Hierarchical Semantic Correspondence Analysis on Feature Classes between Two Geospatial Datasets Using a Graph Embedding Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Laplacian Graph Embedding

2.1. One-dimensional Embedding

2.2. k-dimensional Embedding

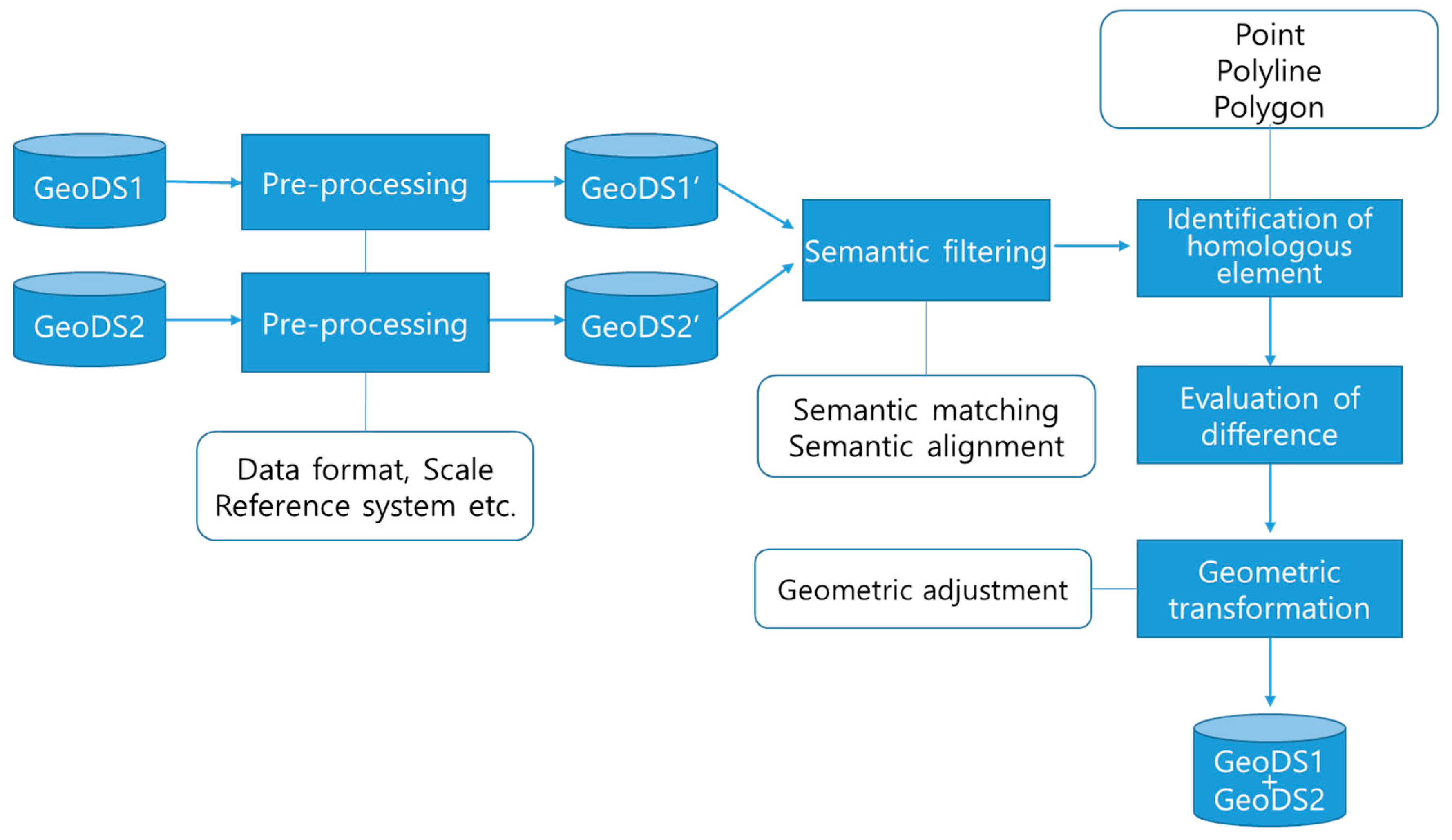

3. Proposed Method

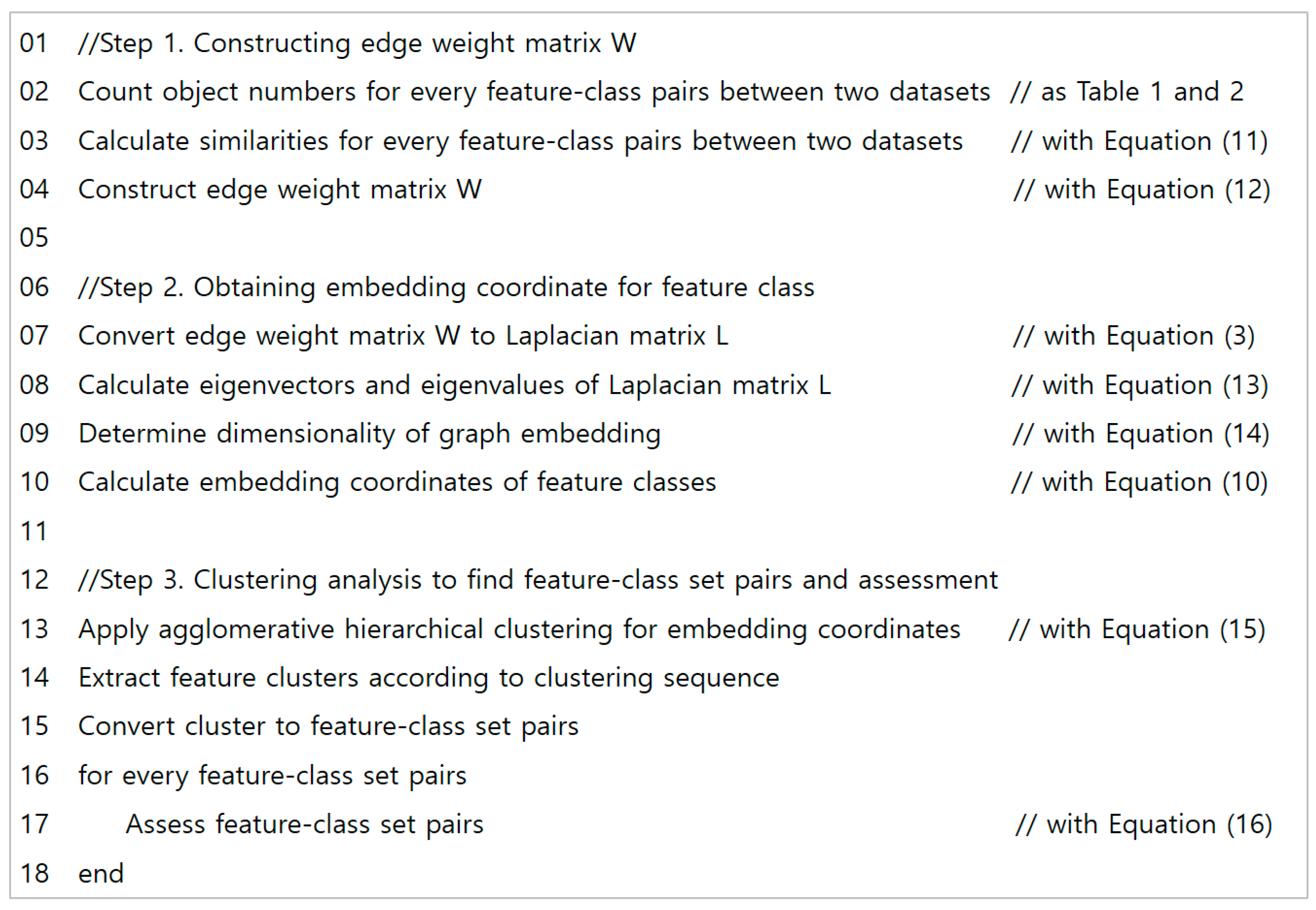

3.1. Step 1: Constructing Edge Weight Matrix W

3.2. Step 2: Solving Eigenproblem and Obtaining K-dimensional Coordinates

3.3. Step 3: Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering Analysis and Assessment of Clusters

4. Experiment and Results

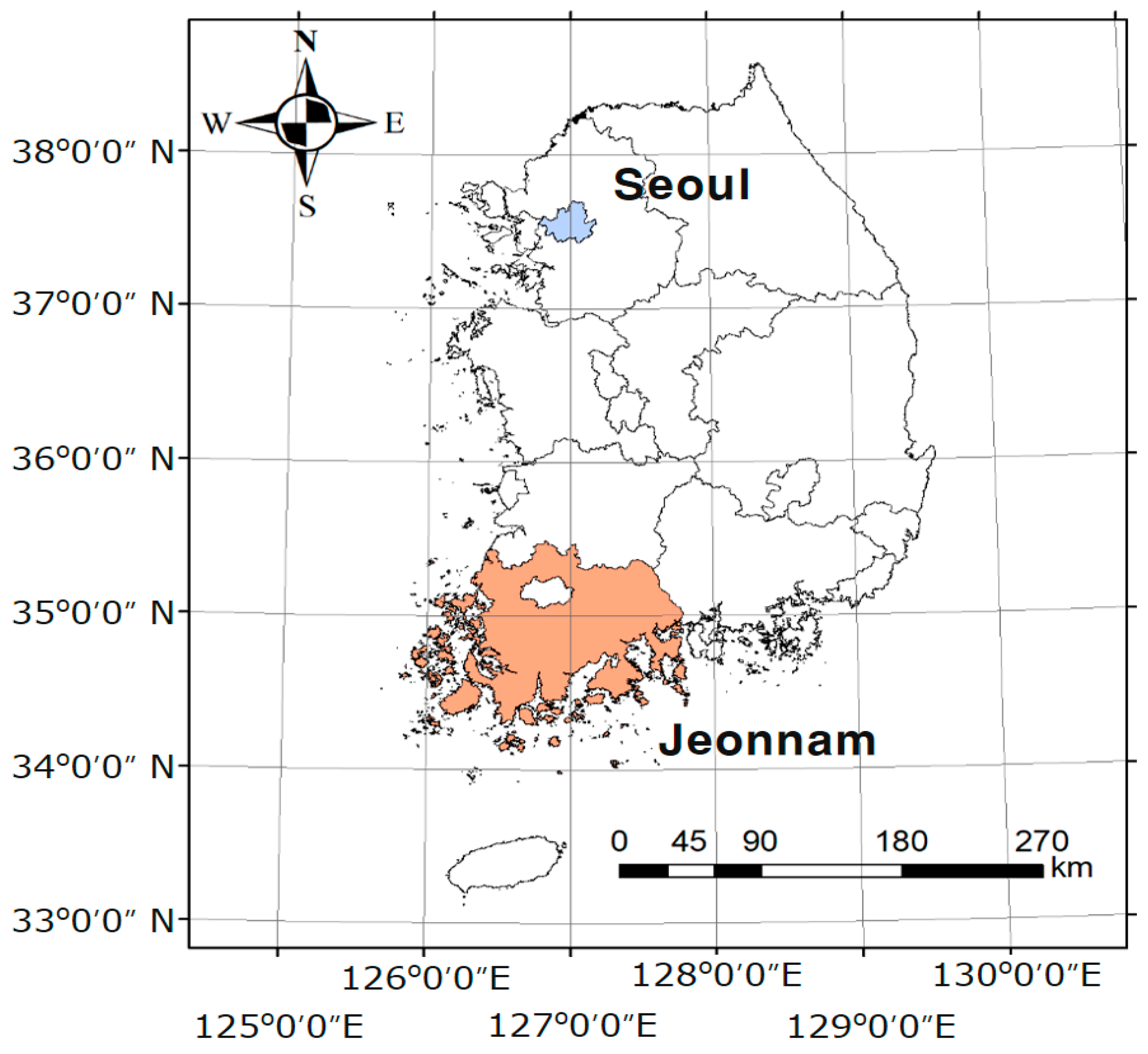

4.1. Experimental Dataset

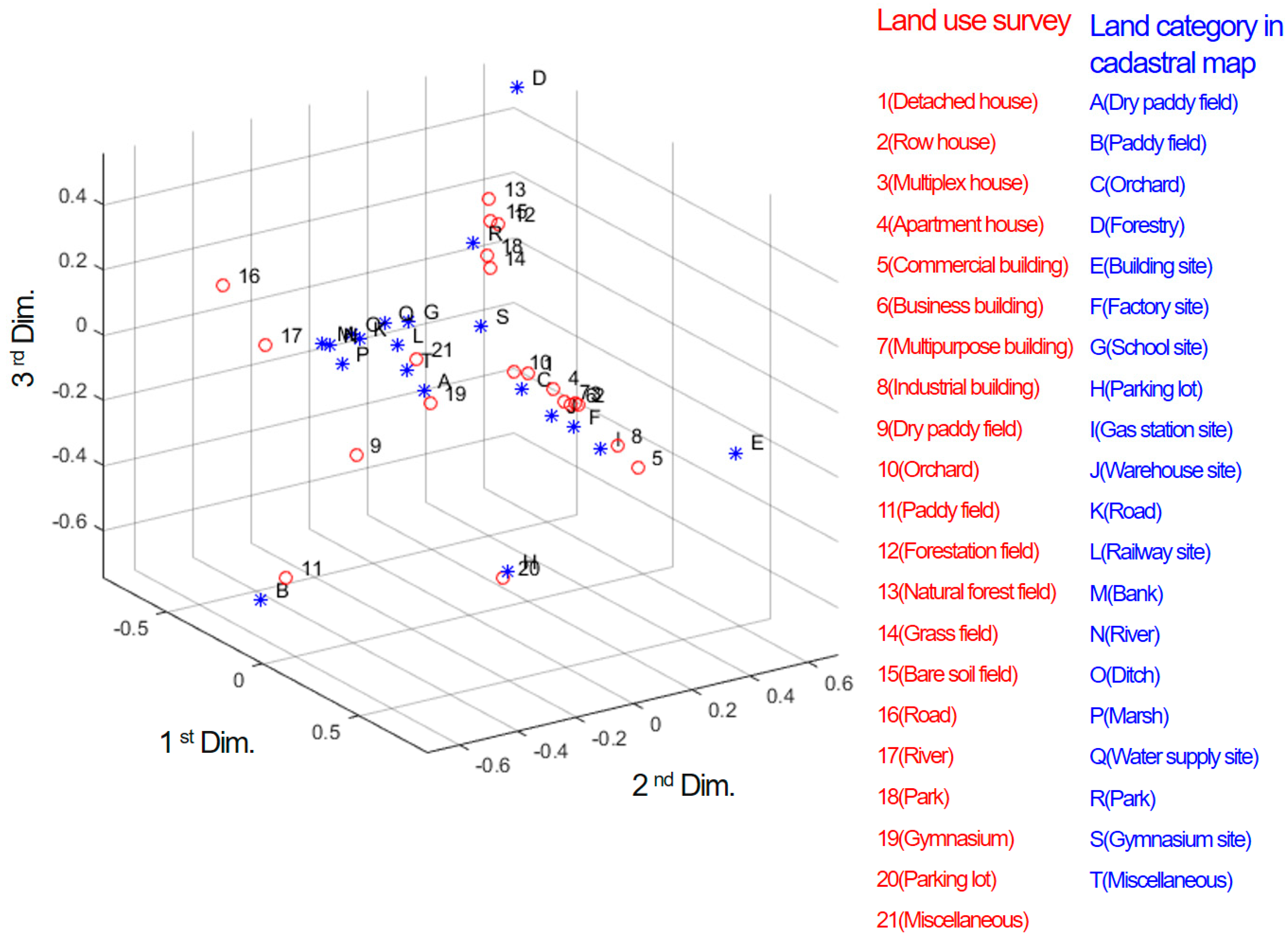

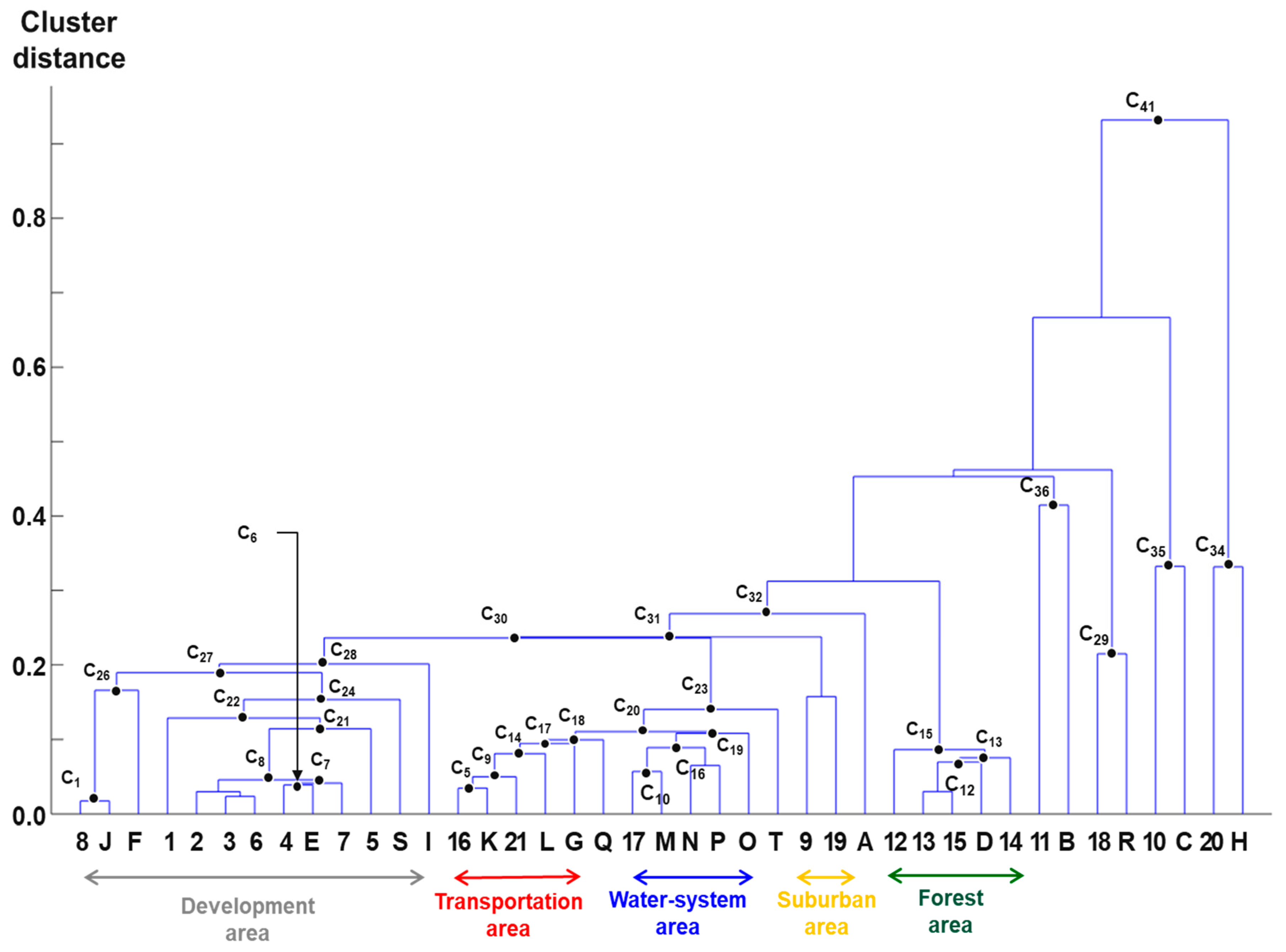

4.2. Results and Discussion

