Spatial Reconfiguration of Living Stems and Snags Reveals Stand Structural Simplification During Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J.Houz.) Invasion into Coniferbroad-Leaf Forests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Moso Bamboo Expansion on Composition of Living Stems and Snags

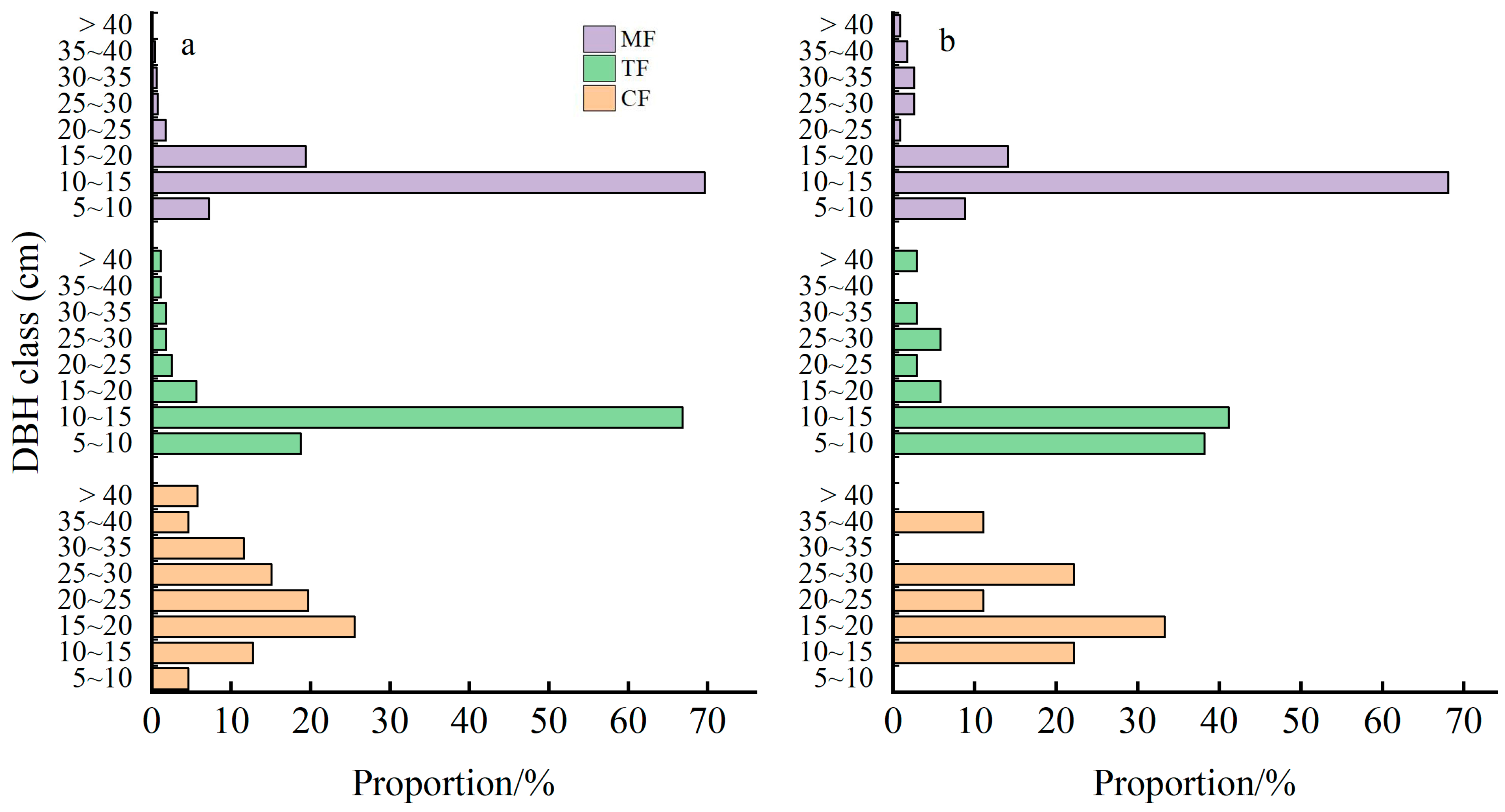

