Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information

Abstract

:1. Introduction

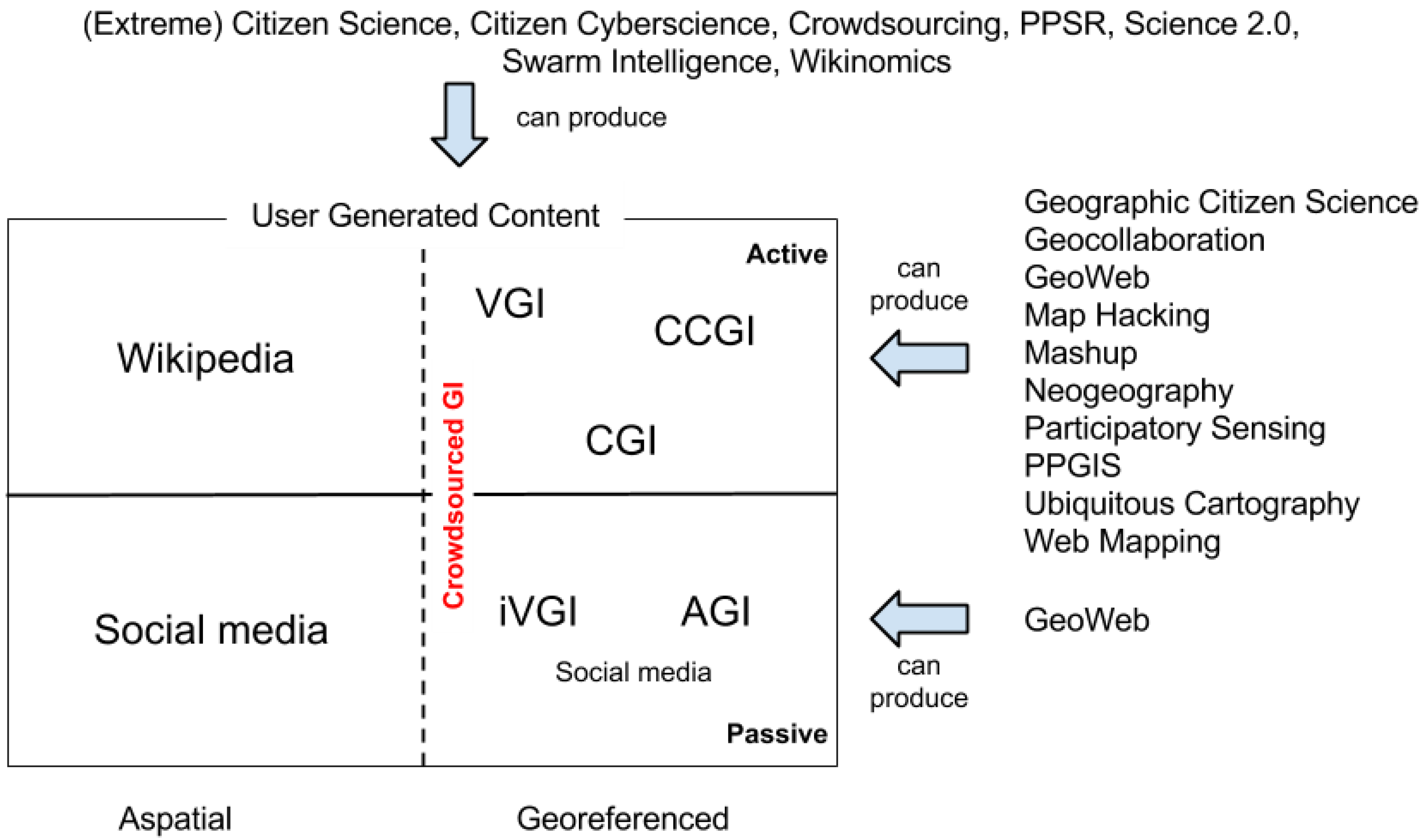

2. A Review of the Terminology

2.1. Definitions

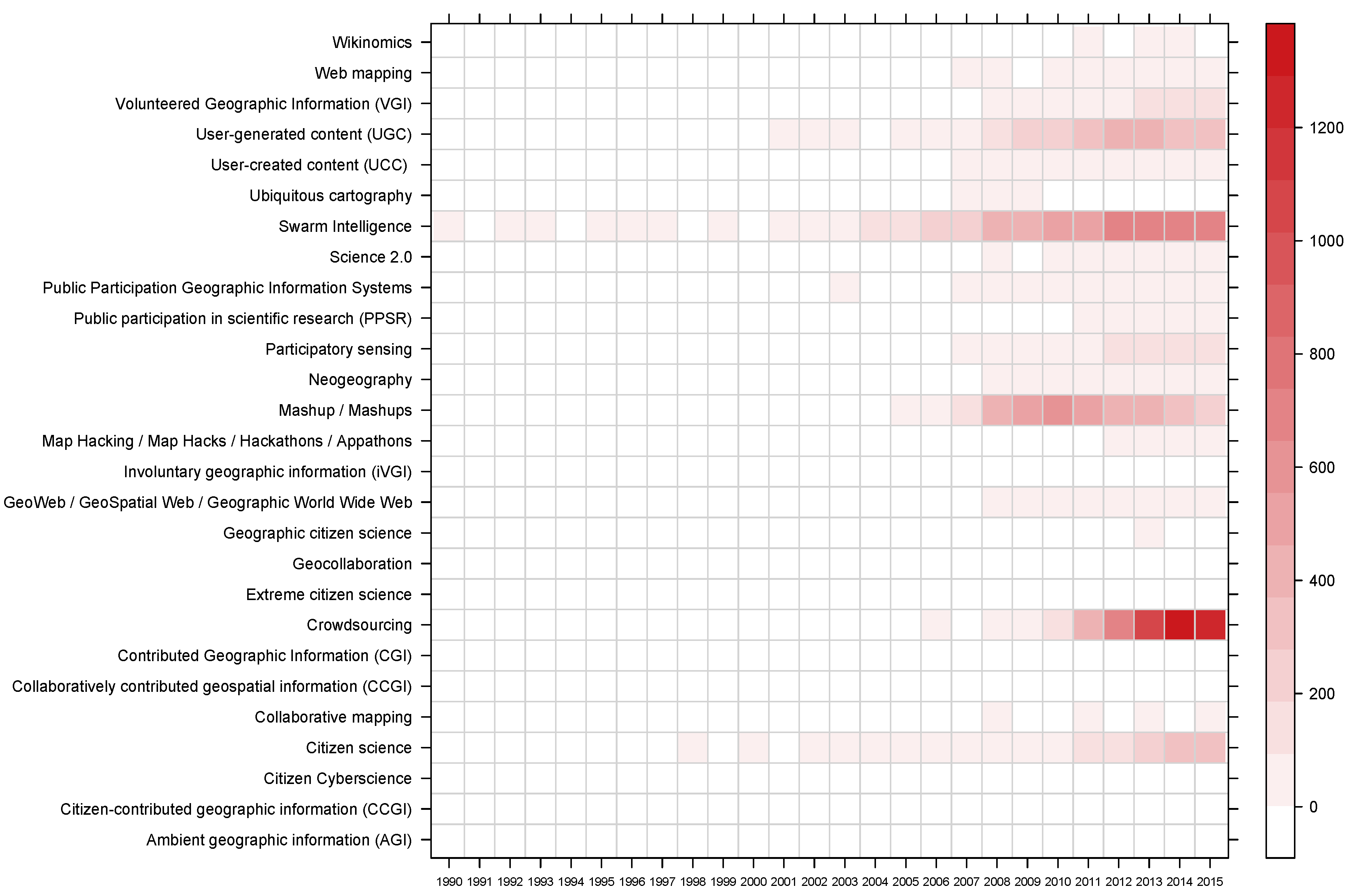

2.2. Temporal Analysis of the Literature

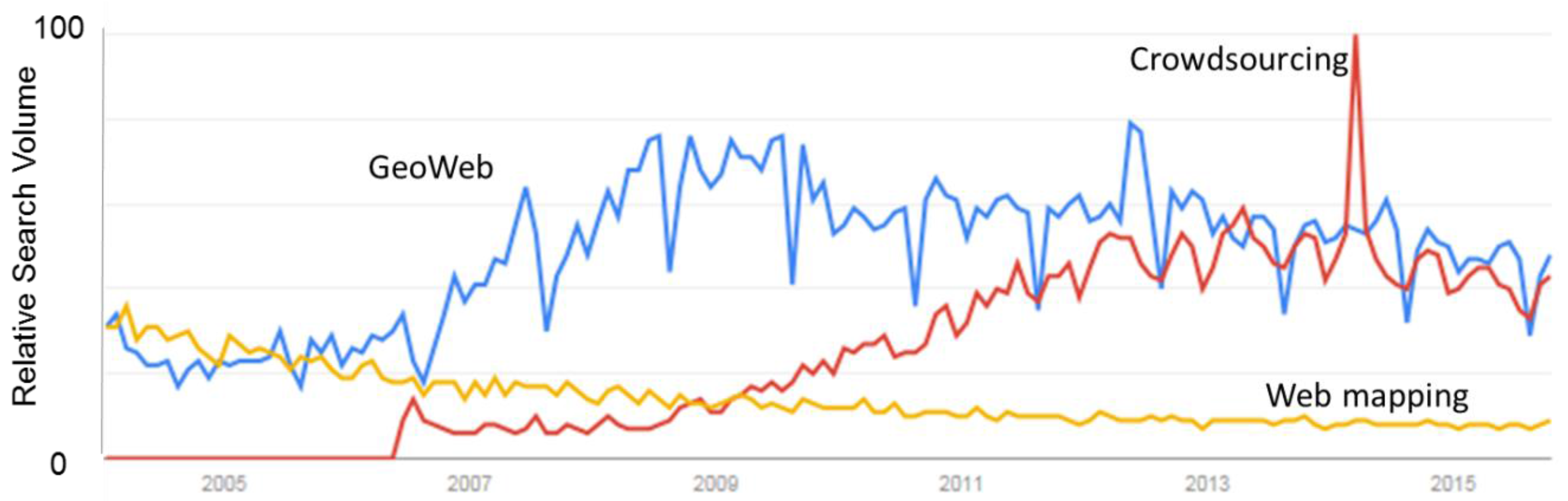

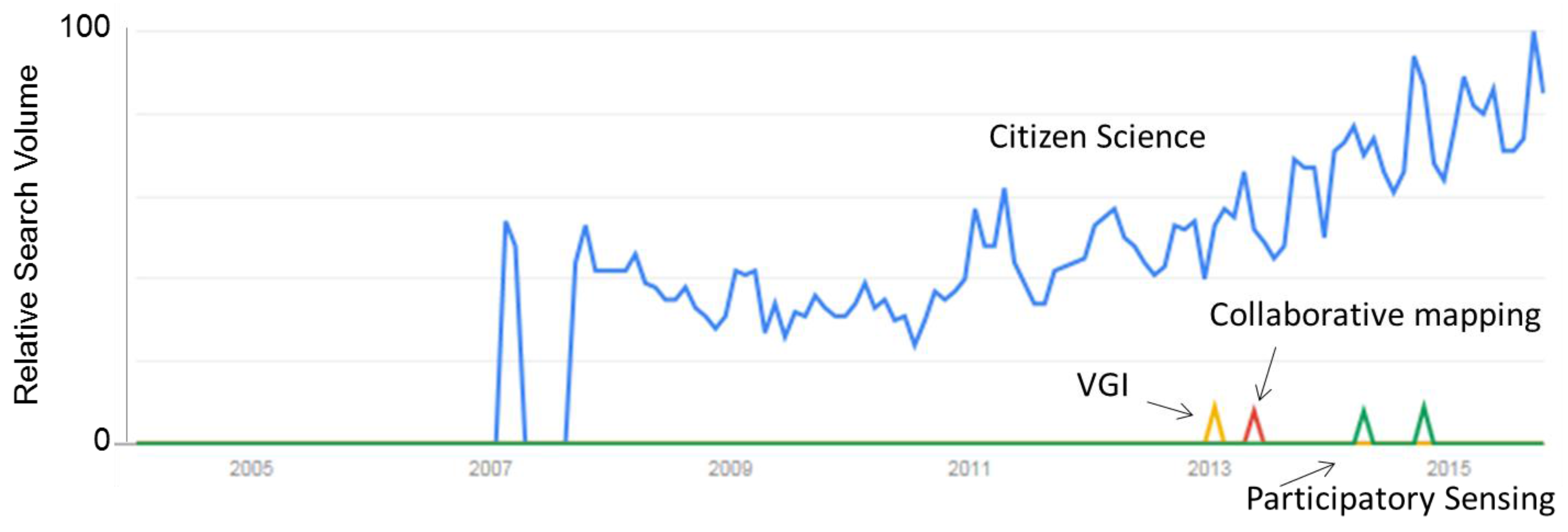

2.3. Google Trends Analysis

3. The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information

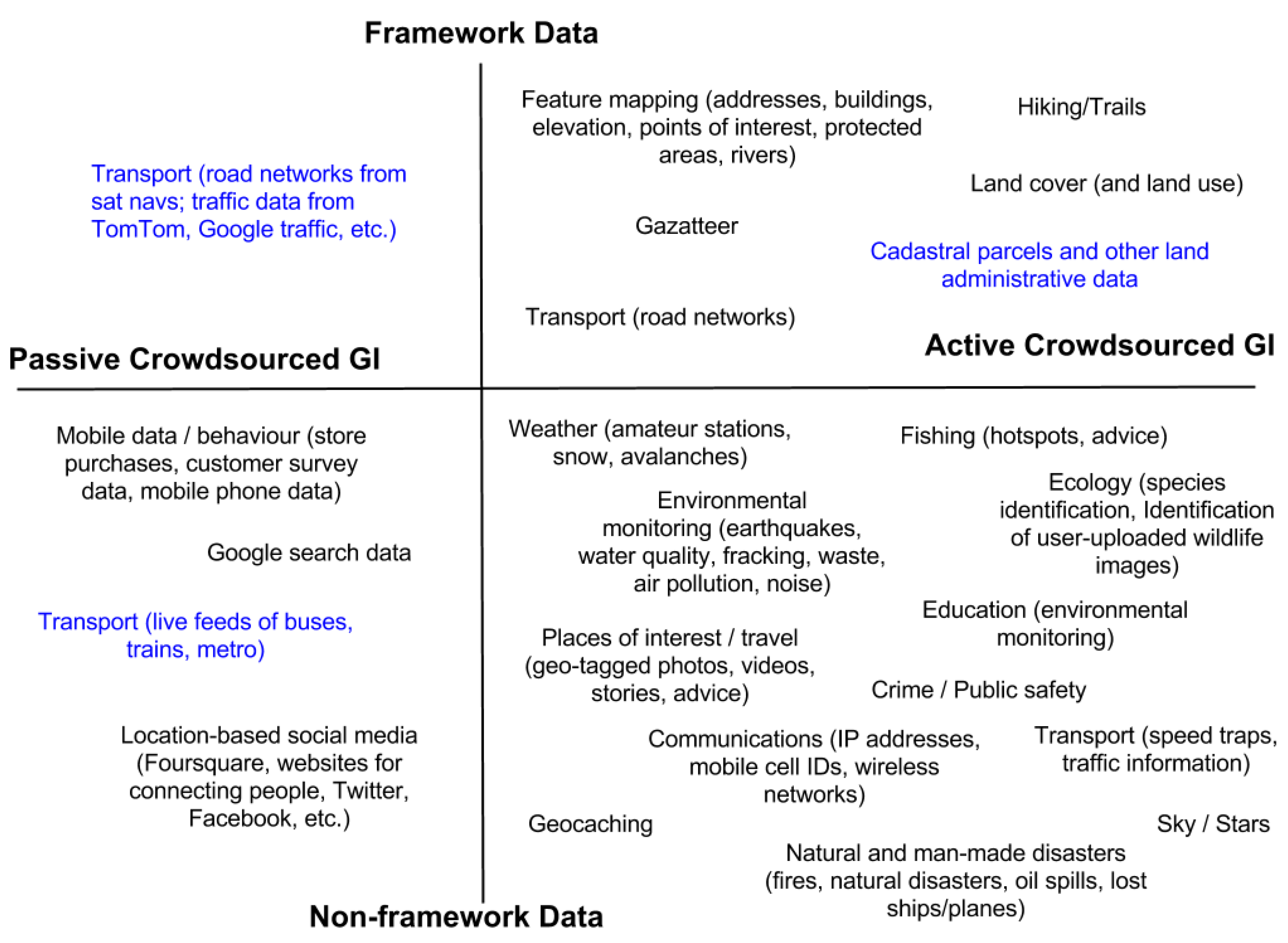

3.1. Theme

3.2. Nature and Types of Crowdsourced Geographic Information

3.3. Expertise and Training

3.4. Crowdsourced Geographic Information Availability and Metadata

3.5. Quality and Use of the Data for Research

3.6. Information about Participants

3.7. Incentives for Participation

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- There is a need to gain a better understanding of the currency of the data. This issue is critical for integration of crowdsourced geographic information with authoritative sources, particularly if crowdsourced geographic information is to be used for change detection. Crowdsourced geographic information is often assumed to be more current than the framework equivalent, but it is not always clear whether this is the case and requires further study.

- Investigation of how the interrelationships between terms in Table 1 have changed and evolved over time could be undertaken since phrases come in and out of fashion or they become synonyms for related but different activities. This would require an extension of this research into the domain of semiotics, for example, to develop a semantic or text mining analysis of the similarity of the changing contexts within which terms are used and is the subject of a research topic on its own.

