The research methodology of this study consists of two main components: the research process and the conceptual framework. The research process outlines the overall procedures, encompassing preliminary planning, experimental design, data collection, and statistical analysis. The conceptual framework, on the other hand, illustrates the logical relationships among the research variables, providing the theoretical basis for hypothesis formulation and subsequent statistical testing.

In the research process, the study first established its research objectives and questions, then designed VR instructional materials for mountaineering education and developed corresponding teaching materials for the control group to facilitate comparative instruction. The process encompasses participant selection, instructional implementation, data collection, and results analysis, ensuring that the overall research design is systematic and replicable. The research framework is grounded in educational psychology and multimedia learning theory, integrating theories on VR applications in education, learning motivation, and cognitive load to develop the conceptual model and formulate the research hypotheses. This framework helps clarify the relationships among variables and provides the theoretical foundation for subsequent statistical validation.

3.3. Research Tools and Instructional Design

The traditional teaching materials consisted mainly of researcher-developed PowerPoint slides and instructional videos, supplemented by in-class explanations and practice exercises. The course content covered topics such as orientation, map reading, compass operation, magnetic declination, and the resection method. Instruction was delivered using slides and teacher explanations to help students understand fundamental concepts of mountaineering through traditional teaching methods.

Figure 4 depicts the class presentation interface, with learning content systematically organized as follows:

- (1)

Orientation: Introduction to the cardinal directions (East, South, West, North) and their English abbreviations.

- (2)

Map: Overview of map symbols, contour lines, and grid lines.

- (3)

Compass: Description of the compass structure and instructions for its proper use.

- (4)

Magnetic Declination: Explanation of the difference between geographic (true) north and magnetic north.

- (5)

Resection Method: Determination of one’s position using a map and bearing lines.

The traditional instructional materials were developed based on Ordnance Survey map education guides [

29] to align with international map-reading standards, covering scale, grid lines, contour lines, compass operation, and magnetic declination correction. The VR system was implemented using a Meta Quest 2 headset paired with a computer, ensuring stable operation and an immersive learning experience. Development was carried out in Unity game engine 2022.3.44f1 with the Universal Render Pipeline (URP) for optimized performance and visual fidelity. Terrain heightmaps were generated using the Cities: Skylines Map Generator [

39] to test terrain modeling approaches in Unity game engine (

Figure 5). Although not included in the final instructional materials, this process provided critical insights into terrain modeling for educational purposes.

The Unity Gaia plugin 4.1.3 was assessed for terrain and vegetation generation (

Figure 6), but it was not included in the final version of the instructional materials. The final instructional scenes were constructed using Unity’s built-in Terrain system and the URP Demo scene, enhanced by a custom map-drawing tool generating contour lines, grids, elevation data, and river features, enabling seamless integration with the map-reading module.

The custom map-drawing tool developed for this study can merge multiple terrains and automatically generate contour lines, grids, elevation data, and water bodies. Its primary function is the conversion of 3D terrain into a 2D representation resembling standard topographic maps, making it particularly suitable for use in mountaineering education materials. The generated map was produced at a scale of 1:12,500, where 1 cm on the map corresponds to 125 m in reality. To support map-reading and positioning exercises, grid intervals were set to 1000 m (approximately 8 × 8 cm on the map), as shown in

Figure 7. This design closely mirrors conventional topographic maps, enabling students to effectively practice positioning, orientation, and distance estimation skills.

The tool allows rapid regeneration of maps to meet instructional needs. Because the 2D maps are derived directly from Unity’s terrain data, any modification to the 3D environment—such as adding ridges, lakes, or slopes—can immediately produce an updated 2D map. This capability significantly enhances the flexibility and efficiency of developing instructional materials. To illustrate the correspondence between the 2D maps and Unity’s 3D environment,

Figure 8 presents a top-down view of the Unity scene, showing how the 2D maps were generated from the underlying 3D terrain.