2.2. Effects of Moso Bamboo Expansion on Diameter Class Structure of Living Stems and Snags

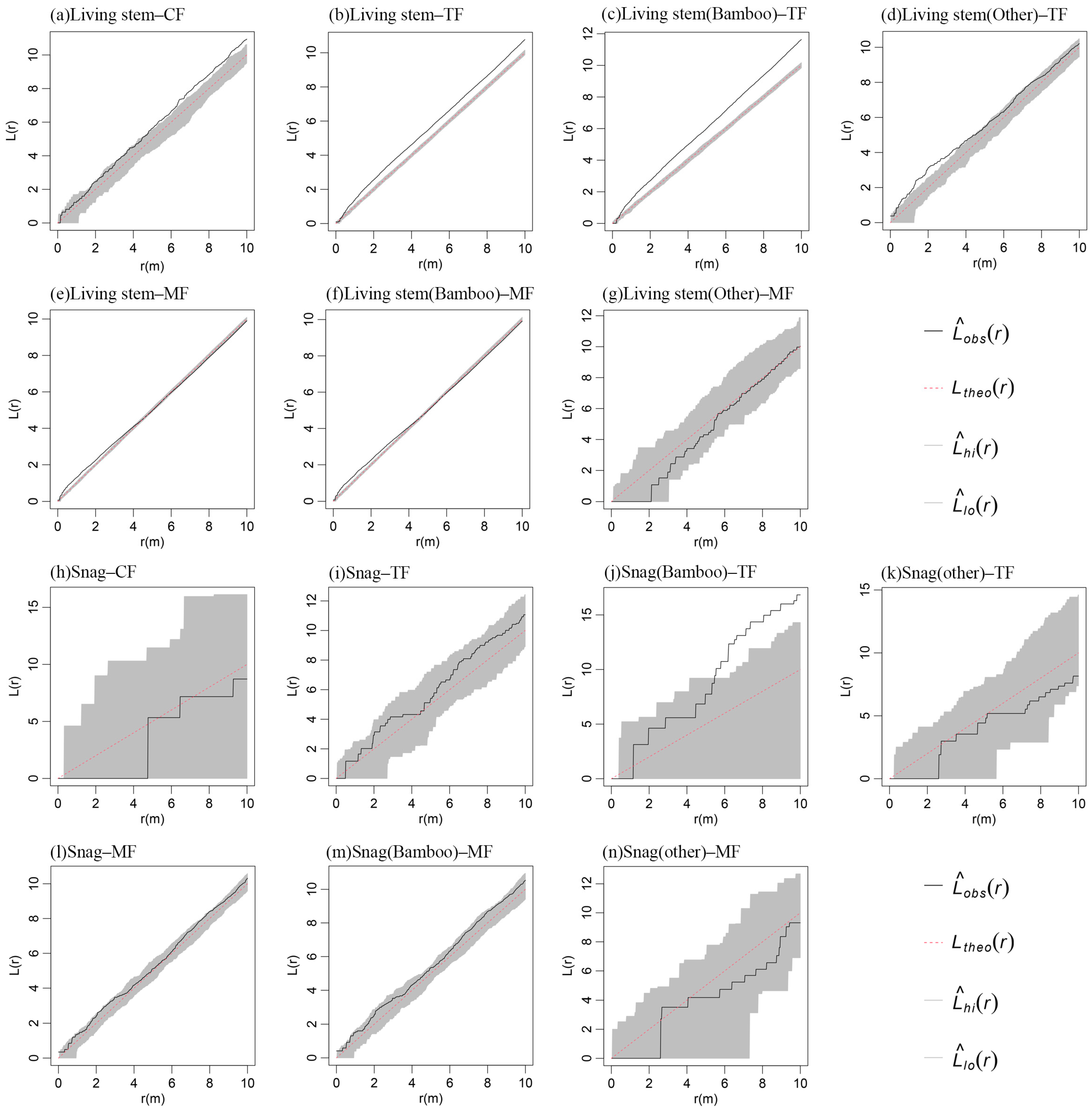

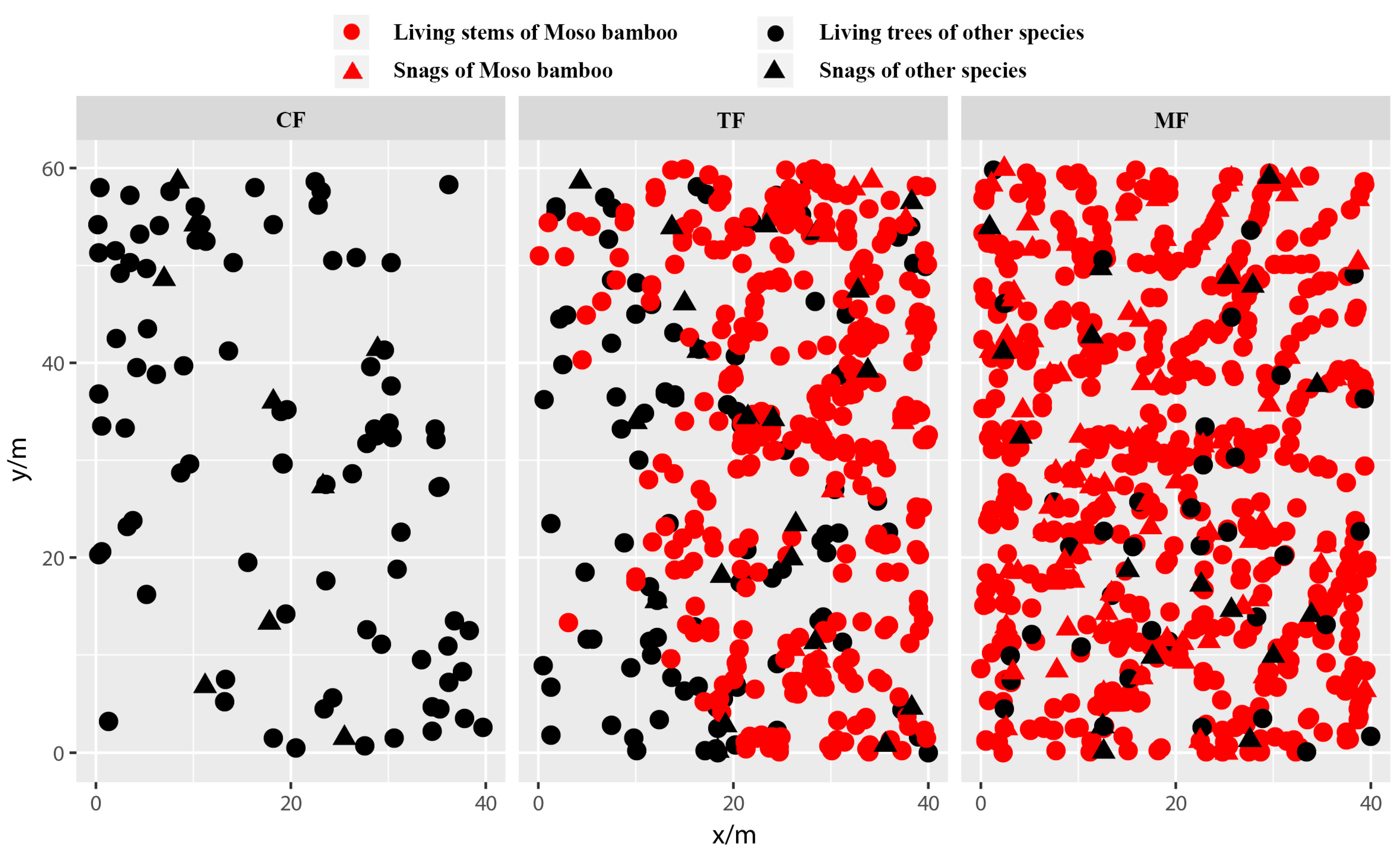

2.3. Effects of Moso Bamboo Expansion on Spatial Distribution Patterns of Living Stems and Snags

2.4. Spatial Associations of Standing Stems Across Moso Bamboo Expansion Stages

3. Discussion