- More research into incentives for participation and citizen motivations is required. More use of online surveys, see for example, [84,85], may help to better meet the needs of citizens in the future. For example, how can citizens be encouraged to map an area that has already been mapped in the last few years or be more actively engaged in change detection mapping?

- Issues of copyright, ownership, data privacy and licensing will become much more prevalent in the future as data contributed by citizens is integrated with base layers that are created by third parties. Saunders et al. [86] consider the licensing and copyright issues from a Canadian legal perspective when using a range of online current mapping tools. Data privacy laws vary from country to country but generally require the protection of personal information, i.e., information that could allow people to be identified [87]. However, location-based information can reveal personal information that could be disclosed without consent if the users of the data are not careful in how the data are subsequently employed [88]. Ethical issues surrounding the use of crowdsourced geographic information with respect to health and disease surveillance have been raised by Blatt [89] so this is a growing area where further research is needed.

- Data interoperability was not considered in the above review of websites but if the data are to be used in future projects or for different purposes than those for which the data were originally collected, more research into data standards for crowdsourced geographic information is required. Work is ongoing in this area within the COBWEB citizen observatory project [90] while the authors of [91] have presented a unified model for semantic interoperability of sensor data and VGI.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGI | Ambient Geographic Information |

| CCGI | Citizen-contributed Geographic Information OR Collaboratively Contributed Geographic Information |

| CGI | Contributed Geographic Information |

| PPGIS | Public Participaton in Geographic Information Systems |

| PPSR | Public Participation in Scientific Research |

| iVGI | Involuntary Volunteered Geographic Information |

| UCC | User Created Content |

| UGC | User Generated Content |

| VGI | Volunteered Geographic Information |

References

- McConchie, A. Hacker cartography: Crowdsourced geography, OpenStreetMap, and the hacker political imaginary. ACME Int. E-J. Crit. Geogr. 2015, 14, 874–898. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Introduction to Neogeography; O’Reilly: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, J. The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Mag. 2006, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen science: A developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. BioScience 2009, 59, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumm, J.; Davies, N.; Narayanaswami, C. User-Generated Content. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2008, 7, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar Arsanjani, J.; Zipf, A.; Mooney, P.; Helbich, M. OpenStreetMap in GIScience; Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, A.; Croitoru, A.; Stefanidis, A.; Radzikowski, J. #Earthquake: Twitter as a distributed sensor system. Trans. GIS 2013, 17, 124–147. [Google Scholar]

- Estima, J.; Painho, M. Flickr geotagged and publicly available photos: Preliminary study of its adequacy for helping quality control of Corine land cover. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2013; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Carlini, M., Torre, C.M., Nguyen, H.-Q., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, F. To volunteer or to contribute locational information? Towards truth in labeling for crowdsourced geographic information. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge; Sui, D., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Thill, J.-C. Volunteered Geographic Information: Towards the establishment of a new paradigm. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 53, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heipke, C. Crowdsourcing geospatial data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2010, 65, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyratos, S.; Lutz, M.; Pantisano, F. Characteristics of citizen-contributed geographic information. In Proceedings of the AGILE’2014 International Conference on Geographic Information Science, Castellón, Spain, 3–6 June 2014.

- Elwood, S.; Goodchild, M.; Sui, D.Z. Vgi-Net. Available online: http://vgi.spatial.ucsb.edu/ (accessed on 6 December 2013).

- Elwood, S.; Goodchild, M.F.; Sui, D.Z. Researching volunteered geographic information: Spatial data, geographic research, and new social practice. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2012, 102, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, A.; Crooks, A.; Radzikowski, J. Harvesting ambient geospatial information from social media feeds. GeoJournal 2013, 78, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science Communication Unit. Science for Environment Policy Indepth Report: Environmental Citizen Science; University of the West of England: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonney, R. Citizen science: A lab tradition. Living Bird 1996, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Rushing, A.; Primack, R.; Bonney, R. The history of public participation in ecological research. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOCIENTIZE. White Paper on Citizen Science for Europe; Socentize Consortium: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haklay, M. Neogeography and the delusion of democratisation. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGillavry, E. Collaborative Mapping; Webmapper: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bishr, M.; Kuhn, W. Geospatial information bottom-up: A matter of trust and semantics. In The European Information Society; Fabrikant, S.I., Wachowicz, M., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 365–387. [Google Scholar]

- Keßler, C.; Maué, P.; Heuer, J.T.; Bartoschek, T. Bottom-up gazetteers: Learning from the implicit semantics of geotags. In GeoSpatial Semantics; Janowicz, K., Raubal, M., Levashkin, S., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s mechanical turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estellés-Arolas, E.; González-Ladrón-de-Guevara, F. Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition. J. Inf. Sci. 2012, 38, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M. Citizen science and volunteered geographic information: Overview and typology of participation. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge; Sui, D., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Maceachren, A.M.; Brewer, I. Developing a conceptual framework for visually-enabled geocollaboration. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2004, 18, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, B. Geocollaboration. In Encyclopedia of Geography; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1209–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, C. An Architecture of Cyberspace: Spatialization of the Internet; U.S. Army Construction Engineering Research Laboratory: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994.

- MacGuire, D. GeoWeb 2.0: Implications for ESDI. In Proceedings of the 12th EC-GI&GIS Workshop, Innsbruck, Austria, 21–23 June 2006.

- Fischer, F. VGI as big data: A new but delicate geographic data source. GeoInformatics 2012, 3, 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Snook, T. Hacking is a Mindset, not a Skillset: Why Civic Hacking is Key for Contemporary Creativity. Available online: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2014/01/16/hacking-is-a-mindset-not-a-skillset/ (accessed on 16 July 2014).

- Sfetcu, N. Game Preview; Nicolae Sfetcu: Bucharest, Romania, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, D. Mashup and the spirit of GIS and geography. GeoWorld 2009, 12, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Szott, R. Neogeography Defined. Available online: http://placekraft.blogspot.co.uk/2006/04/neogeography-defined.html (accessed on 6 December 2013).

