Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols on Beta-Cell Function and Survival

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

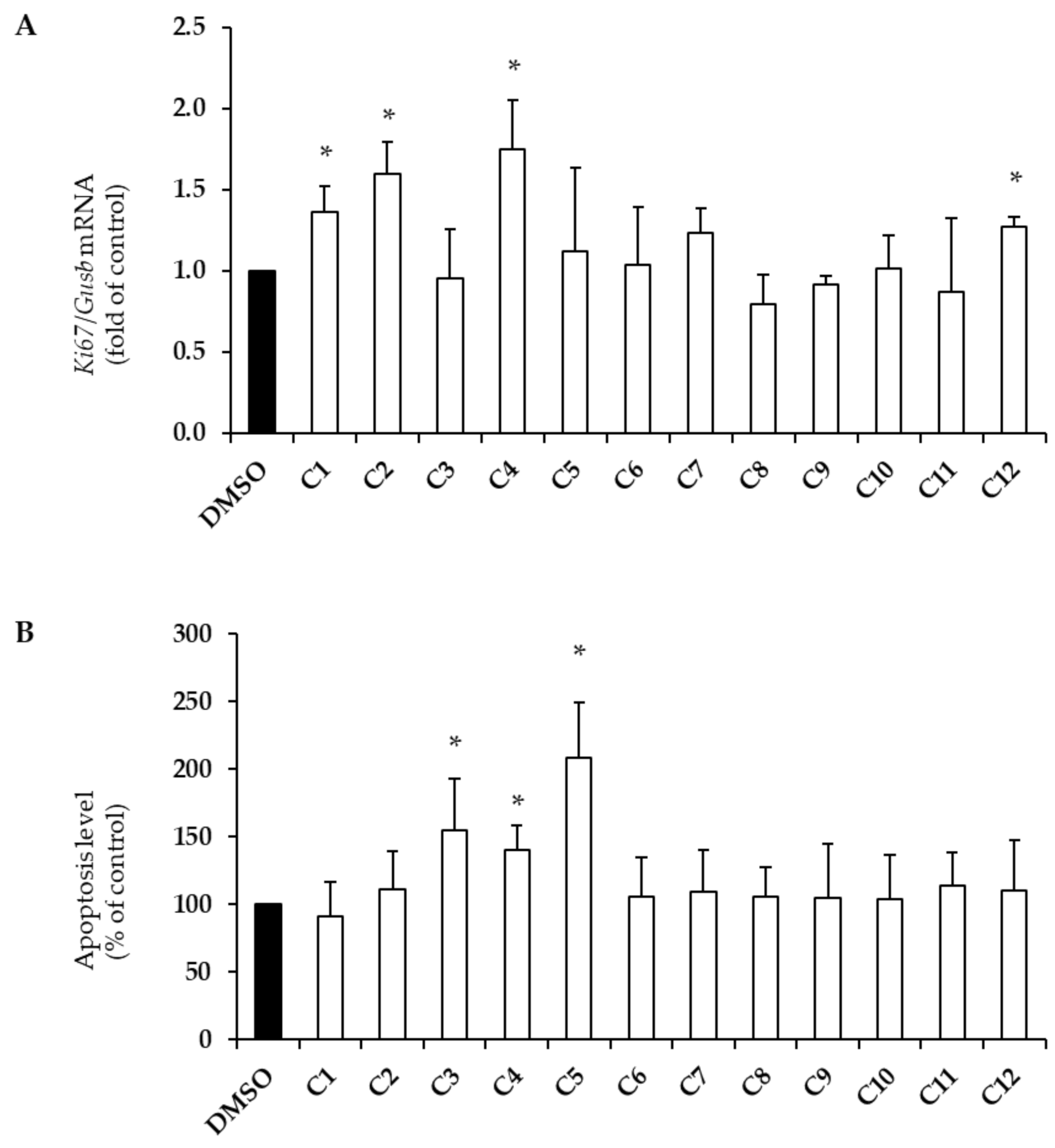

2.1. Effects of EVOO PCs on Beta-Cell Survival