4. Research Site and Methods

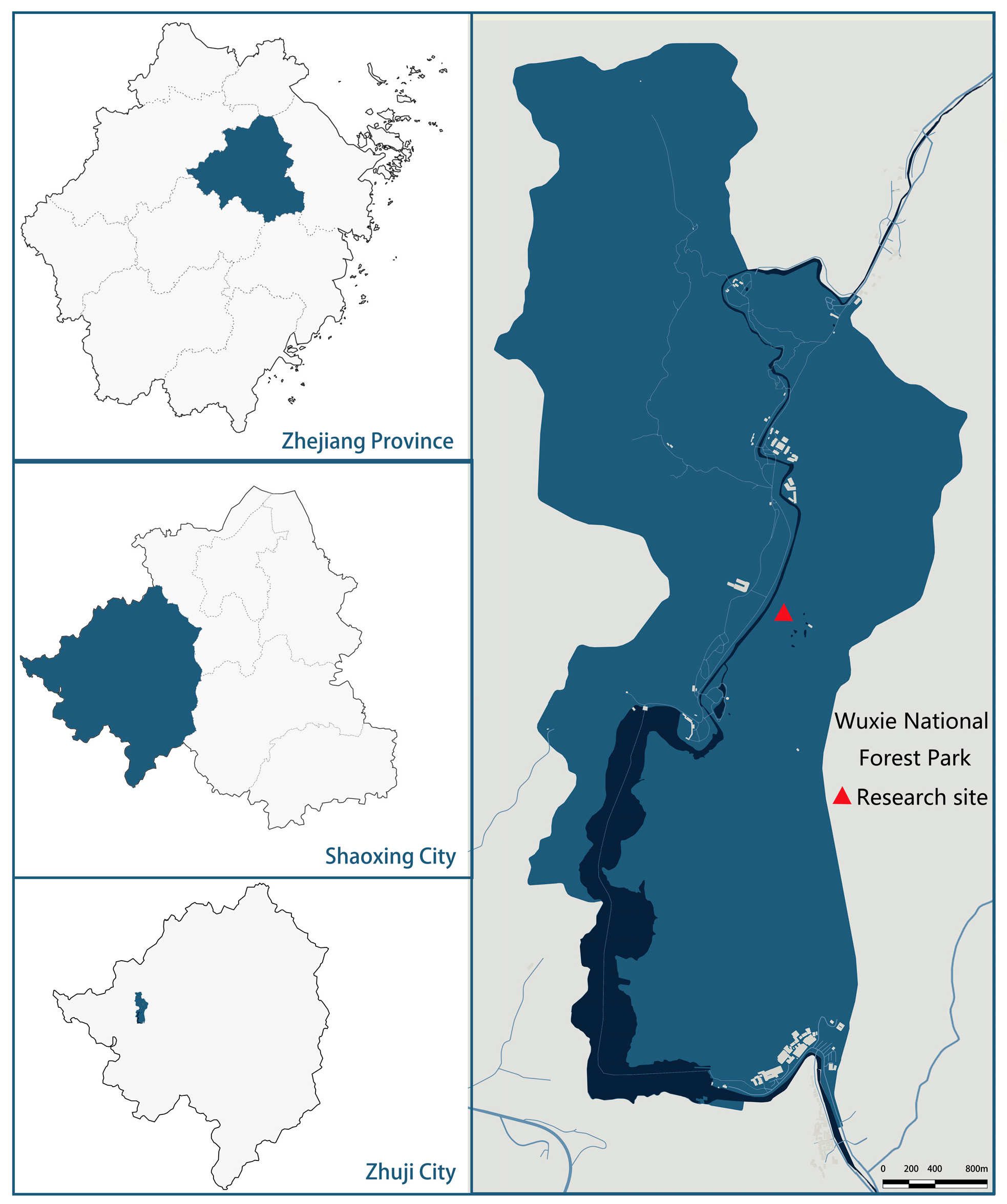

4.1. Research Site

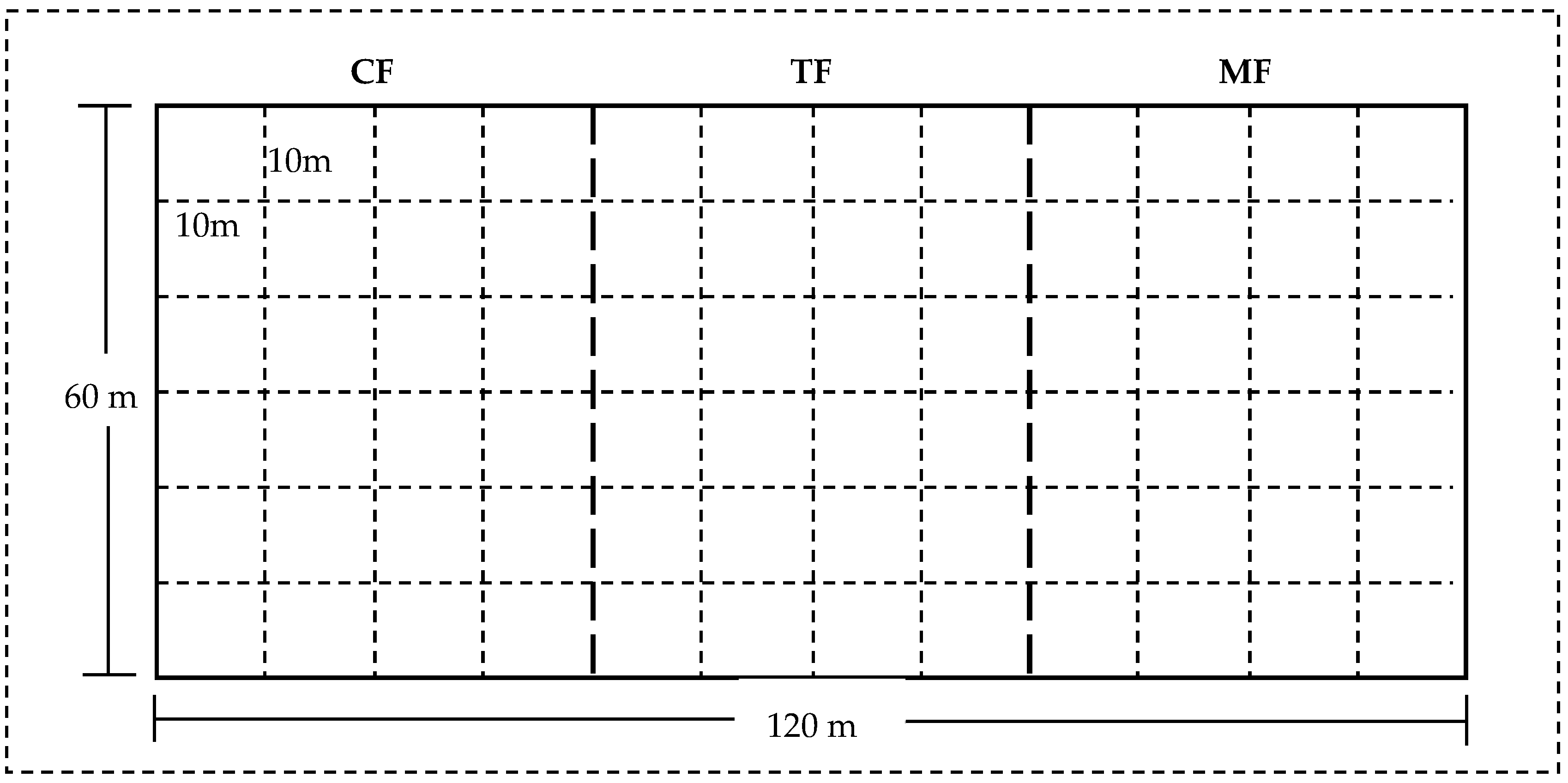

4.2. Experimental Design and Methodology

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Early Expansion Phase: The surrounding forest community (CF) exhibits high tree species diversity with unimodal diameter-class structures. Living stems and snags have random spatial patterns. Tree mortality is primarily driven by environmental stressors and senescence processes.

- (2)

- Middle Expansion Phase: The forest community (TF) exhibits intensified competitive dynamics, characterized by species diversity decline, diameter-class structures simplification, tree mortality rates increase significantly, and clustered distribution of living stems/snags. Intra- and inter-species competition becomes the dominant cause of plant death.

- (3)

- Late Expansion Phase: Moso bamboo establishes absolute dominance within the plant community, leading to weakened aggregating of both living stems and snags, and stabilized forest succession with negligible structural or spatial dynamics.

