Building Climate Solutions Through Trustful, Ethical, and Localized Co-Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Research Approach

2.1. Co-Development Principles and Positionality

2.2. Research Theoretical Basis

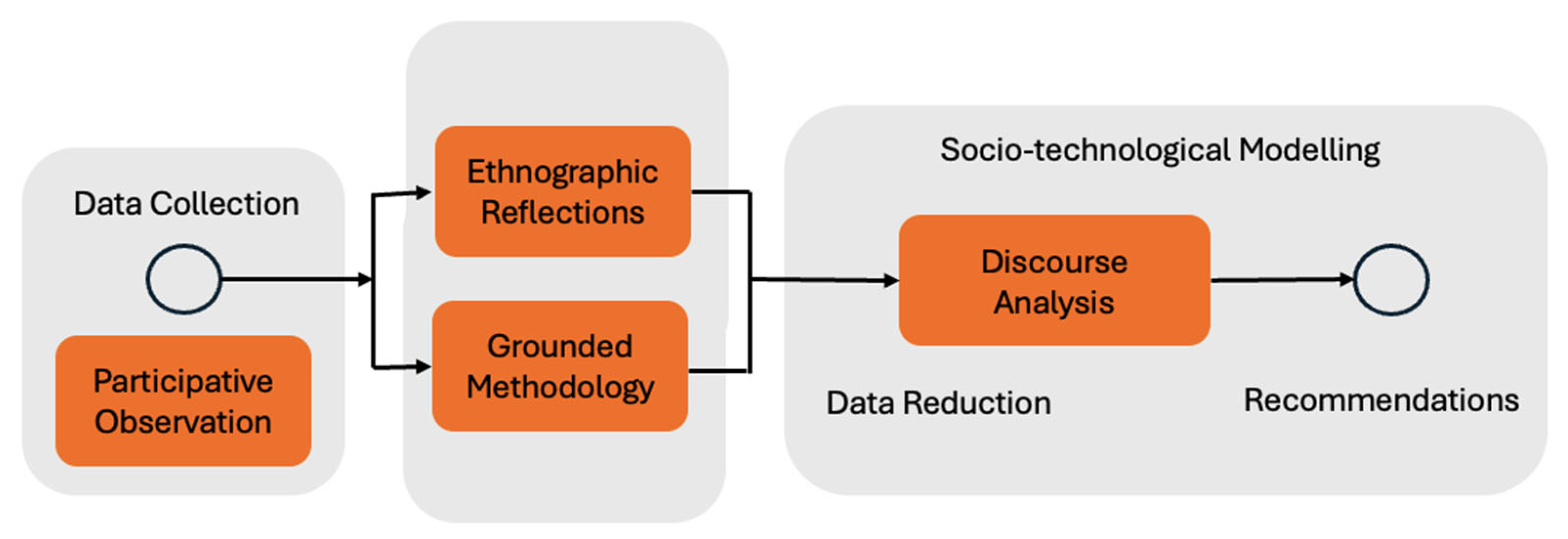

2.3. Research Methods

3. Results and Recommendations: Jamaica Case Study

3.1. Governance and Coordination

3.2. Technological Considerations: Sustainability and Financing

3.3. International Partnerships and Global-Scale Commitments

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationship and Place-Based Framework

4.2. Sociotechnical Perspective and “Degrowth”

4.3. Scientists as “Brokers”

4.4. Limitations of the Study and Impact in the LAC Region

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The lack of permanent project traceability: Existing national capacities are underutilized because international projects frequently end before local ownership can be consolidated. Given the lack of continuity and durability, trust is lost with local partners.

- (2)

- The need for bottom-to-top governance feedback loops: Community participation should be systematically incorporated into local, parish, and national planning such that local ownership and self-determination form the basis of climate-informed governance. Actors and institutions are able to better manage the interplay of single and multi-hazards and other residual risks.