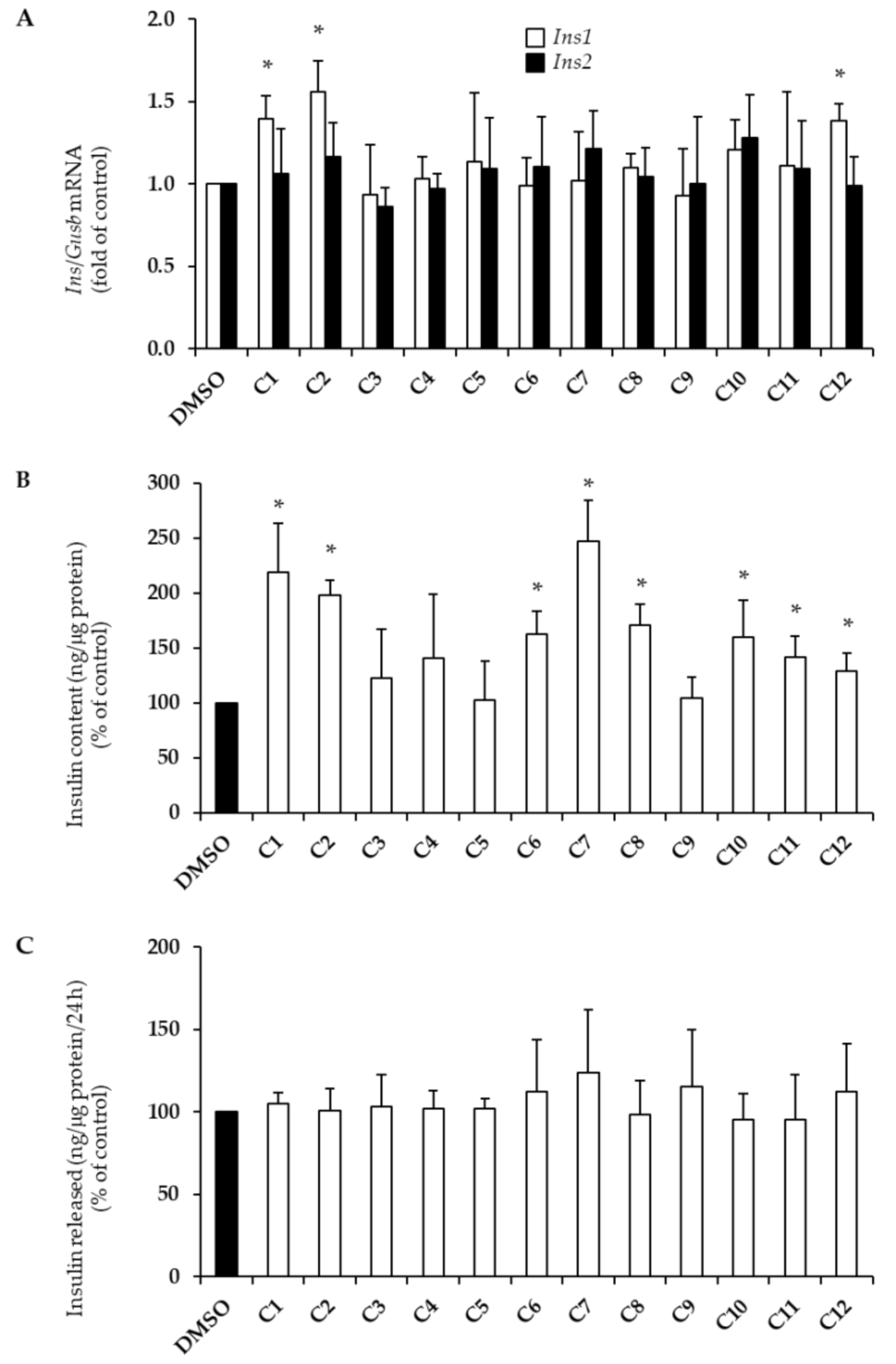

2.2. Effects of EVOO PCs on Insulin Biosynthesis

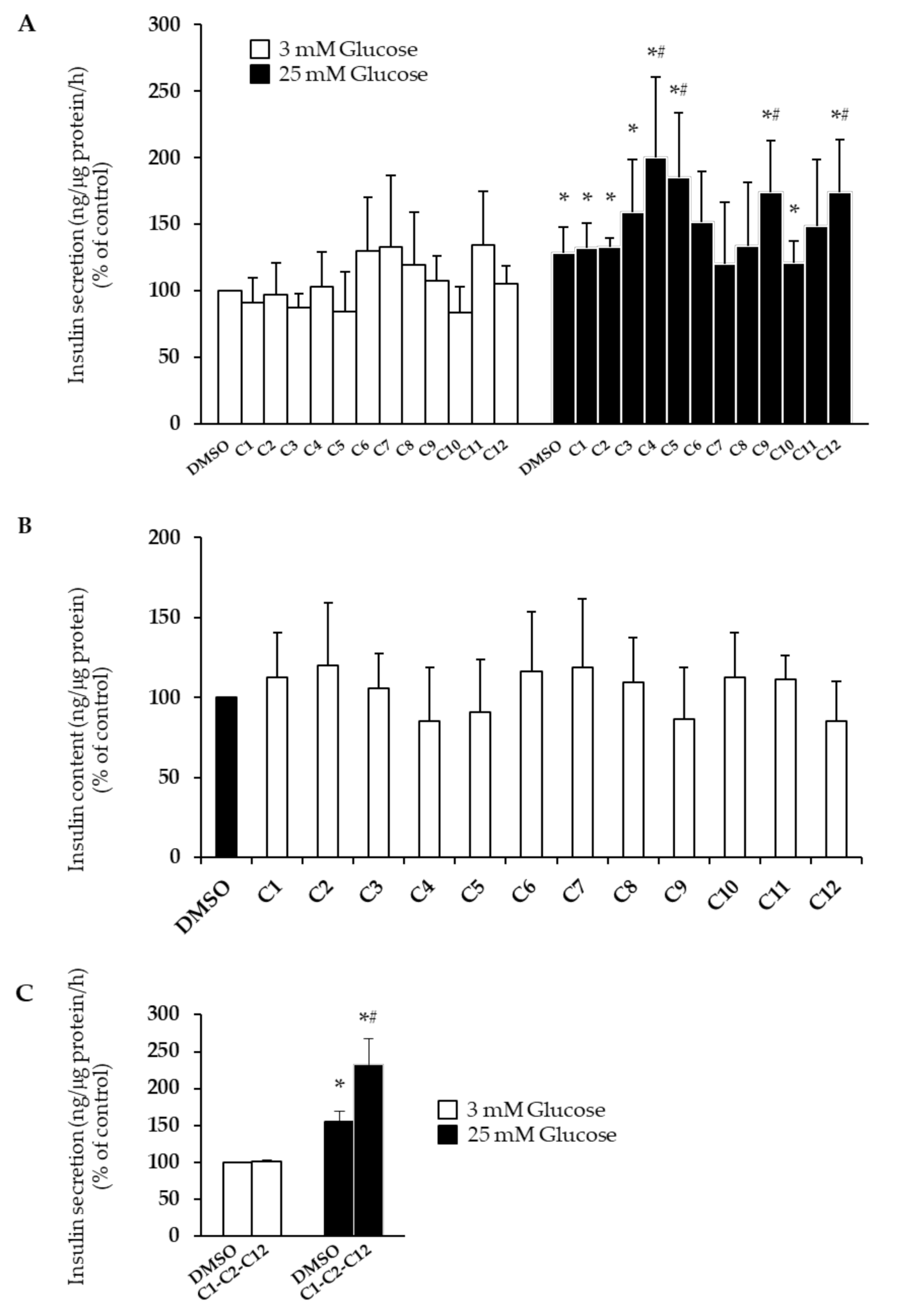

2.3. Effects of EVOO PCs on Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion

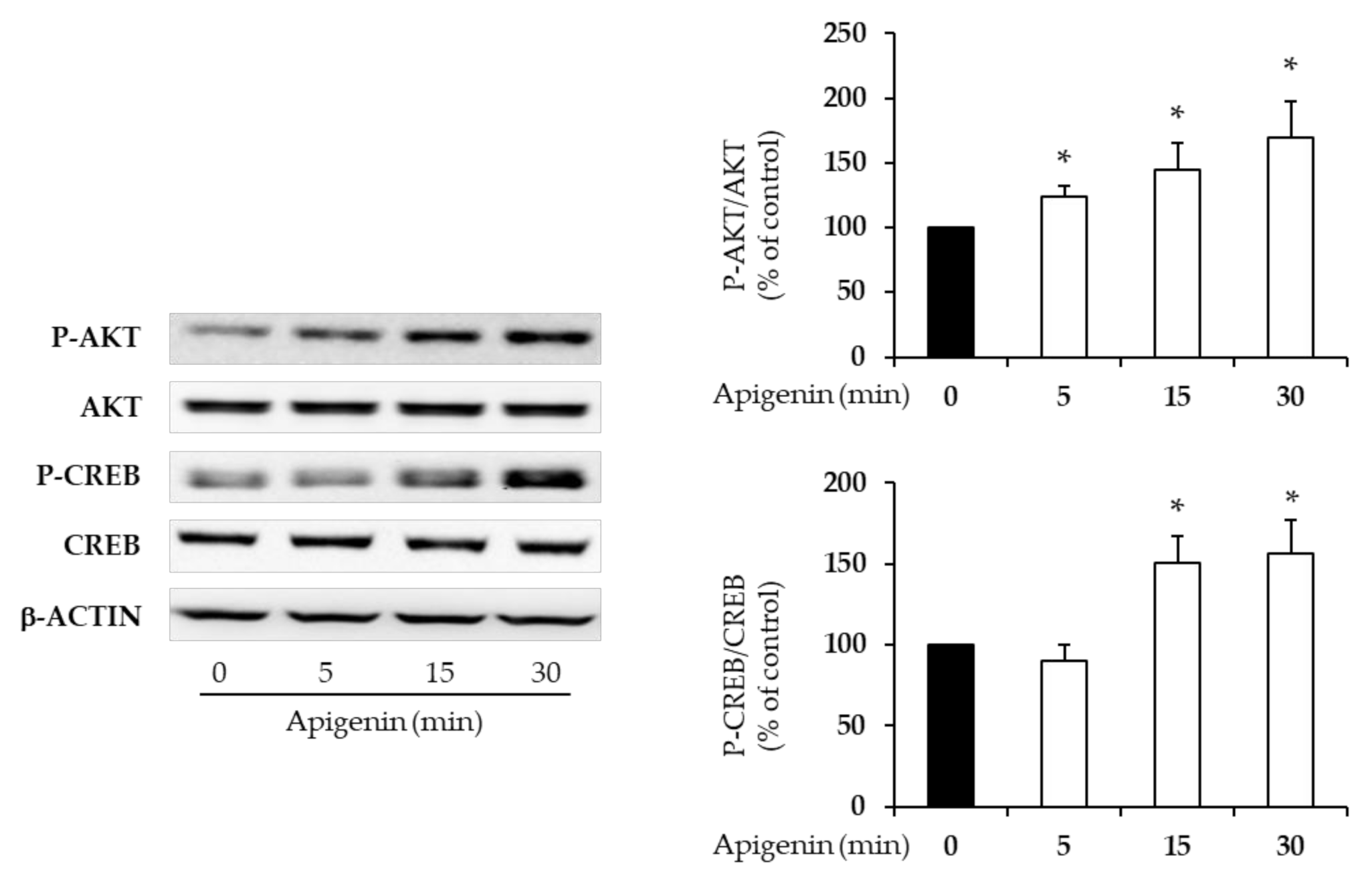

2.4. Apigenin Activates Beta-Cell Intracellular Signaling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Human Pancreatic Islets

4.3. Chemicals and Treatments

4.4. Immunoblotting and Measurement of Apoptosis

4.5. Gene Expression by Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.6. Measurement of Insulin Content and Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS)