- C1 (8:J): Although a small portion of “8 (industrial building)” are located in “J (Warehouse site)”, these two feature classes have the closest embedded coordinates, as shown in Figure 4. This is because the proposed method performs data normalization in the form of relative frequency, as in Equation (11). Thereafter, “F (Factory site)” is clustered sequentially to process the cluster into C26

- C8 ({2,3,4,6,7}:E): Seoul city is a typical megacity and the capital of the Republic of Korea with a population equal to approximately 10 million, therefore, there are so many residential buildings constructed on the land with land-use category registered as “E (Building site)”. It should be noted that, according to its high land price, detached houses are not popular in the city, except suburban areas. Thus, C8 represents this residence characteristic of the city.

- C21 ({2,3,4,5,6,7}:E), C22 ({1,2,3,4,5,6,7}:E): During the clustering process, “5 (commercial building)” and “1 (detached house)” are sequentially merged into C8. As previously explained, “1 (detached house)” is subsequently merged into the cluster after “5 (commercial building)”.

- C27 ({1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8}:{E,F,J,I,S): C27 is a combination of C24 and C26, which together constitute the main urban development area. Then, “I (Gas station)” is merged into this cluster, which seems to be an isolated land-use category in the urban development area. This is because the safety regulation and high land prices of Seoul city lead to the fact that gas stations are located at a significant distance from central residential and/or commercial sites.

- C10 (17:M), C16 (17:{M, N, O, P}): “17 (river)” and “M (Bank)” are firstly clustered and then, “N (River)”, “P (Marsh)”, and “O (Ditch)” are clustered to form the water-system area. In Seoul city, central and local governments have constructed the banks along most of rivers and streams to prevent flood damage, which explains why “17 (river)” and “M (Bank)” are firstly clustered together, rather than remaining as three considered land-use categories.

- C5 (16:K): This cluster shows that in the two datasets of the land-use record and category, feature classes named “Road” represent nearly the same real-world entity, which means that they have similar geographic concepts for roads.

- C14 ({16, 21}:{K, L}): “21 (miscellaneous)” and “L (Railway site)” are then merged into C5.

