Flood Susceptibility and Risk Assessment in Myanmar Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Interpretable Ensemble Machine Learning Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

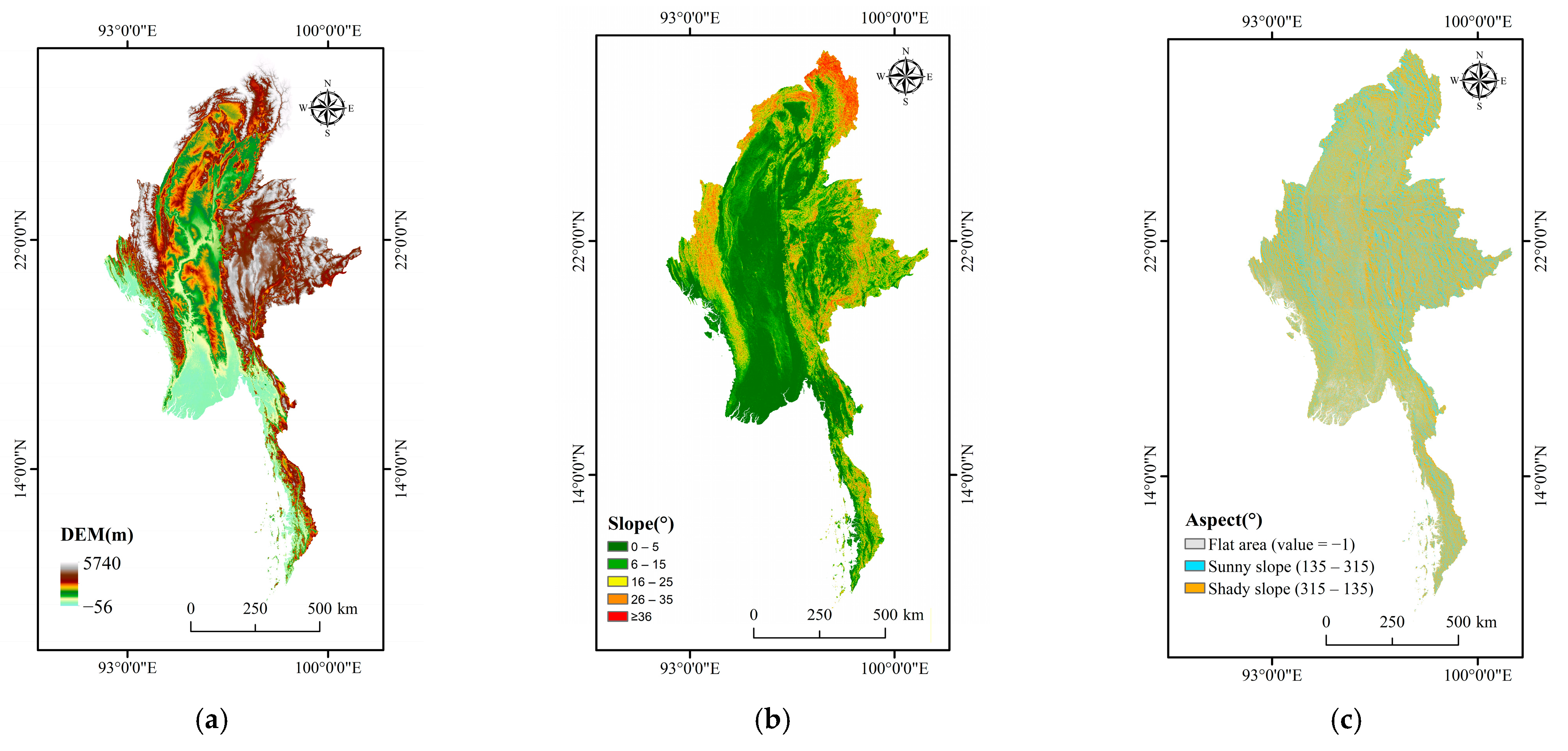

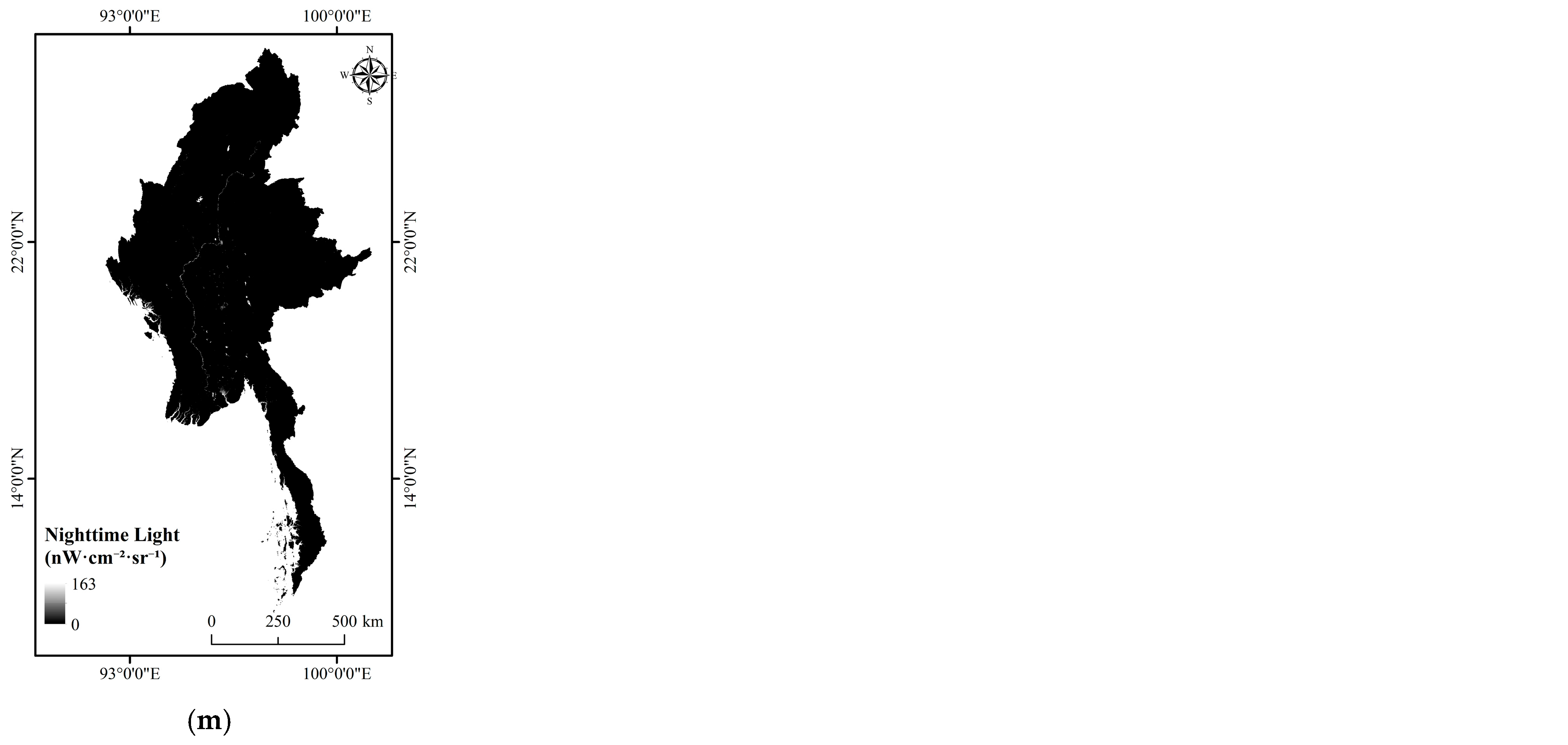

2.2. Data Sources and Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Data Sources

2.2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Technical Workflow

2.4. Machine-Learning Models

2.4.1. XGBoost

2.4.2. LightGBM

2.5. Performance Evaluation Metrics and Validation Strategy

2.5.1. Precision

2.5.2. Recall

2.5.3. F1-Score

2.5.4. Accuracy

2.5.5. ROC Curve

2.5.6. Jaccard Index

2.5.7. Adjusted Accuracy

2.6. SHAP-Based Feature Importance Analysis Methodology

3. Results

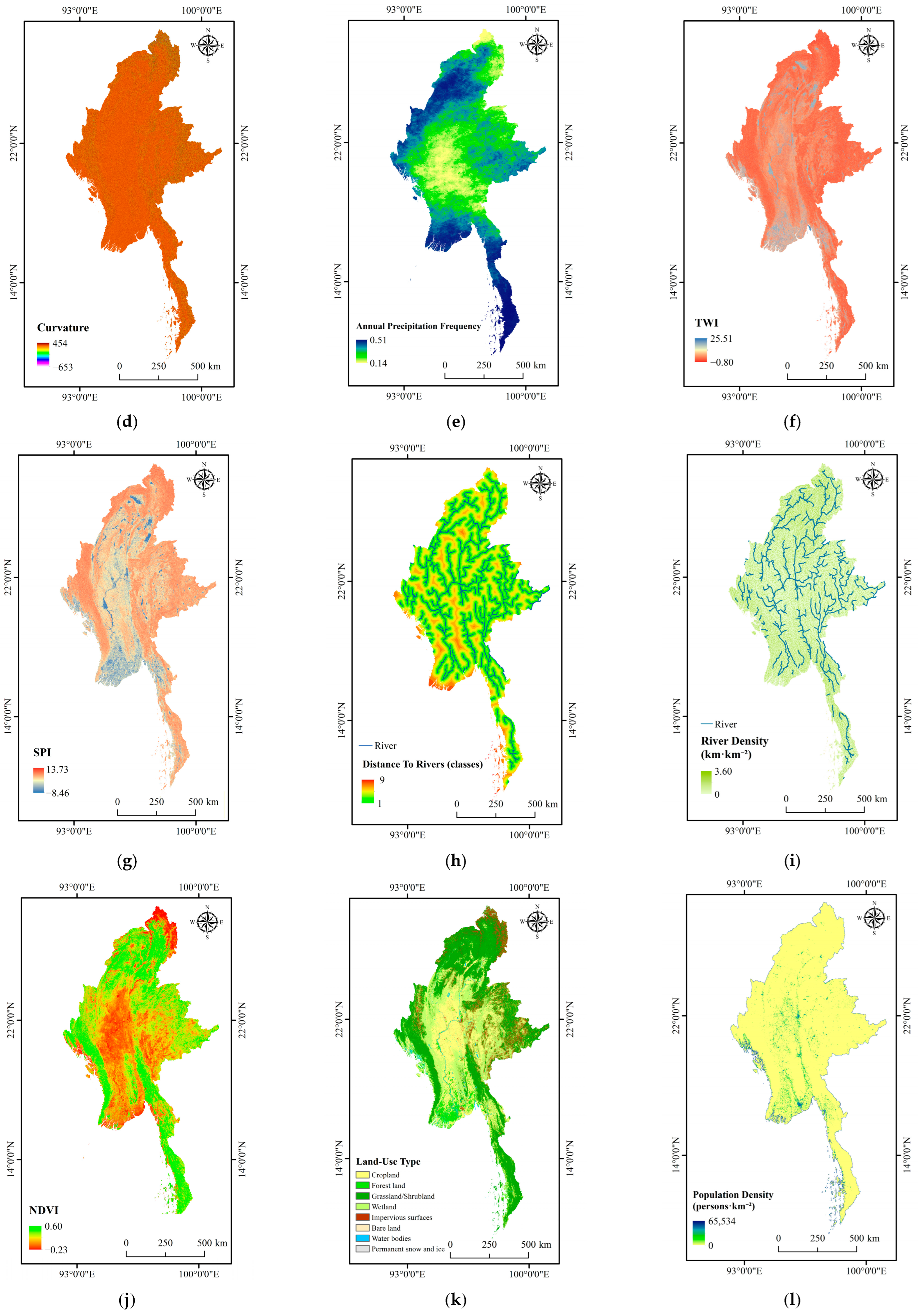

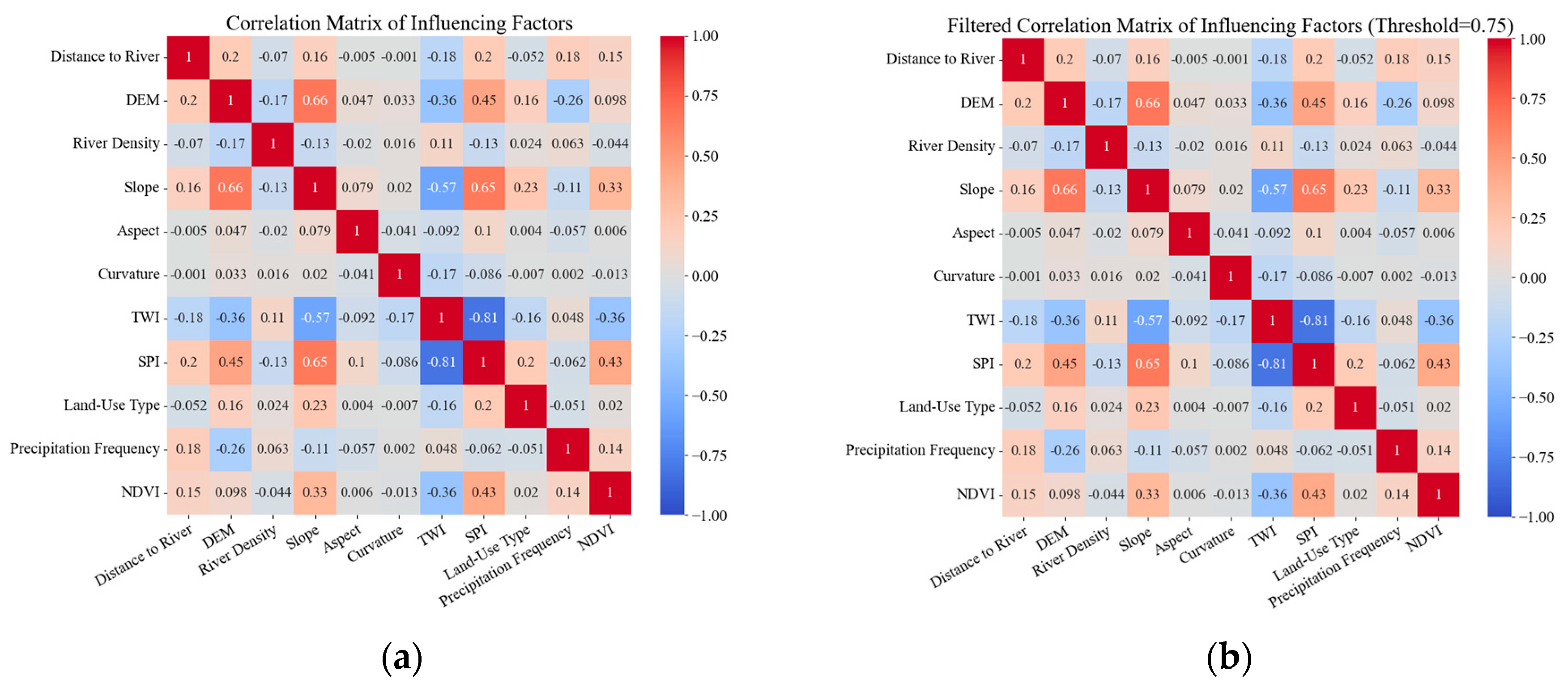

3.1. Correlation Analysis of Influencing Factors

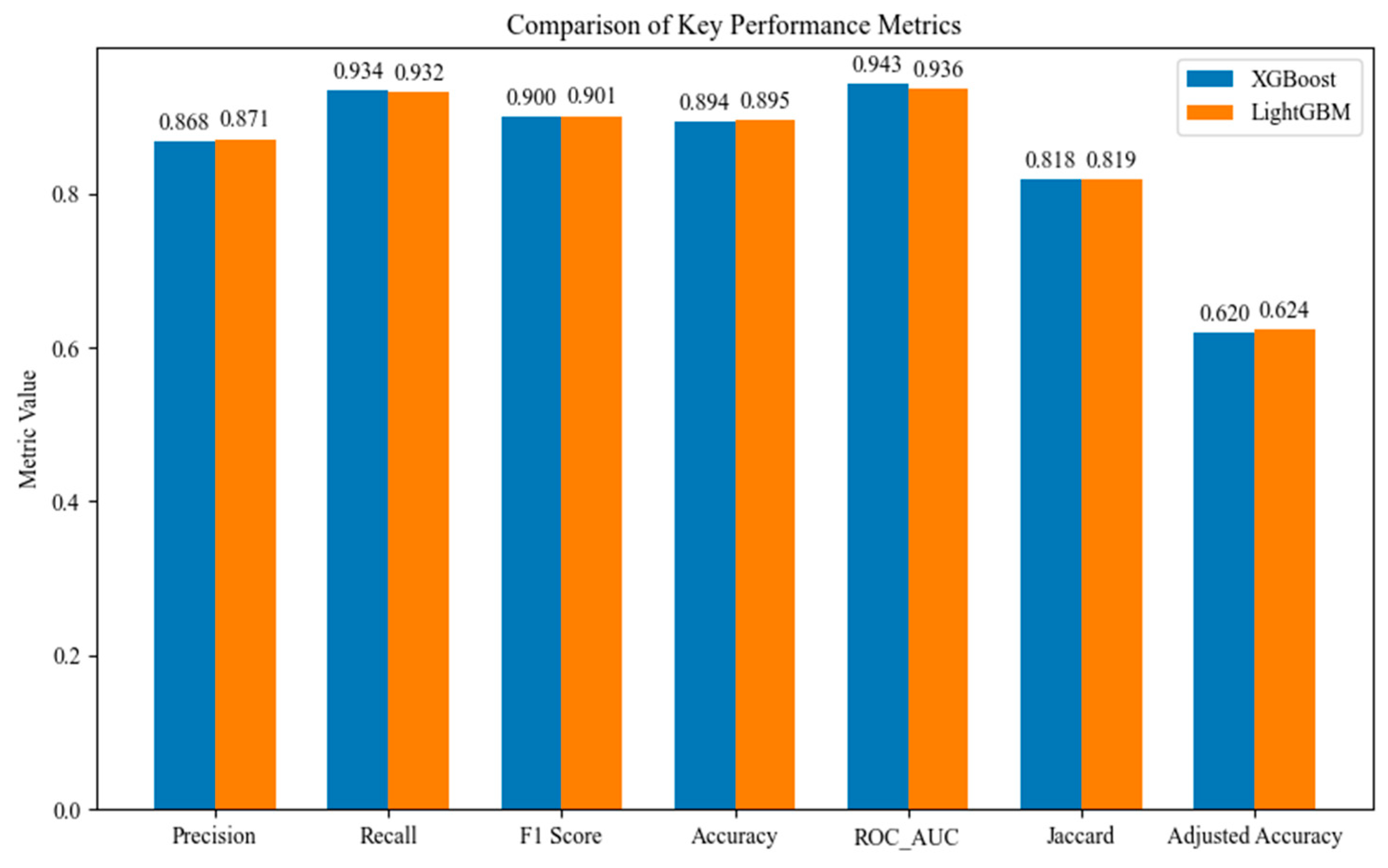

3.2. Evaluation of Predictive Performance

3.2.1. Comparison of Model Performance

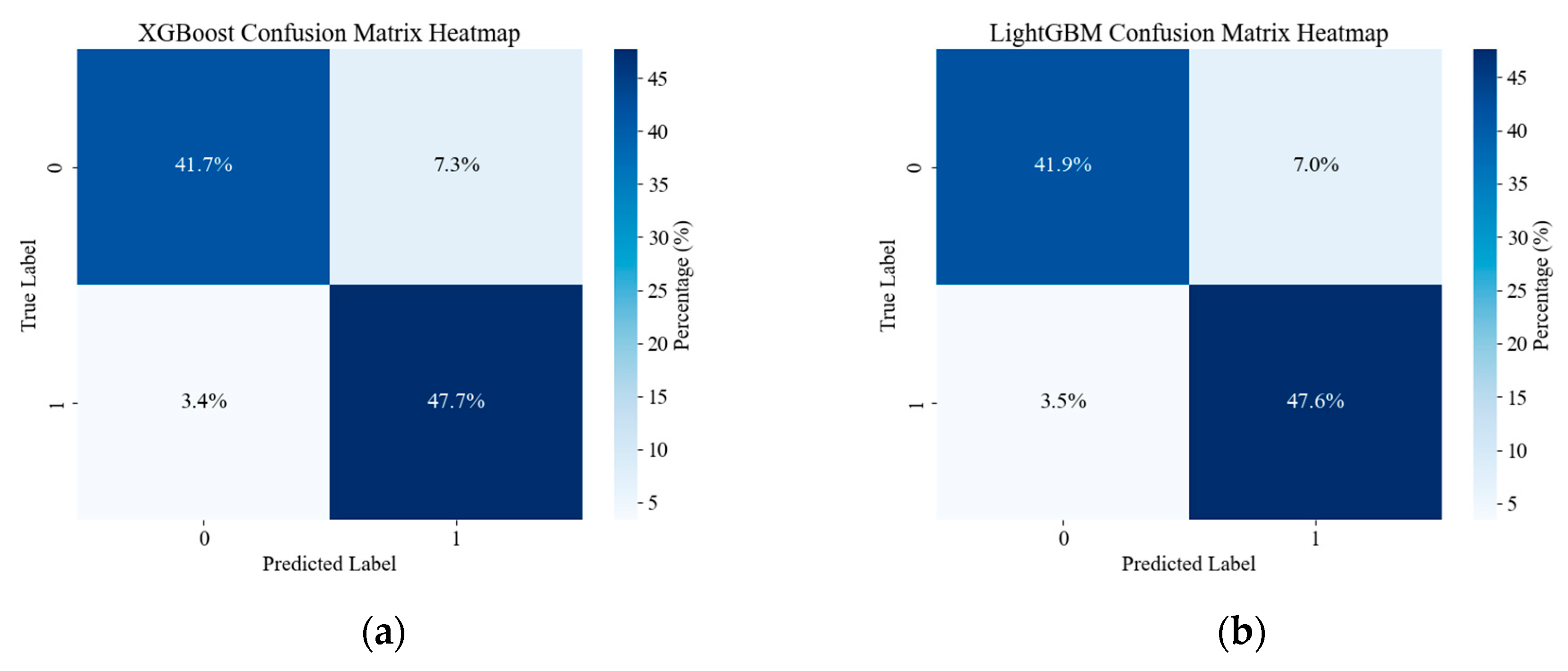

3.2.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

3.2.3. ROC Curve Analysis

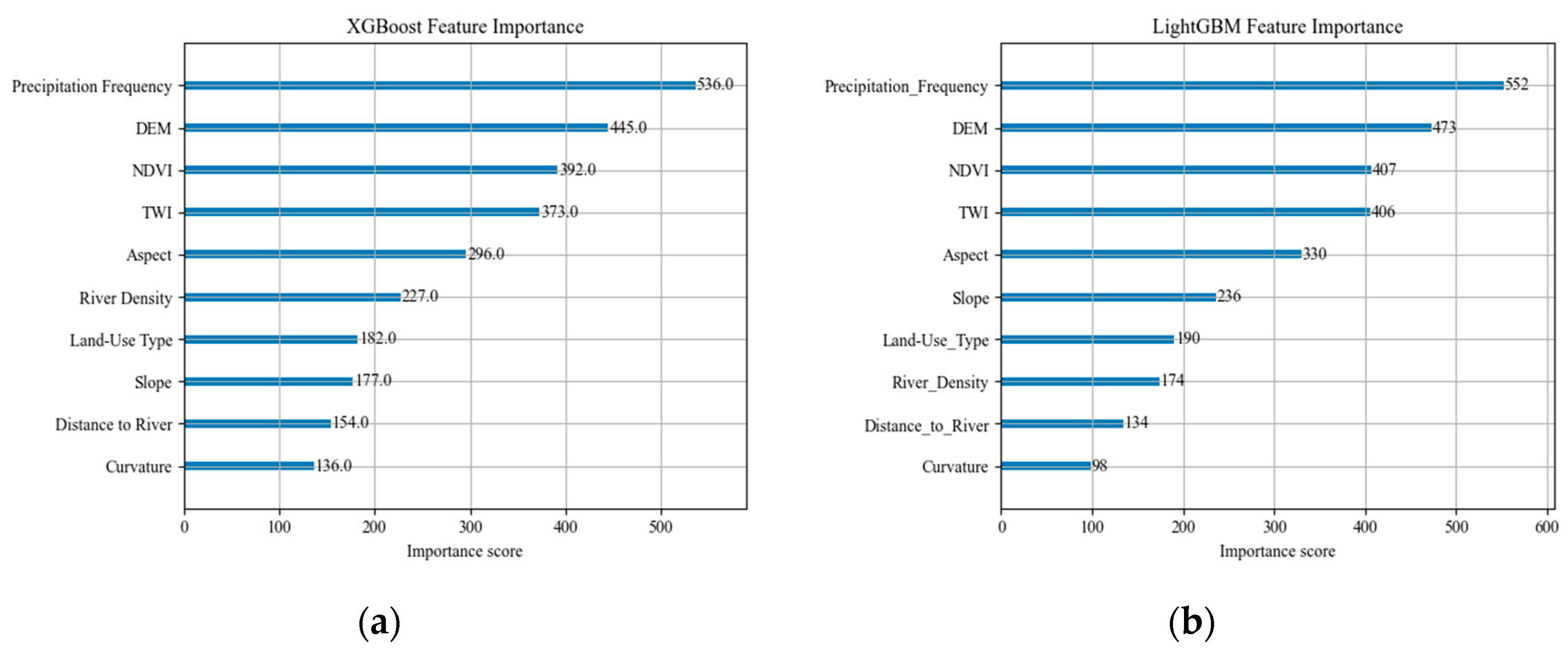

3.3. Feature Importance Analysis

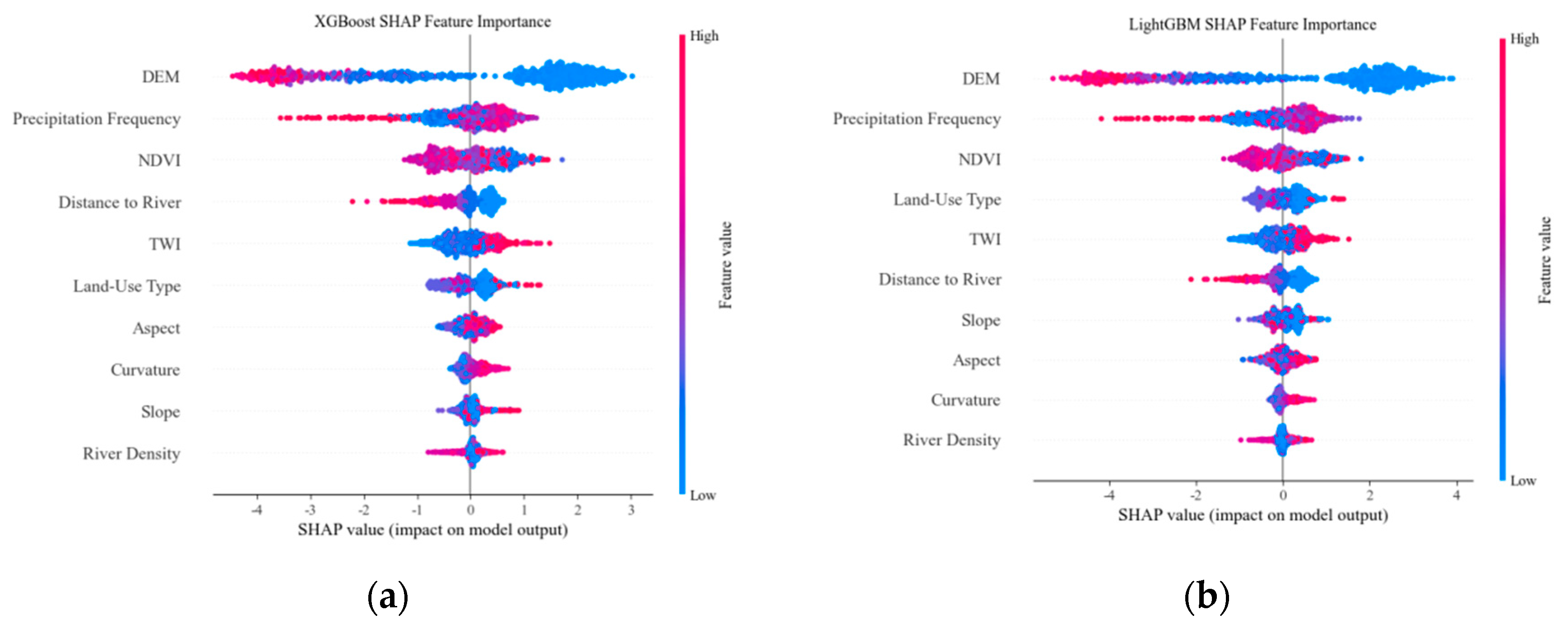

3.3.1. Evaluation of Feature Importance

3.3.2. Analysis of Model Predictive Power

3.4. Spatial Distribution of Flood Susceptibility

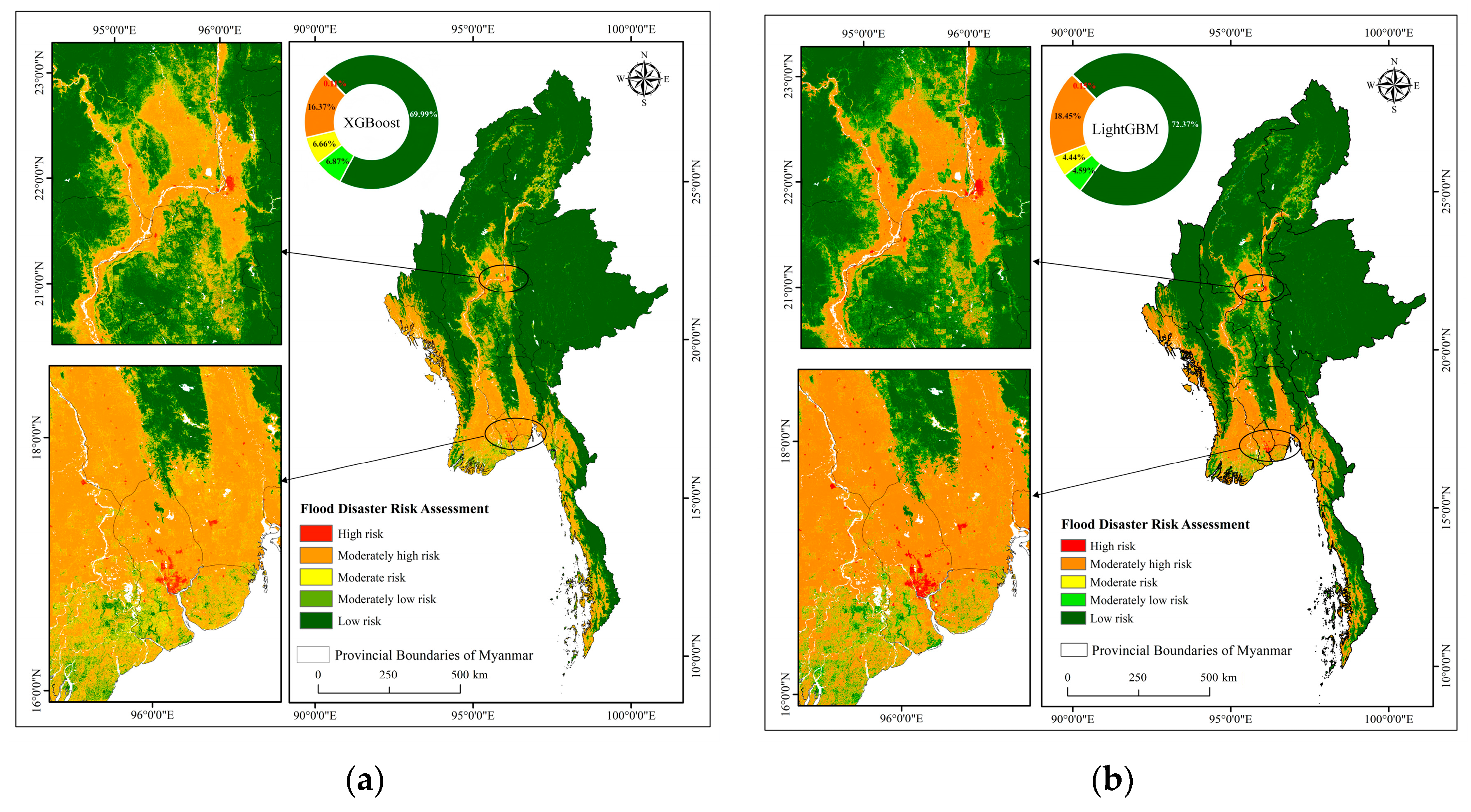

3.5. Flood Disaster Risk Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S. Flood disaster prediction and risk assessment based on data analysis and machine learning. Inf. Technol. Informatiz. 