- (4)

- Overall Impact: Moso bamboo expansion drives stand structural simplification through spatial decoupling of live stems and snags in adjacent forest stands across all stages.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, H.; Zhou, D.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Ren, Y.; Yang, X. Disparity in the relative roles of biotic and abiotic drivers on tree mortality between warm-temperate and temperate forests in China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 537, 120938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Z. Spatial-temporal dependence of the neighborhood interaction in regulating tree growth in a tropical rainforest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 508, 120032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.E.; Bell, D.M. Mortality in forested ecosystems: Suggested conceptual advances. Forests 2020, 11, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Li, Y. China’s Bamboo Resources in 2021. World Bamboo Ratt. 2023, 21, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Griscom, B.W.; Ashton, P.M.S. Bamboo control of forest succession: Guadua sarcocarpa in Southeastern Peru. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 175, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.H.; Canham, C.D.; Marks, P.L. Why forests appear resistant to exotic plant invasions: Intentional introductions, stand dynamics, and the role of shade tolerance. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Wang, Y.; Conant, R.T.; Zhou, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Fang, F.; Chen, J. Can native clonal moso bamboo encroach on adjacent natural forest without human intervention? Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31504. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Shen, J.-X.; Guo, Z.-W.; Lei, J.-P.; Li, J.-M.; Yu, F.-H.; Li, M.-H. Shoot removal interacts with soil temperature to affect survival, growth and physiology of young ramets of a bamboo. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 481, 118735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, S.; Binkley, D.; Zhou, G.; Fang, F. The independence of clonal shoot’s growth from light availability supports moso bamboo invasion of closed-canopy forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 368, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhong, Y.; Li, D.; Deng, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z. Expansion of Naturally Grown Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J. Houzeau Forests into Diverse Habitats: Rates and Driving Factors. Forests 2024, 15, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Huang, K.; Ning, Y.; Bi, Y. Allelochemicals from Moso Bamboo: Identification and Their Effects on Neighbor Species. Forests 2024, 15, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Eziz, A.; Xiao, S.; Fang, W.; Cai, Q.; Ma, S.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Q.; Hu, J.; Tang, Z. Effects of bamboo invasion on forest structures and diameter–height allometries. For. Ecosyst. 2025, 12, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, S.; Fang, D. Impacts of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) invasion on species diversity and aboveground biomass of secondary coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1001785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, J. Spatial pattern and competitive relationships of moso bamboo in a native subtropical rainforest community. Forests 2018, 9, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Conant, R.T.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K. Effects of moso bamboo encroachment into native, broad-leaved forests on soil carbon and nitrogen pools. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, M.J.; Helton, A.M.; White, J.C.; Smith, W.K. Standing dead trees are a conduit for the atmospheric flux of CH4 and CO2 from wetlands. Wetlands 2018, 38, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, J.W. Fungal inoculations and mechanical wounding of trees have limited efficacy for snag creation two decades after treatment. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 553, 121651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.W.; Thill, R.E. Comparison of snag densities among regeneration treatments in mixed pine–hardwood forests. Can. J. For. Res. 2013, 43, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, H.; Junninen, K.; Boberg, J.; Tatsumi, S.; Stenlid, J.; Kouki, J. Life after tree death: Does restored dead wood host different fungal communities to natural woody substrates? For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 409, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z. Spatial analyses of invasion patterns of Chinese tallow (Triadica sebifera) in a wet slash pine (Pinus elliottii) flatwood in the coastal plain of Mississippi, USA. For. Sci. 2018, 64, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Fortin, M.J. Spatial pattern and ecological analysis. Vegetatio 1989, 80, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. Spatial patterns of the main trees in a plant micro-reserve constructed in the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics mountainous competition zone. J. Mt. Sci. 2023, 20, 2228–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Turner, R. Spatstat: An R package for analyzing spatial point patterns. J. Stat. Softw. 2005, 12, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Tang, M.; Lou, M.; Shen, L.; Pang, C.; Zou, Y. Analysis of the spatial structure and competition with a Phyllostachys edulis standbased on an improved Hegyi model. Acta Ecol. Sin 2016, 36, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, M. Relationship between spatial structure and biomass of a close-to-nature Phyllostachys edulis stand in Tianmu mountain. