Three Novel Biphenanthrene Derivatives and a New Phenylpropanoid Ester from Aerides multiflora and Their α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

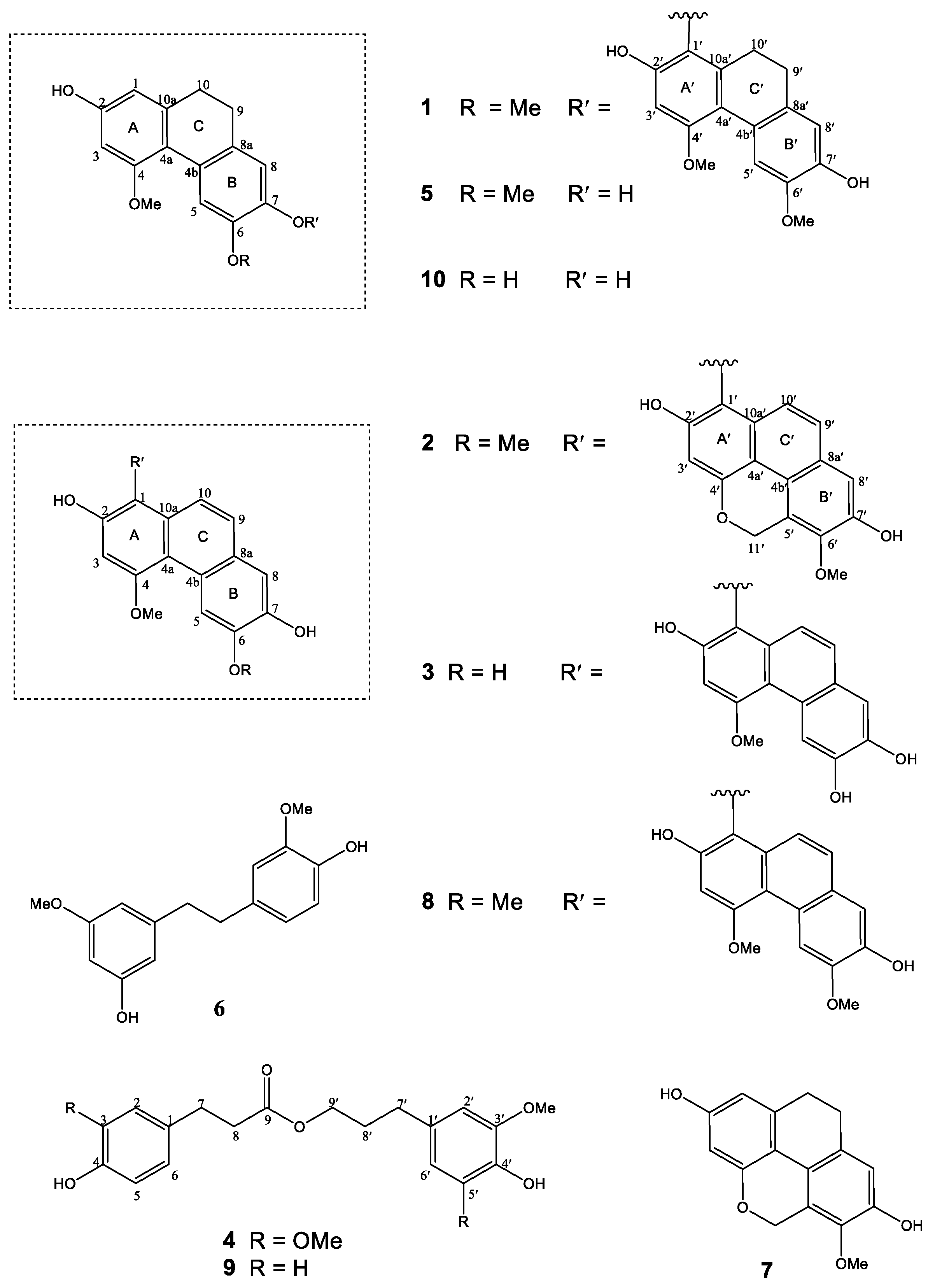

2.1. Structural Characterization

2.2. Chemotaxonomic Significance

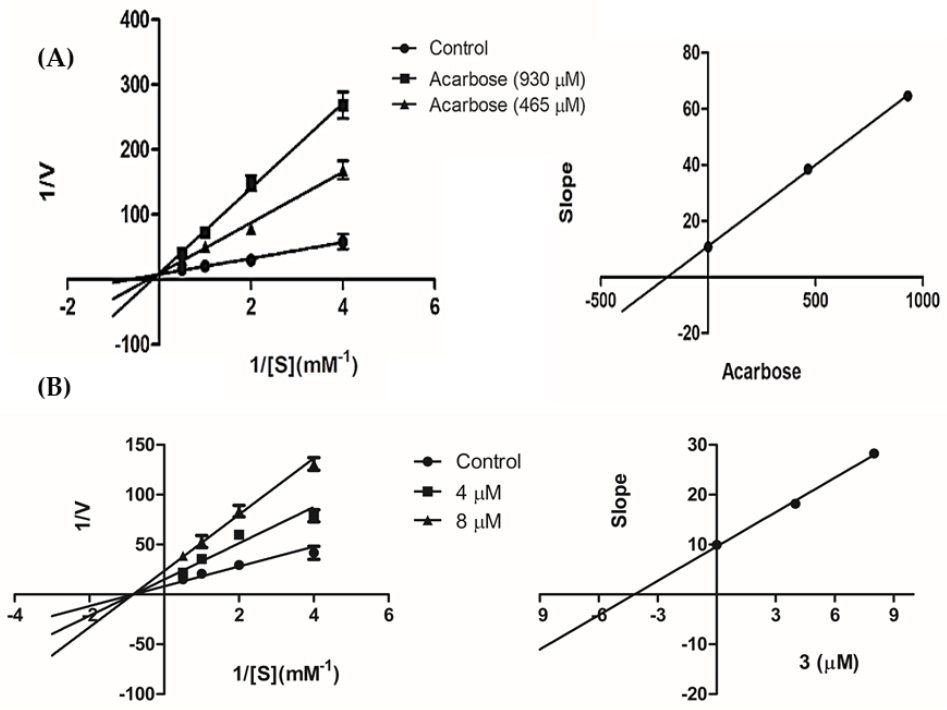

2.3. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

3.4. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karunaratne, V.; Thadhani, V.M.; Khan, S.N.; Choudhary, M.I. Potent α-glucosidase inhibitors from the lichen Cladonia species from Sri Lanka. J. Natl. Sci. Found Sri. 2014, 42, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, J.H.; Micha, R.; Imamura, F.; Pan, A.; Biggs, M.L.; Ajaz, O.; Mozaffarian, D. Omega-3 fatty acids and incident type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, S214–S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A.; Duvoor, C.; Reddy Dendi, V.S.; Kraleti, S.; Chada, A.; Ravilla, R.; Sasapu, A. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: Implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus management. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhiem, N.X.; Van Kiem, P.; Van Minh, C.; Ban, N.K.; Cuong, N.X.; Tung, N.H.; Kim, Y.H. α-glucosidase inhibition properties of cucurbitane-type triterpene glycosides from the fruits of Momordica charantia. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, T.M.; Mayer, D.A.; Siebert, D.A.; Micke, G.A.; Alberton, M.D.; Tavares, L.B.B.; De Oliveira, D. Kinetics analysis of the inhibitory effects of alpha-glucosidase and identification of compounds from Ganoderma lipsiense Mycelium. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, H.Y.; Qian, K.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Hsu, C.S.; Lee, K.H. Recent discovery of plant-derived anti-diabetic natural products. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 29, 580–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashiru, O.; Koh, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, D.S. Novel α-glucosidase from extreme thermophile Thermus caldophilus GK24. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001, 34, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ernawati, T.; Radji, M.; Hanafi, M.; Munim, A.; Yanuar, A. Cinnamic acid derivatives as α-glucosidase inhibitor agents. Indones. J. Chem. 2017, 17, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W. α-Glucosidase inhibitors isolated from medicinal plants. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2014, 3, 136–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.C.; Wu, P.C.; Wu, C.H.; Chen, L.K.; Chen, H.H.; Wu, M.S. Risk of liver injury after α-glucosidase inhibitor therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.S.; Prabuseenivasan, S.; Ignacimuthu, S. Cinnamaldehyde—A potential antidiabetic agent. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Qi, C.; Sun, W.; Shen, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. α-Glucosidase inhibitors from the coral-associated fungus Aspergillus terreus. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpanit, R.; Chuanasa, T.; Likhitwitayawuid, K.; Jongbunprasert, V.; Sritularak, B. α-Glucosidase inhibitors from Dendrobium tortile. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2016, 10, 609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhan, R.; Chen, Y. A new phenanthrene and a new 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene from Bulbophyllum retusiusculum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2447–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auberon, F.; Olatunji, O.J.; Waffo-Teguo, P.; Adekoya, A.E.; Bonte, F.; Merillon, J.M.; Lobstein, A. New glucosyloxybenzyl 2R-benzylmalate derivatives from the underground parts of Arundina graminifolia (Orchidaceae). Fitoterapia 2019, 135, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocyan, A.; de Vogel, E.F.; Conti, E.; Gravendeel, B. Molecular phylogeny of Aerides (Orchidaceae) based on one nuclear and two plastid markers: A step forward in understanding the evolution of the Aeridinae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 48, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant, B. Medicinal orchids and their uses: Tissue culture a potential alternative for conservation. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 7, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Huda, M.K.; Hoque, M.M. Investigation of secondary metabolites of nine medicinally important orchids of Bangladesh. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 602–606. [Google Scholar]

