological potential of selected indigenous plants. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2023, 119, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiau, E. Utilization of Wild Fruit in Mozambique–Drying of Vangueria infausta (African medlar); Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, E.M.F.; Ramos, A.M.; Martins, M.L.; Leite Júnior, B.R.D.C. Fruit salad as a new vehicle for probiotic bacteria. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Boobyer, C.; Borgonha, Z.; van den Heuvel, E.; Appleton, K.M. Adding flavours: Use of and attitudes towards sauces and seasonings in a sample of community-dwelling UK older adults. Foods 2021, 10, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B.; Jung, C. Embracing Tradition: The Vital Role of Traditional Foods in Achieving Nutrition Security. Foods 2023, 12, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwurah, G.O.; Okeke, F.O.; Isimah, M.O.; Enoguanbhor, E.C.; Awe, F.C.; Nnaemeka-Okeke, R.C.; Guo, S.; Nwafor, I.V.; Okeke, C.A. Cultural Influence of Local Food Heritage on Sustainable Development. World 2025, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The Future of Food. Foods 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, H.; Hedberg, I.; Bandeira, S.; Ghorbani, A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal and edible plants used in Nhamacoa area, Manica Province–Mozambique. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 139, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, V.L.; Whiting, M.J. A picture of health? Animal use and the Faraday traditional medicine market, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 179, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane, Z.P. Indigenous Knowledge on Tree Conservation in Swaziland. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lauter, O. Challenges in combining Indigenous and scientific knowledge in the Arctic. Polar Geogr. 2023, 46, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.C.; Rahman, H.; Alam, J.; Faruque, M.O.; Mahamudul, M. A comparative analysis of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal healers in villages adjoining the Ghaghot, Bangali and Padma Rivers of Bangladesh. Am.-Eurasian J. Sustain. Agric. 2010, 4, 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shikwambana, N.; Mahlo, S.M. A survey of antifungal activity of selected South African plant species used for the treatment of skin infections. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20923181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, G.; Badran, A.; Hijazi, A.; Daou, A.; Baydoun, E.; Nasser, M.; Merah, O. The TherapeuticWound Healing Bioactivities of Various Medicinal Plants. Life 2023, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kose, R.; Sogut, O.; Demir, T.; Koruk, I. Hemostatic efficacy of folkloric medicinal plant extract in a rat skin bleeding model. Dermatol. Surg. 2012, 38, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogut, O.; Erdogan, M.O.; Kose, R.; Boleken, M.E.; Kaya, H.; Gokdemir, M.T.; Ozgonul, A.; Iynen, I.; Albayrak, L.; Dokuzoglu, M.A. Hemostatic efficacy of a traditional medicinal plant extract (Ankaferd Blood Stopper) in bleeding control. Clin. Appl. Thromb./Hemost. 2015, 21, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moichwanetse, B.I.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Sedupane, G.; Aremu, A.O. Ethno-veterinary plants used for the treatment of retained placenta and associated diseases in cattle among Dinokana communities, North-West Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 132, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakale, M.V.; Asong, J.A.; Struwig, M.; Mwanza, M.; Aremu, A.O. Ethnoveterinary Practices and Ethnobotanical Knowledge on Plants Used against Cattle Diseases among Two Communities in South Africa. Plants 2022, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The King Cetshwayo Integrated Development Plan Review 2023/2024. Available online: https://www.kingcetshwayo.gov.za/index.php/documents/2-idp/13-2023-2024 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Sidiq, F.F.; Coles, D.; Hubbard, C.; Clark, B.; Frewer, L.J. The role of traditional diets in promoting food security for indigenous peoples in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 978, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashao, F.M.; Mothapo, M.C.; Munyai, R.B.; Letsoalo, J.M.; Mbokodo, I.L.; Muofhe, T.P.; Matsane, W.; Chikoore, H. Extreme rainfall and flood risk prediction over the East Coast of South Africa. Water 2023, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku, M.M.; Bhengu, A.S. The value of indigenous foods in improving food security in Emaphephetheni rural setting. Indilinga Afr. J. Indig. Knowl. Syst. 2021, 20, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mgwenya, L.I.; Agholor, I.A.; Ludidi, N.; Morepje, M.T.; Sithole, M.Z.; Msweli, N.S.; Thabane, V.N. Unpacking the Multifaceted Benefits of Indigenous Crops for Food Security: A Review of Nutritional, Economic and Environmental Impacts in Southern Africa. World 2025, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangjang, S.; Namsa, N.D.; Aran, C.; Litin, A. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in the Eastern Himalayan zone of Arunachal Pradesh, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food | Participants | Gender | Age Group (Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G [N (%)] | 18–34 N (TP; TGP) | 35–54 N (TP; TGP) | ≥55 (TP; TGP) | ||