- C20 ({16, 17, 21}:{G, K, L, Q, M, N, P, O}): C20 is a combination of C18 and C19 which represents a so-called trans-hydro network. In an urban area such as Seoul city, many small streams have been covered to construct more roads as a part of the continuous urbanization process. In this process, the original land-use category of many land parcels have not been properly changed according to the substantive land-use condition. The inclusion of “G (School site)” seems to be erroneous. In Table 1, there is no proper land-use record class for educational facilities, and this means that the UIS does not manage these facilities. This is due to the fact that according to the Korean administrative legal system, the management of elementary school, middle school, and high school should be governed by local education offices, and not by the local government; therefore, the relevant data is not sufficiently reflected in the UIS, which is managed by local governments.

- C15 ({12,13,14,15}:D): This cluster represents the forest area.

- C36 (11:B), C29 (18:R), C35 (10:C), C34 (20:H): These clusters represent paddy fields, parks, orchards, and parking lot areas, respectively.

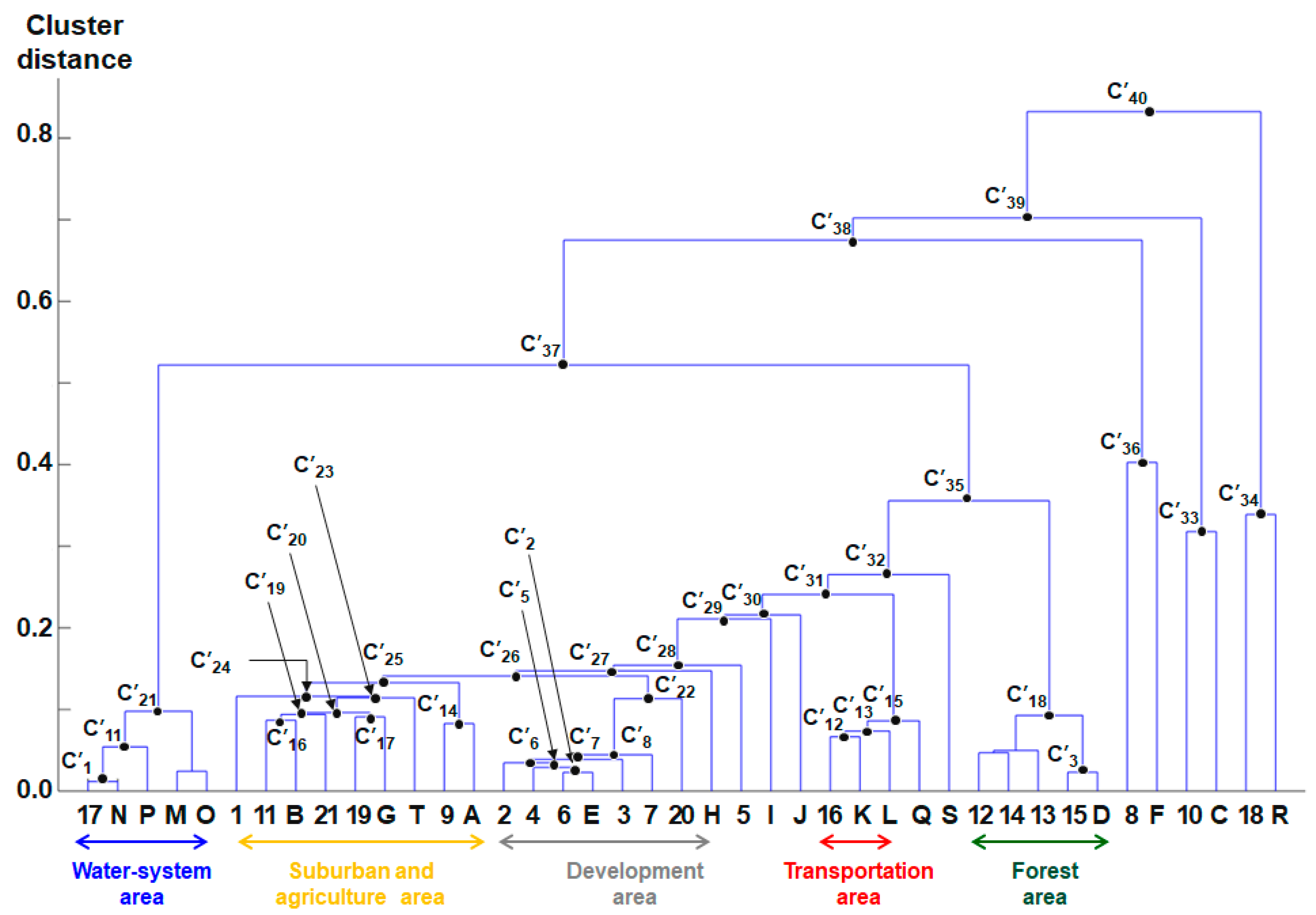

- C’1 (17:N): In the clustering process, the first pair of feature classes identified is “17 (river)” and “N (River)”. In the previous clustering analysis performed for Seoul city, it had a low weight (125/577 = 0.22) according to Equation (11), however, it has a high weight (6083/8225 = 0.74) for the Joennam Province. This is because, in urban areas such as Seoul city, many roads are constructed along rivers or banks; however, in rural areas such as the Jeonnam Province, river-side areas are reserved undeveloped; consequently, the above feature classes are clustered firstly.

- C’21 (17:{M, N, O, P}): Although the order of clustering is different, the result of the analysis is similar to that of Seoul city. It can be confirmed that the 1:N feature class correspondence is the same for the city and the province; however, there is a difference in the correspondence priority of the sub-feature class depending on the regional characteristics.