- Cakova, V.; Urbain, A.; Antheaume, C.; Rimlinger, N.; Wehrung, P.; Bonté, F.; Lobstein, A. Identification of phenanthrene derivatives in Aerides rosea (Orchidaceae) using the combined systems HPLC–ESI–HRMS/MS and HPLC–DAD–MS–SPE–UV–NMR. Phytochem. Anal. 2015, 26, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, V.; Rao, N.P. Aeridin: A phenanthropyran from Aerides crispum. Phytochemistry 1998, 48, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, T.K.; Rahman, M.M. In vitro study of medicinally important orchid Aerides multiflora Roxb. from nodal and leaf explants. J. Pharmacog. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Choon, K.K. Management of the Pha Taem Protected Forest Complex to Promote Cooperation for Transboundary Biodiversity Conservation between Thailand, Cambodia and Laos Phase I; Kasetsart University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schuiteman, A.; Bonnet, P.; Svengsuksa, B.; Barthélémy, D. An annotated checklist of the Orchidaceae of Laos. Nord. J. Bot. 2008, 26, 257–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, A.; Kunwar, B.; Choi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Van Andel, T.; Chaudhary, R.P.; De Boer, H.J.; Gravendeel, B. Collection and trade of wild-harvested orchids in Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, K.; Das, R.; Yonzone, R. Present ecological status, diversity, distribution and cultural significance of the genus Aerides Loureiro (Orchidaceae) in Tinsukia District (Assam) of North East India. J. Environ. Ecol. 2012, 30, 649–651. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.N. Medicinal orchid wealth of Arunachal Pradesh. Indian Med. Plants 2004, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanaksh, A.; Kaushik, P. Antibacterial effect of Aerides multiflora: A study in vitro. J. Orchid Soc. India 1999, 1, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Inthongkaew, P.; Chatsumpun, N.; Supasuteekul, C.; Kitisripanya, T.; Putalun, W.; Likhitwitayawuid, K.; Sritularak, B. α-Glucosidase and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activities and glucose uptake stimulatory effect of phenolic compounds from Dendrobium formosum. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2017, 27, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarakulwattana, C.; Mekboonsonglarp, W.; Likhitwitayawuid, K.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Sritularak, B. New bisbibenzyl and phenanthrene derivatives from Dendrobium scabrilingue and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 1694–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thant, M.T.; Chatsumpun, N.; Mekboonsonglarp, W.; Sritularak, B.; Likhitwitayawuid, K. New fluorene derivatives from Dendrobium gibsonii and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.W.; Kang, C.C.; Harrison, L.J.; Powell, A.D. Phenanthrenes, dihydrophenanthrenes and bibenzyls from the orchid Bulbophyllum vaginatum. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, H.; Qing, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Cytotoxic phenolics from Bulbophyllum odoratissimum. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmler, C.; Antheaume, C.; Lobstein, A. Antioxidant biomarkers from Vanda coerulea stems reduce irradiated HaCaT PGE-2 production as a result of COX-2 inhibition. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, P.L.; Banerjee, S.; Lahiri, S.; Mukhoti, N.; Sen, S. Dimeric phenanthrenes from two Agrostophyllum species. Phytochemistry 1998, 47, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Wang, N.; Yao, X. Phenolic components from Dendrobium nobile. Zhong Cao Yao 2006, 37, 652–655. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Y.W.; Kang, C.C.; Harrison, L.J.; Powell, A.D. Phenanthrene and other aromatic constituents of Bulbophyllum vaginatum. Phytochemistry 1998, 50, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, S.; Toscano, R.A.; Mata, R. New Phenanthrene derivatives from Maxillaria densa. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P.L.; Sabzabadi, E. Agrostophyllin, a naturally occurring phenanthropyran derivative from Agrostophyllum khasiyanum. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 1899–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yin, Q.M.; Zhang, X.W.; Wang, W.; Dong, X.Y.; Yan, X.; Hu, R. Bioactivity−guided isolation of biphenanthrenes from Liparis nervosa. Fitoterapia 2016, 115, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.J.; Kim, J.H.; Campbell, B.C.; Chou, S.C. Fungicidal activities of dihydroferulic acid alkyl ester analogues. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, J.X.; Wang, Y.H.; Su, X.L.; Mei, R.Q.; Yang, J.; Kong, Y.; Long, C.L. Neolignans from Selaginella moellendorffii. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2016, 6, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibout, R.; Le Bris, P.; Legee, F.; Cezard, L.; Renault, H.; Lapierre, C. Structural redesigning Arabidopsis lignins into alkali-soluble lignins through the expression of p-coumaroyl-CoA: Monolignol transferase PMT. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Q.; Liu, K.W.; Chen, L.J.; Xiao, X.J.; Zhai, J.W.; Li, L.Q.; Liu, Z.J. A new molecular phylogeny and a new genus, Pendulorchis, of the Aerides–Vanda alliance (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.X.; Li, Z.H.; Schuiteman, A.; Chase, M.W.; Li, J.W.; Huang, W.C.; Hidayat, A.; Wu, S.S.; Jin, X.H. Phylogenomics of Orchidaceae based on plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 139, 106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucca, D.L.; Sa, G.P.; Polastri, L.R.; Ghiraldi, D.M.; Ferreira, N.P.; Chiavelli, L.U.; Pomini, A.M. Biphenanthrene from Stanhopea lietzei (Orchidaceae) and its chemophenetic significance within neotropical species of the Cymbidieae tribe. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 89, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.D.; Jiang, F.S.; Yu, H.S.; Shen, Y.; Fu, Y.H.; Cheng, D.Q.; Ding, Z.S. Antibacterial Biphenanthrenes from the fibrous roots of Bletilla striata. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.L.; Kitanaka, S.; Liu, H.W.; Yao, X.S. New stilbenoids from Pholidota yunnanensis and their inhibitory effects on nitric oxide production. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 54, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, H.; Qing, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Two new biphenanthrenes with cytotoxic activity from Bulbophyllum odoratissimum. Fitoterapia 2009, 80, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.N.; Zhong, L.Y.; Bligh, S.A.; Guo, Y.L.; Zhang, C.F.; Zhang, M.; Xu, L.S. Bi-bicyclic and bi-tricyclic compounds from Dendrobium thyrsiflorum. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cai, L.; Tai, Z.; Zeng, X.; Ding, Z. Four new phenanthrenes from Monomeria barbata Lindl. Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, J.; Zeng, K.W.; Jiang, Y.; Tu, P.F. Five new biphenanthrenes from Cremastra appendiculata. Molecules 2016, 21, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auberon, F.; Olatunji, O.J.; Herbette, G.; Raminoson, D.; Antheaume, C.; Soengas, B.; Lobstein, A. Chemical constituents from the aerial parts of Cyrtopodium paniculatum. Molecules 2016, 21, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shao, S.Y.; Han, S.W.; Li, S. Atropisomeric bi (9, 10-dihydro) phenanthrene and phenanthrene/bibenzyl dimers with cytotoxic activity from the pseudobulbs of Pleione bulbocodioides. Fitoterapia 2019, 138, 104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auberon, F.; Olatunji, O.J.; Krisa, S.; Antheaume, C.; Herbette, G.; Bonté, F.; Lobstein, A. Two new stilbenoids from the aerial parts of Arundina graminifolia (Orchidaceae). Molecules 2016, 21, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. A new 9, 10-dihydrophenanthropyran dimer and a new natural 9, 10-dihydrophenanthropyran from Otochilus porrectus. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P.L.; Banerjee, S. Structure of flavanthrin, the first dimeric 9, 10-dihydrophenanthrene derivative from the orchid Eria flava. Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 7303–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchinda, P.; Udchachon, J.; Khumtaveeporn, K.; Taylor, W.C.; Engelhardt, L.M.; White, A.H. Phenanthrenes of Eulophia nuda. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 3267–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P.L.; Pal, A.; Joardar, M. Cirrhopetalanthrin, a dimeric phenanthrene derivative from the orchid Cirrhopetalum maculosum. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Chang, F.R.; Yen, M.H.; Yu, D.; Liu, Y.N.; Bastow, K.F.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Wu, Y.C.; Lee, K.S. Cytotoxic phenanthrenequinones and 9,10-dihydrophenanthrenes from Calanthe arisanensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, P.L.; Lahiri, S. Volucrin, a new dimeric phenanthrene derivative from the orchid Lusia volucris. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 3621–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.M.P.; Gonzalez, A.M.N.; Baez, E.G.; Diaz, S.L. Studies on the constituents of bulbs of the orchid Prosthechea michuacana and antioxidant activity. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2010, 46, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Liu, J.; Su, X.H.; Yuan, Z.P.; Zhong, Y.J.; Li, Y.F.; Liang, B. New dimeric phenanthrene and flavone from Spiranthes sinensis. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 15, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Morikawa, T.; Xie, H.; Yoshikawa, M. Antiallergic phenanthrenes and stilbenes from the tubers of Gymnadenia conopsea. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Xue, Q.; Zhu, S.; Sun, J.; Liu, W.; Ding, X. The complete plastome sequences of four orchid species: Insights into the evolution of the Orchidaceae and the utility of plastomic mutational hotspots. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawati, T. In silico evaluation of molecular interactions between known α-glucosidase inhibitors and homologous α-glucosidase enzymes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rattus norvegicus and GANC-human. Thai J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanawansa, R.; Faridmoayer, A.; van der Merwe, G.; Li, Y.X.; Scaman, C.H. Overexpression, purification, and partial characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae processing alpha glucosidase I. J. Glycobiol. 2002, 12, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liu, J.L.; Kong, Y.C.; Miao, J.Y.; Mei, X.Y.; Wu, S.Y.; Yan, Y.C.; Cao, X.Y. Spectroscopy and molecular docking analysis reveal structural specificity of flavonoids in the inhibition of α-glucosidase activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Ramírez, D.; Pereda-Miranda, R.; Escandón-Rivera, S.; Arreguín-Espinosa, R. Identification of α-glucosidase inhibitors from Ipomoea alba by affinity-directed fractionation-mass spectrometry. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2020, 30, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kongstad, K.T.; Liu, Y.; He, C.; Staerk, D. Unraveling the complexity of complex mixtures by combining high-resolution pharmacological, analytical and spectroscopic techniques: Antidiabetic constituents in Chinese medicinal plants. Faraday Discuss. 2019, 218, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proença, C.; Freitas, M.; Ribeiro, D.; Oliveira, E.F.; Sousa, J.L.; Tomé, S.M.; Fernandes, E. α-glucosidase inhibition by flavonoids: An in vitro and in silico structure–activity relationship study. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San, H.T.; Boonsnongcheep, P.; Putalun, W.; Mekboonsonglarp, W.; Sritularak, B.; Likhitwitayawuid, K. α-glucosidase inhibitory and glucose uptake stimulatory effects of phenolic compounds from Dendrobium christyanum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougale, A.D.; Ghadyale, V.A.; Panaskar, S.N.; Arvindekar, A.U. Alpha glucosidase inhibition by stem extract of Tinospora cordifolia. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadyale, V.; Takalikar, S.; Haldavnekar, V.; Arvindekar, A. Effective control of postprandial glucose level through inhibition of intestinal alpha glucosidase by Cymbopogon martinii (Roxb.). Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatsumpun, N.; Sritularak, B.; Likhitwitayawuid, K. New biflavonoids with α-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activities from Boesenbergia rotunda. Molecules 2017, 22, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Position | 1 a | 5 b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (Multiplicity, J in Hz) | δC | HMBC (Correlation with 1H) | δH (Multiplicity, J in Hz) | δC | |