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cho, N.; Shaw, J.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; Fernandes, J.D.R.; Ohlrogge, A.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrano, N.; Biondi, G.; Cignarelli, A.; Perrini, S.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F.; Natalicchio, A. Functional loss of pancreatic islets in type 2 diabetes: How can we halt it? Metabolism 2020, 154304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Fradkin, J.; Kernan, W.N.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G.; Rossing, P.; Tsapas, A.; Wexler, D.J.; Buse, J.B. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2669–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocchi, A.; Leone, L.; Agostoni, C.; Pali-Schöll, I. The Secrets of the Mediterranean Diet. Does [Only] Olive Oil Matter? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Bulló, M.; Babio, N.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Ibarrola-Jurado, N.; Basora, J.; Estruch, R.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; et al. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with the Mediterranean Diet: Results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2010, 34, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Salvadó, J.; Bulló, M.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Covas, M.-I.; Ibarrola-Jurado, N.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; et al. Prevention of Diabetes with Mediterranean Diets. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Korat, A.A.; Malik, V.; Hu, F.B. Metabolic Effects of Monounsaturated Fatty Acid–Enriched Diets Compared with Carbohydrate or Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid–Enriched Diets in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Strasser, B.; Hoffmann, G. Effects of Monounsaturated Fatty Acids on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 59, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Strasser, B. High-MUFA Diets Reduce Fasting Glucose in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 60, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, C.; Filesi, C.; Varì, R.; Scazzocchio, B.; Filardi, T.; Fogliano, V.; D’Archivio, M.; Giovannini, C.; Lenzi, A.; Morano, S.; et al. Consumption of extra-virgin olive oil rich in phenolic compounds improves metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A possible involvement of reduced levels of circulating visfatin. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedan, V.; Popp, M.; Rohn, S.; Nyfeler, M.; Bongartz, A. Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Their Contribution to Sensory Properties of Olive Oil. Molecules 2019, 24, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to olive oil and maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1316, 1332), maintenance of normal (fasting) blood concentrations of triglycerides (ID 1316, 1332), maintenan. EFSA J. 2011, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazi, L.; Rachdi, L.; Weiss, A.J.; Crasmeneur, C.; Bernalmizrachi, E. Regulation of β-cell mass and function by the Akt/protein kinase B signalling pathway. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2007, 9, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle, S.; Quoyer, J.; Varin, E.; Costes, S. Roles and Regulation of the Transcription Factor CREB in Pancreatic β-Cells. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 4, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Im, S.W.; Jung, C.H.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Ahn, J. Tyrosol, an olive oil polyphenol, inhibits ER stress-induced apoptosis in pancreatic β-cell through JNK signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Oksbjerg, N.; Young, J.F.; Jeppesen, P.B. Caffeic acid, naringenin and quercetin enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and glucose sensitivity in INS-1E cells. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2013, 16, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Metya, S.K.; Sannigrahi, S.; Rahaman, N.; Ahmed, F. Treatment with ferulic acid to rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes: Effects on oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and apoptosis in the pancreatic β cell. Endocrine 2013, 44, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sompong, W.; Cheng, H.; Adisakwattana, S. Ferulic acid prevents methylglyoxal-induced protein glycation, DNA damage, and apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 73, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shi, X.; Shuai, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, X.; Wei, D.; Su, D. Luteolin prevents uric acid-induced pancreatic b-cell dysfunction. J. Biomed. Res. 2014, 28, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-K.; Kwon, K.-B.; Song, M.-Y.; Han, M.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-R.; Lee, J.-H.; Ryu, D.-G.; Park, B.-H.; Park, J.-W. Flavonoids Protect Against Cytokine-Induced Pancreatic β-Cell Damage Through Suppression of Nuclear Factor κB Activation. Pancreas 2007, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; He, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wan, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, S.; Yao, X. Natural Product Luteolin Rescues THAP-Induced Pancreatic β-Cell Dysfunction through HNF4α Pathway. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaari, A. Inhibition of human islet amyloid polypeptide aggregation and cellular toxicity by oleuropein and derivatives from olive oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Velander, P.; Liu, D.; Xu, B. Olive Component Oleuropein Promotes β-Cell Insulin Secretion and Protects β-Cells from Amylin Amyloid-Induced Cytotoxicity. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 5035–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumaoğlu, A.; Ari, N.; Kartal, M.; Karasu, Ç.; Cumaoǧlu, A. Polyphenolic Extracts from Olea europea L. Protect Against Cytokine-Induced β-Cell Damage Through Maintenance of Redox Homeostasis. Rejuvenation Res. 2011, 14, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effects of Olive Leaf Polyphenols Against H₂O₂ Toxicity in Insulin Secreting β-Cells. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21383995/ (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- Wang, N.; Yi, W.J.; Tan, L.; Zhang, J.H.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Qin, M.; Yu, S.; Guan, J.; Zhang, R. Apigenin attenuates streptozotocin-induced pancreatic β cell damage by its protective effects on cellular antioxidant defense. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2017, 53, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.A.; Zohari, F.; Sadeghi, H. Antioxidant and Protective Effects of Major Flavonoids from Teucrium poliumon β-Cell Destruction in a Model of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K.S.; Oh, S.; Woo, J.-T.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, Y.S.; Chon, S. Apigenin attenuates 2-deoxy-D-ribose-induced oxidative cell damage in HIT-T15 pancreatic β-cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado-Ruiz, E.; Álvarez-Amor, L.; Varela, L.M.; Berná, G.; Parra-Camacho, M.S.; Oliveras-Lopez, M.J.; Martínez-Force, E.; Rojas, A.; Hmadcha, A.; Soria, B.; et al. Extra virgin olive oil diet intervention improves insulin resistance and islet performance in diet-induced diabetes in mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Cerretani, L.; Bendini, A.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Gallina-Toschi, T.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Analytical determination of polyphenols in olive oils. J. Sep. Sci. 2005, 28, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasteska, D.; Hodson, D.J. The role of beta cell heterogeneity in islet function and insulin release. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61, R43–R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, L.; Cicerale, S. The Health Benefiting Mechanisms of Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds. Molecules 2016, 21, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vissers, M.N.; Zock, P.L.; Katan, M.B. Bioavailability and antioxidant effects of olive oil phenols in humans: A review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, M.; Valls, R.M.; Romero, M.-P.; Macià, A.; Fernández, S.; Giralt, M.; Solà, R.; Motilva, M.-J. Bioavailability of phenols from a phenol-enriched olive oil. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Code |