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2011, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Tang, M.; Zhao, S.; Du, X.; Shen, Q.; Pang, C. Competitive spatial patterns for Moso bamboo on Mount Tianmu. J. Zhejiang A&F Univ. 2018, 35, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A.; Lv, J. Spatial patterns of bamboo expansion across scales: How does Moso bamboo interact with competing trees? Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 3925–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, Y.; Kohyama, T.S.; Kubo, T.; Kassim, A.R.; Poorter, L.; Sterck, F.; Potts, M.D. Tree architecture and life-history strategies across 200 co-occurring tropical tree species. Funct. Ecol. 2011, 25, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xiong, Z.; Yang, T. Spatial point pattern analysis for coarse woody debris in karst mixed evergreen and deciduous broadleaved forest. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 4933–4943. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, Y.; Fang, F. Stand structure change of Phyllostachys pubescens forest expansion in Tianmushan National Nature Reserve. J. West China For. Sci. 2012, 41, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- LIU, X.; FAN, S.; LIU, G.; PENG, C. Changing characteristics of main structural indexes of community during the expansion of moso bamboo forests. Chin. J. Ecol. 2016, 35, 3165. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Wang, S.; Feng, J.; Sang, W. Spatial distribution patterns of snag and standing trees in a warm temperate deciduous broad-leaved forest in Dongling Mountain, Beijing. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 5717–5725. [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, C.G.; Dahir, S.E.; Nordheim, E.V. Tree mortality rates and longevity in mature and old-growth hemlock-hardwood forests. J. Ecol. 2001, 89, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Yan, H.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, X. Quantitative characteristics and distribution pattern of living and dead standing trees of secon-dary Picea forest in Guandi Mountain, northern China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 3061–3069. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, G.; Song, Q.; Shi, J.; Ouyang, M.; Qi, H.; Fang, X. Ecological studies on bamboo expansion: Process, consequence and mechanism. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2015, 39, 110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Escandón, A.B.; Paula, S.; Rojas, R.; Corcuera, L.J.; Coopman, R.E. Sprouting extends the regeneration niche in temperate rain forests: The case of the long-lived tree Eucryphia cordifolia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 310, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Wang, S.; Sang, W.; Ma, K. Spatial Pattern of Living Woody and Coarse Woody Debris in Warm-Temperate Broad-Leaved Secondary Forest in North China. Plants 2024, 13, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Lang, X.; Hu, Z.; Shang, R.; Liu, W. Spatial pattern of dominant species with different seed dispersal modes in a monsoon evergreen broad-leaved forest in Pu’er, Yunnan Province. Biodivers. Sci. 2023, 31, 23147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F. A study on the structure and dynamics of the Cyclobalanopsis glauca populations in the hills around West Lake in Hangzhou. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2000, 36, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, H.; An, L. Spatial patterns and interspecific relationships of two dominant cushion plants at three elevations on the Kunlun Mountain, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 17339–17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.; Zheng, L.; Jia, H.; Lu, L.; Huang, D.; Huang, B.; Lei, L. Community characteristics and spatial distribution of dominant tree species in a secondary forest of Daqing Mountains, southwestern Guangxi, China. Biodivers. Sci. 2015, 23, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sheng, H.; Jin, X. Study on arbor community characteristics of secondary evergreen broadleaved forest and coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest in Tonglingshan National Forest Park of Zhejiang Province. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2019, 28, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A.; Pacala, S.W. The enigmatic life history of the bamboo explained as a strategy to arrest succession. Ecol. Monogr. 2024, 94, e1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Huang, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Pattern analysis of inter-specific relationships in four arid communities in Sand Lake, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2009, 33, 320. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand, T.; Moloney, K.A. Rings, circles, and null-models for point pattern analysis in ecology. Oikos 2004, 104, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, B.D. Modelling spatial patterns. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1977, 39, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Rubak, E.; Turner, R. Spatial Point Patterns: Methodology and Applications with R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lotwick, H.; Silverman, B. Methods for analysing spatial processes of several types of points. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1982, 44, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Guo, S.; Yang, Q.; Wang, B.; Yang, G.; Fang, K. Inhomogeneous spatial point pattern analysis of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 4401–4407. [Google Scholar]