| 1 | 6.35 (d, J = 2.5 Hz) | 108.3 | 3, 10, HO-2 | 6.39 (br s) | 107.4 |

| 2 | - | 157.8 | 1 *, 3 *, HO-2 * | - | 156.5 |

| 3 | 6.46 (d, J = 2.5 Hz) | 99.1 | 1, HO-2 | 6.65 (br s) | 98.3 |

| 4 | - | 158.8 | 3 *, MeO-4 | - | 157.7 |

| 4a | - | 115.9 | 1, 3, 5, 10 | - | 115.5 |

| 4b | - | 127.8 | 5 *, 8, 9 | - | 124.7 |

| 5 | 7.98 (s) | 114.3 | - | 7.89 (s) | 112.2 |

| 6 | - | 147.4 | 8, MeO-6 | - | 145.1 |

| 7 | - | 146.6 | 5 | - | 144.3 |

| 8 | 6.33 (s) | 113.6 | 9 | 6.69 (s) | 114.0 |

| 8a | - | 131.1 | 5, 10 | - | 130.7 |

| 9 | 2.45 (m) | 29.0 | 8 | 2.61 (m) | 28.9 |

| 10 | 2.56 (m) | 31.4 | 1 | 2.61 (m) | 30.7 |

| 10a | - | 141.6 | 9, 10 * | - | 140.5 |

| 1′ | - | 133.7 | 3′, 10′, HO-2′ | ||

| 2′ | - | 149.8 | 3′ *, HO-2′ * | ||

| 3′ | 6.65 (s) | 100.2 | HO-2′ | ||

| 4′ | - | 155.3 | 3′ *, MeO-4′ | ||

| 4a′ | - | 117.1 | 3′, 5′, 10′ | ||

| 4b′ | - | 125.2 | 5′ *, 8′, 9′ | ||

| 5′ | 7.93 (s) | 113.4 | - | ||

| 6′ | - | 146.1 | 8′, MeO-6′, HO-7′ | ||

| 7′ | - | 145.6 | 5′, HO-7′ * | ||

| 8′ | 6.66 (s) | 114.9 | 9′, HO-7′ | ||

| 8a′ | - | 131.4 | 5′, 10′ | ||

| 9′ | 2.52 (br s) | 29.9 | 8′ | ||

| 10′ | 2.52 (br s) | 24.1 | - | ||

| 10a′ | - | 133.8 | 9′ | ||

| MeO-4 | 3.89 (s) | 56.1 | - | 3.86 (s) | 55.5 |

| MeO-6 | 3.92 (s) | 56.5 | - | 3.83 (s) | 54.9 |

| MeO-4′ | 3.91 (s) | 56.4 | - | ||

| MeO-6′ | 3.84 (s) | 55.8 | - | ||

| HO-2 | 8.35 (s) | - | - | ||

| HO-2′ | 8.25 (s) | - | - | ||

| HO-7′ | 7.44 (s) | - | - |

| Position | 2 a | 3 b | 8 b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (Multiplicity, J in Hz) | δC | HMBC (Correlation with 1H) | δH (Multiplicity, J in Hz) | δC | HMBC (Correlation with 1H) | δH (Multiplicity, J in Hz) | δC | |