| Fruit | 100 | F [42 (42)] M [58 (58)] | 17 (17; 40) 25 (25; 43) | 10 (10; 24) 19 (19; 33) | 15 (15; 36) 14 (14; 24) |

| Fermented maize meal (umBhantshi) | 13 | F [7 (54)] M [6 (46)] | 0 (0; 0) 3 (23; 50) | 1 (8; 14) 1 (8; 17) | 6 (46; 86) 2 (15; 33) |

| Maize porridge | 9 | F [5 (55)] M [4 (44)] | 5 (55; 100) 3 (33; 75) | 0 (0; 0) 1 (11; 25) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Juice | 6 | F [2 (33)] M [4 (67)] | 0 (0; 0) 2 (33; 50) | 0 (0; 0) 1 (17; 25) | 2 (33; 100) 1 (17; 25) |

| Alcohol | 5 | F [1 (20)] M [4 (80)] | 1 (20; 100) 4 (80; 100) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Fermented maize porridge (amaHewu) | 3 | F [2 (67)] M [1 (33)] | 0 (0; 0) 1 (33; 100) | 2 (67; 100) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Fruit salad | 2 | F [2 (100)] M [0 (0)] | 1 (50; 50) 0 (0; 0) | 1 (50; 50) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Milk curdling (Amasi) | 1 | F [0 (0)] M [1 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 1 (100; 100) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Sour porridge (umNcindo) | 1 | F [0 (0)] M [1 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) 1 (100; 100) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Use | Participants | Gender | Age (Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G [N (%)] | 18–34 N (TP; TGP) | 35–54 N (TP; TGP) | ≥55 N (TP; TGP) | ||

| Toothbrushing | 11 | F [2 (18)] M [9 (82)] | 1 (9; 50) 3 (27; 33) | 1 (9; 50) 4 (36; 44) | 0 (0; 0) 2 (18; 22) |

| Toothache | 10 | F [4 (40)] M [6 (60)] | 4 (40; 100) 3 (30; 50) | 0 (0; 0) 3 (30; 50) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Protection against evil spirits | 8 | F [0 (0)] M [8 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) 2 (25; 25) | 0 (0; 0) 3 (38; 38) | 0 (0; 0) 3 (38; 38) |

| Not as firewood | 5 | F [1 (20)] M [4 (80)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 3 (60; 75) | 1 (20; 100) 1 (20; 25) |

| Wetting the bed | 5 | F [2 (40)] M [3 (60)] | 1 (20; 50) 2 (40; 67) | 1 (20; 50) 1 (20; 33) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| As a toilet wipe | 4 | F [1 (25)] M [3 (75)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 3 (75; 100) | 1 (25; 100) 0 (0; 0) |

| Firewood | 4 | F [1 (25)] M [3 (75)] | 0 (0; 0) 1 (25; 33) | 0 (0; 0) 2 (50; 67) | 1 (25; 100) 0 (0; 0) |

| Bring unity and courage for warriors | 4 | F [0 (0)] M [4 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) 3 (75; 75) | 0 (0; 0) 1 (25; 25) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Wound healing | 4 | F [3 (75)] M [1 (25)] | 2 (50; 67) 1 (25; 100) | 1 (25; 33) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Stomachache | 3 | F [2 (67)] M [1 (33)] | 1 (33; 50) 1 (33; 100) | 1 (33; 50) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Prevents cow miscarriage | 2 | F [1 (50)] M [1 (50)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 1 (50; 100) | 1 (50; 100) 0 (0; 0) |

| Wiping fat off the dishes | 1 | F [1 (100)] M [0 (0; 0)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 1 (100; 100) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Stops bleeding | 1 | F [1 (100)] M [0 (0)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 1 (100; 100) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Earache | 1 | F [0 (0)] M [1 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) 1 (100; 100) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Steaming | 1 | F [1 (100)] M [0 (0)] | 1 (100; 100) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

| Vomiting | 1 | F [0 (0)] M [1 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) 1 (100; 100) | 0 (0; 0) 0 (0; 0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngubane, S.C.; Mbhele, Z.; Ntuli, N.R. Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Vangueria infausta subsp. infausta Burch in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Plants 2025, 14, 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121820

Ngubane SC, Mbhele Z, Ntuli NR. Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Vangueria infausta subsp. infausta Burch in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Plants. 2025; 14(12):1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121820

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgubane, Samukelisiwe Clerance, Zoliswa Mbhele, and Nontuthuko Rosemary Ntuli. 2025. "Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Vangueria infausta subsp. infausta Burch in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa" Plants 14, no. 12: 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121820

APA StyleNgubane, S. C., Mbhele, Z., & Ntuli, N. R. (2025). Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Uses of Vangueria infausta subsp. infausta Burch in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Plants, 14(12), 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14121820