2024, 8, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR); Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019); United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/human-cost-disasters-overview-last-20-years-2000–2019 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Wei, X.K. Study on Runoff Variation Prediction Based on Multiple Deep Learning Methods. Ph.D. Dissertation, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarian, H.; Gheibi, M.; Hajiaghaei Keshteli, M.; Rahmani, M. A hybrid novel framework for flood disaster risk control in developing countries based on smart prediction systems and prioritized scenarios. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Myanmar Floods and Landslides: Post Disaster Needs Assessment; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/myanmar/publication/myanmar-floods-and-landslides-post-disaster-needs-assessment (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Varra, G.; Della Morte, R.; Tartaglia, M.; Fiduccia, A.; Zammuto, A.; Agostino, I.; Booth, C.A.; Quinn, N.; Lamond, J.E.; Cozzolino, L. Flood susceptibility assessment for improving the resilience capacity of railway infrastructure networks. Water 2024, 16, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edamo, M.L.; Ukumo, T.Y.; Lohani, T.K.; Dile, Y.T.; Tefera, Z.M. A comparative assessment of multi-criteria decision-making analysis and machine learning methods for flood susceptibility mapping and socio-economic impacts on flood risk in the Abela–Abaya floodplain of Ethiopia. Environ. Chall. 2022, 9, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, L.; Elabed, A.; El Khanchoufi, A. Multidimensional risk assessment based on flood susceptibility mapping and multiple socioeconomic variables under climate change. Sci. Afr. 2025, 28, e02834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Thapa Chhetri, M.; Bloetscher, F.; Yong, Y.; Su, H. Semi-automated workflow for multi-basin, multi-scenario flood risk modeling, mapping, and impact assessment. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 14425–14441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardane, P.; Rajapakse, L.; Siriwardana, C. Integrated flood risk management for urban resilience: A multi-method framework combining hazard mapping, hydrodynamic modelling, and economic impact assessment. Resilient Cities Struct. 