|---|---|

| Hydroxytyrosol | C1 |

| Tyrosol | C2 |

| Caffeic acid | C3 |

| Vanillic acid | C4 |

| Vanillin | C5 |

| p-Coumaric acid | C6 |

| Ferulic acid | C7 |

| Sinapic acid | C8 |

| Luteolin | C9 |

| (+)-Pinoresinol | C10 |

| Oleuropein | C11 |

| Apigenin | C12 |

| Compound | Proliferation | Apoptosis | Insulin1 mRNA Level | Insulin Content | GSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxytyrosol | ↑ | - | ↑ | ↑ | - |

| Tyrosol | ↑ | - | ↑ | ↑ | - |

| Caffeic acid | - | ↑ | - | - | - |

| Vanillic acid | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | ↑ |

| Vanillin | - | ↑ | - | - | ↑ |

| p-Coumaric acid | - | - | - | ↑ | ↓ |

| Ferulic acid | - | - | - | ↑ | ↓ |

| Sinapic acid | - | - | - | ↑ | ↓ |

| Luteolin | - | - | - | - | ↑ |

| (+)-Pinoresinol | - | - | - | ↑ | - |

| Oleuropein | - | - | - | ↑ | ↓ |

| Apigenin | ↑ | - | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Age (years) | Sex | BMI (kg/m2) | FPG (mg/dL) | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islet preparation 1 | 66 | F | 19.38 | 82 | dpc |

| Islet preparation 2 | 64 | F | 22.43 | 93 | dpc |

| Islet preparation 3 | 61 | M | 18.38 | 82 | dpc |

| Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| rattus_ Insulin1 (Ins1) | CTGCCCAGGCTTTTGTCAA | Forward |

| rattus_ Insulin1 (Ins1) | TCCCCACACACCAGGTACAGA | Reverse |

| rattus_ Insulin2 (Ins2) | GCAAGCAGGTCATTGTTCCA | Forward |

| rattus_ Insulin2 (Ins2) | GGTGCTGTTTGACAAAAGCC | Reverse |

| rattus_ Mki67 | GGACCCCAAAGAAGTGTTGA | Forward |

| rattus_ Mki67 | GCTTCTCACCTGTTGCTTCC | Reverse |

| rattus_ Gusb | GACGTTGGGCTGGTGAACTAC | Forward |

| rattus_ Gusb | CACGGGCCACAATTTTGC | Reverse |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marrano, N.; Spagnuolo, R.; Biondi, G.; Cignarelli, A.; Perrini, S.; Vincenti, L.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F.; Natalicchio, A. Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols on Beta-Cell Function and Survival. Plants 2021, 10, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020286

Marrano N, Spagnuolo R, Biondi G, Cignarelli A, Perrini S, Vincenti L, Laviola L, Giorgino F, Natalicchio A. Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols on Beta-Cell Function and Survival. Plants. 2021; 10(2):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020286

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarrano, Nicola, Rosaria Spagnuolo, Giuseppina Biondi, Angelo Cignarelli, Sebastio Perrini, Leonardo Vincenti, Luigi Laviola, Francesco Giorgino, and Annalisa Natalicchio. 2021. "Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols on Beta-Cell Function and Survival" Plants 10, no. 2: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020286

APA StyleMarrano, N., Spagnuolo, R., Biondi, G., Cignarelli, A., Perrini, S., Vincenti, L., Laviola, L., Giorgino, F., & Natalicchio, A. (2021). Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols on Beta-Cell Function and Survival. Plants, 10(2), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020286