- Szott, R. Psychogeography vs. Neogeography. Available online: http://placekraft.blogspot.co.uk/2006/04/psychogeography-vs-neogeography.html (accessed on 6 December 2013).

- Burke, J.A.; Estrin, D.; Hansen, M.; Parker, A.; Ramanathan, N.; Reddy, S.; Srivastava, M.B. Participatory Sensing; Center for Embedded Network Sensing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karatzas, K.D. Participatory environmental sensing for quality of life information services. In Information Technologies in Environmental Engineering; Golinska, P., Fertsch, M., Marx-Gómez, J., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bonney, R.; Ballard, H.; Jordan, R.; McCallie, E.; Phillips, T.; Shirk, J.; Wilderman, C.C. Public Participation in Scientific Research: Defining the Field and Assessing Its Potential for Informal Science Education; Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education (CAISE): Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sieber, R. Public participation geographic information systems: A literature review and framework. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2006, 96, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. Science 2.0. Science 2008, 319, 1349–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bücheler, T.; Sieg, J.H. Understanding Science 2.0: Crowdsourcing and open innovation in the scientific method. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2011, 7, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, G.; Bennett, D.A.; Morita, T. Towards ubiquitous cartography. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2007, 34, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Participative Web: User-Created Content; OECD: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tsou, M.-H. Revisiting web cartography in the United States: The rise of user-centered design. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2011, 38, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapscott, D.; Williams, A.D. Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything; Portfolio: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Comber, A.; Schade, S.; See, L.; Mooney, P.; Foody, G. Semantic analysis of citizen sensing, crowdsourcing and VGI. In Proceedings of the AGILE’2014 International Conference on Geographic Information Science, Castellón, Spain, 3–6 June 2014.

- Google. Google Trends. Available online: https://www.google.com/trends/ (accessed on 31 October 2015).

- Whittaker, J.; McLennan, B.; Handmer, J. A review of informal volunteerism in emergencies and disasters: Definition, opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 13, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, R. The 1996 geographical association land use-UK survey: A geographical commitment. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 1999, 8, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvertown, J. A new dawn for citizen science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ushahidi. Ushahidi. Available online: http://www.ushahidi.com (accessed on 6 December 2014).

- Tomnod. Tomnod. Available online: http://www.tomnod.com (accessed on 6 December 2014).

- Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. Humanitarian OpenStreetMap. Available online: http://hotsom.org (accessed on 6 December 2014).

- Muller, C.L.; Chapman, L.; Johnston, S.; Kidd, C.; Illingworth, S.; Foody, G.; Overeem, A.; Leigh, R.R. Crowdsourcing for climate and atmospheric sciences: Current status and future potential. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 3185–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, V.; Skopeliti, A. Measures and indicators of VGI quality: An overview. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 1, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, L.; Comber, A.; Salk, C.; Fritz, S.; van der Velde, M.; Perger, C.; Schill, C.; McCallum, I.; Kraxner, F.; Obersteiner, M. Comparing the quality of crowdsourced data contributed by expert and non-experts. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorn, H.; Törnros, T.; Zipf, A. Quality evaluation of VGI using authoritative data—A comparison with land use data in Southern Germany. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 1657–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neis, P.; Zielstra, D. Recent developments and future trends in volunteered geographic information research: The case of OpenStreetMap. Future Internet 2014, 6, 76–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar Arsanjani, J.; Mooney, P.; Zipf, A.; Schauss, A. Quality assessment of the contributed land use information from OpenStreetMap versus authoritative datasets. In OpenStreetMap in GIScience; Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Jokar Arsanjani, J., Zipf, A., Mooney, P., Helbich, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, C.; Neis, P.; Zipf, A. A comprehensive framework for intrinsic OpenStreetMap quality analysis. Trans. GIS 2014, 18, 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Fan, H.; Jing, N.; Sun, Y.; Zipf, A. Temporal analysis on contribution inequality in OpenStreetMap: A comparative study for four countries. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinnamon, J.; Schuurman, N. Confronting the data-divide in a time of spatial turns and volunteered geographic information. GeoJournal 2012, 78, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordogna, G.; Carrara, P.; Criscuolo, L.; Pepe, M.; Rampini, A. On predicting and improving the quality of Volunteer Geographic Information projects. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerle, N.; Hoffman, R.R. Collaborative damage mapping for emergency response: The role of cognitive systems engineering. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Schönberger, V.; Cukier, K. Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Liu, X. Scaling of geographic space from the perspective of city and field blocks and using volunteered geographic information. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 26, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M.; Basiouka, S.; Antoniou, V.; Ather, A. How many volunteers does it take to map an area well? The validity of Linus’ Law to volunteered geographic information. Cartogr. J. 2010, 47, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Li, L. Assuring the quality of volunteered geographic information. Spat. Stat. 2012, 1, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M.; See, L.; Fritz, S.; van der Velde, M.; Perger, C.; Schill, C.; Boyd, D.S.; Comber, A. Accurate attribute mapping from Volunteered Geographic Information: Issues of volunteer quantity and quality. Cartogr. J. 2015, 52, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fonte, C.C.; Bastin, L.; See, L.; Foody, G.; Lupia, F. Usability of VGI for validation of land cover maps. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 1269–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Fan, H.; Jing, N. Amateur or professional: Assessing the expertise of major contributors in OpenStreetMap based on contributing behaviors. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neis, P.; Zielstra, D.; Zipf, A. Comparison of volunteered geographic information data contributions and community development for selected world regions. Future Internet 2013, 5, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, G.D.; Oh, O.; Kishore, R. Rules of crowdsourcing: Models, issues, and systems of control. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2013, 30, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu-Raimond, A.-M.; Hart, G.; Foody, G.M.; Touya, G.; Kellenberger, T.; Demetriou, D. The scale of VGI in map production: A perspective of European National Mapping Agencies. Trans. GIS 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, M.; Rajabifard, A.; Olfat, H.; Williamson, I. Geospatial Metadata 2.0—An approach for Volunteered Geographic Information. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2014, 48, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahbakhsh, M.; Benatallah, B.; Ignjatovic, A.; Motahari-Nezhad, H.R.; Bertino, E.; Dustdar, S. Quality control in crowdsourcing systems: Issues and directions. IEEE Internet Comput. 2013, 17, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaili, R.; Naseri, F.; Esmaili, A. Quality assessment of volunteered geographic information. Am. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2013, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, D. Potential contributions and challenges of VGI for conventional topographic base-mapping programs. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge; Sui, D., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Bishr, M.; Mantelas, L. A trust and reputation model for filtering and classifying knowledge about urban growth. GeoJournal 2008, 72, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, F.; Sosa, R.; Delgado, T. GeoBI and big VGI for crime analysis and report. In Proceedings of the 2015 3rd International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud), Rome, Italy, 24–26 August 2015; pp. 481–488.