- (3)

- Localization—disaster support tools and other DRR technologies co-developed, owned, and managed locally—is an ethical consideration with respect to national autonomy and sovereignty. The lack of long-term, persistent funding for internal climate analytics and modeling, forecasting infrastructure, and access to Earth observation data has become a serious disadvantage for building and developing science-informed federal policy and strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNDRR. Our World at Risk Transforming Governance for a Resilient Future, Global Assessment Report (GAR). 2022. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2022-our-world-risk-gar#container-actions (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- United Nations. UN SDG Targets and Indicators: SDG 13: Take Urgent Action to Combat Climate Change and Its Impacts. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal13#targets_and_indicators (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). REAP Anticipatory Action: The Enabling Environment Case Studies (Jamaica). Available online: https://www.early-action-reap.org/reap-anticipatory-action-enabling-environment-case-studies-jamaica (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- CCRIF. Sagicor Insurance Managers Limited, Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility. Available online: https://www.ccrif.org/about-us?language_content_entity=en (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- UNESCO Science Report: The Race Against time for Smarter Development; Executive Summary-UNESCO Digital Library. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377250 (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Massa, S.I.; Marinescu, G.S.; Fuller, G.; Bermont Díaz, L.; Lafortune, G. Sustainable Development Report for SIDS 2023: Addressing Structural Vulnerability and Financing the SDGs in Small Island Developing States, United Nations; UNOPS, Small Island Developing States. 2023. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2023/2023-sustainable-development-report-for-small-island-developing-states.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Jamaica [Country Overview]. 2024. Available online: https://data.who.int/countries/388 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Avalon-Cullen, C.; Caudill, C.M.; Newlands, N.K.; Enenkel, M. Big Data, Small Island: Earth Observations for Improving Flood and Landslide Risk Assessment in Jamaica. Geosciences 2023, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-M.; Wu, J.-X.; Gunawan, H.; Tu, R.-Q. ENSO Impacts on Jamaican Rainfall Patterns: Insights from CHIRPS High-Resolution Data for Disaster Risk Management. GeoHazards 2024, 5, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planning Institute of Jamaica. Vision 2030 Jamaica: National Development Plan; National Library of Jamaica Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; Planning Institute of Jamaica: Kingston, Jamaica, 2009; ISBN 978-976-8103-28-4. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.jm/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- UNDRR. Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation: Pathways for Sustainable Development and Policy Coherence in the Caribbean Region Through Comprehensive Risk Management; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Carby, B.; Burrell, D.; Samuels, C. Jamaica: Country Document on Disaster Risk Reduction; Office of Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Management and Jamaica Red Cross: Kingston, Jamaica, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L.; Strutzel, E. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Strategies for Qualitative Research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finidori, H.; Tuddenham, P. Pattern Literacy in Support of Systems Literacy—An approach from a Pattern Language perspective. In Proceedings of the 24th Conference on Pattern Language of Programs (PLoP), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 23–25 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, W.S. What is a number, that a man may know it, and a man, that he may know a number? Systems Community of Inquiry. Gen. Semant. Bull. 1961, 26, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo3620295.html (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Suddaby, R. From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, M.M.; Brennan, N.M. Grounded Theory: Description, Divergences and Application. Account. Financ. Gov. Rev. 2021, 27, 22173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICSU: Future Earth Research for Global Sustainability. Draft Research Framework. Available online: http://www.icsu.org/future-earth/whats-new/events/documents/draft-research-framework (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; De Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, L.C.; Talma, S.; Steeds, O.; Stefanoudis, P.; Jeremie-Muzungaile, M.-M.; de Comarmond, A. Co-development, co-production and co-dissemination of scientific research: A case study to demonstrate mutual benefits. Biol. Lett. 2021, 17, 20200699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.L.; Døhl Diouf, L.; Prescod, K. Prescod Digital inclusion in Caribbean digital transformation frameworks and initiatives: A review. Stud. Perspect. Ser.-ECLAC Subregional Hqrs. Caribb. 2022, 122, 48652. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, W.R. An Introduction to Cybernetics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society; Hachette Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Osejo-Bucheli, C. Prefiguring the Design of Freedom: An Informational Theory Approach to Socio-Political Cybernetics; Analysing the Messages in 2021 Colombian Uprisings. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2024, 37, 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradley, J.P. Participant Observation; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, R. Discourse Analysis. In Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook for Social Research; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2000; Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Yule, G. Discourse Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft. Educ. Res. 1984, 13, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I. Islandness within climate change narratives of small island developing states (SIDS). Isl. Stud. J. 2018, 13, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöck, C.; Nunn, P.D. Adaptation to Climate Change in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Literature Review of Academic Research. J. Environ. Dev. 2019, 28, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. Climate change adaptation in small island developing states: Insights and lessons from a meta-paradigmatic study. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 85, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.R. Dealing with Disaster: Hurricane Response in Fiji. 1984. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/21944 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Gane, M. Report of a Mission to Assess the Hurricane Factor for Planning Purposes in Fiji; University of Bradford, Disaster Research Unit: Bradford, UK, 1975; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Heewitt, K. Interpretations of Calamity: From the Viewpoint of Human Ecology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK; CRC Press: London, UK. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Interpretations-of-Calamity-From-the-Viewpoint-of-Human-Ecoogy/Hewitt/p/book/9780367350796 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Lewis, J. A multi-hazard history of Antigua. Disasters 1984, 8, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, C.; O’keefe, P. (Eds.) Natural Hazards in Windward Islands; University of Bradford, Disaster Research Unit: Bradford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Birthwright, A.-T.; Smith, R.-A. Put the money where the gaps are: Priority areas for climate resilience research in the Caribbean. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enenkel, M.; Kruczkiewicz, A. The Humanitarian Sector Needs Clear Job Profiles for Climate Science Translators Now More than Ever. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E1088–E1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triyanti, A.; Surtiari, G.A.K.; Lassa, J.; Rafliana, I.; Hanifa, N.R.; Muhidin, M.I.; Djalante, R. Governing systemic and cascading disaster risk in Indonesia: Where do we stand and future outlook. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 32, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES Secretariat. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Available online: https://www.ipbes.net/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Hickel, J.; Brockway, P.; Kallis, G.; Keyßer, L.; Lenzen, M.; Slameršak, A.; Steinberger, J.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. Urgent need for post-growth climate mitigation scenarios. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, V. Leaning In’ as Imperfect Allies in Community Work. Confl. Narrat. Explor. Theory Pract. 2013, 1, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, D.; Cuitzeo, M. A Cybercartographic Atlas of the Sky: Cybercartography, Interdisciplinary and Collaborative Work among the Pa Ipai Indigenous Families from Baja California, Mexico. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observational Settings (n) | Data Collection Sources | First Order Themes and Subcategories (Code Categories) |