| 1 | - | 109.3 | 3, 10 | - | 108.8 | 3, 10, HO-2 | - | 108.9 |

| 2 | - | 155.0 | 3 * | - | 154.1 | 3 *, HO-2 * | - | 154.2 |

| 3 | 6.99 (s) | 100.0 | - | 6.95 (s) | 98.8 | HO-2 | 7.00 (s) | 99.2 |

| 4 | - | 160.2 | 3 *, MeO-4 | - | 159.4 | 3 *, MeO-4 | - | 159.3 |

| 4a | - | 116.2 | 3, 5, 10 | - | 115.1 | 3, 5, 10 | - | 115.5 |

| 4b | - | 125.8 | 8, 9 | - | 125.3 | 8, 9 | - | 124.9 |

| 5 | 9.24 (s) | 109.8 | - | 9.19 (s) | 112.7 | - | 9.26 (s) | 111.3 |

| 6 | - | 148.5 | 5 *, 8, MeO-6 | - | 145.3 | 8 | - | 147.6 |

| 7 | - | 146.0 | 5, 8 * | - | 144.1 | 5 | - | 145.2 |

| 8 | 7.19 (s) | 112.2 | 9 | 7.19 (s) | 111.5 | 9 | 7.20 (s) | 112.3 |

| 8a | - | 128.0 | 5, 10 | - | 126.7 | 5, 10 | - | 127.2 |

| 9 | 7.36 (d, J = 9.5 Hz) | 126.5 | 8 | 7.31 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 127.2 | 8 | 7.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 127.1 |

| 10 | 6.98 (d, J = 9.5 Hz) | 123.3 | - | 6.87 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 121.8 | - | 6.95 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 122.5 |

| 10a | - | 135.4 | 9 | - | 134.6 | 9 | - | 134.6 |

| 1′ | - | 110.2 | 3′, 10′ | - | 108.8 | 3′, 10′, HO-2′ | - | 108.9 |

| 2′ | - | 156.3 | 3′ * | - | 154.1 | 3′ *, HO-2′ * | - | 154.2 |

| 3′ | 6.81 (s) | 103.1 | - | 6.95 (s) | 98.8 | HO-2′ | 7.00 (s) | 99.2 |

| 4′ | - | 153.7 | 3′ *, 11′ | - | 159.4 | 3′ *, MeO-4′ | - | 159.3 |

| 4a′ | - | 113.0 | 3′, 10′ | - | 115.1 | 3′, 5′, 10′ | - | 115.5 |

| 4b′ | - | 119.1 | 8′, 9′, 11′ | - | 125.3 | 8′, 9′ | - | 124.9 |

| 5′ | - | 120.6 | 11′ * | 9.19 (s) | 112.7 | - | 9.26 (s) | 111.3 |

| 6′ | - | 144.2 | 8′, 11′, MeO-6′ | - | 145.3 | 8′ | - | 147.6 |

| 7′ | - | 150.3 | 8′ * | - | 144.1 | 5′ | - | 145.2 |

| 8′ | 7.21 (s) | 111.6 | 9′ | 7.19 (s) | 111.5 | 9′ | 7.20 (s) | 112.3 |

| 8a′ | - | 126.2 | 10′ | - | 126.7 | 5′, 10′ | - | 127.2 |

| 9′ | 7.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 127.9 | 8′ | 7.31 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 127.2 | 8′ | 7.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 127.1 |

| 10′ | 6.92 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 124.6 | - | 6.87 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 121.8 | - | 6.95 (d, J = 9.0 Hz) | 122.5 |

| 10a′ | - | 132.2 | 9′ | - | 134.6 | 9′ | - | 134.6 |

| 11′ | 5.79 (d, J = 1.5 Hz) | 64.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MeO-4 | 4.22 (s) | 56.1 | - | 4.18 (s) | 55.0 | 4.24 (s) | 55.3 | |

| MeO-6 | 4.06 (s) | 56.0 | - | - | - | 4.08 (s) | 55.2 | |

| MeO-4′ | - | - | - | 4.18 (s) | 55.0 | 4.24 (s) | 55.3 | |

| MeO-6′ | 3.95 (s) | 61.3 | - | - | - | 4.08 (s) | 55.2 | |

| HO-2 | - | - | - | 7.54 (s) | - | 7.61 (s) | - | |

| HO-2′ | - | - | - | 7.54 (s) | - | 7.61 (s) | - | |

| Position | δH (Multiplicity, J in Hz) | δC | HMBC (Correlation with 1H) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 132.1 | 5, 7 *, 8 |

| 2 | 6.85 (d, J = 1.5 Hz) | 111.8 | 6, 7 |

| 3 | - | 147.3 | 5, MeO-3, HO-4 |

| 4 | - | 144.9 | 2, 6, HO-4 * |

| 5 | 6.73 (d, J = 8.1 Hz) | 114.8 | HO-4 |

| 6 | 6.68 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz) | 120.6 | 2, 7 |