In addition to the map-drawing tool, two supplementary tools were developed to enhance interactivity and learning outcomes. Implemented in Unity game engine, the quiz tool in

Figure 9a enables embedding multiple-choice questions related to the course content within VR instructional materials. It provides immediate feedback by displaying a positive cue for correct answers and disabling incorrect options until the correct one is selected, reinforcing conceptual understanding and discouraging rote memorization. The page-flipping tool in

Figure 9b allows teachers or students to navigate slides within the VR environment using buttons or keyboard shortcuts. It can present text, images, and key points in a structured format similar to traditional teaching materials.

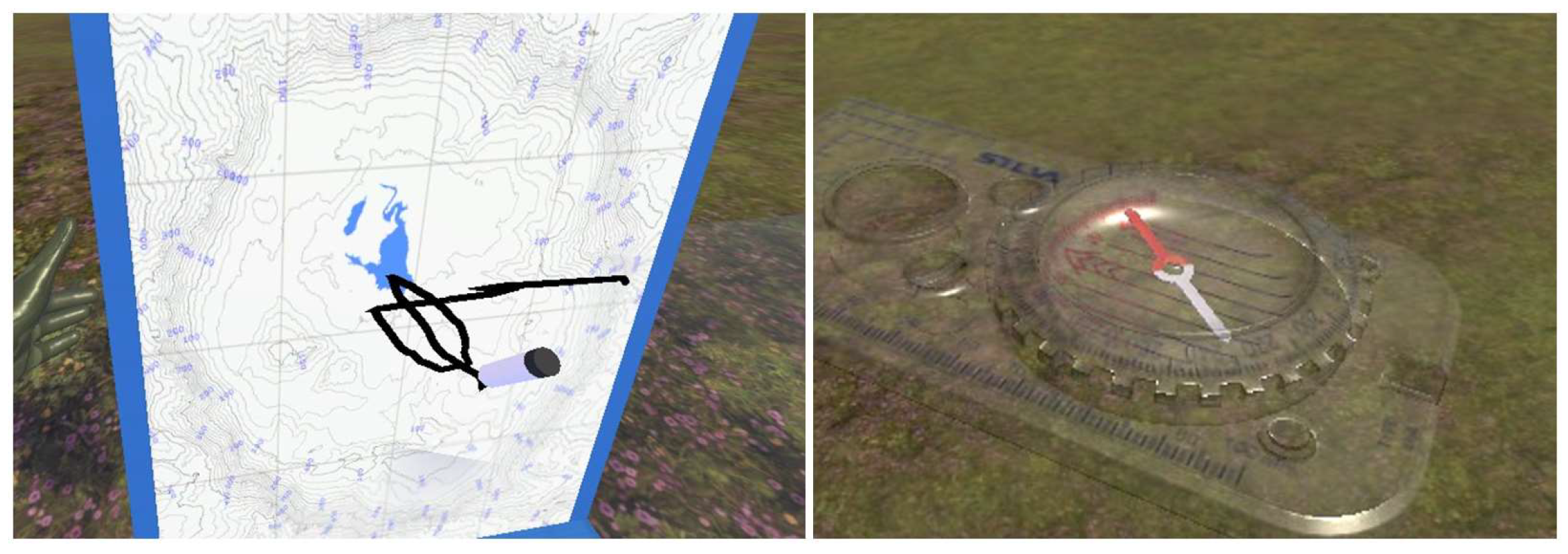

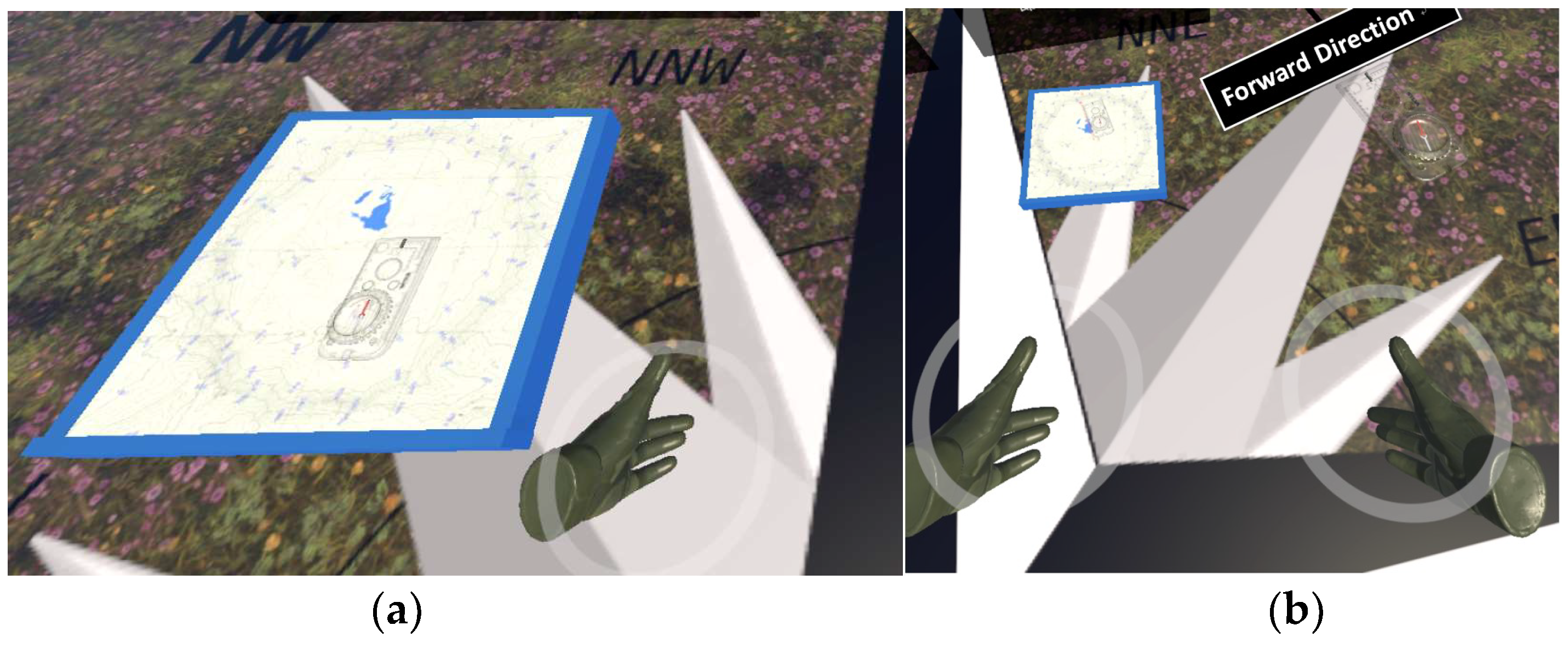

During system development, additional modules, including a drawing tool and a virtual compass, were created to support extended instructional objectives such as resection practice and magnetic declination correction. The drawing tool in

Figure 10 allows learners to sketch lines directly within the 3D environment to mark positions or record spatial reasoning processes. The virtual compass simulates real-world compass functions, including azimuth rotation, declination adjustment, and automatic magnetic needle alignment. These tools highlight the system’s scalability and potential for future applications in mountaineering education. The VR learning system integrates multiple interactive components, including map generation, orientation recognition, compass simulation, drawing, and quiz-based learning functions.