2025, 4, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Singh, S.K.; Kanga, S.; Sajan, B.; Meraj, G.; Kumar, P. Advancing flood risk assessment through integrated hazard mapping: A Google Earth Engine-based approach for comprehensive scientific analysis and decision support. J. Clim. Change 2024, 10, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibandze, P.; Kalumba, A.M.; Aljaddani, A.H.; Zhou, L.; Afuye, G.A. Geospatial mapping and meteorological flood risk assessment: A global research trend analysis. Environ. Manag. 2025, 75, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, K.; Minderhoud, P.S.J.; Peffeköver, A.; Vogel, A.; Brückner, H.; Kraas, F.; Oo, N.W.; Brill, D. Assessing land elevation in the Ayeyarwady Delta (Myanmar) and its relevance for studying sea level rise and delta flooding. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 2257–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; He, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, S. Effects of climate change on the estimation of extreme sea levels in the Ayeyarwady Sea of Myanmar by Monte Carlo simulation. Water 2025, 17, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latt, Z.Z.; Wittenberg, H. Hydrology and flood probability of the monsoon-dominated Chindwin River in northern Myanmar. J. Water Clim. Change 2015, 6, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Seeger, K.; Brill, D.; Brückner, H.; Kyaw, A.; Myint, Z.N.; Kraas, F. Towards integrated flood management: Vulnerability and flood risk in the Ayeyarwady Delta of Myanmar. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, N.; Bhattacharjee, N.; Sarmah, N.; Nath, M.J. Estimation of flood hazard zones of Noa River Basin using maximum entropy model in GIS. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2025, 24, B4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Bates, P.D.; Wing, O.; Sampson, C.; Quinn, N.; Neal, J. New estimates of flood exposure in developing countries using high-resolution population data. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, K. Measurement of urban spatial structure and its influencing factors in China based on nighttime light data. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2025, 41, 47–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Grill, G. Global river hydrography and network routing: Baseline data and new approaches to study the world’s large river systems. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, L.; Usha, T.; Gowrappan, M.; Kasthuri, B.P.; Moorthy, P.; Chokkalingam, L. Flood susceptibility analysis in Chennai Corporation using frequency ratio model. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2021, 49, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJuaidi, A.E.M. The interaction of topographic slope with various geo-environmental flood-causing factors on flood prediction and susceptibility mapping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 59327–59348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xi, S.; Chen, X.; Lian, Y. Quantification of multiple climate change and human activity impact factors on flood regimes in the Pearl River Delta of China. Adv. Meteorol. 2016, 2016, 3928920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhong, S.; Ge, Y.; Lin, H.; Chang, L.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, C.; Altan, O. Evaluating the Performance of SDGSAT-1 GLI Data in Urban Built-Up Area Extraction from the Perspective of Urban Morphology and City Scale: A Case Study of 15 Cities in China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 17166–17180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.B.; Kang, Y.; Song, X.Y.; Wang, X.J.; Jin, J.L. Principles and Applications of Univariate Hydrological Series Frequency Calculation; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 631–652. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wan, Z.; Borjigin, S.; Zhang, D.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, R.; Gao, Q. Changing trends of NDVI and their responses to climatic variation in different types of grassland in Inner Mongolia from 1982 to 2011. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Y. Vegetation restoration in response to climatic and anthropogenic changes in the Loess Plateau, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.N.; Zhao, S.Y.; Gu, J.Z. Correlation analysis between vegetation coverage and climate drought conditions in North China during 2001–2013. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.Y.L.; Leow, S.M.H.; Bea, K.T.; Cheng, W.K.; Phoong, S.W.; Hong, Z.-W.; Chen, Y.-L. Mitigating the Multicollinearity Problem and Its Machine Learning Approach: A Review. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, A.; Praitis Hill, K. Additional Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors: Extending O’Brien to the Context of Specification Error. Qual. Quant. 2024, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanek, R. Daily streamflow forecasting in mountainous catchment using XGBoost, LightGBM and CatBoost. Hydrology 2022, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.; Li, D.F.; Li, W.Z.; Fang, Z.N. Data-driven flood alert system (FAS) using extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) to forecast flood stages. Water 2022, 14, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarayan, S.; Devanantham, A.; Nagireddy Masthan, R.; Parthasarathy, K.S.S.; Janardhanam, N.; Subbarayan, S.; Vivek, S. Flood susceptibility mapping using machine learning boosting algorithms techniques in Idukki District of Kerala, India. Urban. Clim. 2023, 49, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu El Magd, S.A.; Pradhan, B.; Alamri, A. Machine learning algorithm for flash flood prediction mapping in Wadi El-Laqeita and surroundings, Central Eastern Desert, Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Han, Z.T.; Xu, H.S.; Bin, L.L. Rapid prediction model for urban floods based on a light gradient boosting machine approach and hydrological–hydraulic model. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2023, 14, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei Kyei, R.; Ampratwum, G.; Komac, U.; Narbaev, T. Critical analysis of the emerging flood disaster resilience assessment indicators. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2025, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, X.R. Analysis of influencing factors of terrestrial carbon sinks in China based on LightGBM model and Bayesian optimization algorithm. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.; Motamedvaziri, B.; Khaleghi, M.R.; Ahmadi, H. Spatial prediction of flood susceptible areas using machine learning methods in the Siahkhor Watershed of Kermanshah Province. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnodębska, K.; Goch, W.; Uhl, J.H.; Verstegen, J.A.; Pesaresi, M. Advancing precision, recall, F-score, and Jaccard index: An approach for continuous, ratio-scale measurements. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 193, 106614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, A.; Carrasco, A.; Martín, A.; de las Heras, A. The impact of class imbalance in classification performance metrics based on the binary confusion matrix. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 91, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Lee, S.; Dikshit, A.; Kim, H. Spatial flood susceptibility mapping using an explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) model. Geosci. Front. 