| 7 | 2.81 (m) | 30.4 | 2, 6, 8 * |

| 8 | 2.59 (t, J = 7.5 Hz) | 35.8 | 7 * |

| 9 | - | 172.2 | 7, 8 *, 9′ |

| 1′ | - | 131.7 | 8′ |

| 2′ | 6.49 (s) | 105.8 | 6′, 7′ |

| 3′ | - | 147.7 | 2′ *, HO-4′, MeO-3′ |

| 4′ | - | 134.2 | 2′, 6′, HO-4′ * |

| 5′ | - | 147.7 | 6′ *, HO-4′, MeO-5′ |

| 6′ | 6.49 (s) | 105.8 | 2′, 7′ |

| 7′ | 2.57 (t, J = 7.5 Hz) | 31.8 | 2′, 6′, 8′ *, 9′ |

| 8′ | 1.89 (m) | 30.4 | 7′ *, 9′ * |

| 9′ | 4.05 (t, J = 7.5 Hz) | 63.2 | 7′, 8′ * |

| MeO-3 | 3.82 (s) | 55.3 | - |

| MeO-3′ | 3.80 (s) | 55.7 | - |

| MeO-5′ | 3.80 (s) | 55.7 | - |

| HO-4 | 7.35 (s) | - | - |

| HO-4′ | 6.94 (s) | - | - |

| Compounds | IC50 (μg/mL) | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Aerimultin A (1) | 16.8 ± 1.0 | 30.9 ± 1.9 |

| Aerimultin B (2) | 41.8 ± 1.3 | 77 ± 2.5 |

| Aerimultin C (3) | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.7 |

| Dihydrosinapyl dihydroferulate (4) | NA | NA |

| 6-Methoxy coelonin (5) | 61.2 ± 2.2 | 224.8 ± 7.8 |

| Gigantol (6) | 52.5 ± 1.9 | 191.3 ± 6.8 |

| Imbricatin (7) | 44.9 ± 2.1 | 165.9 ± 7.7 |

| Agrostonin (8) | 20.1 ± 2.5 | 37.2 ± 4.5 |

| Dihydroconiferyl dihydro-p-coumarate (9) | 88.1 ± 2.9 | 266.7 ± 8.6 |

| 5-Methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,3,7-triol (10) | 29.7 ± 2.3 | 115.2 ± 9.1 |

| Acarbose | 332.1 ± 5.9 | 514.4 ± 9.2 |

| Inhibitors | Dose (μM) | Vmax ∆OD/min | Km (mM) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | - | 0.10 | 1.22 | |

| 3 | 8 | 0.035 | 1.20 | 4.18 |

| 4 | 0.055 | 1.22 | ||

| Acarbose | 930 | 0.11 | 6.47 | 190.57 |

| 465 | 0.10 | 4.17 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thant, M.T.; Sritularak, B.; Chatsumpun, N.; Mekboonsonglarp, W.; Punpreuk, Y.; Likhitwitayawuid, K. Three Novel Biphenanthrene Derivatives and a New Phenylpropanoid Ester from Aerides multiflora and Their α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Plants 2021, 10, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020385

Thant MT, Sritularak B, Chatsumpun N, Mekboonsonglarp W, Punpreuk Y, Likhitwitayawuid K. Three Novel Biphenanthrene Derivatives and a New Phenylpropanoid Ester from Aerides multiflora and Their α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Plants. 2021; 10(2):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020385

Chicago/Turabian StyleThant, May Thazin, Boonchoo Sritularak, Nutputsorn Chatsumpun, Wanwimon Mekboonsonglarp, Yanyong Punpreuk, and Kittisak Likhitwitayawuid. 2021. "Three Novel Biphenanthrene Derivatives and a New Phenylpropanoid Ester from Aerides multiflora and Their α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity" Plants 10, no. 2: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020385

APA StyleThant, M. T., Sritularak, B., Chatsumpun, N., Mekboonsonglarp, W., Punpreuk, Y., & Likhitwitayawuid, K. (2021). Three Novel Biphenanthrene Derivatives and a New Phenylpropanoid Ester from Aerides multiflora and Their α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity. Plants, 10(2), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020385