- C’16 (11:B), C’14 (9:A): Unlike for Seoul city, the cluster order of the feature class related to the agricultural land was higher than that of Seoul city owing to the characteristics of the Jeonnam Province, which has a very high proportion of agricultural land. In other words, it can be confirmed that the actual land-use is performed in the same form as the land plan related to agriculture.

- C’17 (19:G): It shows that various physical education facilities other than educational buildings are installed and operated on the school site. It can be confirmed that physical education facilities are being promoted in connection with the development of school grounds being driven by the welfare projects organized by the local community.

- C’25 ({1, 9, 11, 19, 21}:{A, B, G, T}): This cluster represents the suburban and agriculture area, where “G (School site)” and “T (Miscellaneous)” are included. This is explained by the data management problem similar to that of Seoul city, or by the fact that many sports or agricultural facilities are constructed in the closed school sites in old villages.

- C’13 (16:{K, L}), C’15 (16:{K, L, Q}): Similar to the aforementioned analysis result for Seoul city, “16 (road)” and “K (Road)” were firstly clustered; however, unlike the result for Seoul city, “21 (miscellaneous)” was clustered in the suburban and agriculture area, not the transportation area.

- C’18 ({12,13,14,15}:D): This cluster represents the forest area, similarly to that in the aforementioned case for Seoul city.

- C’36 (8:F), C’33 (10:C), C’34 (18:R): These clusters represent industrial/factory, orchard, park areas, respectively.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaccari, L.; Shvaiko, P.; Marchese, M. A geo-service semantic integration in spatial data infrastructures. Int. J. Spat. Data Infra. 2009, 4, 24–51. [Google Scholar]

- Uitermark, H.T.; van Oosterom, J.M.; Mars, N.J.I.; Molenaar, M. Ontology-based integration of topographic data sets. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2005, 7, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, R.; Alesheikh, A.A.; Hamrah, M. A mixed approach for automated spatial ontology alignment. J. Spat. Sci. 2010, 55, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Casado, M.; Alfonseca, E.; Castells, P. From Wikipedia to Semantic Relationships: A Semi-automated Annotation Approach. In Proceedings of the Third Annual European Semantic Web Conference ESWC’06, Budva, Montenegro, 12 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.J.; Ariza, F.J.; Ureña, M.A.; Blázquez, E.B. Digital map conflation: A review of the process and a proposal for classification. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2011, 25, 1439–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokla, M. Guidelines on geographic ontology integration. In Proceedings of the ISPRS Technical Commission II Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 12–14 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M.A.; Egenhofer, M.J.; Rugg, R.D. Assessing Semantic Similarities among Geospatial Feature Class Definitions. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 1580; Včkovski, A., Brassel, K.E., Schek, H.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1999; pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Duckham, M.; Mason, K.; Stell, J.; Worboys, M. A formal approach to imperfection in geographic information. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2001, 25, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckham, M.; Worboys, M. An algebraic approach to automated geospatial information fusion. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2005, 19, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.F.; Sunna, W. Structural Alignment Methods with Applications to Geospatial Ontologies. Trans. GIS 2008, 12, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccella, A.; Cechich, A.; Gendarmi, D.; Lanubile, F.; Semeraro, G.; Colagrossi, A. Building a global normalized ontology for integrating geographic data sources. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Measuring semantic similarity between land-cover classes for spatial analysis: An ontology hierarchy exploration analysis. Innov. Sys. Softw. Eng. 2016, 12, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.L.; Hong, J.H. Interoperable cross-domain semantic and geospatial framework for automatic change detection. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 86, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, X.; Li, L.; Luo, H.; Hang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Geospatial Information Categories Mapping in a Cross-lingual Environment: A Case Study of “Surface Water” Categories in Chinese and American Topographic Maps. ISPRS Int. J. Geo. Inf. 2016, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, P.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C.; He, H.; Hu, X.; Guan, Z. A multi-feature based automatic approach to geospatial record linking. Int. J. Semt. Web Inf. Sys. 2018, 14, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Conceptual categorizing geographic features from text based on latent semantic analysis and ontologies. Ann. GIS 2016, 22, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sedoc, J.; Gallier, J.; Ungar, L.; Foster, D. Semantic word clusters using signed normalized graph cuts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1601.05403. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Zhu, Y.; Song, J. Progress and Challenges on Entity Alignment of Geographic Knowledge Bases. ISPRS Int. J. Geo. Inf. 2019, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, B. Latent semantic analysis and Fiedler embedding. Linear. Algebra Appl. 2007, 421, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huh, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Yu, K.; Shi, W. Identification of multi-scale corresponding object-set pairs between two polygon datasets with hierarchical co-clustering. ISPRS J. Photo. Rem. Sens. 2014, 88, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, M.; Niyoki, P. Laplacian eigenmaps for dimensionality reduction and data representation. Neural Comp. 2003, 15, 1373–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameh, A.; Wisniewski, J. A trace minimization algorithm for the generalized eigenvalue problem. SIAM J. Num. Anal. 1982, 19, 1243–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Zhilin, L.; Xiaoyong, C. Extended Hausdorff distance for spatial objects in GIS. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2007, 21, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Goodchild, M. An optimisation model for linear feature matching in geographical data conflation. Int. J. Image Data Fus. 2011, 2, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, I. Co-clustering documents and words using bipartite spectral graph partitioning. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, K. Feature correspondence and deformable object matching via agglomerative correspondence clustering. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 27 September–4 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Euzenat, J.; Shavaili, P. Ontology Matching, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brink, L.; Janssen, P.; Quak, W.; Stoter, J. Towards a high level of semantic harmonisation in the geospatial domain. Comp. Environ. Urban Sys. 2017, 62, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Qiu, P.; Liu, X.; Lu, F.; Wan, B. A holistic approach to aligning geospatial data with multidimensional similarity measuring. Int. J. Dig. Earth 2018, 11, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1101 | 213 | 3 | 1329 | 364,662 | 6 | 25 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 955 | 272 | 24 | 85 | 126 | 0 | 16 | 11 | 57 | 307 |