2023, 14, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.; Ayzel, G.; de Souza, A.C.T.; Bronstert, A.; Heistermann, M. Towards urban flood susceptibility mapping using data-driven models in Berlin, Germany. Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk 2022, 13, 1640–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; Li, H.E.; Zhou, N.; Wang, X.B.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z. Study on characteristics, mechanisms, and adaptive countermeasures of catastrophic dam-break disasters under climate change. J. Hydraul. Waterw. Eng. 2025, 5, 14–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Herath, P.; Prinsley, R.; Croke, B.; Vaze, J.; Pollino, C. A bibliometric analysis and overview of the effectiveness of Nature-based Solutions in catchment scale flood mitigation. Nat.-Based Solut. 2025, 7, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Huang, M.; Lin, H.; Ge, Y.; Zhu, D.; Gong, D.; Altan, O. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Ecological Environment Quality in Arid and Sandy Regions with a Particular Remote Sensing Ecological Index: A Study of the Beijing-Tianjin Sand Source Region. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.A.; Chen, Z.; Pradhan, B.; Meena, S.R.; Zhou, Y. Hybrid heterogeneous ensemble learning framework for flood susceptibility mapping in Balochistan, Pakistan. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, S. Research on Flood Occurrence Prediction Based on Entropy Weighted TOPSIS and Ensemble Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Workshop on Materials Engineering and Computer Sciences (IWMECS); Francis Academic Press: London, UK, 2024; pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Sources | Resolution/Year | Purpose | Acquisition Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topographic Data | ASTER GDEM V3 (30 m) Dataset | 30 m/2020 | Extract elevation, slope, aspect, TWI, SPI factors | http://www.Gscloud.cn (accessed on 1 October 2025) |