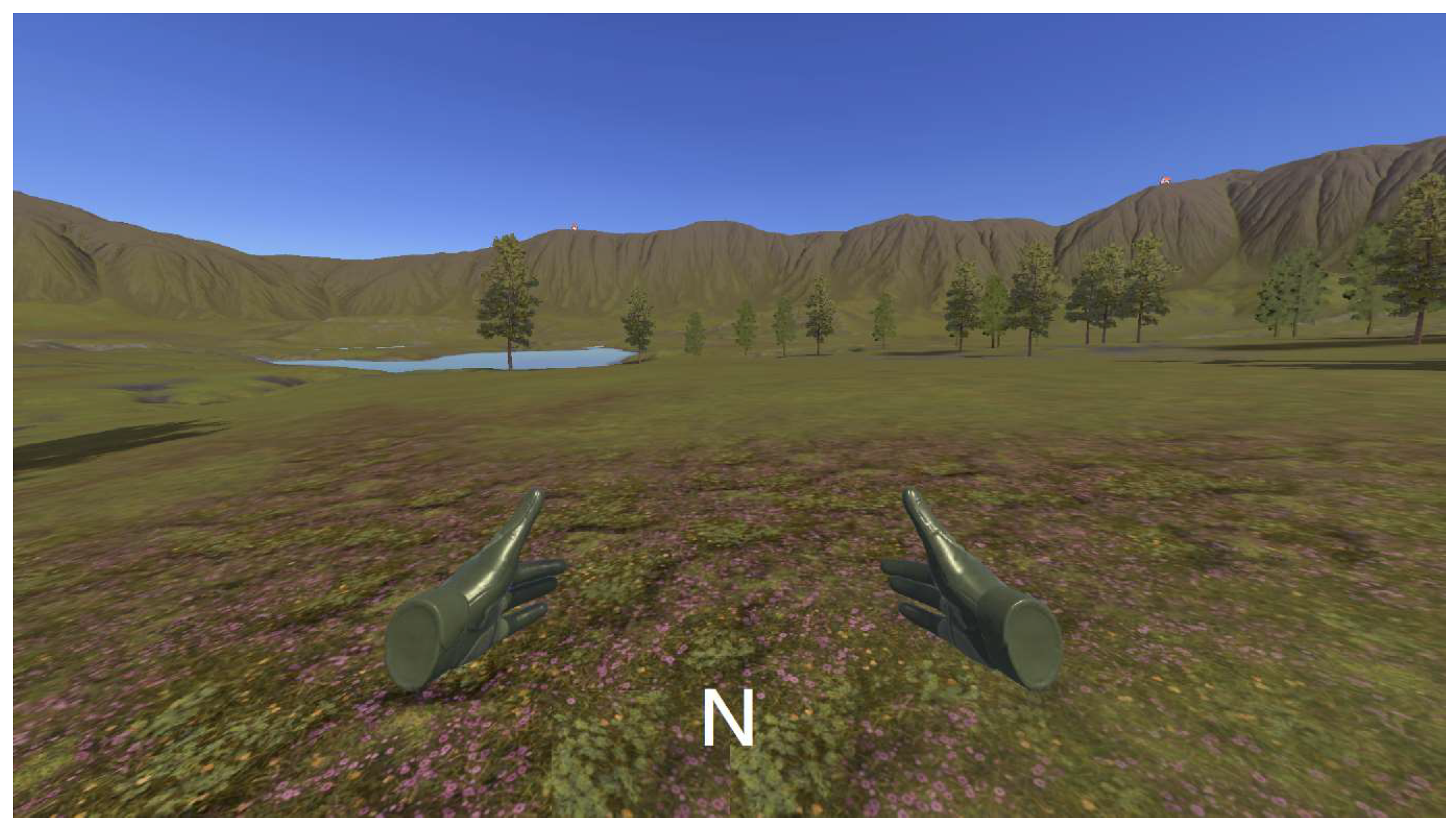

The VR instructional material is not merely an extension of digital teaching resources; it represents a digital teaching model that integrates game-based learning theory with immersive experiences, demonstrating both engagement and educational value in mountaineering education. Within the three-dimensional mountaineering scenarios, learners are required to complete clearly defined map-reading and orientation tasks. During task execution, the system provides immediate visual and directional feedback, while immersive environments simulate authentic field exploration experiences. This instructional design fosters a sense of challenge and achievement as learners progress through tasks, realizing a gamified learning experience characterized by task-driven engagement, feedback reinforcement, and immersive participation to enhance learner motivation and sustained attention during the VR training game.

The VR instructional materials developed in this study integrate task-oriented and interactive feedback mechanisms within a mountaineering education context, including compass manipulation, map drawing using a virtual pen tool, and directional recognition activities. Through active exploration, hands-on operation, and real-time feedback in a virtual environment, students experience challenge and accomplishment. The learning focus emphasizes visualized content and contextual immersion, enabling learners to concentrate on core conceptual understanding and map-reading tasks while engaging meaningfully with the VR learning environment. To ensure smooth participation, the researcher first demonstrated the basic operations of the VR system and provided a brief instruction guide before the experiment. Interaction with the VR materials was facilitated using Meta Quest 2 controllers, with the left-hand controller primarily controlling movement and positioning, and the right-hand controller managing turning, page-flipping, and task responses. This design allowed students to complete learning activities intuitively without operational interruptions. The user interface is shown in

Figure 11.