- Mooney, P.; Rehrl, K.; Hochmair, H. Action and interaction in volunteered geographic information: A workshop review. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2013, 7, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land-Zandstra, A.M.; Devilee, J.L.A.; Snik, F.; Buurmeijer, F.; van den Broek, J.M. Citizen science on a smartphone: Participants motivations and learning. Public Underst. Sci. 2016, 25, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.; Raddick, M.J.; Lardner, A.; Carney, K. An exploratory factor analysis of motivations for participating in Zooniverse, a collection of virtual citizen science projects. In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; pp. 610–619.

- Saunders, A.; Scassa, T.; Lauriault, T.P. Legal issues in maps built on third party base layers. Geomatica 2012, 66, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scassa, T. Legal issues with volunteered geographic information. Can. Geogr. 2013, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scassa, T. Geographic information as personal information. Oxf. Univ. Commonw. Law J. 2010, 10, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, A.J. Data privacy and ethical uses of Volunteered Geographic Information. In Health, Science, and Place; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cobweb. Cobweb. Available online: http://cobwebproject.eu (accessed on 6 November 2015).

- Bakillah, M.; Liang, S.; Zipf, A.; Arsanjani, J. Semantic interoperability of sensor data with Volunteered Geographic Information: A unified model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2013, 2, 766–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capineri, C. European Handbook of Crowdsourced Geographic Information; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Terminology | Definition | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Ambient geographic information (AGI) (2013) | This term first appeared in Stefanidis et al. [16] in relation to the analysis of Twitter data. AGI, in contrast to VGI, is passively contributed data in which the people themselves may be seen as the observable phenomena, rather than only as sensors. These observations can therefore help us to better understand human behavior and patterns in social systems. However, the focus can also be on the content of the data. | I |

| Citizen-contributed geographic information (CCGI) (2014) | CCGI was introduced in Spyratos et al. [13], where the definition is based on the purpose of the data collection exercise. CCGI therefore has two main components, i.e., information generated for scientific-oriented voluntary activities, i.e., VGI, or from social media, which they refer to as social geographic data (SGD). | I |

| Citizen Cyberscience (2009) | Citizen Cyberscience is the provision and application of inexpensive distributed computing power, e.g., the Large Hadron Collider LHC@ home project developed by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) and SETI@Home. | P |

| Citizen science (Mid-1990s) | Citizen science was the name of a book written by Alan Irwin in 1995 which discussed the complementary nature of knowledge from citizens with that of science [17]. Rick Bonney of Cornell’s Laboratory of Ornithology first referred to citizen science in the mid-nineties [18] as an alternative term for public participation in scientific research although citizens have had a long history of involvement in science [19]. A more recent definition from the Green Paper on Citizen Science for Europe [20] reads as follows: “the general public engagement in scientific research activities when citizens actively contribute to science either with their intellectual effort or surrounding knowledge or with their tools and resources. Participants provide experimental data and facilities for researchers, raise new questions and co-create a new scientific culture. While adding value, volunteers acquire new learning and skills, and deeper understanding of the scientific work in an appealing way. As a result of this open, networked and trans-disciplinary scenario, science-society-policy interactions are improved leading to a more democratic research, based on evidence-informed decision making as is scientific research conducted, in whole or in part, by amateur or non-professional scientists.” The idea of more “democratic research” and the democratization of GIS and geographic knowledge has recently been challenged in Reference [21], who argues that neogeography (see below for a definition) has opened up access to geographic information to only a small part of society (technologically literate, educated, etc.). | P |

| Collaborative mapping (2003) | Collaborative mapping is the collective creation of online maps (as representations of real-world phenomena) that can be accessed, modified and annotated online by multiple contributors as outlined in MacGillavry [22]. | P |

| Collaboratively contributed geospatial information (CCGI) (2007) | CCGI is a precursor to the term VGI, meaning user contributed geospatial information, which appeared in Bishr and Kuhn [23] and again in Keßler et al. [24]. CCGI implies collaboration between individuals while VGI has more of an individual component based on the views of Goodchild—see the definition of VGI below. | I |

| Contributed Geographic Information (CGI) (2013) | Harvey [10] distinguishes between CGI and VGI where CGI refers to geographic information “that has been collected without the immediate knowledge and explicit decision of a person using mobile technology that records location” whereas VGI refers to geographic information collected with the knowledge and explicit decision of a person. In VGI, data are collected using an “opt-in” agreement (e.g., OpenStreetMap and Geocaching where users choose to actively participate) in contrast to contributed CGI where data are collected via an “opt-out” agreement (e.g., cell phone tracking, RFID-enabled transport cards, other sensor data). Since opt-out agreements are more open-ended and offer few possibilities to control the data collection, this has implications for quality, bias assessment and fitness-for-use of the data in later analyses or in visualization. Harvey [10] raises issues such as data provenance, potential reuse of the data, privacy (both of the data and the location of the individual) and liability as key concerns for CGI. | I |