| 2 | 85 | 18 | 0 | 57 | 11,364 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 45 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| 3 | 101 | 28 | 0 | 112 | 69,118 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 130 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 36 |

| 4 | 215 | 45 | 0 | 382 | 20,065 | 9 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 629 | 29 | 2 | 28 | 30 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 51 |

| 5 | 309 | 139 | 0 | 180 | 97,089 | 106 | 5 | 35 | 843 | 2 | 313 | 148 | 7 | 32 | 38 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 281 |

| 6 | 71 | 47 | 0 | 25 | 11,852 | 29 | 8 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 120 | 12 | 1 | 8 | 26 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 144 |

| 7 | 145 | 66 | 1 | 57 | 79,864 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 278 | 31 | 2 | 18 | 25 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 86 |

| 8 | 158 | 118 | 1 | 17 | 3870 | 919 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 52 | 17 | 4 | 14 | 44 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 89 |

| 9 | 8392 | 5690 | 3 | 414 | 669 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 138 | 15 | 34 | 186 | 123 | 9 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 1167 |

| 10 | 224 | 22 | 80 | 128 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 11 | 62 | 3333 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 19 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| 12 | 17 | 4 | 0 | 161 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 428 | 43 | 0 | 10,258 | 645 | 2 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 61 | 0 | 28 | 172 | 14 | 156 |

| 14 | 289 | 38 | 0 | 1254 | 395 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 208 |

| 15 | 26 | 6 | 0 | 415 | 35 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 17 | 22 |

| 16 | 2732 | 1865 | 1 | 2624 | 30,767 | 110 | 197 | 13 | 5 | 2 | 69,102 | 1460 | 346 | 1345 | 2977 | 80 | 301 | 291 | 45 | 1764 |

| 17 | 219 | 261 | 0 | 104 | 65 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 19 | 348 | 1416 | 756 | 59 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 97 |

| 18 | 119 | 79 | 0 | 247 | 1834 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 161 | 30 | 10 | 75 | 38 | 1 | 31 | 2200 | 8 | 109 |

| 19 | 120 | 89 | 0 | 29 | 114 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 12 | 2 | 14 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 14 |

| 20 | 46 | 104 | 0 | 36 | 381 | 1 | 0 | 387 | 2 | 0 | 45 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 52 |

| 21 | 61 | 10 | 0 | 36 | 144 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 16 | 3 | 157 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 166 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29,886 | 13,270 | 187 | 4603 | 537,129 | 25 | 218 | 9 | 6 | 92 | 350 | 112 | 6 | 73 | 55 | 110 | 6 | 1 | 238 | 3684 |

| 2 | 109 | 92 | 3 | 15 | 778 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 3 | 75 | 34 | 0 | 6 | 700 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | 192 | 131 | 1 | 67 | 1289 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 5 | 1257 | 1567 | 15 | 269 | 33,248 | 88 | 14 | 38 | 936 | 85 | 114 | 27 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 2273 |

| 6 | 297 | 237 | 3 | 71 | 2978 | 4 | 46 | 12 | 4 | 30 | 2 | 24 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 242 |

| 7 | 1000 | 1148 | 11 | 148 | 27,633 | 15 | 9 | 11 | 51 | 32 | 24 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 976 |

| 8 | 875 | 688 | 7 | 257 | 1972 | 4634 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 125 | 40 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 22 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 1970 |

| 9 | 962,643 | 50,201 | 934 | 46,482 | 12,995 | 36 | 135 | 4 | 7 | 63 | 1038 | 401 | 17 | 448 | 115 | 623 | 57 | 13 | 116 | 4726 |

| 10 | 11,374 | 4357 | 7009 | 2382 | 337 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 161 |

| 11 | 27,823 | 1,170,616 | 338 | 4468 | 2736 | 23 | 43 | 3 | 0 | 48 | 1053 | 73 | 51 | 656 | 302 | 1613 | 50 | 4 | 34 | 7872 |

| 12 | 320 | 266 | 0 | 27,706 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 96 | 0 | |

| 13 | 2442 | 1034 | 30 | 505,169 | 430 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 346 | 75 | 5 | 27 | 103 | 143 | 47 | 7 | 19 | 159 |

| 14 | 7919 | 4437 | 30 | 79,618 | 722 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 26 | 2 | 14 | 7 | 47 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 378 |

| 15 | 169 | 83 | 5 | 5155 | 64 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 11 | 37 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 77 | 9 | 98 | 255 |

| 16 | 14,357 | 20,976 | 47 | 8066 | 10,027 | 68 | 179 | 8 | 3 | 24 | 90,897 | 1605 | 121 | 916 | 774 | 459 | 751 | 8 | 39 | 1301 |

| 17 | 3182 | 8267 | 8 | 1752 | 450 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 343 | 20 | 1474 | 6083 | 9342 | 9110 | 97 | 1 | 2 | 792 |

| 18 | 169 | 140 | 0 | 109 | 194 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 240 | 3 | 69 |