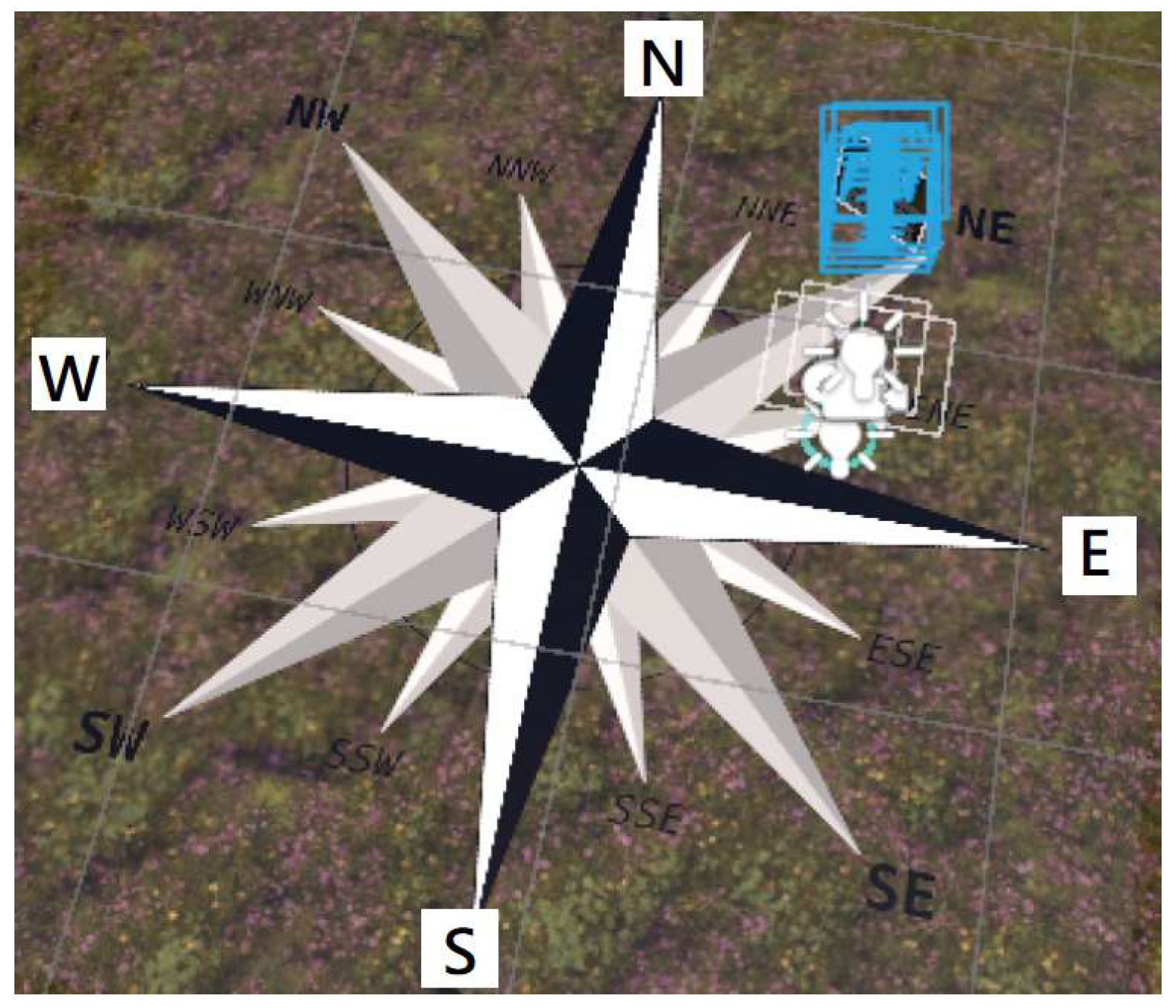

The VR instructional materials were developed in Unity (2022.3.44f1, URP) to present a fully 3D environment, enabling students to engage in immersive, interactive learning. The content was organized into four core modules:

- (1)

Orientation Recognition

This module illustrates the difference between the orientation system and magnetic north. In the virtual scene, the floor displays both directions and the corresponding labels, allowing learners to grasp positional relationships and bilingual correspondences. An illustrative diagram is provided in

Figure 12. The module’s design aligns with orientation and map-calibration principles from Ordnance Survey [

29], emphasizing the concept of “understanding space through symbols.” This approach facilitates the development of a genuine sense of direction within a three-dimensional learning environment.