|---|---|---|

| facilitated in-person workshops (2) | Presentations, group discussion transcripts, and reports; terms, statements, and sentiment analysis. | Governance:

|

| internal team meetings and listening sessions (10) | Team meeting notes and transcripts; terms, statements, and sentiment analysis. | |

| facilitated dialogue with national and international actors (6) | Meeting notes and transcripts; terms, statements, and sentiment analysis. | |

| conference sessions (1) | Presentation and question and answer period; terms, statements, and sentiment analysis. |

| First-Order Themes | Second-Order Themes | Key Emergent Messages |

|---|---|---|

| Governance and coordination | Geo-enabled governing bodies | Enhance integration of geospatial tools and EO data to support peer-to-peer knowledge sharing, policy training and implementation, and sustainable data partnerships for decision-makers. “…training is necessary at the community level as well as for decision-makers [at the local to federal levels], so the stakeholders can be involved and that policymakers understand the importance of financing data streams in a broad and relevant approach. EO data and local data collection is working from a foundation and building on this will produce an effective response.” “…policy adaptations need to be couched within existing frameworks, with greater inter-agency collaborations for disaster damage and loss reporting…there is a need to increase the interoperability and utility of data systems among policymakers.” |

| Bottom-to-top governance feedback loops | Establish reflexive governance systems linking community-level risk information and ownership to regional and national DRR policy. “…models [are needed] that prioritize relationship and human and technological capacity-building focus on the full social value chain, local-to-government implementation and response with practical application…” “…bottom-to-top: community use, input, and response feeding into local, regional, agency-level DRR response mechanisms, and eventually governmental policy [are needed]…” | |