| Crowdsourcing (2006) | Crowdsourcing first appeared in Howe [4] where it was defined as a business practice in which an activity is outsourced to the crowd. The word crowdsourcing also implies a low cost solution, the involvement of large numbers of people and the fact that it has value as a business model. A classic example of a business-oriented crowdsourcing site is Amazon Mechanical Turk, which provides micro-payments to participants for undertaking small tasks, e.g., classification and transcription tasks [25]. More recently, Estellés-Arolas and González-Ladrón-de-Guevara [26] examined 32 definitions of crowdsourcing in the literature to produce a single definition as follows: “Crowdsourcing is a type of participative online activity in which an individual, an institution, a non-profit organization, or company proposes to a group of individuals of varying knowledge, heterogeneity, and number, via a flexible open call, the voluntary undertaking of a task. The undertaking of the task, of variable complexity and modularity, and in which the crowd should participate bringing their work, money, knowledge and/or experience, always entails mutual benefit. The user will receive the satisfaction of a given type of need, be it economic, social recognition, self-esteem, or the development of individual skills, while the crowdsourcer will obtain and utilize to their advantage what the user has brought to the venture, whose form will depend on the type of activity undertaken.” This definition emphasizes the online nature of the activity, which makes it narrower than other definitions in this table. Data collection in citizen science projects can be undertaken in the field or using paper forms. Moreover, not all crowdsourcing need be open to all but could be restricted geographically or to groups with certain expertise. Digital and educational divides also impose barriers on participation. Finally, crowdsourcing may not always entail mutual benefit if the data collected are then used for another purpose that differs from the one for which they were originally intended. | P |

| Extreme citizen science (2011) | Extreme citizen science can be attributed to Muki Haklay and his team at UCL (Excites). Extreme citizen science is at level 4 (or the highest level) of participation in the typology presented in Haklay [27]. Level 4 refers to collaborative science where the citizens participate heavily in, or lead on problem definition, data collection and analysis. It conveys the idea of a “completely integrated activity … where professional and non-professional scientists are involved in deciding on which scientific problems to work and on the nature of the data collection so that it is valid and answers the needs of scientific protocols while matching the motivations and interests of the participants. The participants can choose their level of engagement and can be potentially involved in the analysis and publication or utilisation of results.” Scientists have more of a role as facilitators or the project could be entirely driven and run by citizens. | P |

| Geocollaboration (2004) | First defined by MacEachren and Brewer [28] as “visually-enabled collaboration with geospatial information through geospatial technologies.” Geocollaboration involves two or more people to solve a problem or undertake a task together involving geographic information and a computer-supported environment. Tomaszewski [29] emphasizes that geocollaboration is multidisciplinary in nature, drawing upon human-computer interaction, computer science and psychology, and that it is a subset of the more general computer-supported collaborative work. | P |

| Geographic citizen science (2013) | Citizen science with a geographic or spatial context. The term appears in Haklay’s [27] chapter on typology of participation in citizen science and VGI. | P |

| GeoWeb (or GeoSpatialWeb) (or Geographic World Wide Web) (1994/2006) | The GeoWeb is the merging of spatial information with non-spatial attribute data on the web, which allows for spatial searching of the Internet. The concept (but not the actual term) was first outlined by Herring [30]. MacGuire [31] describes the GeoWeb 2.0 as the next step in the publishing, discovery and use of geographic data. It is a system of systems (GIS clients and servers, service providers, GIS portals, standards, collaboration agreements, etc.), which is very much in line with the idea of GEOSS (Global Earth Observation System of Systems). | P |

| Involuntary geographic information (iVGI) (2012) | This term first appeared in a paper by Fischer [32]. iVGI is defined as georeferenced data that have not been voluntarily provided by the individual and could be used for many purposes including mapping but also for more commercial applications such as geodemographic profiling. These type of data are usually generated in real-time from various kinds of social media. | I |

| Map Hacking/Map Hacks/Hackathons (and Appathons) (1999) | The term “hacker” has been used to refer to someone who tries to break into a computer system. A more positive use of the term is someone who can devise a clever solution to a programming problem; someone who generally enjoys programming; or someone who can appreciate good “hacks” [33]. The term “Map hacking” has been used quite specifically in relation to computer/video games in which a player executes a program that allows them to bypass obstacles or see more of what they should actually be allowed to see—essentially a type of cheating [34]. However, a positive usage relates to creating creative and useful solutions with digital maps, e.g., see the book called “Hacking Google Maps and Google Earth” or “Google Maps Hack” or “Mapping Hacks: Tips & Tools for Electronic Cartography”. Hackathons such as “Random Hacks of Kindness” have resulted in geospatial solutions in the area of post-disaster response. Appathons are now appearing with a particular emphasis on developing mobile applications. | P |

| Mashup (1999 or around time of Web 2.0) | The term mashup was borrowed from the music industry where it originally denoted a piece of music that had been created by blending two or more songs. In a geographic context, a mashup is the integration of geographic information from sources that are distributed across the Internet to create a new application or service [35]. Mashup can also refer to a digital media file that contains a combination of elements including text, maps, audio, video and animation, to effectively create a new, derivative work for the existing pieces. | P |

| Neogeography (2006) | Neogeography has been defined by Turner [3] as the making and sharing of maps by individuals, using the increasing number of tools and resources that are freely available. Implicit in this definition is the movement away from traditional map making by professionals. The definition of neogeography by Szott [36,37] encompasses broader practices than GIS and cartography and includes everything that falls outside of the professional domain of geographic practices. | P |

| Participatory sensing (2006) | Participatory sensing was introduced by Burke et al. [38] as the use of mobile devices deployed as part of an interactive participatory sensor network which can be used to collect data and share knowledge. The data and knowledge can then be analyzed and used by the public or by more professional users. Examples include noise levels collected by built-in microphones and photos taken by mobile devices which can be used to gather environmental data. Often used together with environmental monitoring and recently developed by Karatzas [39]. | P |

| Public participation in scientific research (PPSR) (2009 for Bonney et al. review [38] but is most likely older) | PPSR was reviewed by Bonney et al. [40] in relation to informal science education. PPSR is defined as “public involvement in science including choosing or defining questions for the study; gathering information and resources; developing hypotheses; designing data collection and methodologies; collecting data; analyzing data; interpreting data and drawing conclusions; disseminating results; discussing results and asking new questions.” Bonney et al. [40] categorize PPSR projects into three main types: contributory (mostly data collection); collaborative (data collection and refining project design, analyzing data, disseminating results; and co-created (designed together by scientists and the general public where the public inputs to most or all of the steps in the scientific process). PPSR appears to be equivalent to citizen science, with the typology defined by Bonney et al. [40] mapping fairly closely onto that of Haklay [27]. | P |

| Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS) (1996) | The term PPGIS (Public Participation Geographic Information Systems) has its origins in a workshop organized by the National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis (NCGIA) in Orono, Maine USA, on 10–13 July 1996. PPGIS are a set of GIS applications that facilitate wider public involvement in planning and decision making processes [41]. PPGIS has been identified as relevant in processes of urban planning, nature conservation and rural development, among others. | P |

| Science 2.0 (2008) | Coined by Shneiderman [42], the term Science 2.0 refers to the next generation of collaborative science enabled through IT, the Internet and mobile devices, which is needed to solve complex, global interdisciplinary problems. Citizens are one component of Science 2.0. | P |

| Swarm Intelligence (2011 but may be older) | Appears in Bücheler and Sieg [43] as a “buzzword” for paradigms like citizen science, crowdsourcing, open innovation, etc. From an Artificial Intelligence (AI) perspective, however, swarm intelligence refers to a set of algorithms that use agents (or boids) and simple rules to generate what appears to be intelligent behavior. These algorithms are often used for optimization tasks and often rules for success in various contexts are derived from the emergent behaviours observed. | P |

| Ubiquitous cartography (2007) | Defined in Gartner et al. [44] as “… the study of how maps can be created and used anywhere and at any time.” This term emphasizes the idea of real-time, in situ map production versus more traditional cartography and covers other domains such as location-based services and mobile cartography. | P |

| User-created content (UCC) User-generated content (UGC) (2007 but likely older) | UCC/UGC arose from web publishing and digital media circles. It consists of users who publish their own content in a digital form (e.g., data, videos, blogs, discussion forum postings, images and photos, maps, audio files, public art, etc.) [45]. Other synonyms for UCC/UGC are peer production and consumer generated media. More recently, Krumm et al. (2008) refer to “pervasive UGC” where UGC moves from the desktop into people’s lives, e.g., through mobile devices. | I |

| Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) (2007) | First coined by Goodchild (2007), VGI is defined as “the harnessing of tools to create, assemble, and disseminate geographic data provided voluntarily by individuals”. In Schuurman (2009), Goodchild argues that crowdsourcing implies a kind of consensus-producing process and the assumption that several people will provide information about the same thing so it will be more accurate than VGI. VGI, on the other hand, is produced by individuals without any such opportunity for convergence. Elwood et al. (2012) define VGI as spatial information that is voluntarily made available, with an aim to provide information about the world. | I |

| Web mapping (Mid-nineties) | A term used in parallel with the development of web-based GIS solutions, which has recently evolved to mean “the study of cartographic representation using the web as the medium, with an emphasis on user-centered design (including user interfaces, dynamic map contents, and mapping functions), user-generated content, and ubiquitous access” and appears in Tsou [46]. | P |

| Wikinomics (2006) | The name of a book by Tapscott and Williams [47], wikinomics embodies the idea of mass collaboration in a business environment. It is based on four principles: (a) openness; (b) peering (or a collaborative approach); (c) sharing; and (d) acting globally. The book itself is meant to be a collaborative and living document that everyone can contribute to. | P |

| Subject | Description |

|---|---|

| Communications | Providing IP addresses, mobile cell ids, wireless networks |

| Crime/Public Safety | Map showing reported crimes |

| Disasters (natural and man-made) | Mapping after a natural or manmade disaster |

| Ecology | Species identification, reporting of roadkill, species counts |

| Education | Environmental monitoring in schools, e.g., through the GLOBE (Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment) program, where the primary focus is education |

| Environmental monitoring | Water levels and quality |

| Feature mapping | Mapping of buildings, other features of interest |

| Fishing | Fishing hotspots, stories, community building |

| Gazetteer | Place name site |

| Geocaching | Geocaching is an outdoor location-based treasure hunting game (http://www.geocaching.com). |

| Hiking/Trails | Trail guides, GPS trails plotted on a map/mobile device |

| Land cover | Satellite and photograph classification by volunteers, e.g., Geo-Wiki and Picture Pile |

| Location-based social media | Sites that bring together people in close proximity, photo sharing sites, georeferenced check-in data, which has been used for mapping natural cities, etc. |

| Mobile data/Behavior | Used to target customers by location |

| Search engine data | Google Trends, e.g., Google applications for monitoring trends in flu and dengue fever using archive of search data |

| Sky/Stars | Identification of stars, condition of the sky |

| Places of interest/Travel | Stories (text and video) and photos of places of interest; travel guides; travel advice |

| Transport | Navigation, real-time traffic, cycle routes, speed traps, mapping of roads |

| Weather | Weather data collection, snow depths, avalanches |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

See, L.; Mooney, P.; Foody, G.; Bastin, L.; Comber, A.; Estima, J.; Fritz, S.; Kerle, N.; Jiang, B.; Laakso, M.; et al. Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5050055

See L, Mooney P, Foody G, Bastin L, Comber A, Estima J, Fritz S, Kerle N, Jiang B, Laakso M, et al. Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2016; 5(5):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5050055

Chicago/Turabian StyleSee, Linda, Peter Mooney, Giles Foody, Lucy Bastin, Alexis Comber, Jacinto Estima, Steffen Fritz, Norman Kerle, Bin Jiang, Mari Laakso, and et al. 2016. "Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 5, no. 5: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5050055

APA StyleSee, L., Mooney, P., Foody, G., Bastin, L., Comber, A., Estima, J., Fritz, S., Kerle, N., Jiang, B., Laakso, M., Liu, H.-Y., Milčinski, G., Nikšič, M., Painho, M., Pődör, A., Olteanu-Raimond, A.-M., & Rutzinger, M. (2016). Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 5(5), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5050055