- (2)

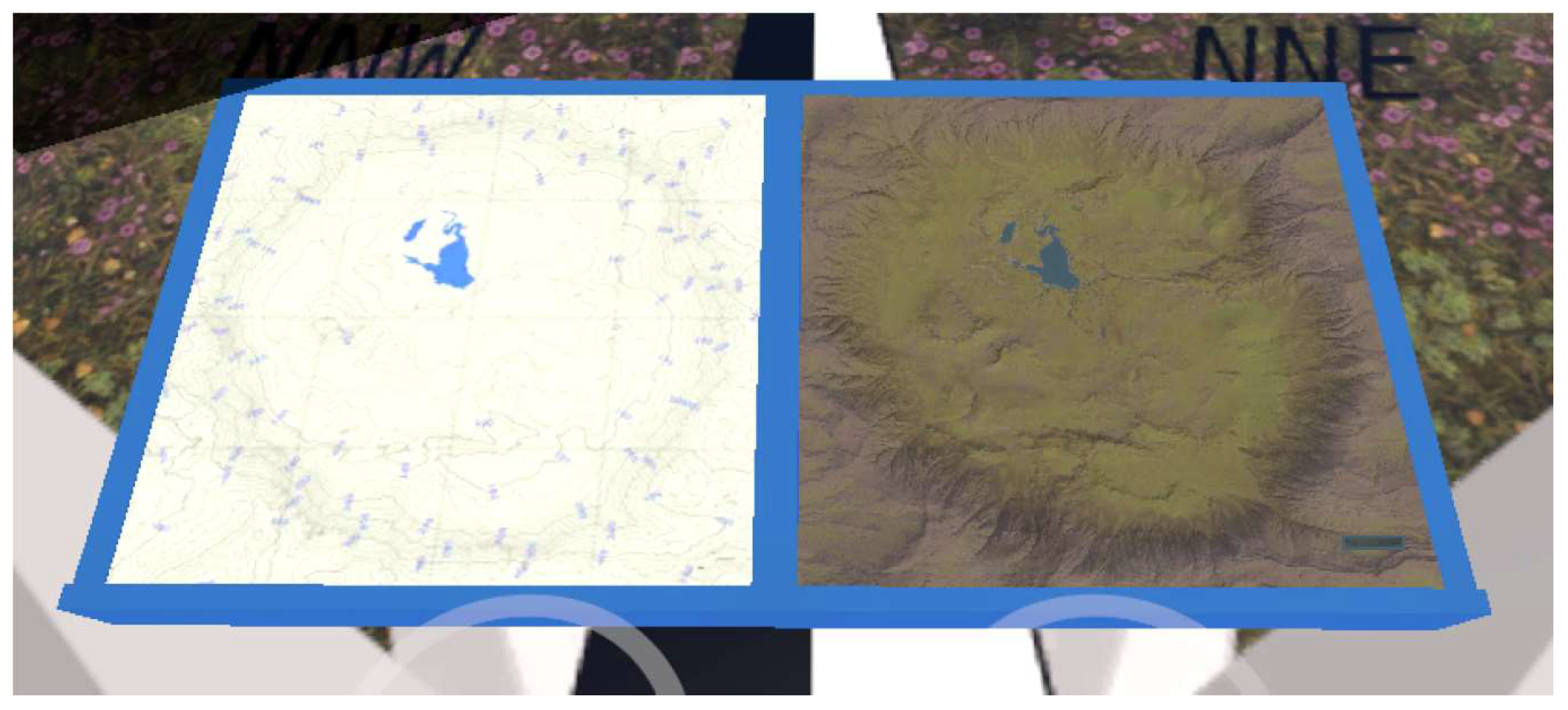

Map Elements

This module presents contour lines, elevations, grid lines, and river legends within a 3D virtual environment, allowing comparisons with aerial imagery. Drawing on the terrain and scale teaching framework from Ordnance Survey [

30], it converts traditional map elements—such as legends, contour lines, and landform symbols—into interactive 3D terrain models. This approach enables students to understand topographic variations and slope differences through enhanced spatial visualization.