| Cross-sector coordination and ownership | Promote data-sharing networks between government, academia, and community organizations for coherent DRR actions. “What they [stakeholders] can benefit from is coordination. The most critical level is the most granular level.” | |

| Technological Considerations and climate science: sustainability and financing | International commitments for in-country investments | Strengthen long-term technical partnerships for EO and climate forecasting, with rolling investments in hardware, software, and training to build local autonomy. “For low-middle income countries, it is clear that we cannot rely on government finances alone to tackle the immense issues” “A persistent challenge is that once communities have access to technologies, and this is true in academia and government, there is no consistent funding avenues for software and hardware updates…that renders them unusable over time.” |

| Financing for in-county EO climate science | Create permanent funding mechanisms for maintaining local EO data centers that inform climate adaptation and EWSs and make climate data free and accessible. “…working with the UN in coordinating disaster response in LAC…to understand how to create better response, [from this, I am] a big believer of FOSS and sharing data, regardless of where it is from. We need to convince owners of data [major international space agencies and private companies] that it is more valuable shared.” | |

| Support for in-country climate and DRR-related scientists | Provide resources for in-country science policy roles and for national experts to develop, host, and manage DSTs that integrate local knowledge and climate data. “Climate data portals, and beyond this, to go toward adaptation…and meet the accessibility gap, we now recommend moving toward open access, not just to pool resources and make linkages to existing tools methodologies, but locally developed tools.” | |

| International partnerships and global-scale commitments | Scientists as “brokers” | Establish dedicated international liaison roles that connect scientific data with global policy frameworks, ensuring actionable and coherent uptake of climate information. “Translation—it is needed for the breakdown that happens at the end of the data value chain.” “At our [academic] Center, we are working with groups to communicate science between sectors—this is sustainability in academia. We do the translation for policy, working in DRR that includes the human dimension. We are the translators who know both worlds. Resilience is the main goal, and we work under UN, Sendai, and SDGs to bring together government, society, and academia.” |

| Collaborative co-development models | Necessity for international projects to include “pre-project” listening sessions and co-design phases for equitable participation and focus on localization. “Co-production model for EWS and DRR response between academia, government, and communities for the New Urban Agenda * under climate and working with Municipalities has been the effective approach to identifying risk. We have recommended this model for Alert Systems…we recommend co-design and project planning before implementation for EWS for floods and landslides, which includes capacity building, involving women (providing childcare to help them get involved), and with Mayor’s offices to educate and train them on the tools available.” | |

| Long-term partnerships and international support mechanisms | International advocacy and commitments must extend beyond project cycles, instilling trust and ensuring continuity in data, capacity, and trust-building. “What is actionable on-the-ground for resiliency, relying on good data infrastructure, and sustainable data partnerships that meet the current significant gaps” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caudill, C.; Avalon-Cullen, C.; Archer, C.; Smith, R.-A.; Newlands, N.K.; Birthwright, A.-T.; Pulsifer, P.L.; Enenkel, M. Building Climate Solutions Through Trustful, Ethical, and Localized Co-Development. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120485

Caudill C, Avalon-Cullen C, Archer C, Smith R-A, Newlands NK, Birthwright A-T, Pulsifer PL, Enenkel M. Building Climate Solutions Through Trustful, Ethical, and Localized Co-Development. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120485

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaudill, Christy, Cheila Avalon-Cullen, Carol Archer, Rose-Anne Smith, Nathaniel K. Newlands, Anne-Teresa Birthwright, Peter L. Pulsifer, and Markus Enenkel. 2025. "Building Climate Solutions Through Trustful, Ethical, and Localized Co-Development" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120485

APA StyleCaudill, C., Avalon-Cullen, C., Archer, C., Smith, R.-A., Newlands, N. K., Birthwright, A.-T., Pulsifer, P. L., & Enenkel, M. (2025). Building Climate Solutions Through Trustful, Ethical, and Localized Co-Development. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120485