| Objective Stems | Stand Types | Stem Species | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phyllostachys edulis | Schima superba | Castanopsis eyrei | Pinus massoniana | Cyclobalanopsis glauca | Liquidambar formosana | Cunninghamia lanceolata | Others | Total | |||

| Density/ (stem·ha−1) | living stems | CF | 0 c | 100 a | 63 a | 50 a | 38 a | 33 b | 29 a | 46 a | 358 c |

| TF | 1354 b | 83 a | 79 a | 63 a | 58 a | 71 a | 21 a | 46 a | 1775 b | ||

| MF | 2438 a | 4 b | 75 a | 33 a | 42 a | 0 c | 0 b | 0 b | 2592 a | ||

| Snags | CF | 0 c | 8 a | 4 a | 8 a | 4 a | 4 a | 8 a | 0 a | 38 c | |

| TF | 54 b | 17 a | 17 a | 17 a | 29 a | 4 a | 4 a | 0 a | 142 b | ||

| MF | 396 a | 8 a | 13 a | 33 a | 13 a | 0 a | 8 a | 0 a | 471 a | ||

| Basal area/ (m2·ha−1) | living stems | CF | 0 c | 4.64 a | 2.50 a | 3.93 ab | 0.58 a | 2.11 a | 1.92 a | 1.12 a | 17.03 c |

| TF | 15.36 b | 2.34 ab | 1.28 a | 7.37 a | 0.95 a | 2.68 a | 0.21 ab | 0.52 a | 30.72 b | ||

| MF | 34.03 a | 0.08 b | 2.74 a | 2.34 b | 1.02 a | 0 b | 0 b | 0 b | 40.48 a | ||

| Snags | CF | 0 c | 0.26 a | 0.06 a | 0.55 a | 0.08 a | 0.03 a | 0.58 a | 0 a | 1.55 b | |

| TF | 0.47 b | 0.20 a | 0.17 a | 1.31 a | 0.27 a | 0.04 a | 0.26 a | 0 a | 2.71 b | ||

| MF | 5.12 a | 0.08 a | 0.26 a | 2.84 a | 0.27 a | 0 a | 0.78 a | 0 a | 9.36 a | ||

| Stand Types | Average Altitude | Slop Aspect | Slop Degree | Average Diameter | Dominant Families | Dominant Species | Life Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 228 m | WN | 8° | 22.9 cm | Fagaceae | Schima superba | Tree |

| Theaceae | Castanopsis eyrei | Tree | |||||

| Pinaceae | Pinus massoniana | Tree | |||||

| Altingiaceae | Cyclobalanopsis glauca | Tree | |||||

| Cupressaceae | Liquidambar formosana | Tree | |||||

| TF | 236 m | WN | 14° | 13.38 cm | Poaceae | Phyllostachys edulis | Grass |

| Fagaceae | Schima superba | Tree | |||||

| Theaceae | Castanopsis eyrei | Tree | |||||

| Altingiaceae | Liquidambar formosana | Tree | |||||

| Pinaceae | Pinus massoniana | Tree | |||||

| MF | 242 m | WN | 15° | 13.78 cm | Poaceae Fagaceae Pinaceae | Phyllostachys edulis | Grass |

| Castanopsis eyrei | Tree | ||||||

| Cyclobalanopsis glauca | Tree | ||||||

| Pinus massoniana | Tree |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Jin, S.; Bai, S. Spatial Reconfiguration of Living Stems and Snags Reveals Stand Structural Simplification During Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J.Houz.) Invasion into Coniferbroad-Leaf Forests. Plants 2025, 14, 1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14111698

Chen X, Zhou X, Jin S, Bai S. Spatial Reconfiguration of Living Stems and Snags Reveals Stand Structural Simplification During Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J.Houz.) Invasion into Coniferbroad-Leaf Forests. Plants. 2025; 14(11):1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14111698

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xi, Xiumei Zhou, Songheng Jin, and Shangbin Bai. 2025. "Spatial Reconfiguration of Living Stems and Snags Reveals Stand Structural Simplification During Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J.Houz.) Invasion into Coniferbroad-Leaf Forests" Plants 14, no. 11: 1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14111698

APA StyleChen, X., Zhou, X., Jin, S., & Bai, S. (2025). Spatial Reconfiguration of Living Stems and Snags Reveals Stand Structural Simplification During Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis (Carrière) J.Houz.) Invasion into Coniferbroad-Leaf Forests. Plants, 14(11), 1698. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14111698