The goal of this module is to help students understand the correspondence between map symbols and real-world landforms. As shown in

Figure 13, the instructional material simultaneously displays a contour map and an aerial image, allowing learners to observe differences in terrain patterns and surface features. In addition, students can use the “Real-Scene Observation” view in the VR system to explore the surrounding environment and match it with map locations, thereby strengthening their spatial correspondence and orientation skills, as shown in

Figure 14. This module, based on the 3D terrain and scale teaching framework of Ordnance Survey [

29], emphasizes visual comparison over interactive manipulation. It is designed to help students understand the relationship between map elements and the real environment, while developing foundational skills in terrain interpretation and map reading.

- (3)

Compass and Magnetic Declination

This module combines compass operation with magnetic declination correction to help students understand the difference between the geographic North Pole and magnetic north. The design includes two parts: (1) map orientation adjustment (

Figure 15a) and (2) route planning (

Figure 15b). In the first stage, students practice aligning the map with magnetic north and identifying the directional shift caused by magnetic declination. In the second stage, the module shows how to position the compass between the current and target locations, rotate the dial to align with north, and plan the route using the baseplate arrow. Students can learn magnetic declination, map alignment, and compass-based route planning for accurate navigation and spatial orientation skills.

During navigation, learners are required to keep the compass needle’s north aligned with the dial’s north to ensure directional accuracy. This process reinforces the practical relationship between compass operation and map orientation. To improve visibility and conceptual clarity, the compass is enlarged within the module. Based on the compass operation principles of the Ordnance Survey [

30], the VR module offers a dynamic simulation of magnetic declination, allowing students to observe and correct the deviation between the compass needle and true north. Through route-planning tasks, students cultivate essential skills in spatial positioning, orientation, and direction judgment.

- (4)