| Meteorological Data | UCSB-CHG/CHIRPSDataset | 30 m/2020–2024 | Extract annual precipitation frequency | Google Earth Engine Platform |

| Land Use Data | GLC_FCS30-2020 | 30 m/2020 | Analyze the impact of 14 land cover types on flooding | https://data.casearth.cn (accessed on 1 October 2025) |

| River Data | HydroRIVERS (WWF) Global River Dataset [17] | 30 m/2024 | Extract river density and distance | https://hydrosheds.org (accessed on 1 October 2025) |

| NDVI | LANDSAT/LC08/C02/T1_L2 Dataset | 30 m/2020–2024 | Characterize vegetation cover status | Google Earth Engine Platform |

| Historical Flood Imagery | UNOSAT Flood Imagery | 30 m/2020–2024 | Flood extent calibration and model validation | https://unosat.org/products (accessed on 1 October 2025) |

| Socioeconomic Data | LandScan Global Population Database [18] | 500 m/2024 | Extract population density | https://landscan.ornl.gov (accessed on 1 October 2025) |

| Global Scale Nightlight Time Series Dataset [19] | 500 m/2024 | Characterize socio-economic development level | https://github.com/eoatlas/nightlight (accessed on 1 October 2025) |

| Preprocessing Step | Method/Tool | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Data Cleaning | Manual inspection/Linear interpolation (GEE) | Missing and abnormal values were removed. NDVI gaps caused by cloud cover were filled using linear interpolation. Incomplete socioeconomic records were excluded. |

| Spatial Registration | ArcMap 10.8 | All datasets were reprojected to the GCS_WGS_1984 coordinate system and resampled to a spatial resolution of 30 m (except for population and nighttime light data). |

| Normalization | Min-max normalization | Influencing factors (e.g., DEM, Precipitation, NDVI) were scaled to a [0, 1] range to eliminate dimensional inconsistencies. |

| Multicollinearity Analysis | Pearson correlation coefficient/Variance Inflation Factor (VIF, Python 3.8) | Highly correlated influencing factors were identified using Pearson correlation analysis and VIF. Variables with |r| ≥ 0.75 or VIF > 10 were considered redundant and removed to reduce multicollinearity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X. Flood Susceptibility and Risk Assessment in Myanmar Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Interpretable Ensemble Machine Learning Model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010045

Lu Z, Tian Z, Zhang H, Lu Y, Chen X. Flood Susceptibility and Risk Assessment in Myanmar Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Interpretable Ensemble Machine Learning Model. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Zhixiang, Zongshun Tian, Hanwei Zhang, Yuefeng Lu, and Xiuchun Chen. 2026. "Flood Susceptibility and Risk Assessment in Myanmar Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Interpretable Ensemble Machine Learning Model" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010045

APA StyleLu, Z., Tian, Z., Zhang, H., Lu, Y., & Chen, X. (2026). Flood Susceptibility and Risk Assessment in Myanmar Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Interpretable Ensemble Machine Learning Model. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010045