| 19 | 114 | 201 | 0 | 83 | 311 | 0 | 212 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 29 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 124 | 151 | 1 | 45 | 231 | 1 | 9 | 214 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 152 |

| 21 | 885 | 889 | 5 | 313 | 713 | 2 | 123 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 5 | 5 | 221 | 18 | 0 | 20 | 1343 |

| No | Feature Class-Set Pair | F-Measure | No | Feature Class-Set Pair | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | {8}:{J} | 0.003 | C20 | {16,17,21}:{G,K,L M,N,O,P} | 0.772 |

| C2 | {3,6}:Null | C21 | {2,3,4,5,6,7}:{E} | 0.586 | |

| C3 | {2,3,6}: Null | C22 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7}:{E} | 0.964 | |

| C4 | {13,15}: Null | C23 | {16,17,21}:{G,K,L M,N,O,P,Q,T} | 0.773 | |

| C5 | {16}:{K} | 0.734 | C24 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7}:{E,S} | 0.964 |

| C6 | {4}:{E} | 0.056 | C25 | {9,19}: Null | |

| C7 | {4,7}:{E} | 0.251 | C26 | {8}:{F,J} | 0.283 |

| C8 | {2,3,4,6,7}:{E} | 0.433 | C27 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8}:{E,F,J,S} | 0.966 |

| C9 | {16,21}:{K} | 0.732 | C28 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8}:{E,F,I,J,S} | 0.967 |

| C10 | {17}:{M} | 0.163 | C29 | {18}:{R} | 0.569 |

| C11 | {Nan}:{35,37} | C30 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,16,17,21}:{E,F,G,I,J,K,L,M,N,O,P,Q,S,T} | 0.987 | |

| C12 | {13,15}:{D} | 0.703 | C31 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, 16,17,19,21}:{E,F,G,I,J,K,L,M,N,O,P,Q,S,T} | 0.979 |

| C13 | {13,14,15}:{D} | 0.730 | C32 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,16,17,19,21}:{A,E,F,G,I,J,K,L,M,N,O,P,Q,S,T} | 0.987 |

| C14 | {16,21}:{K,L} | 0.739 | C33 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,21}:{A,D,E,F,G,I,J,K,L,M,N,O,P,Q,S,T} | 0.992 |

| C15 | {12,13,14,15}:{D} | 0.735 | C34 | {20}:{H} | 0.493 |

| C16 | {17}:{M,N,P} | 0.464 | C35 | {10}:{C} | 0.288 |

| C17 | {16,21}:{G,K,L} | 0.740 | C36 | {11}:{B} | 0.424 |

| C18 | {16,21}:{G,K,L,Q} | 0.741 | ⋮ | ||

| C19 | {17}:{M,N,O,P} | 0.422 | C40 | All:All | 1.000 |

| No | Feature Class-Set Pair | F-Measure | No | Feature Class-Set Pair | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C’1 | {17}:{N} | 0.247 | C’18 | {12,13,14,15}:{D} | 0.933 |

| C’2 | {6}:{E} | 0.009 | C’19 | {11,21}:{B} | 0.937 |

| C’3 | {15}: {D} | 0.015 | C’20 | {11,19,21}:{B,G} | 0.936 |

| C’4 | Null:{M,O} | C’21 | {17}:{M,N,O,P} | 0.702 | |

| C’5 | {4,6}:{E} | 0.013 | C’22 | {2,3,4,6,7,20}:{E} | 0.100 |

| C’6 | {2,4,6}:{E} | 0.016 | C’23 | {11,19,21}:{B,G,T} | 0.934 |

| C’7 | {2,3,4,6}:{E} | 0.018 | C’24 | {1,11,19,21}:{B,G,T} | 0.768 |

| C’8 | {2,3,4,6,7}:{E} | 0.099 | C’25 | {1,9,11,19,21}:{A,B,G,T} | 0.864 |

| C’9 | {12,14}:Null | C’26 | {1,2,3,4,7,6,9,11,19,20,21}:{A,B,E,G,T} | 0.965 | |

| C’10 | {12,13,14}:Null | ⋮ | |||

| C’11 | {17}:{N,P} | 0.493 | C’33 | {10}:{C} | 0.408 |

| C’12 | {16}:{K} | 0.742 | C’34 | {18}:{R} | 0.384 |

| C’13 | {16}:{K,L} | 0.747 | C’35 | {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,19,20,21}:{A,B,D,E,G,H,I,J,K,L,Q,ST} | 0.993 |

| C’14 | {9}:{A} | 0.897 | C’36 | {8}:{F} | 0.596 |

| C’15 | {16}:{K,L,O} | 0.750 | ⋮ | ||

| C’16 | {11}:{B} | 0.938 | C’40 | All:All | 1.000 |

| C’17 | {19}:{G} | 0.207 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huh, Y. Hierarchical Semantic Correspondence Analysis on Feature Classes between Two Geospatial Datasets Using a Graph Embedding Method. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8110479

Huh Y. Hierarchical Semantic Correspondence Analysis on Feature Classes between Two Geospatial Datasets Using a Graph Embedding Method. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2019; 8(11):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8110479

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuh, Yong. 2019. "Hierarchical Semantic Correspondence Analysis on Feature Classes between Two Geospatial Datasets Using a Graph Embedding Method" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 8, no. 11: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8110479

APA StyleHuh, Y. (2019). Hierarchical Semantic Correspondence Analysis on Feature Classes between Two Geospatial Datasets Using a Graph Embedding Method. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8(11), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8110479