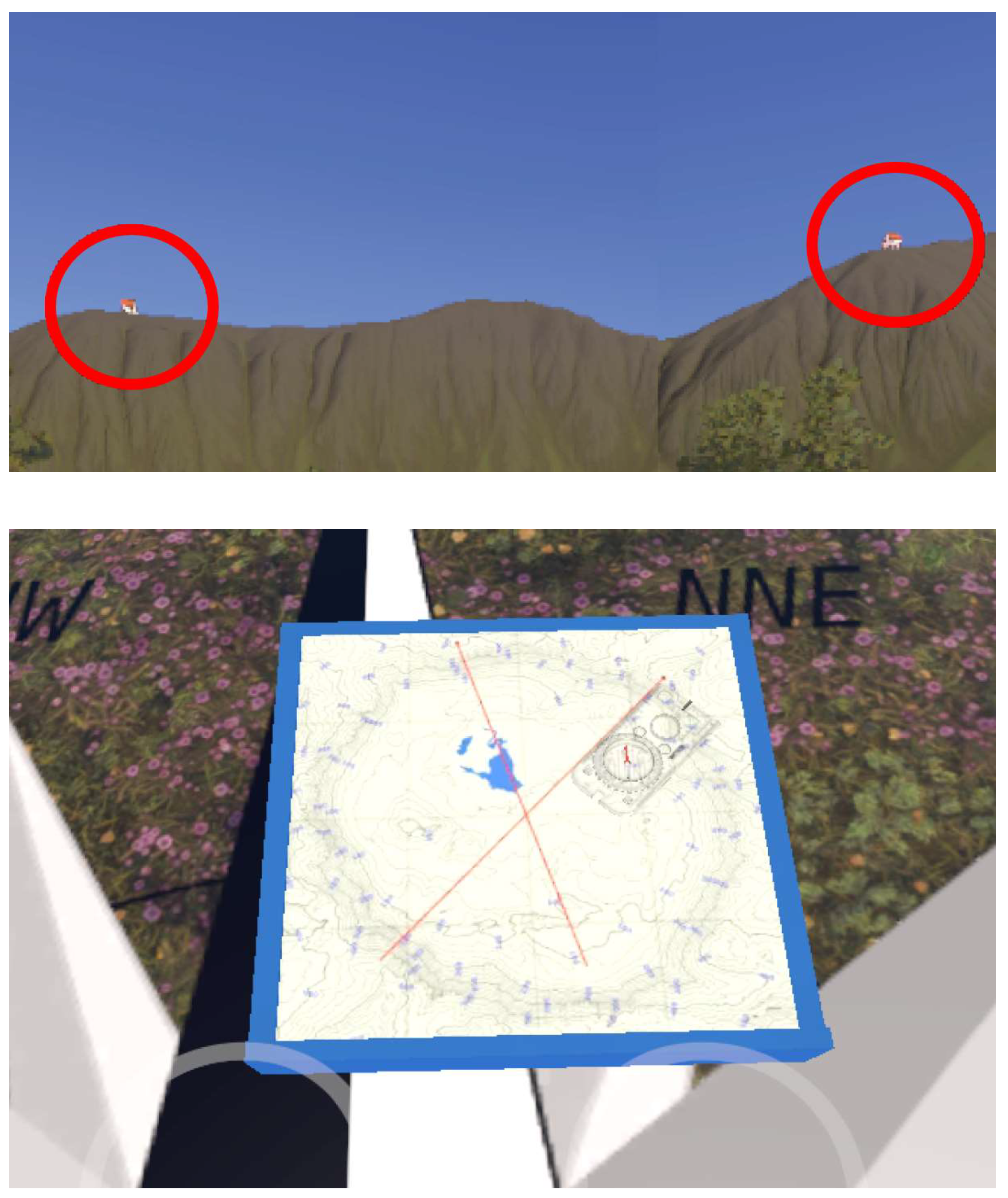

Resection Method

The Ordnance Survey [

29] identifies the resection method as an advanced map-reading skill that emphasizes the use of landmarks, bearings, and intersection observations to determine one’s current position on a map accurately. Building on this principle, the present study developed 3D instructional materials to visually illustrate the concept of resection. Although the module does not incorporate interactive manipulation, it functions as a valuable supplementary tool for teaching mountain navigation and positioning. The operational procedure of the resection method, a fundamental skill in map interpretation and spatial localization, is depicted in

Figure 16.

This module is primarily demonstration-oriented and is designed to help students understand the principles of positioning. In the 3D instructional material, students can observe the relative spatial positions of two known landmarks (reference points), which form the basis for performing intersection observations in the resection method. This design enables students to conceptually connect orientation with map correspondence in a virtual environment, facilitating a clear understanding of the fundamental principle of determining one’s position by intersecting two reference points.

Although the VR instructional material follows a “textbook-style” structure, its design incorporates the core principles of game-based learning and VR education theory. Game-based learning emphasizes task orientation, feedback mechanisms, and challenge, while VR education focuses on immersion, presence, and interactivity. This module integrates both approaches: within a 3D mountaineering scenario, learners perform explicit map-reading and orientation tasks while receiving real-time visual and directional feedback. The immersive environment simulates the experience of exploring a real field, allowing learners to encounter challenges and experience a sense of accomplishment. This design provides a gamified learning experience characterized by task-driven engagement, feedback-enhanced learning, and immersive participation, aligning with Tsai et al. [

3], who noted that gamified learning can enhance motivation and attention.

The operating procedure of the VR mountaineering education system is straightforward and designed for smooth participation. Students receive a brief demonstration of the VR system, and an instruction guide before the experiment. Interaction is facilitated via Meta Quest 2 controllers: the left-hand controller manages movement and positioning, while the right-hand controller handles turning, task responses, and page-flipping. Contextual prompts and visual cues guide learners through tasks, minimizing distractions and reducing extraneous cognitive load. Screenshots of the VR environment show clearly labeled hotspots and interactive markers that focus attention on learning content. By combining intuitive navigation, task-oriented interactions, and real-time feedback within an immersive environment, the system ensures learners remain engaged while concentrating on core concepts and map-reading tasks. This design effectively balances operational simplicity with educationally meaningful, immersive learning experiences.